David Warsh: The outside helpers who helped make Keynes and Friedman iconic

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946).

Keynes was a key participant at the Bretton Woods conference, which lay the foundation for much of the world’s financial system after the devastation of World War II.

The conference took place at the Mount Washington Hotel. Clouds here obscure the summits of the Presidential Range.

— Photo by Shankarnikhil88

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman traveled different paths to become the dominant policy economists of their respective times. In The Academic Scribblers, in 1971, William Breit and Roger Ransom invoked the motto of the Texas Rangers to explain Friedman’s success: “Little man whip a big man every time if the little man is right and keeps a’comin’.”

But there was more to it than that.

Both Keynes and Friedman were slow starters and late bloomers. “It was The Economic Consequences of the Peace [in 1919] that established Keynes’s claim to attention”, as biographer Robert Skidelsky wrote at the beginning of the second volume of his trilogy. In murky circumstances, the prescient warning about the hard terms imposed on Germany after World War I failed to be recognized with a Nobel Prize for Peace, as Lars Jonung has shown. Not until 1936, with the appearance of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, when he was 58, did Keynes acquire the sobriquet that Skidelsky confers on him in that second tome, “the economist as savior.”

Friedman was 50 when, in 1962, he published both Capitalism and Freedom and, with Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. He was nearly 40 when he turned to monetary theory. Within the profession he enjoyed growing success in the ‘50’s and ‘60’s. But vindication and celebrity waited until 1980, when he turned 69, as Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker battled inflation under a monetarist banner; when Friedman’s television series Free to Choose, with his economist wife, Rose. was broadcast on America’s public network; and when Ronald Reagan was elected president.

Both Keynes and Friedman freely offered advice to American presidents, which only enhanced the economists’ stature. Keynes, at arm’s length, disparaged Woodrow Wilson; encouraged Franklin Roosevelt, whom he admired, and, 15 years after his death, saw his policies adopted by John F. Kennedy. Friedman, after a 1964 unsuccessful campaign with Barry Goldwater, enjoyed considerable influence with Richard Nixon and Reagan.

So, how did the Keynesian Revolution roll out in America? There are many accounts of the process by economists, but only one by an economic historian of how America’s leading most trusted newspaper columnist first resisted, then was convinced, and facilitated the movement’s acceptance for the next 40 years. (Michael Bernstein’s A Perilous Progress: Economics and public purpose in twentieth century America (Princeton University Press, 2001) surveys the period from a somewhat different angle.)

Walter Lippmann was already America’s foremost public intellectual, a common enough species today, but then more or less one of a kind. He published A Preface to Politics a year after graduating from Harvard College, studied Thorstein Veblen and Wesley Clair Mitchell, made friends with Keynes when both attended the Versailles Peace Conference, in 1919, compared notes with U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, scientists, philosophers, central bankers, lawyers, corporate leaders and Wall Street financiers.

Lippmann began writing an influential newspaper column in the Depression year of 1931. For a taste of how different that world was from our own. I recommend a viewing of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. In Walter Lippmann: Public Economist (Harvard, 2014) the late Craufurd Goodwin, of Duke University, traces the twists and turns of Lippmann’s columns as he sorted through various explanations of the Great Depression – too much free trade, too little gold, too many monopolies, unbalanced budgets, before becoming convinced that more public public spending was the key to recovery.

After World War II, Lippmann grew close to MIT’s Paul Samuelson. He tracked the debates of emerging “neo-liberal” factions, including leaders F. A. Hayek and Friedman, but declined to join the Mont Pelerin Society. His influence as a columnist finally came to grief over his prolonged support for the War in Vietnam, and he died, at 85, in 1974.

The sources of Friedman’s support are more complicated. Within the profession he had many key allies– his Rutgers professors Arthur Burns, later chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, and Homer Jones, later research director of Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; his graduate school friends, George Stigler and Allen Wallis; his brother-in-law Aaron Director, later dean of the University of Chicago’s Law School; his co-author Anna Schwartz; and, of course, his wife, economist Rose Director Friedman, to name only his closest associates. These were among his fellow Texas Rangers.

It has been Friedman’s acolytes outside the profession who were quite different from those of Keynes. The story of the law and economic movement has been well told by Steven Teles in The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The battle for control of the law. On the financialization of markets, no one has yet topped Peter Bernstein’s Capital Ideas: The improbable origins of modern Wall Street. Friedman’s contribution to globalization is discussed in Three Days at Camp David: How a secret meeting in 1971 transformed the global economy, by Jeffrey Garten. The story of various business anti-regulation and anti-tax lobbying groups can be found in Free Enterprise: An American history, by Lawrence Glickman

It’s not that economics departments weren’t also special-interest groups, but they are special interests of a different sort, organized as competitors, which permits swift reversals within the profession itself. Whether that is the case with the legal, financial, corporate, and media industries remains to be seen. Maybe; maybe not.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: About the economics giant Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman in 2004.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The appearance of a long-awaited biography of Milton Friedman (1912-2006) has afforded me just the opportunity for which my column, Economic Principals (EP), has been looking. Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative (Farrar, Straus, 2023), by historian Jennifer Burns, of Stanford University, offers a chance to turn away from the disagreeable stream of daily news, in order to think a little about the characters who have populated the stage in the fifty years in which my column, EP has been following economics.

None was more central in that time than Friedman. We first met in his living room, in April, 1975, on a morning when he and his wife were packing for a week-long trip to Chile. We talked for an hour about the history of money. I left for my next appointment. Eighteen months later, Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Prize. I have followed his career ever since.

Ms. Burns’s book is a thoughtful and humane introduction to the life of an economist “who offered a philosophy of freedom that made a tremendous political impact on a liberty-loving country.” Standing little more the five feet tall, Friedman managed to influence policy, not just in the United States, but around the world: Europe, Russia, China, India, and much of Latin America.

How? Well, that’s the story, isn’t it?

Friedman grew up poor in Rahway, N.J. His father, an unsuccessful merchandise jobber, died when he was nine. His mother supported their four children with a series of small businesses, instilling in each child a strong work ethic. Ebullient and precocious, Milton was the youngest.

A scholarship to nearby Rutgers University put him in touch with economist Arthur Burns, then a 27-year-old economics instructor, forty years later Richard Nixon’s chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Burns took Friedman under his wing and pointed him toward the University of Chicago. He arrived in the autumn of 1932, as the Great Depression approached its nadir.

Ms. Burns unpacks and explains the doctrinal strife that shaped Friedman and their friends encountered there. They include Rose Director, a Reed College graduate from Portland, Ore., who, improbably in those hard times, had enrolled as a economics graduate student at the same time. The two became friends; they parted for a year, while Milton studied at Columbia University and Rose considered her options in Portland; then returned to Chicago, becoming a couple, as members of the “Room Seven Gang” in the campus’s new Social Science building. Other members included Rose’s older brother, Aaron, a future dean of the university’s law school; George Stigler, who would become Friedman’s best friend; and Allen Wallis, an important third musketeer.

Distinctly not a member of that gang of graduate students was Paul Samuelson, a prodigy who had enrolled as an undergraduate, at 16, nine months before Friedman arrived to begin his graduate studies. Already tagged by his professors as a future star, Samuelson was clearly brilliant, but impressed the Room Seven crowd as being somewhat toplofty.

All this, rich in details and explication, is but preface to the story. Ms. Burns follows the Friedmans to New Deal Washington, where they marry and work for a time; to New York, where Milton pursues a Ph.D. at Columbia and Rose drops out to start a family (neither undertaking turned out to be easy); to Madison, Wis., where the couple spent a difficult year while Friedman taught at the University of Wisconsin, before returning to wartime Manhattan, to be reunited with Stigler and Wallis, working at Columbia’s Statistical Research Group.

In 1945, the major phases of the story lay ahead: Friedman’s return to Chicago, to form a faculty group sufficiently cohesive to become recognized as a “second Chicago school,” significantly differentiated in important ways from the first; his embrace of monetary economics; his battles with other research groups seeking to shape the future of the profession. These included the Keynesians and organizational economists in Cambridge, Mass., the game theorists in Princeton, the mathematical social scientists at Stanford and RAND Corp., in California.

By 1957, Friedman had opened a political front. Lectures given at Wabash College in 1957 become a book, Capitalism and Freedom, in 1962. The book earned well, and the couple named “Capitaf,” their Vermont summer house for it. A Monetary History of the United States, with Anna Schwartz, all 860 unorthodox pages of it, appeared the same year. In 1964 Friedman was invited to become chief economic adviser to presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, much as Paul Samuelson had advised John F. Kennedy four years before,

The Bretton Woods Treaty, a hybrid gold standard arrangement negotiated in 1944, by Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, began to crumble; Friedman was ready with an alternative: flexible exchange rates determined in international currency markers. Distaste with the war in Vietnam exploded. Friedman proposed an all-volunteer army: that is, market-based wages for soldiers. Inflation grew out of control in the Seventies; Friedman had a ready answer, simply control the money supply. Just ahead are Margaret Thatcher, Paul Volcker, and Ronald Reagan. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement, by Milton and Rose Friedman, a 10-part public television series, appears in 1980, becoming an international best-seller, followed by a book.

But that is getting ahead of the story here. Ms. Burns relates all this and its surprising conclusion with grace and attention to detail. No wonder it took nine years to write! In the end it offers a seamless account. But in that very seamlessness lies a rub.

Ms. Burns is a cultural historian, concerned with rise of the American right, which in the 1950s seemed to come out of nowhere: The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich Hayek (Chicago, 1944); Sen Joe McCarthy; the John Birch Society; God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (Regnery, 1951), by William F. Buckley Jr.; The Conscience of a Conservative (Victor, 1960), by Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, and the subsequent Goldwater presidential candidacy, and all that. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford, 2009) was her previous book. She knows Friedman’s influence on economics was great – too great to cover adequately in her book. Even the subtitle raises more questions than the book itself can answer.

Therefore, as I continue to peruse Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, I intend to write over the next nine weeks about nine different books, each of which covers some aspect of Friedman’s story from a different angle. Trust me, the story is worth it: you’ll see. Meanwhile, if you get tired of reviewing the last seventy-five years, there is always the dismal news in the newspapers today.

. xxx

In a rush last week to get something into pixels about the American Economic Association meetings in San Antonio, I committed an embarrassing error.

Michael Greenstone, of the University of Chicago, delivered the AEA Distinguished Lecture, not Emmanuel Saez. You can find “The Economics of the Global Climate Challenge” here. If you care about climate warming, or simply want a glimpse of where the economics profession is headed, Mr. Greenstone’s lecture is well worth the hour it takes to watch.

That the Princeton Ph.D. and former MIT professor is today the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor and former director of the Becker-Friedman Institute adds authority to his message.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Beats thinking

“Muscle Memory” (monoprint drypoint construction with violin and mirror), by Massachusetts artist Debra Olin, at Brickbottom Artists Association’s (Somerville, Mass.) members show, through Nov. 19.

David Warsh: Claudia Goldin's Nobel Prize was for many reasons

Claudia Goldin

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The award of any Nobel Prize is an invitation to go prowling through the past. In the case of Claudia Goldin, of Harvard University, born in 1946, the history on offer is that of an entire generation – not just one crucial generation, in fact, but three. Hers is the first fifty-year career by a woman in major league economic research since that of Joan Robinson (1903-1983). Perhaps not since John Nash shared the prize, in 1994, has a single life in economics been so intricately connected to the context of its times as that of Goldin.

Calling Sylvia Nasar, author of the Nash biography, A Beautiful Mind!

For one thing, Goldin is a third-generation Nobel laureate. She wrote her dissertation under the direction of economic historian Robert Fogel, of the University of Chicago, who wrote his under Simon Kuznets, of Johns Hopkins University (in Goldin’s case, with significant influence by labor theorist Gary Becker as well.)

For another, she lived the full University of Chicago experience, before escaping to a place of her own. Some years ago, she told Douglas Clement, of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, that her Cornell undergraduate mentor, Fred Kahn (who later became Jimmy Carter’s economic adviser), discouraged her from going.

“When I went to Cornell, the room that I entered was filled with paintings and good food. But Chicago was a castle, a completely different universe. I walked in and realized, once again, that I knew nothing. Now I knew absolutely nothing.… [She had gone to study industrial organization with George Stigler.] And then Gary [Becker] arrived, and once again I realized that the world of economics was much larger than I had thought. Gary was doing brilliant work on many different issues that I would call the economics of social forces. And then, to make things even better, I met Bob Fogel … [who] mesmerized me with economic history, and that combined my liberal arts junkie taste with my more rigorous math sensibilities.”

There followed twenty years of professional turbulence. After top-tier Chicago, she spent two years at third-tier Wisconsin, followed by six years in a top-ranked Princeton department, before settling down to tenure at the second-tier University of Pennsylvania. These were years when the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession was organizing, decades in which women began going to law and medical schools in significant numbers, but advances came much more slowly in economics.

Goldin’s major phase began in 1990, when she was appointed Harvard’s first tenured female professor of economics. She published Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women the same year, and was named director of the program on the Development of the American Economy of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Since then, nobody has written more thoughtfully and imaginatively about the myriad economic complexities of female gender in and out of the labor force, culminating in Career & Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021).

There is, as well, a love story. Goldin married her fellow Harvard economist Lawrence Katz, a labor economist. Over the course of several years, the pair produced an important and heavily documented study of the rise of the high-school movement in the United States in the late 19th Century, designed to prepare workers for an emerging industrial economy. The Race between Education and Technology Society (Harvard Belknap, 2009) is routinely cited among their most enduring contributions. In most respects, Katz is not a trailing spouse; earlier this month he was elected president of the American Economic Association.

Peter Fredriksson, of the University of Uppsala, a member of the committee that recommended the prize to Goldin, described last week several years of hard work as committee members untangling one contribution from the many others that warranted recognition. In the end, he said, they settled on the combination of economic history and labor economics that produced a U-shaped portrait of the changing trade-off between careers and family. Per Kussell, professor at Stockholm University and secretary to of the committee, emphasized “The prize is not the person, it’s for the work.”

Yet in this case, the person is equally interesting. I don’t know any of the details. But I am fairly certain Goldin’s is an unusually good story. Her prize was overdetermined, in that it was awarded for many overlapping reasons. For more than a decade it was understood that it eventually would be given. Better sooner than later. It makes a fitting climax to the story of one generation and the rising of the of the next.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Of economics ideas and the power of big business to shape policies

Theater lobby card for the American short comedy film Big Business (1924)

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, by Nami Oreskes and Erik Conway, was a hard-hitting history in 2010 that catapulted its authors to fame – Oreskes all the way to Harvard University; Conway remained at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech.

Their new book – The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market (Bloomsbury, 2023) – the authors describe as a prequel. In identifying the doubters, it exhibits the same strengths as before. It displays greater weaknesses in establishing the various truths of the matter. It is, however, a page-turner, a powerful narrative, especially if you are already feeling a little paranoid and looking for a good long summer read.

It’s all true, at least as far as it goes. Those three powerful intellects – Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises – started with unpopular arguments and won big. From the National Electric Light Association and the Liberty League in the Twenties and Thirties, the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Chamber of Commerce in the Fifties and Sixties, to the Federalist Society and the Club for Growth of today, business interests have been spending money and working behind the scenes to boost enthusiasm for markets and to undermine faith in government initiative.

To tell their gripping story of ideas and money, Oreskes and Conway rely on much work done before. Pioneers in this literature include Johan Van Overveldt (The Chicago School: How the University of Chicago Assembled the Thinkers who Revolutionized Economics and Business, 2007); Steven Teles (The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law); 2008); Kim Phillips-Fein, (Invisible Hands: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2009); Jennifer Burns (Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, 2009); Phillip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe (The Road to Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, 2009); Daniel Rodgers (Age of Fracture, 2011); Nicholas Wapshott (Keynes Hayek: The Clash that Defined Modern Economics, 2011); Angus Burgin (The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression, 2012); Daniel Stedman Jones (Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2012); Robert Van Horn, Phillip Mirowski and Thomas Stapleford, (Building Chicago Economics: New Perspectives on the History of America’s Most Powerful Economics Program, 2011); Avner Offer, and Gabriel Söderberg (The Nobel Factor: The Prize in Economics, Social Democracy, and the Market Turn, 2016); Lawrence Glickman (Free Enterprise: An American History, 2019); Binyamin Appelbaum (The Economists’ Hour: False Prophets, Free Markets, and the Fracture of Society) 2019); Jennifer Delton (The Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American Capitalism, 2020); and Kurt Andersen (Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America a Recent History, 2020). Biographies of Robert Bartley and Roger Ailes remain to be written.

So about those weaknesses? They boil down to this: In The Big Myth you seldom get the other side of the story. Take a fundamental example. Oreskes and Conway assert that “the claim that America was founded on three basic interdependent principles: representative democracy, political freedom, and free enterprise,” cooked up in the Thirties by the National Association of Manufactures for an advertising campaign. This so-called called “Tripod of Freedom” was “fabricated,” Oreskes and Conway maintain; the words free enterprise appear nowhere in the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, they declare. That stipulation amounts to a curious “blind spot,” Harvard historian Luke Menand observed in a lengthy review in The New Yorker. There are mentions of property, though, writes Menand, “and almost every challenge to government interference in the economy rests on the concept of property.” See Adam Smith’s America: How a Scottish Philosopher Became an Icon of American Capitalism (Princeton, 2022), by Glory Liu, for elaboration.

Similarly, the previous Big Myth with which the market fundamentalists and the business allies were contending received little attention. As the industrial revolution gathered pace in the late 19th Century, progressives in the United States preached a gospel of government regulation. Germany’s success in nearly winning World War I received widespread attention. Britain emerged from World War II with a much more socialized economy than before. And in the U.S., government planning was espoused by such intellectuals as James Burnham and Karl Mannheim as the wave of the future.

Finally, The Big Myth largely ignores the experiences of ordinary Americans in the years that it covers. For all the fury that Big Coal mounted against the Tennessee Valley Authority, its dams were built, nevertheless. There is only a single fleeting mention of George Orwell, though his novels Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949) probably influenced far more people than Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. Paul Samuelson’s textbook explanation of the workings of “the modern mixed economy” dominated Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom tract for forty years and probably still does.

Yet there can be no doubt that there was a disjunction. Oreskes and Conway mention that in the ‘70’s conservative historian George Nash considered that nothing that could be described as a conservative movement in the mid-’40s, that libertarians were a “forlorn minority.” President Harry Truman was reelected in 1948, and Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate Republican, served for eight years after him. Suddenly. in 1964, Republicans nominated libertarian Barry Goldwater. Then came Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

What happened? America’s Vietnam War, for one thing. Globalization for another. Massive migrations occurred in the US, Blacks and Hispanics to the North, businesses to the West and the low-cost South. Civil rights of all sorts revolutions unfolded, at all points of the compass. The composition of Congress and the Supreme Court changed all the while.

In Merchants of Doubt, Oreskes and Conway were on sound ground when making claims about tobacco, acid rain, DDT, the hole in the atmosphere’s ozone layer and greenhouse-gas emissions. These were matters of science, an enterprise devoted to the pursuit of questions in which universal agreement among experts can reasonably hope to be obtained. It was sensible to challenge the reasoning of skeptics in these matters, and to probe the outsized backing they received from those with vested interests. The interpretation of a hundred years of American politics is not science; much of it is not even a topic for proper historians yet. Agreement is reached, if at all, through elections, and elections take time.

Again, take a small matter, the interpretation of “the Reagan Revolution.” Jimmy Carter started it, Oreskes and Conway maintain; Bill Clinton finished it via the “marketization” of the Internet, and most persons have suffered as a result. It is equally common to hear it proclaimed that Reagan presided over an agreement to repair the Social Security system for the next fifty years, ended the Cold War on peaceful terms, and, by accelerating industrial deregulation, ensured on American dominance in a new era of globalization.

In arguments of this sort, EP prefers Spencer Weart’s The Discovery of Global Warming to Merchants of Doubt and Jacob Weisberg In Defense of Government: The Fall and Rise of Public Trust to The Big Myth. But I share Oreskes’ s and Conway’s concerns while searching for opportunities to build more consensus. A century after today’s market fundamentalists began their long argument with Progressive Era enthusiasts for government planning, sunlight remains the best disinfectant.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: AI firms and news publishers are dickering over revenue sharing

Baker Library at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College’s Kiewit Computation Center, cutting edge when it was built, in 1966, and torn down as outdated, in 2018

From Cantor’s Paradise:

“The Dartmouth (College) Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was a summer workshop widely considered to be the founding moment of artificial intelligence as a field of research. Held for eight weeks in Hanover, New Hampshire in 1956 the conference gathered 20 of the brightest minds in computer- and cognitive science for a workshop dedicated to the conjecture:

"..that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves. We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer."

-- A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (McCarthy et al., 1955)

Somerville, Mass.

Why the speed with which artificial intelligence technologies have been sprung on the world? The answer may have something to do with the model that AI companies have in mind for the most potentially lucrative among their new businesses. Once again it seems to have to do mostly with advertising.

As a result, the newspaper business, broadly defined to include data-base/software businesses such Bloomberg, Reuters and Adobe, is taking stock of itself and its prospects as never before. Readers are learning about the capabilities and limitations of generative artificial intelligence engines, which can produce on demand Wiki-like articles containing detailed but not necessarily dependable information. In the bargain, we may even learn something important about the systems of industrial standards that govern much of our lives.

Those implications emerged from a Financial Times story other week that Google, Microsoft, Adobe and several other AI developers have been meeting with news company executives in recent months to discuss copyright issues involving their AI products, such as search engines, chatbots and image generators, according to several people familiar with the talks.

FT sources said that publishers including News Corp, Axel Springer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and The Guardian have each been in discussions with at least one major tech company. Negotiations remain in their early stages, those involved in them told the FT. Details remain hazy: annual subscriptions ranging from $5 million to $20 million have been discussed, one publisher said.

This much is already clear: Media companies are seeking to avoid compounding the mistakes that allowed Google and Facebook to take over from print, broadcast and cable concerns the lion’s share of the advertising business, in a wave of disruption that began around the start of the 21st Century.

A major problem involves avoiding further concentration among media goliaths. At stake is the privilege of decentralized newspapers, competing among themselves, to remain arbiters of democracies’ provisional truth, the best that can be arrived at quickly, day after day.

Mathais Döpfner. whose Berlin-based media company owns the German tabloid Bild and the broadsheet Die Welt, told FT reporters that an annual agreement for unlimited use of a media company’s content would be a “second best option,” because small regional or local news outlets would find it harder to benefit under such terms. “We need an industry-wide solution,” Döpfner said. “We have to work together on this.”

The background against which such discussions take place is copyright law. Obscured is the role frequently played by privately negotiated industry standards.

Behind the scenes talks will continue. But the changing nature of advertising-based search is a breaking story. Newspapers remain free to take their case to the public, in hopes of government intervention of unspecified sorts.

The adage applies about lessons learned from experience: fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

#David Warsh

#artificial intelligence

David Warsh: It may be too late but here’s a suggestion on saving print newspapers

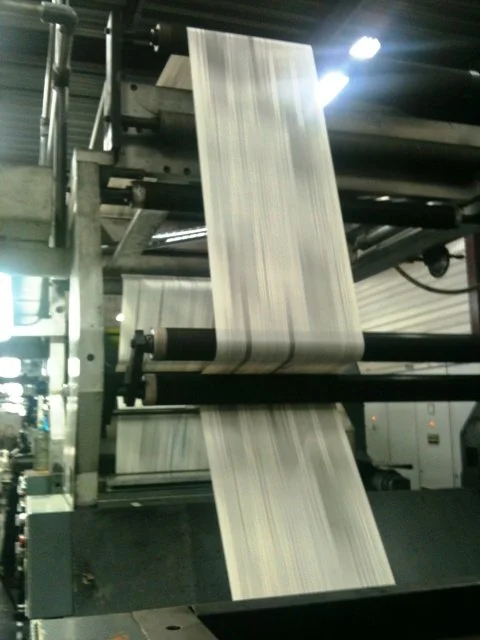

Newspapers rolling off the press

— Photo by Knowtex

1896 ad for The Boston Globe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It may have been pure coincidence that strains on American democracy increased dramatically in the three decades after the nation’s newspaper industry came face to face with digital revolution. Then again, the disorder of the former may have something to do with the latter.

Since 2001, the last good year, daily circulation of major metropolitan newspapers has been plummeting. An edifying survey last year found that The Wall Street Journal, at the top of the field, delivered more print copies daily (697,493) than its three next three competitors combined: The New York Times (329,781), USA Today (149,233) and The Washington Post (149,040).

All but one of the top 25 newspapers reported declining print circulation year-over-year. The Villages Daily Sun, founded in 1997 in central Florida, not far north of Orlando, was up 3 percent, at 49,183, ahead of the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Is there still a market for print newspapers? Maybe, maybe not. There is probably only one good way to answer the question. I’d like to suggest a simple experiment: compete on price.

The New York Times Company bought The Boston Globe 30 years ago this week for $1.13 billion, in the last days of the golden age of print journalism. The Times ousted the Globe’s fifth-generation family management in 1999, installed a new editor in 2001, and, for 10 years, rode with the rest of the industry over the digital waterfall.

The Globe, whose 2000 circulation had been roughly 530,000 daily and 810,000 Sunday, broke one great story on the way down. Its coverage of the systemic coverup of clerical sexual abuse of minors in the Roman Catholic Church beginning in 2002 has reverberated around the world. The story produced one more great newspaper movie as well – perhaps the last — Spotlight. Otherwise the New York Times Co. mismanaged the property at every opportunity, threatening at one point to simply close it down. It finally sold its New England media holdings in 2013 to commodities trader and Boston Red Sox owner John W. Henry for $70 million.

Since then, the paper has stabilized, editorially, at least, under the direction of Linda Pizzuti Henry, a Boston native with a background in real estate who married Henry in 2009. Veteran editor Brian McGrory served for a decade before returning to column writing this year. Nancy C. Barnes was hired from National Public Radio to replace him; editorial page editor James Dao arrived after 20 years at the Times. A sustained advertising campaign and new delivery trucks gave the impression the Globe was in Boston to stay.

Henry himself showed some publishing flair, starting and selling a digital Web site, Crux, with the idea of “taking the Catholic pulse,” then establishing Stat, a conspicuous digital site that covers the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. Henry’s sports properties – the Red Sox, Britain’s Liverpool Football Club, a controlling interest in the National Hockey League’s Pittsburgh Penguins, and a 40 percent interest in a NASCAR stock car racing team, are beyond my ken.

There is, however, one continuing problem. The privately owned Globe is thought to be borderline profitable, if at all. It seems to have followed the Times Co. strategy of premium pricing. Seven-day home delivery of The Times now costs $1305 a year. Doing without its Saturday and overblown Sunday editions brings the price down to $896 for five days a week. The year-round seven days a week home delivery price for The Globe is posted in the paper as $1,612, though few subscribers seem to pay more than $1200 a year, to judge from a casual survey.

In contrast, six-day home delivery of WSJ costs $720 a year. The American edition of the Financial Times, in some ways a superior paper, costs $560 six days a week, at least in Boston. It is hard to find information about home-delivery prices for The Washington Post, now owned by Amazon magnate Jeff Bezos. But $170 buys out-of-town readers a year’s worth of a highly readable daily edition.

So why doesn’t The Globe take a deep breath and cut home-delivery prices to an annual rate of $600 or so, to bring its seven-day value proposition in line with those of the six-day WSJ and the FT? The Globe trades heavily on legacy access to wire services of both The Times and The Post; it is not clear how this would fit into such a bargain with readers. Long-time advertising campaigns would be required to make the strategy work.

That would be taking a leaf from The Times’s long-ago playbook. In 1898, facing falling ad revenues amid malicious rumors that it was inflating its circulation figures, publisher Adolph Ochs, who had bought the daily less than three years before, cut without warning its price from two cents to a penny, to the astonishment of his principal New York competitors on quality, The Herald and The Tribune. He quickly gained in volume what he gave up for the moment in revenue, raised the price a year later, and never looked back. The move has been hailed ever since as “a stroke of genius.”

Would it work today? It might. If it did, it would constitute a proof of concept, an example for all those other formerly great metropolitan newspapers to consider in hopes of creating a standard for two-tier home-delivery pricing: one price for the national dailies; a second, slightly lower price for the less-ambitious home-town sheet.

It might force The Times to cut back on its Tiffany pricing strategy, to take advantage of once-again growing home-delivery networks, and get print circulation increasing again, after two decades of gloomy decline.

Even digital publisher of financial information Michael Bloomberg might be persuaded to put his first-rate news organization to work publishing a thin national newspaper, on the model of the FT. Print newspapers have a problem with pricing subscriptions to their print daily papers. It is time for industry standards committees to begin considering the prospects.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

“Newspaper readers, 1840,’’ by Josef Danhauser

A carnival’s ‘childlike carefreeness’

“Traveling Circus’’ (oil on canvas), by Alexandra Rozenman, in Brickbottom Artists Association, Somerville, Mass., June 17-29

The gallery says:

‘‘There is a certain special kind of joy that takes place when the carnival comes to town. Nostalgia, excitement, and a childlike carefreeness that can be unshakeable for guests of all ages. The carnival can seem like a very intricate web of logistics but with the proper event planning team, you can put together a five-start carnival just about anywhere. Even your very own backyard.’’

This 1945 Rodgers & Hammerstein Broadway musical is set on the Maine Coast. Rodgers said later it was his favorite of all his shows.

David Warsh: Defense of and attack on government debt

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Weary of reading play-by-play stories about the Treasury Department’s efforts to manage in light of the hold-up by right-wing Republicans over reaching the federal debt ceiling – impoundment decisions, discharge petitions and various accounting maneuvers – I took down my copy of Barry Eichengreen’s In Defense of Public Debt (Oxford, 2021) to remind me of what, at bottom, the fracas is all about.

Eichengreen, an economic historian at the University of California at Berkeley, is still not yet a household word in homes where economics is dinner-table conversation, though earlier this month he was named (with four others) a distinguished fellow of the American Economic Association, the profession’s highest honor.

He was recognized chiefly for having written Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression 1919-1939 (Oxford, 1992), which has become the standard account of how the Great Depression was so globally damaging – the role that the gold standard played in transmitting around the world its origins in the United States.

But it was sheer good citizenship that led Eichengreen and three other experts – Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves and Kris James Mitchener – to write what their publisher describes as “a dive into the origins, management, and uses and misuses of sovereign debt through the ages.” Their Defense turns out. too, to be useful in looking ahead to what is said to be a looming crisis of global debt. .

Their book begins with another dramatic moment of American civic life: Sen, Rand Paul (R.-Ky.) inveighing in December 2020, against government borrowing earlier that year on news of the outbreak of the global Covid pandemic:

How bad is our fiscal situation? Well, the federal government brought in $3.3 trillion in revenue last year and spent $6.6 trillion, for a record-setting $3.3 trillion deficit. If you are looking for more Covid bailout money, we don’t have any. The coffers are bare. We have no rainy day fund. We have no savings account. Congress has spent all of the money.

Paul’s alarm was based on a fundamental insight, Eichengreen and his co-authors write, namely that governments are responsible for their nations’ finances. If they borrow frivolously, or excessively, bad consequences usually follow, On the other hand, if national governments fail to borrow in a genuine emergency – to fight a war deemed necessary; to staunch a financial panic; to facilitate a domestic political pivot – even worse damages might ensue. The sword is two-sided: Public debt has its legitimate uses, after all. .

A market for sovereign debt has existed for millennia. Kings and war-lords borrowed, most often to wage war. They paid exorbitant interest rates because they often defaulted. It was only in the 17th Century, as modern nations began to emerge, that viable institutions of public debt were established, first in England and the Netherlands.

Constitutional governments, with legislatures and parliaments, made it possible for would-be lenders to participate in decisions to borrow, to engineer realistic hopes of getting their money back, as they turned in the coupons they clipped from their government bonds in exchange for semi-annual payments of interest. Advice and consent became part of the game.

From the beginning, there was ambivalence. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith himself warned that it would be all to easy for nations to borrow profligately against the promise of future tax revenues, Eichengreen noted. Smith made an exception mainly for war. As it turned out, the stabilization of British government debt markets organized by Robert Walpole after the disastrous South Sea Bubble, which popped in 1720, became the original military industrial complex. Many scholars credit superior borrowing capacity for Britain’s eventual victory in the Napoleonic Wars.

Government borrowing expanded to other purposes in the 19th Century, Eichengreen writes, especially for investments in canals and railroads intended to foster geographic integration and growth. Central banks learned how to halt financial panics by serving as lenders of last resort.

In the 20th Century, he says, the emphasis shifted again, this time to social services and transfer payments. Government borrowing financed the creation of the modern welfare state. And, of course, governments continue to shoulder the responsibility to maintain overall financial stability.

Today, the argument is between “conservative” radicals who hope to disassemble the welfare state, and radical “progressives,” who seek to expand it with little concern for the dangers of borrowing too much. In the center are a large corps of sensible citizens, such as Eichengreen, who seek to harness the existing system of taxing and borrowing and spending to let it work in a sensible and less expensive manner.

The market for government debt has survived, Eichengreen notes, “indeed thrived, for the better part of five hundred years.” It is an indispensable part of the world’s fiscal plumbing. Tinkering with it is fine; holding it hostage makes no sense at all. In Defense of Public Debt is an excellent primer on all these issues. I haven’t done it justice, but I started too late, and have run out of time.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Those missed Nobel Prizes

Front side of a Nobel Prize.

Photo by Jonathunder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.,

When Dale Jorgenson died last summer, of long Covid, at 89, sighs were heard throughout the worldwide community of measurement economists. Had the Swedish authorities at long last been preparing to recognize the founder of modern growth accounting? Did the Reaper rob the Harvard University econometrician of his Nobel Prize?

Probably not. It seemed that, barring exigency, the Nobel panel had decided long ago to pass him by. It was left to Martin Baily, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, to tell The Wall Street Journal’s James Hagerty that Jorgenson “should have been awarded a Nobel Prize….” The same has been said of many other often-nominated candidates, including, for example, American novelists Philip Roth, of Connecticut, and John Updike, of Massachusetts.

On a memorial service yesterday, in Harvard’s Memorial Church, it almost didn’t matter. The talk was of families, friendships, skits (including one in which Jorgenson was portrayed as Star Trek’s Mr. Spock): the old days, when the Harvard Economics Department’s youngers members and their students were housed in a converted hotel across the street from IBM’s mainframe computers. Colleagues Barbara Fraumeni, Mun Sing Ho and Benjamin Friedman spoke; so did Jorgenson’s former student Lawrence Summers. Another former student, Ben Bernanke, whose undergraduate thesis Jorgenson supervised, missed the service, on his way to Stockholm to share a Nobel Prize; the two had remained in life-long touch.

Still, the question remained, why not Jorgenson?

Certainly it was not for lack of dominating achievements in his chosen field, of growth and productivity measurement. Born in 1933, Jorgenson grew up in Montana, attended Reed College, in Portland, Ore., and, in 1959, received his PhD from Harvard, where future Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief had supervised his thesis. He took a job at the University of California at Berkeley, where he taught the graduate theory course.

In 1963 Jorgenson published “Capital Theory and Investment Behavior.” When a committee selected the 20 most important papers that the American Economic Review had published in its centenary celebration, Jorgenson’s article was among them – the only contribution to have appeared in print immediately, without the customary wait for referee reports. The 13-page paper was revolutionary in two ways, according to Robert Hall, of Stanford University:

It combined finance with the theory of the firm to generate a coherent theory of the firm’s purchase of capital inputs, an area of considerable confusion prior to Jorgenson’s work. And it also laid out a paradigm for empirical research that called for serious economic theory to provide the backbone of the measurement approach. Jorgenson showed how to integrate data and theory.

As Berkeley boiled over with student protests in the 1960s, its best economists began to leave for Harvard: first Richard Caves and Henry Rosovsky, then David Landes, and, in 1969, Jorgenson. They were part of Harvard’s response to having been eclipsed in economics beginning 25 years earlier, by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Kenneth Arrow, Zvi Griliches, Martin Feldstein, and John Meyer were recruited as well, from Stanford, Chicago, Oxford and Yale respectively.

In 1971, Jorgenson won the bi-annual John Bates Clark Medal, awarded for contributions to economics before the recipients turned 40, as had Griliches, in 1965, and Arrow, in 1957. Feldstein would be similarly recognized in 1977.

Jorgenson’s contributions continued at a steady pace for more than 50 years at Harvard. The most significant of these was a successful campaign to produce industry-by-industry input-output tables with which to elucidate national income accounts prepared in the 1930s. Aggregate growth accounting depended fundamentally on the concept of value-added, according to John Fernald, author of a comprehensive account of Jorgenson’s career.

But Evsey Domar had written as early as 1961 that value-added accounting was only “shoes lacking leather and made without power.” To identify the changes occurring in productivity a complete set of input-output tables would be required, disaggregated by industry, linking Leonief/Jorgenson accounting with the old national income accounts designed by Nobel laureate Simon Kuznets. .

Working with Ernst Berndt, Frank Gollop and Barbara Fraumeni, among others, Jorgenson gradually created a granular new account of the sources of growth, differentiating between inputs of capital (K), labor (L), energy (E), and materials (M). The purchase of services (S) were subsequently broken-out. Hence the KLEMS system of productivity and growth accounting, now used by governments around the world. Jorgenson served as president of the American Economic Association in 2000.

I knew Jorgenson as news people know their subjects, and I have known many of his students, too. I never followed growth accounting closely, though I read Diane Coyle’s beguiling little book GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History (Princeton, 2014), and I was sufficiently absorbed by Fernald’s Intellectual Biography of Jorgenson to suspect that a second golden age of nation income and productivity accounting, or perhaps one of platinum, already has begun. (For an especially artful introduction to the KLEMS system, see Emma Rothschild’s essay, “Where is Capital?” in Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics).

Nor do I know much about early 19th Century naval history. There was, however, something in Jorgenson’s leadership style (and a leader he unmistakably was) that reminded me of the lore surrounding Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson – his precise and formal manner, clipped speech, wry humor, zest in explaining to friends the innovations he prepared, and the admiration and loyalty he elicited from his students and colleagues.

Hearing their stories over the years, I was reminded one day of the signal that Nelson sent his squadrons as the battle of Trafalgar was about to begin – “England expects that every man will so his duty.” Never mind that “the little touch of Dale in the night” sometimes meant wakefulness on nights before examinations. More often his most successful students spoke of encouragement and surprising warmth. Further evidence of the inner man: a 50-year marriage to a professionally successful wife, two children (he worked at home three days a week) and three grandchildren.

If Jorgenson’s sense was that the Swedes, too, would do their duty, apparently they did not conceive their duty quite the same way. Perhaps the pride he took in his work was too obvious to them. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1989, sometimes seen as a consolation prize. Perhaps too much umbrage had been given MIT; there were those 13 volumes of Jorgenson’s collected papers, published with the author’s subvention, five more than those of Paul Samuelson; Griliches had been embarrassed to publish one. (The one-time collaborators (“The Explanation of Productivity Change,” in 1967) were often nominated together for their complementary work.)

Griliches died in 1999; Jorgenson soldiered on, adding to his portfolio the economics of energy, the environment, emerging nations’ development, and even pandemics, via the KLEMS system. He became embedded in the major tax debates of the day. But the attention that theoretical economists paid to increasing returns to scale beginning in the ‘80’s was of little interest to an apostle of neo-classically based empirical analysis.

Jorgenson was sometimes called a “Reedie,” after the selective college he attended, celebrated for a distinctive sort of intellectuality, rivaled by Cal Tech, Swarthmore College and St. Johns College. Some 1,500 undergraduates today, 175 faculty members, providing constant feedback but no grades in real time, a measure thought to encourage hard work and long horizons. Only after they had graduated and applied to graduate schools were their transcripts revealed. Legend had it that Jorgenson was among the handful who over the years had received straight A grades in all his courses, and perhaps a few beyond. Certainly he received encouragement from Carl M. Stevens, a 1951 Harvard PhD in economics then teaching at Reed.

Touring a plaza of his hometown library that had been named for him, the author Phillip Roth was asked if the cold-shoulder from the Swedish Academy bothered him. “Newark is my Stockholm,” Roth replied. Reed College was Jorgenson’s Newark; bi-annual KLEMS project meetings are his Stockholm.

David Warsh, veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Tech presbyopia helped cause crypto apocalypse

Number of Bitcoin transactions per month (logarithmic scale)

“Valhalla in Flames,’’ by Max Bruckner.

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

I have paid little attention to the collapse of crypto-mania because, since it has been clear all along that it was a fraud perpetrated on the greedy and gullible by a coterie of tech-savvy young.

The so-called crypto currencies were simply unregulated banks, their accounting dubious, their lending practices opaque, their valuations in public markets jacked up to preposterous heights by leverage. As Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip wrote in a piece published Nov. 27

While bankruptcy filings aren’t entirely clear, they describe many of the largest creditors as customers or other crypto-related companies. Crypto companies, in other words, operate in a closed loop, deeply interconnected within that loop but with few apparent connections of significance to traditional finance. This explains how an asset class once worth roughly $3 trillion could lose 72% of its value, and prominent intermediaries could go bust, with no discernible spillovers to the financial system.

Block chain technology, on the other hand, has interested me ever since Bitcoin, in 2008, introduced its possibilities to the modern world. Interested, that is, but not enough to do much about it.

It is no accident that the best timeline on the inspiration behind block chain technology I could quickly find last week was published by the Institute of Charters Accountants of England and Wales (ICAEW). That is because the ICAEW, with its 150,000 well-compensated members, and their counterparts enrolled in similar organizations around the world, represent the profession of trusted book-keepers whose livelihoods are threatened in some degree by the new digital technology. Threatened someday, that is – not all at once, but eventually, in 10 to 20 years.

Nor is it surprising that the ICAEW is pretty good on the details of the invention of the threat to the accountancy profession. (Here is a slightly more informative version.) A couple more clicks led to this highly readable digest, The little-known history of block chain, as told by its inventors, by Greg Hall, on a Bitcoin Association Web site.

It turns out that the inventors of the technology behind block chain were working for Bellcore, descendent of the old Bell Laboratories, owned in 1991 by the seven Baby Bells, when they began discussing how it might be possible to time-stamp a digital document. Stuart Haber had a PhD in computer science from Columbia University, Scott Stornetta was a Stanford-trained physicist. They shared an interest in cryptography, a lively topic at the time.

Stornetta knew how easy it was to doctor a digital document without anyone noticing. Society depends on trustworthy records – that is where the bookkeepers came in. But if a transition to entirely digital documents was inevitable, the problem was to create immutable records.

Haber and Stornetta figured out how. Hall writes, “The solution was to use one-way hash functions, take requests for registration of documents (which mean the hash values of the documents), group them into ‘units’ (blocks), build the Merkle tree and create a linked chain of hash values.” They presented their work to an international cryptology conference in Santa Barbara; block chain was born. For a better feel for the inventors, and the work that they did, watch the 10-minute YouTube interview at the end of Hall’s piece.

In 1998 a reclusive Hungarian computer scientist and lawyer named Nick Szabo began experimenting with a digital currency he called Bit Gold. In 2000, German cryptologist and software engineer Stefan Konst published a theory of cryptographically secured chains of data.

But only in 2008 did developers, working under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, publish a workable model of a distributed ledger by then known as block chain. Bitcoin, the killer application, appeared the next year. And in 2014, a block chain 2.0 version was separated from the Bitcoin asset and offered for other kinds of transactions-reporting applications. By then cloud computing was a fact. The human block chain – the accounting profession with their ledgers and books – had been put on notice. Audit robots? Not so fast!

The Bitcoin world, though a reality, is still thronged with crypto-market evangelicals. To get out of it, I turned to Distributed Ledgers: Design and Regulation of Financial Infrastructure and Payment Systems (MIT, 2020), by Robert Townsend, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Townsend is a remarkable scholar. A general equilibrium theorist, trained at the University of Minnesota, he taught at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Chicago for 30 years.

In 1993, he published The Medieval Village Economy: A Study of the Pareto Mapping in General Equilibrium Models (Princeton.) and, in 1997, began his continuing Thailand Project (sample paper: The Village Money Market Revealed: Credit Chains and Shadow Banking). By 2021, he spent a year as the senior research fellow at the Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers’ central bank,” in Basel, Switzerland. And when disparate central bank digital currencies, with their distributed ledgers, are eventually stitched together, that is where the reconciliation will take place.

The cryptocurrency craze, a fraud of memorable proportions, was based on an acute case of what the legendary economic historian Paul David decades ago labeled technological presbyopia – the tendency to see clearly events as they will be, far ahead in time, while overlooking all the necessary steps to get there. For a sense of how long it takes for a new discovery to realize its full technological potential, read Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Crucial Technology (Scribner, 2022), by Chris Miller. Look for a similarly highly readable a book about distributed ledgers to appear in, say, another thirty years.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Tim Ryan says time to ‘Leave the age of stupidity behind us’

“An Allegory of Folly” (early 16th century), by Quentin Matsys

— EC Publications

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the one ostensible mistake I made in what I wrote about the run-up to what did in fact turn out to be a nobody-knows-anything election.

To my mind, the most interesting contest in the country is the Senate election involving 10-term Congressman Tim Ryan and Hillbilly Elegy author J. D. Vance, a lawyer and venture capitalist. That’s because, if Ryan soundly defeats Vance, he’s got a good shot at becoming the Democratic presidential nominee in 2024.

Even now I don’t think that I was altogether wrong.

Thanks to the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, we know why Ryan lost. Vance, who was on the ballot because Donald Trump endorsed him, trailed Ryan by significant margins until mid-summer. That was when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell invested more than $32 million in the Ohio Senate race, via a super-PAC he controlled, 77 percent of all Republican campaign media spending in the Ohio election after mid-August. Most of it was negative “voter education,” enough to tip the balance against “taxing-Tim” for having voted for various Biden measures. The power of money in American elections may be a scandal, but by now it has been well-established by the Supreme Court as a fact of life.

It seems nearly certain to me that the next president will be someone born in the ‘70’s, not the ‘40’s. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat was probably correct when he wrote last week that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is likely to be the Republican nominee. DeSantis, 44, was born in 1978.

Douthat may have been wrong, however, in thinking that DeSantis’s “sweeping success” in his re-election campaign validated the theory that “normal” doesn’t have to mean “squishy.” The tough-guy approach worked well in Florida. DeSantis was “an avatar of cultural conservatism, a warrior against the liberal media and Dr. Anthony Fauci, a politician ready to pick a fight with Disney if that’s what the circumstances require.”

But a better-mannered Donald Trump may not be what the majority of voters will be looking for in the next election. Tim Ryan, 49, was born in 1973. If you have time, and want a lift, watch Ryan’s 15-minute concession speech to get a feel for the man. Pay special attention to the six-minute mark, where Ryan speaks to the audience beyond the room he is in.

The words in that middle portion of that speech strike a powerful chord: “This country, we have too much hate, too much anger, there is way too much fear, way too much division. We need more love, more compassion, more concern for each other. These are important things. We need forgiveness, we need grace, we need reconciliation. We do have to leave the age of stupidity behind us.”

There are many question to be answered. First among them: are Ryan and his family willing to undertake a two-year front porch campaign? If so, a 10-term former congressman has a reasonable chance to win both the Democratic Party’s nomination, and the 2024 election itself.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

David Warsh: Will the GOP abandonUkraine soon after the mid-term election?

— Map by Viewsridge

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Only a few days before an election is no time to be a columnist. This column is written some distance from Washington, D.C., but Edward Luce, of the Financial Times, is there in the thick of things. On Oct. 29, in “America’s Brittle Consensus on Ukraine,’’ he wrote “In the Republican quest to make a scorched earth of Biden’s presidency nothing will be sacred, including Ukraine’s military pipeline.” The “pro-Putin wing” of the GOP is still a minority, Luce added, but “almost every Republican will back {likely next House Speaker Kevin} McCarthy’s likely effort to impeach Biden and hold the U.S. debt ceiling hostage to their demands.”

That much, at least, remains to be seen. The presumptive speaker will settle on his plans only after the election results are known and thoroughly construed. Until then there remains a possibility that McCarthy’s Trump-based agenda will dissipate in a mood of grudging forgiveness following what may turn out to be a nobody-knows-anything election.

“The fact remains, however, that fifty-seven House Republicans and eleven senators voted against Biden’s $40 billion Ukraine aid package earlier this year. And though it hasn’t yet sunk in, Russian president Vladimir Putin took an active hand in the US election Thursday when, in an important speech, he asserted there were

“[T]wo Wests – at least two and maybe more but two at least – the West of traditional, primarily Christian values, freedom, patriotism, great culture and now Islamic values as well – a substantial part of the population in many Western countries follows Islam. This West is close to us in some things. We share with it common, even ancient roots. But there is also a different West – aggressive, cosmopolitan, and neocolonial… a tool of neoliberal elites [embracing what I believe are strange and trendy ideas like dozens of genders or gay pride parades].’’

He might as well have identified them as being, in his view, Republicans and Democrats.

Putin believes this is the basis for his war on Ukraine. It may be MAGA’s view as well. I don’t believe it is McCarthy’s. It certainly is not mine. But it will take time to work out the distinction. Less than a week before a very important election is no time to try.

Meanwhile, I’ve been been reading Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate (Yale, 2021), by M.E. Sarotte; Macroeconomic Policies for Wartime Ukraine (Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2022), by Kenneth Rogoff, Maurice Obstfeld, and seven others; “Warfare without the State,’’ Adam Tooze’s recent criticism of the CEPR plan; and “Russia’s Crimea Disconnect’’, by Yale historian Timothy Snyder; and Johnson’s Russia List, more or less daily.

Halloween was scarier than usual this year.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: The WSJ ‘contains multitudes’

On Chicago’s Lakefront.

— Photo by Alanscottwalker

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

A headline on a story Oct. 21 in the in The Wall Street Journal revealed “Chicago’s Best-Kept Secret: It’s a Salmon Fishing Paradise; Locals crowd into inlets off Lake Michigan to catch fish imported from West Coast to counter effects of invasive species.”

Between vignettes of jubilant fishermen braving the lake-front weather, reporter Joe Barrett offered a concise account of how Great Lakes wildlife managers have coped with successive waves of invasive species over eighty years of globalization. In the beginning were native lake trout, apex predators thriving on shoals of perch. Sea lampreys arrived in the Forties, through the Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario with Lake Erie. The blood-sucking eels devastated the trout population, while alewives, another invasive species, grew disproportionately large with no other to prey on them.

Authorities controlled the lampreys with a new pesticide in the mid-Sixties, and imported Coho and later Chinook salmon from the West Coast to rejuvenate sport fishing. Fingerling salmon hatched in downstate Illinois nurseries were released in Chicago harbors, to return to the same waters to spawn at maturity. Meanwhile, ubiquitous European mussels, released from ballast tanks of ships entering the lakes via the St. Lawrence Seaway, improved water clarity, but consumed nutrients needed by small fish. As a native of the region, I remember every wave.

A Coho salmon.

I was struck by the artful sourcing of Barrett’s story. He quoted fishermen Andre Brown, “a 51-year-old electrician from Oak Park;” Martin Arriaga, “a 59-year-old truck driver from the city’s Chinatown neighborhood,” and Blas Escobedo, 56, “a carpet installer from the Humboldt Park neighborhood.”

Providing the narrative were Vic Santucci, Lake Michigan program manager for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and Sergiusz Jakob Czesny, director of the Lake Michigan Biological Station of the Illinois Natural History Survey and the Prairie Research Institute. The Illinois Department of Health chimed in with its recommendation: PCB concentration in the bigger fish meant no more than one meal a month.

Barrett did not mention the dangerous jumping Asia carp that now threaten to enter Lake Michigan; nor the armadillos, creeping north from Texas into Illinois, with global warming: much less the escalating crime rates in Chicago, which have McDonald’s threatening to move out of the city. But then his was a story about fishery management. And that’s what I like about the WSJ: it contains multitudes.

Earlier last week I had sought to convey to visiting friends the different sensibilities among the newspapers I read. I prize The New York Times for any number of reasons, but its concern for the future of democracy in America often seems overwrought. I look to The Washington Post for editorial balance (never mind the “Democracy Dies in Darkness” motto), and to the Financial Times for sophistication. But it is hard to exaggerate how much I enjoy The Wall Street Journal. I worked there for a time years ago; that surely has something to do with it. But I think it is the receptivity of its news pages I so admire. Like Joe Barrett’s fish story, its sentiments are inclusive. Read it if you have time.

Despites its sale to conservative newspaper baron Rupert Murdoch, the WSJ has preserved the separation between sensible news pages, its worldly cultural and lifestyle coverage, and its fractious editorial pages. Those editorial pages are still recovering from their enthusiasm for Donald Trump, and I sometimes think as I read them that they pose a threat to democracy, if only by their preference for derision. But still I read them, so they must be doing something right.

Barely two weeks remain before the mid-term elections. The races that interest me most are those seeking common ground: Ohio, Alaska, Pennsylvania, and Oregon. There will be time afterwards to sift the results. Is American democracy in danger? I doubt it. E pluribus unum! with a certain amount of thoughtful guidance along the way.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: Exploring ‘quantum weirdness’

Main building of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, in Stockholm.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I spent its time last week reading up quantum entanglement. Instantaneous connections between far-apart locations – the possibility of “spooky action at a distance” that was dismissed by Einstein – turns out to have become the basis of quantum computing and fail-safe cryptography.

First I read The New York Times story: Nobel Prize in Physics Is Awarded to 3 Scientists for Work Exploring Quantum Weirdness. by Isabella Kwai, Cora Engelbrecht and Dennis Overbye. I especially liked the part about John Clauser’s duct-tape and spare-parts experiment in a basement at the University of California at Berkeley that opened the laureates’ path to the prize. (Stories in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each had distinctive strong points as well.)

The Times story led me back to MIT physicist/historian David Kaiser and his 2011 book, How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival. I didn’t read it when it appeared, having a mild prejudice against hot tubs, psychedelic drugs and saffron robes. I was wrong. I ordered a copy last week.

Next was a Science magazine piece from 2018 by Gabriel Popkin that showed the discoveries well on their way to acceptance: Einstein’s ‘spooky action at a distance’ spotted in objects almost big enough to see.

Then came a Scientific American article, The Universe Is Not Locally Real, and the Physics Nobel Prize Winners Proved It, by David Garisto, that seemed to me to offer the most lucid explanations of the profound uncertainties involved. These are more daunting than ever in the face of irresistible technological evidence that they exist.

At that point I returned to the Nobel announcement, and skimmed the citations in the scientific background to see if the story was as I had been taught (by my mother, Annis Meade Warsh, who was herself entangled with science and religion!). Sure enough there among the citations was the history of the argument, from Erwin Schrödinger, in 1935; to Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, in 1935; to David Bohm, in 1951; to John Stewart Bell, in 1964; and to Stuart Freedman and Clauser (the former having been Clauser’s graduate student), in 1972. Imagine my surprise last year when I discovered the distinguished historian of physics John Heilbron was reading Bohm’s last book, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, the very title recommended to me by my mother not long after its publication, in 1980. I checked Wholeness out from the library. I could not fathom the implicated order.

In fact, the most beguiling explication of the prize I found was the 15-minute talk that Nobel Committee member Thors Hans Hansson gave to journalists after the prize announcement in Stockholm last week. The 72-year old theoretical physicist personified the combination of collective energy, sobriety and delight that enables the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to keep the world abreast of developments, year after year.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: To come back, print editions of newspapers must solve intricate production problem

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The off-lead story in the Sept. 18 New York Times, illustrated by a fraying American flag, was one of a series: “Democracy Challenged: twin threats to government ideals put America in uncharted territory.” Senior writer David Leonhardt identified two distinct perils: a movement in one major party to refuse to accept election defeat, and a Supreme Court at odds with public opinion. Leonhardt’s argument was well reasoned and deftly written, enough to fill four pages after the jump.

To my mind, though, The Times is overlooking a problem even more fundamental to the conduct of American democracy: the concentration of power in the quartet of daily newspapers that remain at the top of the first-draft-of-history narrative chain. The loss of diversity of news and opinion among metropolitan newspapers in the 50 American states over the last thirty years has not been well understood.

Media proprietor Rupert Murdoch bought The Wall Street Journal from the Bancroft family, in 2007. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post from the Graham family, in 2012. Japanese media group Nikkei acquired the Financial Times from Pearson publishers, in 2015. The New York Times, a fifth-generation family-controlled firm, retains its independence. But Bloomberg LP, an all-digital software analytics and media company, also based in midtown Manhattan, remains looking over its shoulder.

Meanwhile, major metropolitan daily newspapers across the country have been sold and diminished, or collapsed altogether, in the 32 years since the World Wide Web was introduced. These include the Chicago Tribune and its many subsidiaries, among them the Los Angeles Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Hartford Courant and the New York Daily News; The Providence Journal; The Philadelphia Inquirer and 31 other Knight Ridder newspapers, including The Miami Herald and San Jose’s Mercury News; Cleveland’s Plain Dealer, Portland’s Oregonian and New Orleans’s Times-Picayune, among the Newhouse newspaper chain; the Louisville Courier-Journal; the Arizona Republic; Las Vegas Sun, and Dean Singleton’s Denver Post. The Daily Bee, founded in Sacramento in 1857, part of all but the last surviving family-owned newspaper chain, declared bankruptcy in 2020, though the Atlanta Journal-Constitution remains the flagship of Cox Enterprises. Only Texas and Florida maintain several competitive metropolitan newspapers. The Christian Science Monitor ceased publishing a paper edition in 2009, while maintaining a digital presence.

What happened? Google and Facebook entered the advertising business. Antitrust newsletter writer Matt Stoller recently described Google’s rollup of the search-intermediary industry over the course of a decade, notably its 2007 acquisition of DoubleClick, into the voracious advertising sales business that the former “free” search engine enterprise has become. Facebook did much the same. The result was that newspapers lost some 80 percent of their advertising revenues in a decade. More than 2,000 papers went out of business altogether.

In a similar vein, The New Goliaths: How Corporations Use Software to Dominate Industries, Kill Innovation, and Undermine Regulation (Yale, 2022), by James Bessen, makes a compelling case that “dominant firms have used proprietary technology to achieve persistent competitive advantages and persistent market dominance,” by more effectively managing market complexity in industries of all sorts.

Strengthening antitrust enforcement is a good idea, Bessen says, but breaking up firms is unlikely to solve the “superstar problem.” A more effective solution has to do with opening up access to knowledge, which means addressing ubiquitous intellectual-property bottlenecks. Market-driven unbundling – the process that, in the 1970s, led IBM to open its proprietary software to independent applications, and, in the Oughts, Amazon to make its information technology software available to other vendors on its proprietary servers – offer more promising possibilities, he asserts in a closing chapter. Bessen heads a research initiative at Boston University’s Law School. The New Goliaths is an important book. Let’s hope it get the attention it deserves.

American democracy is not doomed to a future dominated by four or five national newspapers. There is reason to believe that the market for home-delivered newsprint newspapers is much broader than it now seems, though it may take years to revive it. Radio returned to prosperity after television advertising all but destroyed its formerly lucrative advertising business. Newsprint thrived for nearly a hundred years despite the entry of both.

To come back from the online onslaught, however, print newspapers must solve an intricate coordination problem, involving every aspect of the business. These include the cost of newspaper production, from newsprint to software to printing facilities; the riddle of subscription pricing; the restoration of home delivery networks; and the reconstruction of advertising sales. Moreover, the new newsprint goliaths must cooperate with big city dailies seeking to regain market share if the problem is to be solved.