From Kaiser Health News

Dr. Megan Ranney, of Brown University, has learned a lot about COVID-19 since she began treating patients with the disease in the emergency department in February.

But there’s one question that she still can’t answer: What makes some patients so much sicker than others?

Advancing age and underlying medical problems explain only part of the phenomenon, said Ranney, who has seen patients of similar age, background and health status follow wildly different trajectories.

“Why does one 40-year-old get really sick and another one not even need to be admitted?” asked Ranney, an associate professor of emergency medicine at Brown.

In some cases, provocative new research shows, some people — men in particular — succumb because their immune systems are hit by friendly fire. Researchers hope the finding will help them develop targeted therapies for these patients.

In an international study in Science, 10 percent of nearly 1,000 COVID patients who developed life-threatening pneumonia had antibodies that disable key immune system proteins called interferons. These antibodies — known as autoantibodies because they attack the body itself — were not found at all in 663 people with mild or asymptomatic COVID infections. Only four of 1,227 healthy individuals had the autoantibodies. The study, published on Oct. 23, was led by the COVID Human Genetic Effort, which includes 200 research centers in 40 countries.

“This is one of the most important things we’ve learned about the immune system since the start of the pandemic,” said Dr. Eric Topol, executive vice president for research at Scripps Research, in San Diego, who was not involved in the new study. “This is a breakthrough finding.”

In a second Science study by the same team, authors found that an additional 3.5 percent of critically ill patients had mutations in genes that control the interferons involved in fighting viruses. Given that the body has 500 to 600 of these genes, it’s possible researchers will find more mutations, said Qian Zhang, lead author of the second study.

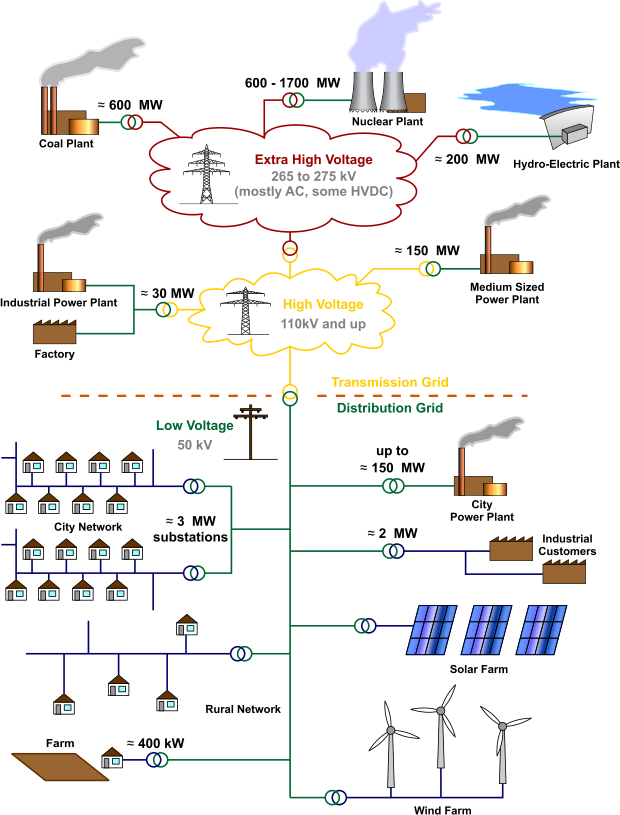

Interferons serve as the body’s first line of defense against infection, sounding the alarm and activating an army of virus-fighting genes, said virologist Angela Rasmussen, an associate research scientist at the Center of Infection and Immunity at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

“Interferons are like a fire alarm and a sprinkler system all in one,” said Rasmussen, who wasn’t involved in the new studies.

Lab studies show interferons are suppressed in some people with COVID-19, perhaps by the virus itself.

Interferons are particularly important for protecting the body against new viruses, such as the coronavirus, which the body has never encountered, said Zhang, a researcher at Rockefeller University’s St. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases.

When infected with the novel coronavirus, “your body should have alarms ringing everywhere,” said Zhang. “If you don’t get the alarm out, you could have viruses everywhere in large numbers.”

Significantly, patients didn’t make autoantibodies in response to the virus. Instead, they appeared to have had them before the pandemic even began, said Paul Bastard, the antibody study’s lead author, also a researcher at Rockefeller University.

For reasons that researchers don’t understand, the autoantibodies never caused a problem until patients were infected with COVID-19, Bastard said. Somehow, the novel coronavirus, or the immune response it triggered, appears to have set them in motion.

“Before COVID, their condition was silent,” Bastard said. “Most of them hadn’t gotten sick before.”

Bastard said he now wonders whether autoantibodies against interferon also increase the risk from other viruses, such as influenza. Among patients in his study, “some of them had gotten flu in the past, and we’re looking to see if the autoantibodies could have had an effect on flu.”

Scientists have long known that viruses and the immune system compete in a sort of arms race, with viruses evolving ways to evade the immune system and even suppress its response, said Sabra Klein, a professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Antibodies are usually the heroes of the immune system, defending the body against viruses and other threats. But sometimes, in a phenomenon known as autoimmune disease, the immune system appears confused and creates autoantibodies. This occurs in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, when antibodies attack the joints, and Type 1 diabetes, in which the immune system attacks insulin-producing cells in the pancreas.

Although doctors don’t know the exact causes of autoimmune disease, they’ve observed that the conditions often occur after a viral infection. Autoimmune diseases are more common as people age.

In yet another unexpected finding, 94 percent of patients in the study with these autoantibodies were men. About 12.5 percent of men with life-threatening COVID pneumonia had autoantibodies against interferon, compared with 2.6 percent of women.

That was unexpected, given that autoimmune disease is far more common in women, Klein said.

“I’ve been studying sex differences in viral infections for 22 years, and I don’t think anybody who studies autoantibodies thought this would be a risk factor for COVID-19,” Klein said.

The study might help explain why men are more likely than women to become critically ill with COVID-19 and die, Klein said.

“You see significantly more men dying in their 30s, not just in their 80s,” she said.

Akiko Iwasaki, a professor of immunobiology at the Yale School of Medicine, noted that several genes involved in the immune system’s response to viruses are on the X chromosome.

Women have two copies of this chromosome — along with two copies of each gene. That gives women a backup in case one copy of a gene becomes defective, Iwasaki said.

Men, however, have only one copy of the X chromosome. So if there is a defect or harmful gene on the X chromosome, they have no other copy of that gene to correct the problem, Iwasaki said.

Bastard noted that one woman in the study who developed autoantibodies has a rare genetic condition in which she has only one X chromosome.

Scientists have struggled to explain why men have a higher risk of hospitalization and death from COVID-19. When the disease first appeared in China, experts speculated that men suffered more from the virus because they are much more likely to smoke than Chinese women.

Researchers quickly noticed that men in Spain were also more likely to die of COVID-19, however, even though men and women there smoke at about the same rate, Klein said.

Experts have hypothesized that men might be put at higher risk by being less likely to wear masks in public than women and more likely to delay seeking medical care, Klein said.

But behavioral differences between men and women provide only part of the answer. Scientists say it’s possible that the hormone estrogen may somehow protect women, while testosterone may put men at greater risk. Interestingly, recent studies have found that obesity poses a much greater risk to men with COVID-19 than to women, Klein said.

Yet women have their own form of suffering from COVID-19.

Studies show women are four times more likely to experience long-term COVID symptoms, lasting weeks or months, including fatigue, weakness and a kind of mental confusion known as “brain fog,” Klein noted.

As women, “maybe we survive it and are less likely to die, but then we have all these long-term complications,” she said.

After reading the studies, Klein said, she would like to learn whether patients who become severely ill from other viruses, such as influenza, also harbor genes or antibodies that disable interferon.

“There’s no evidence for this in flu,” Klein said. “But we haven’t looked. Through COVID-19, we may have uncovered a very novel mechanism of disease, which we could find is present in a number of diseases.”

To be sure, scientists say that the new study solves only part of the mystery of why patient outcomes can vary so greatly.

Researchers say it’s possible that some patients are protected by past exposure to other coronaviruses. Patients who get very sick also may have inhaled higher doses of the virus, such as from repeated exposure to infected co-workers.

Although doctors have looked for links between disease outcomes and blood type, studies have produced conflicting results.

Screening patients for autoantibodies against interferons could help predict which patients are more likely to become very sick, said Bastard, who is also affiliated with the Necker Hospital for Sick Children, in Paris. Testing takes about two days. Hospitals in Paris can now screen patients on request from a doctor, he said.

Although only 10 percent of patients with life-threatening COVID-19 have autoantibodies, “I think we should give the test to everyone who is admitted,” Bastard said. Otherwise, “we wouldn’t know who is at risk for a severe form of the disease.”

Bastard said he hopes his findings will lead to new therapies that save lives. He notes that the body manufactures many types of interferons. Giving these patients a different type of interferon — one not disabled by their genes or autoantibodies — might help them fight off the virus.

In fact, a pilot study of 98 patients published Thursday in the Lancet Respiratory Medicine journal found benefits from an inhaled form of interferon. In the industry-funded British study, hospitalized COVID patients randomly assigned to receive interferon beta-1a were more than twice as likely as others to recover enough to resume their regular activities.

Researchers need to confirm these findings in a much larger study, said Dr. Nathan Peiffer-Smadja, a researcher at Imperial College London who was not involved in the study but wrote an accompanying editorial. Future studies should test patients’ blood for genetic mutations and autoantibodies against interferon, to see if they respond differently than others.

Peiffer-Smadja notes that inhaled interferon may work better than an injected form of the drug because it’s delivered directly to the lungs. While injected versions of interferon have been used for years to treat other diseases, the inhaled version is still experimental and not commercially available.

And doctors should be cautious about interferon for now, because a study led by the World Health Organization found no benefit to an injected form of the drug in COVID patients, Peiffer-Smadja said. In fact, there was a trend toward higher mortality rates in patients given interferon, although this finding could have been due to chance. Giving interferon later in the course of disease could encourage a destructive immune overreaction called a cytokine storm, in which the immune system does more damage than the virus.

Around the world, scientists have launched more than 100 clinical trials of interferons, according to clinicaltrials.gov, a database of research studies from the National Institutes of Health.

Until larger studies are completed, doctors say, Bastard’s findings are unlikely to change how they treat COVID-19.

Dr. Lewis Kaplan, president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, said he treats patients according to their symptoms, not their risk factors.

“If you are a little sick, you get treated with a little bit of care,” Kaplan said. “You are really sick, you get a lot of care. But if a COVID patient comes in with hypertension, diabetes and obesity, we don’t say, ‘They have risk factors. Let’s put them in the ICU.’’

Liz Szabo is a reporter for Kaiser Health News

Liz Szabo: lszabo@kff.org, @LizSzabo