David Warsh: Of sportswriters, race and great news publications

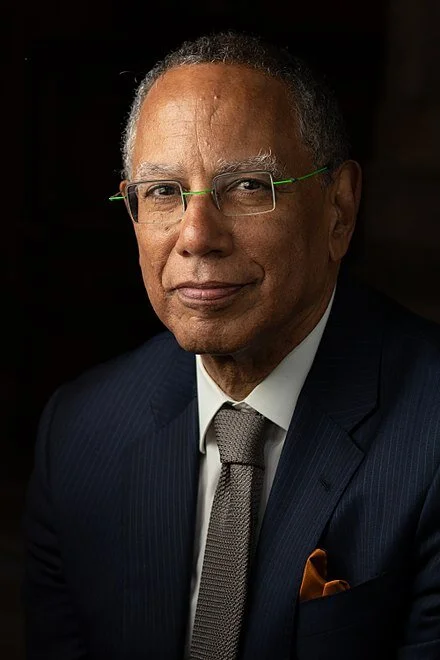

New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Because it was August, I was reading Tall Men, Short Shorts, the 1969 NBA Finals: Wilt. Russ. Lakers. Celts, and a Very Young Sports Reporter (Doubleday, 2021). Leigh Montville was one of the many excellent sports columnists at The Boston Globe in the twenty years that I was there, somebody whom I always read no matter who or what he was writing about. After he was unreasonably refused an exit as columnist from the ghetto of sports, he left the paper for Sports Illustrated, where he wrote extended features and the back-of-the-magazine column for many years. He wrote eight books along the way. Tall Men, Short Pants is his ninth, a summing-up of much he learned about life in a fifty-year career as a journalist.

I’d been alerted to the book by The Globe’s former long-time managing editor, Thomas F. Mulvoy, who wrote about it in the Dorchester Reporter. At one point, Mulvoy says:

In a section that comes off the page with a sharp edge of sadness, Montville redresses himself (for the umpteenth time, his words suggest) for his silence at the press table when the Celtics played the Knicks in New York earlier in the season. A Globe colleague sitting next to him gave vent to his bigotry by loudly and repeatedly using the N-word while talking about the game being played in front of them. [Montville] writes: “I have thought for all these years of the things I should have done. I should have told [him] to shut up. Right away, I should have done that. If he didn’t shut up, I should have grabbed him, done something. … I should have reported all this to someone at the Globe on our return. I should have decided never to talk to him again. I should have done any of this stuff. I did nothing”

The 26-year-old Montville, who is White, served as no more than witness that day – the book reveals how he learned that his Globe colleague was deliberately baiting another Globe sportswriter, a well-known liberal, nearby – only much later affording a glimpse of the fractious mood of the nation in 1969. Montville attended his colleague’s wake thirty years later. Otherwise, he imaginatively covered changing attitudes about race in America, in columns and books, including Manute: The Center of Two Worlds (2011), and Sting like a Bee. Muhammad Ali vs. the United States of America, 1966-1971 (2017). Sports has done more than its share, and better than Hollywood, to illuminate rapidly changing stereotypes of race and class in the last fifty years. Montville was alert to the story every step of the way.

Reading Tall Men, Short Pants brought into focus a project of The New York Times of which I gradually became aware over the last couple of years.

I do not mean the paper’s scrutiny of the killings of Black men and the occasional Black woman by Whites, mostly police officers, before George Floyd was murdered by Officer Derek Chauvin, in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, though even now, thanks to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, it seems important to remember their names.

(Those whose stories made the front pages include Trayvon Martin, in Sanford, Fla; Eric Garner, in Staten Island, New York; Michael Brown, in Ferguson, Mo.; Walter Scott, in North Charleston, S.C.; Philando Castile, in St. Paul; Stephen Clark, in Sacramento, and Breonna Taylor, in Louisville.

Nor do I mean the special issue of the magazine called The 1619 Project, the Times’s coverage of the debate over Critical Race Theory, or the series of essays by critic-at-large Wesley Morris that earlier this year was recognized with a Pulitzer Prize. I have in mind something less concrete but ultimately even more eye-opening, at least to me.

I am thinking of a surge of ordinary news stories about contributions to American culture by African-American citizens. These stories appeared in unusual numbers, day after day, over the course of the last eighteen months. In the trade, this kind of display is called ROP, or run of the paper, with stories placed anywhere in the paper at the option of an editor – world, U.S., politics, NY, business, opinion, tech, science, health, sports, arts, books, style, food, travel, real estate, obituaries. The surge was as unmistakable as it is difficult to describe. Instead of data, I have only personal experience of it, to which I aim to testify here, briefly.

I scan the print editions of The Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each morning at home, glance online at Bloomberg and study the story list of The Washington Post when I reach the office. In the evening, I read and clip (or print) whatever is most important to me. The differing trajectories of these five great English-language news organizations in the thirty years since the Internet emerged as a public communications medium has been fascinating, but that is a subject for another day. For now it is enough to say that The Times remains the most ambitious among them, more sparkling than ever in its aspirations.

It was the morning scanning of The Times that first produced the effect. So relentless had its coverage of Blacks newsmakers and their concerns become over the last year that one day it dawned on me what The Times had achieved. Some of the stories made big impressions. Others seemed peripheral, at least to my interests. I discussed the experience with my friend, Vincent McGee, who described it thus: “I first noticed it with obituaries, some current – mainly arts, music and sports – and others ‘catch ups’, often of Black women lost in history.”

By distorting its usual budget of stories – not much, mind you, this was only a surge – the newspaper’s editors had given me, a White reader, the feeling of somehow being unimportant. For some fleeting part of the day, I felt as many Black readers must feel most days, oppressed by the relentless attention The Times paid to the Other. This was showing, not telling, how it felt to be left out. It showed, too, what it meant to be included in. As an exercise in good newspaper editing, I will never forget it.

How had the decision to reorient the coverage been made? Anyone who knows anything about newspapers understands that inspiration comes from the bottom up. Orders are given, of course; stories are assigned, or turned back for more work. There are countless meetings, discussions, bull sessions, retreats. Word gets around. Better to say that a curiosity about race, gender, ethnicity and discrimination had been authorized at The Times as long ago as the Nineties, then encouraged, becoming wide-ranging, before coming to a low boil in 2020.

The Times’s executive editor is Dean Baquet, who was born in 1956. He is a consummate newspaperman, having started working in New Orleans even before graduating from Columbia University, in 1978. He moved from The Times-Picayune, in New Orleans, to the Chicago Tribune in 1984, where he won one Pulitzer Prize, and just missed another, before joining TheTimes, in 1990. Tribune Co. hired him back in 2000 to serve as managing editor of its newly acquired Los Angeles Times; he replaced John Carroll as editor in 2006 but was quickly dismissed after opposing newsroom budget cuts. He returned to The Times later that year as its Washington bureau chief, became its managing editor in 2011, and succeeded Jill Abramson in the top newsroom job in 2014.

Baquet is also a Black man, the fourth of five sons of a successful New Orleans restaurateur. Many years will be required to hash out all that has happened on his watch, some of it under the heading of “woke.” Baquet will write a book. Culture wars will continue. The equitable distribution of attention – of “play” – will become the next editor’s problem. Baquet turns 65 later this month; he will retire next year.

Leigh Montville won the Associated Press Sports Editors Red Smith Award in 2015; he never got out of the sportswriting ghetto, but he nevertheless became one of the finest columnists of his generation, pure and simple. Dean Baquet broke race out of the newspaper ghetto and made it ROP, maintaining news values evolved by the modern profession. He will enter history books as one of The New York Times’s greatest editors. Both men made the most of their opportunities.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.