Robert Whitcomb: How to Speed Up Infrastructure Repair

An irritated citizenry has blocked a bid by the Pawtucket Red Sox, employing very few people and with a mostly seasonal business, to grab valuable public land and erect, with lots of public money, a stadium in downtown Providence, on Route 195- relocation land. The plan would have involved massive tax breaks for the rich PawSox folks that would have been offset by mostly poorer people’s taxes.

The public is belatedly becoming more skeptical about subsidizing individual businesses. (Now if only they were more skeptical about casinos’ “economic- development’’ claims. Look at the research.)

Perhaps Lifespan will sell its Victory Plating tract to the PawSox. And maybe a for-profit (Tenet?) or “nonprofit’’ (Partners?) hospital chain will buy Lifespan, which faces many challenges. Capitalism churns on!

In any event, the stadium experience is a reminder that we must improve our physical infrastructure, in downtown Providence and around America.

Improved infrastructure will be key to a very promising proposal by a team comprising Baltimore’s Wexford Science & Technology and Boston’s CV Properties LLC for a life-sciences park on some Route 195-relocation acres. This could mean a total of hundreds of well-paying, year-round jobs in Providence at many companies. Tax incentives for this idea have merit. (I’d also rather fill the land slated for a park in the 195 area with other job-and-tax-producing businesses, but that’s politically incorrect.)

The proximity of the Alpert Medical School at Brown University, the Brown School of Public Health, hospitals and a nursing school is a big lure. Also attractive is that Providence costs are lower than in such bio-tech centers as Boston-Cambridge and that the site is on the East Coast’s main street (Route 95, Amtrak and an easy-to-access airport).

Rhode Island’s decrepit bridges and roads are not a lure. Governor Raimondo’s proposal for tolls on trucks (which do 90 percent of the damage to our roads and bridges) to help pay for their repair, and in some cases replacement, should have been enacted last spring. It’s an emergency.

It takes far too long to fix infrastructure, be it transportation, electricity, water supply or other key things. The main impediment is red tape, of which the U.S. has more than other developed nations. That’s why their infrastructure is in much better shape than ours.

Common Good sent me a report detailing the vast cost of the delays in fixing our infrastructure and giving proposals on what to do. It has received bi-partisan applause. But will officials act?

The study focuses on federal regulation, but has much resonance for state policies, too. And, of course, many big projects, including the Route 195-relocation one, heavily involve state and federal laws and regulations.

Among the report’s suggestions:

* Solicit public comment on projects before (my emphasis) formal plans are announced as well as through the review process to cut down on the need to revise so much at the end, but keep windy public meetings to a minimum.

* Designate one (my emphasis) environmental official to determine the scope and adequacy of an environmental review in order to slice away at the extreme layering of the review process. Keep the reports at fewer than 300 pages. The review “should focus on material issues of impact and possible alternatives, not endless details.’’ Most importantly, “Net overall (my emphasis) impact should be the most important finding.’’

* Require all claims challenging a project to be brought within 90 days of issuing federal permits.

* Replace multiple permitting with a “one-stop shop.’’ We desperately need to consolidate the approval process.

Amidst the migrants flooding Europe will be a few ISIS types. That there are far too many migrants for border officials to do thorough background checks on is scary.

Fall’s earlier nightfalls remind us of speeding time. When you’re young, three decades seem close to infinity, now it seems yesterday and tomorrow. I grew up in a house built in 1930, but it seemed ancient. (My four siblings and I did a lot of damage!) Yet in 1960, when I was 13, the full onset of the Depression was only 30 years before. The telescoping of time.

Charles Chieppo: What Do the States Really Owe?

When it comes to getting your arms around just how much states really owe, there is no shortage of moving parts. There's bonded debt, and then there are liabilities for pensions and for other post-employment benefits such as retiree health care.

Dig deeper and you find that states set different periods over which they aim to pay down liabilities and that they assume differing rates of return on investments. Some states use fixed annual payments, but many use a gradually increasing schedule that results in payments being backloaded.

A new report from J.P. Morgan performs an important service by showing how states would stack up if all of these major variables were standardized. The study's author, Michael Cembalest, assumes a 6 percent rate of return on investments, level annual payments and a 30-year term for paying down liabilities.

Despite nearly $1.5 trillion in debts and unfunded retirement obligations, the study finds that, overall, state liabilities don't amount to the kind of national crisis that has often been portrayed. That is, unless you live in one of the states that face some very difficult choices because their debt and retirement costs are at or above a quarter of state revenues.

Cembalest finds that states with a liability-to-revenue ratio of 15 percent or less are in pretty good shape, and 36 states fall into that category. But eight states are in trouble. Given all the attention its pension problems have garnered, it's no surprise that Illinois is the worst, but wealthy Connecticut isn't far behind. Five of the eight (Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky and New Jersey) would have to more than double their annual payments to get their debt and retirement liabilities under control. The other two states on the watch list are Massachusetts and West Virginia.

The 6 percent rate of return Cembalest assumes on state investments is below historical averages, but it represents a much safer strategy than the 7.5-8 percent that most states assume. Such rosy assumptions result in gaping budget holes during tough economic times when states are least able to plug them.

While it might seem to make sense to increase annual retirement-liability payments each year on the assumption that inflation increases payrolls over time, too high a rate of annual escalation results in backloaded contributions that can understate long-term liabilities.

Perhaps as a result of the attention devoted to public-pension costs in recent years, 29 states made their full annual required contribution (ARC) to their pension funds in 2012. But the cost of other post-employment benefits (OPEB) is an even larger burden than pension liabilities in Hawaii and Delaware, and it is equal to pensions in Connecticut, New Jersey and West Virginia.

Despite the magnitude of the problem, just seven states made their full ARC toward paying down OPEB liabilities that year. Montana and Nebraska contributed nothing.

If the J.P. Morgan report is correct, most states have dodged a bullet. But to avoid a future crisis, they must do a better job of both calculating and addressing long-term liabilities. Massachusetts, for example, uses a debt affordability analysis calibrated to ensure that debt-service costs don't exceed 8 percent of budgeted revenue in any future year.

In addition, state taxpayers can no longer shoulder the entire downside risk for pensions. As I have argued before, they should transition to a system under which employees have a choice between defined-contribution and cash-balance plans.

The majority of states that face manageable debt and retirement liabilities can rightfully breathe a sigh of relief. But unless they get more conscientious about long-term liabilities, they won't be so lucky in the future.

Charles Chieppo: New convention center math

Rarely is state government’s dysfunction on display more than in the waning days of a legislative session. This time around, exhibit A is the rush to approve a $1.1 billion expansion of the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center (BCEC) despite enough red flags to fill the quarter-mile-long building.

Apparently the $620 million the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority claims the BCEC and the Hynes Convention Centers pumped into the local economy last year makes it easy to set aside doubts. But a closer look at how the MCCA arrives at that estimate makes you realize why there are no real numbers in the convention industry.

Convention centers are designed to attract people from outside the area who wouldn’t otherwise spend money here. But one thing the industry doesn’t want you do know is that about half of convention attendees — whether in Boston or elsewhere — are generally locals who’d be spending their dollars at a nearby mall if they weren’t eating in a Seaport District restaurant. It’s no accident that the number of hotel room nights generated by the BCEC and the Hynes is less than the number of people who attend events at the facilities; many of the attendees sleep in their own beds at night.

Yet when Pioneer Institute obtained a description of the methodology by which the MCCA derives its economic impact number, we discovered that it includes a “dollars saved” category and assumes “the in-state attendee would have attended the event regardless of location.” Believe it or not, the MCCA actually pretends that every local attendee at a BCEC or Hynes convention would still have gone if it were held in Las Vegas or Orlando, and the authority includes the savings as part of its “economic impact.”

Did that $620 million number just lose a zero?

The economic impact follies are just the latest in a line of troubling revelations about the expansion proposal. First came word that, contrary to MCCA claims, taxpayers would indeed pay a price for expansion. Receipts from taxes that flow into the Convention Center Fund and support the authority could revert to the commonwealth’s general fund once BCEC bonds are paid off in 2034. Expansion of the facility would keep that money flowing to the MCCA until about 2050, siphoning off at least $5 billion from state coffers.

Next we learned that the expansion bill doesn’t require the MCCA to go back to the Legislature if it wants to take more money from the Convention Center Fund. The waiver is akin to a blank check when it comes to the hefty public subsidy that will be needed for the 1,200 to 1,500 room headquarters hotel that is part of the expansion plan.

Finally we learned that the legislation exempts the project from state procurement and public disclosure laws. That means we might never find out how large a subsidy that new hotel will require.

Thankfully, as the Herald recently reported, Senate Bonding Committee Chair Brian Joyce (D-Milton) thinks the BCEC expansion question requires more thought and deliberation. Let’s hope this is one time when lawmakers won’t pass a bill to find out what’s in it.

Charles Chieppo is a senior fellow at Pioneer Institute. He is a former vice chair of the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority.

Chris Powell: Why not elect UConn's president and board instead?

Now that the likely Republican nominee, Tom Foley, has assured state employees that he would follow Governor Malloy's generous policies toward them, there's not much point in having an election for governor. The state employees have already won it by forfeit. But since the University of Connecticut has just decided to push its annual budget up to $1.2 billion, an increase of nearly 5 percent, and to raise tuition by more than 4 percent, it would be good if the state could have an election for the university's president and Board of Trustees.

Yes, as UConn officials complain, state government's direct financial support for the university has been declining and as a result tuition increases are as much a decision by the governor and General Assembly as by the university itself.

But behind the political cover of its champion basketball teams UConn long has been building an empire about which there are many compelling questions.

Salaries at UConn are sometimes so spectacular as to be scandalous, from the president's own, $500,000, to the salaries of various UConn employees who get inconvenient notice from time to time, like the police chief, music department dean, and vice president for publicity who lately have been paid nearly a quarter million dollars, far more than the governor is paid for taking nominal responsibility for the whole of state government.

While in raising its budget the university boasted that it is improving its ratio of teachers to students, it did not detail how many of those teachers will be actually teaching rather than pursuing UConn's longtime objective to become “a great research university,” wherein professors get to do whatever they want and needn't bother with mere undergraduates, whose instruction can be left to graduate assistants, some from abroad with impenetrable accents. The university long has been vague about just how much teaching is being done by exactly whom.

Then there's the UConn Foundation, which lately has been keeping two presidents on its payroll, the outgoing one making $484,000 per year as a sort of retirement gift and the new one enjoying a salary that has not been disclosed, apparently because it would risk more criticism.

In addition, the foundation recently spent $660,000 so the university's president could have not only a mansion in Storrs but also a mansion in Hartford from which she and the university might more easily continue to overawe the governor and state legislators.

That Connecticut knows even this much about the UConn Foundation is only by its permission. The foundation has been exempted from the state's Freedom of Information Act on the grounds that donors might be less generous if the public could find out what they are giving -- information that would involve what they are [ITALICS] getting [END ITALICS] in exchange for their donations, like the dismissal of the university's athletic director three years ago, which happened not long after it was demanded by a big donor who was sore that the athletic director wouldn't heed his advice about the football team.

Two months ago the Senate chairman of the General Assembly's Higher Education Committee, Stephen T. Cassano, D-Manchester, acknowledged UConn's haughtiness, remarking, "We have just as much chance of sitting with the Soviet Union as we do with UConn." Cassano expressed concern about the impending tuition increase and said the university needed to communicate more with the legislature.

But nothing came from that; it was only Cassano's obligatory posturing when he was pressed for comment. He called no hearings. Meanwhile the governor lets UConn do whatever it wants and legislators generally are content if they can have their pictures taken with the basketball players. No one in authority puts any critical question to the university and there's little danger that it will have to answer to anyone soon.

-----

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer in Manchester, Conn.

Don Pesci: The Rock Cats Shuffle

Facing what is certain to be a hard fought gubernatorial campaign, Governor Dannel Malloy vowed that he would not intervene (read: invest state tax money in) a pre-arranged deal between officials in Hartford and the owners of the New Britain Rock Cats to reposition the baseball team in Hartford.

Chris Powell, managing Editor of the Journal Inquirer and the paper’s chief political columnist, noted wryly that any such “investment” on the part of Mr. Malloy would be redundant, since state taxpayers already provide Hartford, as well as other large non-self-sustaining cities in Connecticut, with sufficient funds that more than offset any expenses involved in relocating and housing the team.

The Malloy administration certainly has sufficient experience in providing tax funds to a number of companies in Connecticut that have moved from one town in the state to another, but this time, perhaps because of the proximity of an election, Mr. Malloy has turned his face to the wall. He had already gone on record as promising no new taxes, no union giveaways and no reductions in services. Any tax money doled out to Hartford, a one-party Democratic basket case, to facilitate the Rock Cats’ move from New Britain to Hartford would, considering the campaign pledges made by Mr. Malloy, have been politically awkward.

The crowd that turned out at the Town Meeting in Hartford to oppose the Rock Cats shuffle was not concerned with the political futures of those One Party Town politicians who brokered the deal months before it was announced as a fait accompli by Hartford Mayor Pedro Segarra. Opposition to the back- room deal was vigorous – and poetic.

Hartford resident Chris Brown stepped before the microphone and said:

In a starling announcement on the sunny fourth of June, From left field came a surprise that afternoon. With dicey-looking figures and mathematical wiggle room, We saw the latest road map to efficient fiscal doom. The numbers are inflated, optimistic fuzzy math, With details twice as blurry as a fuzzy photograph. If the goal’s creating jobs, I propose a better path. Make jobs of things we use in Hartford every day, Like my wondrous local library, underfunded, overfilled, Like repairing the streets and sidewalks that are crumbling away … These lower cost investments in the things you might find dull Will be longer term solutions to our economic lull. They are all more shovel-ready than a steaming load of bull.

Mr. Brown’s poetry recital was interrupted twice by raucous applause. People in the audience were resisting the move for two reasons: 1) They felt that the priorities of the city fathers, all Democrats, were woefully misplaced. Hartford’s real needs would not be met by the relocation to the city of a baseball team; and 2) Those who arranged the deal months earlier had not consulted them concerning the move.

"People talk a lot about the declining faith in government," said Joshua King, who lives on Broad Street. "This is why. This is it."

"When the mayor came on, one of his biggest words was transparency," said Evelyn Richardson of Enfield Street. "How do you hold 18 months of [secret] meetings and call that transparency?"

Mayor Pedro Segarra issued a response through a spokeswoman: "We have understood from the beginning that this project would require public discussion, participation and dialogue. Just like tonight, there will be many opportunities to learn more about how this revitalization will be an asset to the community for years to come."

Mr. Brown touched most of these points in his poem: Public discussion should precede, not follow, major decisions. Without pre-discussion the “government of the people by the people and for the people” is thrown to the three winds. Mr. Segarra wears his arrogance well. To say in the face of such heated resistance “there will be many opportunities to learn more about how this revitalization will be an asset to the community for years to come" is to say – the only role the public may play in matters of this kind is to hear and accept supinely the decisions that have been made for you by your betters.

This is the usual posture of most political leaders in one-party political operations -- countries, states, towns or, for that matter, families ruled by stiff-necked autocrats.

The real problem with Hartford is that it is suffering all the ills of a one party autocracy. Always and everywhere in history, the autocrat, the patron, the Jefe, is interested chiefly in maintaining his status through the abject obedience of his subjects, who receive benefits dispensed by the one party operation without their participation or consultation. Real democracy upsets his carefully constructed apple cart.

Jefe knows best.

Don Pesci is a writer who lives in Vernon E-mail: donpesci@att.net

“The Rule of Nobody: Saving America From Dead Laws and Broken Government,” is a well-named collection of proposed new amendments to the U.S. Constitution that he calls the “Bill of Responsibilities.”

In the appendix of Philip K. Howard’s new book,

“The Rule of Nobody: Saving America From Dead Laws and Broken Government,” is a well-named collection of proposed new amendments to the U.S. Constitution that he calls the “Bill of Responsibilities.”

I over-summarize them here; read the book. Mr. Howard is an engaging writer, using stories (some grimly funny) to get across his strong prescriptions.

Mr. Howard proposes amendments to: “sunset” old laws and regulations; give the president power to far more effectively manage the executive branch — including line-item vetoes and expanded discretion to hire and fire and reorganize operations, all subject to being overridden by a majority of each house of Congress — and widen judges’ power to dismiss unreasonable lawsuits.

Finally, he recommends an amendment to create a “Council of Citizens” as an advisory body to make recommendations on how to make government more responsive to the public’s needs. This reminds me of the Hoover commissions on government reorganization of the late 1940s and the ’50s, named after Herbert Hoover, who chaired them. The composition of this council would be very federalist, with members chosen “by and from a Nominating Council composed of two nominees by each governor of a state.” The idea is to push along the ideas represented by the other new amendments. This is intriguing but the nomination process could get caught in political sludge.

The phrase “Bill of Responsibilities” gets to the heart of what Mr. Howard is saying throughout his book: that we have become so tangled up in laws and regulations that it’s often impossible to exercise authority and take responsibility — the avoidance of which, I would add, is attractive to many people, just as long as they continue to have the perks of their positions. As a result, it’s tougher and tougher to get things done, at the local, state and federal levels, whether it is fixing a bridge, creating a health-care system whose benefits are commensurate with its vast cost, or firing an incompetent bureaucrat.

Admiral Chester Nimitz said during World War II, “When in command, command.” President Truman said of the prospect of Dwight Eisenhower as president: “He’ll sit here, and he’ll say ‘Do this! Do that!’ And nothing will happen. Poor Ike. It won’t be a bit like the Army. He’ll find it very frustrating.” Well, Eisenhower turned out to be a pretty effective president but Truman was fairly accurate: It has always been hard to make government work, and in many ways it’s harder now than 60 years ago because of the accretion of laws and regulations, many of which should have been eliminated or streamlined long ago. A law or a regulation cannot cover every eventuality, Mr. Howard writes: You need judgment and common sense. Fewer laws and more decisions, please!

The problems that Philip Howard tackles remind me of the growing dominance of process over content (or maybe call it substance). You see this in daily life with the increasing time demanded to keep up with endlessly updated computer programs (planned obsolescence!), and the hours needed to fill out tax returns and insurance forms.

Meanwhile, the European Court of Justice has issued an advisory judgment that European Union residents have the right in certain circumstances to make search engines remove links to personal information that people think damages them. It’s “the right to be forgotten,” a cousin of Americans’ famous, if informal, “right to be left alone.”

This will be very difficult to enforce, given the vast complexity of the Web. But I like the idea of taking down the arrogance of Google, et al., a few notches. You don’t have to be much of a “public figure” to be the object of scurrilous inaccurate attacks on the Internet for which the likes of Google wrongly take no responsibility. In the Digital Age your good name can be instantly destroyed on the screen.

The court supported exceptions for “public figures,” especially politicians. But that’s very tricky: Almost anyone can become a “public figure” on the Internet. And is it fair to exclude politicians, etc., from such protection from attacks? Whatever, the European case at least raises the issue of responsibility for content, which the search-engine companies, most notably Google, have tended to avoid while raking in billions of dollars.

***

A college “commencement” is a strange term because it seems much more of an ending, as emphasized by the dirge-like “Pomp and Circumstance.” Sadder is that so many colleges, supposedly refuges of the free exchange of ideas, surrender to demands for censorship by “activists” to block commencement speeches by people (usually with comparatively “conservative” views) whose opinions they don’t like. Cowardly college chiefs fail to take responsibility for protecting one of their central missions.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), a former editor of these pages, is an editor, writer, management consultant at Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com). and a fellow at Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy.

Crows' business model; river town

Crows, which are highly intelligent, if often associated with death, have a very effective business model as scavengers. Indeed, being a good scavenger of things and ideas seems essential for thelong-term success of most of us. (A successful investor is a particularly good scavenger -- an outstanding opportunist.)

"Two Crows,'' by JAMES REED, in his show at Gallery19, in Essex, Conn., through June 3o.

Crows, which are highly intelligent, if often associated with death, have a very effective business model as scavengers. Indeed, being a good scavenger of things and ideas seems essential for the long-term success of most of us. (A successful investor is a particularly good scavenger -- an outstanding opportunist.)

When I was a kid living on thepre-environmentalist coast, seagulls were protected because they cleaned up the garbage left in the open. They did a particularly fine job on the remnants of beach picnics. Crows do the same thing and swiftly consume roadkill, too.

Essex, by the way, is a beautiful town on the Connecticut River, one of several beautiful communities in its area. New England is not famous for its big rivers, of which the Connecticut is the only one, and doesn't have many of what you would call "river towns'' in, say, a Midwestern or Southern sense.

But the Connecticut looks pretty big in the southern Nutmeg State and Essex is definitely a river town, with all that implies about water-borne transportation, commerce and culture in general.

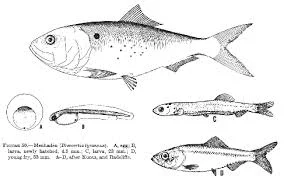

Peter Baker: The centrality of menhaden

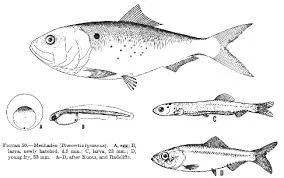

Fisheries managers for the Atlantic Coast states face an important decision May 5 about what is sometimes called the most important fish in the sea: Atlantic menhaden. Officials could increase the allowable catch to appease the East Coast’s largest fishing industry. Or they could begin to manage this forage species in a way that protects fish, seabirds and whales, as well as the interests of the people who care about and depend on those animals from Florida to Maine.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission is under pressure from the menhaden fishing industry to raise the catch quota put in place in 2012. Some menhaden are used for bait, but roughly 80 percent of the catch is allocated to a single company that pulverizes and renders the fish into animal feed and oil. The industry points to signs of improvement in a menhaden stock assessment released in January as evidence to support an increase in the catch.

But menhaden matter as more than just ingredients in industrial products; they are an immensely valuable public resource. Schools of menhaden form a crucial part of the coastal food web, as the fish gulp plankton, composed of tiny plants and animals, and turn it into fat and protein that other animals then consume. An array of wildlife, including striped bass, humpback whales and ospreys, thrives when menhaden are plentiful and suffers when they are not.

Unfortunately, the proposals to increase the menhaden quota don’t take into account the needs of these predators. Allowing hundreds of millions of menhaden to be taken from the ocean without understanding the ecological impact would be risky and could undermine conservation efforts for many species. There’s a safer way to proceed.

More than a decade ago, the commissioners set a goal to “protect and maintain the important ecological role Atlantic menhaden play along the coast.” Now they have the opportunity to do just that, by making sure the catch limit for 2015 also accounts for the menhaden that marine predators rely on. The commissioners could also initiate an amendment to their management plan for Atlantic menhaden in order to bring a modern, big-picture approach to future decisions about this fish and its place in the ocean food web.

Appropriately set population targets would make sure that those that prey on menhaden have plenty to eat.

Although the most recent assessment of menhaden offered some good news, it raised concerns in other aspects. It indicated that the total biomass — the estimated combined weight of all fish — has increased, but also found that the actual abundance — the estimated number of fish — remains near historic lows. The menhaden population is still in need of conservation and hasn’t recovered throughout its historic range, from Maine to Florida.

The continuing lack of abundance is arguably more critical for predators such as striped bass, a fish that is highly prized by anglers but declining in numbers. The commissioners recently made a difficult decision to reduce the striped bass catch in order to address this coast-wide problem.

These and other important predator fish need abundant food if they are going to recover and thrive.

This gallery of images gives an idea of what we can expect to see when we realize an ample supply of menhaden in the water: humpback whales in New York’s waters, striped bass on fishermen’s lines, and ospreys and bald eagles feasting in bays. These are more than just pretty pictures. They are snapshots of a healthy ecosystem that supports coastal residents and businesses, such as charter boat captains and ecotourism operators.

Peter Baker directs ocean conservation in the Northeast for The Pew Charitable Trusts.

US Capitalism Seems to be Taking Another Turn

US capitalism seems to be taking another turn. The Old Normal (Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time Is Different) was the expectation that, even after a serious banking crisis, growth would resume its long-term annual trend of 2.0 percent in five years or so. The New Normal says, “Forget the trend.”

US capitalism seems to be taking another turn. The Old Normal (Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time Is Different) was the expectation that, even after a serious banking crisis, growth would resume its long-term annual trend of 2.0 percent in five years or so. The New Normal says, “Forget the trend.”

Robert Gordon, of Northwestern University, and Lawrence Summers, of Harvard University, expect slow growth for decades, thanks to various “headwinds,” or constraints on potential output (Gordon); or insufficient demand, stemming from a savings glut (Summers).

A lively discussion of these bold new claims is taking place, so far mainly on blogs, here,here, and here, for example. Soon enough such considerations will impinge on official forecasts, Federal Reserve Board policy, and, naturally, on asset markets. That’s bad news, especially for the bottom 99 percent of the income distribution, where, according to Gordon, growth will be least of all.

It’s always possible the current path it will be altered somehow: a major new invention, an unexpected war, a plague. But at the moment much of this seems already to be written in the cards of growth accounting.

The debate over GDP growth has put me in mind of a favorite book. I don’t mean Diane Coyle’s GDP: A Brief but Affectionate Portrait (Princeton, 2014), though her essay certainly makes very good reading in the present circumstances. GDP is a narrative of activity deemed to be “economic success,” she writes, so it is no surprise that the measure’s primacy should be challenged by those who see it as a symbol “of what’s gone wrong with the capitalist market economy.” She writes,

For example, environmentalists believe it leads to an overemphasis on growth at the expense of the planet, “happiness” advocates think it needs to be replaced with indicators of genuine well-being, and activists… argue that a focus on GDP has disguised inequality and social disharmony.”

Instead, the book I mean is Citizenship and Social Class (Cambridge, 1950) by Thomas Humphrey Marshall, of the London School of Economics, a noted sociologist of his day (he died in 1981.) In 1950 Karl Marx loomed somewhat larger than he does today. By “social class,” I think Marshall meant something like what we call “capitalism” in the present day – or, in shorthand, GDP. Here’s a key excerpt, courtesy of W.W. Norton and J. Bradford DeLong.

The concept of citizenship had been evolving in England since at least the late seventeenth century, Marshall wrote, which meant that the growth of citizenship coincided with the rise of capitalism in that nation. The concepts seemed in near-total opposition. Capitalism was all about inequality, the creation of new classes. Citizenship bestowed equal status on all members of the community, rich and poor alike. Capitalism was about creating new classes. Citizenship was about class-abatement.

Were they related? Certainly rights seemed to have grown hand-in-hand with GDP (starting long before there was any such statistical index of capitalism). Sometimes citizenship advanced in alliance with economic growth, other times in opposition.

This political narrative is very well known – far better than the narrative of, say, the Industrial Revolution. Civil rights, those associated with personal liberty, were established mostly in the eighteenth century, by a series of democratic revolutions; political rights in the nineteenth; social rights in the twentieth. Marshall described them thus:

[Civil rights include] freedom of speech, thought and faith, the right to own property and to conclude valid contracts, and the right to justice. The last is of a different order from the others, because it is the right to defend and assert all one’s rights on terms of equality with others and by due process of law. This shows us that the institutions most directly associated with civil rights are the courts of justice.

By the politica1element I mean the right to participate in the exercise of political power, as a member of a body invested with political authority or as an elector of the members of such a body. The corresponding institutions are parliament and councils of 1ocal government.

By the social element I mean the whole range from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the fuIl in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society. The institutions most closely connected with it are the educational system and the social services.

In 1950 Britain, social rights had to do with extending the welfare state. It seems to me that the second half of the century had to do with bringing economic rights within the meaning of the term, especially in nations formerly deemed to have been socialist. Thrashing out the balance between the right to participate in markets and to share in their fruits, against non-market rights to education, health care, lifetime employment and retirement income, seems to have been what much of the shouting of the last fifty years has been about – in slightly different ways, in the First, Second and Third Worlds (unless, of course, you think that the broadening of the meaning of citizenship was finally settled, once and for all, sometime in the mid-century.

On this (admittedly idiosyncratic) argument, it seems to me that citizenship in the twenty-first century is likely to have to do with the extension of environmental rights to an ever-increasing community of citizens – not just clean air and clear water, which is where the movement began, but the rights to a temperate and at most slowly changing climate; relatively stable borders; and a thoughtfully managed biota.

Now here’s the thing: for the last three hundred and fifty years or so, the battle for expanded rights has led the way. We make our wish list in the political sphere; growth follows in its train. At the moment the top item on the list probably has to do with curbing slowing, then managing climate change. This is not just a matter of “climate week,” the demonstrations in New York, or the UN preparations there for next year’s conference in Paris. Businesses all over the world for years have been incorporating reduced carbon emissions in their spending decisions.

Eventually we can be expected to change the definition of economic success – that is, change the calculation of growth in the GDP – to include the expense of the maintenance of the atmosphere. (Solid waste and water pollution can come later.) In a recent article in Science by Nicholas Muller, of Middlebury College, a faculty research fellow of the National Bureau of Economic Research, showed how such adjustments would increase GDP growth, not diminish it, in periods when the air pollution intensity of output was decreasing — estimated gross external damages (GED) from greenhouse gases fell by half in the US, from 6.4 percent to 3.2 percent of GDP, between 1999 and 2008

In the meantime, it is hard to know how much slow GDP growth may eventually be interpreted as measurement error. Northwestern’s Gordon acknowledges as much. He writes,

… GDP has always been understated. Henry Ford reduced the price of his Model T from $900 in 1910 to $265 in 1923 while improving its quality. Yet autos were not included in the CPI until 1935. Think of what GDP misses: the value of the transition from gas lights, that produced dim light and pollution and were a fire hazard, to much brighter electric lights turned on by the flick of a switch; the elevator that bypassed flights of stairs; the electric subway that could travel at 40mph compared to the 5mph of the horse-drawn streetcar; the replacement of the urban horse by the motor vehicle that emitted no manure; the end of disgusting jobs of human beings required to remove the manure; the networking of the home between 1870 and 1940 by five new types of connections (electricity, telephone, gas, water, and sewer); the invention of mass marketing through the department store and mail order catalogue; and the development of the American South made possible by the invention of air conditioning. Perhaps the most important omission from real GDP was the conquest of infant mortality, which by one estimate added more unmeasured value to GDP in the 20th century, particularly in its first half, than all measured consumption..

In other words, the New Normal is going to take some getting used-to. Capitalism in the twenty-first century is obviously going to be different from capitalism in the twentieth century. More fundamentally, so, too, the rights of humankind.