David Warsh: Putin wants to get his foes thinking

Vladimir Putin in 2018

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The first bright light on the murky situation in Ukraine shone Jan. 28, when Ukraine officials “sharply criticized” the Biden administration, according to The New York Times in its Jan. 29 edition, “for its ominous warnings of an imminent Russian attack,” saying that the U.S. was spreading unnecessary alarm.

Since those warnings have been front-page news for weeks in The Times and The Washington Post. Ukrainian President Volodynyr Zelensky implicitly rebuked the American press as well. As the lead story in The Post indignantly put it, he “ [took] aim at his most important security partners as his own military braced for a potential security attack.”

Meanwhile, Yaroslav Trofimov, The Wall Street Journal’s chief foreign-affairs correspondent, writing Jan. 27 in the paper’s news pages, identified a well-camouflaged off-ramp to the present stand-off, in the form of an agreement signed in the wake of the Russian-backed offensive in eastern Ukraine in February 2015. The so-called Minsk-2 had since remained dormant, he wrote, until recently.

Now, after a long freeze, senior Ukrainian and Russian officials are talking about implementing the Minsk-2 accords once again, with France and Germany seeing this process as a possible off-ramp that would allow Russian President Vladimir Putin a face-saving way to de-escalate.

I have had a long-standing interest in this story. In 2016, in the expectation that Hillary Clinton would be elected U.S. president, I began a small book with a view to warning about the ill consequences of the willy-nilly expansion of the NATO alliance that President Bill Clinton had begun in 1993, which was pursued, despite escalating Russian objections, by successors George W. Bush and Barack Obama. The election of Donald Trump intervened. Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years appeared in 2018.

I was relieved when Joe Biden defeated Trump, in 2020, but alarmed in 2021 when Biden installed a senior member of Mrs. Clinton’s foreign-policy team in the State Department, as undersecretary for political affairs. Seven years before, as assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, Victoria Nuland had directed U.S. policy towards Russia and Ukraine and passed out cookies to Ukrainian protestors during the anti-Russian Maidan demonstrations in February 2014. At their climax, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, a Putin ally, fled to exile in southern Russia, and, in short order, Russia seized Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula.

A couple of weeks ago, I suggested that, when it came to interpreting the situation in Ukraine, it would be wise to pay attention to a more diverse medley of voices than the chorus of administration sources uncritically amplified by The Times and The Post. David Johnson, proprietor of Johnson’s Russia List, told readers he didn’t think there would be an invasion. Neither did I. Russian and Ukrainian citizens seemed to agree; according to reports in the WSJ and the Financial Times, they were going about their business normally.

Why? Presumably because most locals understood Russian maneuvers on their borders to be a show of force, intended to affect negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow.

As for what Putin may be thinking and privately saying – his strategic aims and his tactics – I pay particular attention to Harvard historian Timothy Colton. His nuanced biography of Boris Yeltsin makes him an especially interesting interpreter of the man Yeltsin in 1999 designated his successor.

Colton, a Canadian, is a member of the Valdai Discussion Club, a Moscow-based think-tank, established in 2004 and closely linked to Putin. Its annual meetings have been patterned on those of Klaus Schwab’s better-known World Economic Forum, in Davos, Switzerland. Membership consists mainly of research scholars, East and West. A little essay by Colton surfaced 10 days ago on the club’s site, as What Does Putin’s Conservatism Seek to Conserve?

Colton observed that Putin’s personal ideas and goals, as opposed to his exercise of power as a political leader, are seldom discussed. That is not surprising, he wrote, as Putin had relatively little to say about his own convictions during his first two terms in office, aside from First Person, a book of interviews published just as he took office in 2000. That reticence diminished in his third term, Colton continued, especially now as his fourth term begins. In a speech to a Valdai conference last autumn, whose theme was “The Individual, Values, and the State,” Putin borrowed a foreign term – conservatism – and used it four times, each time with a slightly different modifier, to describe his own fundamental views. Colton wrote:

Putin noted at Valdai that he started speaking about conservativism a while back, but had doubled down on it in response not to internal Russian developments but to the fraught international situation. “Now, when the world is going through a structural crisis, reasonable conservatism as the foundation for a political course has skyrocketed in importance, precisely because of the proliferating risks and dangers and the fragility of the reality around us.”

“This conservative approach,” he stated, “is not about an ignorant traditionalism, dread of change, or a game of hold, much less about withdrawing into our own shell.” Instead, it was something positive: “It is primarily about reliance on time-tested tradition, the preservation and increase of the population, realistic assessment of oneself and others, an accurate alignment of priorities, correlation of necessity and possibility, prudent formulation of goals, and a principled rejection of extremism as a means of action.”

What of the wellsprings of Putin’s conservatism? Perhaps nothing more fundamental than the preservation of his own power. “Two decades in the Kremlin, and the prospect of years more, may incline him increasingly toward rationalizations of the status quo as principled conservatism.” An alternative explanation would emphasize life experience. The fragility that Putin was talking about at Valdai was that of the present moment, Colton wrote, but, he continued,

Putin has commented more than once on the inherent volatility of human affairs. “Often there are things that seem impossible to us,” he said in the First Person interviews, “but then all of a sudden — bang!” He gave as his illustration the event that by all accounts traumatized him more than any other — the implosion of the USSR. “That is the way it was with the Soviet Union. Who could have imagined that it would have up and collapsed? Even in your worst nightmares no one could have foretold this.” Sticking with “time-tested” formulas would suit such a temperament [Colton wrote].

What sorts of time-tested formulas might the Russian leader adopt? Colton, a player in many venues, is constrained to speak and write so carefully that it is hard for an outsider to know what with any confidence what point he was making to insiders in his recent essay. As journalist, I am not.

One time-tested formula Putin has employed frequently, to the point of habit, is a tradition I think of as having evolved in the West. This is the practice of setting out a frank public account of public-policy views. It is a rhetorical tactic set out with especial felicity by the framers of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, to the effect that “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” requires those undertaking dramatic actions to declare the causes that impel them to act. In general, this Putin has done.

There was, for instance, his frank appraisal of the situation of Russia at the Turn of the Millennium, published as one of those First Person interviews in 2000. After he failed to dissuade George Bush from invading Iraq, Putin lambasted the U.S. in 2007 in a widely publicized speech to a security conference in in Munich. In 2014, after annexing Crimea, he delivered another blistering speech, this time to the both houses of the Russian parliament. And last summer, he published a long essay asserting his conviction that Ukrainians and Russians share “the same historical and spiritual space.

What might he do if his army goes home, having made its rhetorical point without firing a shot? My hunch is that he will give another speech.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

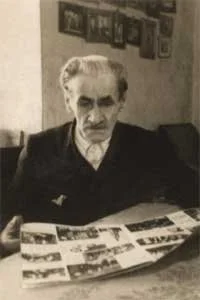

Spiridon Putin, Vladimir Putin’s paternal grandfather, a personal cook of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin