David Warsh: What George W. Bush did right

Federal Reserve System headquarters, in Washington, D.C.

— Photo by DestinationFearFan

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Before my column, called Economic Principals, goes monthly, I want to revisit what now seems to be its single most important misjudgment in forty years. While it occurred fifteen years ago, it has relevance to the present day.

The Jan, 25, 2009, edition of the weekly, “In Which George W. Bush Enters History,” I began:

George W. Bush left Washington last week amid a hail of jeers. “The Frat Boy Ships Out” headlined The Economist. “Serially incompetent,” declared the Financial Times. “Worse than Hoover,” concluded Columbia University historian Alan Brinkley.

Bush arrived in Midland, Texas, to find a cheering crowd of 20,000.

I was a little more temperate. Bush’s admirers for years had for years portrayed him as resembling Harry Truman – unpopular when leaving office, later remembered with “a tincture of admiration and regret.” A more re-illuminating comparison, I suggested, citing expert opinion, was to Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), the last president with a faith-based foreign policy.

I said nothing about the apartheid policy that Wilson, a Virginian, reinstalled; this was before the Third Reconstruction gathered steam, George Floyd (1973-2020) and The New York Times’s 1619 project. It was a pretty good column, worth reading today, emblematic of the weekly’s style, before, a year later, I began writing the book that has preoccupied me ever since.

Wilson’s case is a good illustration of the fact that every president makes so many decisions about so many polices that it is difficult, if not impossible to single out in his day the one for which he’ll be remembered decades later, depending on the decade. Bush’s great achievement grew out of two decisions he made during the final quarter of his administration.

The second half had started badly enough with his Second Inaugural Address.

[I]t is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.

Then came the Hurricane Katrina flood, the plan to privatize Social Security, the two-thousandth American death in Iraq, Vice president Dick Cheney shooting a fellow fowler during a Texas partridge hunt. An old friend dates the low point as Bush’ s attempt to appoint one of his staffers to the Supreme Court.

After that, things improved. After heavy losses in the mid-term election, Bush fired Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, turned away from Cheney in favor of Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. He appointed corporate attorney and former appellate court judge John Roberts to the Supreme Court. A year later he picked Goldman Sachs chief executive Henry Paulson as Treasury secretary.

Most important, in October 2005, Bush chose Ben Bernanke an expert on the Great Depression, to be chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Bernanke, a former Princeton University professor, had spent four years of his administration as a governor of the Federal Reserve Board, then two as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. The joke at the time was that Bush chose Bernanke because he wore white socks with his dark suits to White House briefings.

Bernanke had a relatively peaceful first year as chairman, but by 2007 was preparing measures behind the scenes to defuse or at least contro a slowly building crisis. By the summer of 2008, the banking system was on the verge of collapse. Even after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, in September, Paulson continued to argue that a combination of lending and takeovers by a consortium of big banks could resolve it. Bernanke and Timothy Geithner, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, said no. After three days, Paulson folded his hand. Government lending to stop the crisis would be required. A day of meetings with legislators followed.

And on that Friday Bush made his second crucial decision. He walked out with the others to the Rose Garden to make an out-of-the blue plea for a something called a Troubled Asset Relief Program. Nobody seemed to know quite what it might do. Never mind that five weeks of negotiation were required to clarify the matter. By October the panic had been quelled. Last-minute lending by the Fed Reserve, backstopped by the U.S. Treasury, and ten other central banks around the world, had prevented what otherwise virtually certainly would have turned into a second Great Depression had a lawsuits race to the bottom begun.

Bush got little credit for his courage. Barack Obama defeated John McCain in November and attention quickly shifted to blame, and the steep recession that had already begun. Unemployment climbed to 10 percent, not the twenty or more that had been feared in those five desperate weeks. Ahead lay Obamacare and the Tea Party.

Like the rest of the press, I mostly missed the story at the time. Bush’s admirers turn out to have been right. That was my single worst miscalculation. Second, of course, was America’s invasion of Iraq. Like most of the rest of the mainstream press, I was for the war before it was against it. It took about four weeks to change its mind.

And the significance to the present day? It is two-fold.

The first has to do with is the carom shot that today’s is war in Ukraine. Instead of committing American forces to free the world from tyranny, the U.S. has offered intelligence and arms, and otherwise depended on the willingness of Ukrainian soldiers to repel the invaders of their homeland. Tens of thousands have died.

As Fareed Zakaria writes in the current Foreign Affairs, “America shouldn’t give up on the world it made.” Mike Johnson’s willingness to risk his speakership to build a bipartisan coalition ensure that America keeps its promises, as best it can. His choice is the true beginning of the end for Donald Trump.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com

David Warsh: Is Putin responding to U.S. ‘hyper use’ of force and overreach?

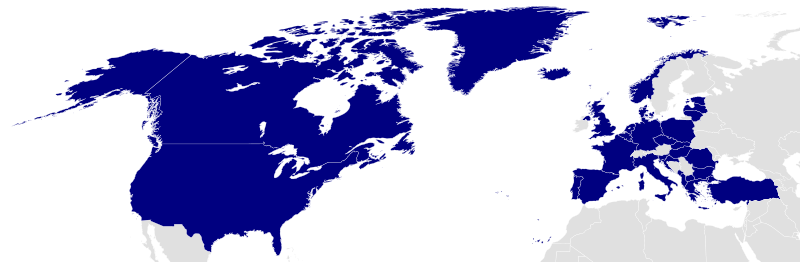

Blue indicates member states of NATO.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

With President Biden confidently forecasting a Russian “war of choice” against Ukraine –“I’m convinced he’s made the decision,” he said Feb. 18, – there is not much point in writing about it until war happens, or fails to materialize. Except to say this:

I spent some time last week leafing through books I read long ago, about an earlier “war of choice,” this one thoroughly catastrophic, as it turned – two by Robert Draper, of The New York Times, Dead Certain: The Presidency of George W. Bush, and To Start a War: How the Bush Administration took America into Iraq; one by Peter Baker, also of The Times, Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House; another by Rajiv Chandrasekaran, of The Washington Post, Imperial Lives in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone; and a fifth, by Michael MacDonald, of Williams College, Overreach: Delusions of Regime Change in Iraq.

My interest was piqued by a dispatch from New York Times Moscow bureau chief Anton Troianovski. Is NATO dealing with a crafty strategist, he asked, or a reckless paranoid? “At this moment of crescendo for the Ukraine crisis, it all comes down to what kind of leader President Vladimir V. Putin is.” He continued,

In Moscow, many analysts remain convinced that the Russian president is essentially rational, and that the risks of invading Ukraine would be so great that his huge troop buildup makes sense only as a very convincing bluff. But some also leave the door open to the idea that he has fundamentally changed amid the pandemic, a shift that may have left him more paranoid, more aggrieved and more reckless.

It seemed to me that Troianovski, and, by extension, President Biden, had neglected a third interpretation. When Putin gave a famous speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007, criticizing the U.S. for “almost un-contained hyper use of force in international relations,” he reminded listeners in his audience mainly of the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which were then underway, but his subtext was NATO expansion into Eastern Europe and Eurasia after 1993.

Perhaps, I thought, the way to think of Putin is as an accomplished rhetorician, creating a grand show-of-force, illustrated by satellite photographs and maps, with which to quietly bargain with various Ukrainian factions, while seeking to persuade other audiences that for three decades the behavior of the Unites States has been the neglected element, or, as the saying goes, “ the elephant in the room.” Perhaps the long table at whose far end Putin was photographed speaking with French President Emmanuel Macron was more symbolic of the distance that the Russian president feels from NATO negotiators than emblematic of his fear of COVID contagion.

Meanwhile, The Times last week published a story about a secretive U.S. missile base in Poland a hundred miles from the Russian border – a presence that seemed to give the lie to verbal assurances given long ago in negotiations over the reunification of Germany that NATO would expand not one inch to the East.

What if Joe Biden’s convictions about Putin’s intentions turn out to be no better than were those of George W. Bush about Saddam Hussein? When Russian forces finally attack Kyiv – or gradually return to their bases – we’ll know who was right and who was wrong. I’ll stop writing about it when they decide.

While we are hanging on the breathless daily news reports, though, Putin has managed to remind more than a few persons around the world of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, this time played out in in reverse. Was it really Pax Americana? Or more of a three-decade toot?

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Domenica Ghanem: G.H.W. Bush's racist policies recall Trump's

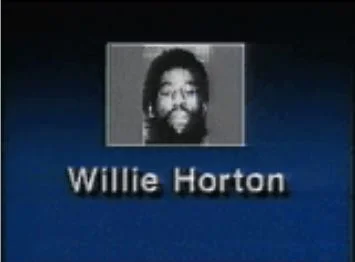

From the “Weekend Passes’’ campaign ad for George H.W. Bush’s 1988 presidential campaign.

Via OtherWords.org

As the federal government closed shop for a day of national mourning for the late President George H.W. Bush, an image of came to my mind.

It’s an ad by his supporters claiming, in 1988, then presidential candidate and Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis “allows first degree murderers to have weekend passes,” as an image of an African-American man, Willie Horton, flashes across the screen. More photos of Horton are shown, along with the words “stabbing, kidnapping, raping.”

I wasn’t even born when this ad aired in 1988. I know it because I studied it in my media classes as a classic example of how politicians stoked racist fears to link black people to crime and further a mass incarceration agenda.

Just last month, President Trump’s political team ran an ad inspired by the same race-baiting tactic. An ad so obviously racist even Fox News stopped running it. It depicts Mexican immigrant Luis Bracamontes saying he would “kill more cops,” and claims “Democrats let him into our country. Democrats let him stay.” (These claims were false.)

The ad was designed to link Central American immigrants to crime just as a caravan of asylum seekers from Honduras was headed to the U.S.-Mexico border.

As I recall H. W. Bush’s legacy, the similarities keep coming.

In 1989, Bush had the Drug Enforcement Administration lure a teenager to sell crack cocaine just across the street from the White House. They chose Keith Jackson, a 19-year-old African American high school student from Anacostia who, thanks to a very real-estate-segregated D.C., didn’t even know where the White House was.

After the incident, Bush showed this bag of crack on national television, calling for more prison funding. Jackson ended up serving eight years.

More recently, Trump has been ratcheting up fears about MS-13, a gang. He’s been using the pain and suffering of Evelyn Rodriguez, the mother of a daughter killed by a gang member, as a prop in speeches and roundtables to show people how dangerous “illegal” immigrants are. “These aren’t people,” he’s said. “These are animals.”

All the while, he’s been separating mothers and children at the border and keeping the kids locked up in detention centers.

It’s hard not to see how these two presidents employ politics cut from the same cloth. One demonizing black U.S. citizens, the other demonizing brown immigrants, all in an effort to distract from the real crime — money being funneled up to their rich friends rather than invested in public goods.

How quickly we forget.

The celebrations of the Bush legacy even extend to his son, the still living former President George W. Bush. A recent Tylt online poll asked is “Donald Trump making you finally appreciate George W. Bush?”

Almost 74 percent said they’d #RatherHaveBush. Oof.

The junior Bush’s climb in popularity isn’t thanks to establishment Republicans who wish Trump would just be a bit quieter about his racism. His favorability among Democrats is at 54 percent, compared to 11 percent in 2009.

Why do we condemn Trump but laud the Bush family? Because they weren’t as mean-sounding and could take a joke?

That’s a pretty low standard of decency for a pair of presidents who, together, killed millions in the Middle East and imprisoned millions of nonviolent drug offenders back home.

And it’s a dangerously low standard for us to sustain moving forward. If we keep forgetting or revising our history, we’re destined to repeat it with leaders who may crack a smile and use respectable language, but forge ahead with a Trump-like agenda nonetheless.

Domenica Ghanem is the media manager at the Institute for Policy Studies.