David Warsh: Eating Instagram; McKinsey and OxyContin scandal

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I was as surprised as anyone when a panel of prominent judges earlier this month chose No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, by Sara Frier, of Bloomberg News, as the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year, so I ordered it. The publisher, Simon & Shuster, was surprised, too: the book has not yet arrived. So I re-read FT staffer Hannah Murphy’s review from last April.

The book sounds absorbing enough: how Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom agreed to sell his start-up for $1 billion over a backyard barbecue at Mark Zuckerberg’s house and then watched in distress as Facebook bent the inventive photography app to purposes of its own. He finally walked away from the company he started, an enterprise that Frier called “a modern cultural phenomenon in an age of perpetual self-broadcasting” brought low by Facebook’s quest for global domination.

FT editor Roula Khalaf praised the book for tackling “two vital issues of our age: how Big Tech treats smaller rivals and how social-media companies are shaping the lives of a new generation.” In a beguiling online profile last summer, Frier explained how “everything changed” for technology reporters covering social media after the 2016 presidential election. Remembering the embrace-extend-extinguish tactics pioneered by Microsoft, antitrust authorities will also want to take a look.

There is, however, a larger issue about the contest itself. Given the temper of the times, I had thought either Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, both of Princeton University, or Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, by Rebecca Henderson, of the Harvard Business School, powerful books of unusual gravity, might capture the blue ribbon. Both specifically criticize a major McKinsey client, Purdue Pharma, and both vigorously reject the market fundamentalism that often has been imputed to the values of the secretive firm in recent decades – “shareholder value” as the only legitimate compass of corporate conduct and all that.

Granted, the prize is said by its sponsors to reward “the most compelling and enjoyable insight into modern business issues” of a given year. Previous panels have interpreted their instructions in a wide variety of ways. A McKinsey executive last year joined the judging panel. I wondered if the other members, none of them strangers to McKinsey’s lofty circles, had successfully argued to include the two critical books on the short list, before selecting a title more narrowly about “modern business issues” to avoid embarrassment to the sponsor. The awarding of literary prizes as it actually works on the inside is sometimes said to be very different from how it may look from the outside.

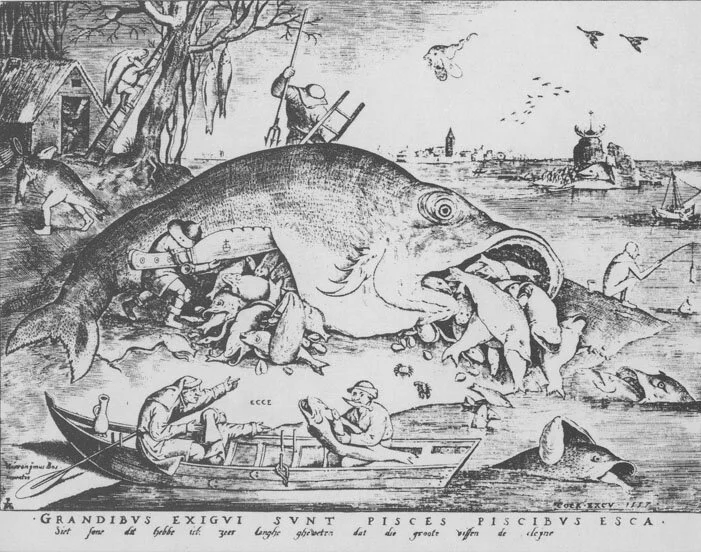

An OxyContin pill

Whatever the case, the judges could not have known about the news that broke the day before their decision was announced. The New York Times reported that documents released in a federal bankruptcy court had revealed that McKinsey & Co. was the previously unidentified-management consulting firm that has played a key role in driving sales of Purdue’s OxyContin “even as public outrage grew over widespread overdoses” that had already killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

In 2017, McKinsey partners proposed several options to “turbocharge” sales of Purdue’s addictive painkiller. One was to give distributors rebates of $14,810 for every OxyContin overdose attributed to pills they had sold. Purdue executives embraced the plan, though some expresses reservations. (Read The New York Times story: the McKinsey team’s conduct was abhorrent.) Spokesmen for CVS and Anthem, themselves two of McKinsey’s biggest clients, have denied receiving overdose rebates from Purdue, according to reporters Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe.

Moreover, after Massachusetts’s attorney general sued Purdue, Martin Elling, a senior partner in McKinsey’s North American pharmaceutical practice, wrote to another senior partner, “It probably makes sense to have a quick conversation with the risk committee to see if we should be doing anything” other than “eliminating all our documents and emails. Suspect not but as things get tougher there someone might turn to us.” Came the reply: “Thanks for the heads-up. Will do.” Elling has apparently relocated his practice from New Jersey to McKinsey’s Bangkok office, The Times’s reporters write.

Last week The Times reported that McKinsey & Co. issued an unusual apology for its role in OxyContin sales and vowed a full internal review. Sen. Josh Hawley (R.- Mo.) wrote the firm asking if documents had been destroyed. “You should not expect this to be the last time McKinsey’s work is referenced,” the firm wrote in an internal memo to employees. “While we can’t change the past we can learn from it.”

Another rethink is for the FT. The newspaper started its award in 2005, with Goldman Sachs as its co-sponsor. Tarnished by the 2008 financial crisis and the aftermath, the financial-services giant bowed out after 2013 and McKinsey took over. The enormous consulting firm is famous mainly for the anonymity on which it insists, but the Purdue Pharma scandal isn’t the first time that McKinsey has been in the news recently, especially for its engagements abroad, in Puerto Rico and Saudi Arabia. A thorough audit of its practices, reinforced by outside institutions, is overdue. In an age of mixed economies and transparency, McKinsey’s business model of mutually-contracted secrecy between the firm and the client seems outdated

Why the need for sponsorship? It would seem to be mainly a form of cooperative advertising. The cash awards to authors are lavish: £30,000 to the winner, £10,000 to each of five finalists, undisclosed sums to the judges, publicists and for advertising. That makes McKinsey’s investment a spectacular bargain, but it is something of a poisoned chalice for the FT.

The prize’s reputation as recognizing entertaining writing about important business topics is well established. Why not dispense with the money and influence? Who knows what McKinsey does and for whom? Isn’t trustworthy filtering of information the very essence of the newspaper’s business?

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

Kayla Kitson: Real wages decline after GOP tax 'reform'

The Trump-GOP tax law was sold as a boon for the middle class. But many months after its passage, there are no signs that working Americans are getting the pay raise they were promised.

The Trump administration claimed the corporate tax cuts would eventually lead to wage increases of up to $9,000 a year for ordinary workers. But so far, workers’ wages remain stagnant.

Tracking by Americans for Tax Fairness shows that only about 400 out of America’s 5.9 million employers have announced any wage increases or one-time bonuses related to the tax cuts. That’s about 0.007 percent.

In fact, real wages have actually declined since last year after accounting for higher gasoline prices, prescription-drug prices and other rising costs.

If that weren’t bad enough, Trump and the GOP now want to come after the services that working families rely on.

Shortly after signing the tax cut package that will add nearly $2 trillion to the deficit over a decade, Trump proposed a budget that would cut $1.3 trillion for Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Cart Act. The House Republican budget went even further, proposing $2.1 trillion in health-care cuts.

Both budget proposals contained hundreds of billions more in cuts to food assistance, income security, education, and more.

Working families are seeing little benefit from the Trump-GOP tax giveaway — and would be devastated by the cuts to services that have been proposed to help pay for it. But a few people are basking in their new tax-cut windfalls:

President Trump: Though he claimed his tax plan would “cost him a fortune,” the new law will undoubtedly make him one.

Trump refuses to release his tax returns, so we can’t know his exact savings. But he’ll benefit greatly from the lower top individual tax rate, the lower corporate-tax rate, and especially from the 20 percent deduction for “pass-through” business income (income from S corporations, partnerships, limited liability companies, and sole proprietorships that’s taxed at the individual rather than the corporate level).

The Trump Organization, which is a collection of 500 pass-throughs, could save over $20 million a year from that deduction alone. And the law gifted Trump’s industry — real estate — with myriad new loopholes.

Members of Congress: 53 Republican members of Congress who voted for the law could each enjoy $280,000 a year in tax cuts on average.

This includes millions of dollars each for Representatives Vern Buchanan (R.-Fla.) and Diane Black (R.-Tenn.), who serve on the committee that wrote the law. The day that Rep. Buchanan — who could get up to $2.1 million in annual tax cuts — voted in favor of the tax cut bill, he rewarded himself with a multimillion-dollar yacht.

Big Pharma: Prescription-drug companies have profited handsomely in recent years by price-gouging customers and public health programs like Medicare and Medicaid. They also shifted lots of those profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes.

The Trump-GOP tax law rewards Big Pharma for its years of offshore tax avoidance with a steep discount on the amount due on its stash of offshore profits. Americans for Tax Fairness estimates the 10 largest American drug firms will save a collective $76 billion from this provision alone.

Big Pharma will also benefit from the new lower corporate tax rate and a new international tax regime that taxes future foreign profits at half the domestic profits rate.

While this elite group of tax-law winners are enjoying their tax-cut spoils, the majority of Americans are left holding the bag.

Kayla Kitson is research and policy director at Americans for Tax Fairness.

Jim Hightower: Don't be fooled by Trump's drug-price ploy

From OtherWords.org

President Trump is said to see himself as a sort of Teddy Roosevelt. TR, however, was known as a trust buster, while DT has become known as a trust hugger.

We recently saw the hugger in action when he held a PR event to ballyhoo 50 proposals to stop Big Pharma from gouging American consumers with monopolistic drug pricing.

People are rightly outraged that pill-peddling giants exploit patients who have life-threatening diseases and routinely jack up prices on common drugs by some 10 percent a year. As a presidential candidate, Trump jumped on this hot issue, accusing drug makers of “getting away with murder.”

So, now with typical modesty, he’s revealed his plan to stop the rip-offs, calling his 50 proposals the “most sweeping action in history to lower the price of prescription drugs for the American people.”

Yeah, “sweeping” — as in sweeping the problem under the White House rug.

Fifty is just a political number meant to puff-up Trump’s plan as something BIG. But as one congressional Democrat pointed out, all 50 amount to “a sugar-coated nothing pill.” Nowhere on that list of 50 things was Trump’s own campaign promise to use the purchasing power of Medicare to negotiate lower prices for seniors.

Far from feeling punished, Big Pharma itself felt it had gotten a warm presidential hug. Drug company stock prices went up immediately after the presidential speech.

It’s really no surprise that Trump is letting these corporate profiteers continue “getting away with murder.” After all, political posturing aside, he’s stacked his administration with drug industry executives like Alex Azar, a former Eli Lily honcho who is now Trump’s secretary of health.

How revealing that Azar was standing right behind the president at the White House media event, beaming and applauding as Trump announced… well, a lot of nothing.

Jim Hightower, an OtherWords columnist, is a radio commentator, writer, and public speaker. He’s also editor of the populist newsletter, The Hightower Lowdown

Domenica Ghanem: Pharma companies are the authors of the opioid crisis

Via OtherWords.org

At a recent rally in New Hampshire, Donald Trump called for the death penalty for drug traffickers as part of a plan to combat the opioid epidemic in the United States. At a Pennsylvania rally a few weeks earlier, he called for the same.

Now his administration is taking steps toward making this proposal a reality. Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions issued a memo on March 21 asking prosecutors to pursue capital punishment for drug traffickers — a power he has thanks to legislation passed under President Clinton.

Time and again, these punitive policies have proven ineffective at curbing drug deaths. That’s partly because amping up the risk factor for traffickers makes the trade all that more lucrative, encouraging more trafficking, not less.

But it’s also because these policies don’t address the true criminals of the opioid crisis: Big Pharma.

If Trump really wanted to help, he’d put the noose around drug-making and selling giants like Purdue Pharma, McKesson, Insys Therapeutics, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen, and others.

The president knows this, in a way. These companies “contribute massive amounts of money to political people,” he said at a press conference in October 2017 — even calling out Mitch McConnell, who was standing beside him, for taking that money. Pharmaceutical manufacturers were “getting away with murder,” Trump complained in the same speech.

For once, he’s wasn’t wrong.

The pharmaceutical industry spends more than any other industry on influencing politicians, with two lobbyists for every member of Congress. Nine out of ten House members and all but three senators have taken campaign contributions from Big Pharma.

It’s not just politicians they shell out for.

Opioid pioneer Purdue Pharma, the creator of OxyContin, bankrolled a campaign to change the prescription habits of doctors who were wary of the substance’s addictive properties, going so far as to send doctors on all-expense-paid trips to pain-management seminars. The family that started it all is worth some $13 billion today.

From 2008 to 2012, AmerisourceBergen distributed 118 million opioid pills to West Virginia alone. That’s about 65 pills per resident. In that same time frame, 1,728 people in the state suffered opioid overdoses.

McKesson — the fifth largest company in the U.S., with profits over $192 billion — contributed 5.8 million pills to just one West Virginia pharmacy.

Meanwhile, five companies contributed more than $9 million to interest groups for things like promoting their painkillers for chronic pain and lobbying to defeat state limits on prescribing opioids.

These companies don’t stop at promoting opioids. They also spend big on stopping legislation that would actually help curb opioid use.

Insys Therapeutics, a company whose founder was indicted for allegedly bribing doctors to write prescriptions for fentanyl (a substance 50 times stronger than heroin), spent $500,000 to stop marijuana legalization in Arizona in 2016.

In response, cities and states from New York City to Ohio are suing pharmaceutical companies for their role in the deaths of tens of thousands of Americans every year. It’s time for the federal government to get behind them.

Of course, going after these companies isn’t going to eliminate opioid abuse on its own. That will take combating the root social and economic causes that lead to so many deaths of despair.

But it’s clear who the real profiteers of the opioid epidemic are. If Trump wanted to get real about curbing incentives for selling opioids, he’d turn away from street dealers and target the real opioid-producing industry.

Domenica Ghanem is the media manager of the Institute for Policy Studies.

Llewellyn King: The medical-research crisis

The Bermuda Triangle is where aircraft, ships and people disappear. That is as may be.

Another less-mysterious triangle swallows good ideas and great science, and leaves people vulnerable. It is the triangle that is formed by the way we conduct medical research in the United States, the role of the pharmaceutical industry in that research and the public’s perception, driven by political ideology, of how it works.

The theory is that the private sector does research, and everything else, better than the government. But the truth is the basic research that has put the United States ahead of the rest of the world -- as a laboratory for world-changing science and medicine -- has been funded by the government.

It is the government that puts social need ahead of anticipated profit. It is the government that puts money into obscure but important research. And it is the government which will keep the United States in the forefront of discovery in science and medicine.

It is no good for politicians to rant about the importance of children taking more and harder math and science courses. Before they open their mouths, they should look at the indifferent way in which we treat mathematicians and scientists. We treat them as little better than day laborers, called on to do work ordered by government, then laid off as political chiefs change their minds.

A career in research, whether in physical sciences (such as astrophysics) or medical sciences (such as cell biology) is a life of insecurity. Had we put the dollars behind Ebola research years ago (the disease was first identified in 1976), we would not now be watching what may become a tsunami of death raging across Africa, and possibly the world. Shame.

Any gifted young person going into research nowadays needs career counseling. They will be expected to give their all, with poor pay and long hours, to serve mankind. Then the funding will be cut or the research grant will not be renewed, and they will be on the fast track from idealism to joblessness.

You may have heard of the celebrated virus hunter, W. Ian Lipkin, M.D., director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health, because he has been called on for expertise in Ebola. What you might not know is that Lipkin is so starved of funding that he has had to use crowd-funding to support his research on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, the ghastly disease commonly known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS).

Nothing is more damaging to research than funding instability. The universities and many research laboratories -- including those run by the government -- operate like concertinas. They expand and contract according the whim of Congress, not the needs of science, public health or American leadership.

Industry is not the answer to absent government. Pharmaceutical companies spend an astonishing amount -- up to $3 billion -- to bring a new drug to market. But traditionally agencies of government, particularly the National Institutes of Health, seed research where the social need is apparent or where the discoveries, like an Ebola treatment, are defensive. Big Pharma often comes in later, as the developer of a drug, not the discoverer. Discovery starts with lowly dedication.

Sometimes the cost and risk initially is just too high for private institutions to take a therapy from the laboratory to the doctor’s office. Most drugs, contrary to legend, begin in the research hospitals, the universities and in government laboratories long before drug companies develop manufacturing techniques and shoulder the giant cost of clinical trials.

Developing new drugs has become too expensive for the private sector, according to a recent article in Nature. The magazine says the drug pipeline for new antibiotics, so vital in fighting infectious disease, has collapsed as Big Pharma has withdrawn. The latest to leave is Novartis, which has ceased work on its tuberculosis drug and handed it over to a charity coalition.

Government funding for medical research is now at a critical stage. It has flat-lined since 2000, as medical costs have ballooned. Also, congressional sequestration has hit hard.

Stop-and-start funding breaks careers, destroys institutional knowledge and sets the world back on its scientific heels. That is to say nothing of the sick, like those with Ebola or CFS, who lie in their beds waiting for someone to do something.

<em> Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of <em>White House Chronicle</em>, on PBS. His e-mail is lking@kingpublishing.com.</em>