William Morgan: Raymond Hood and the drama of the American skyscraper

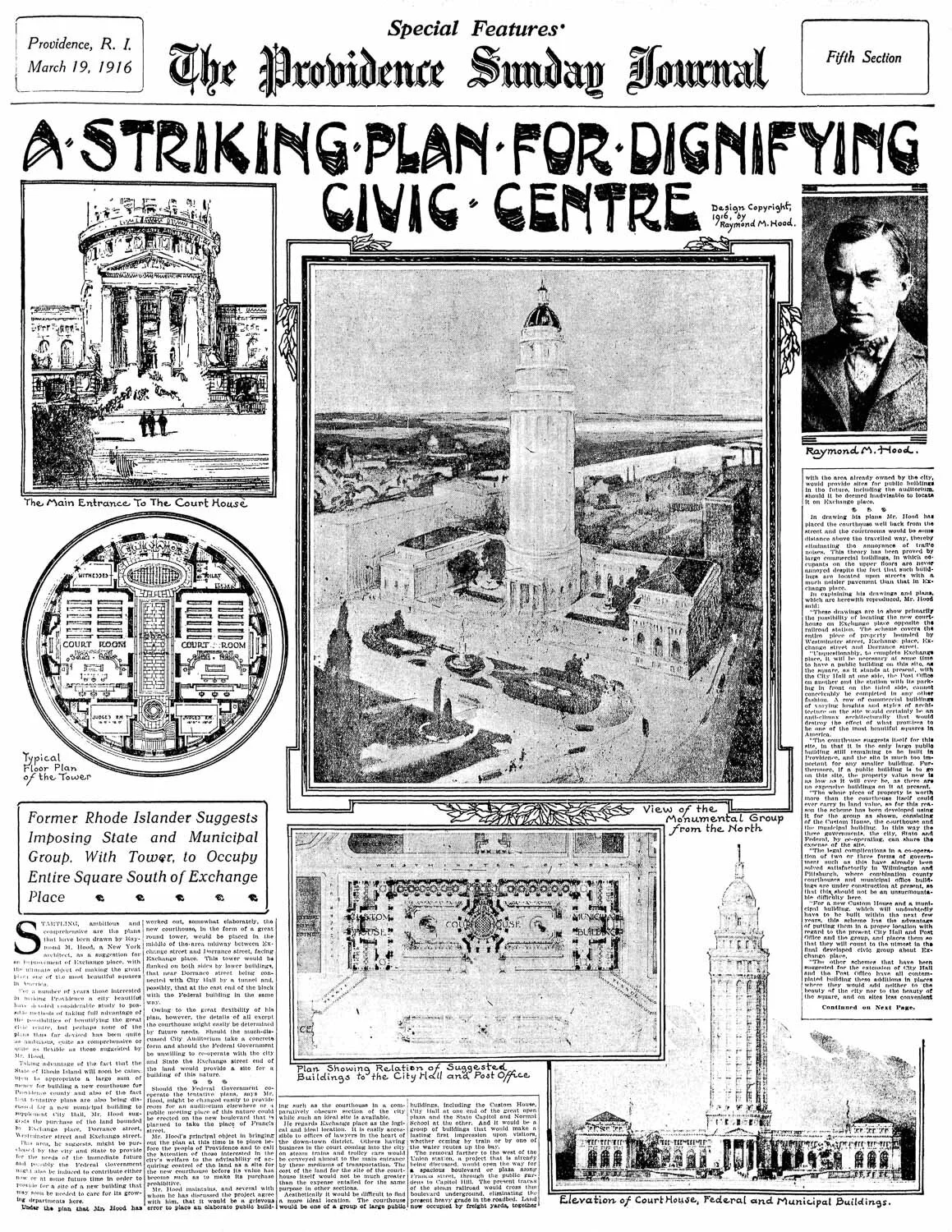

In 1916, a little known, 35-year-old architect and Rhode Island native proposed a monumental civic structure for downtown Providence. Raymond Hood's Civic Centre would have been sited where the Industrial Trust Building was later built; it was to be 600 feet tall and would serve as courthouse, library and prison. Its tower would symbolize progress and prosperity at the head of Narragansett Bay.

A few years earlier, Hood had done his thesis at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts, in Paris, on a design for a city hall for his hometown of Pawtucket. While neither of these fanciful schemes was built, they demonstrate the early vision of a man destined to become of one of the 20th Century's most significant skyscraper architects.

Raymond Hood, Proposed City Hall for Pawtucket. Year-Book of the Rhode Island Chapter, American Institute of American Institute of Architects, 1911

“Raymond Hood and the American Skyscraper,’’ an exhibition initially organized for showing to the public at the David Winton Bell Gallery, at Brown University, opened online only on Sept. 11. The show, underwritten by the Brown Arts Initiative and Shawmut Design & Construction, features loans of drawings and photographs from RISD, MIT, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania and the Smithsonian Institution. Hit this link to see the show.

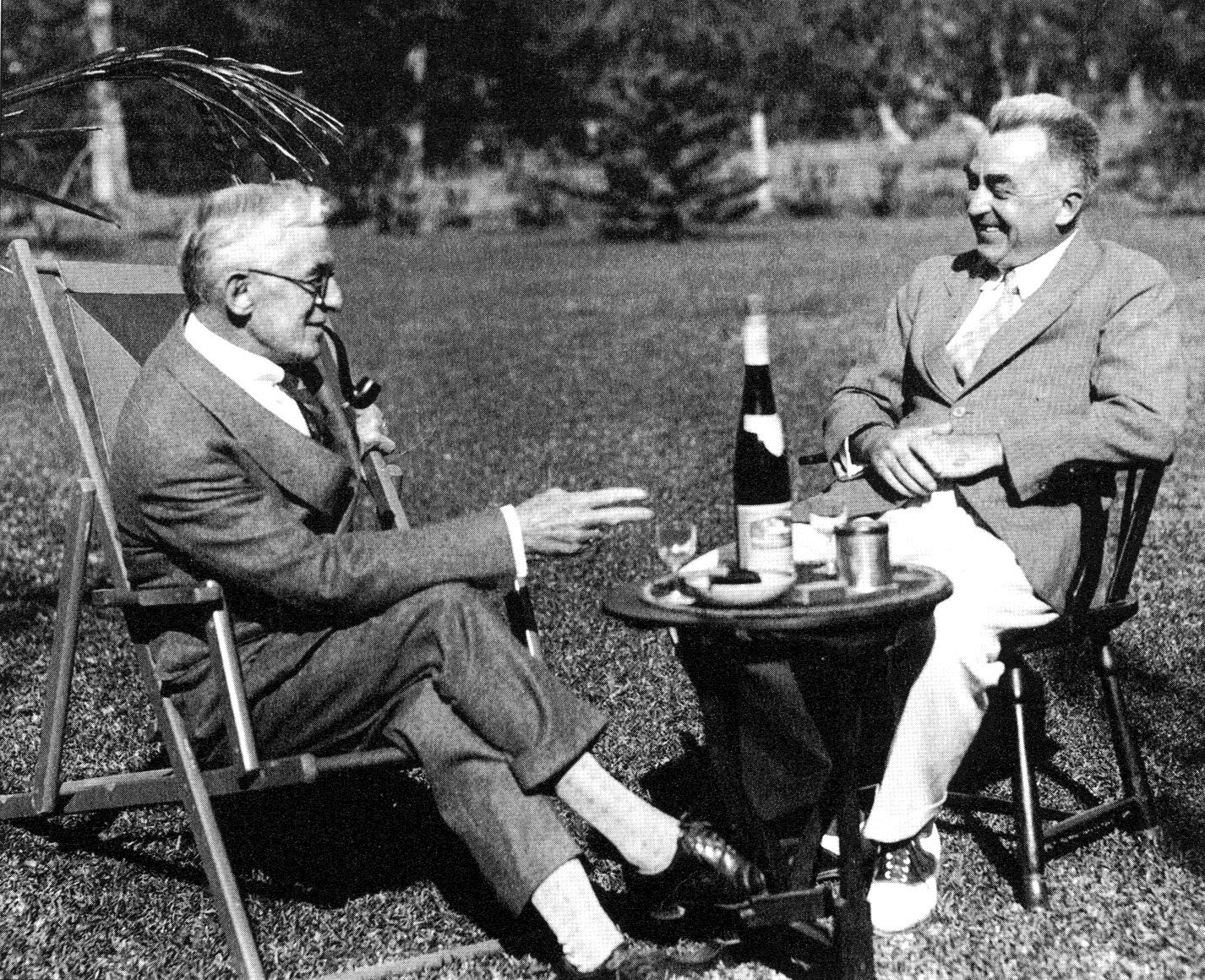

Ralph Adams Cram (left) and Raymond Hood in Bermuda, c.1930. Hood worked for Cram as a young architect; Cram designed the Pawtucket Public Library. Courtesy, Cram & Ferguson Architects

Beyond the lectures and other materials associated with the show, one can access information on Hood through the handsome 48-page catalog written by two of the show's co-curators, Prof. Dietrich Neumann and Brown doctoral student Jonathan Duval (the other curator is Jo-Ann Conklin, director of the Bell).

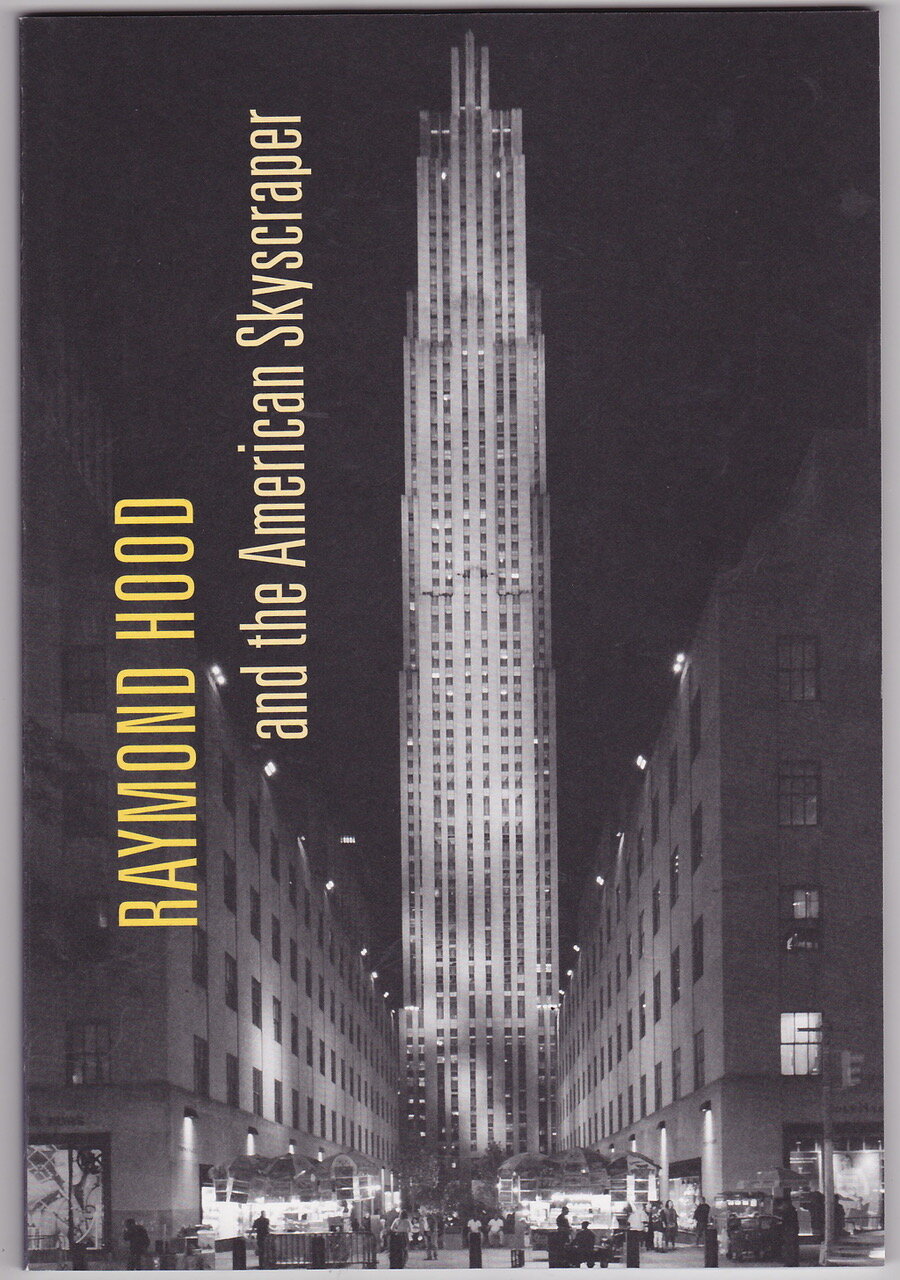

Catalog cover with Rockefeller Center, with the soaring RCA Building.

Hood would go on to design several iconic skyscrapers of the 1930s, serve as the head designer of Rockefeller Center, and would be, in Neumann's words "the most powerful architect in New York City." Significant exhibitions like this one reacquaint us with sometimes forgotten figures and force new assessments of their contributions to our cultural landscape.

RCA building at Rockefeller Center, photographed in 1933. Library of Congress.

Hood died far too young at 53. And in one of those ironies of architectural history, Modernists denigrated as too conservative the skyscraper that secured Hood's career and transformed him from dreamer to real player.

Howells & Hood, Chicago Tower. PHOTO ©Hassan Bagheri

As Neumann and Duval remind us, Hood was a struggling draftsman when he teamed up with the fashionable New York architect John Mead Howells (designer of Providence’s Turks Head Building) to enter the major international competition to build the Chicago Tribune's headquarters building in 1922. Howells and Hood beat out 262 other entrants from 23 countries with their skyscraper scheme.

I remember professors in college and graduate school ranting about the shortcomings of the Tribune Tower, labeling it "dishonest" for hiding its modern steel frame underneath a cloak of eclectic, historicist detail. It is time to acknowledge that Hood's design was the one that deserved to win, and to accept that the verticality of Gothic was wholly appropriate for such a soaring form.

Almost 100 years after that famous controversial contest, the Tribune Tower remains an absolute triumph, proudly standing in the skyscraper capital. Hood's more streamlined skyscrapers in New York – the RCA building, the Daily News Building and the McGraw-Hill Building – still inspire us, and they are especially instructive when placed against formless pieces of real estate such as Providence's proposed Fane Tower.

McGraw-Hill Building, New York, PHOTO © Hassan Bagheri

The effort that Brown has applied to the work of Raymond Hood is the sort of public service that universities offer the commonweal. Such scholarship is especially welcome now, as study of great architecture and urbanism is crucial to rebuilding after a time of pandemic.

Providence-based architecture critic and historian William Morgan has taught the history of architecture at Princeton University, The University of Louisville and Roger Williams University.

His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter