David Warsh: Eating Instagram; McKinsey and OxyContin scandal

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I was as surprised as anyone when a panel of prominent judges earlier this month chose No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, by Sara Frier, of Bloomberg News, as the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year, so I ordered it. The publisher, Simon & Shuster, was surprised, too: the book has not yet arrived. So I re-read FT staffer Hannah Murphy’s review from last April.

The book sounds absorbing enough: how Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom agreed to sell his start-up for $1 billion over a backyard barbecue at Mark Zuckerberg’s house and then watched in distress as Facebook bent the inventive photography app to purposes of its own. He finally walked away from the company he started, an enterprise that Frier called “a modern cultural phenomenon in an age of perpetual self-broadcasting” brought low by Facebook’s quest for global domination.

FT editor Roula Khalaf praised the book for tackling “two vital issues of our age: how Big Tech treats smaller rivals and how social-media companies are shaping the lives of a new generation.” In a beguiling online profile last summer, Frier explained how “everything changed” for technology reporters covering social media after the 2016 presidential election. Remembering the embrace-extend-extinguish tactics pioneered by Microsoft, antitrust authorities will also want to take a look.

There is, however, a larger issue about the contest itself. Given the temper of the times, I had thought either Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, both of Princeton University, or Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, by Rebecca Henderson, of the Harvard Business School, powerful books of unusual gravity, might capture the blue ribbon. Both specifically criticize a major McKinsey client, Purdue Pharma, and both vigorously reject the market fundamentalism that often has been imputed to the values of the secretive firm in recent decades – “shareholder value” as the only legitimate compass of corporate conduct and all that.

Granted, the prize is said by its sponsors to reward “the most compelling and enjoyable insight into modern business issues” of a given year. Previous panels have interpreted their instructions in a wide variety of ways. A McKinsey executive last year joined the judging panel. I wondered if the other members, none of them strangers to McKinsey’s lofty circles, had successfully argued to include the two critical books on the short list, before selecting a title more narrowly about “modern business issues” to avoid embarrassment to the sponsor. The awarding of literary prizes as it actually works on the inside is sometimes said to be very different from how it may look from the outside.

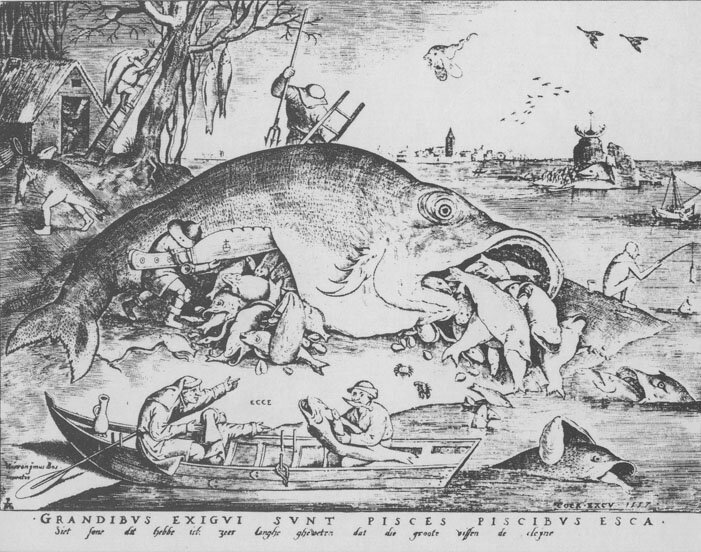

An OxyContin pill

Whatever the case, the judges could not have known about the news that broke the day before their decision was announced. The New York Times reported that documents released in a federal bankruptcy court had revealed that McKinsey & Co. was the previously unidentified-management consulting firm that has played a key role in driving sales of Purdue’s OxyContin “even as public outrage grew over widespread overdoses” that had already killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

In 2017, McKinsey partners proposed several options to “turbocharge” sales of Purdue’s addictive painkiller. One was to give distributors rebates of $14,810 for every OxyContin overdose attributed to pills they had sold. Purdue executives embraced the plan, though some expresses reservations. (Read The New York Times story: the McKinsey team’s conduct was abhorrent.) Spokesmen for CVS and Anthem, themselves two of McKinsey’s biggest clients, have denied receiving overdose rebates from Purdue, according to reporters Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe.

Moreover, after Massachusetts’s attorney general sued Purdue, Martin Elling, a senior partner in McKinsey’s North American pharmaceutical practice, wrote to another senior partner, “It probably makes sense to have a quick conversation with the risk committee to see if we should be doing anything” other than “eliminating all our documents and emails. Suspect not but as things get tougher there someone might turn to us.” Came the reply: “Thanks for the heads-up. Will do.” Elling has apparently relocated his practice from New Jersey to McKinsey’s Bangkok office, The Times’s reporters write.

Last week The Times reported that McKinsey & Co. issued an unusual apology for its role in OxyContin sales and vowed a full internal review. Sen. Josh Hawley (R.- Mo.) wrote the firm asking if documents had been destroyed. “You should not expect this to be the last time McKinsey’s work is referenced,” the firm wrote in an internal memo to employees. “While we can’t change the past we can learn from it.”

Another rethink is for the FT. The newspaper started its award in 2005, with Goldman Sachs as its co-sponsor. Tarnished by the 2008 financial crisis and the aftermath, the financial-services giant bowed out after 2013 and McKinsey took over. The enormous consulting firm is famous mainly for the anonymity on which it insists, but the Purdue Pharma scandal isn’t the first time that McKinsey has been in the news recently, especially for its engagements abroad, in Puerto Rico and Saudi Arabia. A thorough audit of its practices, reinforced by outside institutions, is overdue. In an age of mixed economies and transparency, McKinsey’s business model of mutually-contracted secrecy between the firm and the client seems outdated

Why the need for sponsorship? It would seem to be mainly a form of cooperative advertising. The cash awards to authors are lavish: £30,000 to the winner, £10,000 to each of five finalists, undisclosed sums to the judges, publicists and for advertising. That makes McKinsey’s investment a spectacular bargain, but it is something of a poisoned chalice for the FT.

The prize’s reputation as recognizing entertaining writing about important business topics is well established. Why not dispense with the money and influence? Who knows what McKinsey does and for whom? Isn’t trustworthy filtering of information the very essence of the newspaper’s business?

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.