William Morgan: Book looks at metaphor, imitation, craft and continuity in architecture

One of the New England's most picturesque assets is the Greek Revival house, a sometimes brick but usually wooden structure with some classical details or perhaps even a portico, lining Main Streets and dotting the countryside. Aside from some legends about empathetic associations with Greece's war of independence, the application of a Doric column or the heavy lintel over the doorway was less politics than embellishment. Americans simply liked the style.

Temple form Greek Revival house in Winchendon, Mass., 1845.

— Photo by William Morgan

It is rather for architects and historians, such as Columbia University's Françoise Astorg Bollack, to parse the genealogy and meaning behind these temples of democracy. In her latest book, Material Transfers, Professor Bollack reminds us how the marble temples of ancient Greece were recreations of earlier wooden structures. While Americans built plenty of neoclassical civic structures, it was in the domestic realm that the wooden temple flourished.

The same kind of torturous evolution with multiple iconographic transferences can be seen in other styles, such as the Gothic Revival. A style that paid homage to the masonry forms of the pointed arch and the ribbed vault got translated into Carpenter's Gothic churches or cottages. Bollack also mentions cast iron, a revolutionary material that was molded with Renaissance details and often painted to look like stone.

Rotch House, A.J. Davis architect, New Bedford, Mass., 1845.

— Photo by William Morgan

The French-trained Bollack has done considerable restoration work, but Material Transfers: Metaphor, Craft, and Place in Contemporary is an attempt to redefine the meaning of contextual design. Rather than engaging in a century-old battle between modern and traditional – the angst of replica versus invention, Bollack suggests we discard an "outdated moral opprobrium." She presents us with at 22 projects characterized by "an unorthodox coupling and combination of forms."

Throughout, Bollack addresses such issues as metaphor, imitation, craft, and continuity ("Where are we to find a fresh place for 'the new' within the constraints of longed-for continuity"). The role of historic form in contemporary architecture, and how to respect the "continued validity of the traditional," are significant issues. But beyond the architectural theory, there is much delight to be found in the photographs of the "rich stew of hands-on trial-and-error research, collaboration between architects, manufacturers, and craftspeople."

Material Transfers is replete with serendipity, ingenuity, and the stretching of material limits. In Dairy House in England, glass lies between the horizontal wooden siding. An office block in downtown Copenhagen for a manufacturer of gold beads has a curtain facade of perforated copper that shimmers and changes color by night. A 14-story building in New York City looks just like its neighbors, except that it is made of pressed and carved glass.

The Dairy House, Somerset, England, Skene Catling de la Peña architect, 2007.

Such successful brainteasers include an abstract modern design for winery in Napa Valley, constructed of gabion (loose rubble constrained by wire fencing). A Paris town house is covered with a pixilated photograph of the building next door in a wood resin of the type used for road signs. Rammed concrete is the material of choice for a guest house added to a 1740 German vineyard.

Familiar forms inform many of these examples, but they are often realized in materials that seem wildly unfamiliar. Modernism's chief tenet of originality is stood on its head here, although many of the solutions respect tradition. This book's projects "begin to open the door to shift the discourse's center of gravity towards a more inclusive view of what 'making' is all about."

That said, anyone who is interested in contemporary architecture and how it can be integrated into historical settings, and invigorated with new, mostly non-polemical ideas will reap many visual rewards from this book.

One of my favorites from Material Transfers is the diagrammatical construction in welded galvanized wire mesh of an 1177 Italian basilica that was destroyed by an earthquake in 1233.

Basilica di Rete Metallicca di Siponto, Puglia, Italy, Edoardo Tresoldi architect, 2016.

But the project that really moves me is the Wadden See Center on the west coast of Denmark (the marshland is a UNESCO World Heritage Site) by the ever restrained and environmentally aware Danish designer, Dorte Mandrup. What at first appears to be a bold, modern statement is also a tribute to the local agricultural vernacular, and its roof and walls are surprisingly made of thatch.

Wadden See Center, Ribe, Denmark, Dorte Mandrup architect, 2017.

Françoise Astorg Bollack, Material Transfer: Metaphor, Craft, and Place in Contemporary Architecture, Monacelli Press, New York, 2020, $50.

Providence-based writer William Morgan has a degree in restoration and preservation of historic architecture from Columbia University. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

William Morgan: Cutting-edge artisanship at a family homestead in rural Maine

Hannah and Chris Blackburn outside their cutting-tool-making workshop, in New Gloucester, Maine

— All photos by William Morgan

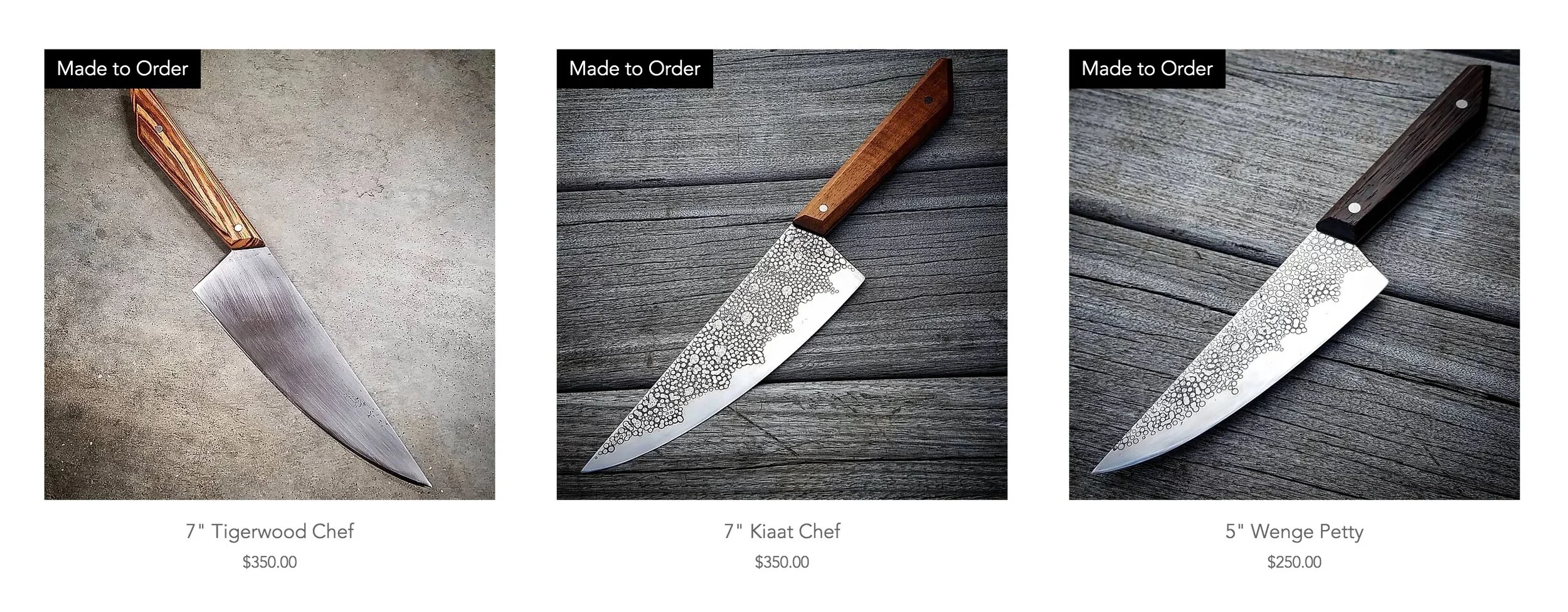

My wife recently bought herself a kitchen knife. Carolyn has dozen of blades suited to all kinds of cooking and pottery, including the stained and pitted Sabatier that she found at a yard sale a quarter century ago. But this piece of cutlery from Maine was different. It cost far more than she could afford, but it was so beautiful, such a work of art, that she could not afford not to buy it.

Really good tools should have stories. Carolyn's new extension of her hand was made of recycled materials: wood from Boston park benches and metal from old saw blades (the recycled 19th Century carbon steel is much stronger than anything available now, and its hard-earned patina is beautiful). That these artisanal tools are sold only at two stores –Strata in Portland and Stock in Providence – reinforces the fact that they’re the products of true craftspeople.

The Blackburns use the steel from old saw blades to make their artisanal knives and other cutting tools.

Full Circle CraftWorks is the commercial face of two art school graduates, trying to build a business while raising a family on a 22-acre homestead in New Gloucester, Maine, a quiet upland town close to, but very different from Freeport, best known for L.L. Bean and other stores, many of them outlets of national chains.

Hannah and Chris Blackburn met as undergraduates at the Rhode Island School of Design, where they were furniture and sculpture majors, respectively. They mastered such skills as welding and sculpting, along with traditional woodworking. Maine native Hannah grew up in nearby Yarmouth, while Chris hails from suburban Washington, D.C. After graduation, the couple remained in the Rhode Island capital.

Providence is a good place for young artists, with lots of colleagues and abundant studio space, but its urban setting was not what the Blackburns wanted for their growing family of two girls and a boy. "The goal was to carve out a simpler life," Chris says, "more directly connected to the environment, the seasons, and all things that sustain our life." One grace note is that the quest for a life based on the land while producing beautiful utilitarian objects is not so different from that espoused by the Shakers, whose last active colony, Sabbathday Lake, is close by in New Gloucester.

Carolyn Morgan and Chris Blackburn in First Circle’s workshop

Their 1985 log cabin on a dirt road came with a two-stall horse barn, which they converted into a workshop, complete with enough of the tools needed to fashion the exotic woods from around the world and the redundant saw blades from barns and country auctions into their handsome tools.

The future success of Full Circle would let these artists live from their sales, but right now their main goal is raising a family on what they hope will become a thoroughly sustainable operation. As a result, much of their life is focused on the rigorous, endless day-to-day and seasonal activities of a working farm.

Just a mention of the Full Circle’s livestock – three goats, seven ducks and a score of chickens, guarded by a dog to guard against coyotes, bears and other predators – ought to be reminder enough that self-sufficient farm life is far from simple or romantic. In the spring, piglets, turkeys and more laying hens augment the permanent stock. Bow hunting deer in the autumn provides much of the family's meat.

There is a small greenhouse, a fruit orchard and gardens for a variety of crops that will grow in Maine. The house and workshop are heated solely with firewood harvested on the property, where sugar maples are tapped to make syrup. Through all the seasons the three young children, aged nine, seven and five, help with chores, from planting and harvesting, to stacking firewood and feeding the animals.

Demanding as farm life is, it does not preclude the family's engagement with the local community. The Backburns host an annual July pig roast that draws scores of friends and neighbors. Their two daughters act in plays put on by the local youth theater, where Chris is a set designer and member of the build crew. The Blackburn children go to a Montessori-type charter school, even as important life lessons come from being part of the agricultural enterprise that helps sustain them.

A hand saw once used in Massachusetts apple orchard or a large circular blade from a Vermont sawmill, along with wood repurposed from repairing their cabin's porch or from an Indonesian rainforest, are transformed into utilitarian but strikingly handsome tools. Whether Hannah and Chris are fashioning a cleaver or a chopping blade, their handmade tools express a worldview that respects the land and the dignity of hard work.

When Chris saw Carolyn's knife again, he said, "It's getting good use; I can tell by the patina. I much prefer that. Some people see them as precious, but tools need to be used."

William Morgan, based in Providence, is an architecture writer, essayist and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village, in New Gloucester. It was founded in 1783 by the United Society of True Believers at what was then called Thompson's Pond Plantation. Today, the village is the last of some over two-dozen religious societies, stretching from Maine to Florida, to be operated by the Shakers themselves. It comprises 18 buildings on 1,800 acres.

William Morgan: A haunted grandstand in Pawtucket

The stands of what had been Narragansett Park

— Photo by William Morgan

Just off the unspeakably grim Newport Avenue strip, in Pawtucket, R.I., an abandoned colossus reminds us of once glorious days of thoroughbred horse racing patronized by swells from Newport and New York. This enormous structure was once part of a 200-acre complex with barns that housed 1,000 horses.

Narragansett Park opened in 1934, after the state’s official airport was declared to be Hillsgrove Airfield (now T.F. Green Airport), in Warwick, instead of Pawtucket’s What Cheer Airport, and pari-mutuel betting was reinstated after a 30-year ban; it folded in 1978 after a disastrous fire that killed three-dozen horses. The grandstand then became Building #19, the odd-lots warehouse, or "America's laziest and messiest department store," as its founder Gerry Elovitz dubbed it.

The slide from society amusement (thoroughbreds such as Whirlaway and Seabiscuit raced here on its mile-long oval), and a "Retail Derby" against the big-box stores, to inevitable decay, reverberates with the last days of our totally corrupt, would-be Nero-style emperor. Reminding us of Rome's Circus Maximus, home of the great chariot races, Narragansett Park's haunted grandstand is apt metaphor for the end of 2020.

William Morgan is a writer, architectural historian and photographer based in Providence. He has written on stock-car racing for The New York Times. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

Postcard photo of Narragansett Park in the 1950s

Work goes on after the storm

Southeastern New England’s first snowstorm of the month ended late in the day on Dec. 17, when the dramatic skies – looking like a 19th-Century Romantic landscape painting –announced a change in the weather. Life went on, as it always has during a New England winter. Two large ships were in Providence’s harbor: a tanker unloading oil to East Providence and the cranes on the other vessel being used to load something, perhaps scrap metal.

Photo and caption by William Morgan, a Providence-based writer and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter.

William Morgan: For creative responses to the graffiti challenge

After a seemingly endless rampage of city-blighting graffiti, the mayor recently announced that the police had finally identified and charged the most notorious tagger who "soiled hundreds of walls and buildings." The alleged culprit could get two years in prison for defacing property, "which had to be cleaned using public funds."

Dumpster on Providence’s Smith Hill.

— All photos by William Morgan.

This was welcome news, as most citizens regard as vandalism the bubble signatures and symbols painted on blank walls, mailboxes, dumpsters, and electrical boxes. Some lawmakers, however, protested that graffiti was a minor issue, while one accused the mayor of cracking down on graffiti as "a way to forge political consensus."

The mayor, however, is not Jorge Elorza of Providence, but the mayor of Rome, Virginia Raggi, and the alleged tagger was identified as “Geco” (no full name given).

But whether it's Providence or the Eternal City, the problem of such urban defacement is old as human settlement. The ancient Romans battled it, as did the Egyptians centuries before that. During World War II, American G.I.s' painted “Kilroy Was Here’’ on walls from Anzio to Guadalcanal. Like the poor, graffiti will always be with us.

On Ives Street, in Providence’s Fox Point neighborhood.

Called tagging, painting your name in bold letters on the side of a building or a railroad car is about self-expression. Free spirits, the rebellious, and the disenfranchised tag their names to declare that they exist. According to Paolo von Vacaro, an authority on graffiti, "You tag your name to show that you are king of the street."

Competing artists lay their claims to a Providence wall.

As with many forms of self-expression, one man's creative genius is another's vandalism. One might admire the styles of particular graffitists, or how practitioners have artistic duels on public walls. But when the walls are historical, such as Providence Marine Corps of Artillery Arsenal, on Benefit Street, in a section of the city known for its historic architectural beauty, then graffiti is, according to the City of Providence, "a public nuisance and destructive of the rights and values of property owners as well as the entire community."

Defacing the Arsenal, the David Macaulay mural on I-95, or the Providence River pedestrian bridge is unacceptable. If residents and business are really stung by tagging, then they should push the city to get really serious about apprehending the spray-can brigade, and mete out fines stiff enough to cover the restoration of damaged walls and objects.

But how much of a public nuisance is the run-of-the-mill graffiti that covers so many walls, particularly in less affluent neighborhoods? Does it threaten the commonweal? Does painting freight cars make them less efficient? Or are the giant bubble letters symbolic of deeper strains within the community?

Masterpiece of railroad freight car graffiti.

Visual pollution is as unfortunate as it is indefinable: a certain building may enhance or offend, one man's Christmas lights may seem tacky to his neighbors. Graffiti, like smut (the late Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart declared that he could not define smut, but knew it when he saw it), may be impossible to eradicate.

One of many injury law billboards.

If we are to tackle a city's visual pollution, why not eradicate the billboards that are a blot on the cityscape? As soon as you pass border signs admonishing you to “Discover Beautiful Rhode Island,’’ there are billboards touting one personal-injury law firm after another. (A traveler crossing Rhode Island for the first time might wonder if we do nothing here but chase ambulances)

Rocky and Bullwinkle mural visible from the train, by a 21st-Century Leonardo.

Why not a creative solution for the Creative Capital? If graffiti is a fact of city life, why not embrace it? The destruction of property should be discouraged by strict law enforcement, but the vibrancy of famous artist-provocateurs such as Banksy and Jean-Michel Basquiat should be encouraged. Why not embrace it?

How about hosting a graffiti conference and contest, where local talent and free-spirited geniuses from all over America would come to compete for a national title? Blank walls on warehouses, factories, and other structures would be donated. Providence businesses could sponsor walls, the Rhode Island School of Design could offer a residency for certain artists, and there could be conferences on tagging, along with publications, and maybe even art-school scholarships for disadvantaged would-be artists. Such an event could boost the city on many levels.

Many free-spirited paint bandits might balk at the contra-indication of control, so they would have to continue their vandalism as outlaws. But in the spirit of the successful Gravity Games of 1999-2001, let’s plan for some post-COVID-events that encourage fun, artistic energy, and above all, optimism.

“If your graffiti is exceptional, thank your art teacher’’ says my wife, Carolyn Morgan. Graffiti mural on North Main Street by Jasper Summers..

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian, essayist and photographer. His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

William Morgan: Raymond Hood and the drama of the American skyscraper

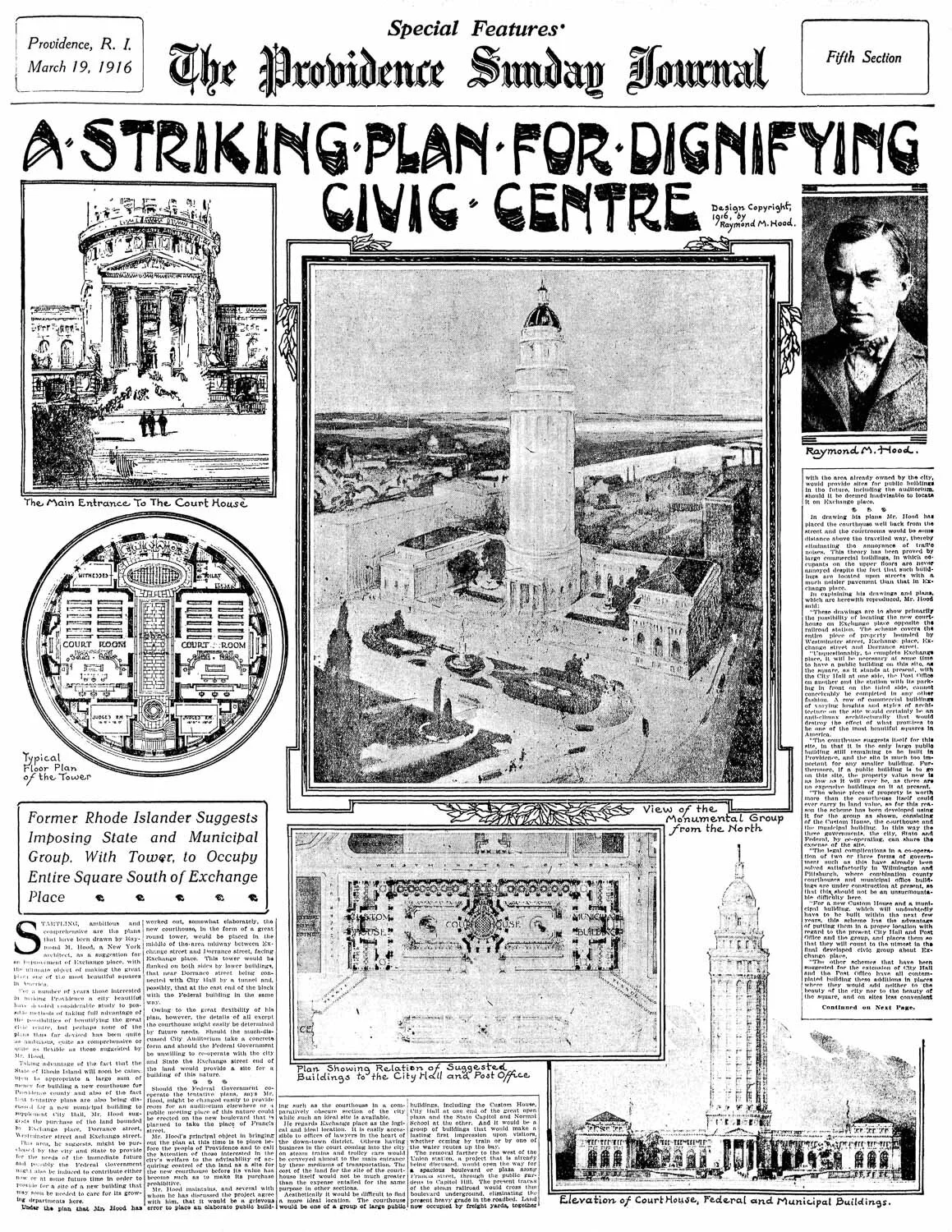

In 1916, a little known, 35-year-old architect and Rhode Island native proposed a monumental civic structure for downtown Providence. Raymond Hood's Civic Centre would have been sited where the Industrial Trust Building was later built; it was to be 600 feet tall and would serve as courthouse, library and prison. Its tower would symbolize progress and prosperity at the head of Narragansett Bay.

A few years earlier, Hood had done his thesis at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts, in Paris, on a design for a city hall for his hometown of Pawtucket. While neither of these fanciful schemes was built, they demonstrate the early vision of a man destined to become of one of the 20th Century's most significant skyscraper architects.

Raymond Hood, Proposed City Hall for Pawtucket. Year-Book of the Rhode Island Chapter, American Institute of American Institute of Architects, 1911

“Raymond Hood and the American Skyscraper,’’ an exhibition initially organized for showing to the public at the David Winton Bell Gallery, at Brown University, opened online only on Sept. 11. The show, underwritten by the Brown Arts Initiative and Shawmut Design & Construction, features loans of drawings and photographs from RISD, MIT, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania and the Smithsonian Institution. Hit this link to see the show.

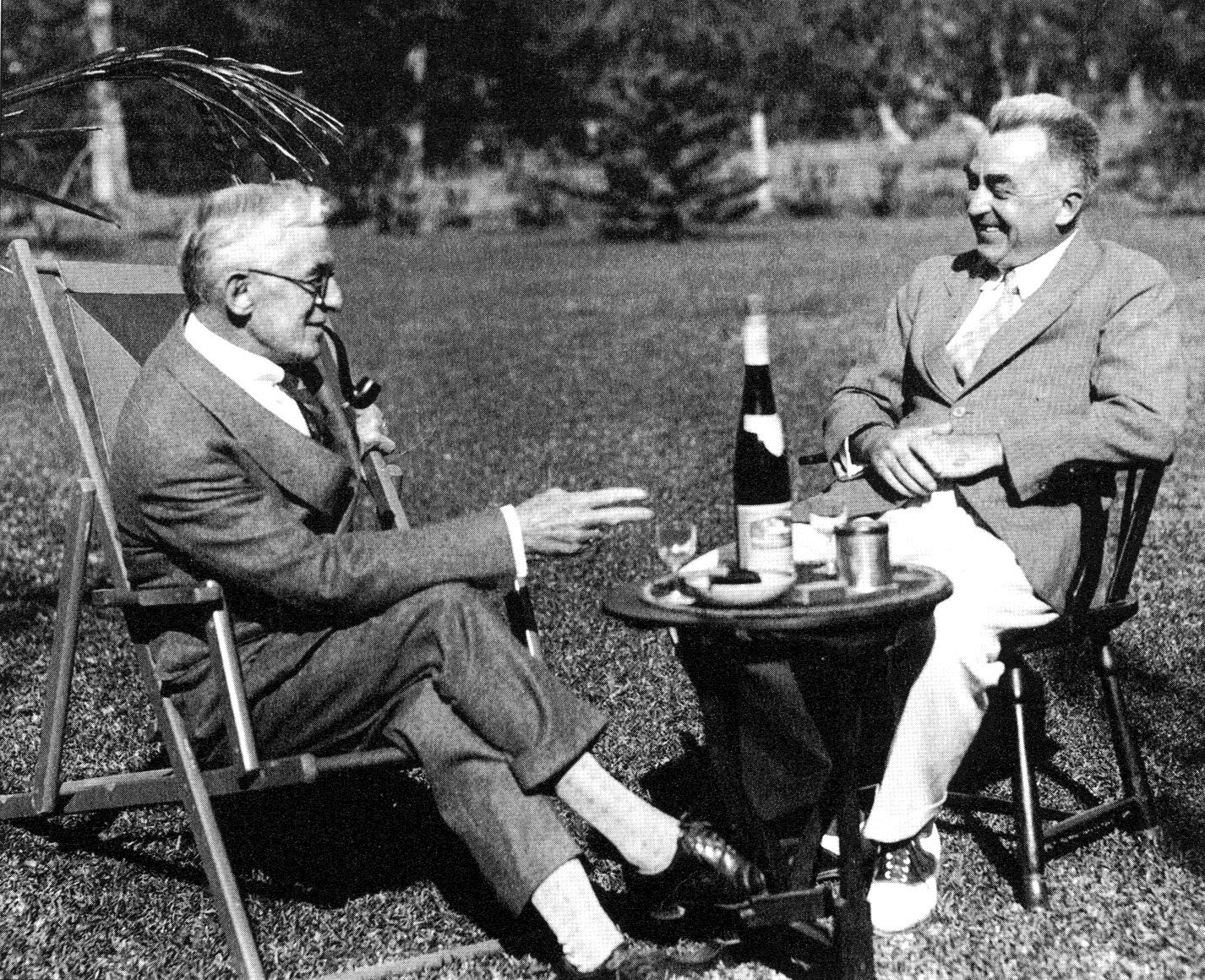

Ralph Adams Cram (left) and Raymond Hood in Bermuda, c.1930. Hood worked for Cram as a young architect; Cram designed the Pawtucket Public Library. Courtesy, Cram & Ferguson Architects

Beyond the lectures and other materials associated with the show, one can access information on Hood through the handsome 48-page catalog written by two of the show's co-curators, Prof. Dietrich Neumann and Brown doctoral student Jonathan Duval (the other curator is Jo-Ann Conklin, director of the Bell).

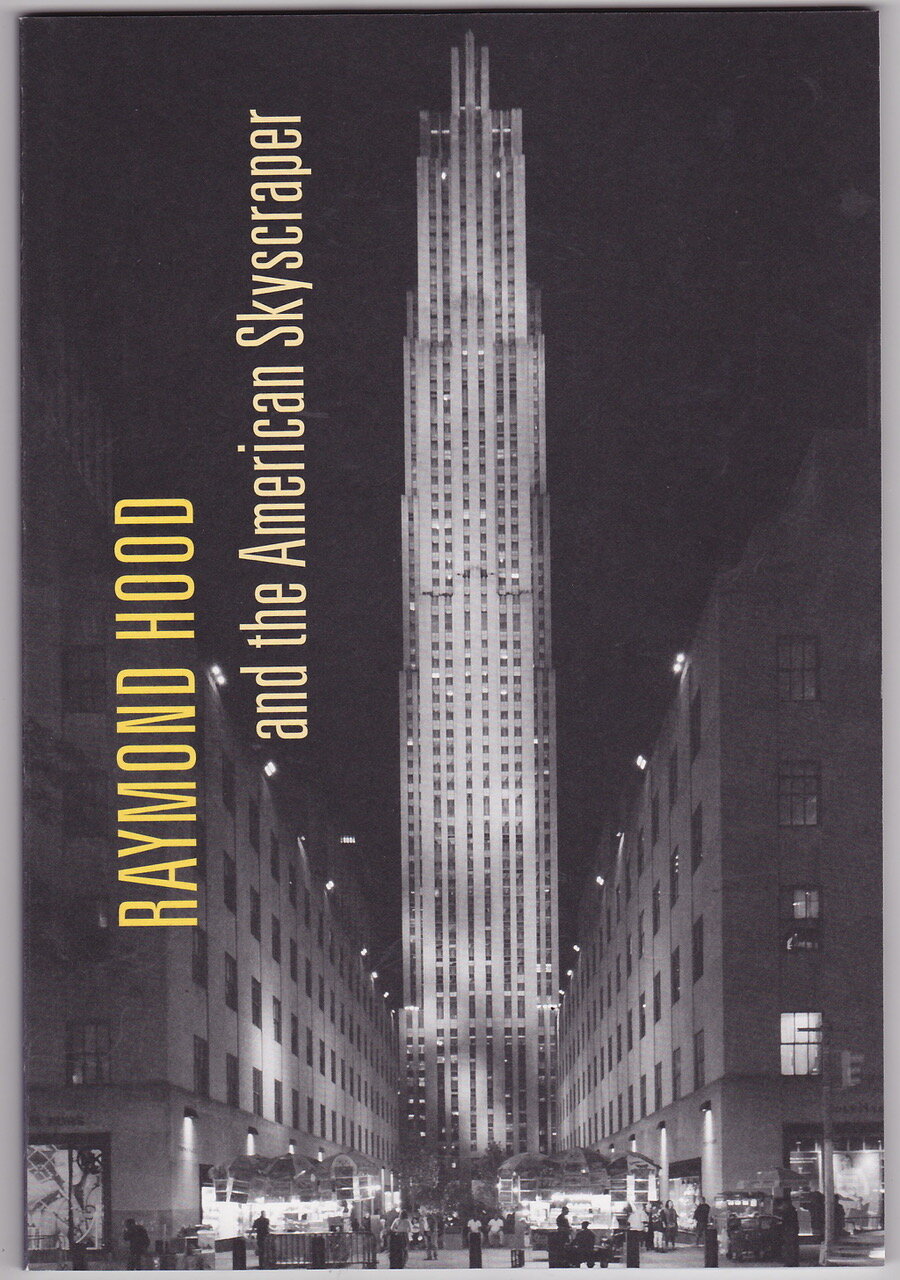

Catalog cover with Rockefeller Center, with the soaring RCA Building.

Hood would go on to design several iconic skyscrapers of the 1930s, serve as the head designer of Rockefeller Center, and would be, in Neumann's words "the most powerful architect in New York City." Significant exhibitions like this one reacquaint us with sometimes forgotten figures and force new assessments of their contributions to our cultural landscape.

RCA building at Rockefeller Center, photographed in 1933. Library of Congress.

Hood died far too young at 53. And in one of those ironies of architectural history, Modernists denigrated as too conservative the skyscraper that secured Hood's career and transformed him from dreamer to real player.

Howells & Hood, Chicago Tower. PHOTO ©Hassan Bagheri

As Neumann and Duval remind us, Hood was a struggling draftsman when he teamed up with the fashionable New York architect John Mead Howells (designer of Providence’s Turks Head Building) to enter the major international competition to build the Chicago Tribune's headquarters building in 1922. Howells and Hood beat out 262 other entrants from 23 countries with their skyscraper scheme.

I remember professors in college and graduate school ranting about the shortcomings of the Tribune Tower, labeling it "dishonest" for hiding its modern steel frame underneath a cloak of eclectic, historicist detail. It is time to acknowledge that Hood's design was the one that deserved to win, and to accept that the verticality of Gothic was wholly appropriate for such a soaring form.

Almost 100 years after that famous controversial contest, the Tribune Tower remains an absolute triumph, proudly standing in the skyscraper capital. Hood's more streamlined skyscrapers in New York – the RCA building, the Daily News Building and the McGraw-Hill Building – still inspire us, and they are especially instructive when placed against formless pieces of real estate such as Providence's proposed Fane Tower.

McGraw-Hill Building, New York, PHOTO © Hassan Bagheri

The effort that Brown has applied to the work of Raymond Hood is the sort of public service that universities offer the commonweal. Such scholarship is especially welcome now, as study of great architecture and urbanism is crucial to rebuilding after a time of pandemic.

Providence-based architecture critic and historian William Morgan has taught the history of architecture at Princeton University, The University of Louisville and Roger Williams University.

His latest book is Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter

William Morgan: When so many deaths were early

The Stonington Cemetery, in Stonington, Conn. The first burial in it was in 1754, with the interment of Thomas Cheseborough.

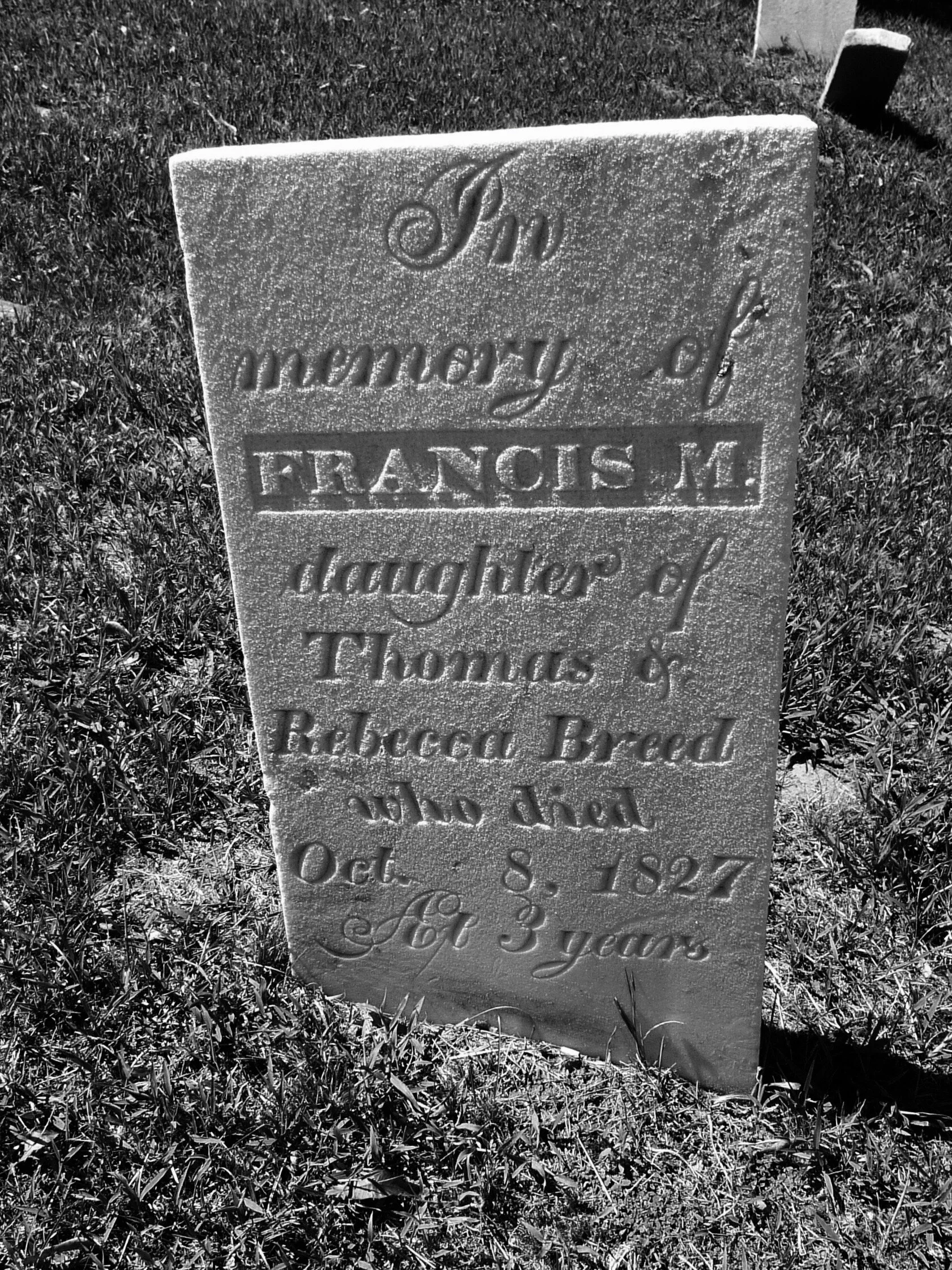

Francis Breed was three when she died, in 1827. The stone carver had a penmanship flourish.

Stand in any old New England cemetery and you’re surrounded by premature death. Living along New England's rocky shores in the 18th and 19th centuries meant a constant range of childhood diseases, some spread in pandemics, such as measles, diphtheria and smallpox, if mother and infant survived childbirth, and the other maladies and dangers that often made life brutal and short.

Within a radius of a dozen feet in this handsome necropolis just north of Stonington Borough, there are several reminders of loss in a pre-vaccine world.

Samuel and Alzayda Robinson's son William left this life at 18 months, but with no fancy inscription, just simply: “DIED’’.

Charlotte Augusta Staples, aged one year and seven days, had the same carver as William Robinson nearby, but here with this inscription:

“Happy infant early blest/

Rest in peaceful slumber rest’’

Captain Joseph Eells, born in 1768, got a 19th-Century stone. Perhaps Eells was lost at sea.

Saddest of all, Lydia Palmer was a young wife when she she died (giving birth?) at only 18. Her weeping willow, carved in porous sandstone, is eroding. The inscription here reads:

“Behold & see as you pass by,

As you are now so once was I,

As I am now so you must be,

Prepare for death & follow me.’’

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural historian and essayist. His latest book, Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter, will be published next month.