David Warsh: Is Putin responding to U.S. ‘hyper use’ of force and overreach?

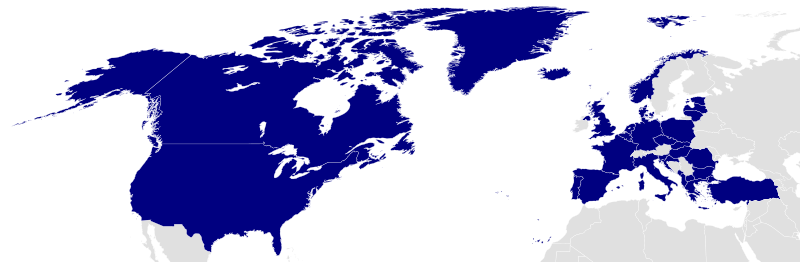

Blue indicates member states of NATO.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

With President Biden confidently forecasting a Russian “war of choice” against Ukraine –“I’m convinced he’s made the decision,” he said Feb. 18, – there is not much point in writing about it until war happens, or fails to materialize. Except to say this:

I spent some time last week leafing through books I read long ago, about an earlier “war of choice,” this one thoroughly catastrophic, as it turned – two by Robert Draper, of The New York Times, Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush, and To Start a War: How the Bush Administration took America into Iraq; one by Peter Baker, also of The Times, Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House; another by Rajiv Chandrasekaran, of The Washington Post, Imperial Lives in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone; and a fifth, by Michael MacDonald, of Williams College, Overreach: Delusions of Regime Change in Iraq.

My interest was piqued by a dispatch from New York Times Moscow bureau chief Anton Troianovski. Is NATO dealing with a crafty strategist, he asked, or a reckless paranoid? “At this moment of crescendo for the Ukraine crisis, it all comes down to what kind of leader President Vladimir V. Putin is.” He continued,

In Moscow, many analysts remain convinced that the Russian president is essentially rational, and that the risks of invading Ukraine would be so great that his huge troop buildup makes sense only as a very convincing bluff. But some also leave the door open to the idea that he has fundamentally changed amid the pandemic, a shift that may have left him more paranoid, more aggrieved and more reckless.

It seemed to me that Troianovski, and, by extension, President Biden, had neglected a third interpretation. When Putin gave a famous speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007, criticizing the U.S. for “almost un-contained hyper use of force in international relations,” he reminded listeners in his audience mainly of the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which were then underway, but his subtext was NATO expansion into Eastern Europe and Eurasia after 1993.

Perhaps, I thought, the way to think of Putin is as an accomplished rhetorician, creating a grand show-of-force, illustrated by satellite photographs and maps, with which to quietly bargain with various Ukrainian factions, while seeking to persuade other audiences that for three decades the behavior of the Unites States has been the neglected element, or, as the saying goes, “ the elephant in the room.” Perhaps the long table at whose far end Putin was photographed speaking with French President Emmanuel Macron was more symbolic of the distance that the Russian president feels from NATO negotiators than emblematic of his fear of COVID contagion.

Meanwhile, The Times last week published a story about a secretive U.S. missile base in Poland a hundred miles from the Russian border – a presence that seemed to give the lie to verbal assurances given long ago in negotiations over the reunification of Germany that NATO would expand not one inch to the East.

What if Joe Biden’s convictions about Putin’s intentions turn out to be no better than were those of George W. Bush about Saddam Hussein? When Russian forces finally attack Kyiv – or gradually return to their bases – we’ll know who was right and who was wrong. I’ll stop writing about it when they decide.

While we are hanging on the breathless daily news reports, though, Putin has managed to remind more than a few persons around the world of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, this time played out in in reverse. Was it really Pax Americana? Or more of a three-decade toot?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.