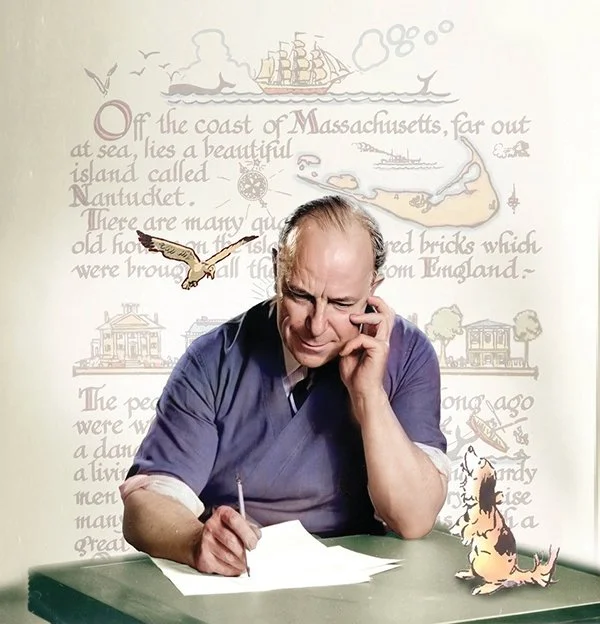

A kind of genius

From the show “Tony Sarg: Genius at Play,” now at the Nantucket Historical Association/Whaling Museum.

Edited from the gallery’s statement:

This is is “the first comprehensive exhibition exploring the life, art, and adventures of Tony Sarg (1880–1942). Known as the father of modern puppetry in North America and the originator of the iconic Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade balloons, Sarg was a famed illustrator, animator, designer and nimble entrepreneur who summered on, and took inspiration from, Nantucket for nearly 20 years. Organized and in partnership with the Normal Rockwell Museum, in Stockbridge, Mass.’’

Nantucket from a NASA satellite

Using fungi instead of petroleum

A series of fungi.

— Collage by BorgQueen

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Anything we can do to get off many manmade toxic chemicals the better, in small and large places. Researchers and business have been stepping up efforts to get off problematical chemicals by turning to natural solutions.

Boston’s WBUR reports that one quirky example is on Nantucket, which is experimenting with “MycoBuoys,” made from the root-like part of mushrooms (which, of course, are fungi), to replace petroleum-based Styrofoam buoys used in scallop, oyster, and mussel aquaculture to hold up spat collectors. The Styrofoam degrades, releasing microplastics that pose health risks to animal life in general. In this case, they may have been harming shellfish reproduction.

When shellfish reproduce, they spawn tiny larvae that move in the water until they find a structure to settle on. Once the larvae permanently attach to a surface, they are known as spat and, hopefully, grow to harvestable-sized shellfish.

The hope is that the buoys will last five to eight months. Town officials will see if their use can increase the number of scallops. If so, that could be an economic boon. Scallops sell for a pretty price.

Fungi can be used in a wide variety of ways to reduce the use of manmade chemicals. These include medicine, fuel, fertilizers, cosmetics, clothing and footwear. And reducing the production of manmade chemicals reduces the burning of fossil fuels.

Where will the coastal year-rounders live?

Stonington waterfront in1915

Aerial view of fancy summer resort town Camden, Maine, from the harbor

—Photo by King of Hearts

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘Many coastal communities in New England face severe housing shortages for year-round residents of modest means. Around here, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Block Island are infamous for this problem.

Consider Stonington, Maine, on Deer Isle. There, 80 percent of its shorefront is now owned by non-residents (mostly summer people), as are 56 percent of that fishing (mostly lobsters) port’s downtown properties, according to a report in the Portland Press Herald

The usually affluent summer folks bid up real estate prices to levels unaffordable to most year-rounders.

So where will the carpenters, yard-work people, plumbers, electricians and schoolteachers live? Perhaps some elderly summer people will leave their summer McMansions to towns to be converted into affordable housing. Just joking. But something must be done if these towns are going to have enough of the locals who make communities viable for year-round and summer people. That includes zoning changes and/or having states subsidize the construction of new housing in some places.

Lunar exploration

“A Different Dawn” (encaustic) by Boston-based painter Deniz Ozan George, in her show “Wax and Wane…Ebb and Flow,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, July 1-31.

She says:

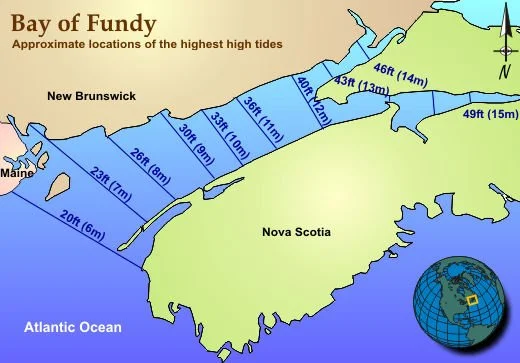

"‘Wax and Wane... Ebb and Flow’ is a personal exploration of the magical and enduring presence of the moon through its many phases, its pull on the oceans' tides and its effect on the life cycles of all living things.

“These mysteries are expressed through the medium of encaustic wax painting and Japanese nihonga-inspired mineral pigment distemper painting.’’

The Bay of Fundy has the highest tides in the world.

The Maria Mitchell Observatory on Nantucket was founded in 1908 and named in honor of Maria Mitchell, the first American woman astronomer. The observatory consists of two observatories - the main Maria Mitchell Observatory near downtown Nantucket and the Loines Observatory (in photo), west of downtown.

‘From sea’s slime’

The town on Nantucket Island, when it was still called Sherburne, in 1775.

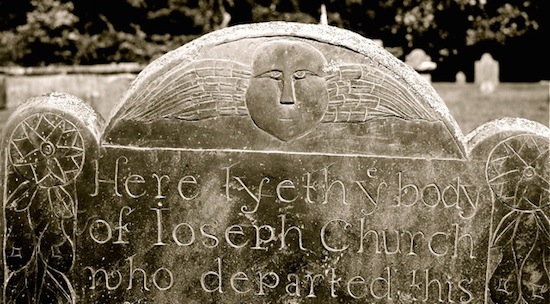

“Here in Nantucket, and cast up the time

When the Lord God formed man from the sea's slime

And breathed into his face the breath of life,

And blue-lung'd combers lumbered to the kill.’’

— From “The Quaker Graveyard at Nantucket,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)

What can be endured?

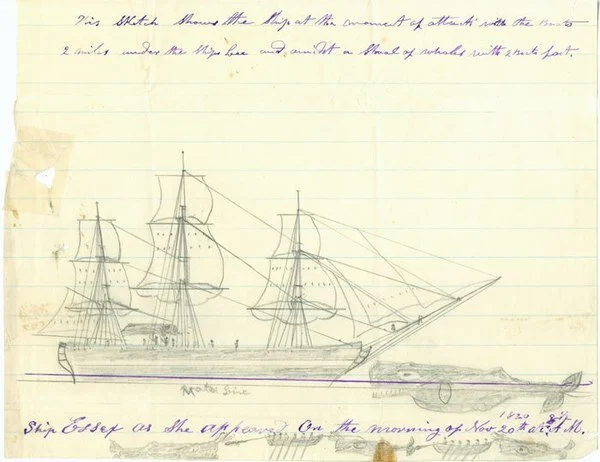

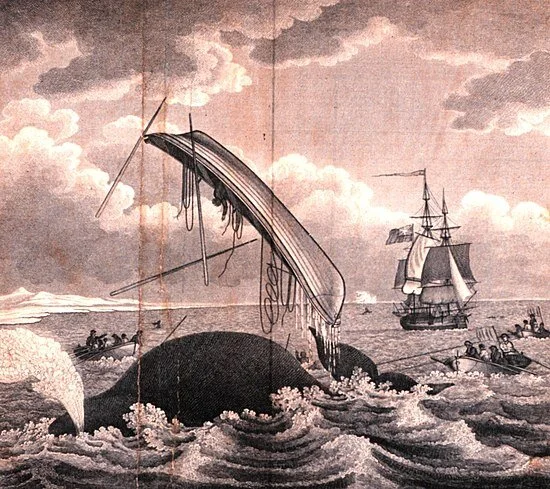

Sperm whale striking The Essex on Nov. 20, 1820 (sketched by Thomas Nickerson)

“There is no knowing what a stretch of pain and misery the human mind is capable of contemplating when it is wrought upon by the anxieties of preservation; nor what pangs and weaknesses the body is able to endure, until they are visited upon it; and when at last deliverance comes, when the dream of hope is realized, unspeakable gratitude takes possession of the soul, and tears of joy choke the utterance.’’

-- Owen Chase, sailor, in Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex, of Nantucket

Here’s an edited version of a good Wikipedia summary of the background of this horror story:

“The Essex was a whaler from Nantucket launched in 1799. In 1820, while in the Pacific Ocean under the command of Capt. George Pollard Jr., she was attacked and sunk by a sperm whale. Thousands of miles from the coast of South America with little food and water, the 20-man crew was forced to try to make for land in the ship's surviving whaleboats.

“The men suffered severe dehydration, starvation, and exposure on the open ocean, and the survivors eventually resorted to eating the bodies of the crewmen who had died. When that proved insufficient, members of the crew drew lots to determine whom they would sacrifice so that the others could live. A total of seven crew members were cannibalized before the last of the eight survivors were rescued, more than three months after the sinking of The Essex. First mate Owen Chase and cabin boy Thomas Nickerson later wrote accounts of the ordeal. The tragedy attracted international attention, and inspired Herman Melville to write his 1851 novel Moby-Dick.’’

Thomas A. Barnico: Should Feds dictate rules on campus sexual misconduct? Beware

“My Eyes Clear Away Clouds” (collage), by Timothy Harney, a professor at the Montserrat College of Art, in Beverly, Mass.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Department of Education is poised to reverse Trump-era rules governing claims of sexual misconduct on campus. One could forgive weary college counsel for a case of vertigo: The Trump rules themselves reversed the Obama rules, and Biden’s 2021 nominee to enforce the rules—Catherine Lhamon—held the same office at the Education Department under Obama. In three years, the election of 2024 may bring yet another volte-face at the department. Even those who support the likely Biden changes may wonder: Is this any way to run a government?

As they ponder that question, frustrated counsel should note the primary source of the problem: the desire by serial federal officials to dictate hotly contested standards of student conduct for millions of students in thousands of colleges in a nation of 330 million people.

Some issues are better left to the provincials. As Duke Law professors Margaret Lemos and Ernest Young argue: “Federalism can mitigate the effects of [national] political polarization by offering alternative policymaking venues in which the hope of consensus politics is more plausible.” Delegation to state or local governments or, in education, to private actors, can “operate as an important safety valve in polarized times, lowering the temperature on contentious national policy debates.”

Of course, as Lemos and Young admit, “a federalism-based modus vivendi is unlikely to satisfy devoted partisans on one side or another of any divisive issue.” Such conflicts pit competing and compelling interests against one another.

In the Title IX context, parties fiercely debate the adequacy of protections for complainants and respondents alike: Does the respondent have a right to confront and cross-examine the complainant? Does the respondent have a right to counsel in their meeting with student affairs personnel? Do colleges and universities have to abide by a common definition of “consent” to intimacy in their student conduct manuals?

And, in polarized times, many will be unsatisfied with a patchwork of rules that apply state-by-state or college-by-college. Lost in this good-faith debate is the point that, even for issues with national effects, an oscillating national rule can cause more instability than an entrenched array of differing local rules.

Noted diplomat and scholar George F. Kennan aptly described the problem in Round the Cragged Hill: “The greater a country is, and the more it attempts to solve great social problems from the center by sweeping legislative and judicial norms, the greater the number of inevitable harshnesses and injustices, and the less the intimacy between the rulers and ruled. … The tendency, in great countries, is to take recourse to sweeping solutions, applying across the board to all elements of the population.” Central dictates, Kennan said, often show “diminished sensitivity of … laws and regulations to the particular needs, traditional, ethnic, cultural, linguistic and the like, of individual localities and communities.”

Of course, changes in administrations often bring changes in policy. Elections matter, and victors arrive with fresh ideas and an appetite for change. This is a highly democratic impulse; as U.S. Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote: “A change in administration brought about by the people casting their votes is a perfectly reasonable basis for an executive agency’s reappraisal of the costs and benefits of it programs and regulations.”

Sometimes, such reappraisals will follow a reversal in the public current of the times. Where the new current runs strong and fast—and newly elected officials carry a decisive electoral mandate—a sweeping national solution may reflect a consensus view. But when electoral margins are slim, dangers lurk. When national executive and legislative power repeatedly changes hands by slim margins, policy changes may reflect not strong new currents but more of a series of quick, jolting bends.

The shifting procedural rights of the complainants and respondents in the Title IX misconduct hearings more resemble the latter. The abruptness of such changes grows when the commands flow not from a congressional act but by “executive order,” administrative “guidance,” or “Dear Colleague” letters that lack the procedural protections of a statute passed by both houses of Congress. Moreover, too-frequent changes in rules—whatever their procedural sources—have long been seen to create uncertainty, undermine compliance and lessen respect for law.

The options for beleaguered college counsel are few. Education Department rules apply to colleges because colleges desire federal funds. Few colleges wish to turn off the spout of the federal Leviathan. The masters they acquire are both the sovereign Leviathan of Hobbes and the whale dreamed by Herman Melville in Moby-Dick: a giant of the deep that pulls colleges to and fro, as if dragging them in a whaleboat on a “Nantucket Sleigh Ride.”

In our modern form of the tale, the whaleboat is the college, and the harpoon is its application for federal funding. The harpoon hits its rich federal target, but the prize brings conditions, represented by the attached rope. “Hemp only can kill me,” Ahab prophesizes. “The harpoon was darted; the stricken whale flew forward; with igniting velocity the line ran through the groove;—ran foul.” The rope—initially coiled neatly in a corner of the whaleboat—runs out smoothly until spent. Then it tangles, converting itself to a weapon more deadly than the harpoon. Bound by the rope—the conditions on federal funding—the college descends into the vortex.

Biden’s likely Title IX rules on student misconduct will pull college administrators to and fro again, whalers on a new, hard ride. The day that the federal government withdraws from the field seems distant; like Ahab, Education Department officials of both parties seem “on rails.” In the meantime, college counsel should brace for the latest chase and hope that they—like Ishmael—will live to tell the tale.

Thomas A. Barnico teaches at Boston College Law School. He is a former Massachusetts assistant attorney general (1981-2010).

“Nantucket Sleigh Ride”: Illustration of the dangers of the "whale fishery" in 1820. Note the taut ropes on the right, lines leading from the open boats to the harpooned animal.

Keep your virus off our island!

On Matinicus, 20 miles off Maine’s mainland

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The reaction of residents of islands off the New England coast, from big ones, such as Nantucket, to tiny Matinicus, off Maine, to the pandemic has, in a way, been paradoxical. These folks (more than a few of whom tend to be recluses) sometimes feel safer because they are separated by water from the worst COVID case densities, on the mainland, while fearful that a few cases will make their way onto their islands and explode.

There have been some ugly scenes, such as locals stretching chains across driveways of summer people “From Away’’ trying to shelter in place from COVID there and nasty notes.

xxx

Of course, New England’s islands are a big lure in the summer. I wonder how the vaccination surge will affect how many tourists and vacation-home residents visit them this summer as they play travel catch-up.

Is Watch Hill in Rhode Island?

Watch Hill Harbor

A colleague in a business ZOOM meeting I was in last Friday suggested that Rhode Island Gov. and former venture capitalist Gina Raimondo will not return to Rhode Island after she serves as Joe Biden’s commerce secretary. — that she’ll join the swells and move to some fancy out-of-state place.

No, I suggested, only half-jokingly, she’ll move to hyper-rich Watch Hill. Then another colleague quipped: “Is that in Rhode Island?” I had had a sleepless night and so too quickly and stupidly answered what everyone in the meeting well knew: “Watch Hill is in Rhode Island; it’s part of Westerly.’’

But in a psycho-sociological way, it’s not in Rhode Island. Like some other fancy places in New England — say Nantucket, Mass., and Northeast Harbor, Maine, it transcends its state; above all, it’s part of the Federated Principalities of the Plutocracy.

— Robert Whitcomb

Yachts in Nantucket

In Northeast Harbor. See mansions on the hillside.

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

Breakthrough on Nantucket

Post office in the Nantucket village of Siasconset, on the eastern end of the town/island. Nicknamed “Sconset,’’ it’s where Alice Killer spent a few cold-weather months in 1962-63 as she sought to better understand herself and change her life.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Philosopher, with a PhD, and writer (mostly as a kind of memoirist) Alice Koller, who died July 21 at 94, was the author of two books that continue to have a following. These are An Unknown Woman and The Stations of Solitude. Parts of them recall, slightly, Thoreau’s Walden.

Ms. Koller may have often been an impossible person to be around for long. And so her painfully reached decision, in lieu of the suicide she considered, to hereafter live, but alone, and stop wasting time and energy trying to meet her own outdated or false expectations, and those of others, was good for all concerned. She came to the decision in winter of 1962-63 while living alone, except for her German Shepherd puppy, on the easternmost shore of Nantucket, an experience that’s the core of An Unknown Woman. That dog, Logos, and her two other dogs that followed played key roles in her life, becoming her family.

Her rigorous self-analysis as she explored the sources of her misery has lessons for everybody seeking to live with more integrity, independence and creativity, though few will want to emulate her life, which had much poverty and other challenges, some caused by things out of her control and some by her own eccentricity and willfulness. Oddly, her self-involvement doesn’t come across as narcissism but rather as honest, hard-working attempts, informed by curiosity, to come to terms with the reality of her past and present.

Ms. Koller was also a fine writer about nature – the landscapes, creatures and weather -- in the various places she lived, from the moors and beaches of Nantucket to the woodsy exurban towns where she mostly lived afterwards.

One of “Sconset’s’’ old cottages. At least one of them dates back to the late 17th Century.

A Nantucket origin story

Nantucket from a satellite. Martha’s Vineyard’s Chappaquiddick Island is on the left.

“Look now at the wondrous traditional story of how this island {Nantucket} was settled by the red-men. Thus goes the legend. In olden times an eagle swooped down upon the New England coast, and carried off an infant Indian in his talons. With loud lament the parents saw their child borne out of sight over the wide waters. They resolved to follow in the same direction. Setting out in their canoes, after a perilous passage they discovered the island, and there they found an empty ivory casket --the poor little Indian's skeleton.’’

-- From Moby-Dick (1851), by Herman Melville (1819-91)

Todd McLeish: Finding rare species in Marine Monument off N.E.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A team of scientists from the New England Aquarium, in Boston, has been conducting periodic aerial surveys of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument, some 130 miles off Nantucket, and has documented an impressive list of marine mammals and fish that illustrates why conservation organizations have been advocating for its protection for years.

A late-October survey, for instance, documented three species of rare beaked whales, three kinds of baleen whales, four species of dolphins, several ocean sunfish — the largest bony fish in the world — and two very unusual Chilean devil rays

“We’re out there documenting what’s out there to show that the area is important and should continue to be protected,” said Ester Quintana, the chief scientist of the aerial survey team. “Every survey is different, and you never know what you’re going to see, so it’s always exciting.”

The beaked whales were particularly notable, since they are rare and difficult to observe. Beaked whales are deep-diving species that can remain under water for more than an hour and only surface briefly to breathe.

“If you’re not at the location where they come to the surface, then you’re not going to see them,” Quintana said. “There are probably more of them out there that we were just not seeing.”

The survey team observed two Cuvier’s beaked whales, three Sowersby’s beaked whales, and four True’s beaked whales, the latter of which hadn’t previously been documented in the 4,900-square-mile monument during an aerial survey, though a ship-based group of researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration had seen several there last year.=

Also observed were large numbers of Risso’s dolphins, plus groups of bottlenose dolphins, common dolphins and striped dolphins, along with nine fin whales, two sperm whales, and one humpback.

“We didn’t see many individual whales, but that’s just the difference between an October survey and the surveys we’ve done in the summer,” Quintana said.

Of special note were the two Chilean devil rays observed, the first time Quintana had ever seen the species.

“Last year we saw a big manta ray, which was a surprising sighting because we were unaware that they could be sighted this far north,” she said. “So when we saw the Chilean devil ray at the site, it was another unexpected ray. They’re not that uncommon, but in the seven surveys we’ve conducted, it was the first we saw at the monument.”

About the size of Connecticut, the only Atlantic Ocean marine monument includes two distinct areas, one that covers three canyons and one that covers four seamounts. (NOAA).

Chilean devil rays can swim about a mile deep, and since they don't have to come to the surface to breathe, it’s unusual to see them.

The survey team flies transect lines back and forth over the three underwater canyons in the monument — Oceanographer Canyon, Gilbert Canyon and Lydonia Canyon — with most of the wildlife observed at Gilbert and Lydonia canyons. As soon as team members observe wildlife to document, they depart from their transect and circle the animal to identify and photograph it. The plane is equipped with a belly camera that takes photographs every 5 seconds during the survey in case the two observers miss anything.

Quintana said the team was unable to survey the waters around the monument’s four seamounts (underwater mountains), because those sites are farther away and their small plane can’t carry enough fuel to reach them.

The wide variety of marine life observed during the survey are attracted to the monument because of its diversity of habitats.

At a lecture last February describing the monument, Peter Auster, senior research scientist at Mystic Aquarium, in Mystic, Conn., said: “Those canyons and seamounts create varied ecotones in the deep ocean with wide depth ranges, a range of sediment types, steep gradients, complex topography, and currents that produce upwelling, which creates unique feeding opportunities for animals feeding in the water column.”

The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument was designated by President Obama in September 2016. It’s the only marine national monument in the Atlantic Ocean. Early in President Trump’s administration, he threatened to revoke the site’s designation, despite uncertainties as to whether he could legally do so. Those threats triggered efforts by conservation groups to document the value of the site to wildlife.

The next aerial survey by the New England Aquarium team will take place as soon as the weather cooperates. Conditions must be calm to allow for a safe flight and smooth seas so conditions are optimal for observing marine life.

“We’ve never done a survey in the winter because it’s hard to plan one because of the weather,” Quintana said. “No one has ever done a survey there in the winter, so we don’t know what to expect once we get there.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

A beaked whale

CEO imperialism on Nantucket

Theodore Robinson's painting Nantucket, (1882) -- way before the modern fat cats arrived to take over much of the island.

From Robert Whitcomb's Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

A rich Nantucket summer resident (and that’s sort of a redundancy these days) is fighting mightily to prevent the Nantucket Land Bank from building a small dormitory for 22 seasonal workers to address in a minor way the deep affordable-housing crisis on that billionaire-dense island, where some workers have had to sleep on floors or in vehicles and shipping containers. The dorm would be 350 feet, but well shielded by trees, from the 5,700-square-foot wooden chateau of David Long, the CEO of Liberty Mutual, the Boston-based insurance company. He calls the place “Summer Wind.’’

Long has hired a bunch of high-priced lawyers to try to kill the project through assorted technical arguments even as the Board of Selectmen and most others on the island support it. Long doesn’t want the peasantry near him.

Long may be typical of the imperial executives who have been running companies (and now the United States) since the ‘80s – obsessed with maximizing their personal wealth above all else and wallowing in conspicuous consumption. They tend to have houses in places such as the Hamptons and Nantucket which, since crowded by other rich people, further inflates their self-importance.

Long was paid about $20 million last year, and, as The Boston Globe famously noted, $4.5 million was spent to renovate his 1,335-square-foot office (throne room?) at Liberty Mutual.

Such folks are making Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard boring. They’re building a Greenwich, Conn., on sand dunes.

CEO imperialism on Nantucket

Theodore Robinson's painting Nantucket, (1882) -- way before the modern fat cats arrived to take over much of the island.

From Robert Whitcomb's Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

A rich Nantucket summer resident (and that’s sort of a redundancy these days) is fighting mightily to prevent the Nantucket Land Bank from building a small dormitory for 22 seasonal workers to address in a minor way the deep affordable-housing crisis on that billionaire-dense island, where some workers have had to sleep on floors or in vehicles and shipping containers. The dorm would be 350 feet, but well shielded by trees, from the 5,700-square-foot wooden chateau of David Long, the CEO of Liberty Mutual, the Boston-based insurance company. He calls the place “Summer Wind.’’

Long has hired a bunch of high-priced lawyers to try to kill the project through assorted technical arguments even as the Board of Selectmen and most others on the island support it. Long doesn’t want the peasantry near him.

Long may be typical of the imperial executives who have been running companies (and now the United States) since the ‘80s – obsessed with maximizing their personal wealth above all else and wallowing in conspicuous consumption. They tend to have houses in places such as the Hamptons and Nantucket which, since crowded by other rich people, further inflates their self-importance.

Long was paid about $20 million last year, and, as The Boston Globe famously noted, $4.5 million was spent to renovate his 1,335-square-foot office (throne room?) at Liberty Mutual.

Such folks are making Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard boring. They’re building a Greenwich, Conn., on sand dunes.

Amidst kitsch and the drive to show off, a Quaker aesthetic still survives in the prepster Brigadoon

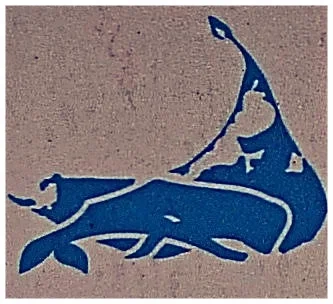

The Nantucket Island license plate appropriately displayed on a Land Rover, a classic off-road SUV for navigating Nantucket's cobblestone streets.

Can the precious island made wealthy by Quaker ship owners and whalers, but now the purview of Ralph Lauren-clad hedge-funders, stand any more cuteness? Would that the hauntingly beautiful island rebel against yet more trite merchandising of this demi-paradise of cedar shingles and windswept moors. Once, the ultimate status symbol was an over-the-sand permit for the bumper of a Jeep, or better yet, an old Land Rover. Now the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has offered another bit of snobbery with a special license plate.

Even so, the new plate is not nearly as exclusive as the various out-of-state vanity plates that are seen on the island. Imagine the pride of the Mr and Mrs Gottrocks, summer residents from somewhere near the horse country of Morristown, N.J., constantly announcing their second domicile on their Audi "Afrika Korps" urban assault vehicle.

Clearly the appeal is for more than the 10,000 or so locals, and anyone across the state can get a Nantucket Island plate for their car. It is a desirable trinket for those who regard the Far Away Land as nirvana – a place of Nantucket baskets, Nantucket red khakis, red brick sidewalks, and more take offs and landings at the airport in the summer than Boston's Logan. $28 of the island plate's $40 fee does go to non-profits that help children, but one wonders if there were not another way to raise charitable contributions than a design that pimps the island's history

Massachusetts paid a Boston brand consulting firm in Boston to glop up a license plate with several fonts. Thank goodness, the identifying NI and numbers are embossed – other states would have offered a tableau of Moby Dick in full-on Nantucket sleigh-ride mode. But no kudos should go to Nantucket artist David Lazarus for his confusing and complicated logo of a sperm whale superimposed on a detailed map of the island.

Such silliness makes a mockery of the centuries-old Quaker aesthetic that gave Nantucket such a strong design identity,as in the house below.

William Morgan is a contributing editor at Design New England magazine and is the author of such books as Yankee Modern and The Abrams Guide to American House Styles.

Linda Gasparello: A Mass. man in full

Ralph Marcy Gasparello

This is about my father, Ralph Marcy Gasparello, who died on July 11, aged 88. He was a stalwart resident of Hingham, Mass. Indeed, he often boasted about his status as “maybe the longest resident” of the town.

He had many opportunities to leave Hingham, especially after the death of his wife, Joan, in 2005. But he loved the town and their elm tree-canopied house -- which he largely built -- and where he raised four daughters and a son.

He and his wife were players in that championship season of residents who moved to Hingham in the early 1950s, and contributed to the desirability that it has today as a South Shore town. The young married couple supported the town's planning, enlarging its schools and raising the educational standards (particularly Wilder Memorial Nursery School and South Elementary School), and the building of the new Hingham Public Library.

He was a Massachusetts man through and through. He grew up in and around Boston, but mostly in Malden. He attended Boston Latin and other schools before graduating from Malden High School, in 1945. He was president of his high school class, and captain of its football team.

His athleticism won him a place on the football team of Cornell University, where he attended its famed school of hotel administration on an ROTC scholarship, and graduated in 1951, after completing his Army service. He married Cornell alumna Joan Rita Circola, of Brooklyn, N.Y., in 1952 at the university's Our Lady Chapel. They moved to Hingham in 1953.

He had a natural talent for public speaking, which caught the attention of his professors at the hotel school. While he was recruited by the Armstrong Cork Co. upon graduation, a speech that he gave on self-employment in a business class at Cornell sold him on that path in life.

When he and his wife moved to Hingham in 1953, he was working as a meat broker in Boston, having learned the business from a family member. He had a knack for sales because he liked to talk and listen to people: a skill honed during his days as a bartender at Cornell's Statler Club, where he learned to make his signature Negroni cocktail.

He stayed in the meat-brokerage business for more than three decades, until Iowa Beef Processors irrevocably changed the playbook for meat brokers in Boston in the 1980s.

A love for travel and languages – he spoke restaurant menu-level French, Italian and Spanish, which he and his wife studied at night for years at Hingham High School – led him to form an association for senior travel planners in 1985. He, his wife and his son, Ralph Jr., ran the National Association for Senior Travel Planners, and built it to 50,000 members before its dissolution, in 2001.

Through the association, he and his wife traveled widely. They enjoyed the business, and he especially enjoyed his public speaking – and even singing – opportunities during their Senior Travel Days shows. After his wife's death, he continued speaking in public – to those who attended the book lectures that he sponsored at the Hingham Public Library in memory of his wife, and to UBS investors forums.

His message to these and any audience -- of one or many -- was always positive. As he once said, quoting actress Audrey Hepburn, “Nothing is impossible, the word itself says 'I'm possible.'”

He had wide interests, including an abiding one in his college alma mater. He and his wife were active participants in the Cornell Club of Boston and Cape Cod. For years, they interviewed prospective students from the South Shore.

His appreciation of music was passionate and all-genre – from Big Band to bluegrass to salsa and classical. It never dimmed, even though his hearing did in his final decade.

He was a natural athlete and could do anything with a ball, and watch any sport. He could cane chairs, which was his way of passing long New England winters. “I like to be busy,” he used to say.

He was a reader and relished discussions of domestic and foreign affairs. He wrote poetry.

He was an accomplished cook, especially Italian food, and loved to “get dirt under his nails” (as did his father) in the gardens in his homes in Hingham and on Nantucket Island.

He was Big Ralph to his family and friends. He was tall in stature and big in his love of life and this world. He had a big heart, which finally failed and took him from us.

He is survived by three daughters and a son, Linda Gasparello, of West Warwick, R.I., Lisa Holt, of Newburyport, Mass., Nina Moore, of San Francisco, and Ralph Jr., of Merrick, N.Y., their spouses and seven grandchildren -- who called him Pops -- and other relatives. His daughter Paula Jordan, of Belton, Texas, died in 2012.

A private family memorial ceremony will he held on Nantucket Island.

Linda Gasparello is co-host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

William Morgan: The Quaker Coast

Photos (below) and commentary by WILLIAM MORGAN

It has been almost a decade since I published a book of photographs on the Cape Cod cottage. Since, then, I have been looking for another suitable topic.

My (more successful) photographer friends tell me no one is underwriting black and white photos taken with film. And my favorite publisher nixed the idea for a photographic study of what I call the Quaker Coast (the towns of Dartmouth and Westport in Massachusetts, and Little Compton, just over the border in Rhode Island), declaring that there would be no market for such a book.

Yet there is something special – and not yet ruined – about those three towns. Fishing and agriculture still survive, if not actually thrive, there. And the mostly unspoiled landscape and the prevalence of a plain vernacular architecture, mostly wrapped in cedar shingles.

In lieu of the fantasy book, I offer the readers of New England Diary three images from the book proposal.

Addendum: Much of Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket were also Quaker. I went to a few family memorial services in the Quaker meeting house in West Falmouth, on the Cape.

Many whalers were of Quaker background -- but that didn't make them gentle at all. Rather, many were tough and rapacious. Many became very successful capitalists whose investments spanned the world.

-- Robert Whitcomb