Frank Carini: The brazen and well-financed disinformation campaign of the anti-wind-farm crowd

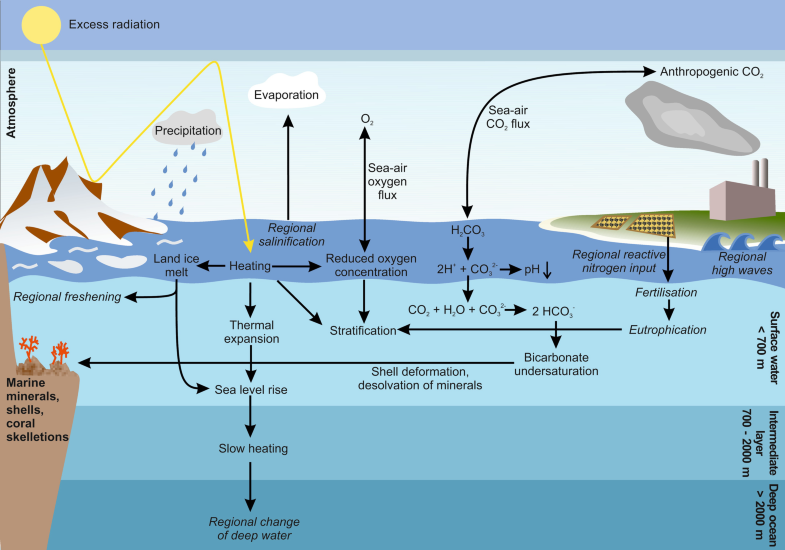

Overview of climatic changes caused by burning fossil fuel and their effects on the ocean. Regional effects are displayed in italics.

Oil spill covering kelp.

The anti-wind mob chums the waters with red herring. The conspiracy theorists continue to hide behind critically endangered North Atlantic right whales to spin tales about offshore wind. Their faux concern is nauseating.

When it comes to the real threats to the 350 or so North Atlantic right whales left on the planet — entanglements with fishing gear and strikes with ships — the mob’s ranting and raving goes largely silent, and my stomach turns.

These self-proclaimed pro-whale warriors only care about the lives of these majestic marine mammals when they fit into their manufactured hysteria about offshore wind.

Among those spreading the mob’s propaganda are southern New England firebrand Lisa Quattrocki Knight, president of Green Oceans, and Constance Gee, a Westport, Mass., resident and Green Oceans member; Lisa Linowes, executive director of the Industrial Wind Action Group Corp, also known as The WindAction Group; Protect Our Coast New Jersey; and blogger Frank Haggerty, a blowhole of offshore wind misinformation.

Their bluster is either funded by the fossil-fuel industry and/or they are wealthy coastal property owners more concerned that their ocean views will be ruined by a different type of energy infrastructure. Either way, the lives of whales, dolphins, birds, and humans living near polluting fossil-fuel operations don’t matter.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Cynthia Drummond: Nurture New England’s native plants

Blossoms of mountain laurel, a common shrub in southern New England

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A story in a recent issue of a national gardening magazine extolled the benefits of “naturalistic garden design,” a less constrained landscape that features native plants grouped in ecologically compatible communities.

The reader was encouraged to look for inspiration in the local ecosystem and to “suspend fussiness” to develop a wilder, more resilient garden that is in tune with the surrounding natural landscape.

Magazine articles about native plants indicate their growing acceptance as garden plants, but because they have co-evolved over thousands of years with native insect and bird species, these plants play a much more critical role.

David Gregg, director of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, described native plants as central components in the evolution of the Rhode Island ecosystem.“They’re the environment and context in which all the other animals in our plants in our area evolved,” he said.

“So, the bees’ tongues are the right length to get the nectar from the flowers. The birds can eat the caterpillars that that eat those plants. The soil microbes are such that those plants can get nutrients from the soil instead of fertilizer.”

While gardeners have differing opinions on how “native” a plant should be, whether a garden should contain only native species, and whether those species should be native to Rhode Island, New England or beyond, more people are choosing to plant natives, even if it’s just a few to start. This higher level of awareness is evident in the recent growth of the membership of the nonprofit Rhode Island Wild Plant Society, which, in the past two years, has gone from about 400 members to more than 600.

Society vice president Sally Johnson said she is not sure why the organization has so many new members, but she said it is probably due to people spending more time at home as well as growing concerns about the climate crisis.

“A lot of us are out in our yards, outside more, and a lot of us are going for more walks because it’s COVID-safe, so we’re appreciating nature more, and that’s got to contribute to it,” she said. “The other factor, and this is my gut feeling on it, it’s got to be global warming. We see so much environmental destruction. There’s so much talk of resiliency. That contributes.”

Johnson also noted people were becoming more aware of the need to support pollinating insects and birds.

“People are going from the purely ornamental, showy plants, and understanding more the role of supporting pollinators and host plants,” she said. “The understanding of, it’s not just the pretty bees and butterflies, but it’s also the wasps and who’s going to live there over the winter and leaving your perennials up over the winter so that insects can overwinter in them.”

Michael Adamovic, author, photographer and and a botanist at Catskill Native Nursery, attributes the greater interest in native plants to the noticeable decline in insect populations.

“Natives are definitely increasing in popularity,” he said. “Probably one of the main reasons is that because in the last 20, 30 years, there’s been a large decline in insect populations. You would take a road trip, 20 or 30 years ago, and your car would be completely covered with insects. These days, you’re lucky if you get one or two splattered on it. The same thing goes for songbirds. The songbird population is really starting to decline, and people are finally starting to realize there’s something wrong with the environment.”

Adamovic said sales at the nursery took off during the pandemic and continue to be strong.

“Our sales probably at least doubled from the previous year,” he said. “We couldn’t keep up with the demand. And even last year, 2021, it was still going in the same direction and there’s no indication of it slowing down.”

Johnson, who owns a garden design business that uses native plants, said they can still be hard to source in Rhode Island, and she often has difficulty finding them for her clients.

“You can’t find native species,” she said. “… I had a client who had to put in native plants for a CRMC [Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council] permit by the end of October and she could only put in three species.”

The Rhody Native program, a federally funded initiative of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, began in 2010, but ended in 2018. The initial objectives were to provide enhanced job training for unemployed nursery workers following the recession, and plant native species to fill the spaces where invasive plants had been removed.

“The idea was, all right, here’s another economic opportunity,” Gregg said. “Let’s gather seed and cut clippings from local sources and we’ll pay out-of-work nurserymen to grow them up for us. And then, we will use them in restoration projects and we’ll let nurseries and garden centers sell them to try to change people’s minds about natives.”

But when the federal funding ended, the idea of building a local native plant supply chain ran up against the realities of the nursery business.

“You can’t pay a professional staff on the kind of volume we were doing in Rhody Native plants, and there’s a couple of reasons,” Gregg said. “One is, the margins on propagating nursery stock are so thin, you have to do zillions of plants in order to make a business out of it. For native plants, you still have to order from far away because it won’t pay. We didn’t have the right model for making local plants pay.”

There was also an issue, Gregg added, with a tax-exempt nonprofit operating on tax-exempt land competing with commercial growers in Rhode Island.

Current garden trends favor native plants, a change Adamovic has also observed.

“They are going more toward native plants than they are non-native,” he said. “We still get a few people who don’t get it at all. They’ll come in and have this huge list of non-natives. They don’t really understand what the whole native thing is about, but every year that goes by, that’s decreasing.”

Johnson believes gardeners evolve at their own pace, and some people will adopt native plans more readily than others.

“I think you have to accept people for where they are and try to just gently move them,” she said. “We as a wild plant society are trying to move towards being purists, of only selling plants from Rhode Island and trying to get out seeds from Rhode Island, and I totally support that effort. … It’s important to realize that hey, if you don’t want to do your entire garden as native plants, at least start putting some in and start looking at them and thinking about them, and then you realize ‘Hey, the native goldenrod is kind of nice.’”

It is becoming increasingly important, Adamovic said, that people include native plants in their gardens.

“It’s really rewarding, too,” he said. “You put a native plant in your garden and you’re able to see that the caterpillar that ate it turned into a butterfly. You’re also providing a bunch of food for wildlife in general, and you’re really helping to save the environment by switching over to using natives.”

For Gregg, native plants are the foundation of Rhode Islanders’ sense of place.

“Rhode Islanders live in a place that has oak trees that drop their leaves in the winter and it’s got stone walls with moss and asters growing along them and it’s got native beach grasses,” he said. “You go to the beach, you see the little waving grasses. … If you want a place with palm trees and eight foot-high elephant grass, go somewhere else. Rhode Island is about a sense of place. It’s about our native plants.”

Native plant resources

Rhode Island Wild Plant Society native plant sales.

Xerces Society pollinator-friendly native plant lists.

Cynthia Drummond is an ecoRI News contributor.

Tim Faulkner: Localities stepping in to address ocean plastic crisis

Plastic pollution, especially in the ocean and along the coast, such as these plastic jugs found on the Portsmouth, R.I., shoreline, is a significant global problem.

Photo by Frank Carini of ecoRI News.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s Save Our Seas Act has big goals for addressing plastic in the oceans. The bipartisan bill that passed out of the Senate last year seeks to tackle marine debris and the ballooning problem of plastic waste by authorizing $10 million annually for cleanups of severe debris events in waters across the country. It also restarts federal research to determine the source of marine trash and the steps needed to prevent it.

What is already known is that much of the 8 million tons of plastic waste dumped in the world’s oceans each year happens outside the United States. In fact, five countries — China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam — are responsible for 60 percent of the plastic garbage that makes it into our waters every year, according to the Ocean Conservancy.

That’s a problem, because most of those five countries receive plastic from U.S. recycling centers. The recycling industry, however, is lightly regulated, so it's hard to know the fate of the millions of bales of plastic recyclables shipped overseas annually.

The Save Our Seas Act addresses this problem by encouraging the president and the State Department to address the marine debris problem with these high-polluting nations. It also encourages international research into biodegradable plastics and establishes prevention strategies.

However, the likelihood of an environmental bill passing in the current Congress, much less President Trump endorsing it, is low. Trump wants to cut $1 billion from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which overseas the marine-debris program.

For now, much of the action on marine garbage is happening at state and local levels. Those steps include greater enforcement of recycling rules, bans on certain plastics, and improvement by product manufactures to make their packaging more environmentally friendly, reusable and include take-back programs for hard-to-recycle and bulky items.

At a recent Earth Day event in Middletown, R.I., aimed at drawing attention to the Save Our Seas Act, Johnathan Berard of the Rhode Island chapter of Clean Water Action said, “We cannot recycle our way out of this problem. We will only be able to solve it through policies that stop plastic pollution at its source.”

Recycling is necessary but is vulnerable to economic and market pressures, which cause revenues for waste prevention and education to fluctuate. There is little enforcement of rules, such as requirements in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut that all business collect recyclables and offer collection for their customers. There is even less oversight of what happens to recyclables once they leave sorting centers and are shipped around the world. And with the exception of metals and glass, plastics eventually lose their durability and are down-cycled to trash.

Depending on the item, recycling rates hover between 20 percent and 30 percent nationally. Requiring a deposit on glass and plastic bottles, so-called “bottle bills,” boost the recycling rate to nearly 90 percent. But the political will for bottle bills is poor. For example, legislation is introduced in the Rhode Island General Assembly each year but rarely makes it out of committee.

The 2018 bill has yet to be scheduled a hearing. Massachusetts has had a successful 5-cent bottle-deposit program since 1983, but voters defeated a referendum in 2014 to expand the collection to include non-carbonate beverage bottles.

Take-back programs for bulky and hard-to-recycle items such as mattresses, paint cans and electronic waste have also made a difference, but expanding programs to other items like light bulbs, syringes and medications have stalled, as manufactures and retailers resist raising prices to fund collection or improvement of packaging.

This resistance puts the cost of waste management and recycling on consumers and local governments who pay for clean up and transportation. Budget limitations have led to the most cost-effective solution: bans. Prohibitions and fees on plastic bags, in particular, have proven effective at reducing land and marine debris. Dozens of communities in Massachusetts have banned plastic bags and a handful have enacted bans on polystyrene cups and to-go containers.

Seven Rhode Island communities have passed bag bans and more are considering them. Block Island even added a ban on balloons, and the “skip the straw” movement is growing among consumers and restaurants.

While bag bans and beach cleanups are helping clean southern New England, there is still the problem of global waste. Global plastic production is expected to double within 10 years and by 2050 there will be more plastic waste by weight in ocean waters than fish.

The Ocean Conservancy says a combination of education, waste collection and recycling infrastructure, and better managed and properly cited landfills are needed to tackle the plastic ocean debris epidemic.

“While we have made enormous progress cleaning up Narragansett Bay, the millions of tons of trash that are dumped into the oceans around the world can wind up on American shores and in the nets of Rhode Island fishermen,” Whitehouse said.

Tim Faulkner reports and writes for ecoRI News.

Wood is actually a bad source of energy for New England

Firewood.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

'New England has lots of woodland and so we’re tempted to see biomass as a good source of “renewable energy.’’ The theory goes that, yes, burning wood, notably in the form of wood pellets, releases carbon dioxide but growing trees absorbs it and so the whole process can be seen as “carbon neutral’’.

But a report from an outfit called Not Carbon Neutral says that CO2 emissions far exceed the absorbing capacity of the living trees planted or maintained as future fuel sources. The report’s author, Mary Booth, told ecoRI News journalist Tim Faulkner:

“This analysis shows that power plants burning residues-derived chips and wood pellets are a net source of carbon pollution in the coming decades just when it is most urgent to reduce emissions.’’ She included in her calculations the fossil-fuel emissions from the shipping and manufacturing of wood fuels.

Southern New England gets some electricity from burning wood in northern New England.

The report reminds me of the wood-burning mania in New England during the energy crises of the ‘70s. It was handy to have all that wood available for heating in New England to offset a little the swelling price of heating oil, but the wood stoves caused serious air pollution in many parts of our region, including in rural areas once noted for their clean air.

So wind, solar and hydro are the way to go in New England’s energy future.

To read Mr. Faulkner’s article, please hit this link:

https://www.ecori.org/renewable-energy/2018/2/26/report-says-wood-based-energy-doesnt-add-up

Stop the theft from stone walls

By TIM FAULKNER for ecoRI News

Via ecori.org

PROVIDENCE

Preserved open space in Rhode Island needs additional protections, because poachers steal rocks from stone walls and nearby residents cut down trees to improve their views.

Currently, there is no deterrent or penalty for intentionally damaging or building on land protected from development. If caught, the thief or vandal simply has to pay a portion of the value of the damaged or stolen items, such as the timber value of a cut tree.

Rupert Friday, director of the Rhode Island Land Trust Council, testified at the Rhode Island General Assembly on Jan. 18 in favor of a bill that would make such offenses a civil violation.

“The current penalties are little more than a hand slap,” Friday said. “The current penalty if you steal a stone wall and you get caught and convicted is you have to put the stone wall back. It’s pretty lucrative if you don’t get caught.”

Meg Kerr, senior director of policy for the Audubon Society of Rhode Island, said such legislation would help protect 9,500 acres of open space and wildlife habitat that Audubon owns and manages. Kerr said it’s common for landowners living near protected coastal areas to cut down trees on protected land to improve their views of the water.

“This legislation will provide a greater deterrence and keep people from blatantly damaging our communities’ open space and our significant investment to protect these special place,” Kerr said in testimony before the House Judiciary Committee.

The bill was held for further study and will likely have another hearing on Jan. 24. It's the third year in a row that the bill has been introduced. Last year, the bill passed in the House but stalled in the Senate.

The bill is modeled after a bill passed in Connecticut in 2006 that was intended to address the same problems faced by land trusts, municipalities, the state, environmental groups, and other owners and managers of open space.

In the legislation, open space is defined as any park, forest, wildlife management area, refuge, preserve, sanctuary or green area owned by one of those entities. Damage, called encroachment, is defined as intentionally erecting structures, roads, driveways or trails. It includes destroying or moving walls, cutting trees and vegetation, removing boundary markers, installing lawns or utilities, and storing vehicles, materials and debris.

The civil fine for a violation could amount to five times the cost of the damage up to $5,000.

The bill is sponsored by Rep. Cale Keable (D.-Burrillville).

Todd McLeish: Feral cats are ravaging the wildlife around us

A feral cat with prey.

A new book examining the complicated issue of cats and wildlife has re-opened a difficult discussion that has long pitted animal welfare organizations against biologists, birdwatchers and the environmental community. And the position taken by authors Peter Marra and Chris Santella is doing little to make that discussion any easier.

You can tell by its title, Cat Wars: The Devastating Consequences of a Cuddly Killer, that the authors don’t pull any punches. Marra, who directs the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, and Santella, a journalist, argue that drastic action is necessary to curb the massacre of birds and small mammals caused by feral cats and house cats that are allowed to go outside.

After reviewing thousands of reports, pet-owner surveys, cat regurgitation studies, academic research and other data, they calculated what they say is a conservative estimate: Cats kill up to 22 billion small mammals, 4 billion birds, 822 million reptiles and 299 million amphibians in the United States annually.

“More birds and mammals die at the mouths of cats than from wind turbines, automobile strikes, pesticides and poisons, collisions with skyscrapers and windows, and other so-called direct anthropogenic causes combined,” they write.

What’s more, the authors say that feral cats are also a hazard to human health. Feral cat colonies where humans provide food to the felines attract raccoons, skunks, foxes and coyotes, easing the spread of rabies. Cats also carry a variety of diseases that can be transmitted to humans, from a bacterium that causes a life-threatening infection in cat scratches and bites to a parasite that can cause birth defects when pregnant women are exposed to cat feces.

The authors call feral cats an invasive species and say the only answer to solving the problem is what is euphemistically called “trap and remove,” which means capturing the animals and euthanizing them.

“No one likes the idea of killing cats,” they write. “But sometimes, it is necessary.”

It’s unclear how many feral cats live in little Rhode Island, but all the interested parties agree it’s too many. Estimates range as high as 250,000, though state veterinarian Scott Marshall said it’s probably closer to “tens of thousands.”

He established a Feral Cat Working Group in 2010 after receiving innumerable complaints about the animals. The group, which includes members from animal welfare groups, academia, environmental organizations and public-health agencies, hired a student from the Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine to census known feral cat colonies in the state. She found 302 colonies, mostly in urban areas, with a total of about 4,000 cats.

It’s believed there are many more colonies than those she surveyed, plus thousands of uncounted cats that aren’t part of established colonies and an estimated 60,000 house cats whose owners let them go outside.

“Cats are a serious problem for wildlife,” Marshall said. “Their hunting instinct isn’t diminished by feeding them. A pet cat that is fed at home still brings birds and rodents home. We can’t deny that they’re having an impact on wild birds, rodents and to a lesser extent reptiles. They kill whatever they can get.”

According to Marshall, feral cats live very short lives. Their life expectancy is less than two years. Half don’t make it out of kittenhood; 75 percent don’t survive one year, and 85 percent die before their second birthday.

“People don’t realize that when animals are dying young in large numbers, they have a miserable life and a miserable death,” he said. “They’re struck by cars, exposed to parasitism, die of exposure, get ripped to shreds by predators. They don’t live good lives.”

He agrees with the authors of Cat Wars that, unfortunately, the best solution is euthanasia.

“Given the tools we have, that’s the only way to solve it,” Marshall said. “If a male contraceptive were available, that could be effective, but right now nothing else works.”

Most of the animal-welfare groups in Rhode Island disagree. Vehemently. They argue instead for a method called “trap, neuter and return,” or TNR, in which feral cats are captured at colonies, brought to clinics to be spayed or neutered, and returned to their colony. Advocates say it’s the most humane alternative to euthanizing the animals, and because the cats can no longer reproduce, the colonies will eventually disappear.

Gil Fletcher, a member of the Feral Cat Working Group who runs a cat-rescue organization called PawsWatch, acknowledges that not all of the animal-welfare groups agree with the “return” component of TNR, and because there are numerous small grassroots groups advocating for feral cats, there is considerable tension among them. But, he wrote in a recent e-mail, “it goes without saying that any form of large-scale lethal approach to reducing the free-roaming cat population (trap and euthanize, hunting, targeted poisoning, etc.) is an anathema to this group.”

Fletcher is pushing for municipal governments to adopt the TNR approach, because the feral-cat problem is one he equates with other community concerns addressed with taxpayer funds, like anti-littering campaigns and roadside beautification efforts.

While he barely mentions the impact of cats on wildlife — other than to disagree with the cat predation numbers Marra and Santella claim — he said “the cat people” and “the wildlife people,” as he calls them, all seek to remove free-roaming cats from the outdoor environment. Their “interest, motivation and their presently favored means are poles apart, but the end goal is the same,” he said. “By all logic, they should be natural allies.”

Part of the reason they aren’t, according to Marshall and the scientific community, is that there is no evidence that TNR works. In practice, feral cat colonies managed with TNR don’t get smaller and disappear. Instead, the populations remain mostly the same and the animals continue to kill wildlife. To be successful, at least 80 percent of the cats in a colony must be spayed or neutered, and the colonies must be constantly monitored as new animals arrive.

“TNR seems to be the panacea that animal-welfare groups endorse, but there’s virtually no evidence that it’s effective,” Marshall said. “Everybody wants it to be effective, but it’s very labor intensive, expensive, and ultimately it’s ineffective. Unless people can shut down new inputs into the colonies, it’s doomed to fail.”

The one thing that Marshall and Fletcher agree on is that it will be nearly impossible to address the issue of feral cats in Rhode Island without public support for whatever strategy is chosen. And they both say the public won’t support a widespread euthanasia effort.

“The science would say that cats should be removed from the environment, but emotions run very high and there is no public support for removal,” Marshall said. “I personally don’t like the idea of tolerating their existence, because in my opinion the lives and deaths they experience are far less humane than trapping and removing them.”

The authors of Cat Wars, however, are less concerned with the sad lives of feral cats and more concerned for the welfare of wildlife and the environment. They say that of all the threats to birds that are directly or indirectly caused by humans, cats are the easiest problem to fix, especially when compared to complex issues such as climate change.

“To me, this should be the low-hanging fruit,” Marra is quoted in Smithsonian Magazine. “But as it turns out, it might be easier stopping climate change than stopping cats.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Cape Cod fishermen are challenged by huge mid-water herring trawlers

By Nicole St. Clair Knobloch

for ecoRI News (ecori.org)

CHATHAM, Mass.

Cape Cod fishermen may be on their way to some relief from sharing inshore fishing grounds with mid-water herring trawling, a practice they say is threatening their livelihoods. But a persistent lack of data on the impact of the trawls may hamper efforts to regulate them.

On Aug. 17, the Herring Oversight Committee of the New England Fisheries Management Council voted to send the council two options for establishing a buffer zone prohibiting mid-water trawling off Cape Cod. The zone would extend either 12 miles or 35 miles from shore — significantly farther than the 6-mile zone proposed by the herring industry and closer than the 50-mile mark sought by environmental groups. The council will consider the options when it meets in September.

Fishermen have been complaining for years about the industrial-sized ships landing on the back side of Cape Cod, scooping up millions of pounds of herring and leaving, they say, a temporary ocean “bio-desert” in their wake.

In 2015, the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance collected hundreds of comments and individual letters from fisherman about the phenomenon called “localized depletion” — defined as “when harvesting takes more fish than can be replaced locally or through fish migrating into the catch area within a given time period.”

For those who fish bluefin tuna, striped bass, dogfish and are still recovering from drastic cuts to allowable catches of groundfish such as cod, competing with the large ships doesn’t feel like a fair fight.

“We have a problem on the back side of the Cape,” said striped bass fisherman Patrick Paquette at the recent committee hearing. “We have big industrial boats fishing in shallow water.”

The comments were part of a new look at how herring fishing should be managed. The New England Fisheries Management Council (NEFMC) was tasked in 2007 with establishing a control rule for herring stocks. But in 2014, a lawsuit from environmental groups prompted an examination of the biological and ecological role of herring in the western Atlantic Ocean ecosystem, with the aim of establishing a stronger control rule reflecting the herring’s status as a forage species.

Even if the NEFMC is able to determine that role, and assign a new acceptable biological catch limit for herring, its science committee asserts that stronger stock-wide limits wouldn’t necessarily avoid local effects on the food web when trawlers come through.

A local dogfish fisherman, who didn’t want to use his name for fear of “retribution” from the herring companies, described the experience of encountering a mid-water trawler inshore.

“We go out and they’re out there with their lights off, inside of three miles (from shore),” he said at the Chatham dock two days before the Aug. 17 meeting. “They see us and turn their lights on, and plow right through our lines, leaving no groundfish. We might as well just go home and call it a season.”

The herring industry disputes such claims, as proving them has been problematic. At the August meeting, the task force charged with analyzing the impacts of midwater trawling on other species presented few results. Though it confirmed significant numbers of trawler landings in Area 114, a section of ocean on the “back” of Cape Cod, it didn’t show the effect of that activity on other species. NEFMC staff cited lack of reported data and noted the lack of an adequate computer model and the time to develop one.

The staff did find that both large and small schools of tuna, which prey on herring, are lower in New England now than in the 1980s, but suggested lack of prey as only one of several possible explanations for the decline.

“Year after year, we have no scientific basis for taking any action on herring. We have no evidence localized depletion exists,” said Herring Oversight Committee member Mary Beth Tooley, who is on the board of O’Hara Industries, a herring company operating two mid-water trawlers out of Rockport, Maine.

Herring fisherman Gerry O’Neill got up from the audience to agree with Tooley.

“I feel this whole thing is going forward based on perception, not based on facts,” he said. “The research — there are ways to do it. We’d like to see it done. If we are going to lose access to fish we would like some biological, scientific basis for it.”

Getting that level of proof in New England is difficult, according to John Pappalardo, CEO of the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance.

“We don’t have synced or simple data collection systems on each fishery,” he said. He pointed to Alaska, where herring fishing is intensely monitored and pair trawling is limited to a few areas. There, he said, “Industry is more involved in the collection of that data. It’s partly the (New England) culture, which is a resistance to being observed or monitored.”

Making that happen here, Pappalardo said, is up to Congress and the National Marine Fisheries Service. “Where is the political will?” he asked.

He expressed exasperation with the idea that a connection between herring trawls and other species had to be proved absolutely.

“These people will not draw a correlation,” he said. “(For them) there is always something else to eat in the ocean.”

Even without more data, NEFMC’s Atlantic herring management plan was amended in 2006 to ban midwater trawling in the summer in the inshore area for the entire Gulf of Maine. The ban ends just above the fishing area of Cape Cod. It came after thousands of comments from Gulf of Maine fishermen with similar complaints as their Cape Cod counterparts.

At the September meeting, the council is expected to hear the science committee’s findings on how much herring is needed to support the area’s ecosystem.

To some, herring’s role is obvious, even if acceptable catch levels are not.

“The ecosystem starts with herring,” said the Chatham dogfish fisherman. “Am I the only one that remembers that part in elementary school? When they drew a circle around a herring and said the food chain starts here.”

Tropical fish are arriving earlier in the summer in Narragansett Bay

A crevalle jack.

By TODD McLEISH, for ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When a tropical fish called a crevalle jack turned up this summer in the Narragansett Bay trawl survey, which the University of Rhode Island conducts weekly, it was the first time the species was detected in the more than 50 years that the survey has taken place.

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s (DEM) seine survey of fish in Rhode Island waters also captured a crevalle jack this year for the first time.

While it’s unusual that both institutions would capture a fish they had never recorded in the bay before, it’s not unusual that fish from the tropics are finding their way to the Ocean State. In fact, fish from Florida, the Bahamas and the Caribbean have been known to turn up in local waters in late summer every year for decades. But lately they’ve been showing up earlier in the season and in larger numbers, which is raising questions among those who pay attention to such things.

“There’s been a lot of speculation about how they get here,” said Jeremy Collie, the URI oceanography professor who manages the weekly trawl survey. “Most of them aren’t particularly good swimmers, so they probably didn’t swim here. They don’t say, ‘It’s August, so let’s go on vacation to New England.’ They’re not capable of long migrations.”

Instead, fish eggs and larvae and occasionally adult fish are believed to arrive in late summer on eddies of warm water that break from the Gulf Stream. Collie said they “probably hitch a ride” on sargassum weed or other bits of seaweed that the currents carry toward Narragansett Bay.

Most of these tropical species, including spotfin butterflyfish, damselfish, short bigeye, burrfish and several varieties of grouper, don’t survive long in the region. When the water begins to get cold in November, almost all perish.

“There’s no transport system to carry them back south, which is the reason they can’t get back where they came from,” Collie said.

While climate change and the warming of the oceans has been responsible for many unusual marine observations in recent years, that doesn’t appear to be the case with the annual arrival of tropical fish in local waters.

“Warming doesn’t really have an effect on it,” said Mark Hall, owner of Biomes Marine Biology Center in North Kingstown, which has been exhibiting locally caught tropical fish since it opened in 1989. “It’s just the way the Gulf Stream meanders and carries these fish our way.”

Ocean warming does appear to be affecting the timing of the arrival of the fish, however.

“Twenty years ago I wouldn’t bother trying to find tropicals until mid-August, but now we’re seeing them in July,” Hall said.

The good news is that none of these tropical species appear to be harming or out-competing the native marine life in Narragansett Bay.

“They arrive in July or August and are dead by November, so they’re just not here long enough to have an impact,” Hall said. “I can’t think of a single animal that’s having a negative effect.”

Collie agrees. “These strays are small and appear here in small numbers. The threat would come from wholesale movements of new species that can stay here for long periods. Tropicals aren’t a threat.”

For those interested in seeing some of the tropical species that are making their way to Rhode Island, visit Biomes in North Kingstown or Save The Bay’s Exploration Center and Aquarium at Easton’s Beach in Newport. Save The Bay just opened a new exhibit this month featuring tropical fish species collected locally by its staff, volunteers and partner organizations, including the Norman Bird Sanctuary and DEM. The exhibit, called The Bay of the Future, features a variety of what manager Adam Kovarsky calls Gulf Stream orphans.

“We want to spark people’s thought processes about the things that can happen from climate change,” he said. “While tropical strays have been showing up here forever and ever, there’s evidence that now they’re showing up in larger numbers and arriving earlier and surviving later. It’s not a problem now, but eventually they may stay year-round, and that could stress our local species.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

New England's risky bet on a population explosion of casinos

By PEARL MACEK for ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NEWPORT, R.I.

Walk through the automated doors at the Newport Grand Casino and the cacophonic sound of more than 1,000 slot machines greets you. As your ears become accustomed to the multiple layers of sounds, an inundation of vivid purples, blues, reds and yellows flash before you as each machine tries to entice potential players.

Slot machines called “Lucky Larry’s Lobstermania,” “Sex and the City” and “Cleopatra” seem innocent enough, but after you insert your money, a digital message gives you a hotline number to call if your gambling has become problem. Nearby, virtual blackjack dealers, big-breasted women with smiling faces, wait patiently inside their respective screens for real players.

It’s a Thursday evening and the crowd, mostly an elderly one, sits before colorful screens waiting to hit the jackpot. On this particular night, however, the casino isn’t anywhere near capacity, which is probably one of the reasons that the Twin River Management Group (TRMG) wants to close it.

TRMG operates Twin River Casino in Lincoln, a Hard Rock Hotel in Biloxi, Miss., and Arapahoe Park, a horse-racing track in Colorado. The management group officially announced that it had acquired Newport Grand last July, but it was already public knowledge that the company would seek to move Newport Grand’s gaming license to a new site, possibly in Tiverton, which seemed more open to hosting a destination casino.

“When we acquired Newport Grand we acquired it not thinking we would be able to do many things with it other than operate it as it was,” said John E. Taylor Jr., chairman of the board of directors of Twin River Worldwide Holdings, the parent company of TRMG, during a recent phone interview with ecoRI News. “But we wanted to see if there was a possibility that there was another community in a more advantageous location that might consider hosting a facility like this.”

Table games are considered by the gaming world as a vital way of attracting a larger, younger demographic, but twice Rhode Island voters, particularly Newport voters, said “no” to table games at Newport Grand. It seems the last majority “no” vote, in 2014, sealed Newport Grand’s fate.

Gambling with economy

The fiscal 2015 financial report of the Lottery Division of Rhode Island’s Department of Revenue states that $516,262,400 in revenue was generated by video lottery (slot) machines and $106,640,942 was generated by table games. Together, they make up 71.9 percent of the gaming industry in Rhode Island, which brought in a total of $867,054,081 during the last fiscal year.

Rhode Island’s gaming industry is the state’s third-largest revenue source.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2015, TRMG held a series of talks and charrettes in Tiverton to explain to residents the company’s design plans for the proposed casino. According to Taylor, residents seemed receptive to the idea.

“We thought that the market could support 1,000 machines, comparable to the number that they have at Newport Grand, and we thought about 30 table games could be supported,” he said. “But what we told the residents is that we’re having this conversation to see what else you would feel comfortable with.”

In early November of last year, TRMG presented its plan to the Tiverton Town Council: a two-story, 85,000-square-foot facility with an attached 84-room hotel and 1,100 surface parking spaces. The proposed casino would be set on 23 acres on a 45-acre parcel just off Stafford Road and 400 feet from the Massachusetts border.

From this location, it’s a 50-minute drive to Plainridge Park Casino, in Plainville, Mass., and 30 and 43 minutes from Taunton and Brockton, respectively, where two casinos are slated to be built. A $1.7 billion Wynn Boston Harbor casino in Everett also has been proposed.

Taylor said TRMG isn’t too worried about the possibility of three more casinos opening in the area. “Convenience is critical,” he said. “The more convenient that we can make it for people to get to, the better.”

The proposed Tiverton casino would employ between 525 and 600 employees, according to Taylor, and all of Newport Grand’s 175 employees would have the opportunity to work at the casino in Tiverton.

Voters to decide

Earlier this year, both chambers of the General Assembly overwhelmingly approved legislation to give Rhode Island residents the opportunity to vote for or against a Tiverton casino. The legislation was signed by Gov. Gina Raimondo the next day. Questions regarding the casino will be put on the November ballot. The proposal will have to receive a majority “yes” vote from both state voters and Tiverton residents.

Should the ballot questions win approval, the state would receive 15.5 percent of table revenues and 61 percent of video-lottery terminals (VLTs), from both from the new Tiverton casino and Twin River. The legislation would also guarantee each host community $3 million annually from the casinos.

“They (casinos) have been, up to this point, considered to be a real success story, but I do consider the fact that they are such a large part of our state’s revenue to be a real issue for worry and to some extent, a failure of Rhode Island to really get its growth-oriented sectors going,” said Leonard Lardaro, an economics professor at the University of Rhode Island. “What we’re looking at, and I think it is important to put it in this context, is that the gambling industry is very over supplied, very, very oversupplied.”

Patrick Kelly is the chair of the department of accountancy at Providence College. He has studied casinos and their social and economic effects, specifically in the southeastern Connecticut region. Kelly said that in the coming years “there is going to be a lot more commitment to casinos for revenue and jobs,” not just in the Northeast but throughout the United States. He said that is a concern.

By 2018 he expects to see some 60 casinos along the Route 95 corridor between Maine and Maryland, including three or four in Massachusetts, two in Rhode Island and two or three in Connecticut. Kelly said this will ultimately lead to market saturation, but a greater concern of his are the social costs related to having so many casinos, such as problem gambling and an increase in criminal behavior to support gambling addiction.

About 3 percent of the U.S. population is addicted to gambling, while others are hooked by the lure of tax revenue and an economic rescue. (istock)

Addicted to gambling

Tawny Solmere is the director of Problem Gambling Services of Rhode Island (PGSRI). She said that between 1 percent and 3 percent of the U.S. population has a gambling problem, “so that means, with the census of Rhode Island, that we are looking at between 10,000 and 30,00 people” who have problems with gambling.

PGSRI is a hotline service. When people call, they are referred to a counselor at one of the six behavioral health-care clinics run by the nonprofit CODAC Behavioral Healthcare. The lottery subsidizes PGSRI, but Solmere said more help from the state would be welcomed, especially if the casino industry continues to expand.

She noted that co-dependencies, such as drug and alcohol abuse, tend to accompany gambling addiction. But there is an aspect to problem gambling that is particularly egregious. “This disorder, problem gambling, has the highest rate of suicide than any other addiction,” Solmere said.

Solmere said PGSRI and CODAC are neither for nor against casinos, but she is worried that unless more is done to help those with gambling addiction, the situation could easily spiral out of control.

“If we don’t get the resources to meet that need, Rhode Island is going to have an epidemic equal to the heroin epidemic we are looking at now,” she said. “It’s a scary prospect.”

Rep. John Edwards, D-Tiverton, said building the casino in Tiverton “just makes sense” and will offer local residents a large number of employment opportunities. As far as gambling addiction, he said, “You worry a little bit about that,” but, “if they are going to gamble, they are going to gamble somewhere.

“I think that it will be an asset for the Tiverton and the whole East Bay area.”

George Medeiros, a longtime Tiverton resident and owner of Tiverton Sign Shop, agreed. “It’s just something for this area,” he said during a recent phone interview. He noted that there is little to attract people to Tiverton, and for it’s residents, there are few dining and entertainment options.

“For me to get a pizza right now, I would have to go to Fall River or the other side of Tiverton,” Medeiros said.

He said he isn’t worried about traffic congestion, as the casino will be located just off the Route 24 ramp, and according to a TRMG press release from November 2015, the Rhode Island Department of Transportation is planning to build a roundabout on Canning Boulevard with a dedicated turn lane into the proposed casino.

The only thing that worries Medeiros is if the proposed casino in Taunton opens before the Tiverton casino. “They might not be fast enough,” he said.

Brett Pelletier is a member of the Tiverton Town Council and the only one to oppose putting questions about the casino on the November ballot. He also was the only council member to respond to an ecoRI News request for comment.

Pelletier, who is a real-estate analyst with a consulting firm in Boston, was appointed to a Town Council subcommittee to vet the casino legislation and provide feedback before it went to the General Assembly.

“Every time that the meeting was meant to take place, it was canceled for one reason or another,” he said. “We never actually met.”

In regards to Rhode Island’s dependency on the gaming industry, Pelletier said, “I think that it’s an atrocious way to run a government, preying on people who have an unjustified hope that they will strike it rich at a casino.”

Economic impact

The Brockton and Taunton casinos are scheduled to be built by the end of 2018. TRMG has taken the possibility of those facilities opening by then into consideration in its gaming market study.

The company has included four different scenarios, including the Brockton casino entering the market but Taunton doesn’t. The report estimates $127.6 million in revenue if that were to happen. If neither of those casinos opened, the report estimates $147.9 million in revenue for the Tiverton facility.

TRMG has worked closely with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management to identify developable land, according to the company, and it hired the firm Natural Resources Services Inc. to suggest mitigation plans for any adverse impact on local wildlife.

Rachel Calabro, a community organizer at Save The Bay, said the Providence-based nonprofit has yet to look deeply into the possible environmental effects of a Tiverton casino. She has seen the plans for the site and suggested that they reduce the amount of parking surface area by building a garage instead. The amount of concrete surface space initially suggested for the casino could lead to serious flooding issues, Calabro said.

She also suggested the installation of solar panels.

Casinos in Tiverton, Taunton and Brockton could certainly become go-to destinations, but the continued reliance on this revenue raises legitimate questions: Can the Rhode Island gaming industry continue to be a leading revenue source given the inevitable construction of more casinos in Connecticut and Massachusetts? Will the gaming industry last and will it be worth the social costs?