Austerity

“Coastal Rivers Walking Trail” (acrylic on panels diptych), by Jane Dahmen, at Portland (Maine) Art Gallery.

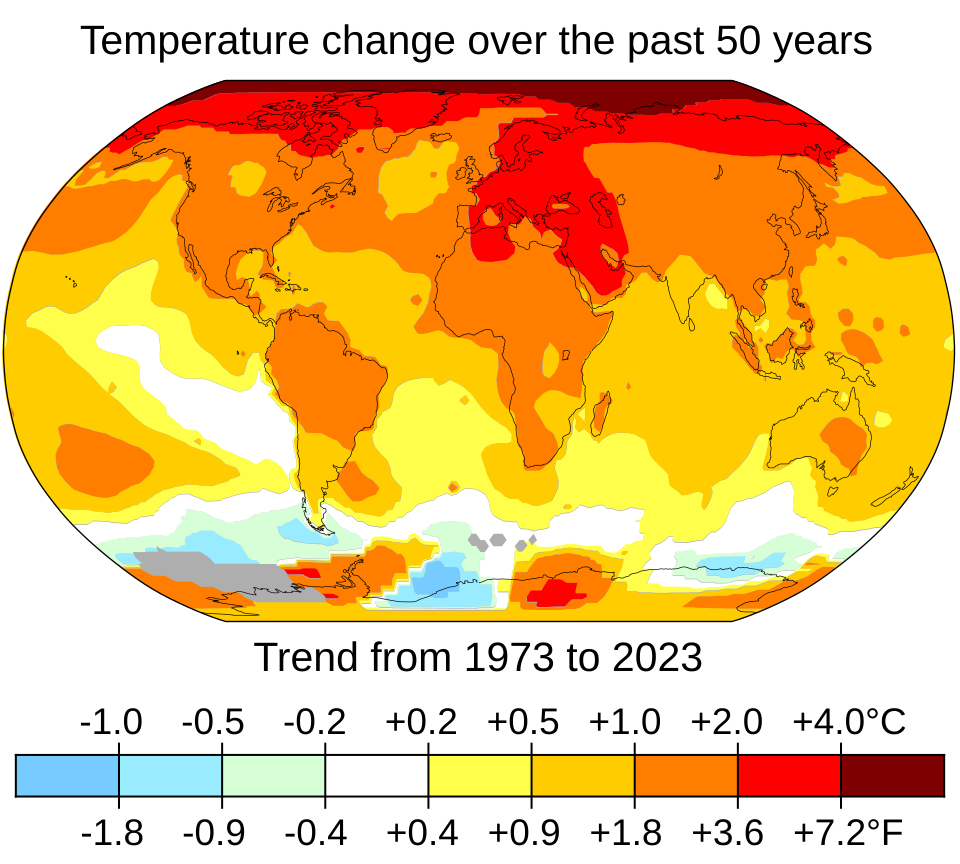

Gary W. Yohe: In America, how skepticism, dogma and big money respond to evidence for climate change

From The Conversation (not including image above).

Gary W. Yohe is a professor of Economics and Environmental Studies, Wesleyan University, in Middletown, Conn.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

Scientists are trained to be professional skeptics: to always judge the validity of a claim or finding on the basis of objective, empirical evidence. They are not cynics; they just ask themselves and each other a lot of questions.

If they see a claim that a finding is true, they will ask: “Why?” They may hypothesize that if that finding is true, then some related findings must also be true. If it’s unclear whether one or more of those other findings is true, they will do more work to find out.

It is no wonder that science moves so slowly, especially on really important topics such as climate change.

Dogmatism is the opposite of skepticism. It is the proclivity to assert opinions as unequivocally true without taking account of contrary evidence or the contradictory findings. It is why public debate over scientific findings never seems to go away.

An example of the difference is the reaction to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s finding in 1995 that “evidence suggests a discernible human influence on global climate.” The IPCC’s assessment reports involve hundreds of researchers from around the world who reviewed the global scientific understanding of the planet’s changing climate.

It’s an instructive case in the differences between skepticism and dogmatism, and it’s something to think about as you hear people talk about climate change.

Origins of a dogmatic response

Shortly after the IPCC released that finding in 1995, persistent and well-organized attacks on the science began. Many came from groups supported by the owners of Koch Industries, a conglomerate involved in oil refining and chemicals.

Their strategies mimicked earlier assaults on science and scientists who had warned the public that smoking posed a serious threat to their health. This time it was a warning about fossil fuels’ impact on the climate.

The similarity should not be a surprise. Science historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, in their 2011 book Merchants of Doubt, and American historian Nancy MacLean, in her 2010 book Democracy in Chains, have explained how the strategy was written by some of the same people who had tried to stop efforts to tighten tobacco regulations a decade or so earlier.

The dogma presented to the public for fighting regulation held that personal freedoms are paramount and that they are not to be diminished by any efforts designed explicitly to improve the general welfare.

What a skeptical response looks like

Climate scientists understood in 1995 that they must provide more than laboratory results, which go back to Svante Arrhenius’ work in 1895 demonstrating a causal correlation between increasing carbon dioxide concentrations and rising temperatures.

They also accepted the challenge of exploring collections of associated effects that should also be true if human activity was changing the climate.

Scientists have since examined dozens of different independently monitored aspects of climate change and confirmed the expected fingerprints of climate change all around the world.

Since the upper layers of the oceans absorb 90 percent of the atmosphere’s excess heat, they should be persistently warming as global temperatures rise. Has that happened? Yes, it has.

Since land-based ice melts when temperatures get too warm, global sea level should rise. And it should rise by more than would happen with thermal expansion of warming ocean water alone. Is it? Data shows that it is.

The major contributors to sea level rise. NOAA Climate.gov

Syukuro Manabe and Richard Wetherald argued in 1967 that the upper atmosphere should cool while surface temperatures rise in response to higher carbon dioxide concentrations. Has it cooled over the past 50 years? Yes, it has, just as Manabe predicted.

The upper atmosphere has been cooling while the lower atosphere, close to Earth’s surface, has warmed over the past two decades. The gray line marks the tropopause, between the lower troposphere and higher stratosphere. IPCC 6th Assessment Report

By 2021, as the evidence piled up, the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment stated: “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the global climate system since pre-industrial times. Combining the evidence from across the climate system increases the level of confidence in the attribution of observed climate change to human influence and reduces the uncertainties associated with assessments based on single variables. Large-scale indicators of climate change in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and at the land surface show clear responses to human influence consistent with those expected based on model simulations and physical understanding.”

Convincing the public

But has the public been convinced? The data on this are mixed.

Annual surveys conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication have found that the percentage of Americans “alarmed” about climate change rose over the past 11 years – from 15 percent in 2014 to 26 percent in 2024. And they show that much of that increase came from an increase in concern among Americans who earlier considered themselves “concerned” or “cautious.”

Over the same time period, though, the proportion of citizens in the survey who considered themselves “disengaged,” “doubtful” or “dismissive” shrank only modestly, from 29 percent to 27 percent.

Other surveys suggest that personal experience likely plays a significant role in how people understand climate change.

Many local and national news stations have mentioned climate change as a contributing factor in their extensive coverage of destructive wildfires in Los Angeles and Hawaii, flash floods in North Carolina and Texas, persistent drought across the Southwest, extreme heat waves and very destructive hurricanes.

Some of their viewers could certainly be coming around to believing what evidence shows: that climate-related disasters have become more frequent and more intense.

Americans are also directly experiencing other effects of climate change on their homes, health and wallets. For example:

Doctors in the North are seeing increasing cases of Lyme disease. Those in the South have been witnessing a rising number of cases of dengue fever. Both are spread by insects whose ranges are expanding as temperatures rise.

Lobster populations have collapsed in Long Island Sound and flourished farther north in Canada’s Bay of Fundy.

Residents in southern New England now enjoy feeding bluebirds in winter.

Homeowners across the U.S. are seeing their property insurance premiums quickly rise as disaster risks increase. Many others can’t get coverage from insurance companies at all because of their area’s disaster risks.

Stories like these do not make the national news very often, but they do show up in conversations around the kitchen table.

Reaching those with dismissive views

So, how can those Americans who are dismissive of climate change be reached? Some dogmatically believe claims that “climate change is a hoax” despite ever-growing evidence to the contrary.

Talking about personal experiences with extreme weather events, wildfires or droughts and their connections to rising global temperatures can help.

It might also help to remind them of failed dogma from the past that was disproved by science, yet people continued for years to believe them. For example, we know today that the Earth is not flat, the Sun does not circle the Earth, and living organisms cannot materialize spontaneously from nonliving matter.

The shift in public perceptions of climate risks leaves me hopeful that more people are acknowledging the scientific understanding of climate change and catching up with the climate scientists who have produced, questioned, reexamined and reaffirmed their findings through rigorous application of the scientific method.

Up in smoke

— Photo by Tomasz Sienicki

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com.

I remember with some distaste the adult New Year’s Eve parties of the ‘50’s and ‘60’s in my rather John Cheeverish Boston suburb.

My siblings and I and other young people were deputized to pass canapes to folks, some of whom were getting wasted on whiskey and gin drinks (hardly anyone drank wine then) as the ashtrays filled up (most adults smoked), and somebody played a piano, occasionally accompanied by off-key and sometimes funny, sometimes maudlin, singing. Or they just put on an LP record.

But I don’t remember seeing people wearing lampshades on their heads – the classic idiotic figures at a too-long Christmas party as presented in the movies and on TV back then.

The next morning, the bitter smell of cigarette smoke still hung in the living room. No matter how cold a New Year’s Day morning was, it was good to get outside and hope that the new year would be cleaner than the last.

The parties faded as the 60’s deepened and AA recruited more than a few of the celebrants.

Short but important

The summit of Mt. Monadnock, in Jaffrey, N.H., one of the world’s most climbed mountains and beloved by New England writers.

It’s only 3,166 feet high but dominates its region of southern New Hampshire. It gave the term “Monadnock’’ to geologists to describe any isolated mountain formed from the exposure of a harder rock from the erosion of a softer one once surrounding it (a landform termed “inselberg" (“island-peak") elsewhere in the world).

— Photo by LegalSmeagolian

Contemplating genius

“Vermeer: Woman Writing a Letter With Her Maid,’’ by Joe Fig, in his show “Contemplating Vermeer,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art through Jan. 11.

The museum explains:

“In 2023, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam hosted a monumental exhibition of Johannes Vermeer, showcasing 28 of the 35 masterpieces attributed to the enigmatic Dutch painter. Drawing on his own visit to this historic show, artist Joe Fig created a body of new paintings. In these works, featured in ‘Contemplating Vermeer,’ Fig not only pays homage to the 17th-Century painter’s mastery of light, color, and verisimilitude, but also reflects on the aesthetic experience in the Rijksmuseum’s galleries. Expanding on his decade-long ‘Contemplation’ series, he captures his subjects—artworks and their viewers—and their surroundings, exploring how people engage with or contemplate artworks in public spaces.’’

Taking education to the woods

URI students in the university’s North Woods program.

Excerpted (except f0r picture above) from an ecoRI News article by Bonnie Phillips

KINGSTON, R.I. — What do you get when you take a 300-plus-acre parcel of undeveloped woodlands with a walking trail and add high-tech flourishes such as an augmented reality walking tour and explanatory maps?

You get the North Woods at the University of Rhode Island — an outdoor classroom used to teach ornithology, herpetology, entomology, wetland ecology, environmental writing, art, and science communications.

“Really, everything is studied here,” said Madison Jones, an associate professor in URI’s departments of Professional & Public Writing and Natural Resources Science.

On a recent walk along the Blue Trail in the woods, which are in the northern part of the campus off Flagg Road and make up 25% of the university’s 1,200-acre total, Jones was almost evangelical about the educational possibilities of the North Woods.

Here’s the whole article.

Ghosts

‘‘Untitled’’ (oil, conté crayon, pastel on paper), by Norman Lewis (1909-1979), at The Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine.

Chris Powell: Asking the able-bodied to work in exchange for state help is reasonable

Official portrait of President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904 by famed painter John Singer Sargent.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Theodore Roosevelt, who in his time was often considered good liberal authority, noted that the first duty of a citizen is to pull his own weight. Only then, Roosevelt said, can a citizen's surplus strength be of use to society.

So it is strange that so many people who consider themselves liberals are horrified by the new federal law that sharply limits food subsidies for able-bodied single adults who aren't working. The liberals shriek that new rule may eliminate food subsidies for as many 36,000 people in Connecticut unless they can show they are working at least 80 hours per month.

What's the big deal about that? Eighty hours per month is not even 20 hours per week. Any able-bodied single adult who can't work 20 hours per week to support himself and thereby earn his government food subsidy needs a lot more motivation to stop being a burden on society and to start pulling his own weight.

But government in Connecticut is not in a good position to scold people for shiftlessness when it long has been running up the cost of living -- even putting hidden taxes on residential electricity -- and thereby discouraging those who already may be down on their luck, demoralized, or lacking job skills, as many socially promoted graduates of Connecticut's high schools lack them.

Indeed, as the state's rising cost of living pushes many people toward poverty and even homelessness, state government should be providing the destitute with more than food -- but in exchange for work. State government should be providing them with emergency, barracks-type housing and jobs with which they can begin to earn their benefits until they can live on their own -- an arrangement like the town farms of old.

The key would be to push people toward self-sufficiency and away from the demoralization that welfare causes and the irresponsibility that leads to welfare dependence.

Such a system would not solve the problems of the many homeless people who are chronically mentally ill. But at least enough barracks-type housing would allow them to get off the street during cold weather, to bathe and use a toilet, and have a little privacy, a prerequisite of sanity.

As a matter of fairness only state government can take responsibility for those who aren't taking or can't take responsibility for themselves. Municipalities and churches don't have adequate resources for this.

New Haven particularly is overwhelmed by homeless people, many mentally ill, who, along with their advocates, are pressing city government to open more shelters, which will draw still more homeless and mentally ill people to the city.

One of those advocates was quoted last week as saying it's “immoral" that New Haven “doesn't have a plan to ensure that everyone has a guaranteed right to shelter throughout the winter." Mayor Justin Elicker replied that the city does more for the homeless than any other municipality in the state -- that the city maintains seven shelters and spends $1.5 million per year on the homeless.

The mayor might have asked: When did New Haven and its taxpayers become responsible for all the region's homeless and mentally ill?

While a homeless man died overnight on the New Haven Green this month, at almost the same time two homeless people died outdoors in Stamford. This is a statewide problem -- an estimated 800 people in Connecticut are living outdoors and 3,000 in shelters, and more than 130 homeless people have died while living outdoors in the state this year. Now that it's cold, shelters usually have to turn people away because they are full.

The homeless and uninstitutionalized mentally ill constitute an emergency. Connecticut needs a government agency to take them all in hand -- to ensure not just that they can get state medical insurance and food but also that they can have a cot in a safe barracks, and that they are required to do some work to cover their expense and accept their responsibility to pull their own weight.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Linda Gasparello: Holiday postcard from the mighty Queen Mary 2: Fantastical food and agile ancients

The gigantic Queen Mary 2. Except for image above, photos are by Linda Gasparello

My husband, Llewellyn King, and I chose a Christmas-to-New Year’s cruise on the Queen Mary 2, titled Caribbean Celebration, because there were so many days at sea. We love the feelings of lethargy, languor and disengagement that fill us on those days.

But the sea days — and there were three since we left New York on Dec. 22 — were an irritant to the few children on board who couldn’t wait to get to our first port of call, Charlotte Amalie, on St. Thomas, the capital of the U.S. Virgin Islands. I think that the prospect of visiting Blackbeard’s Castle on the island was beating out the visions of sugarplums dancing in their heads.

There has been no shortage of sugarplums on the QM2, both edible and inedible. For this cruise, the pastry pros in the galley have rolled out some inspired creations.

Gingerbread housing development.

On Deck 3, as you walk to the Britannia, the main dining room, there is a corridor-long gingerbread village. Look but don’t pinch off a piece of the white icing-covered picket fence, passengers are gently asked.

At lunch in the King’s Court Buffet on Christmas Day, passengers’ eyes popped at the festive dough decorations and ice sculptures, and shirt buttons popped after eating many helpings of the desserts. They piled plates high with thick slices of cakes — including Black Forest and Bûche de Noel.

I stopped an English lady before she tried to cut into a square cake frosted with royal icing. It was part of one of the buffet decorations.

“That is a fake cake,” I said.

“I saw a German cake, a French cake, but no Christmas cake,” she sighed.

I love that traditional British cake, too. It is packed with dried fruit and plied with brandy or rum for weeks, then covered with a layer of marzipan and royal icing.

I sighed for a second, then I spied mountains of colored marshmallows on a nearby table. I hoped that there would be piles of Turkish delight, for which I have a passion. Sigh, no. In consolation, I snagged a couple of Quality Street toffee pennies.

The galley chefs have accommodated passengers’ varied tastes and dietary restrictions admirably. But in keeping with The Cunard Line’s British heritage, every day they have offered a full English breakfast (fried eggs, back bacon, Cumberland sausages, mushrooms, tomatoes, black pudding and toast — sigh by some, no fried bread. At lunch, there has been a carvery table with two kinds of roasts, a meat or vegetable stew, various curries, battered cod and chips, even Cornish pasties and small beef and mushroom pies. Sigh by my husband, no beef and kidney pies.

On Dec. 26, Boxing Day, Llewellyn and I met the ship’s chef de cuisine, Willy Guilot. He is a Filipino and has worked on the Queen Mary 2 since she entered service, in 2004. We complimented him on the quality of the meals. He said that the work had been “crazy” in the galley over Christmas, but he high-beamed at our recognition of it.

For Christmas Day dinner in the Britannia, I chose the traditional turkey with chestnut stuffing and Mrs. Beeton’s Christmas Plum Pudding. I think that Isabella Beeton, the Victorian journalist and author of Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, which is more commonly known today as Mrs. Beeton’s Cookbook, would have ordered it. She might even have licked what was left of the pudding and the custard sauce on the plate.

On my way out of the dining room, I passed by a table where the English lady I had met at lunch was sitting. She smiled at me and pointed to her dessert plate, on which there was a crumb of pudding and a drop of custard sauce.

*****

Rudolf Nureyev, the ballet superstar, said, “You live as long as you dance.” Judging from the median age on the elegant Queen’s Room dance floor every night at 9, he got that right.

Agile ancients having a fine old time.

Last night, the QM2 band played swing music and the floor was alive with pairs of agile ancients dancing all the styles, including the Lindy Hop and the Jive. They had all the moves and the clothes, especially the ladies: They wore full, flowing skirts for twirling.

As they walked off the floor, my husband and I thought that they would return to their seats and order a belt. But no, they did about-faces when the band leader said, “You may not want to take your seats, because we’re going to play Benny Goodman’s ‘Sing, Sing, Sing.’ ”

We saw a Chinese couple from Toronto, who we have watched dance on other nights in the Queen’s Room, and have gotten to know, return to the floor.

At lunch today, the 86-year-old husband told us that he and his wife have taken ballroom dancing for 14 years with a Russian teacher. His wife said, “She is very strict.”

Six months ago, they both had a fall, but they were determined to dance aboard the QM2 this Christmas and New Year’s. So they danced gently for rehabilitation, but were told not to waltz.

I saw them waltzing one night and assured them, “What happens on the Queen’s Room dance floor, stays on it.”

He said, “My grandmother said, ‘When you are 60 you live in terms of years. When you are 70, in months. And when you are 80, in days.”

I added, “When you are 100, in minutes.” They laughed, a little.

They said they want to dance their 80s away — and next Christmas and New Year’s on the same cruise.

Quite unlike cruises we have taken on other lines, the many Chinese couples, young and old, on the QM2 are on the dance floor but not at the gaming tables. Every night, they are in heaven, whether dancing cheek to cheek or in the mood to jitterbug.

Linda Gasparello is producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. She’s based in Rhode Island.

Playful or ominous?

“Quack and Other Feelings,’’ by Fanny Brodar, at Morrison Gallery, Kent, Conn.

Arrogant ignoramuses

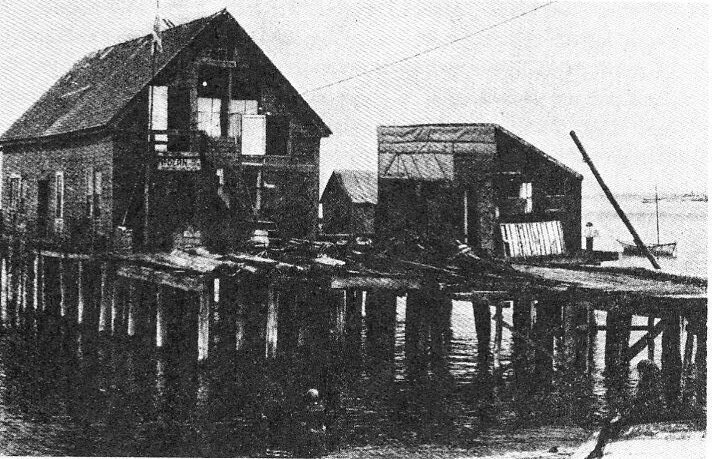

Lewis Wharf, the first home of The Provincetown Players, in 1915.

“From those who have never sailed come the quickest and harshest judgments on bad seamanship.’’

—Susan Gaspell (1876-1948), American playwright, novelist and actress. She and her husband, George Cram Cook, founded the revoluti0nary Provincetown Players.

‘We are Nipmuc’

Photo by Scott Strong Hawk Foster, in the show “Ways of My Ancestors: We are Nipmuc, We are the freshwater people,’’ at the Springfield (Mass.) Museums, through Jan. 4.

The museum explains that Scott Strong Hawk Foster is a Black-Native American photographer whose roots include Nipmuc, Mohegan, Blackfoot, and Cherokee lineage. “Scott’s images tell a story. They enable the viewer to feel the atmosphere, mood, and emotions of his subject in that moment. He endeavors to share his artistry and experiences through the lens of his camera.’’

Also part of the show is Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines Jr., a citizen of the Nipmuc people. “He serves as a cultural steward for his tribe, and is a father, public speaker, traditional dancer, activist for indigenous rights, carpenter and educator. Andre’s work focuses on bringing traditional knowledge back to indigenous peoples.’’

Territories of southern New England Native American tribes in the 17th Century.

Llewellyn King: In 2026, 70 percent effort should be enough

An ice sculpture for First Night in Boston

A remarkable autobiography by Anthony Inglis, the English conductor and musicologist, is titled, Sit Down, Stop Waving Your Arms About! Quite so.

This admonition occurred while Inglis was conducting a musical. Someone sitting in the front row tapped him on the shoulder and told him to sit down and stop waving his arms about.

My admonition to you for the new year is to sit down and stop stressing yourself.

We are plagued with the idea of stress, and yet we start the new year with resolutions. We order a raft of these stress-making endeavors.

Want a stress-free new year? Stop your New Year's resolutions right now.

Do you need to tell yourself that you will stay on your diet? No. You won't anyway.

Do you need to set a goal of going to the gym five times a week? No. You won't get to Planet Fitness more than once or twice, in the whole year.

So, your desk looks like a dump, leave it alone. You will promise yourself that for the first time ever you will get organized in 2026. You won't. So why get stressed about it?

You have promised yourself that this year you are going to improve your mind and read 20 great books. You won't. Best case, you will flip through a James Patterson thriller or a Danielle Steel romance. Maybe the detective novel you purchased at an airport will make it to your nightstand, alongside the classic you plan to read when you get around to it. That is never, so get rid of that reproving volume. Give it to charity. You will shed stress and feel good at the same time by doing that.

Sloth clothed as virtue is so, so stress-relieving.

Put aside the stress of resolutions in the new year and relax into a year of self-indulgence.

If a work colleague comes over to you and starts talking about productivity, cross your arms, sit down and, if your system allows, break wind.

Approach work as a card-carrying slough-off. In the Soviet Union, which was supposed to be the “workers' paradise,” workers used to say, “They pretend to pay us and we pretend to work.” Good on them.

If striving is pointless, stop striving. Give it a rest.

I suggest that there is a terrible national lack of malaise. At every turn, we are urged to learn more, work harder and innovate, innovate, innovate. You don't need innovation to have a second helping, open a beer or take the day off.

You may need to be a little innovative, explaining why you aren't at work. But that isn't so hard: Claim a mental-health day. Particularly if you are well and fit enough to enjoy it at the beach, at a movie theater or snuggled down into your bed.

If people are telling you to “lean in” and “try harder or the Chinese will get ahead,” go to dinner at a Chinese restaurant and wonder at the number of dishes which can be prepared almost instantly — none of which you would cook. Then conclude that the Chinese have already won and stop stressing.

Think back to when we stressed mightily about the Japanese and the Germans beating us at everything. Then enjoy a suffusing, warm gladness when you realize that all that leaning in and trying harder hasn't helped them beat us. Maybe we should have a national academy for failing upward.

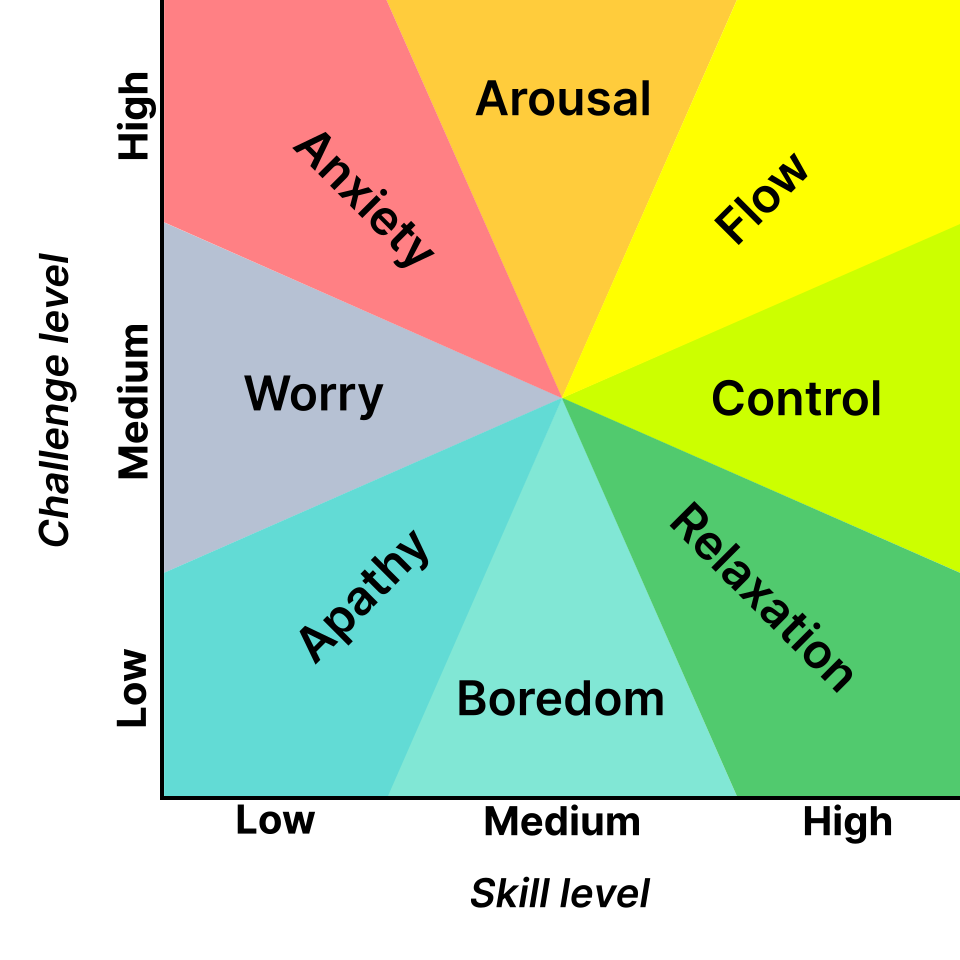

Lloyd Kelly, a fine artist and a friend, teaches Tai Chi in Louisville, Ky., particularly in one of the city's hospitals. He advises his students — some of whom are in wheelchairs — to stay within their comfort level, “to give just 70 percent.”

There is something beautiful about that admonishment at a time when people are stressed out and society is mindlessly urging you to struggle, to achieve, to conquer.

Here, then, is a resolution you can keep: I am only going to give a 70 percent effort. That way, perchance, you will have a great new year by default.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island.

‘Never seem to leave’ (with video)

“Maine Headland, Winter” by Rockwell Kent (1882-1971)

“Maine winters creep in like a python on little cat feet, take years to squeeze the life out of you, and never seem to leave.”

— Robert Karl Skoglund (1936-2024) (aka “The Humble Farmer’’), Maine-based humorist, columnist, radio personality and musician. He was born in St. George, Maine, and died there, too.

Seal of the town of St. George, Maine

Everybody on board!

“The Raft (after Gericault)" (walnut ink and acrylic on paper), by Nancy Hall Brooks, in the show “Plus One: Bromfield Artists Plus Their Invited Guest Artists,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Feb. 4-March 1.

We can try

“Defying Gravity’’ (oil stick on board), by Kate Nelson, at Cross Rip Gallery, Harwich, Mass.

The holidays in Boston through the centuries

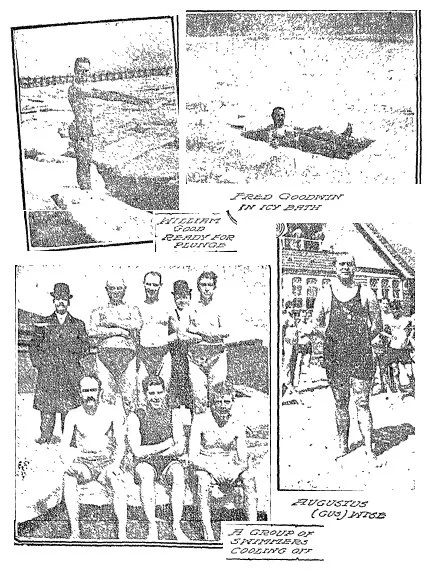

Photo montage of the L Street (in South Boston) Brownies published in The Boston Globe in 1913 under “Swimming Races for Brownies' Christmas Day"

From The Boston Guardian (except for image above):

(New England Diary’s editor/publisher, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Guardian.

On Jan. 1, 1701, Samuel Sewall, a prominent Boston jurist and Beacon Hill resident, distributed an ode to the new year and sent trumpeters to the Boston Common to herald the arrival of the hours-old 18 th Century.

Though festivities were often muted in colonial times, New Year’s 2021 will continue the celebration of a holiday that has been commemorated in Boston for hundreds of years.

In 17th Century New England, Christmas traditions were frowned upon, which caused some Bostonians to restrain their celebration until the new year.

Although Massachusetts operated on the Julian calendar, which put New Year’s on March 25th, many residents still commemorated the holiday on Jan. 1.

“It was illegal to celebrate Christmas during the Puritan ascendancy,” Peter Drummey, the Massachusetts Historical Society’s librarian, told The Guardian. “In some respects, they had New Year’s in lieu of the Christmas holidays.”

Still, New Year’s celebrations were minor in the colonies until the 19th Century, when droves of new immigrants arrived on American shores. Scots Irish newcomers brought with them a poem by Robert Burns called “Auld Lang Syne,’’ which they sang as the clock struck midnight on Dec. 31.

In 1863, amidst the devastation of the Civil War, thousands filled the Boston Music Hall and Tremont Temple to await the news from Washington, where President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which would free enslaved people living in Confederate states, was scheduled to go into effect.

Abolitionists such as Frederick Douglas and William Lloyd Garrison attended musical performances while a string of citizens stood between the concert halls and the telegraph office, ready to conduct the announcement to the anxious crowds.

“People who were ardent in the abolitionist cause had to see the news to really believe that it had happened; they had to have the proof,” Drummey said. “This was the only time that Boston had historically celebrated on a scale that we associate with New Year’s [today], but for reasons completely apart from the holiday.”

In the following decades, immigrants continued to arrive and change the annual traditions. Many were fleeing famine, revolution, or persecution.

“These people were bringing new traditions, new thoughts, and new beliefs,” Anthony Sammarco, a Boston historian, told The Guardian. “[Many] were looking to the new year to be better than the old one.”

In the 20th Century, other traditions developed, such as the annual polar plunge in Dorchester and ice skating at the Frog Pond. Immigrants from Latin American countries brought the practice of eating a dozen grapes at midnight. In 1976, artist Clara Mack Wainwright reinvigorated the city’s holiday by establishing First Night, a celebration that gathered musicians, artists, and revelers.

“Parkas and hiking boots on the Common…rocking saxophones in the frigid night air, thrumming guitars in the warmth of a Catholic church, champagne on Beacon Street, beer at Park Street Station, and vice versa,” reported The Boston Globe the following day. First Night grew each year, and by 1990 over a million people were attending the celebration, according to The Globe.

Emily Greene-Colozzi: There’s a lack of evidence that tech stops school shootings

Memorial flowers outside the Brown engineering complex, where the shootings happened.

Via The Conversation, except for the image above.

Emily Greene-Colozzi is an assistant professor of criminology and justice studies at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. She receives funding from the National Institute of Justice.

A group of college students braved the frigid New England weather on Dec. 13, 2025, to attend a late- afternoon review session at Brown University, in Providence. Eleven of those students were struck by gunfire when a shooter entered the lecture hall. Two didn’t survive.

Shortly after, a petition circulated calling for better security for Brown students, including ID-card entry to campus buildings and improved surveillance cameras. As often happens in the aftermath of tragedy, the conversation turned to lessons for the future, especially in terms of school security.

There has been rapid growth of the nation’s now $4 billion school security industry. Schools have many options, from traditional metal detectors and cameras to gunshot detection systems and weaponized drones. There are also purveyors of artificial-intelligence-assisted surveillance systems that promise prevention: The gun will be detected before any shots are fired, and the shooting will never happen.

They appeal to institutions struggling to protect their communities, and are marketed aggressively as the future of school shooting prevention.

I’m a criminologist who studies mass shootings and school violence. In my research, I’ve found that there’s a lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of these technological interventions.

Grasping for a solution

Implementation has not lagged. A survey from Campus Safety Magazine found that about 24% of K-12 schools report video-assisted weapons detection systems, and 14% use gunshot detection systems, like ShotSpotter.

Gunshot detection uses acoustic sensors placed within an area to detect gunfire and alert police. Research has shown that gunshot detection may help police respond faster to gun crimes, but it has little to no role in preventing gun violence.

Still, schools may be warming to the idea of gunshot detection to address the threat of a campus shooter. In 2022, the school board in Manchester, N.H., voted to implement ShotSpotter in the district’s schools after a series of active-shooter threats.

Other companies claim their technologies provide real-time visual weapons detection. Evolv is an AI screening system for detecting concealed weapons, which has been implemented in more than 400 school buildings since 2021. ZeroEyes and Omnilert are AI-assisted security camera systems that detect firearms and promise to notify authorities within seconds or minutes of a gun being detected.

These systems analyze surveillance video with AI programs trained to recognize a range of visual cues, including different types of guns and behavioral indicators of aggression. Upon recognizing a threat, the system notifies a human verification team, which can then activate a prescribed response plan

.

But even these highly sophisticated systems can fail to detect a real threat, leading to questions about the utility of security technology. Antioch High School in Nashville, Tennessee, was equipped with Omnilert’s gun detection technology in January 2025 when a student walked inside the school building with a gun and shot several classmates, one fatally, before killing himself.

School security technology firm ZeroEyes uses this greenscreen lab to test and train artificial intelligence to spot visible guns. AP Photo/Matt Slocum

Lack of evidence

This demonstrates an enduring problem with the school security technology industry: Most of these technologies are untested, and their effect on safety is unproven. Even gunshot-detection systems have not been studied in the context of school and mass shootings outside of simulation studies. School shooting research has very little to offer in terms of assessing the value of these tools, because there are no studies out there.

This lack is partly due to the low incidence of mass and school shootings. Even with a broad definition of school shootings – any gunfire on school grounds resulting in injury – the annual rate across America is approximately 24 incidents per year. That’s 24 more than anyone would want, but it’s a small sample size for research. And there are few, if any, ethically and empirically sound ways to test whether a campus fortified with ShotSpotter or the newest AI surveillance cameras is less likely to experience an active shooter incident because the probability of that school being victimized is already so low.

Existing research provides a useful overview of the school safety technology landscape, but it offers little evidence of how well this technology actually prevents violence. The National Institute of Justice last published its Comprehensive Report on School Safety Technology in 2016, but its finding that the adoption of biometrics, “smart” cameras and weapons detection systems was outpacing research on the efficacy of the technology is still true today. The Rand Corporation and the University of Michigan Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention have produced similar findings that demonstrate limited or no evidence that these new technologies improve school safety and reduce risks.

While researchers can study some aspects of how the environment and security affect mass shooting outcomes, many of these technologies are too new to be included in studies, or too sparsely implemented to show any meaningful impact on outcomes.

My research on active and mass shootings has suggested that the security features with the most lifesaving potential are not part of highly technical systems: They are simple procedures such as lockdowns during shootings.

The tech keeps coming

Nevertheless, technological innovations continue to drive the school-safety industry. Campus Guardian Angel, launched out of Texas in 2023, promises a rapid drone response to an active school shooter. Founder Justin Marston compared the drone system to “having a SEAL team in the parking lot.” At $15,000 per box of six drones, and an additional monthly service charge per student, the drones are equipped with nonlethal weaponry, including flash-bangs and pepper spray guns.

In late 2025, three Florida school districts announced their participation in Campus Guardian Angel’s pilot programs.

Three school districts in Florida are part of a pilot program to test drones that respond to school shootings.

There is no shortage of proposed technologies. A presentation from the 2023 International Conference on Computer and Applications described a cutting-edge architectural design system that integrates artificial intelligence and biometrics to bolster school security. And yet, the language used to describe the outcomes of this system leaned away from prevention, instead offering to “mitigate the potential” for a mass shooting to be carried out effectively.

While the difference is subtle, prevention and mitigation reflect two different things. Prevention is stopping something avoidable. Mitigation is consequence management: reducing the harm of an unavoidable hazard.

Response versus prevention

This is another of the enduring limitations of most emerging technologies being advertised as mas-s shooting prevention: They don’t prevent shootings. They may streamline a response to a crisis and speed up the resolution of the incident. With most active shooter incidents lasting fewer than 10 minutes, time saved could have critical lifesaving implications.

But by the time ShotSpotter has detected gunshots on a college campus, or Campus Guardian Angel has been activated in the hallways of a high school, the window for preventing the shooting has long since passed.