Elisabeth Rosenthal: Primary- care crisis intensifies

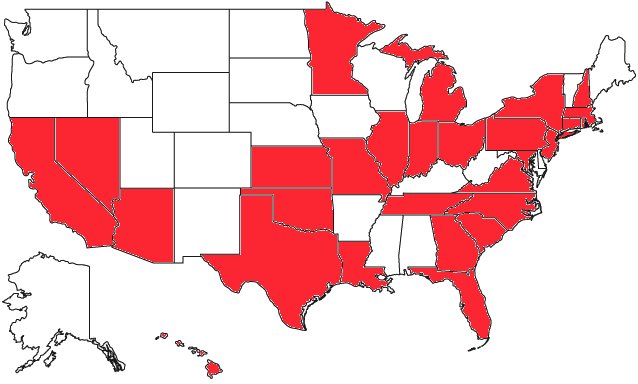

These measurements of health-care service levels for specific areas of the U.S. came out in June 2020 through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

States in red have Rhode Island-based CVS’s Minute Clinics, which are cutting into traditional primary-care practices.

“We have a specialty-driven system. Primary care is seen as a thankless, undesirable backwater.”

— Michael L. Barnett, M.D., health-systems researcher and primary-care physician in the Harvard Medical School system

I’ve been receiving an escalating stream of panicked emails from people telling me their longtime physician was retiring, was no longer taking their insurance, or had gone concierge and would no longer see them unless they ponied up a hefty annual fee. They have said that they couldn’t find another primary-care doctor who could take them on or who offered a new-patient appointment sooner than months away.

Their individual stories reflect a larger reality: American physicians have been abandoning traditional primary- care practice — internal and family medicine — in large numbers. Those who remain are working fewer hours. And fewer medical students are choosing a field that once attracted some of the best and brightest because of its diagnostic challenges and the emotional gratification of deep relationships with patients.

The percentage of U.S. doctors in adult primary care has been declining for years and is now about 25 percent — a tipping point beyond which many Americans won’t be able to find a family doctor at all.

Already, more than 100 million Americans don’t have usual access to primary care, a number that has nearly doubled since 2014. One reason our coronavirus vaccination rates were low compared with those in countries such as China, France, and Japan could be because so many of us no longer regularly see a familiar doctor we trust.

Another telling statistic: In 1980, 62 percent of doctor’s visits for adults 65 and older were for primary care and 38 percent were for specialists, according to Michael L. Barnett, a health-systems researcher and primary- care doctor in the Harvard Medical School system. By 2013, that ratio had exactly flipped and has likely “only gotten worse,” he said, noting sadly: “We have a specialty-driven system. Primary care is seen as a thankless, undesirable backwater.” That’s “tragic,” in his words — studies show that a strong foundation of primary care yields better health outcomes overall, greater equity in health-care access, and lower per-capita health costs.

One explanation for the disappearing primary-care doctor is financial. The payment structure in the U.S. health system has long rewarded surgeries and procedures while shortchanging the diagnostic, prescriptive and preventive work that is the province of primary care. Furthermore, the traditionally independent doctors in this field have little power to negotiate sustainable payments with the mammoth insurers in the U.S. market.

Faced with this situation, many independent primary-care doctors have sold their practices to health systems or commercial management chains (some private-equity-owned) so that, today, three-quarters of doctors are now employees of those outfits.

One of them was Bob Morrow, who practiced for decades in the Bronx. For a typical visit, he was most recently paid about $80 if the patient had Medicare, with its fixed-fee schedule. Commercial insurers paid significantly less. He just wasn’t making enough to pay the bills, which included salaries of three employees, including a nurse practitioner. “I tried not to pay too much attention to money for four or five years — to keep my eye on my patients and not the bottom line,” he said by phone from his former office, as workers carted away old charts for shredding.

He finally gave up and sold his practice last year to a company that took over scheduling, billing and negotiations with insurers. It agreed to pay him a salary and to provide support staff as well as supplies and equipment.

The outcome: Calls to his office were routed to a call center overseas, and patients with questions or complaining of symptoms were often directed to a nearby urgent care center owned by the company — which is typically more expensive than an office visit. His office staff was replaced by a skeleton crew that didn’t include a nurse or skilled worker to take blood pressure or handle requests for prescription refills. He was booked with patients every eight to 10 minutes.

He discovered that the company was calling some patients and recommending expensive tests — such as vascular studies or an abdominal ultrasound — that he did not believe they needed.

He retired in January. “I couldn’t stand it,” he said. “It wasn’t how I was taught to practice.”

Of course, not every practice sale ends with such unhappy results, and some work out well.

But the dispirited feeling that drives doctors away from primary care has to do with far more than money. It’s a lack of respect for nonspecialists. It’s the rising pressure to see and bill more patients: Employed doctors often coordinate the care of as many as 2,000 people, many of whom have multiple problems.

And it’s the lack of assistance. Profitable centers such as orthopedic and gastroenterology clinics usually have a phalanx of support staff. Primary-care clinics run close to the bone.

“You are squeezed from all sides,” said Barnett.

Many ventures are rushing in to fill the primary-care gap. There had been hope that nurse practitioners and physician assistants might help fill some holes, but data shows that they, too, increasingly favor specialty practice. Meanwhile, urgent-care clinics are popping up like mushrooms. So are primary-care chains such as One Medical, now owned by Amazon. Dollar General, Walmart, Target, CVS Health and Walgreens have opened “retail clinics” in their stores.

Rapid-fire visits with a rotating cast of doctors, nurses, or physician assistants might be fine for a sprained ankle or strep throat. But they will not replace a physician who tells you to get preventive tests and keeps tabs on your blood pressure and cholesterol — the doctor who knows your health history and has the time to figure out whether the pain in your shoulder is from your basketball game, an aneurysm, or a clogged artery in your heart.

Some relatively simple solutions are available, if we care enough about supporting this foundational part of a good medical system. Hospitals and commercial groups could invest some of the money they earn by replacing hips and knees to support primary care staffing; giving these doctors more face time with their patients would be good for their customers’ health and loyalty if not (always) the bottom line.

Reimbursement for primary-care visits could be increased to reflect their value — perhaps by enacting a national primary care fee schedule, so these doctors won’t have to butt heads with insurers. And policymakers could consider forgiving the medical school debt of doctors who choose primary care as a profession.

They deserve support that allows them to do what they were trained to do: diagnosing, treating, and getting to know their patients.

The United States already ranks last among wealthy countries in certain health outcomes. The average life span in America is decreasing, even as it increases in many other countries. If we fail to address the primary care shortage, our country’s health will be even worse for it.

Elisabeth Rosenthal is a KFF Health News reporter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal: erosenthal@kff.org, @RosenthalHealth

Arthur Allen: Not profitable enough for CVS

Parenteral formula

NEW YORK — The fear started when a few patients saw their nurses and dietitians posting job searches on LinkedIn.

Word spread to Facebook groups, and patients started calling Coram CVS, a major U.S. supplier of the compounded IV nutrients on which they rely for survival. To their dismay, CVS Health, based in Woonsocket, R.I., confirmed the rumors on June 1: It was closing 36 of the 71 branches of its Coram home-infusion business and laying off about 2,000 nurses, dietitians, pharmacists and other employees.

Many of the patients left in the lurch have life-threatening digestive disorders that render them unable to eat or drink. They depend on parenteral nutrition, or PN — in which amino acids, sugars, fats, vitamins, and electrolytes are pumped, in most cases, through a specialized catheter directly into a large vein near the heart.

The day after CVS’s move, another big supplier, Optum Rx, announced its own consolidation. Suddenly, thousands would be without their highly complex, shortage-plagued, essential drugs and nutrients.

“With this kind of disruption, patients can’t get through on the phones. They panic,” said Cynthia Reddick, a senior nutritionist who was let go in the CVS restructuring.

“It was very difficult. Many emails, many phone calls, acting as a liaison between my doctor and the company,” said Elizabeth Fisher Smith, a 32-year-old public-health instructor in New York City, whose Coram branch was closed. A rare medical disorder has forced her to rely on PN for survival since 2017. “In the end, I got my supplies, but it added to my mental burden. And I’m someone who has worked in health care nearly my entire adult life.”

CVS had abandoned most of its less lucrative market in home parenteral nutrition, or HPN, and “acute care” drugs like IV antibiotics. Instead, it would focus on high-dollar, specialty intravenous medications like Remicade, which is used for arthritis and other autoimmune conditions.

Home and outpatient infusions are a growing business in the United States, as new drugs for chronic illness enable patients, health care providers, and insurers to bypass in-person treatment. Even the wellness industry is cashing in, with spa storefronts and home hydration services.

But while reimbursement for expensive new drugs has drawn the interest of big corporations and private equity, the industry is strained by a lack of nurses and pharmacists. And the less profitable parts of the business — as well as the vulnerable patients they serve — are at serious risk.

This includes the 30,000-plus Americans who rely for survival on parenteral nutrition, which has 72 ingredients. Among those patients are premature infants and post-surgery patients with digestive problems, and people with short or damaged bowels, often the result of genetic defects.

While some specialty infusion drugs are billed through pharmacy benefit managers that typically pay suppliers in a few weeks, medical plans that cover HPN, IV antibiotics, and some other infusion drugs can take 90 days to pay, said Dan Manchise, president of Mann Medical Consultants, a home-care consulting company.

In the 2010s, CVS bought Coram, and Optum bought up smaller home infusion companies, both with the hope that consolidation and scale would offer more negotiating power with insurers and manufacturers, leading to a more stable market. But the level of patient care required was too high for them to make money, industry officials said.

“With the margins seen in the industry,” Manchise said, “if you’ve taken on expensive patients and you don’t get paid, you’re dead.”

In September, CVS announced its purchase of Signify Health, a high-tech company that sends out home-health workers to evaluate billing rates for “high-priority” Medicare Advantage patients, according to an analyst’s report. In other words, as CVS shed one group of patients whose care yields low margins, it was spending $8 billion to seek more profitable ones.

CVS “pivots when necessary,” spokesperson Mike DeAngelis told KHN. “We decided to focus more resources on patients who receive infusion services for specialty medications” that “continue to see sustained growth.” Optum declined to discuss its move, but a spokesperson said the company was “steadfastly committed to serving the needs” of more than 2,000 HPN patients.

DeAngelis said CVS worked with its HPN patients to “seamlessly transition their care” to new companies.

However, several Coram patients interviewed about the transition indicated that it was hardly smooth. Other HPN businesses were strained by the new demand for services, and frightening disruptions occurred.

Smith had to convince her new supplier that she still needed two IV pumps — one for HPN, the other for hydration. Without two, she’d rely partly on “gravity” infusion, in which the IV bag hangs from a pole that must move with the patient, making it impossible for her to keep her job.

“They just blatantly told her they weren’t giving her a pump because it was more expensive, she didn’t need it, and that’s why Coram went out of business,” Smith said.

Many patients who were hospitalized at the time of the switch — several inpatient stays a year are not unusual for HPN patients — had to remain in the hospital until they could find new suppliers. Such hospitalizations typically cost at least $3,000 a day.

“The biggest problem was getting people out of the hospital until other companies had ramped up,” said Dr. David Seres, a professor of medicine at the Institute of Human Nutrition at Columbia University Medical Center. Even over a few days, he said, “there was a lot of emotional hardship and fear over losing long-term relationships.”

To address HPN patients’ nutritional needs, a team of physicians, nurses, and dietitians must work with their supplier, Seres said. The companies conduct weekly bloodwork and adjust the contents of the HPN bags, all under sterile conditions because these patients are at risk of blood infections, which can be grave.

As for Coram, “it’s pretty obvious they had to trim down business that was not making money,” Reddick said, adding that it was noteworthy both Coram and Optum Rx “pivoted the same way to focus on higher-dollar, higher-reimbursement, high-margin populations.”

“I get it, from the business perspective,” Smith said. “At the same time, they left a lot of patients in a not great situation.”)

Smith shares a postage-stamp Queens apartment with her husband, Matt; his enormous flight simulator (he’s an amateur pilot); cabinets and fridges full of medical supplies; and two large, friendly dogs, Caspian and Gretl. On a recent morning, she went about her routine: detaching the bag of milky IV fluid that had pumped all night through a central line implanted in her chest, flushing the line with saline, injecting medications into another saline bag, and then hooking it through a paperback-sized pump into her central line.

Smith has a connective tissue disorder called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which can cause many health problems. As a child, Smith had frequent issues, such as a torn Achilles tendon and shoulder dislocations. In her 20s, while working as an EMT, she developed severe gut blockages and became progressively less able to digest food. In 2017, she went on HPN and takes nothing by mouth except for an occasional sip of liquid or bite of soft food, in hopes of preventing the total atrophy of her intestines. HPN enabled her to commute to George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., where in 2020 she completed a master’s in public health.

On days when she teaches at LaGuardia Community College — she had 35 students this semester — Smith is up at 6 a.m. to tend to her medical care, leaves the house at 9:15 for class, comes home in the afternoon for a bag of IV hydration, then returns for a late afternoon or evening class. In the evening she gets more hydration, then hooks up the HPN bag for the night. On rare occasions she skips the HPN, “but then I regret it,” she said. The next day she’ll have headaches and feel dizzy, sometimes losing her train of thought in class.

Smith describes a “love-hate relationship” with HPN. She hates being dependent on it, the sour smell of the stuff when it spills, and the mountains of unrecyclable garbage from the 120 pounds of supplies couriered to her apartment weekly. She worries about blood clots and infections. She finds the smell of food disconcerting; Matt tries not to cook when she’s home. Other HPN patients speak of sudden cravings for pasta or Frosted Mini-Wheats.

Yet HPN “has given me my life back,” Smith said.

She is a zealous self-caretaker, but some dangers are beyond her control. IV feeding over time is associated with liver damage. The assemblage of HPN bags by compounding pharmacists is risky. If the ingredients aren’t mixed in the right order, they can crystallize and kill a patient, said Seres, Smith’s doctor.

He and other doctors would like to transition patients to food, but this isn’t always possible. Some eventually seek drastic treatments such as bowel lengthening or even transplants of the entire digestive tract.

“When they run out of options, they could die,” said Dr. Ryan Hurt, a Mayo Clinic physician and president of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.

xxx

And then there are the shortages.

In 2017, Hurricane Maria crippled dozens of labs and factories making IV components in Puerto Rico; next came the covid-19 emergency, which shifted vital supplies to gravely ill hospital patients.

Prices for vital HPN ingredients can fluctuate unpredictably as companies making them come and go. For example, in recent years the cost of the sodium acetate used as an electrolyte in a bag of HPN ballooned from $2 to $25, then briefly to $300, said Michael Rigas, a co-founder of the home infusion pharmacy KabaFusion.

“There may be 50 different companies involved in producing everything in an HPN bag,” Rigas said. “They’re all doing their own thing — expanding, contracting, looking for ways to make money.” This leaves patients struggling to deal with various shortages from saline and IV bags to special tubing and vitamins.

“In the last five years I’ve seen more things out of stock or on shortage than the previous 35 years combined,” said Rigas.

The sudden retrenchment of CVS and Optum Rx made things worse. Another, infuriating source of worry: the steady rise of IV spas and concierge services, staffed by moonlighting or burned-out hospital nurses, offering IV vitamins and hydration to well-off people who enjoy the rush of infusions to relieve symptoms of a cold, morning sickness, a hangover, or just a case of the blahs.

In January, infusion professionals urged FDA Commissioner Robert Califf to examine spa and concierge services’ use of IV products as an “emerging contributing factor” to shortages.

The FDA, however, has little authority over IV spas. The Federal Trade Commission has cracked down on some spa operations — for unsubstantiated health claims rather than resource misuse.

Bracha Banayan’s concierge service, called IVDRIPS, started in 2017 in New York City and now employs 90 people, including 60 registered nurses, in four states, she said. They visit about 5,000 patrons each year, providing IV hydration and vitamins in sessions of an hour or two for up to $600 a visit. The goal is “to hydrate and be healthy” with a “boost that makes us feel better,” Banayan said.

Although experts don’t recommend IV hydration outside of medical settings, the market has exploded, Banayan said: “Every med spa is like, ‘We want to bring in IV services.’ Every single paramedic I know is opening an IV center.”

Matt Smith, Elizabeth’s husband, isn’t surprised. Trained as a lawyer, he is a paramedic who trains others at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “You give someone a choice of go up to some rich person’s apartment and start an IV on them, or carry a 500-pound person living in squalor down from their apartment,” he said. “There’s one that’s going to be very hard on your body and one very easy on your body.”

The very existence of IV spa companies can feel like an insult.

“These people are using resources that are literally a matter of life or death to us,” Elizabeth Smith said.

Shortages in HPN supplies have caused serious health problems including organ failure, severe blisters, rashes, and brain damage.

For five months last year, Rylee Cornwell, 18 and living in Spokane, Washington, could rarely procure lipids for her HPN treatment. She grew dizzy or fainted when she tried to stand, so she mostly slept. Eventually she moved to Phoenix, where the Mayo Clinic has many Ehlers-Danlos patients and supplies are easier to access.

Mike Sherels was a University of Minnesota football coach when an allergic reaction caused him to lose most of his intestines. At times he’s had to rely on an ethanol solution that damages the ports on his central line, a potentially deadly problem “since you can only have so many central access sites put into your body during your life,” he said.

When Faith Johnson, a 22-year-old Las Vegas student, was unable to get IV multivitamins, she tried crushing vitamin pills and swallowing the powder, but couldn’t keep the substance down and became malnourished. She has been hospitalized five times this past year.

Dread stalks Matt Smith, who daily fears that Elizabeth will call to say she has a headache, which could mean a minor allergic or viral issue — or a bloodstream infection that will land her in the hospital.

Even more worrying, he said: “What happens if all these companies stop doing it? What is the alternative? I don’t know what the economics of HPN are. All I know is the stuff either comes or it doesn’t.”

Arthur Allen is Kaiser Health News reporter.

More, more, more!

A CVS kiosk set up in Quincy Market, in downtown Boston.

— Photo by Whoisjohngalt

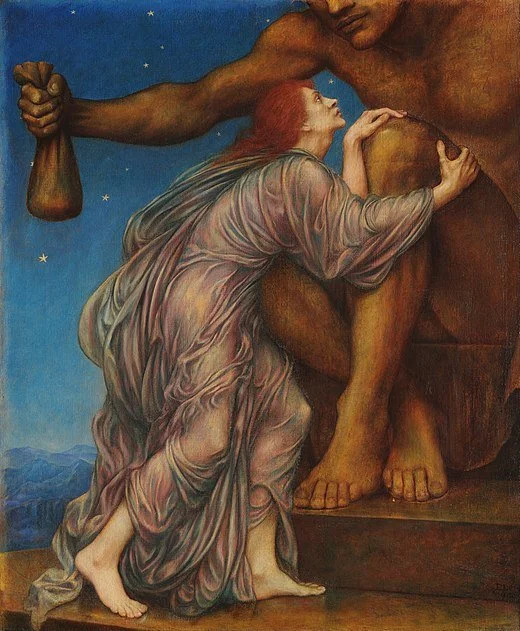

“The Worship of Mammon (1909)’’, by Evelyn De Morgan

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

CVS’s chief executive officer, Karen Lynch, made 458 times the Woonsocket, R.I.-based company’s average employee’s wages in 2021, when her compensation exceeded $20 million while the average CVS worker made $45,010. Cut Ms. Lynch’s taxes some more!

An Economic Policy Institute report in 2021 showed that from 1978 to 2020, the pay of CEO’s of big public companies grew by 1,322 percent, far outstripping stock-market growth as measured by Standard & Poor’s (817 percent). It also exceeded corporate-earnings growth of 341 percent between 1978 and 2019, the latest data available. Meanwhile, compensation of the typical worker grew by just 18 percent from 1978 to 2020.

Where’s the evidence that corporate execs are better these days than they were 40 years ago and thus deserve these gargantuan pay days?

Behind a lot of this extreme compensation is the simple fact that the boards of big companies consist mostly of other very rich corporate execs who serve on multiple boards and give each other huge pay packages with the expectation that they’ll be taken care of in return.

Another is the media creation of the CEO of a big company as a genius superstar worthy of extracting vast sums from the economy.

Of course as they get richer and richer, they get more and more control of the political system, which they use to expand their wealth and power (especially via the GOP/QAnon Party) even further.

Hit these links:

https://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-in-2020/

https://www.golocalprov.com/business/cvss-ceo-lynch-makes-458-times-the-average-cvs-employee

https://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-pay-in-2020/

And:

https://www.salon.com/2022/07/19/just-27-billionaires-spent-90-million-to-buy-congress-report_partner/

https://americansfortaxfairness.org/wp-content/uploads/BBER-FINAL-WITH-LINKS.pdf

And dragging in CVS

Look at the misleading graphics by hitting this link.

It’s not them….

Consumers should be aware of a brazen new scam going around. But then scams breed like flies in the Great Dismal Swamp of the Internet. This one leads off with “Congratulations! A CVSReward has arrived!’’

People are being sent emails that most people would associate with Rhode Island-based CVS Health, the pharmacy chain. It’s all under “CVSReward’’. The emails involve taking a survey for which some (or all?) respondents receive a “free gift” of, say, a watch. The recipients allegedly are only charged for shipping and handling.

But in fact, the recipients are charged for the full price of the watch, from an outfit identified as “Elite Horology,’’ plus of course “shipping and handling’’.

Do CVS, the Federal Trade Commission and other authorities know about this? Is there a security gap at CVS that lets these con men obtain customers’ email addresses?

Elite’s phone:

(phone: 888-534-9649)

Questions/comments on this site: Email rwhitcomb4@cox.net

Rachel Bluth: CVS comes under fire for low nursing-home vaccination rates

CVS store in Coventry, Conn.

— Photo by JJBers

The effort to vaccinate some of the country’s most vulnerable residents against COVID-19 has been slowed by a federal program that sends retail pharmacists into nursing homes — accompanied by layers of bureaucracy and logistical snafus.

As of Jan. 14, more than 4.7 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna covid vaccines had been allocated to the federal pharmacy partnership, which has deputized pharmacy teams from Deerfield, Ill.-based Walgreens and Woonsocket, R.I.-based CVS to vaccinate nursing home residents and workers. Since the program started in some states on Dec. 21, however, they have administered about a quarter of the doses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Across America, some nursing-home directors and health-care officials say the partnership is actually hampering the vaccination process by imposing paperwork and cumbersome corporate policies on facilities that are thinly staffed and reeling from the devastating effects of the coronavirus. They argue that nursing homes are unique medical facilities that would be better served by medical workers who already understand how they operate.

Mississippi’s state health officer, Dr. Thomas Dobbs, said the partnership “has been a fiasco.”

The state has committed 90,000 vaccine doses to the effort, but the pharmacies had administered only 5 percent of those shots as of Jan. 14, Dobbs said. Pharmacy officials told him they’re having trouble finding enough people to staff the program.

Dobbs pointed to neighboring Alabama and Louisiana, which he says are vaccinating long-term care residents at four times the rate of Mississippi.

“We’re getting a lot of angry people because it’s going so slowly, and we’re unhappy too,” he said.

Many of the nursing homes that have successfully vaccinated willing residents and staff members are doing so without federal help.

For instance, Los Angeles Jewish Home, with roughly 1,650 staff members and 1,100 residents on four campuses, started vaccinating Dec. 30. By Jan. 11, the home’s medical staff had administered its 1,640th dose. Even the facility’s chief medical director, Noah Marco, helped vaccinate.

The home is in Los Angeles County, which declined to participate in the CVS/Walgreens program. Instead, it has tasked nursing homes with administering vaccines themselves, and is using only Moderna’s easier-to-handle product, which doesn’t need to be stored at ultracold temperatures, like the Pfizer vaccine. (Both vaccines require two doses to offer full protection, spaced 21 to 28 days apart.)

By contrast, Mariner Health Central, which operates 20 nursing homes in California, is relying on the federal partnership for its homes outside of L.A. County. One of them won’t be getting its first doses until next week.

“It’s been so much worse than anybody expected,” said the chain’s chief medical officer, Dr. Karl Steinberg. “That light at the end of the tunnel is dim.”

Nursing homes have experienced some of the worst outbreaks of the pandemic. Though they house less than 1 percent of the nation’s population, nursing homes have accounted for 37 percent of deaths, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Facilities participating in the federal partnership typically schedule three vaccine clinics over the course of nine to 12 weeks. Ideally, those who are eligible and want a vaccine will get the first dose at the first clinic and the second dose three to four weeks later. The third clinic is considered a makeup day for anyone who missed the others. Before administering the vaccines, the pharmacies require the nursing homes to obtain consent from residents and staffers.

Despite the complaints of a slow rollout, CVS and Walgreens said that they’re on track to finish giving the first doses by Jan. 25, as promised.

“Everything has gone as planned, save for a few instances where we’ve been challenged or had difficulties making contact with long-term care facilities to schedule clinics,” said Joe Goode, a spokesperson for CVS Health.

Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, acknowledged some delays through the partnership, but said that’s to be expected because this kind of effort has never before been attempted.

“There’s a feeling they’ll get up to speed with it and it will be helpful, as health departments are pretty overstretched,” Plescia said.

But any delay puts lives at risk, said Dr. Michael Wasserman, the immediate past president of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine.

“I’m about to go nuclear on this,” he said. “There should never be an excuse about people not getting vaccinated. There’s no excuse for delays.”

Bringing in Vaccinators

Nursing homes are equipped with resources that could have helped the vaccination effort — but often aren’t being used.

Most already work with specialized pharmacists who understand the needs of nursing homes and administer medications and yearly vaccinations. These pharmacists know the patients and their medical histories, and are familiar with the apparatus of nursing homes, said Linda Taetz, chief compliance officer for Mariner Health Central.

“It’s not that they aren’t capable,” Taetz said of the retail pharmacists. “They just aren’t embedded in our buildings.”

If a facility participates in the federal program, it can’t use these or any other pharmacists or staffers to vaccinate, said Nicole Howell, executive director for Ombudsman Services of Contra Costa, Solano and Alameda counties.

But many nursing homes would like the flexibility to do so because they believe it would speed the process, help build trust and get more people to say yes to the vaccine, she said.

Howell pointed to West Virginia, which relied primarily on local, independent pharmacies instead of the federal program to vaccinate its nursing home residents.

The state opted against the partnership largely because CVS/Walgreens would have taken weeks to begin shots and Republican Gov. Jim Justice wanted them to start immediately, said Marty Wright, CEO of the West Virginia Health Care Association, which represents the state’s long-term care facilities.

The bulk of the work is being done by more than 60 pharmacies, giving the state greater control over how the doses were distributed, Wright said. The pharmacies were joined by Walgreens in the second week, he said, though not as part of the federal partnership.

“We had more interest from local pharmacies than facilities we could partner them up with,” Wright said. Preliminary estimates show that more than 80% of residents and 60% of staffers in more than 200 homes got a first dose by the end of December, he said.

Goode from CVS said his company’s participation in the program is being led by its long-term-care division, which has deep experience with nursing homes. He noted that tens of thousands of nursing homes — about 85 percent nationally, according to the CDC — have found that reassuring enough to participate.

“That underscores the trust the long-term care community has in CVS and Walgreens,” he said.

Vaccine recipients don’t pay anything out-of-pocket for the shots. The costs of purchasing and administering them are covered by the federal government and health insurance, which means CVS and Walgreens stand to make a lot of money: Medicare is reimbursing $16.94 for the first shot and $28.39 for the second.

Bureaucratic Delays

Technically, federal law doesn’t require nursing homes to obtain written consent for vaccinations.

But CVS and Walgreens require them to get verbal or written consent from residents or family members, which must be documented on forms supplied by the pharmacies.

Goode said consent hasn’t been an impediment so far, but many people on the ground disagree. The requirements have slowed the process as nursing homes collect paper forms and Medicare numbers from residents, said Tracy Greene Mintz, a social worker who owns Senior Care Training, which trains and deploys social workers in more than 100 facilities around California.

In some cases, social workers have mailed paper consent forms to families and waited to get them back, she said.

“The facilities are busy trying to keep residents alive,” Greene Mintz said. “If you want to get paid from Medicare, do your own paperwork,” she suggested to CVS and Walgreens.

Scheduling has also been a challenge for some nursing homes, partly because people who are actively sick with covid shouldn’t be vaccinated, the CDC advises.

“If something comes up — say, an entire building becomes covid-positive — you don’t want the pharmacists coming because nobody is going to get the vaccine,” said Taetz of Mariner Health.

Both pharmacy companies say they work with facilities to reschedule when necessary. That happened at Windsor Chico Creek Care and Rehabilitation in Chico, Calif., where a clinic was pushed back a day because the facility was awaiting covid test results for residents. Melissa Cabrera, who manages the facility’s infection control, described the process as streamlined and professional.

In Illinois, about 12,000 of the state’s roughly 55,000 nursing home residents had received their first dose by Sunday, mostly through the CVS/Walgreens partnership, said Matt Hartman, executive director of the Illinois Health Care Association.

While Hartman hopes the pharmacies will finish administering the first round by the end of the month, he noted that there’s a lot of “headache” around scheduling the clinics, especially when homes have outbreaks.

“Are we happy that we haven’t gotten through round one and West Virginia is done?” he asked. “Absolutely not.”

Rachel Bluth is a Kaiser Health News correspondent.

Rachel Bluth: rbluth@kff.org, @RachelHBluth

KHN correspondent Rachana Pradhan contributed to this report.

David Warsh: Eating Instagram; McKinsey and OxyContin scandal

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I was as surprised as anyone when a panel of prominent judges earlier this month chose No Filter: The Inside Story of Instagram, by Sara Frier, of Bloomberg News, as the Financial Times and McKinsey Business Book of the Year, so I ordered it. The publisher, Simon & Shuster, was surprised, too: the book has not yet arrived. So I re-read FT staffer Hannah Murphy’s review from last April.

The book sounds absorbing enough: how Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom agreed to sell his start-up for $1 billion over a backyard barbecue at Mark Zuckerberg’s house and then watched in distress as Facebook bent the inventive photography app to purposes of its own. He finally walked away from the company he started, an enterprise that Frier called “a modern cultural phenomenon in an age of perpetual self-broadcasting” brought low by Facebook’s quest for global domination.

FT editor Roula Khalaf praised the book for tackling “two vital issues of our age: how Big Tech treats smaller rivals and how social-media companies are shaping the lives of a new generation.” In a beguiling online profile last summer, Frier explained how “everything changed” for technology reporters covering social media after the 2016 presidential election. Remembering the embrace-extend-extinguish tactics pioneered by Microsoft, antitrust authorities will also want to take a look.

There is, however, a larger issue about the contest itself. Given the temper of the times, I had thought either Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, both of Princeton University, or Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, by Rebecca Henderson, of the Harvard Business School, powerful books of unusual gravity, might capture the blue ribbon. Both specifically criticize a major McKinsey client, Purdue Pharma, and both vigorously reject the market fundamentalism that often has been imputed to the values of the secretive firm in recent decades – “shareholder value” as the only legitimate compass of corporate conduct and all that.

Granted, the prize is said by its sponsors to reward “the most compelling and enjoyable insight into modern business issues” of a given year. Previous panels have interpreted their instructions in a wide variety of ways. A McKinsey executive last year joined the judging panel. I wondered if the other members, none of them strangers to McKinsey’s lofty circles, had successfully argued to include the two critical books on the short list, before selecting a title more narrowly about “modern business issues” to avoid embarrassment to the sponsor. The awarding of literary prizes as it actually works on the inside is sometimes said to be very different from how it may look from the outside.

An OxyContin pill

Whatever the case, the judges could not have known about the news that broke the day before their decision was announced. The New York Times reported that documents released in a federal bankruptcy court had revealed that McKinsey & Co. was the previously unidentified-management consulting firm that has played a key role in driving sales of Purdue’s OxyContin “even as public outrage grew over widespread overdoses” that had already killed hundreds of thousands of Americans.

In 2017, McKinsey partners proposed several options to “turbocharge” sales of Purdue’s addictive painkiller. One was to give distributors rebates of $14,810 for every OxyContin overdose attributed to pills they had sold. Purdue executives embraced the plan, though some expresses reservations. (Read The New York Times story: the McKinsey team’s conduct was abhorrent.) Spokesmen for CVS and Anthem, themselves two of McKinsey’s biggest clients, have denied receiving overdose rebates from Purdue, according to reporters Walt Bogdanich and Michael Forsythe.

Moreover, after Massachusetts’s attorney general sued Purdue, Martin Elling, a senior partner in McKinsey’s North American pharmaceutical practice, wrote to another senior partner, “It probably makes sense to have a quick conversation with the risk committee to see if we should be doing anything” other than “eliminating all our documents and emails. Suspect not but as things get tougher there someone might turn to us.” Came the reply: “Thanks for the heads-up. Will do.” Elling has apparently relocated his practice from New Jersey to McKinsey’s Bangkok office, The Times’s reporters write.

Last week The Times reported that McKinsey & Co. issued an unusual apology for its role in OxyContin sales and vowed a full internal review. Sen. Josh Hawley (R.- Mo.) wrote the firm asking if documents had been destroyed. “You should not expect this to be the last time McKinsey’s work is referenced,” the firm wrote in an internal memo to employees. “While we can’t change the past we can learn from it.”

Another rethink is for the FT. The newspaper started its award in 2005, with Goldman Sachs as its co-sponsor. Tarnished by the 2008 financial crisis and the aftermath, the financial-services giant bowed out after 2013 and McKinsey took over. The enormous consulting firm is famous mainly for the anonymity on which it insists, but the Purdue Pharma scandal isn’t the first time that McKinsey has been in the news recently, especially for its engagements abroad, in Puerto Rico and Saudi Arabia. A thorough audit of its practices, reinforced by outside institutions, is overdue. In an age of mixed economies and transparency, McKinsey’s business model of mutually-contracted secrecy between the firm and the client seems outdated

Why the need for sponsorship? It would seem to be mainly a form of cooperative advertising. The cash awards to authors are lavish: £30,000 to the winner, £10,000 to each of five finalists, undisclosed sums to the judges, publicists and for advertising. That makes McKinsey’s investment a spectacular bargain, but it is something of a poisoned chalice for the FT.

The prize’s reputation as recognizing entertaining writing about important business topics is well established. Why not dispense with the money and influence? Who knows what McKinsey does and for whom? Isn’t trustworthy filtering of information the very essence of the newspaper’s business?

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this piece first ran.

Phil Galewitz: Long, long delays in getting COVID-19 test results from CVS, etc.

Elliot Truslow went to a CVS drugstore on June 15 in Tucson, Arizona, to get tested for the coronavirus. The drive-thru nasal swab test took less than 15 minutes. (CVS is based in Woonsocket, R.I.)

More than 22 days later, the University of Arizona graduate student was still waiting for results.

Elliot Truslow had a drive-thru COVID test at a CVS in Tucson, Arizona, on June 15. CVS told Truslow to expect results in two to four days, but 22 days later, still nothing.

Truslow was initially told it would take two to four days. Then CVS said five or six days. On the sixth day, the pharmacy estimated it would take 10 days.

“This is outrageous,” said Truslow, 30, who has been quarantining at home since attending a large rally at the school to demonstrate support of Black Lives Matter. Truslow has never had any symptoms. At this point, the test findings hardly matter anymore.

Truslow’s experience is an extreme example of the growing and often excruciating waits for COVID-19 test results in the United States.

While hospital patients can get the findings back within a day, people getting tested at urgent care centers, community health centers, pharmacies and government-run drive-thru or walk-up sites are often waiting a week or more. In the spring, it was generally three or four days.

The problems mean patients and their physicians don’t have information necessary to know whether to change their behavior. Health experts advise people to act as if they have COVID-19 while waiting — meaning to self-quarantine and limit exposure to others. But they acknowledge that’s not realistic if people have to wait a week or more.

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who announced Monday that she had tested positive for the virus, complained she waited eight days for her results in an interview on MSNBC Wednesday. During that time, she held a number of meetings with city officials and constituents — “things that I personally would have done differently had I known there was a positive test result in my house,” she said on “Morning Joe.”

“We’ve been testing for months now in America,” she added. “The fact that we can’t quickly get results back so that other people are not unintentionally exposed is the reason we are continuing in this spiral with COVID-19.”

The slow turnaround for results could also delay students’ return to school campuses this fall. It’s already keeping some professional baseball teams from training for a late July start of the season. The lag times could even foil Hawaii’s plan to welcome more tourists. The state had been requiring visitors to quarantine for 14 days, but it announced last month that starting Aug. 1 that mandate would be lifted for people who could show they tested negative within three days before arriving in the islands.

In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom noted the problem when addressing reporters Wednesday. “We were really making progress as a nation, not just as a state, and now you’re starting to see, because of backlogs with [the lab company] Quest and others, that we’re experiencing multiday delays,” he said.

The delays even apply to people in high-risk, vulnerable populations, he said, citing a massive outbreak at San Quentin State Prison, which has been sending its tests to Quest. The state is now looking at partnering with local labs, hoping they can provide faster turnaround.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious disease expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, said the long waits spell trouble for individuals and complicate the national response to the pandemic.

“It defeats the usefulness of the test,” he said. “We need to find a way to make testing more robust so people can function and know if they can resume normal activities or go back to work.”

The problem is that labs running the tests are overwhelmed as demand has soared in the past month.

Azza Altiraifi of Vienna, Virginia, got her COVID test at CVS on July 1. She still has symptoms, including fatigue — but as of July 7, she was still awaiting the result.

“We recognize that these test results contain actionable information necessary to guide treatment and inform public health efforts,” said Julie Khani, president of the American Clinical Laboratory Association, a trade group. “As laboratories respond to unprecedented spikes in demand for testing, we recognize our continued responsibility to deliver accurate and reliable results as quickly as possible.”

Dr. Temple Robinson, CEO of Bond Community Health Center in Tallahassee, Florida, said test results have gone from a three-day turnaround to 10 days in the past several weeks. Many poor patients don’t have the ability to easily isolate from others because they live in smaller homes with other people. “People are trying to play by the rules, but you are not giving them the tools to help them if they do not know if they tested positive or negative,” she said.

“If we are not getting people results for at least seven or eight days, it’s an exercise in futility because either people are much worse or they are better” by then, she said.

Given the lag in testing results from big lab companies, Robinson said her health center this month bought a rapid test machine. She held off buying the machine due to concerns the tests produced a high number of false-negative results but went ahead earlier this month in order to curtail the long waits, she said.

Robinson doesn’t blame the large labs and points instead to the surge in testing. “We are all drinking through a firehose, and none of the labs was prepared for this volume of testing,” she said. “It’s a very scary time.”

Azza Altiraifi, 26, of Vienna, Virginia, knows that all too well. She started feeling sick with respiratory symptoms and had trouble breathing on June 28. Within a few days she had chills, aches and joint pain and then a needling sensation in her feet. She went to her local CVS to get tested on July 1. She was still awaiting the result July 8.

What is most frustrating about her situation is that her husband is a paramedic, and his employer won’t let him work because he may have been exposed to the virus. He was tested July 6 and is still awaiting news.

“This is completely absurd,” Altiraifi said. She also worries that her husband may have unknowingly passed on the virus on one of his ambulance calls to nursing homes and other care facilities before he began isolating at home. He has not shown any symptoms.

Altiraifi, who still has symptoms including fatigue, said she was initially told she would have results in two to four days, but she was suspicious because after using a nasal swab to give herself the test, the box to put it in was so full it was hard to close.

Charlie Rice-Minoso, a spokesperson for CVS Health, said patients are waiting five to seven days on average for test results. “As demand for tests has increased, we’ve seen test result turnaround times vary due to temporary processing capacity limitations with our lab partners, which they are working to address,” he said.

In South Florida, the Health Care District of Palm Beach County, which has tested tens of thousands of patients since March, said findings are taking seven to nine days, several days longer than in the spring.

CityMD, a large urgent care chain in the New York City area, said it now tells patients they will likely wait at least seven days for results because of delays at Quest Diagnostics.

Quest Diagnostics, one of the largest lab companies in the United States, said average turnaround time has increased from three to five days to four to six days in the past two weeks. The company has performed nearly 7 million COVID tests this year.

“Quest is doing everything it can to add testing capacity to reduce turnaround times for patients and providers amid this crisis and the unprecedented demands it places on lab providers,” said spokesperson Kimberly Gorode.

At Treasure Coast Community Health in Vero Beach, Florida, officials are advising patients of a 10- to 12-day wait for results.

CEO Vicki Soule said Treasure Coast is deluged with calls every day from patients wanting to know where their test results are.

“The anxiety on the calls is way up,” she said.

Julie Hall, 48, of Chantilly, Virginia, got tested June 27 at an urgent care center after learning that her husband had tested positive for COVID-19 as he prepared for hip replacement surgery. She was dismayed to have to wait until July 3 to get an answer.

“I was thrilled to be negative, but by that point it likely did not matter,” she said, noting that neither she nor her husband, Chris, showed any symptoms.

“It was awful and terrible because of the unknowns and not knowing if you exposed someone else,” she said of being quarantined at home awaiting results. “Whenever you would sneeze, someone would say ‘COVID’ even though you feel completely fine.”

Senior correspondent Anna Maria Barry-Jester in California contributed to this article.

Phil Galewitz is a reporter for Kaiser Health News.

Phil Galewitz: pgalewitz@kff.org, @philgalewitz

CVS may be a leader in health-care transformation

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Woonsocket-based CVS’s purchase of Aetna, the huge insurance company, could at least start to make fragmented and exorbitantly expensive U.S. health care a bit more coherent as well as cutting costs for consumers, both in medical-visit bills and insurance premiums. (We’ll see if that happens in our profit-obsessed system.)

Of course, other pharmacy chains and insurers will also tie the knot.

By putting together the insurance function and the direct provision of care, the merger will help create better, more complete patient medical records, thus facilitating better, especially preventive, care. And by helping to make many CVS drugstores even more of the primary-care/preventive-care centers that they’ve been becoming the past few years, the merger should take the pressure off astronomically expensive hospital emergency rooms, whose overuse is one reason that America’s health-care system is so expensive and inefficient.

Much of the treatment in CVS’s Minute Clinics is provided by nurse practitioners and physician assistants, who are less expensive than U.S. physicians -- the world’s highest paid. The American Medical Association has opposed the merger in part because it fears that the competition will cut doctors’ pay.

Importantly, the merger will strengthen CVS in negotiating with drug makers, which, protected by massive lobbying operations in Washington, charge by far the highest prices in the world – indeed sometimes engage in price-gouging. Those prices are yet another reason why health-care costs threaten to bankrupt the country.

(Happily, Trump signed two bipartisan bills into law last week to ban so-called gag clauses at the pharmacy counter. The bills, the Patient Right to Know Act and the Know the Lowest Price Act, would let pharmacists tell patients that they could save money by paying cash for drugs or try a lower-cost alternative. The existence of gag clauses was an outrage.)

We won’t know for several years what the full effects of the CVS-Aetna merger will be but it’s obvious that this experiment could profoundly affect many millions of Americans.

Will consumers benefit, as well as CVS senior executives and other shareholders?

Health-care hurricane

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

As insurers, drugstore chains, such as Rhode Island-based CVS, with its Minute Clinics, and the likes of Walmart team up to provide direct health care, independent physician groups face growing pressure. Many doctors have decided to throw in the towel and become hospital employees. Meanwhile, many physician groups (including the one I use) are extending their hours and making other changes to be more convenient for harried patients in order to better compete with the retail clinics.

The clinics are a response to America’s astronomically expensive, fragmented and inefficient health-care system. They offer a range of services for injuries and illnesses that can often be treated by a nurse, nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant at a cost considerably less than a physician would charge and much, much less than a hospital emergency room.

But will your local Minute Clinic get to know you, especially if you have a chronic illness, as well as your primary-care doctor, so as to be in a position to adjust your care over time? And what sort of relationships will develop between local physicians and retail clinics, considering that they’ll often be competitors? The retail health-care revolution is just getting going. The old model of American health care is falling apart; it’s economically unsustainable.

Aetna CEO touts return to community-based healthcare

Via Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com)

FierceHealthcare reports that Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini “is pushing for a return to community-based healthcare even as the insurance company prepares to merge with retail pharmacy giant CVS.''

“Critics of the merger have said the deal will hurt competition and cut local services. But Bertolini said the $69 billion deal with CVS doesn’t change the fact that the healthcare industry is moving toward a renaissance of community-based care,” the news service reported.

“Everything is going back to community,” Bertolini said at a conference in California. “I think the best way to manage the kind of shift we’re in is to go back to community and build smaller and smaller governance models to help support the growth of this. What you’re in essence building is a marketplace in the community around health.” Aetna is based in Hartford and CVS in Woonsocket, R.I.

To read more, please hit this link.

Calif. to probe Aetna's coverage denials.

The Aetna headquarters building, in Hartford, designed by renowned architect James Gamble Rogers, is the world's largest Colonial Revival Building. It was finished in 1931.

By BARBARA FEDER OSTROV

Both of California’s health insurance regulators said they will investigate how Aetna Inc. makes coverage decisions, as the lawsuit of a California man who is suing the nation’s third-largest insurer for improper denial of care heads for opening arguments on Wednesday. Woonsocket, R.I.-based CVS Health, the pharmacy giant, seeks to buy Aetna.

The Department of Managed Health Care, which regulates the vast majority of health plans in California, said Monday it will investigate Hartford, Conn.-based Aetna after CNN first reported Sunday that one of the company’s medical directors had testified in a deposition related to the lawsuit that he did not examine patients’ records before deciding whether to deny or approve care. Rather, he relied on information provided by nurses who reviewed the records — and that was how he was trained by the company, he said.

Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones had already told CNN his office would investigate Aetna, which he reconfirmed in a statement Monday.

“If a health insurer is making decisions to deny coverage without a physician ever reviewing medical records, that is a significant concern and could be a violation of the law,” Jones said.

It is unclear how widespread the review of patient claims by non-physicians is in the industry or whether other insurers will feel compelled to revisit their practices.

The California Department of Insurance, which Jones heads, regulates only a small fraction of the state’s health plans, but they include several Aetna policies. He has previously criticized Aetna for “excessive” health insurance rate hikes, though neither his agency nor the managed health care department has the power to stop the increases.

Jones’ investigation of Aetna will review denials of coverage or pre-authorizations during the tenure of the medical director who testified in the California lawsuit, Jay Ken Iinuma, who has since left the company. Insurance department investigators will also look into Aetna’s procedures for managing medical coverage decisions generally.

The dual investigations come as federal regulators are examining a planned $69 billion purchase of Aetna by pharmaceutical giant CVS — a deal that many experts believe could transform the health care industry.

It’s unclear how the investigations might affect Aetna’s future coverage decisions, or those of other insurers, said Shana Alex Charles, an insurance industry expert and assistant professor at California State University-Fullerton. But she praised the decision to investigate as exactly what insurance regulators should be doing. “Without that strict oversight, corners get cut,” Charles said.

Scott Glovsky, the lawyer representing the California plaintiff, Gillen Washington, said he and his client were “very pleased” by the news that Aetna will be investigated. Speaking Monday, before the managed care department said it would also investigate, Glovsky said his client brought the case “to stop these illegal practices, and we’re looking forward to the insurance commissioner’s investigation so we can make things safer for Aetna patients.”

Washington, of Huntington Beach, had been receiving expensive medication for years to treat a rare immune system disorder known as Common Variable Immune Deficiency.

But in 2014, Aetna denied the college student’s monthly dose of immunoglobulin replacement therapy, saying his bloodwork was outdated. During the appeal process, Washington developed pneumonia and was hospitalized for a collapsed lung.

In recent years, as California Healthline reported last June, patients with similar diseases have faced increasing difficulty getting their insurers to approve treatments, according to clinicians and patient advocates.

In an e-mailed statement on Monday, Aetna did not directly address the question of case reviews by non-physicians. It said its “medical directors review all necessary available medical information for cases that they are asked to evaluate. That is how they are trained, as physicians and as Aetna employees.” It added, “adherence to those guidelines, which are based on health outcomes and not financial considerations, is an integral part of their yearly review process.”

Aetna also noted that it has paid for all of Washington’s treatments since 2014 and continues to do so.

Aetna said in previous documents filed in the lawsuit that it is standard for people with Washington’s immunodeficiency disease to get regular blood tests and that Washington had failed to do so. But Washington’s attorney said his client clearly needed the medication and that Aetna’s action violated its contract with Washington.

Charles, the professor, said she was most surprised by the fact that Iinuma had admitted not only that he hadn’t reviewed Washington’s medical records personally, but that he had no experience treating his disease. The burden should be on insurers to demonstrate why treatment should be stopped, not on doctors and patients to show why it should be continued, Charles said.

“It’s easy to see the cases as just files and not people standing in front of you,” she said.

CVS-Aetna merger: Who would benefit besides top execs and other shareholders?

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

Besides senior executives and other Aetna shareholders, who would benefit most from CVS’s $69 billion acquisition of Aetna?

Well, the new behemoth’s pharmacy benefit management operation might use its even greater bargaining power with drug makers to negotiate down the extreme, indeed extortive, cost of so many prescription drugs in such a way as to benefit consumers. But I doubt it. It’s more likely that they’ll keep the savings to benefit CVS-Aetna senior executives and other shareholders and consumers will see little if any benefit from that.

Indeed, if the merger drives competitors out of business, CVS might, in the fullness of time and pricing power, increase other prices for its captive customer base a lot. But with giant insurer UnitedHealth Group also getting into the big-time clinic business, too, maybe that might not happen.

Anyway, much good can come from this combination.

The merger is part of CVS’s plan to turn itself into a much-wider-service health-care provider, building on its rapidly expanding chain of Minute Clinics. There, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and regular nurses are joining with pharmacists to offer many services that you’d once have to go to a doctor’s office or hospital to get, at very high cost. After all, U.S. physicians are highest paid in the world, co-payments are jumping, etc. A brief visit to a hospital emergency room shows that far too many patients go to that very expensive venue for problems that could better be addressed in a, well, Minute Clinic. The aging of the population, and thus a flood of sicker people, especially raises the potential of Minute Clinic-like health-care retailers to slow surging health-care costs, or some of them anyway.

Indeed, whatever happens with drug prices at the likes of CVS-Aetna, consumers can save time, and thus money, by using a facility that will offer many primary-care services beyond pills, such as medical tests, physical exams and medical consultations, as well as food and other products. Life can be frantic. One-stop shopping is very attractive. At the least, these centers might help you cut down on transportation costs.

Getting your health insurance from the same organization where you get much of your health care may also make your life easier. For one thing, the sharing of patient data between the insurance side and the provider (CVS) may facilitate better care, especially for those with such chronic ailments as heart disease. But, yes, it will also make your personal data more vulnerable to computer hacking from crooks domestic or foreign (especially the Russians and Chinese)….

But again, much depends on whether the merger ends up squashing CVS-Atena competitors so much that the behemoth can jack up prices, including for insurance. Many patients may find themselves trapped in expensive “health-care hubs.’’ Always remember that most companies care far more about their senior executives and other shareholders than anyone else.

And the CVS-Aetna deal is more bad news for hospitals and physician groups: The new entity will probably drain away many of their patients.

Unless executives of the new outfit decide they really want the glamour of a big city headquarters and move it to, say, New York or Boston (remember Fleet Financial Group leaving Providence for Boston?), the merger is good news for Rhode Island, both psychologically (having such an even bigger company based here) and in the new employees that CVS-Aetna would presumably need to hire here for additional administrative, marketing and other headquarters-related work.

But don’t bet the farm on CVS keeping its headquarters in Woonsocket. Increasingly, those working at corporate headquarters, especially younger up-and-coming employees, and the executive suite, like to be in a dynamic city instead of some suburban-style office park.

So Providence’s Financial District, once an important banking center, might eventually host CVS-Aetna headquarters. Given that Aetna is a financial company that would be fitting. And the Rhode Island School of Design’s army of graphic and other designers would be next door; a few blocks away would be the Brown Medical School. Both very handy for a consumer health-care chain. There’s been chatter lately that toy-and-entertainment giant Hasbro might consider moving its headquarters to downtown Providence. Wouldn't it be nice if this old city once again became a major corporate headquarters town?

Llewellyn King: Be scared of whom you kiss, and other big changes in 2017

"The Mistletoe Seller,'' by Adrien Barrère

Some years are indelibly etched into history, like 1941, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor; 1964, with the Civil Rights Act; and 1968, with the anti-war demonstrations.

Such a year may be 2017, not only because of Donald Trump’s presidency but also because of revolutionary changes in the way we live and work that aren’t directly produced or ratified by politics.

Here are some of the takeaways:

The uprising of women against men in power who have harassed them, assaulted them and sometimes raped them. Nothing quite like this has happened since women got the vote. The victims have already wrought massive changes in cinema, journalism and Congress: Great men have fallen, and fallen hard. Can the titans of Wall Street and the ogres of the C-Suite be far behind?

This Christmas, more people will buy online than ever before. Delivery systems will be stretched, from the U.S. Postal Service to FedEx, which is why Amazon and others are looking at new ways of getting stuff to you. There will be bottlenecks: Goods don’t come by wire, yet. The old way is not geared for the new.

The sedan car — the basic automobile that has been with us since an engine was bolted in a carriage — is in retreat. Incredibly, the great top-end manufacturers, from Porsche to Rolls Royce and even Lamborghini, are offering SUVs. They win for rugged feel, headroom and, with all-wheel drive, they’ll plow through snow and mud. In the West, luxury pickups are claiming more drivers every year for the same reasons.

No longer are electric vehicles going to be for the gung-ho few environmentalists. Even as the big automakers are gearing up for more SUV production, they’re tooling up for electrification on a grand scale, although the pace of that is uncertain. Stung by the success of Tesla, the all-electric play, General Motors is hoping to get out in front: It is building on its all-electric Volt. Volvo is going all-electric and others want to hedge the SUV bet. The impediments: the speed of battery development and new user-friendly charging.

The money we have known may not be the money we are going to know going forward. In currency circles, there is revolution going on about a technology called “blockchain.” Its advocates, like Perianne Boring, founder and president of the Chamber of Digital Commerce, believe it will usher in a new kind of currency that is safe and transparent. A few are making fortunes out of bitcoin, which has risen 1,000 percent in value this year so far. A fistful of new currencies are offered — and even bankrupt Venezuela is trying to change its luck with cryptocurrency. For those in the know, blockchain is the new gold. Will it glitter?

The proposed merger between CVS, a drugstore chain, and Aetna, an insurance giant, may be one of the few mergers that might really benefit the consumer as well as the stockholders and managers. It will lower drug prices because both the drug retailer and the paymaster will be at the same counter. Expect this new kind of health provider to drive hospital charges toward standardization.

This holiday season, consider the changes in the way you live now. Watch out for whom and how you kiss under the mistletoe, and for how Internet purchases get to you. If a new car is in store for you in 2018, a difficult choice may be to venture electric, go SUV or stay with a sleek sedan. And will you pay for it with the old currency or the new-fangled cryptocurrency?

Happy holidays!

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King (llewellynking1) is executive producer and host ofWhite House Chronicle, on PBS.

The Tesla Model 3 first deliveries event took place on July 28, 2017.

Robert Whitcomb: In the Amazon jungle

Amazon is an impressive if rather creepy company, with its style set by its cold, “data-driven’’ founder/CEO, Jeff Bezos. An Aug. 15 New York Times piece, “Inside Amazon,’’ laid out the travails of the monopolistic and Darwinian enterprise’s white-collar workforce. Their issues have gotten more attention than the much worse Dickensian conditions of the blue-collar employees in its warehouses and the company’s relentless accumulation, like the also Orwellian Google’s, of our personal information. Amazonianism’s causes?

One is in the mirror. Americans have grown addicted to buying stuff online -- of course, the cheaper the better. They seem to want to avoid face-to-face interactions in stores -- and community engagement in general -- and Amazon’s power ensures that they’ll get low prices, at least for now (see below), even as their local stores close because of such online competition.

The preference for communicating via screens rather than person-to-person is especially common among the young, who grew up in the Internet Age. Human-resource managers have told me that young job applicants often don’t look them in the eye because in-person encounters make them anxious.

The disappearance of many well-paying jobs, and static (or worse) compensation except for top executives and investors, have encouraged consumers to seek out cheaper stuff than a few decades ago. But – irony of ironies! – Amazon and other high-tech automators have helped destroy good U.S. jobs in their “data-driven’’ mania to take full advantage of the international low-wage, cheap-goods machine.

Physical-store chains such as CVS and Home Depot are doing their bit to kill jobs --- by, for instance, installing automatic checkouts. I try to boycott stores with these machines because I know that each means the loss of another entry-level or second job for someone who needs it. This makes me feel better for a few minutes.

If Amazon’s workplace brutalities offend some consumers, they could resume shopping in their own communities and thus help employ some of their neighbors. Most won’t.

And look to Washington, where ideology and campaign contributions ensure that the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division doesn’t go after such monopolies as Amazon and Google. Until about 1980, Republican and Democratic administrations actually enforced laws against monopoly. The long disinclination to do so will hit consumers hard when Amazon, which has been undercutting other retailers to gain maximum market share, killing many brick-and-mortar competitors, suddenly jacks up prices big time.

Also consider the collapse of the private-sector union movement. If there were unions at Amazon, the Third World work environment would quickly go away. Gilded Age working conditions helped spawn the union movement in the first place. Now, management’s utter dominance has employees ready to put up with anything to keep their jobs.

Meanwhile, the “Big Data’’ revolution is turning workers into organic robots, soon to be replaced by real, inorganic robots. When every move of workers is measured for maximum productivity and profit potential, as at Amazon, kindly treatment of employees pretty much disappears. Employees are mere data points.

This process started with assembly-line and other blue-collar workers. The generally affluent types who read, say, The New York Times didn’t care that much. But turning employees into metrics is now heading rapidly up the food chain. Physicians, lawyers, tech engineers, middle managers and journalists (monitored for the number of Internet clicks their work gets) are being measured daily by senior executives who see their employees as entirely fungible and disposable.

And don’t expect the executive suite to share the riches from this speed-up with lower-level employees. The tendency for more and more of the wealth of companies to be shared by fewer and fewer people continues apace. We’re on a selfishness wave.

Amazon has created a fascinating machine for distributing goods. (Its delivery drones are next -- maybe equipped with surveillance gear?) Mike Daisey, writing in The Guardian (“Amazon’s brutal work culture will stay: bottom lines matter more than people,’’ Aug. 22), quoted comedian Louis C.K. as saying about such enterprises that “everything’s amazing and nobody’s happy’’ . Well, some are.

Anyway, most Americans seem to adore Amazon, which will repay them good and hard.

xxx

Lovely dim late-summer light today, and leaves are falling off the plane trees from sheer exhaustion.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is a Providence-based editor and writer, a partner at Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com) and a Fellow of the Pell Center, in Newport, He used to be the editorial-page editor of The Providence Journal, the finance editor of the International Herald Tribune and an editor at The Wall Street Journal, among other jobs.

Of class and charity

By ROBERT WHITCOMB

Philanthropic contributions by very rich people get a lot of attention. An example around here is Thomas Ryan, a former head of CVS who recently gave $15 million to the University of Rhode Island for a brain-science center to be named after his parents.

Besides the satisfactions of giving per se and the plaudits of the general public, gifts are sometimes meant to show other rich people how successful the givers are. This explains why so much new money rushes into already very rich “nonprofit” institutions, such as Ivy League colleges and big art museums. Wouldn’t giving a pile to, say, a community college serving poor people do more for society than adding yet more to Harvard’s $31 billion endowment?

And this is not the age of the anonymous contribution. Of course, nonprofits, besides appealing to altruism and ego, know that publicizing the names of the donors may encourage an arms race of giving by other rich people.

Anyway, URI alumnus Ryan commendably gave to a local and grossly underfunded public institution. A few years back, the arena at URI was named after him as a result of gifts by him and CVS. In his last 14 months as CEO, he made $124 million, reported Dow Jones. Of course, if the very rich paid a tad more in taxes, then public institutions could more often build such public facilities out of public money and not always be selling “naming opportunities.”

Large public companies’ senior execs have rarely been romantic altruists. But there’s no doubt that they have adjusted their missions, and sense of civic duty, in the past 30 or so years via tax and other legal changes engineered by their lobbyists.

Most of these companies used to consider themselves as having a fairly wide range of stakeholders — not just senior executives and other big shareholders but nonexecutive employees and the communities within which the companies operated. The idea was that the long-term success of the companies would depend on addressing the welfare of all constituencies.

Now the aim above all is to maximize and speed compensation for senior execs, on which, because of lobbyists’ success in creating tax dodges, many pay remarkably little tax, considering their wealth. Investment gains via stock options, etc., are much tax-favored over wages. (The quickest way to maximize their personal profits is to lay off and/or cut the compensation of lower-level employees.) This explains in part, along with globalization, computerization, automation and the loss of local ownership in many places — laying off your neighbors is tough — explains some of the woes of the middle class the past 30 years or so.

Then there’s American feudalism. The Walton family has a fortune of about $100 billion. They have so much money, in part, because their company pays their employees so little. Some Walmart stores have food drives for impoverished Walmart employees.

The holders of current and future dynastic wealth arrange through tricky trusts (including the creative use of charities) and other perfectly legal mechanisms to pay remarkably little or no estate or gift taxes and thus help ensure the self-perpetuation of power and wealth for their heirs. Readers should read about the wonders of “donor-advised funds” for charities — also a cash cow for financial firms because of the fees — and “charitable lead annuity trusts,” used to boost dynastic wealth by avoiding taxes.

The usual structure for these things is the "foundation,'' which can sometimes be more of creature for perpetuating private dynastic wealth and power than a device for good works.

Some more reasons that the government is broke.

Among other benefits, this dynastic wealth gives favored families access to the fanciest schools with the best-connected faculty and students, which, in turn, reinforces the vast advantage that the lucky heirs already have. Thus there’s less social mobility in America than in most of its developed world competitors.

The public might want to at least consider whether society would be better off if the very rich shared a tad more of their wealth further upstream rather than through the charities they create to do good works, glorify their names and/or avoid paying taxes that pay for public services such as URI.

***

A good thing about this sometimes gray, sometimes golden time of the year is that you don’t have to weed for a while and it cleans out the mosquitoes. No wonder farmers tend to like November and December. They get a rest. Too bad the holidays have to ruin it.

***