Elisabeth Rosenthal: Primary- care crisis intensifies

These measurements of health-care service levels for specific areas of the U.S. came out in June 2020 through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

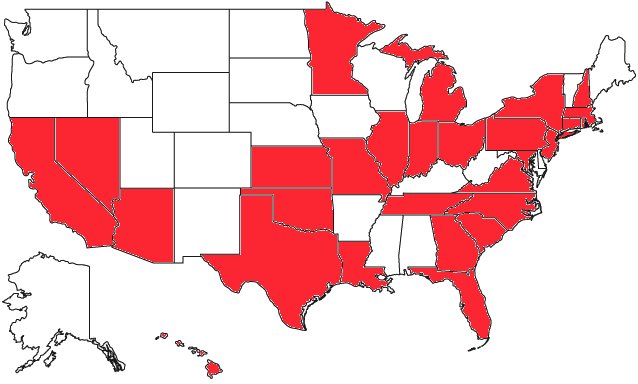

States in red have Rhode Island-based CVS’s Minute Clinics, which are cutting into traditional primary-care practices.

“We have a specialty-driven system. Primary care is seen as a thankless, undesirable backwater.”

— Michael L. Barnett, M.D., health-systems researcher and primary-care physician in the Harvard Medical School system

I’ve been receiving an escalating stream of panicked emails from people telling me their longtime physician was retiring, was no longer taking their insurance, or had gone concierge and would no longer see them unless they ponied up a hefty annual fee. They have said that they couldn’t find another primary-care doctor who could take them on or who offered a new-patient appointment sooner than months away.

Their individual stories reflect a larger reality: American physicians have been abandoning traditional primary- care practice — internal and family medicine — in large numbers. Those who remain are working fewer hours. And fewer medical students are choosing a field that once attracted some of the best and brightest because of its diagnostic challenges and the emotional gratification of deep relationships with patients.

The percentage of U.S. doctors in adult primary care has been declining for years and is now about 25 percent — a tipping point beyond which many Americans won’t be able to find a family doctor at all.

Already, more than 100 million Americans don’t have usual access to primary care, a number that has nearly doubled since 2014. One reason our coronavirus vaccination rates were low compared with those in countries such as China, France, and Japan could be because so many of us no longer regularly see a familiar doctor we trust.

Another telling statistic: In 1980, 62 percent of doctor’s visits for adults 65 and older were for primary care and 38 percent were for specialists, according to Michael L. Barnett, a health-systems researcher and primary- care doctor in the Harvard Medical School system. By 2013, that ratio had exactly flipped and has likely “only gotten worse,” he said, noting sadly: “We have a specialty-driven system. Primary care is seen as a thankless, undesirable backwater.” That’s “tragic,” in his words — studies show that a strong foundation of primary care yields better health outcomes overall, greater equity in health-care access, and lower per-capita health costs.

One explanation for the disappearing primary-care doctor is financial. The payment structure in the U.S. health system has long rewarded surgeries and procedures while shortchanging the diagnostic, prescriptive and preventive work that is the province of primary care. Furthermore, the traditionally independent doctors in this field have little power to negotiate sustainable payments with the mammoth insurers in the U.S. market.

Faced with this situation, many independent primary-care doctors have sold their practices to health systems or commercial management chains (some private-equity-owned) so that, today, three-quarters of doctors are now employees of those outfits.

One of them was Bob Morrow, who practiced for decades in the Bronx. For a typical visit, he was most recently paid about $80 if the patient had Medicare, with its fixed-fee schedule. Commercial insurers paid significantly less. He just wasn’t making enough to pay the bills, which included salaries of three employees, including a nurse practitioner. “I tried not to pay too much attention to money for four or five years — to keep my eye on my patients and not the bottom line,” he said by phone from his former office, as workers carted away old charts for shredding.

He finally gave up and sold his practice last year to a company that took over scheduling, billing and negotiations with insurers. It agreed to pay him a salary and to provide support staff as well as supplies and equipment.

The outcome: Calls to his office were routed to a call center overseas, and patients with questions or complaining of symptoms were often directed to a nearby urgent care center owned by the company — which is typically more expensive than an office visit. His office staff was replaced by a skeleton crew that didn’t include a nurse or skilled worker to take blood pressure or handle requests for prescription refills. He was booked with patients every eight to 10 minutes.

He discovered that the company was calling some patients and recommending expensive tests — such as vascular studies or an abdominal ultrasound — that he did not believe they needed.

He retired in January. “I couldn’t stand it,” he said. “It wasn’t how I was taught to practice.”

Of course, not every practice sale ends with such unhappy results, and some work out well.

But the dispirited feeling that drives doctors away from primary care has to do with far more than money. It’s a lack of respect for nonspecialists. It’s the rising pressure to see and bill more patients: Employed doctors often coordinate the care of as many as 2,000 people, many of whom have multiple problems.

And it’s the lack of assistance. Profitable centers such as orthopedic and gastroenterology clinics usually have a phalanx of support staff. Primary-care clinics run close to the bone.

“You are squeezed from all sides,” said Barnett.

Many ventures are rushing in to fill the primary-care gap. There had been hope that nurse practitioners and physician assistants might help fill some holes, but data shows that they, too, increasingly favor specialty practice. Meanwhile, urgent-care clinics are popping up like mushrooms. So are primary-care chains such as One Medical, now owned by Amazon. Dollar General, Walmart, Target, CVS Health and Walgreens have opened “retail clinics” in their stores.

Rapid-fire visits with a rotating cast of doctors, nurses, or physician assistants might be fine for a sprained ankle or strep throat. But they will not replace a physician who tells you to get preventive tests and keeps tabs on your blood pressure and cholesterol — the doctor who knows your health history and has the time to figure out whether the pain in your shoulder is from your basketball game, an aneurysm, or a clogged artery in your heart.

Some relatively simple solutions are available, if we care enough about supporting this foundational part of a good medical system. Hospitals and commercial groups could invest some of the money they earn by replacing hips and knees to support primary care staffing; giving these doctors more face time with their patients would be good for their customers’ health and loyalty if not (always) the bottom line.

Reimbursement for primary-care visits could be increased to reflect their value — perhaps by enacting a national primary care fee schedule, so these doctors won’t have to butt heads with insurers. And policymakers could consider forgiving the medical school debt of doctors who choose primary care as a profession.

They deserve support that allows them to do what they were trained to do: diagnosing, treating, and getting to know their patients.

The United States already ranks last among wealthy countries in certain health outcomes. The average life span in America is decreasing, even as it increases in many other countries. If we fail to address the primary care shortage, our country’s health will be even worse for it.

Elisabeth Rosenthal is a KFF Health News reporter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal: erosenthal@kff.org, @RosenthalHealth