Llewellyn King: A way to greater leisure with same number of work hours a week

The American Federation of Labor union label, circa 1900

Labor Day is almost here and with it another blessed, three-day weekend. Three days without work!

The best day, of course, is the middle one, when we can luxuriate in the time off without the knowledge that grips most of us on Sunday afternoons — that we must climb Monday’s escarpment.

The fact is that we Americans work too much. Not necessarily too hard, but too much. In the United States, workers’ vacations are mostly two precious weeks — and a third after long service. In Europe, they’re a month or, as in Germany, often up to six weeks — yet no one accuses the Germans of being idlers or not performing.

We won’t get more vacations, I think, until high-tech workers — those one might refer to as “the indispensables” — demand and get them. Some already have the choice of working in Europe and are looking at the “package” of their employment, not just the dollars in the paycheck. If they demand more, the idea will get around.

However, more vacation days won’t have the same benefit as those leisurely Sundays in a three-day weekend.

There is a way to greater leisure with the same number of work hours in a week. I have experienced it, and it does wonders in terms of employee happiness and creativity.

In the early 1960s, I was a writer for BBC Television News, and we worked a fabulous shift system: three days on and three days off. This system recognized that journalists could seldom finish what they had started in a procrustean eight hours.

The BBC 10-hour shift — three days on and three days off — accepted and accommodated the reality of the work rather than trying to squeeze the work into an arbitrary time frame, leaving it either unfinished or for someone else to try to finish — say a script for the late news broadcast or coverage of an ongoing parliamentary debate.

The social dimension of this work structure was even more interesting. Writers and editors became more productive in other ways: Some wrote novels, others worked on biographies or tried their hands at plays. They’d been given the gift of time.

Armed with this experience, when I worked at the Washington Post, where I was an assistant editor and also president of the Washington-Baltimore Newspaper Guild, one of the largest chapters of the American Newspaper Guild, the trade union that represented journalists and some other workers, I was appalled at the mess the Post had with its overtime.

There was a complicated system of overtime and something called “overtime cutoff,” which applied to people who were paid more than the Guild-negotiated salary. It led to fights, conscientious reporters and editors working overtime without compensation, and major altercations over weekend schedules. No winners, just unhappy people. The management knew it was a mess and would’ve liked to change it.

When I suggested the BBC system to the Washington Post Company, management was enthusiastic. They asked if the union would bring it forward as a formal proposal in the contract negotiations, then just beginning for a new three-year contract.

We had to have our proposal vetted by union headquarters, the International. They said, “No, no, no. Heresy.” The union had always fought for a shorter workday since the so-called “model contract,” written by Heywood Broun, the famous reporter, columnist and founder of the American Newspaper Guild, in 1935. It was dropped like a libelous story.

Well, the three-days shift won’t work in many places, but in journalism, manufacturing and retail, it’s worth a try. Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of workers would have the joy of that middle day of rest and, maybe, creativity.

When you open another cold one on Sept. 1, think about how nice it would be if that happened all year. Three days on and three days off. Glorious!

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Labor Day morning

Sept. 1, 2014:

A sticky morning that reminds me more of July than September. Very quiet, as people sleep in for the holiday, storing up energy for the frantic fall of school, work, life in general. Some early leaf-fall. Gardens looking dry, and ugly weeds proliferate. Hordes of squirrels scurrying around for acorns. Automatic sprinkler systems watering the sidewalks.

It seems very American to celebrate Labor Day as part of a summer weekend rather than as a statement of working-class solidarity, as with May Day (May 1) in the rest of the world. But America is indeed increasingly a class-divided society.

I thought about the outbreak of World War II and, as many people do, of this poem by W.H. Auden.

September 1, 1939

I sit in one of the dives On Fifty-second Street Uncertain and afraid As the clever hopes expire Of a low dishonest decade: Waves of anger and fear Circulate over the bright And darkened lands of the earth, Obsessing our private lives; The unmentionable odour of death Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can Unearth the whole offence From Luther until now That has driven a culture mad, Find what occurred at Linz, What huge imago made A psychopathic god: I and the public know What all schoolchildren learn, Those to whom evil is done Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew All that a speech can say About Democracy, And what dictators do, The elderly rubbish they talk To an apathetic grave; Analysed all in his book, The enlightenment driven away, The habit-forming pain, Mismanagement and grief: We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air Where blind skyscrapers use Their full height to proclaim The strength of Collective Man, Each language pours its vain Competitive excuse: But who can live for long In an euphoric dream; Out of the mirror they stare, Imperialism's face And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar Cling to their average day: The lights must never go out, The music must always play, All the conventions conspire To make this fort assume The furniture of home; Lest we should see where we are, Lost in a haunted wood, Children afraid of the night Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash Important Persons shout Is not so crude as our wish: What mad Nijinsky wrote About Diaghilev Is true of the normal heart; For the error bred in the bone Of each woman and each man Craves what it cannot have, Not universal love But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark Into the ethical life The dense commuters come, Repeating their morning vow; 'I will be true to the wife, I'll concentrate more on my work,' And helpless governors wake To resume their compulsory game: Who can release them now, Who can reach the dead, Who can speak for the dumb?

All I have is a voice To undo the folded lie, The romantic lie in the brain Of the sensual man-in-the-street And the lie of Authority Whose buildings grope the sky: There is no such thing as the State And no one exists alone; Hunger allows no choice To the citizen or the police; We must love one another or die.

Defenseless under the night Our world in stupor lies; Yet, dotted everywhere, Ironic points of light Flash out wherever the Just Exchange their messages: May I, composed like them Of Eros and of dust, Beleaguered by the same Negation and despair, Show an affirming flame.

And some people, especially of a certain age, may remember the haunting old man's song, by Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson, "September Song,'' whose lyrics include:

"Oh, it's a long, long while from May to December "But the days grow short when you reach September "When the autumn weather turns the leaves to flame "One hasn't got time for the waiting game''

"September Song'' was written in 1938. Many sad songs were written in the late '30s, as the world, long in the Great Depression, moved toward another gigantic war. One was "Thanks for the Memory,'' which is funny and melancholic at the same time. It became Bob Hope's theme song.

The lyrics include:

"We said goodbye with a highball Then I got as 'high' as a steeple But we were intelligent people No tears, no fuss, Hooray! For us''

-- Robert Whitcomb

“There is no man, however wise, who has not at some period of his youth said things, or lived a life, the memory of which is unpleasant to him that he would gladly expunge it. And yet he ought not entirely regret it, because he cannot be certain that he has indeed become a wise man–so far as it is possible for any of us to be wise–unless he has passed through all the fatuous or unwholesome incarnations by which that ultimate stage must be preceded….We do not receive wisdom, we must discover it for ourselves, after a journey through the wilderness wich no one else can make for us, which no one can spare us, for our wisdom is the point of view from which we come at last to regard the world. ''

-- Marcel Proust

Robert L. Borosage: Help unions help middle class

Labor Day is supposed to be a celebration of workers, but it’s been a long time since workers have been celebrated — or for that matter, have had a reason to celebrate. That’s because the union movement that gave us this holiday is, at least numerically, a shadow of its former self.

If we really want to give workers something to cheer about, we need to revitalize unions. It’s no coincidence that prosperity was widely shared when unions were at the height of their power in the decades after World War II, and that inequality has soared as unions have been weakened.

That’s what I conclude in Inequality: Rebuilding the Middle Class Requires Reviving Strong Unions, a new Campaign for America’s Future report. My analysis tracks the simultaneous decline in the power of the labor movement and the fortunes of middle-class workers. It makes the case in simple terms.

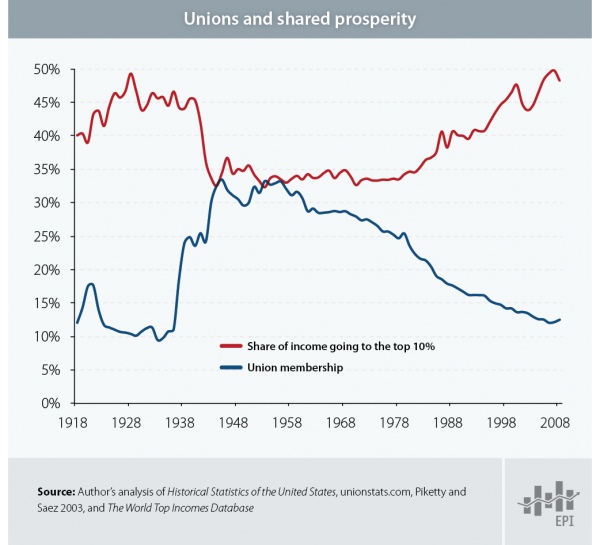

One chart reinforces the point. It compares union membership with the share of income going to the top 10 percent since the 1920s. When only one in 10 workers belonged to unions in the early 1930s, the richest 10 percent pocketed nearly half of the nation’s income.

Then President Franklin D. Roosevelt began a set of bold New Deal initiatives that dramatically increased the power of workers to join unions and bargain collectively. The share of workers who were unionized rose to about one-third by the late 1940s. At that point, the bottom 90 percent saw a significant increase in their share of national income.

Today, as union membership declines to low levels last seen in the 1920s, the share of national income going to the top 10 percent is rising — to levels not seen since then either.

Combine that with lackluster economic growth and you get the result chronicled in an August report by Sentier Research. As The New York Times reported, Sentier found that median incomes, when adjusted for inflation, had fallen 3.1 percent since 2009. They remain significantly below what they were in 2000.

A corporate-driven propaganda campaign has for decades blamed labor unions for saddling American corporations with burdens that made them uncompetitive in the global economy.

That has proven to be cover for dismantling the forces that kept corporations from rigging the economic rules in their favor. When corporate power was kept in check by union power, workers and corporations at least had a fighting chance to prosper together. Without that check, workers are losing. As wages erode, benefits disappear, work conditions become harsher and jobs themselves become more unstable.

The good news is that a combination of worker-activist movements and bold political leadership is setting the stage for a potential resurgence of the labor movement. In Los Angeles and other cities, newly elected pro-labor officials are making companies that benefit from local zoning or contracts pay a living wage and accept unions when a majority of workers indicate they want one.

Across the United States, fast-food worker strikes are fueling state and municipal minimum-wage increases while injecting new energy and ideas to worker organizing efforts.

President Obama has used executive orders to raise the minimum wage for federal contract workers and require adherence to basic fair labor standards, including the right to organize. These orders could have effects that ripple through to private sector workers.

Labor Day would live up to its purpose if it not only gave workers a temporary respite from the rigors of their jobs, but also drove a national effort to empower workers once again to rebalance the economic scales so that we can rebuild a growing, stable middle class. It needs to be a day on, not a day off, in the effort to reclaim the American dream for working people.

Robert L. Borosage is the co-director of the Campaign for America’s Future, a center for ideas and action that works to build an enduring majority for progressive change. Distributed via OtherWords.org