David Warsh: It may be too late but here’s a suggestion on saving print newspapers

Newspapers rolling off the press

— Photo by Knowtex

1896 ad for The Boston Globe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It may have been pure coincidence that strains on American democracy increased dramatically in the three decades after the nation’s newspaper industry came face to face with digital revolution. Then again, the disorder of the former may have something to do with the latter.

Since 2001, the last good year, daily circulation of major metropolitan newspapers has been plummeting. An edifying survey last year found that The Wall Street Journal, at the top of the field, delivered more print copies daily (697,493) than its three next three competitors combined: The New York Times (329,781), USA Today (149,233) and The Washington Post (149,040).

All but one of the top 25 newspapers reported declining print circulation year-over-year. The Villages Daily Sun, founded in 1997 in central Florida, not far north of Orlando, was up 3 percent, at 49,183, ahead of the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Is there still a market for print newspapers? Maybe, maybe not. There is probably only one good way to answer the question. I’d like to suggest a simple experiment: compete on price.

The New York Times Company bought The Boston Globe 30 years ago this week for $1.13 billion, in the last days of the golden age of print journalism. The Times ousted the Globe’s fifth-generation family management in 1999, installed a new editor in 2001, and, for 10 years, rode with the rest of the industry over the digital waterfall.

The Globe, whose 2000 circulation had been roughly 530,000 daily and 810,000 Sunday, broke one great story on the way down. Its coverage of the systemic coverup of clerical sexual abuse of minors in the Roman Catholic Church beginning in 2002 has reverberated around the world. The story produced one more great newspaper movie as well – perhaps the last — Spotlight. Otherwise the New York Times Co. mismanaged the property at every opportunity, threatening at one point to simply close it down. It finally sold its New England media holdings in 2013 to commodities trader and Boston Red Sox owner John W. Henry for $70 million.

Since then, the paper has stabilized, editorially, at least, under the direction of Linda Pizzuti Henry, a Boston native with a background in real estate who married Henry in 2009. Veteran editor Brian McGrory served for a decade before returning to column writing this year. Nancy C. Barnes was hired from National Public Radio to replace him; editorial page editor James Dao arrived after 20 years at the Times. A sustained advertising campaign and new delivery trucks gave the impression the Globe was in Boston to stay.

Henry himself showed some publishing flair, starting and selling a digital Web site, Crux, with the idea of “taking the Catholic pulse,” then establishing Stat, a conspicuous digital site that covers the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. Henry’s sports properties – the Red Sox, Britain’s Liverpool Football Club, a controlling interest in the National Hockey League’s Pittsburgh Penguins, and a 40 percent interest in a NASCAR stock car racing team, are beyond my ken.

There is, however, one continuing problem. The privately owned Globe is thought to be borderline profitable, if at all. It seems to have followed the Times Co. strategy of premium pricing. Seven-day home delivery of The Times now costs $1305 a year. Doing without its Saturday and overblown Sunday editions brings the price down to $896 for five days a week. The year-round seven days a week home delivery price for The Globe is posted in the paper as $1,612, though few subscribers seem to pay more than $1200 a year, to judge from a casual survey.

In contrast, six-day home delivery of WSJ costs $720 a year. The American edition of the Financial Times, in some ways a superior paper, costs $560 six days a week, at least in Boston. It is hard to find information about home-delivery prices for The Washington Post, now owned by Amazon magnate Jeff Bezos. But $170 buys out-of-town readers a year’s worth of a highly readable daily edition.

So why doesn’t The Globe take a deep breath and cut home-delivery prices to an annual rate of $600 or so, to bring its seven-day value proposition in line with those of the six-day WSJ and the FT? The Globe trades heavily on legacy access to wire services of both The Times and The Post; it is not clear how this would fit into such a bargain with readers. Long-time advertising campaigns would be required to make the strategy work.

That would be taking a leaf from The Times’s long-ago playbook. In 1898, facing falling ad revenues amid malicious rumors that it was inflating its circulation figures, publisher Adolph Ochs, who had bought the daily less than three years before, cut without warning its price from two cents to a penny, to the astonishment of his principal New York competitors on quality, The Herald and The Tribune. He quickly gained in volume what he gave up for the moment in revenue, raised the price a year later, and never looked back. The move has been hailed ever since as “a stroke of genius.”

Would it work today? It might. If it did, it would constitute a proof of concept, an example for all those other formerly great metropolitan newspapers to consider in hopes of creating a standard for two-tier home-delivery pricing: one price for the national dailies; a second, slightly lower price for the less-ambitious home-town sheet.

It might force The Times to cut back on its Tiffany pricing strategy, to take advantage of once-again growing home-delivery networks, and get print circulation increasing again, after two decades of gloomy decline.

Even digital publisher of financial information Michael Bloomberg might be persuaded to put his first-rate news organization to work publishing a thin national newspaper, on the model of the FT. Print newspapers have a problem with pricing subscriptions to their print daily papers. It is time for industry standards committees to begin considering the prospects.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

“Newspaper readers, 1840,’’ by Josef Danhauser

David Warsh: Bitter times —John Kerry, the Vietnam War, me and The Boston Globe

Logo of the controversial anti-Kerry Vietnam veterans group in the 2004 presidential candidate

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

What does a top newspaper editor owe his publisher? The press critic A. J. Liebling famously wrote: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Tired of arguing with a friend about the implication of that dictum, I threw up my hands a year ago and walked away. Since then, interest in the question has been rekindled. I decided to re-engage

The particular case that interests me has to do with the role of The New York Times in the 2004 presidential election. It was then that the first collision occurred between mainstream news media and crowdsourcing on the internet: The derisive Swift Boat Veterans for Truth vs. the John Kerry campaign. Did the presidency hang in the balance? There is no way of knowing. George W. Bush received 50.7 percent of the popular vote, against 48.3 percent for Kerry; in the Electoral College, the margin was slightly wider, 286 to 251.

In at least in one respect, crowdsourcing seemed to have won its contest that year. More news about dissension within the Swift Boat ranks appeared first on the Web during the second half of the year, rather than in newspapers. As Jill Abramson notes in Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts (Simon & Schuster, 2019), the newspaper business changed after that.

I followed what happened in 2004 because eight years earlier, I had become involved in what turned out to have been its quarter-final match. In 1996, Kerry, the junior U.S. senator from Massachusetts, was running for re-election to a third term against a popular two-term governor, William Weld. Kerry decisively defeated Weld, sought the Democratic vice-presidential nomination in 2000, then secured the Democratic Party’s nomination in 2004 to run against Bush.

Until 1996, Kerry was known to the national public mainly as a critic of the Vietnam War. The ‘80s, which began with the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan and Ronald Reagan’s election to his first term, had changed attitudes toward America’s experience in Vietnam. Though first elected in 1984 – on, among other things, a promise to stop U.S .atrocities in Nicaragua, – Kerry’s 1996 senatorial campaign was the first one in which he sought to tell the story of his war in Vietnam. He gave highly personal accounts of his service to Charles Sennott, of The Boston Globe, and to James Carroll, of The New Yorker, which appeared a month before the election. In reading them, I was struck by certain inconsistencies in the senator’s accounts – in particular, by the relatively short time he had spent in Vietnam.

I was then a columnist on the business pages of The Globe, writing mostly about economics and its connection to politics, but for a year (1968-69), as a second-class petty officer in the U.S. Navy, I had been a Pacific Stars and Stripes correspondent, based in Saigon, and, for a year after that, a stringer for Newsweek magazine.

After Kerry boasted of his service and disparaged Weld for not having gone to that fight, I wrote a column on Monday for Tuesday, Oct. 22, that was headlined “The war hero.” In the course of my reporting, a member of Kerry’s Swift Boat crew, who had been put in touch with me by the campaign, confided in the course of a long conversation a detail that hadn’t appeared before. A second veteran, a former Swift Boat officer-in-charge, phoned the paper to offer additional details. I requested permission to draft a follow-up column, and received it.

A year ago, I told my story about how that second column came to be written. Below, I put into the record a parallax account of the key events of that week, in the form of a November 1996 letter from former Boston Globe editor Matthew Storin to a strident critic of The Globe’s coverage of Kerry in this instance. I include the letter to which he was responding as well below. They are long and painful to read, and unless you, too, are interested in 2004, you can skip them.

I am writing all of this now for two reasons. I learned last year that having retired from the newspaper business, Marty Baron is writing a book. Collision of Power: Trump, Bezos, and The Washington Post (Flatiron) is said to be about his eight years as executive editor of The Post, beginning just after Amazon founder Jeff Bezos purchased the paper from the Graham family. That makes Baron an expert on the central topic here; all the more so since in 2011, he was considered one of the three likeliest candidates to replace executive editor Bill Keller in the top news job at The Times, according to Jill Abramson, who ultimately got the job. I am eager to see what Baron says about The Globe’s 2004 book about Kerry, so I decided to put on the table the first of the cards that I possessed.

I also want to express the conviction that the resounding success of the tactics Kerry employed in 1996 probably cost him the presidency in 2004. During the week in the fall of ‘96 that we waited for the campaign’s reply to questions raised by “The war hero” column, we accumulated several new bits and pieces of information. Had his staff kept its promises, we would have asked questions about them, but I doubt that I would have written a second column, and certainly not the second column that appeared. Probably we would have waited until after the election, perhaps long after the election, to begin to resolve the questions. Meanwhile, Kerry might have learned how to talk about the issues that would be so starkly raised in 2004.

Instead, a hastily arranged Sunday rally, as Storin’s letter makes clear, was the equivalent of an ambush. Kerry and others, including Adm. Elmo Zumwalt, Commander of Naval Forces in Vietnam when Kerry had been there, assembled from around the country and appeared in the Boston Navy Yard to fiercely denounce the second column, barely 12 hours after it appeared in print. The effects were blistering. With the election 10 days away, The Globe covered the rally and otherwise put the story aside.

I received a copy of Storin’s letter to the critic soon after the election, via interoffice mail. In the five years I remained at The Globe, I was never asked by senior editors about what I had learned. The news business was different in those days. Newspapers were still regnant, but their owners embraced differing principles and possessed different points of view. The Globe had been purchased by New York Times Co., in 1993. Under a standstill agreement, the paper was still managed by the Taylor family in 1996, as it had been for 125 years. Even then, the implications of the sale were beginning to come clear. NYT Co. president Arthur O. Sulzberger, Jr. fired Benjamin Taylor as. Globe publisher in 1999, and replaced Storin with Baron in mid-2001.

Kerry considered questions about his experiences in Vietnam, asked in the rough and tumble of the news cycle, to be illegitimate; I and my editors considered them appropriate in the circumstances. None of us, I think, would have felt any compulsion to publish that second column had the campaign kept its promises. We’ll never know. But in refusing to respond, and attacking instead, Kerry had effectively ruled the questions out of bounds.

Kerry’s success in 1996 may have bred over-confidence going forward. The next eight years produced little news on these matters. The historian Douglas Brinkley wrote his campaign biography, Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War (William Morrow, 2004). By the time it appeared, a whole new wing of the news industry had gained an audience – Rush Limbaugh, the Drudge Report, the Fox News Network, Bill O’Reilly and Andrew Breitbart.

When the same ambush tactics the Kerry campaign employed against The Globe were used against him in May 2004 by the organization calling itself Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, it was too late to disarm. Kerry toughed it out. Bluster and evasion had become a habit.

. ••

“November 6, 1996

“John M. Hurley, Jr., 78 Longfellow Road, Wellesley. MA 02181

““William 0. Taylor, Chairman; Benjamin B. Taylor, President; Matthew V. Storin, Editor: The Boston Globe

Gentlemen: ‘

“What has happened to The Boston Globe? What has happened to the proud, 124-year tradition of impeccable journalistic standards?

“David Warsh has disgraced himself. He has shamed The Boston Globe, he has stained the profession you cherish.

“I am a Vietnam veteran, a 26-year friend of John Kerry, and a 4-decade long fan of the Boston print media. (My father was a Boston news photographer for 43 years – 29 with The Boston Post, 2 freelancing, 12 with the Globe – and he instilled in his children an unyielding admiration for the Boston print media.)

“But in 40-plus years of close observation of Boston newspapers, I have never seen a more despicable, more vicious, more baseless attack than David Warsh’s columns on John Kerry.

“Without any foundation whatsoever, without a single witness contradicting events that took place 27 years ago, without a shred of physical or documentary evidence, Warsh levels the single, most vile hatchet job that I have ever seen.

“Where is Warsh’s evidence to contradict these witnesses, where is the substantiation for his vicious speculation? There is none. Not one word. He speculates about the most heinous war clime imaginable – the commission of murder in order to secure a medal – and offers nothing in support of his speculation. Not a single witness. Not a statement. Not a document. Nothing. It is simply Warsh’s own personal, vicious speculation.

“Even a ‘decorations sergeant,’ if he has an ounce of objectivity, if he has an ounce of integrity, is capable of putting this incident into the context of a firefight: incoming B-40s. enemy fire, from both shorelines, third engagement of the day. stifling heat. deafening noise. screaming, shouting, adrenaline-driven chaos. Sheer mind-numbing chaos. Kerry and his crew were trained to do one thing in order to save their lives: react, react, REACT. Lay down a base of fire, or die. It was that simple. Even a ‘decorations sergeant’ understands that. But if you have no objectivity, if you have no integrity, you don’t put the incident into context. you write of war crimes instead.

“And what of that dead VC? According to Warsh, he was Just a tourist on holiday. ‘The one thing that seemed hard to abide was a grandstander. A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’ SAY … THAT .., AGAIN. ‘A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’

“A VC soldier … in the midst of a firefight … armed with a B-40 rocket … aimed at the crew of a U.S. Navy swift boat – and Warsh sides with the dead VC. An unlucky young man, finished off for the sake of a Silver Star by a grandstander.

“Who does David Warsh think he is? What right does he have to casually, callously, with utter disregard for the facts presented to him destroy a person’s reputation. Their character. their integrity, their honor?

“And you let him do it. Twice.

“Where are your journalistic standards. Where is your outrage. Where is your moral indignation. Where is your decency. Where ls your fairness? Do you really believe that Warsh’s vicious conjecture rises to the level of fair, objective comment? Are Warsh’s columns the stuff of which you want your newspaper judged?

“John Kerry’s honor, his crew’s honor, is intact. What of the Globe’s?

“It is important to point out that Warsh’s reporting is replete with errors. Warsh engages in the vilest character assassination imaginable, and he doesn’t even get basic facts right. In any newsroom I have ever visited ‘getting the story right’ is worn like a badge of honor. Warsh didn’t even try.

“Relying solely on personal conjecture (‘What’s the ugliest possibility? ….’) and vicious innuendo (‘Tom Bellodeau (sic) says he was awarded a Bronze Star … but I have been unable to find a copy of the citation.

“Warsh proceeds to trash the honor of Kerry, his crew, and indeed every veteran who has ever been awarded a medal for bravery.

“There is not one word of substantiation in Warsh’s diatribe. There is no foundation, no witness, no evidence, no document that contradicts what has been said or written about Kerry’s war record. Yet Warsh dangles before the reader the most heinous speculation imaginable: that Kerry murdered a wounded, helpless enemy soldier in order to win a Silver Star for himself. An unspeakable crime, yet Warsh offers nothing to substantiate it. The allegation is solely Warsh’s own vicious, character-assassinating conjecture.

“And you let him publish it. Twice.

“Warsh advances his vicious speculation even though there are rock-solid statements and documents to the contrary, statements and documents that completely contradict his spurious, hate-filled conjecture:

“Belodeau told Warsh: ‘When I hit him, he went down and got up again. When Kerry hit him, he stayed down.’

“Medeiros told the Globe’s Barnicle: ‘I saw a man pop-up in front of us. He had a B-40 rocket launcher, ready to go. He got up and ran for the tree line. I saw Mr. Kerry grab an M-16 and chase the man. Mr. Kerry caught the man in a clearing in front of the tree line and he dispatched the man just as he turned to fire the rocket back at the boat…I haven’t seen or talked with Mr. Kerry since 1969, but I admired him them and I admire him now. He saved our lives.’

“Kerry’s Silver Star citation, awarded for ‘conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action,’ signed by Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, states that the enemy soldier had a B-40 rocket launcher ‘with a round in the chamber.’

“Warsh quoted Kerry (from the Carroll piece): ‘It was either going to be him or it was going to be us. It was that simple. I don’t know why it wasn’t us – I mean to this day. He had a rocket pointed right at our boat.’

“Warsh misspelled Tom Belodeau’s name 13 times.

“Warsh referred to Belodeau as the ‘rear gunner’: Belodeau was the forward gunner.

“Warsh reports that Keny was assigned to a boat ‘whose skipper had been killed’; the skipper was not killed, he was wounded, and is alive today.

“Warsh refers to ‘heavy 50 mm machine guns’: they are .50-caliber machine guns. ‘50 mm machine guns’ are laughable; a reporter with even a cursory attempt at accuracy would have caught the error instantaneously.

“Warsh asks: ‘But were there no eyewitnesses?’ There were at least three: Tom Belodeau, Mike Medeiros. John Kerry. All were quoted in the Globe. But Warsh decided that from a distance of 27 years he knew better than they what happened that day. He ignored what they said, he opted instead to write his own personal, vicious, unsubstantiated conjecture.

“When you engage in character assassination. you have an absolute obligation to ‘get it right.’ Warsh didn’t even try. Why was he in such a hurry to get his hate-filled column into the paper?

“You have always been an aggressive, but responsible newspaper. You have never, until now, stooped this low. So, how did these columns happen? How did they get into your newspaper?

“Your journalistic integrity has been trashed by David Warsh, and the editors that OK’d these columns for publication. These columns were not a close call. These columns were flagrantly out of line. 124 years of journalist integrity has been trashed. It will take you years, if not decades. to recover from the stain of these columns.

“Hang your head in shame, Boston Globe. Hang your head in deep, deep shame.

/s/ John Hurley

“P.S. to Mr. Storin:

“And what of you, Mr. Storin?

“Did Warsh act entirely on his own? Does the Globe’s policy of complete freedom to its columnists mean that no editor even questioned Warsh about the foundation of his columns? Even when Warsh’s columns are totally outside his field of expertise? Did no editor request even minimal substantiation of his vicious speculation: a witness, a document, a statement? Anything at all?

“Does the Globe’s policy of complete freedom to its columnists extend to baseless, personal character assassination? Did you and the editors that work for you fail to see a pattern of vicious, personal attacks by Warsh?

“‘… there is,” Warsh wrote, ‘a good, strong, dispassionate reason to prefer Bill Weld to John Kerry.’ Fair enough. He’s entitled to endorse whomever he wants to. But then the pattern of attacks began:

“Warsh, Oct. 15, 1996: ‘he was acquired by John Heinz’s widow in a tax-exempt position-for dollars swap.’

“Warsh, Oct. 22, 1996: ‘The one thing that seemed hard to abide was a grandstander. A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’

“Warsh, Oct. 27, 1996: ‘What’s the ugliest possibility? That behind the hootch, Kerry administered a coup de grace to the Vietnamese soldier – a practice not uncommon in those days but a war crime nevertheless, and hardly the basis for a Silver Star.’

“A recurring pattern of vicious, unsubstantiated personal attacks. Is this what constitutes fair and objective comment under the Globe’s current journalistic standards?

“The very day Mike Medeiros was quoted in the Globe saying Kerry ‘saved our lives,’ you gave Warsh additional space, and let him – without a single witness, without a single document, without a single supporting statement – viciously speculate about a war crime, for the very act that Medeiros said saved their lives. A war crime? Admiral Zumwalt, the highest ranking Naval officer in Vietnam, stated that John Kerry’s heroism that day was worthy of the Navy Cross, the second highest medal for bravery that our country awards. (But Zumwalt recommended a Silver Star instead, because he wanted to expedite the awards ceremony and boost the morale of his troops who were taking heavy casualties at the time).

“Every witness that has spoken, every document that exists. every shred of evidence that has been found states that Kerry acted selflessly, with extraordinary heroism. Yet Warsh, without foundation, without any substantiation whatsoever, conjectures about a war crime. And you print it. Is that the journalistic standard by which you want your reading public, your fellow journalists across the country, your publishers, to judge you and The Boston Globe?

“To top off this lame, pathetic performance by you and your editors, you go on television and dismiss Warsh’s columns, saying, ‘I thought in the long run it might be favorable for Kerry.’

“Vicious, unfounded character assassination ‘might be favorable’? Ludicrous, laughable, stupid, sick.

“The basic test of character, Mr. Storin – for a man or a newspaper – is to be able to say, in the face of adversity, ‘We were wrong, extremely wrong.’ “You, The Boston Globe, and David Warsh have failed that test, egregiously.’’

“November 13, 1996

“Mr. John M. Hurley, Jr., 78 Longfellow Road, Wellesley, MA 02181

“Dear Mr. Hurley:

“Your thoughtful letter was very painful to read. You made some very harsh charges, most of which I feel were not in the same context with the decision that I was faced with in allowing publication of the David Warsh column. Nearly three decades after a signal event in the career of our junior US Senator, I had a column with a seemingly new version of events and no one willing to come forward to explain it, despite our holding the column for three days. In the midst of an election campaign, to kill such a column under those circumstances was something I could not defend.

“Here is the chronology of events that led to my decision:

1. “Warsh says he has turned up this odd statement by Belodeau that does not appear to square with the previous He writes a first version of the column that lands on our desks on Wednesday. Because we are getting closer to the election, we consider publishing it on the following day, rather than waiting until the next of his regular column dates.

2. “I telephoned John Marttila, one of Kerry’s senior advisers, and urge him to have the senator talk to Warsh. I assume the discrepancy can be straightened out. John indicates that it is next to impossible to reach the senator, who is on his way to the debate in Springfield.

3. “I tell my editing colleagues Wednesday night that we must hold the column until we are able to (a.) reach Belodeau for additional clarification and (b.) reach Senator Kerry.

4. “Tom Vallely calls me Thursday morning and discusses the Warsh I tell him what Belodeau has said (or perhaps he already knew), and he says, in pretty much these exact words, “We have no problem with that. We have no problem with that/ and explains that the guy Belodeau hit got back up and appeared still able to fire his weapon. Frankly, I am relieved to hear this because it’s a plausible explanation and we can avoid even addressing the issue anew. Vallely says he will produce “his (Kerry’s) commanding officer. I got the impression that Tom would also help get Belodeau back to Warsh and possibly the senator himself, though on the latter point I may have been mistaken. I think Tom might have said earlier that the senator would not talk to Warsh. I had to leave for a journalism conference on Long Island, but at this point I am confident that the column will not be a problem.

5. “Late Friday, I ask to have the column faxed to me. I am very surprised to learn that neither Belodeau nor Kerry has offered anything to Warsh and that the officer has said he was not an eye witness. The New Yorker quote is also puzzling to me. Yet I feel that Warsh deals with the incident with some caution, offering two possibilities. It’s an effort to examine an important incident in the military career of a major public figure who has chosen for some reason — and that is fully his right — to not answer the columnist’s questions.

“From the remove of hindsight, it is now obvious that Senator Kerry chose prior to publication to use the column (of which through Vallely and others he probably had accurate knowledge) to his own advantage. Not only is that his privilege, but it appears to have been good politics. In any event, it probably would not have been possible to get Admiral. Zumwalt here between early Sunday morning and the late afternoon press conference, so that is my assumption.

“Frankly, the column probably would have disappeared without a trace otherwise. After reading it on Friday, I told our executive editor, Helen Donovan, ‘I think this is worth 1,000 votes for Kerry.’ Given your letter, you are probably incredulous at that, but I felt it humanized the senator in a way that has often not been the case in his career. Of course, I saw the negativity in it, but I thought readers would make their own judgments about the issues – as they do with all our opinion columns.

“As to an apology, I would first like to outline what the paper has done in print. We published the story of the press conference on page one Monday, including Belodeau’s explanation for his remark and his account of the battle as well as the testimony of Medeiros, whom our reporter spoke to by telephone. Obviously this piece was presented more prominently than the original column. We then published an op-ed piece by James Carroll, criticizing us in very harsh terms. It is part of our culture to publish a column such as Carroll’s just as it is to publish a column such as Warsh’s. William Safire writes a half dozen speculative columns a year that are as harsh to Bill Clinton as Warsh’s was to Senator Kerry. When was the last time you saw an op-ed piece in the Times that criticized the Times? Finally, we published a piece by our Ombudsman that, like Carroll, said the column should not have been published.

“I personally may regret that the column ran, but, given the same set of circumstances again, I would not kill the column. I have to make those decisions in the context of columns we have run in the past and might run again in the future. We were in the middle of a tough campaign, Belodeau had made a statement that seemed at odds with anything previously published, and despite waiting three days, no one had come forth on behalf of Senator Kerry to explain it. I agree that it’s a sign of character to admit when you are wrong and, in some ways, that would be easier to explain than what I am trying to say here. I believe David Warsh may address his own personal feelings in a future column and, possibly, in a conversation with Senator Kerry if that is possible.

“It pains me to read that Senator Kerry feels this was a low point in his life. I am certain of one thing: It would have been avoided if he had given a statement to Warsh as we had asked. His failure to respond — even if he wanted to call a press conference in advance — took out of my hand a major argument for changing or killing the column (though I believe Warsh would have treated the subject much differently). Your citation of the Medeiros quote is interesting. The campaign obviously chose to make Medeiros available to another columnist, rather than reply directly to Warsh. That’s another legitimate political decision by the Kerry campaign, but it didn’t help with the decision I had to make on Friday evening (deadlines are earlier for Warsh’s column than for Barnicle’s). I understand that the senator and some of his advisers felt wary of dealing with Warsh, but Tom Vallely and John Marttila knew that I had personally involved myself in the issue and could have phoned me back at any time between Thursday morning and Friday night. Though I was out of town, I was easily reachable.

“I do regret — and they are inexcusable — the relatively minor but not insignificant “inaccuracies in Warsh’s column that you cited.

“In closing, I would like to note that you are a longtime friend of Senator Kerry. I understand you may have even played a role in the campaign’s effort to deal with the Warsh column. I am neither a friend nor supporter of John Kerry nor Bill Weld. I do everything in my power, in terms of social relationships, to put myself in a position to make dispassionate decisions as a journalist. I accept that you are upset with us, but I hope you will sometime reread your letter and recognize that you made some emotional charges that were not justified.

“Sincerely

/s/ Matthew V. Storin’’

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

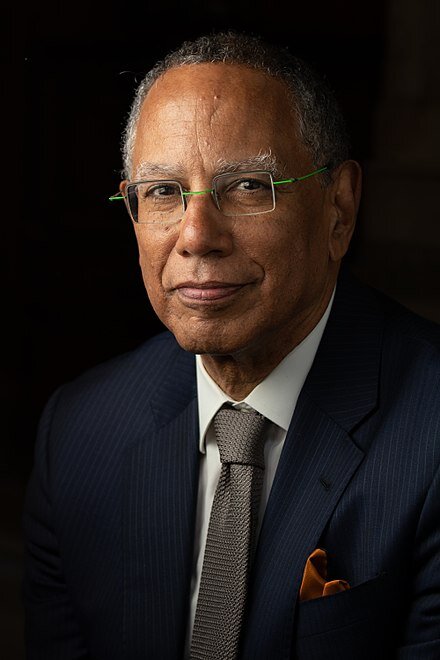

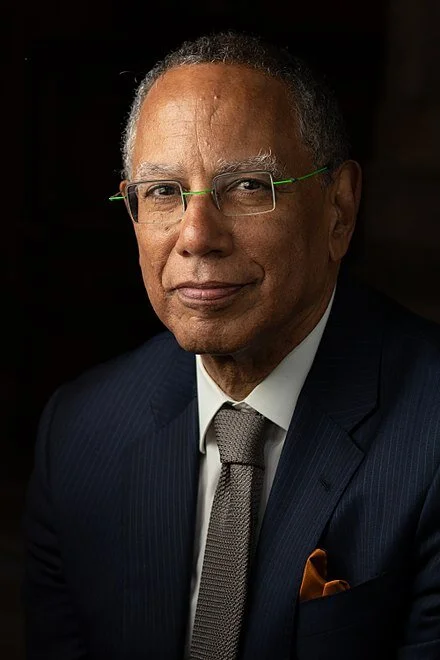

David Warsh: Of sportswriters, race and great news publications

New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Because it was August, I was reading Tall Men, Short Shorts, the 1969 NBA Finals: Wilt. Russ. Lakers. Celts, and a Very Young Sports Reporter (Doubleday, 2021). Leigh Montville was one of the many excellent sports columnists at The Boston Globe in the twenty years that I was there, somebody whom I always read no matter who or what he was writing about. After he was unreasonably refused an exit as columnist from the ghetto of sports, he left the paper for Sports Illustrated, where he wrote extended features and the back-of-the-magazine column for many years. He wrote eight books along the way. Tall Men, Short Pants is his ninth, a summing-up of much he learned about life in a fifty-year career as a journalist.

I’d been alerted to the book by The Globe’s former long-time managing editor, Thomas F. Mulvoy, who wrote about it in the Dorchester Reporter. At one point, Mulvoy says:

In a section that comes off the page with a sharp edge of sadness, Montville redresses himself (for the umpteenth time, his words suggest) for his silence at the press table when the Celtics played the Knicks in New York earlier in the season. A Globe colleague sitting next to him gave vent to his bigotry by loudly and repeatedly using the N-word while talking about the game being played in front of them. [Montville] writes: “I have thought for all these years of the things I should have done. I should have told [him] to shut up. Right away, I should have done that. If he didn’t shut up, I should have grabbed him, done something. … I should have reported all this to someone at the Globe on our return. I should have decided never to talk to him again. I should have done any of this stuff. I did nothing”

The 26-year-old Montville, who is White, served as no more than witness that day – the book reveals how he learned that his Globe colleague was deliberately baiting another Globe sportswriter, a well-known liberal, nearby – only much later affording a glimpse of the fractious mood of the nation in 1969. Montville attended his colleague’s wake thirty years later. Otherwise, he imaginatively covered changing attitudes about race in America, in columns and books, including Manute: The Center of Two Worlds (2011), and Sting like a Bee. Muhammad Ali vs. the United States of America, 1966-1971 (2017). Sports has done more than its share, and better than Hollywood, to illuminate rapidly changing stereotypes of race and class in the last fifty years. Montville was alert to the story every step of the way.

Reading Tall Men, Short Pants brought into focus a project of The New York Times of which I gradually became aware over the last couple of years.

I do not mean the paper’s scrutiny of the killings of Black men and the occasional Black woman by Whites, mostly police officers, before George Floyd was murdered by Officer Derek Chauvin, in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, though even now, thanks to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, it seems important to remember their names.

(Those whose stories made the front pages include Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Fla; Eric Garner, in Staten Island, New York; Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Mo.; Walter Scott, in North Charleston, S.C.; Philando Castile, in St. Paul; Stephen Clark, in Sacramento, and Breonna Taylor, in Louisville.

Nor do I mean the special issue of the magazine called The 1619 Project, the Times’s coverage of the debate over Critical Race Theory, or the series of essays by critic-at-large Wesley Morris that earlier this year was recognized with a Pulitzer Prize. I have in mind something less concrete but ultimately even more eye-opening, at least to me.

I am thinking of a surge of ordinary news stories about contributions to American culture by African-American citizens. These stories appeared in unusual numbers, day after day, over the course of the last eighteen months. In the trade, this kind of display is called ROP, or run of the paper, with stories placed anywhere in the paper at the option of an editor – world, U.S., politics, NY, business, opinion, tech, science, health, sports, arts, books, style, food, travel, real estate, obituaries. The surge was as unmistakable as it is difficult to describe. Instead of data, I have only personal experience of it, to which I aim to testify here, briefly.

I scan the print editions of The Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each morning at home, glance online at Bloomberg and study the story list of The Washington Post when I reach the office. In the evening, I read and clip (or print) whatever is most important to me. The differing trajectories of these five great English-language news organizations in the thirty years since the Internet emerged as a public communications medium has been fascinating, but that is a subject for another day. For now it is enough to say that The Times remains the most ambitious among them, more sparkling than ever in its aspirations.

It was the morning scanning of The Times that first produced the effect. So relentless had its coverage of Blacks newsmakers and their concerns become over the last year that one day it dawned on me what The Times had achieved. Some of the stories made big impressions. Others seemed peripheral, at least to my interests. I discussed the experience with my friend, Vincent McGee, who described it thus: “I first noticed it with obituaries, some current – mainly arts, music and sports – and others ‘catch ups’, often of Black women lost in history.”

By distorting its usual budget of stories – not much, mind you, this was only a surge – the newspaper’s editors had given me, a White reader, the feeling of somehow being unimportant. For some fleeting part of the day, I felt as many Black readers must feel most days, oppressed by the relentless attention The Times paid to the Other. This was showing, not telling, how it felt to be left out. It showed, too, what it meant to be included in. As an exercise in good newspaper editing, I will never forget it.

How had the decision to reorient the coverage been made? Anyone who knows anything about newspapers understands that inspiration comes from the bottom up. Orders are given, of course; stories are assigned, or turned back for more work. There are countless meetings, discussions, bull sessions, retreats. Word gets around. Better to say that a curiosity about race, gender, ethnicity and discrimination had been authorized at The Times as long ago as the Nineties, then encouraged, becoming wide-ranging, before coming to a low boil in 2020.

The Times’s executive editor is Dean Baquet, who was born in 1956. He is a consummate newspaperman, having started working in New Orleans even before graduating from Columbia University, in 1978. He moved from The Times-Picayune, in New Orleans, to the Chicago Tribune in 1984, where he won one Pulitzer Prize, and just missed another, before joining TheTimes, in 1990. Tribune Co. hired him back in 2000 to serve as managing editor of its newly acquired Los Angeles Times; he replaced John Carroll as editor in 2006 but was quickly dismissed after opposing newsroom budget cuts. He returned to The Times later that year as its Washington bureau chief, became its managing editor in 2011, and succeeded Jill Abramson in the top newsroom job in 2014.

Baquet is also a Black man, the fourth of five sons of a successful New Orleans restaurateur. Many years will be required to hash out all that has happened on his watch, some of it under the heading of “woke.” Baquet will write a book. Culture wars will continue. The equitable distribution of attention – of “play” – will become the next editor’s problem. Baquet turns 65 later this month; he will retire next year.

Leigh Montville won the Associated Press Sports Editors Red Smith Award in 2015; he never got out of the sportswriting ghetto, but he nevertheless became one of the finest columnists of his generation, pure and simple. Dean Baquet broke race out of the newspaper ghetto and made it ROP, maintaining news values evolved by the modern profession. He will enter history books as one of The New York Times’s greatest editors. Both men made the most of their opportunities.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Of The Globe, John Kerry, Vietnam and my column

An advertisement for The Boston Globe from 1896.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It has taken six months, but with this edition, Economic Principals finally makes good on its previously announced intention to move to Substack publishing. What took so long? I can’t blame the pandemic. Better to say it’s complicated. (Substack is an online platform that provides publishing, payment, analytics and design infrastructure to support subscription newsletters.)

EP originated in 1983 as columns in the business section of The Boston Sunday Globe. It appeared there for 18 years, winning a Loeb award in the process. (I had won another Loeb a few years before, at Forbes.) The logic of EP was simple: It zeroed in on economics because Boston was the world capital of the discipline; it emphasized personalities because otherwise the subject was intrinsically dry (hence the punning name). A Tuesday column was soon added, dwelling more on politics, because economic and politics were essentially inseparable in my view.

The New York Times Co. bought The Globe in 1993, for $1.13 billion, took control of it in 1999 after a standstill agreement expired, and, in July 2001, installed a new editor, Martin Baron. On his second morning on the job, Baron instructed the business editor, Peter Mancusi, that EP was no longer permitted to write about politics. I didn’t understand, but tried to comply. I failed to meet expectations, and in January, Baron killed the column. It was clearly within his rights. Metro columnist Mike Barnicle had been cancelled, publisher Benjamin Taylor had been replaced, and editor Matthew Storin, privately maligned for having knuckled under too often to the Boston archdiocese of the Roman Catholic Church, retired. I was small potatoes, but there was something about The Globe’s culture that the NYT Co. didn’t like. I quit the paper and six weeks later moved the column online.

After experimenting with various approaches for a couple of years, I settled on a business model that resembled public radio in the United States – a relative handful of civic-minded subscribers supporting a service otherwise available for free to anyone interested. An annual $50 subscription brought an early (bulldog) edition of the weekly via email on Saturday night. Late Sunday afternoon, the column went up on the Web, where it (and its archive) have been ever since, available to all comers for free.

Only slowly did it occur to me that perhaps I had been obtuse about those “no politics” instructions. In October 1996, five years before they were given, I had raised caustic questions about the encounter for which then U.S. Sen. John Kerry (D.-Mass.) had received a Silver Star in Vietnam 25 years before. Kerry was then running for re-election, I began to suspect that history had something to do with Baron ordering me to steer clear of politics in 2001.

• ••

John Kerry had become well known in the early ‘70s as a decorated Navy war hero who had turned against the Vietnam War. I’d covered the war for two years, 1968-70, traveling widely, first as an enlisted correspondent for Pacific Stars and Stripes, then as a Saigon bureau stringer for Newsweek. I was critical of the premises the war was based on, but not as disparaging of its conduct as was Kerry. I first heard him talk in the autumn of 1970, a few months after he had unsuccessfully challenged the anti-war candidate Rev. Robert Drinan, then the dean of Boston College Law School, for the right to run against the hawkish Philip Philbin in the Democratic primary. Drinan won the nomination and the November election. He was re-elected four times.

As a Navy veteran, I was put off by what I took to be the vainglorious aspects of Kerry’s successive public statements and candidacies, especially in the spring of 1971, when in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relation Committee, he repeated accusations he had made on Meet the Press that thousands of atrocities amounting to war crimes had been committed by U.S. forces in Vietnam. The next day he joined other members of the Vietnam Veterans against the War in throwing medals (but not his own) over a fence at the Pentagon.

In 1972, he tested the waters in three different congressional districts in Massachusetts before deciding to run in one, an election that he lost. He later gained electoral successes in the Bay State, winning the lieutenant governorship on the Michael Dukakis ticket in 1982, and a U.S. Senate seat in 1984, succeeding Paul Tsongas, who had resigned for health reasons. Kerry remained in the Senate until 2013, when he resigned to become secretary of state. [Correction added]

Twenty-five years after his Senate testimony, as a columnist I more than once expressed enthusiasm for the possibility that a liberal Republican – venture capitalist Mitt Romney or Gov. Bill Weld – might defeat Kerry in the 1996 Senate election. (Weld had been a college classmate, though I had not known him.) This was hardly disinterested newspapering, but as a columnist, part of my job was to express opinions.

In the autumn of 1996, the recently re-elected Weld had challenged Kerry’s bid for a third term in the Senate, The campaign brought old memories to life. On Sunday Oct. 6, The Globe published long side-by-side profiles of the candidates, extensively reported by Charles Sennott.

The Kerry story began with an elaborate account of his experiences in Vietnam – the candidate’s first attempt. I believe, since 1971 to tell the story of his war. After Kerry boasted of his service during a debate 10 days later, I became curious about the relatively short time he had spent in Vietnam – four months. I began to research a column. Kerry’s campaign staff put me in touch with Tom Belodeau, a bow gunner on the patrol boat that Kerry had beached after a rocket was fired at it to begin the encounter for which he was recognized with a Silver Star.

Our conversation lasted half an hour. At one point, Belodeau confided, “You know, I shot that guy.” That evening I noticed that the bow gunner played no part in Kerry’s account of the encounter in a New Yorker article by James Carroll in October 1996 – an account that seemed to contradict the medal citation itself. That led me to notice the citation’s unusual language: “[A]n enemy soldier sprang from his position not 10 feet [from the boat] and fled. Without hesitation, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Kerry leaped ashore, pursued the man behind a hootch and killed him, capturing a B-40 rocket launcher with a round in the chamber.” There are now multiple accounts of what happened that day. Only one of them, the citation, is official, and even it seems to exist in several versions. What is striking is that with the reference to the hootch, the anonymous author uncharacteristically seems to take pains to imply that nobody saw what happened.

The first column (“The War Hero”) ran Tues., Oct. 24. Around that time, a fellow former Swift Boat commander, Edward (Tedd) Ladd, phoned The Globe’s Sennott to offer further details and was immediately passed on to me. Belodeau, a Massachusetts native who was living in Michigan, wanted to avoid further inquiries, I was told. I asked the campaign for an interview with Kerry. His staff promised one, but day after day, failed to deliver. Friday evening arrived and I was left with the draft of column for Sunday Oct. 27 about the citation’s unusual phrase (“Behind the Hootch”). It included a question that eventually came to be seen among friends as an inside joke aimed at other Vietnam vets (including a dear friend who sat five feet away in the newsroom): Had Kerry himself committed a war crime, at least under the terms of his own sweeping indictments of 1971, by dispatching a wounded man behind a structure where what happened couldn’t be seen?

The joke fell flat. War crime? A bad choice of words! The headline? Even worse. Due to the lack of the campaign’s promised response, the column was woolly and wholly devoid of significant new information. It certainly wasn’t the serious accusation that Kerry indignantly denied. Well before the Sunday paper appeared, Kerry’s staff apparently knew what it would say. They organized a Sunday press conference at the Boston Navy Yard, which was attended by various former crew members and the admiral who had presented his medal. There the candidate vigorously defended his conduct and attacked my coverage, especially the implicit wisecrack the second column contained. I didn’t learn about the rally until late that afternoon, when a Globe reporter called me for comment.

I was widely condemned. Fair enough: this was politics, after all, not beanbag. (Caught in the middle, Globe editor Storin played fair throughout with both the campaign and me). The election, less than three weeks away, had been refocused. Kerry won by a wider margin than he might have otherwise. (Kerry’s own version of the events of that week can be found on pp. 223-225 of his autobiography.)

• ••

Without knowing it, I had become, in effect, a charter member of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth. That was the name of a political organization that surfaced in May 2004 to criticize Kerry, in television advertisements, on the Web, and in a book, Unfit for Command. What I had discovered in 1996 was little more than what everyone learned in 2004 – that some of his fellow sailors disliked Kerry intensely. In conversations with many Swift Boat vets over the year or two after the columns, I learned that many bones of contention existed. But the book about the recent history of economics I was finishing and the online edition of EP that kept me in business were far more important. I was no longer a card-carrying member of a major news organization, so after leaving The Globe I gave the slowly developing Swift Boat story a good leaving alone. I spent the first half of 2004 at the American Academy in Berlin.

Whatever his venial sins, Kerry redeemed himself thoroughly, it seems to me, by declining to contest the result of the 2004 election, after the vote went against him by a narrow margin of 118,601 votes in Ohio. He served as secretary of state for four years in the Obama administration and was named special presidential envoy for climate change, a Cabinet-level position, by President Biden,

Baron organized The Globe’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Spotlight coverage of Catholic Church secrecy about sexual abuse by priests, and it turned into a world story and a Hollywood film. In 2013 he became editor of The Washington Post and steered a steady course as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos acquired the paper from the Graham family and Donald Trump won the presidency and then lost it. Baron retired in February. He is writing a book about those years.

But in 2003, John F. Kerry: The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best was published by PublicAffairs Books, a well-respected publishing house whose founder, Peter Osnos, had himself been a Vietnam correspondent for The Washington Post. Baron, The Globe’s editor, wrote in a preface, “We determined… that The Boston Globe should be the point of reference for anyone seeking to know John Kerry. No one should discover material about him that we hadn’t identified and vetted first.”

All three authors – Michael Kranish, Brian Mooney, Nina Easton – were skilled newspaper reporters. Their propensity to careful work appears on (nearly) every page. Mooney and Kranish I considered I knew well. But the latter, who was assigned to cover Kerry’s early years, his upbringing, and his combat in Vietnam, never spoke to me in the course of his reporting. The 1996 campaign episode in which I was involved is described in three paragraphs on page 322. The New Yorker profile by James Carroll that prompted my second column isn’t mentioned anywhere in the book; and where the Silver Star citation is quoted (page 104), the phrase that attracted my attention, “behind the hootch,” is replaced by an ellipsis. (An after-action report containing the phrase is quoted on page 102.)

Nor did Baron and I ever speak of the matter. What might he have known about it? He had been appointed night editor of The Times in 1997, last-minute assessor of news not yet fit to print; I don’t know whether he was already serving in that capacity in October 1996, when my Globe columns became part of the Senate election story. I do know he commissioned the project that became the Globe biography in December, 2001, a few weeks before terminating EP.

Kranish today is a national political investigative reporter for The Washington Post. Should I have asked him about his Globe reporting, which seems to me lacking in context? I think not. (I let him know this piece was coming; I hope that eventually we’ll talk privately someday.) But my subject here is how The Globe’s culture changed after NYT Co. acquired the paper, so I believe his incuriosity and that of his editor are facts that speak for themselves.

Baron’s claims of authority in his preface to The Complete Biography by the Boston Globe Reporters Who Know Him Best strike me as having been deliberately dishonest, a calculated attempt to forestall further scrutiny of Kerry’s time in Vietnam. In this Baron’s book failed. It is a far more careful and even-handed account than Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War (Morrow, 2004), historian Douglas Brinkley’s campaign biography. Mooney’s sections on Kerry’s years in Massachusetts politics are especially good. But as the sudden re-appearance of the Vietnam controversy in 2004 demonstrated, The Globe’s account left much on the table.

• ••

I mention these events now for two reasons. The first is that the Substack publishing platform has created a path that did not exist before to an audience – in this case several audiences – concerned with issues about which I have considerable expertise. The first EP readers were drawn from those who had followed the column in The Globe. Some have fallen away; others have joined. A reliable 300 or so annual Bulldog subscriptions have kept EP afloat.

Today, with a thousand online columns and two books behind me – Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton, 2006) and Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years (CreateSpace, 2018) – and a third book on the way, my reputation as an economic journalist is better-established.

The issues I discuss here today have to do with aspirations to disinterested reporting and open-mindedness in the newspapers I read, and, in some cases, the failure to achieve those lofty goals. I have felt deeply for 25 years about the particular matters described here; I was occasionally tempted to pipe up about them. Until now, the reward of regaining my former life as a newsman by re-entering the discussion never seemed worth the price I expected to pay.

But the success of Substack says to writers like me, “Put up or shut up.” After the challenge it posed dawned in December, I perked up, then hesitated for several months before deciding to leave my comfortable backwater for a lively and growing ecosystem. Newsletter publishing now has certain features in common with the market for national magazines that emerged in the U.S. in the second half of the 19th Century – a mezzanine tier of journalism in which authors compete for readers’ attention. In this case, subscribers participate directly in deciding what will become news.

The other reason has to do with arguments recently spelled out with clarity and subtlety by Jonathan Rauch in The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth (Brookings, 2021). Rauch gets the Swift Boat controversy mostly wrong, mixing up his own understanding of it with its interpretation by Donald Trump, but he is absolutely correct about the responsibility of the truth disciplines – science, law, history and journalism – to carefully sort out even the most complicated claims and counter-claims that endlessly strike sparks in the digital media.

Without the places where professionals like experts and editors and peer reviewers organize conversations and compare propositions and assess competence and provide accountability – everywhere from scientific journals to Wikipedia pages – there is no marketplace of ideas; there are only cults warring and splintering and individuals running around making noise.

EP exists mainly to cover economics. This edition has been an uncharacteristically long (re)introduction. My interest in these long-ago matters is strongly felt, but it is a distinctly secondary concern. I expect to return to these topics occasionally, on the order of once a month, until whatever I have left to say has been said: a matter of ten or twelve columns, I imagine, such as I might have written for the Taylor family’s Globe.

As a Stripes correspondent, I knew something about the American war in Vietnam in the late Sixties. As an experienced newspaperman who had been sidelined, I was alert to issues that developed as Kerry mounted his presidential campaign. And as an economic journalist, I became interested in policy-making during the first decade of the 21st Century, especially decisions leading up to the global financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath. Comments on the weekly bulldogs are disabled. Threads on the Substack site associated with each new column are for bulldog subscriber only. As best I can tell, that page has not begun working yet. I will pay close attention and play comments there by ear.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

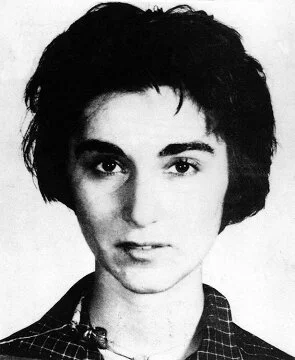

David Warsh: In the press, a dose of vicarious shock

“Kitty” Genovese

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a famous story from The New York Times in 1964.

37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police; Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector

by Martin Gansberg

For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law‐abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.

Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.

That was two weeks ago today. But Assistant Chief Inspector Frederick M. Lussen, in charge of the borough’s detectives and a veteran of 25 years of homicide investigations, is still shocked.

He can give a matter‐of‐fact recitation of many murders. But the Kew Gardens slaying baffles him — not because it is a murder, but because the “good people” failed to call the police.

The story of the killing of Catherine (“Kitty”) Genovese was widely read at the time and admired for decades. It made the reputation of A. M. Rosenthal, the metropolitan editor who caused it to be written and who argued its way onto the front page. Rosenthal’s own gloss on the story, “Thirty-Eight Witnesses,’’ was published within months. He rose rapidly at The Times, to be executive editor in 1977-1987, and for a dozen years after that, a columnist.

It turns out there was a backstory, too. In his book, Rosenthal disclosed how he himself had got the story, from Michael J. Murphy, theNew York City police commissioner, over lunch at Emil’s Restaurant and Bar on Park Row, near City Hall.

“Brother,” the commissioner said, “that Queens story is one for the books.”

Thirty-eight people, the commissioner said, had watched a woman being killed in the “Queens story,” and not one of them had called the police to save her life.

“Thirty-eight?” I asked.

And he said, “Yes, 38. I’ve been in this business a long time, but this beats everything.”

I experienced then that most familiar of newspapermen’s reaction — vicarious shock. This is a kind of professional detachment that is the essence of the trade — the realization that what you are seeing or hearing will startle a reader.

Some readers, including a television police reporter, Danny Meehan, doubted details of the story as soon as it appeared. Over the years various embellishments, inconsistencies, and inaccuracies came to light. In 2004 The Times took account of them. They did not change the essential fact at the heart of the story — a woman had been murdered in the middle of the night in a populous neighborhood, steps from her door. When her killer, Winston Moseley, died in prison, at 82, Robert McFadden summed up in a Times obituary:

The article grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived. None saw the attack in its entirety. Only a few had glimpsed parts of it, or recognized the cries for help. Many thought they had heard lovers or drunks quarreling. There were two attacks, not three. And afterward, two people did call the police. A 70-year-old woman ventured out and cradled the dying victim in her arms until they arrived. Ms. Genovese died on the way to a hospital.

I thought of the Genovese story because something of the sort happened in my neighborhood earlier this month — but in reverse. On Election Day, a 40-year-old woman was hit and killed in a crosswalk midday by a pickup truck.

Leah Zallman, 40, the mother of two young sons, was on her way home after voting at lunch time. She was the director of research at the Institute for Community Health, a primary-care physician at the East Cambridge Care Center, and an assistant professor of medicine at the Harvard Medical School

Talk about local apathy, at least in the public realm! Television stations reported the accident the day it happened. After that the news was only slowly shared, without details, first by the public school’s parent association, then on community Google groups. The city took a week to acknowledge on its Web site that it had happened. It was 10 days before The Boston Globe took account of it, and then only with a touching remembrance by a columnist free of any details of the accident itself, not even those that had been posted by the city:

An initial investigation suggests that the operator of the vehicle, an employee of the City of Somerville who was on duty at the time but operating their personal vehicle, had been attempting to take a left turn onto Kidder Avenue from College Avenue. They remained on the scene following the crash. Pending the results of an investigation [by the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office and Somerville Police], the employee has been placed on paid administrative leave…. No charges have been filed at this time.

We’ll learn more eventually from the Middlesex County investigation, including the identity of the driver, reported to be a Somerville building inspector, and the circumstances of his day. I wish that there were some local hero, a Rosenthal type, who could document how Zallman’s death could remain on the down-low for more than a week. (City councilors argued the details of the accident with the mayor and his Mobility Department behind the scenes.) Last year, when two women were hit after dark in a crosswalk, one of them killed, by a hit-and run driver less than mile away, it was big news. This time there were no flowers at the site, no other reminder of what happened at the busy crossing, no public outcry, no political outrage, only a lingering sense of shock.

It’s a commonplace that the invention of online search advertising has brought most metropolitan newspapers to their knees. In October the once-mighty Boston Globe reported print circulation of 84,000 daily and 123,000 Sunday, down from 530,000 and 810,000 respectively 20 years ago. The national papers have managed to hold their own so far. That small cities like Somerville, those of 100,000 people or so, haven’t found a way to rejuvenate the provision of local news bodes ill for their public life. With local journalism withering on the vine, we don’t have publicity, hence public outrage, over a traffic death that shouldn’t have happened. We don’t have accountability, either, sufficient to deter careless driving. Pickup trucks, in particular, often seem to confer a dangerous sense of privilege upon their drivers.

To be clear, I don’t think that what Abe Rosenthal did in 1964 was wrong, or wicked, in any sense, though in retrospect its self-aggrandizing subtext is hard to miss. Call it inflated-for-the-good-of-us-all journalism, the presentation of facts spiced with a special sauce of indignation for the purpose of making a point.

The Times had reported Genovese’s murder as an unvarnished matter of fact, when it occurred, in a short item buried deep inside the paper a couple of weeks before. To return to the story with additional facts — police commanders’ indignation – was in line with the performance of the newspaper’s duty to offer occasional moral instruction along with the news. But the embellishment went too far, and tarnished The Times’s most valuable asset, readers’ trust.

Newspapers have traditionally tried to rile up readers in a good cause in the three centuries they have been democracies’ dominant form of public communication. For a wry and affectionate look behind the scenes of inflated-for-the-good-of-us-all journalism at The Times in executive editor Rosenthal’s heyday, find a used copy of I Shouldn’t Be Telling You This, by Mary Breasted. Or rent a copy of Ron Howard’s brilliant 1994 film The Paper.

It seems the case that The Times has practiced more indignation-fueled news recently than usual – its 1619 Project, for example, provoked columnist Bret Stephens’s stinging dissent. The roots are the same as those Rosenthal identified in 1964: the experience of shock in the face of the facts. Rosenthal’s proud claim as editor was that “he kept the paper straight.” Think that is easy in times like these? Occasional large helpings of indignation are better than no news at all.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Now what after newspapers' colossal business mistakes?

Bridges, roads, airports, the electricity grid, pipelines, food and fuel and water systems: all of these are underfunded to some degree. So are the myriad new arrangements, from satellites and ocean buoys to emission scrubbers and ocean barriers, required to keep abreast and cope with climate change. Which wheels will begin to get the grease in coming months? We’ll see.

At the moment I am even more interested in the well-being of social information systems Last week The Wall Street Journal announced it would reduce its print edition from four sections to two on weekdays, bringing it into line with the Financial Times. Should that be an occasion for concern? On the contrary, let me try to convince you that it is welcome news.

Although newspapers still carry crossword puzzles, comics, agony aunts, and churn out all manner of fashion magazines, they are mainly in the business of producing provisionally reliable knowledge. What’s that? I have in mind propositions on which every honest and knowledgeable person can agree.

Not so much big judgment, such whether climate change is occurring or whether Vladimir Putin is a despot, but rather ascertainable facts, beginning with what parties to various debates are saying about themselves and each other and about their pasts. These are the foundations on which big judgments are based

A case in point: almost all of what the world knows about Donald Trump, that is, that we consider that we really know, we owe to The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, the Financial Times, and various newspaper-like organizations, Bloomberg News, Politico, and The Guardian in particular. The Associated Press, Reuters and the BBC contributed a little less; magazines still less; the rest of radio and television, hardly anything at all, with the notable exception of Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly’s lead off question in the first presidential debate. Someone will prepare a list of the fifty or a hundred of the best stories of the last year, I expect. I’ll only mention a few memorable examples:

The Post’s coverage of the Trump Foundation; the Times’ many investigations, including those of his tax strategies and his practices as a young landlord; a Politico roundtable of five Trump biographers; the WSJ’s pursuit of the George Washington bridge closing, coverage that changed the course of the campaign; and the FT’s continuing emphasis on the foreign policy implications of the America election. The same thing could be said about newspapers’ coverage of Hillary Clinton.

Newspapers exist to process and assess the rival claims of experts – politicians, governments, corporations, the professoriate, pollsters, authors, whistleblowers, filmmakers, and denizens of the blogosphere. When its own claims to authority are misplaced – a spectacular example having been the Monday before the election, when newspapers were still expecting a Clinton victory – the print press and its kith and kin correct themselves (the next day) and investigate the prior beliefs that led them to error. A free and competitive press resembles the other great self-correcting systems that have evolved over centuries – democracy, markets, and science.

And as for social media, the new highly decentralized content producers, to the extent they are originators of new information, the claims made there are slowly becoming subject to the same checking and assessment routines as are claims advanced in other realms. (No, the Pope did not endorse Donald Trump.) As for intelligence services, in which the experts’ job is to know more than is public, it is the newspapers that make them less secret. More than any other institution in democratic industrial societies, newspapers produce a provisional version of the truth. So the condition of newspapers should concern us all.

In “What If the Newspaper Industry Made a Colossal Mistake?,’’ in Politico, Jack Shafer speculated recently the newspaper companies had “wasted hundreds of millions of dollars” by building out Web operations instead of investing in their print editions, “where the vast majority of their readers still reside and where the overwhelming majority of advertising and subscription revenue still come from.” As perspicacious a press critic as is writing today, Shafer was reporting on an essay by a pair of University of Texas professors, H. Iris Chyi and Ori Tenenboim, in Journalism Practice.

Chyi and Tenenboim overstated their case, I think. Those dollars invested in Web operations weren’t wasted; they had to be spent. Most newspapers, all but the WSJ, made the mistake of making their content free on the Web for several years. Only gradually did they come round to the approach the Journal had pioneered: a paywall, with some sort of a metering technology designed to encourage online subscriptions.

More serious has been the lack of thinking-out-loud about the future of those print editions. No one needs to be told that smart phones have replaced newspapers, radio, and television as the tip of the spear of news. It appears that Facebook and Twitter have supplanted cable television and radio talk shows as the dominant forum for political discussion. But newspapers haven’t gone away; indeed, by establishing beachheads for the content they produce on social media platforms, they have become more influential than ever.

The immense prestige associated with newspapers arose from the fact that for centuries they were reliable money machines, thanks to their semi-monopoly on readers’ attention. It is no longer news that the revenue model has turned upside down, Advertisers used to pay two thirds or more of the cost of publishing a successful newspaper; today it is more like a third, if that. Attention was slowly eroded away by radio, broadcast and pay television, until the invention of search-based advertising in 2002 turned decline into a seeming rout. The basic business model is still the same, as Tim Wu explains in The Attention Merchants; The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads (Knopf, 2016): “free diversion in exchange for a moment of your consideration, sold in turn to the highest-bidding advertiser.” It’s the technology that has changed.

In a world in which the gas pump starts talking to you when you pick up the hose and video commercials are everywhere online, the virtues of print are many-sided, for readers and advertisers alike. In “Why Print Still Rules,’’ Shafer laid out the case for print’s superiority as a medium – “an amazingly sophisticated technology for showing you what’s important, and showing you a lot of it.” It’s finite. It attracts a paying crowd, which is why advertisers are willing to pay more – much more – for space.

The fancy newspapers are in good shape to refurbish their printed editions. Three of the four have new owners with deep pockets. Rupert Murdoch, a maverick Australian, now a U.S. citizen, bought the WSJ in 2007; Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, thought to be the second richest American, after Bill Gates, bought the Post, in 2013; the Japanese newspaper group around Nikkei bought the FT in 2015. The NYT is the shakiest of the four, but there seems little doubt that the cousins of the Sulzberger/Ochs clan will find a suitable partner, the oft-expressed enmity of President-elect Trump notwithstanding.Fav

Pricing, meanwhile, is all over the map, as is the appropriate size of the paper edition itself. The FT delivers two sections of tightly written no-jump news over five days and a great weekend edition for $406 a year. The WSJ costs $525 a year for six days, including a first-rate weekend edition. The Times charges $980 a year for seven days a week, including a Sunday edition that contains much more content than most readers need. (Its ads bring in a ton of money.) That’s why the WSJ decision to cut back to from four to two daily sections is significant: it acknowledges the reduced but still very powerful claim of print on consumers’ ever-more stretched budget of time. It puts more pressure on the Times’s luxury brand.

It’s the regional papers that worry me, as much for their roles as distributors of news as producers of it. When the Times, WSJ and FT are placed on the stoop in the morning, my old paper, The Boston Globe, is not among them. At around $770 a year, it simply costs too much, especially considering the meager local content it provides.

Assume that the “right” price for a year of a fancy paper today is somewhere between the FT and the WSJ, at around $500 a year. At around half as much, or even $300, a print edition of the Globe would be highly attractive. My hunch is that circulation would again begin to increase, and, in the process, shore up the metropolitan area’s home-delivery network. Instead I buy digital versions of the Globe (for $208) and the Post (for $149). Want to know what a year of the print Post costs? So does the copy editor. But I stopped looking after interrogating the Web page for five minutes. Newspapers are notorious for gulling their subscribers. Not even the FT is straightforward about it.

Like the other leading papers – the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, and Baltimore Sun – the Globe was sold for a song to a non-newspaper owner in the course of the panic that followed the advent of search advertising in 2002.

These publishers no longer seem to see themselves as part of an industry that was quite tight-knit before the fall. That’s another disadvantage with which the big national dailies must cope. For many years, newspaperfolk considered that their businesses were mostly exempt from the laws of supply and demand. Price cuts play a big part in the lore of its past. Today, the future of the industry depends on the recognition that price/performance is everything.

. xxx

Around two years ago, I began to think it was fairly likely that a Republican would win the election in 2016. So I am not altogether surprised that this has turned out to be the case. I am, however, astonished that it is Donald Trump who has been selected to provide the zig to President Obama’s zag. The Republicans found their crossover voters elsewhere.

Trump breaks promises as easily as he makes them. Look past his odious qualities (not easy to do) and you’ll see that among the policies he seems likely to embrace are several that GOP conservatives have refused to permit the Democrats to carry out. Trump apparently favors a big jobs bill, a $1 trillion stimulus; let’s see what the Tea Party-goers say now about the national debt. He is a realist in foreign relations, likely to stop baiting Russia with NATO enlargement and the threat of intervention in Syria. At least in his personal views, he has been a social liberal. His position will probably swing round even on climate change, as the trends continue to become more clear. The Supreme Court? He could challenge his uneasy Republican allies in Congress by re-nominating Judge Merrick Garland if he were interested in governing instead of showing off.

Trump has reinvented himself several times before. Now that he is president-elect, he will try to do it again. This time I very much doubt that he will be successful. Nothing in his background prepared this dubious projector for the presidency. This time Trump won’t escape his past.

David Warsh, a longtime financial columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this originated.

David Warsh: Globe arts revival and my migration