David Warsh: We should pay more attention to this outfit

1050 Massachusetts Ave. in Cambridge, where the National Bureau of Economic Research is based.

— Photo by Astrophobe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

An interesting fact: The leaders of Harvard University, Stanford University, Brown University and the University of California at Berkeley have something in common. Alan Garber, Jonathan Levin, Christina Paxson and Richard Lyons are all research associates of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Four out of 17,000+ NBER researchers, the preponderance of them economists, is not a large portion of the whole. But it may offer a hint of what top universities are looking for in their presidents.

The NBER is an unusual organization. Founded in 1920 by two individuals of very different outlooks, an executive of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company and a socialist labor organizer with a PhD from Columbia. Their idea was to fund independent studies of issues about which widespread differences of opinion existed: changes in the gap between rich and poor during the Gilded Age and the Progressive era, as well as the effects of large-scale immigration on wages. National income and its distribution have been the core of NBER studies ever since, along withe the structure of business cycles, too.

Since the 1970s, though, when its headquarters moved from New York City to Cambridge, Mass., and decentralized its research, a host of new topics have come under the NBER microscopes. Everything from the economics of health insurance and childhood education to inflation and national defense practices are investigated with imaginative theory, data, and statistical technique.

A look at the governance of the organization discloses the key to its success over a hundred years. Three classes of directors keep their eyes on the organization’s pursuits: a diverse collection of outsiders; a class of representatives of universities; and another of professional associations of one sort and another.

As in the days of its founding, the NBER seeks to bridge gaps between antagonistic factions. Its culture is suffused with respect for differences of opinion. Its goal is building consensus.

Would those characteristics be attractive to universities eager to get themselves off the front pages of newspapers?

Of course they would. A little more attention in those newspapers to NBER findings might help as well.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based Economic Principals.

David Warsh: What George W. Bush did right

Federal Reserve System headquarters, in Washington, D.C.

— Photo by DestinationFearFan

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Before my column, called Economic Principals, goes monthly, I want to revisit what now seems to be its single most important misjudgment in forty years. While it occurred fifteen years ago, it has relevance to the present day.

The Jan, 25, 2009, edition of the weekly, “In Which George W. Bush Enters History,” I began:

George W. Bush left Washington last week amid a hail of jeers. “The Frat Boy Ships Out” headlined The Economist. “Serially incompetent,” declared the Financial Times. “Worse than Hoover,” concluded Columbia University historian Alan Brinkley.

Bush arrived in Midland, Texas, to find a cheering crowd of 20,000.

I was a little more temperate. Bush’s admirers for years had for years portrayed him as resembling Harry Truman – unpopular when leaving office, later remembered with “a tincture of admiration and regret.” A more re-illuminating comparison, I suggested, citing expert opinion, was to Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), the last president with a faith-based foreign policy.

I said nothing about the apartheid policy that Wilson, a Virginian, reinstalled; this was before the Third Reconstruction gathered steam, George Floyd (1973-2020) and The New York Times’s 1619 project. It was a pretty good column, worth reading today, emblematic of the weekly’s style, before, a year later, I began writing the book that has preoccupied me ever since.

Wilson’s case is a good illustration of the fact that every president makes so many decisions about so many polices that it is difficult, if not impossible to single out in his day the one for which he’ll be remembered decades later, depending on the decade. Bush’s great achievement grew out of two decisions he made during the final quarter of his administration.

The second half had started badly enough with his Second Inaugural Address.

[I]t is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.

Then came the Hurricane Katrina flood, the plan to privatize Social Security, the two-thousandth American death in Iraq, Vice president Dick Cheney shooting a fellow fowler during a Texas partridge hunt. An old friend dates the low point as Bush’ s attempt to appoint one of his staffers to the Supreme Court.

After that, things improved. After heavy losses in the mid-term election, Bush fired Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, turned away from Cheney in favor of Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. He appointed corporate attorney and former appellate court judge John Roberts to the Supreme Court. A year later he picked Goldman Sachs chief executive Henry Paulson as Treasury secretary.

Most important, in October 2005, Bush chose Ben Bernanke an expert on the Great Depression, to be chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Bernanke, a former Princeton University professor, had spent four years of his administration as a governor of the Federal Reserve Board, then two as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. The joke at the time was that Bush chose Bernanke because he wore white socks with his dark suits to White House briefings.

Bernanke had a relatively peaceful first year as chairman, but by 2007 was preparing measures behind the scenes to defuse or at least contro a slowly building crisis. By the summer of 2008, the banking system was on the verge of collapse. Even after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, in September, Paulson continued to argue that a combination of lending and takeovers by a consortium of big banks could resolve it. Bernanke and Timothy Geithner, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, said no. After three days, Paulson folded his hand. Government lending to stop the crisis would be required. A day of meetings with legislators followed.

And on that Friday Bush made his second crucial decision. He walked out with the others to the Rose Garden to make an out-of-the blue plea for a something called a Troubled Asset Relief Program. Nobody seemed to know quite what it might do. Never mind that five weeks of negotiation were required to clarify the matter. By October the panic had been quelled. Last-minute lending by the Fed Reserve, backstopped by the U.S. Treasury, and ten other central banks around the world, had prevented what otherwise virtually certainly would have turned into a second Great Depression had a lawsuits race to the bottom begun.

Bush got little credit for his courage. Barack Obama defeated John McCain in November and attention quickly shifted to blame, and the steep recession that had already begun. Unemployment climbed to 10 percent, not the twenty or more that had been feared in those five desperate weeks. Ahead lay Obamacare and the Tea Party.

Like the rest of the press, I mostly missed the story at the time. Bush’s admirers turn out to have been right. That was my single worst miscalculation. Second, of course, was America’s invasion of Iraq. Like most of the rest of the mainstream press, I was for the war before it was against it. It took about four weeks to change its mind.

And the significance to the present day? It is two-fold.

The first has to do with is the carom shot that today’s is war in Ukraine. Instead of committing American forces to free the world from tyranny, the U.S. has offered intelligence and arms, and otherwise depended on the willingness of Ukrainian soldiers to repel the invaders of their homeland. Tens of thousands have died.

As Fareed Zakaria writes in the current Foreign Affairs, “America shouldn’t give up on the world it made.” Mike Johnson’s willingness to risk his speakership to build a bipartisan coalition ensure that America keeps its promises, as best it can. His choice is the true beginning of the end for Donald Trump.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com

David Warsh: Keynes and Freud

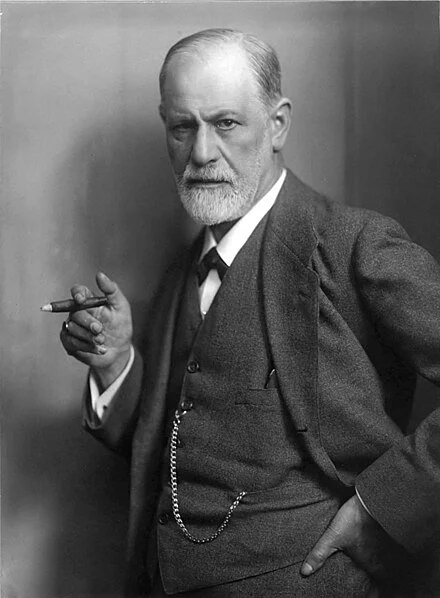

Sigmund Freud in 1921. His cigar addiction gave him oral cancer, which led to his death in London in 1939. He had fled there to escape the Nazis, after Hitler’s Germany had taken over Freud’s native Austria.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

This column has become interested in the difference of opinion between John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman with respect to their explanations for the causes of the Great Depression, Keynes blamed social aggregates within the economy itself for a sudden fall, Friedman blamed an inept Federal Reserve. History has shown that Friedman was right and Keynes wrong.

Last week I likened both men to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a split personality from the famous novel by Robert Louis Stevenson. The comparison seemed apt for Friedman, insofar as in contrast to the relative precision of his theorizing, the policies he recommended as a cultural entrepreneur, especially in Capitalism and Freedom, routinely departed from those I consider sensible. Alec Cairncross put the case for economic realism well in an address on the two hundredth anniversary of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations:

“We are more conscious perhaps than Adam Smith of the need to see the market within a social framework and of the ways in which the state can usefully rig the market without destroying its thrust. We are certainly far more willing to concede a larger role for state activities of all kinds, But it is a nice question whether this is because we can lay claim, after two centuries, to a deeper insight in determining the forces determining the wealth of nations or whether more obvious forces have played the largest part: the spread of democratic ideals, increasing affluence, the growth of knowledge, and a centralizing technology that delivers us over to the bureaucrats.”

The Jekyll/Hyde comparison seemed to work relatively well in Friedman’s case. Abolish Social Security? Stop licensing the professions beginning with physicians? Get rid of national health insurance? Hog-tie the Fed in crises? “Starve the beast” of government by cutting taxes to the bone? Come on, Mr. Hyde!

The comparison did not, however, suit Keynes . Even the excesses of “The End of Laissez Faire” stopped short of murdering his darlings. The challenge was to come up with a metaphor for Keynes that seemed to work.

Let’s try Sigmund Freud on for size.

Both men were born in the 19th Century, Freud in 1869, Keynes in 1883. Both came of age in a time of great excitement about the possibilities of new sciences. The Interpretation of Dreams appeared in 1905 and The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936.

Both men wrote extremely well, both sought to overturn substantial portions of the received wisdom of their respective fields, Keynes with an intuitive vision of macroeconomics (a term late supplied by Ragnar Frisch), Freud with psychoanalysis. Both depended on influential discussion groups to advance their views. Both achieved enormous influence on culture in their day. Both inspired celebrated biographies.

The economist was well acquainted with Freud’s work. Keynes told a friend he was reading through all Freud’s books. He wrote a letter to a magazine calling the psychoanalyst “one of the great, disturbing geniuses of our time.” I found no evidence that Freud read Keynes, but he didn’t look very far. Freud died in 1939, Keynes in 1946. Subsequent critics, mostly from the analytic community, have argued that Keynes’s view of human nature was very similar to that of Freud.

But the real similarity between the two scientists/latter-day culture entrepreneurs has to do with the posthumous influence of their work. Freud’s reputation as a successful scientific revolutionary and culture entrepreneur has been steadily diminished by advances in other branches of psychology, neurology and diagnostics.

Within technical economics. Keynes’s authority began to ebb in the ‘70’s Clarified an refined by generations of system builders, incorporated in formal models, “neo-Keynesian” views remain widespread. But macroeconomics is in flux today, and there is no way of telling how, in 20 or 30 years, Keynes’a contribution will be viewed.

This much seems likely: because he wrote so well, Keynes’s reputation in the humanities, like that of Freud, will prove to be imperishable.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: The split records of Keynes and Friedman

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

From the beginning I have been convinced that Milton Friedman possessed a dual personality, somewhat like Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde: a strong economist by day, a weak citizen by night. Nothing I’ve read and written about in the last nine weeks has convinced me otherwise, not even Edward Nelson’s meticulous explication ofFriedman’s professional life from 1929 to 1972.

Instead, my suspicions have grown with the passage of time that with John Maynard Keynes, it was the other way around. What if Keynes was a weak technical economist, but a strong citizen by night? Turning things on their heads after seventy-five years requires time, a critical biography by a first-rate economist in the future, and, in my case, not much more than cheek. I’ll sketch the bare bones of the argument here, and hope to return to it someday.

This puts me up against the judgment of Nelson and, worse, of Friedman himself. In Newsweek magazine, in 1970, he wrote:

“Now John Maynard Keynes was one of the greatest economists of all time. I know many people who regard him as a devil who brought all sorts of evil things into this world – he was not that; he was like rest of us; he made mistakes. He was a great man, so when he made mistakes, they were great mistakes. But he was a great man.”

But I am a journalist, not an economist, and it’s the mistakes that interest me, one of them in particular: his diagnosis of the causes of the Great Depression. Keynes regarded it as, like any recession, a drop in aggregate demand, moving economic output below the production capacity of the economy. In such circumstances, he argued, governments should counter recessions through an expansionary fiscal policy that boosts aggregate demand.

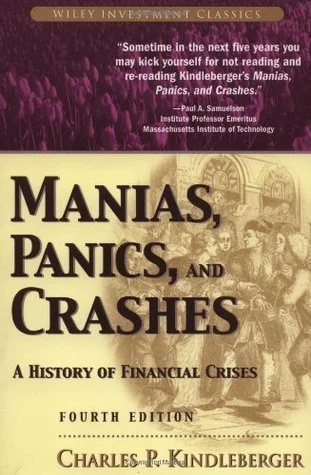

Friedman and his research partner Anna Schwartz advanced a different explanation of the Great Depression in their A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. Ben Bernanke, a leading scholar of the decade of the 1930s, before he became a central banker, summarized their argument this way: “central bankers’ outmoded doctrines and flawed understanding of the economy had played a crucial role in that catastrophic decade, demonstrating the power of ideas to shape events.”

In 2007-08. Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke, with the help of many others, forcefully demonstrated the power of better ideas. Together, they saved the world from a Second Great Depression.

Keynes may have had many brilliant ideas as an economist, but his single greatest success came as a journalist. The Economic Consequences of the Peace, his 1919 book, fiercely criticized the harsh reparations demanded of Germany in the wake of World War I, correctly foresaw the causes of World War II, and supplied the foundations of the 1947 Marshall Plan, aimed at the reconstruction of Germany, not punishment for its many sins.

My friend, Peter Renz like me, a non-economist, described the essence of Keynes this way: “a romantic figure. A polymath, brilliant as a writer, alive with charm as a lover, witty, political, a man of business and action.”

In this view, Keynes, born in 1883, was the last eminent Victorian of a certain sort. He was not included in that volume of portraits written by Keynes’s friend Lytton Strachey. Perhaps he, along with Friedman, will appear in a volume by some latter-day Strachey. (The figment of my imagination is the tenth good book). Meanwhile, I can’t do better than Wikipedia’s summary of the original:

“Eminent Victorians is a book by Lytton Strachey (one of the older members of the Bloomsbury Group), first published in 1918, and consisting of biographies of four leading figures from the Victorian era. Its fame rests on the irreverence and wit Strachey brought to bear on three men and a woman who had, until then, been regarded as heroes: Cardinal Manning, Florence Nightingale, Thomas Arnold and Gen. Charles Gordon. While Nightingale is actually praised and her reputation enhanced, the book shows its other subjects in a less-than-flattering light, for instance, the intrigues of Cardinal Manning against Cardinal Newman.”

And Friedman? He had two great successes as an economist. One of them should be clear by now. That single chapter of the Monetary History makes engrossing reading. It has its flaws – the significance it assigns to the 1930 failure of the grandly named Bank of the United States, a hastily assembled commercial bank in New York City, chartered in 1913, seems overblown – but overall, Friedman’s and Schwartz’s analytic narrative of the series of banking panics that unfolded 1930-33 is convincing.

Friedman’s other achievement is more diffuse but more important. He brought monetary analysis back into the big tent of economics that that had been dominated for more than a century by analysis of “real” goods and services by the forces of supply and demand. I keep on the shelf above my desk two little Cambridge Handbooks of 1922, Supply and Demand, by H. D. Henderson, and Money, by D. H. Robertson.

That was the situation before Keynes. In his General Theory, he sought to unite them, but the makers of macroeconomics who followed him somehow have failed to come up with an account of a business cycle without periodic financial crises.

“Monetarism,” a slogan that Friedman is said to have disliked, as opposed to “monetary theory,” doesn’t do much better, but at least it puts central banks back in the the story. As for rules as an alternative to occasional discretion, as a means of deflecting the occasional crisis? I doubt it.

And Friedman’s dark side? Nothing worse than being the most prominent spokesman for an exaggerated version of the common failing of today’s economics – its emphasis on the role of the individual, at the expense of attention to his/her/their entanglement in society (in Herbert Gintis’s phrase). British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher famously proclaimed “There’s no such thing as society.” That’s bunk, even worse than macro without crises.

At least the tale of Jekyll and Hyde is the story one journalist has to tell.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: What an economist and public servant! And his brother was a spy

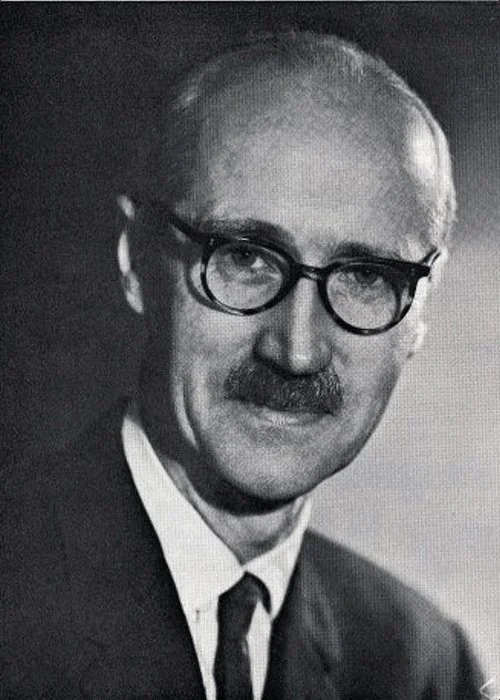

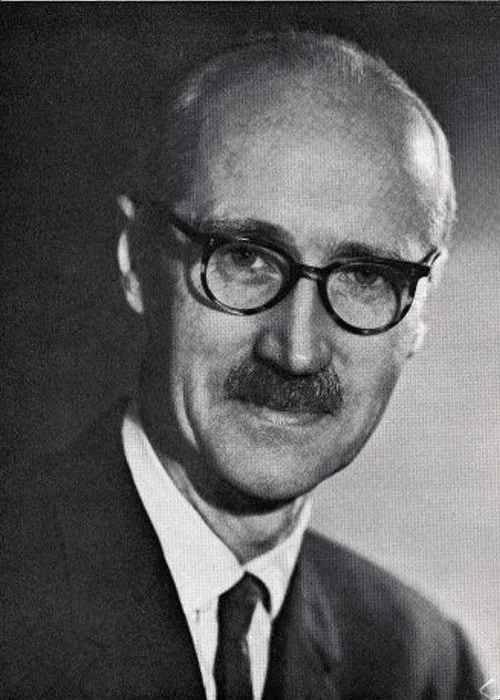

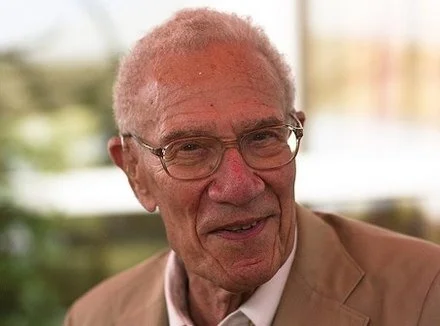

Sir Alexander Cairncross

Milton Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in 1976, but something more important to economics happened that year, and I don’t mean the bicentennial of the American Revolution. The Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith appeared that year as well, timed to commemorate the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations.

“Modern economics can be said to have begun with the discovery of the market,” began Sir Alexander Cairncross, chancellor of the University of Glasgow, in his opening address to the convocation that introduced the new edition.

He continued:

“Although the term ‘market economy’ had yet to be invented, its essential features have debated the strength and limitations of market forces [ever since] and have rejoiced in their superior understanding of these forces. The state, by contrast, needed no such discovery.”

Cultural entrepreneurs in economics, even the most effective among them, such as John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, do their work against the background of hard-earned knowledge of others, standing on the shoulders of giants and all that.

Eight beautiful volumes had rolled off the presses: two containing The Wealth of Nations; another with Smith’s first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments,; three more volumes of essays, on philosophical subjects (which includes the famous essay on the history of astronomy), jurisprudence, and rhetoric and belles letters; a collection of correspondence and some odds and ends; and, in the eighth, an index to them all.

Each contains introductions by top Smith scholars, with edifying asides tucked in among the footnotes. Two companion volumes accompanied the release, published by Oxford University Press: Essays on Adam Smith, and The Market and the State: Essays in Honor of Adam Smith, by way of penance. Smith had been educated at the University of Glasgow but scorned Oxford, where he spent six post-graduate years, mostly reading. Inexpensive volumes of any or all of the Glasgow edition can be had from the Liberty Fund.

A feast, in other words, for those interested in thinking about such things.

One such was Cairncross, whose Wikipedia entry begins this way:

“Sir Alexander Kirkland Cairncross KCMG FRSE FBA (11 February 1911 – 21 October 1998), known as Sir Alec Cairncross, was a British economist. He was the brother of the spy John Cairncross [worth reading!] and father of journalist Frances Cairncross and public health engineer and epidemiologist Sandy Cairncross.”

More to our point, for twenty-five years Cairncross was chancellor of Glasgow University (1971-1996). It was he who commissioned the Glasgow edition of Smith. He delivered the inaugural address I quoted above.

Before that, however, Cairncross became an economist, as an under graduate at Glasgow and then, beginning in 1932, at Trinity College, Cambridge, under John Maynard Keynes and his increasingly incensed rival, Dennis Robertson. Keynes published his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money to great excitement in 1936; Robertson steered Cairncross away from theory and into applied economics. After graduating with honors, he returned to Glasgow as a lecturer and wrote a textbook.

His service in government during World War II and after was extensive and exemplary: the Ministry of Aircraft Production; Treasury representative at the Potsdam Conference; a stint at The Economist; adviser first to the Board of Trade, then to the Organization for European Economic Cooperation; 10 years as Professor of Applied Economics at Glasgow; then, for another decade, various high-ranking positions in the Treasury. The appointment as Glasgow’s chancellor came in 1971.

If you are interested in post-war Britain, particularly the Sixties, the Royal Academy’s biographical minute on Cairncross makes interesting reading. Quietly told in 1964 about his brother’s treachery as a paid agent of the KGB, he called it “perhaps the greatest shock I ever experienced.”

Cairncross was a Keynesian economist, his biographers say. He was critical of monetarism and dismissed the idea of a “natural” rate of unemployment as absurd. He considered that industrial planning, while necessary in wartime, was no model for peacetime governments. Cairncross “shows that you don’t have to be flamboyant to achieve great influence,” wrote a former boss, “and that you do not have to be malicious to be interesting.”

“By some odd quirk of memory,” his biographers write, in his autobiography, A Life in the Century, Cairncross neglected to mention the Glasgow edition of the works of his fellow Scot that he commissioned, “although he himself had given the opening paper.” Yet that comprehensive record of the circumstances, and, at their center, the founding work – An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations – from which modern economics emerged may have been his single most durable accomplishment. Cairncross concluded his introductory address to the convocation this way:

“We are more conscious perhaps than Adam Smith of the need to see the market within a social framework and of the ways in which the state can usefully rig the market without destroying its thrust. We are certainly far more willing to concede a larger role for state activities of all kinds, But it is a nice question whether this is because we can lay claim, after two centuries, to a deeper insight in determining the forces determining the wealth of nations or whether more obvious forces have played the largest part: the spread of democratic ideals, increasing affluence, the growth of knowledge, and a centralizing technology that delivers us over to the bureaucrats.”

For an accounting of the lives among the bureaucrats of some distinguished present-day economists, see this column next week.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: The outside helpers who helped make Keynes and Friedman iconic

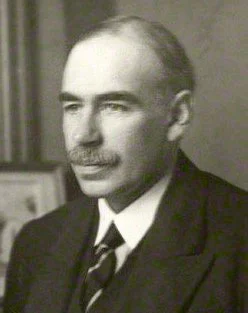

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946).

Keynes was a key participant at the Bretton Woods conference, which lay the foundation for much of the world’s financial system after the devastation of World War II.

The conference took place at the Mount Washington Hotel. Clouds here obscure the summits of the Presidential Range.

— Photo by Shankarnikhil88

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman traveled different paths to become the dominant policy economists of their respective times. In The Academic Scribblers, in 1971, William Breit and Roger Ransom invoked the motto of the Texas Rangers to explain Friedman’s success: “Little man whip a big man every time if the little man is right and keeps a’comin’.”

But there was more to it than that.

Both Keynes and Friedman were slow starters and late bloomers. “It was The Economic Consequences of the Peace [in 1919] that established Keynes’s claim to attention”, as biographer Robert Skidelsky wrote at the beginning of the second volume of his trilogy. In murky circumstances, the prescient warning about the hard terms imposed on Germany after World War I failed to be recognized with a Nobel Prize for Peace, as Lars Jonung has shown. Not until 1936, with the appearance of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, when he was 58, did Keynes acquire the sobriquet that Skidelsky confers on him in that second tome, “the economist as savior.”

Friedman was 50 when, in 1962, he published both Capitalism and Freedom and, with Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. He was nearly 40 when he turned to monetary theory. Within the profession he enjoyed growing success in the ‘50’s and ‘60’s. But vindication and celebrity waited until 1980, when he turned 69, as Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker battled inflation under a monetarist banner; when Friedman’s television series Free to Choose, with his economist wife, Rose. was broadcast on America’s public network; and when Ronald Reagan was elected president.

Both Keynes and Friedman freely offered advice to American presidents, which only enhanced the economists’ stature. Keynes, at arm’s length, disparaged Woodrow Wilson; encouraged Franklin Roosevelt, whom he admired, and, 15 years after his death, saw his policies adopted by John F. Kennedy. Friedman, after a 1964 unsuccessful campaign with Barry Goldwater, enjoyed considerable influence with Richard Nixon and Reagan.

So, how did the Keynesian Revolution roll out in America? There are many accounts of the process by economists, but only one by an economic historian of how America’s leading most trusted newspaper columnist first resisted, then was convinced, and facilitated the movement’s acceptance for the next 40 years. (Michael Bernstein’s A Perilous Progress: Economics and public purpose in twentieth century America (Princeton University Press, 2001) surveys the period from a somewhat different angle.)

Walter Lippmann was already America’s foremost public intellectual, a common enough species today, but then more or less one of a kind. He published A Preface to Politics a year after graduating from Harvard College, studied Thorstein Veblen and Wesley Clair Mitchell, made friends with Keynes when both attended the Versailles Peace Conference, in 1919, compared notes with U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, scientists, philosophers, central bankers, lawyers, corporate leaders and Wall Street financiers.

Lippmann began writing an influential newspaper column in the Depression year of 1931. For a taste of how different that world was from our own. I recommend a viewing of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. In Walter Lippmann: Public Economist (Harvard, 2014) the late Craufurd Goodwin, of Duke University, traces the twists and turns of Lippmann’s columns as he sorted through various explanations of the Great Depression – too much free trade, too little gold, too many monopolies, unbalanced budgets, before becoming convinced that more public public spending was the key to recovery.

After World War II, Lippmann grew close to MIT’s Paul Samuelson. He tracked the debates of emerging “neo-liberal” factions, including leaders F. A. Hayek and Friedman, but declined to join the Mont Pelerin Society. His influence as a columnist finally came to grief over his prolonged support for the War in Vietnam, and he died, at 85, in 1974.

The sources of Friedman’s support are more complicated. Within the profession he had many key allies– his Rutgers professors Arthur Burns, later chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, and Homer Jones, later research director of Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; his graduate school friends, George Stigler and Allen Wallis; his brother-in-law Aaron Director, later dean of the University of Chicago’s Law School; his co-author Anna Schwartz; and, of course, his wife, economist Rose Director Friedman, to name only his closest associates. These were among his fellow Texas Rangers.

It has been Friedman’s acolytes outside the profession who were quite different from those of Keynes. The story of the law and economic movement has been well told by Steven Teles in The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The battle for control of the law. On the financialization of markets, no one has yet topped Peter Bernstein’s Capital Ideas: The improbable origins of modern Wall Street. Friedman’s contribution to globalization is discussed in Three Days at Camp David: How a secret meeting in 1971 transformed the global economy, by Jeffrey Garten. The story of various business anti-regulation and anti-tax lobbying groups can be found in Free Enterprise: An American history, by Lawrence Glickman

It’s not that economics departments weren’t also special-interest groups, but they are special interests of a different sort, organized as competitors, which permits swift reversals within the profession itself. Whether that is the case with the legal, financial, corporate, and media industries remains to be seen. Maybe; maybe not.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: We continue to live with 'cameralism'

F.A. Hayek (1899-1992), the famed European philosopher and economist, hated what MIT economist Paul Samuelson dubbed the “modern mixed economy.’’

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

From its beginnings, in 1947, the Mont Pelerin Society sensed a problem, which its members understood better than most. In the aftermath of World War II, amid the smoldering ruins of Europe, it was impossible not to be repelled by the two familiar examples of government planning, Hitler’s National Socialism and Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution.

But the philosophers, historians, economists and journalists who formed the market advocacy group Mont Pelerin Society knew that the roots of government planning went much deeper than that.

In 1727, The King of Prussia established a chair of “Oeconomie, Policy, and Kammer-Sachen” at the University of Halle, at a time when, across the North Sea, Adam Smith was three years old. In his address on the occasion, the chancellor of the university noted that the concerns of the new discipline went far beyond what was to be found in Aristotle.

“What happens in the fields, meadows, ponds, woods, gardens or relate to planting; how to treat cattle in their stalls; how to increase manure; how to brew and sell corn; the task of a husbandman on every day of the year what reserves to lay by and how to stock a storeroom; how to properly organize kitchen and cellar; what to keep and what to distribute: not a word of this appears in Aristotle.”

“Kammer-Sachen” means something like legislative and judicial matters, the word Kammer meaning chamber, as in the private office of a judge. The idea of a science of governmental planning – oversight of what today its critics call “the administrative state” – was an Enlightenment project, shaped by the ideals that took hold in the years before the French Revolution. Conceptions of husbandry – of the systematic promotion of good order and happiness within the state – is older than classical economics.

You can follow the development of cameralism – meaning, loosely, government planning and oversight – in Strategies of Economic Order: German economic discourse 1750-1950 (Cambridge, 1995), by Keith Tribe, an independent economic historian and author of several well-received books. You may need the occasional help of a good German-English dictionary.

Cameralism is, roughly, what Adam Smith labeled mercantilism, or “the commercial system,” in contrast to his own market-based “system of natural liberty,” which he laid out in 1776 in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Smith defined mercantilism as an export-oriented and monetary strategy, managed by the state, in cooperation with well-ensconced business interests, in competition with other states.

In Friedrich List’s critique of The Wealth of Nations, published in English in 1846 as The National System of Political Economy, cameralism sounds more like a heavy-handed version of today’s macroeconomics – a true political economy, journalist List wrote, as opposed to Smith’s cosmopolitan economics.

In nine painfully erudite scholarly chapters, Tribe traces the course of the German persuasion from List through Max Weber, Ludwig von Mises and Otto Neurath to F. A. Hayek, organizer of the Mont Pelerin Society. He finishes with an analysis of the Nazis’ grand plans for Europe, noting its similarities to, and differences from, the European integration that eventuated after 1945.

Some of this background, but not much, is to be found in The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Great Depression (Harvard, 2012), by Angus Burgin, of Johns Hopkins University. (There is only so much an author can tell in one book.) A chapter on “moral capital” elucidates fears in the 1970s among neoconservatives – Irving Kristol, for example, a socialist in his youth – that libertarian capitalism was eroding “traditionalist” values. This was, in effect, living off the “accumulated moral capital” of social philosophies that it had supplanted, Kristol wrote, in declining an invitation to join the Mont Pelerin Society.

Already in 1935, while living in London, Hayek was sufficiently alarmed by the drift of things to collect several of his essays in Collective Economic Planning (Routledge, 1935). In “The Nature and History of the Problem,” he put his diagnosis most clearly.

“If we are to judge the potentialities aright, it is necessary to realize that the system under which we live choked up with attempts at partial planning and restrictionism is almost as far from any system of capitalism which could be rationally advocated as it is different from any consistent system of planning. It is important to realize in any important investigation of the possibilities of planning that it is a fallacy to suppose capitalism as it exists today is the alternative. We are certainly as far from capitalism in its pure form as we are from any system of central planning. The world of today is just intervention chaos.”

Not much changed in Hayek’s views between then and the time he wrote The Road to Serfdom, in 1944, still living in England. He had declared firm opposition to what, in 1948, would be described in the United States, in Paul Samuelson’s introductory textbook, Economics, as “the modern mixed economy.”

It doesn’t take more than a high-school diploma to recognize that much of America’s institutional mixture had been borrowed from German culture, some of it recently – from kindergarten to research universities and business schools, from government civil service to industrial safety, from rural electrification to road-building, from social insurance (retirement, medical, disability) to wage-bargaining and bank regulation.

Hayek may have longed for systemic purity, but it was Milton Friedman who put into action plans to purge its elements of cameralism, with two books of his own. Capitalism and Freedom, in 1962, espoused the economics of Barry Goldwater’s 1964 campaign. Free to Choose, in 1980, set out what Friedman hoped would be Ronald Reagan’s platform for governing.

For example, in 1962, Friedman proposed to dismantle discretionary central banking, fixed exchange rates, public education, conscription, anti-discrimination policies, corporate social responsibilities, trade unions, professional licensing and compulsory social insurance, including the Social Security System.

Friedman had stupendous success as a cultural entrepreneur. Many of the measures he proposed have been adopted. Final returns are far from in on many of them – the all-volunteer military, for example. But one major strut may have already turned out to be disastrous, at least for one prominent company in the news.

In an influential essay in the New York Times Sunday magazine, in 1970. Friedman argued that “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits.” Business leaders who promoted desirable “social” ends – providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution “and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers” – were “preaching pure and unadulterated socialism.”

A publicly owned corporation had only one ‘‘social’’ responsibility, Friedman concluded: “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” That meant increasing share prices, a goal easily measured and properly rewarded by compensating executives who achieve good results.

The doctrine of shareholder sovereignty is mentioned only in passing on page 474 of Jennifer Burns’ biography, Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 2023. But from Friedman’s argument to today’s problems at Boeing Co. seems to me a straight line of descent. At Airbus, in Europe, the legacy of cameralism flies on.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: About the economics giant Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman in 2004.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The appearance of a long-awaited biography of Milton Friedman (1912-2006) has afforded me just the opportunity for which my column, Economic Principals (EP), has been looking. Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative (Farrar, Straus, 2023), by historian Jennifer Burns, of Stanford University, offers a chance to turn away from the disagreeable stream of daily news, in order to think a little about the characters who have populated the stage in the fifty years in which my column, EP has been following economics.

None was more central in that time than Friedman. We first met in his living room, in April, 1975, on a morning when he and his wife were packing for a week-long trip to Chile. We talked for an hour about the history of money. I left for my next appointment. Eighteen months later, Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Prize. I have followed his career ever since.

Ms. Burns’s book is a thoughtful and humane introduction to the life of an economist “who offered a philosophy of freedom that made a tremendous political impact on a liberty-loving country.” Standing little more the five feet tall, Friedman managed to influence policy, not just in the United States, but around the world: Europe, Russia, China, India, and much of Latin America.

How? Well, that’s the story, isn’t it?

Friedman grew up poor in Rahway, N.J. His father, an unsuccessful merchandise jobber, died when he was nine. His mother supported their four children with a series of small businesses, instilling in each child a strong work ethic. Ebullient and precocious, Milton was the youngest.

A scholarship to nearby Rutgers University put him in touch with economist Arthur Burns, then a 27-year-old economics instructor, forty years later Richard Nixon’s chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Burns took Friedman under his wing and pointed him toward the University of Chicago. He arrived in the autumn of 1932, as the Great Depression approached its nadir.

Ms. Burns unpacks and explains the doctrinal strife that shaped Friedman and their friends encountered there. They include Rose Director, a Reed College graduate from Portland, Ore., who, improbably in those hard times, had enrolled as a economics graduate student at the same time. The two became friends; they parted for a year, while Milton studied at Columbia University and Rose considered her options in Portland; then returned to Chicago, becoming a couple, as members of the “Room Seven Gang” in the campus’s new Social Science building. Other members included Rose’s older brother, Aaron, a future dean of the university’s law school; George Stigler, who would become Friedman’s best friend; and Allen Wallis, an important third musketeer.

Distinctly not a member of that gang of graduate students was Paul Samuelson, a prodigy who had enrolled as an undergraduate, at 16, nine months before Friedman arrived to begin his graduate studies. Already tagged by his professors as a future star, Samuelson was clearly brilliant, but impressed the Room Seven crowd as being somewhat toplofty.

All this, rich in details and explication, is but preface to the story. Ms. Burns follows the Friedmans to New Deal Washington, where they marry and work for a time; to New York, where Milton pursues a Ph.D. at Columbia and Rose drops out to start a family (neither undertaking turned out to be easy); to Madison, Wis., where the couple spent a difficult year while Friedman taught at the University of Wisconsin, before returning to wartime Manhattan, to be reunited with Stigler and Wallis, working at Columbia’s Statistical Research Group.

In 1945, the major phases of the story lay ahead: Friedman’s return to Chicago, to form a faculty group sufficiently cohesive to become recognized as a “second Chicago school,” significantly differentiated in important ways from the first; his embrace of monetary economics; his battles with other research groups seeking to shape the future of the profession. These included the Keynesians and organizational economists in Cambridge, Mass., the game theorists in Princeton, the mathematical social scientists at Stanford and RAND Corp., in California.

By 1957, Friedman had opened a political front. Lectures given at Wabash College in 1957 become a book, Capitalism and Freedom, in 1962. The book earned well, and the couple named “Capitaf,” their Vermont summer house for it. A Monetary History of the United States, with Anna Schwartz, all 860 unorthodox pages of it, appeared the same year. In 1964 Friedman was invited to become chief economic adviser to presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, much as Paul Samuelson had advised John F. Kennedy four years before,

The Bretton Woods Treaty, a hybrid gold standard arrangement negotiated in 1944, by Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, began to crumble; Friedman was ready with an alternative: flexible exchange rates determined in international currency markers. Distaste with the war in Vietnam exploded. Friedman proposed an all-volunteer army: that is, market-based wages for soldiers. Inflation grew out of control in the Seventies; Friedman had a ready answer, simply control the money supply. Just ahead are Margaret Thatcher, Paul Volcker, and Ronald Reagan. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement, by Milton and Rose Friedman, a 10-part public television series, appears in 1980, becoming an international best-seller, followed by a book.

But that is getting ahead of the story here. Ms. Burns relates all this and its surprising conclusion with grace and attention to detail. No wonder it took nine years to write! In the end it offers a seamless account. But in that very seamlessness lies a rub.

Ms. Burns is a cultural historian, concerned with rise of the American right, which in the 1950s seemed to come out of nowhere: The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich Hayek (Chicago, 1944); Sen Joe McCarthy; the John Birch Society; God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (Regnery, 1951), by William F. Buckley Jr.; The Conscience of a Conservative (Victor, 1960), by Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, and the subsequent Goldwater presidential candidacy, and all that. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford, 2009) was her previous book. She knows Friedman’s influence on economics was great – too great to cover adequately in her book. Even the subtitle raises more questions than the book itself can answer.

Therefore, as I continue to peruse Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, I intend to write over the next nine weeks about nine different books, each of which covers some aspect of Friedman’s story from a different angle. Trust me, the story is worth it: you’ll see. Meanwhile, if you get tired of reviewing the last seventy-five years, there is always the dismal news in the newspapers today.

. xxx

In a rush last week to get something into pixels about the American Economic Association meetings in San Antonio, I committed an embarrassing error.

Michael Greenstone, of the University of Chicago, delivered the AEA Distinguished Lecture, not Emmanuel Saez. You can find “The Economics of the Global Climate Challenge” here. If you care about climate warming, or simply want a glimpse of where the economics profession is headed, Mr. Greenstone’s lecture is well worth the hour it takes to watch.

That the Princeton Ph.D. and former MIT professor is today the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor and former director of the Becker-Friedman Institute adds authority to his message.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Despite it all, I think that Biden will win

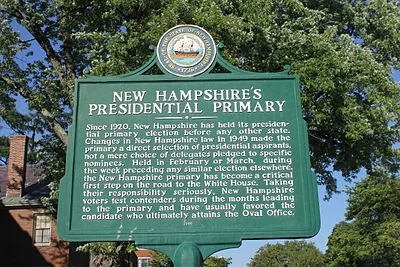

Plaque in Concord, N.H.

The Balsams Grand Resort Hotel, in Dixville Notch, N.H., one of the sites of the first "midnight vote" in the New Hampshire primary.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

This column, named Economic Principals (EP), began forty years ago in The Boston Globe with a commission to write about goings-on within and around the economics profession. It didn’t take long to discover that few readers were sufficiently curious to warrant a sustained diet of economics with a capital E, and so a second column was added, this one about economics and politics.

Becoming unmoored from the newspaper in 2002 has made the mix somewhat richer on political topics, all the more so the tumultuous last few years. In fact, I intend to spend more time on economics, not less, during the next year or two. However, I want to venture a bet on the year – a bet against political acumen.

Of all the issues that EP follows – the wars in Ukraine and the Mid-East, immigration, China, central bank policy, climate change – none is as important this year as the November elections in the United States.

It now seems nearly certain that we Americans are stuck with a re-run of the 2020 election, Joe Biden vs. Donald Trump. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’s campaign dissolved in a cocktail of timid captivity to the Trump base and internal dissension. Former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley’s gaffe on a voter’s Civil War question revealed all too clearly the dangers of playing to the Trump side of the aisle in the Republican primaries. Big government caused it, she said, failing to mention slavery.

For conventional wisdom in senior Republican Party circles, EP turned, as it does every Wednesday, to Karl Rove, who writes a column in the editorial pages of The Wall Street Journal. A veteran political operative since Richard Nixon’s 1972 re-election campaign, he served as senior adviser to President George W. Bush, and afterwards wrote quite a good book about President William McKinley’s place in GOP history. Rove has the added virtue of making an annual batch of predictions, and toting up the results a year later.

Rove’s presidential prediction for 2024:

“Biden vs. Trump is a chaotic, nasty mess. Mr. Biden counts on Mr. Trump being convicted and voters adjusting to inflation’s effects. Mr. Trump counts on anger over a politicized justice system and Mr. Biden’s age and mental capacity. Most vote for whom they hate or fear less. Mr. Trump is convicted before November yet wins the election while Mr. Biden receives a plurality of the popular vote. The race is settled by fewer than 25,000 votes in each of four or fewer states. Third-party candidates get more votes in those states than Mr. Trump’s margin over Mr. Biden. God help our country.”

EP has in mind the Kansas abortion referendum, of 2022. A ballot initiative amendment to the state constitution had been scheduled for August that year that would have criminalized routine abortions and given the state government the power to prosecute individuals involved in procedures. Six weeks earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court had overturned Roe V. Wade.

The Kansas amendment failed by an 18-point margin, a result ascribed to strong voter turnout and increased registration in the weeks leading up to the vote. In November, 2023, Ohio voters overwhelmingly embraced a constitutional amendment guaranteeing residents access to abortion, becoming the seventh state to affirm reproductive rights in one way or another since the Supreme Court decision.

As Kansas and Ohio voters rejected the Supreme Court’s decision, American voters have the opportunity in the November election next year to overturn the Trump wing of the Republican Party, and not just not just in so-called “battleground states,” of Georgia, North Carolina, Arizona, Nevada, Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania The available mechanism is the same in each case – high voter turnout.

True, Biden’s margin of victory in 2020 was far from a landslide. (Rove thinks this one will be closer.) The element of immediacy will be missing this year, though scheduled trials of the former president will refocus attention on the calculations that led up to the Jan. 6 insurrection. Those annoying third-party candidates are a wild card, as well.

By Novembers, the stakes will be clear. Never mind the avalanche of advertising spending about to descend. Work on getting voters to show up. We are a few good speeches away from resolving the issue. Biden offers some attributes to dislike, many fewer traits to fear.

Americans will try Donald Trump in the courts, reject him in the election. Biden will be re-elected by a clear-cut margin in the autumn. That’s the bet, based on not much more than a hunch. See you here next Dec. 29, to settle up or collect.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this columnist originated.

David Warsh: Getting personal about the Israeli-Hamas warTheY

Hamas logo

The Israeli flag

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Is it possible to criticize Israeli policy in Gaza and the West Bank without being anti-Semitic? The question seems worth asking, even if it almost certainly means being called anti-Semitic by some. Surely it is possible to deplore Hamas without being called anti-Palestinian.

I don’t know what to do with this except to be personal about it.

I grew up in a suburb of Chicago in which racism was pervasive, though mostly polite, because no people of color lived there. Unspoken replacement theology held sway – that is, the premise that Jews, followers of the Old Testament – the Hebrew Bible – eventually would be converted to the principles of the New Testament, the Christian Bible.

Folkways of the village in the Fifties exhibited some pretty strange ideas about gender, too. The use of atomic bombs and carpet bombing against civilian populations during World War II raised few objections. And as for the indigenous populations we had displaced? The hockey team was named for them.

A large part of my education since has involved escaping those prejudices, by degrees, via participation in “movements” of various sorts: college, civil rights, anti-war, pro-women, and now, opposition to Israel’s “Second War of Independence;” that is, its special military operation in Gaza.

Revolted as I was by the Hamas raid, my first reaction to the news of the massacre of some 1,200 innocents was to ask myself what Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu should have done? I had grown up to become a member of a Congregational church; I could use my confirmation instead of a birth certificate to obtain a passport, or so I was told. For a time, I had been a Zionist: I knew a good deal about the Holocaust; I had thrilled to the film Exodus in high school.

Netanyahu should have turned the other cheek, I thought, called out Hamas to worldwide disgust and scorn, and resigned. It took only a day to realize that recommending the Sermon on the Mount to the Israeli Defense Force was no solution. That set in motion this skein of thought.

I had never seen, until I came across the other day, , in an article in The Atlantic, President Dwight Eisenhower’s advice in a letter to one of his brothers, in 1954, in the early stages of the Cold War:

You speak of the “Judaic-Christian heritage.” I would suggest that you use a term on the order of “religious heritage” – this is for the reason that we should find some way of including the vast numbers of people who hold to the Islamic and Buddhist religions when we compare the religious world against the Communist world. I think you could still point out the debt we all owe to the ancients of Judea and Greece for the introduction of new ideas.

Advice as sage today as it was then. Even much-loathed former Commies might be included in the heritage of humanity today. I’ll leave it to historians, Biblical scholars, ethnologists, anthropologists, and sociologists to pick apart the differences. But theologian Paul Tillich’s phrase “Judaic-Christian heritage,” which offered such comfort during the years after World War II, is no longer part of my vocabulary.

Having said this much, I must come to the point. I am aghast at the Israeli government’s invasion and occupation of Gaza; appalled by its plan to occupy the territory after the slaughter stops; embarrassed by the United States’ veto of the 13-1 United Nations Security Council resolution calling for an immediate cease-fire.

I object to the congressional and donor bullying of university presidents. The American newspapers I follow seem to have been somewhat intimidated as well. (Here is a long view of the situation in The Guardian that makes sense to me.) The stain on the reputations of the leaders and policymakers involved, including those in the United States and Iran, can never be erased.

I have had this privilege of writing this column, called Economic Principals, for 40 years. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t say this much about current events in the Middle East. It is, however, as much as I have to say. I’m against the war in Ukraine, too, but after twenty years of following its genesis, it is a problem I know something about.

The relevance to these matters of economics should be clear, at least intuitively. I pledge to work harder to spell it out.

xxx

Swedish Television does an excellent job on its short profiles of each year’s well Nobel laureates. The link offered here last week to their visit with Harvard economist Claudia Goldin didn’t work. Here is one that does. At fourteen minutes, it is well worth watching.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

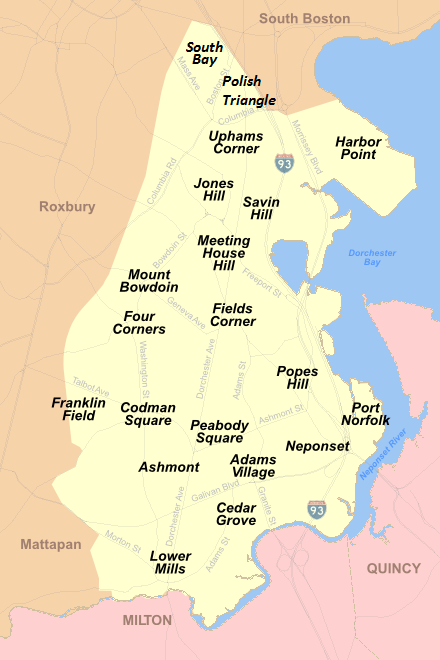

David Warsh: Dorchester's weekly paper plows on through the decades

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Rupert Murdoch is stepping down as chairman of Fox and News Corp, having built the little Australian newspaper he inherited at the age of 21 (The News of Adelaide, circulation 75,000) into a global multi-media complex of enormous political influence. He is to be succeeded by his elder son.

Myself, I have been preoccupied recently with the saga of The Dorchester Reporter, which celebrated the 40th anniversary of its founding with an ebullient party in Boston on Sept. 14.

That “every banker has one good idea” is an old-time industry joke. Ed Forry’s good idea was to get out of the business. In 1983, at age 39, with banking deregulation accelerating, he quit his $24,000-a-year job as a savings bank executive to found a community newspaper in Boston’s largest neighborhood. Dorchester was then recovering from a decade of white flight to the suburbs,

Forry had some experience to start with: confirmed in St. Gregory’s Parish, he had graduated from Boston College High School and Boston College. As a community activist, he had written a column for the Dorchester Argus-Citizen, with which Forry had created a profitable yearbook business. His wife, Mary Casey Forry, would be an all-in partner. The couple had two young children and $5,000 in the bank.

The Reporter circulated monthly for several years. At first, advertising paid the way. The monthly went weekly, paid subscriptions were introduced, circulation grew. There were hard times. In 1993, as recession lingered, Forry laid off the entire staff of nine. Mary Forry died in 2004. By then, son Bill had joined the business, to become, eventually, executive editor and publisher. He married Linda Dorcena Forry, a Haitian-American who won election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 2005, then moved on to the state Senate, where she held a seat until 2018. For an account of those first 25 years, read the story by Boston Globe columnist Jack Thomas.

What is the business worth today? Decent livings for its eight fulltime staffers, paid gigs for its regular lineup of columnists and critics, and opportunities for interns and freelance writers. The paper has disproportionate political influence —-Boston Mayor Michelle Wu and U.S. Sen. Ed Markey spoke at the party — and retained earnings, and has considerably enhanced Dorchester pride.

xxx

In 1963, at the opposite end of the enterprise spectrum, a married couple of lawyers from Brooklyn saw promises in the California building boom and purchased the Golden West Savings and Loan Association in Oakland. In a go-go market of 1968, they made a public offering, Over the next 40 years, Herbert and Marion Sandler ran the most successful residential-mortgage lender in the country, until they sold the firm in 2006 at the top of the market for $24 billion to a North Carolina bank. Widely blamed – in their view unfairly – for the subprime housing-mortage crisis, they commenced a long-planned entry into the philanthropy business.

Among many other overtures, they called Paul Steiger, who for 16 years had been editor of The Wall Street Journal, which was just the being acquired by Rupert Murdoch. The result, in short order, was ProPublica, with an annual budget of $10 million, for the practice of WSJ-style investigative journalism.

Steiger hired as his successor Stephen Engleberg, an 18-year veteran of The New York Times. Effective fund-raising raising increased the annual budget to $40 million. So with a staff of a hundred or so well-seasoned journalists, ProPublica has established itself as the most successful of philanthropically endowed news organizations that have arisen among the ruins of the old advertising-supported metropolitan print press.

What’s the second-best nonprofit news organization? National Public Radio, at least in my view. And though it is reasonably well endowed, it has recently beginning a new fund-raising campaign. Lacking the same marriage of top newspaper cultures, its enterprise ventures in news are somewhat lower-key. And lacking undisputed foundational principles, it is susceptible to the regular political tempests that afflict Washington D.C.

xxx

Now back to Murdoch. How did he do it? Mostly by buying newspapers properties in down markets, then building them up experimentally instead of stripping them down. Fox News, which he founded in 1996, with former Richard Nixon pollster Roger Ailes, was a particular success; MySpace, an early competitor to Facebook, didn’t fair nearly as well.

Murdoch, 92, and in good health, has put his first-born son, Lachlan, in charge of all of the empire. But further struggles maybe in store. The mogul has three other children; they are entitled to equal shares under terms of his will. The conglomerate can be disassembled and shared out. But the conglomerate’s Wall Street Journal will probably power on.

That in turn leads to The Washington Post. When Donald Graham sold his family-controlled newspaper to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos for $250 million, in 2013, it was for far less than might have been offered by other bidders. Why was that? Consider that as one of the world’s richest men, Bezos possessed both the means and the moxie to restore one of America’s three leading newspapers to robust good health. Yet it can’t have escaped Graham’s attention, either, that Bezos has four children. Thus the Post’s independence will be preserved well into the future. That seems to have been a central aim of the public-spirited Graham.

Finally, that leads back to Boston. When the New York Times Co, sold The Boston Globe to Boston Red Sox owner John Henry, in 2012, for $70 million, having mismanaged the property for more than a decade, the direction of the paper itself fell to Henry’s wife, Linda, a native Bostonian. She has managed to keep it not just afloat, but interesting. It is profitable, she says, though print circulation continues to decline.

At a Globe conference on the new business last week, she spoke proudly of new bureaus in Rhode Island and New Hampshire. We’re not interested in becoming a national [paper],” she told listeners, “but as there’s been a decline in smaller regional places, we’re trying to fill that gap.”

In Dorchester, meanwhile, the money comes from putting newsprint on the front porch. The Dorchester Reporter probably out-influences the old Boston Herald, once owned by News Corp and now operated out of suburban Braintree by Media News Group, and, at least in municipal politics, often rivals The Globe itself.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Economicprincipals.com is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support Mr. Warsh’s work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

David Warsh: Secular time and political time

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

So Joe Biden is sticking with his bid for a second term. Labor Day was the president’s last chance to bow out. I expect Biden to win. Get ready for the hardest four years in the White House since Lyndon Johnson lived there, 1965-1969.

That is the implication of a view of American history as a recurring sequence of lengthy political change: breakthroughs, followed by breakups, followed by breakdowns. Over the years, there have been all kinds of cycle theories about U.S. political change. An unusually fully-elaborated version is associated with Yale theorist Stephen Skowronek.

Skowronek distinguishes between what he calls secular time and political time. The latter is time in the system, the medium through which presidents must reckon with commitments their predecessors have made. Secular means the president’s own time in office, for better or worse. Since presidential leadership is what organizers, journalists, and voters care about, secular time is the way our clocks tick.

Thus five major systems, described by their ideological commitments and coalition support, have unfolded in the years since the American Civil War: the presidencies of Abraham Lincoln to Grover Cleveland, 1861- 1897; William McKinley to Herbert Hoover, 1897-1933; Franklin Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson, 1933-1968, Richard Nixon to George H.W. Bush, 1969-93; and Bill Clinton to Joe Biden, 1993-2025.

Underneath all this is the machinery of constitutional democracy, which is manipulated by actors to determine the outcomes: the federal system, with its regional governments; the three branches of national government, with their various checks and balances; the coalitions of interests, old and new, that constantly shift back and forth; and, finally, “presidential definition” in public opinion, a concept more elusive than the rest.

What enables a president to set an agenda that lasts thirty years?

Luck and timing, of course. There may be a sense that “it’s time for a change.” If a candidacy succeeds, gradually choices are made. These may meet with success among voters. If they do, a two-term president’s successors are constrained. Otherwise, a one-term president goes home.

In Clinton’s case, “presidential definition” turned on his decisions to balance the budget, ignore China and to expand NATO to the borders of Russia. Presidents since then have paid less attention to the budget constraint, continued to cooperate with China in varying degrees, but they have continued to attempt to expand NATO, which has led to the war in Ukraine.

Much of this happened on Barack Obama’s watch, when Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, two failed presidential candidates, served successively as secretary of state. Donald Trump’s presidency led to four years of vamping, thanks to his conflicts with both Russian and Ukrainian interests. Then Biden, who as vice president oversaw Ukrainian policy for eight years as vice president, as president promoted his team of advisers and pressed ahead. It is his war to win, or, more likely, to lose.

So, after the thirty years that began with the election of Bill Clinton, Biden is probably a breakdown president,. His age is a problem. There is his relationship with his son Hunter. “Bidenomics” offers little hope of coming to grips with America’s looming fiscal crisis.

What next? Forget about Trump. I expect a traditional Republican candidate to emerge from the embers of Biden’s presidency, as Lincoln emerged from the ashes of James Buchanan’s single term in office, to end the Andrew Jackson-Buchanan system, 1832-1861 and found the modern GOP. Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin, an up-to-date version of former GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney, is the most obvious possibility today, but things will shift around a good deal in the next five years.

By 2028, climate change and fiscal crisis probably will be the central issues, replacing the war in Ukraine, threats to Taiwan and the composition of Trump’s Supreme court. Mitch McConnell, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas will matter less. The rising generations will matter more.

How to follow developments? Continue to read the four great English-language newspapers – The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. The long swings will continue. America will be all right.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com.

David Warsh: Of economics ideas and the power of big business to shape policies

Theater lobby card for the American short comedy film Big Business (1924)

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming, by Nami Oreskes and Erik Conway, was a hard-hitting history in 2010 that catapulted its authors to fame – Oreskes all the way to Harvard University; Conway remained at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech.

Their new book – The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market (Bloomsbury, 2023) – the authors describe as a prequel. In identifying the doubters, it exhibits the same strengths as before. It displays greater weaknesses in establishing the various truths of the matter. It is, however, a page-turner, a powerful narrative, especially if you are already feeling a little paranoid and looking for a good long summer read.

It’s all true, at least as far as it goes. Those three powerful intellects – Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman and Ludwig von Mises – started with unpopular arguments and won big. From the National Electric Light Association and the Liberty League in the Twenties and Thirties, the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Chamber of Commerce in the Fifties and Sixties, to the Federalist Society and the Club for Growth of today, business interests have been spending money and working behind the scenes to boost enthusiasm for markets and to undermine faith in government initiative.

To tell their gripping story of ideas and money, Oreskes and Conway rely on much work done before. Pioneers in this literature include Johan Van Overveldt (The Chicago School: How the University of Chicago Assembled the Thinkers who Revolutionized Economics and Business, 2007); Steven Teles (The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law); 2008); Kim Phillips-Fein, (Invisible Hands: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2009); Jennifer Burns (Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right, 2009); Phillip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe (The Road to Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, 2009); Daniel Rodgers (Age of Fracture, 2011); Nicholas Wapshott (Keynes Hayek: The Clash that Defined Modern Economics, 2011); Angus Burgin (The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression, 2012); Daniel Stedman Jones (Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman, and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics, 2012); Robert Van Horn, Phillip Mirowski and Thomas Stapleford, (Building Chicago Economics: New Perspectives on the History of America’s Most Powerful Economics Program, 2011); Avner Offer, and Gabriel Söderberg (The Nobel Factor: The Prize in Economics, Social Democracy, and the Market Turn, 2016); Lawrence Glickman (Free Enterprise: An American History, 2019); Binyamin Appelbaum (The Economists’ Hour: False Prophets, Free Markets, and the Fracture of Society) 2019); Jennifer Delton (The Industrialists: How the National Association of Manufacturers Shaped American Capitalism, 2020); and Kurt Andersen (Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America a Recent History, 2020). Biographies of Robert Bartley and Roger Ailes remain to be written.

So about those weaknesses? They boil down to this: In The Big Myth you seldom get the other side of the story. Take a fundamental example. Oreskes and Conway assert that “the claim that America was founded on three basic interdependent principles: representative democracy, political freedom, and free enterprise,” cooked up in the Thirties by the National Association of Manufactures for an advertising campaign. This so-called called “Tripod of Freedom” was “fabricated,” Oreskes and Conway maintain; the words free enterprise appear nowhere in the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, they declare. That stipulation amounts to a curious “blind spot,” Harvard historian Luke Menand observed in a lengthy review in The New Yorker. There are mentions of property, though, writes Menand, “and almost every challenge to government interference in the economy rests on the concept of property.” See Adam Smith’s America: How a Scottish Philosopher Became an Icon of American Capitalism (Princeton, 2022), by Glory Liu, for elaboration.

Similarly, the previous Big Myth with which the market fundamentalists and the business allies were contending received little attention. As the industrial revolution gathered pace in the late 19th Century, progressives in the United States preached a gospel of government regulation. Germany’s success in nearly winning World War I received widespread attention. Britain emerged from World War II with a much more socialized economy than before. And in the U.S., government planning was espoused by such intellectuals as James Burnham and Karl Mannheim as the wave of the future.

Finally, The Big Myth largely ignores the experiences of ordinary Americans in the years that it covers. For all the fury that Big Coal mounted against the Tennessee Valley Authority, its dams were built, nevertheless. There is only a single fleeting mention of George Orwell, though his novels Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949) probably influenced far more people than Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom. Paul Samuelson’s textbook explanation of the workings of “the modern mixed economy” dominated Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom tract for forty years and probably still does.

Yet there can be no doubt that there was a disjunction. Oreskes and Conway mention that in the ‘70’s conservative historian George Nash considered that nothing that could be described as a conservative movement in the mid-’40s, that libertarians were a “forlorn minority.” President Harry Truman was reelected in 1948, and Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate Republican, served for eight years after him. Suddenly. in 1964, Republicans nominated libertarian Barry Goldwater. Then came Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

What happened? America’s Vietnam War, for one thing. Globalization for another. Massive migrations occurred in the US, Blacks and Hispanics to the North, businesses to the West and the low-cost South. Civil rights of all sorts revolutions unfolded, at all points of the compass. The composition of Congress and the Supreme Court changed all the while.

In Merchants of Doubt, Oreskes and Conway were on sound ground when making claims about tobacco, acid rain, DDT, the hole in the atmosphere’s ozone layer and greenhouse-gas emissions. These were matters of science, an enterprise devoted to the pursuit of questions in which universal agreement among experts can reasonably hope to be obtained. It was sensible to challenge the reasoning of skeptics in these matters, and to probe the outsized backing they received from those with vested interests. The interpretation of a hundred years of American politics is not science; much of it is not even a topic for proper historians yet. Agreement is reached, if at all, through elections, and elections take time.

Again, take a small matter, the interpretation of “the Reagan Revolution.” Jimmy Carter started it, Oreskes and Conway maintain; Bill Clinton finished it via the “marketization” of the Internet, and most persons have suffered as a result. It is equally common to hear it proclaimed that Reagan presided over an agreement to repair the Social Security system for the next fifty years, ended the Cold War on peaceful terms, and, by accelerating industrial deregulation, ensured on American dominance in a new era of globalization.

In arguments of this sort, EP prefers Spencer Weart’s The Discovery of Global Warming to Merchants of Doubt and Jacob Weisberg In Defense of Government: The Fall and Rise of Public Trust to The Big Myth. But I share Oreskes’ s and Conway’s concerns while searching for opportunities to build more consensus. A century after today’s market fundamentalists began their long argument with Progressive Era enthusiasts for government planning, sunlight remains the best disinfectant.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

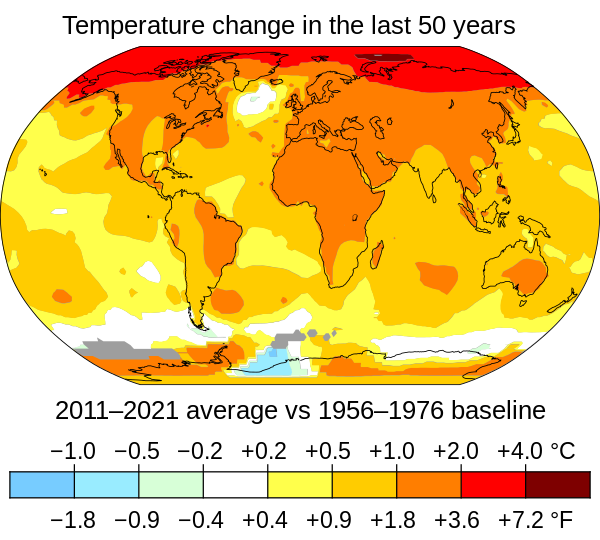

David Warsh: Why I hope that Biden decides, after all, not to run again

Confronting global warming is our greatest challenge.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

What are the chances that Joe Biden will take himself out of the 2024 presidential campaign, perhaps with a Labor Day speech? Not good, based on what I read in the newspapers. Yet I have begun hoping that Biden just might drop out of the race. Here’s why.

It is not because Biden would fail to win re-election if he sticks to his plan to run. He promised to serve as a bridge and he has done that. His takeover of Donald Trump’s Big Talk platform of 2016 seems nearly complete. “Bidenomics,” which boils down to strategic rivalry with China, is the right road for American industry and trade for many years to come.

The problem is that a second term would almost certainly end in disaster, for both Biden and for the United States. The dismal war in Ukraine; the threat of another in Taiwan; the impending fiscal crises of America’s Social Security and medical-insurance programs: these are not problems for a good-hearted 82-year-old man of diminishing mental capacity, much less his fractious team of advisers.

Most of all, there is the challenge of global warming. It seems safe to say that there can no longer be doubt in any quarter that the problem is real. Perhaps this year’s strong demonstration effects were required to galvanize public opinion for action. But what action to take?