David Warsh: Bitter times —John Kerry, the Vietnam War, me and The Boston Globe

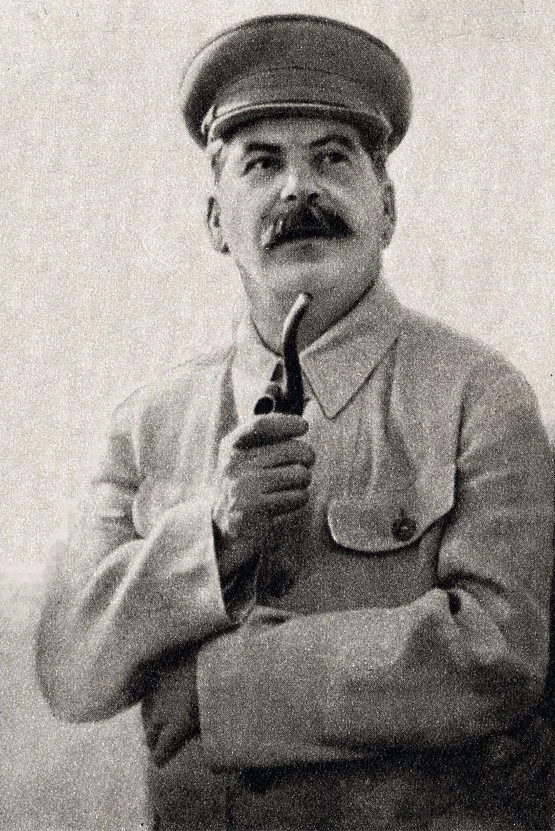

Logo of the controversial anti-Kerry Vietnam veterans group in the 2004 presidential candidate

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

What does a top newspaper editor owe his publisher? The press critic A. J. Liebling famously wrote: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Tired of arguing with a friend about the implication of that dictum, I threw up my hands a year ago and walked away. Since then, interest in the question has been rekindled. I decided to re-engage

The particular case that interests me has to do with the role of The New York Times in the 2004 presidential election. It was then that the first collision occurred between mainstream news media and crowdsourcing on the internet: The derisive Swift Boat Veterans for Truth vs. the John Kerry campaign. Did the presidency hang in the balance? There is no way of knowing. George W. Bush received 50.7 percent of the popular vote, against 48.3 percent for Kerry; in the Electoral College, the margin was slightly wider, 286 to 251.

In at least in one respect, crowdsourcing seemed to have won its contest that year. More news about dissension within the Swift Boat ranks appeared first on the Web during the second half of the year, rather than in newspapers. As Jill Abramson notes in Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts (Simon & Schuster, 2019), the newspaper business changed after that.

I followed what happened in 2004 because eight years earlier, I had become involved in what turned out to have been its quarter-final match. In 1996, Kerry, the junior U.S. senator from Massachusetts, was running for re-election to a third term against a popular two-term governor, William Weld. Kerry decisively defeated Weld, sought the Democratic vice-presidential nomination in 2000, then secured the Democratic Party’s nomination in 2004 to run against Bush.

Until 1996, Kerry was known to the national public mainly as a critic of the Vietnam War. The ‘80s, which began with the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan and Ronald Reagan’s election to his first term, had changed attitudes toward America’s experience in Vietnam. Though first elected in 1984 – on, among other things, a promise to stop U.S .atrocities in Nicaragua, – Kerry’s 1996 senatorial campaign was the first one in which he sought to tell the story of his war in Vietnam. He gave highly personal accounts of his service to Charles Sennott, of The Boston Globe, and to James Carroll, of The New Yorker, which appeared a month before the election. In reading them, I was struck by certain inconsistencies in the senator’s accounts – in particular, by the relatively short time he had spent in Vietnam.

I was then a columnist on the business pages of The Globe, writing mostly about economics and its connection to politics, but for a year (1968-69), as a second-class petty officer in the U.S. Navy, I had been a Pacific Stars and Stripes correspondent, based in Saigon, and, for a year after that, a stringer for Newsweek magazine.

After Kerry boasted of his service and disparaged Weld for not having gone to that fight, I wrote a column on Monday for Tuesday, Oct. 22, that was headlined “The war hero.” In the course of my reporting, a member of Kerry’s Swift Boat crew, who had been put in touch with me by the campaign, confided in the course of a long conversation a detail that hadn’t appeared before. A second veteran, a former Swift Boat officer-in-charge, phoned the paper to offer additional details. I requested permission to draft a follow-up column, and received it.

A year ago, I told my story about how that second column came to be written. Below, I put into the record a parallax account of the key events of that week, in the form of a November 1996 letter from former Boston Globe editor Matthew Storin to a strident critic of The Globe’s coverage of Kerry in this instance. I include the letter to which he was responding as well below. They are long and painful to read, and unless you, too, are interested in 2004, you can skip them.

I am writing all of this now for two reasons. I learned last year that having retired from the newspaper business, Marty Baron is writing a book. Collision of Power: Trump, Bezos, and The Washington Post (Flatiron) is said to be about his eight years as executive editor of The Post, beginning just after Amazon founder Jeff Bezos purchased the paper from the Graham family. That makes Baron an expert on the central topic here; all the more so since in 2011, he was considered one of the three likeliest candidates to replace executive editor Bill Keller in the top news job at The Times, according to Jill Abramson, who ultimately got the job. I am eager to see what Baron says about The Globe’s 2004 book about Kerry, so I decided to put on the table the first of the cards that I possessed.

I also want to express the conviction that the resounding success of the tactics Kerry employed in 1996 probably cost him the presidency in 2004. During the week in the fall of ‘96 that we waited for the campaign’s reply to questions raised by “The war hero” column, we accumulated several new bits and pieces of information. Had his staff kept its promises, we would have asked questions about them, but I doubt that I would have written a second column, and certainly not the second column that appeared. Probably we would have waited until after the election, perhaps long after the election, to begin to resolve the questions. Meanwhile, Kerry might have learned how to talk about the issues that would be so starkly raised in 2004.

Instead, a hastily arranged Sunday rally, as Storin’s letter makes clear, was the equivalent of an ambush. Kerry and others, including Adm. Elmo Zumwalt, Commander of Naval Forces in Vietnam when Kerry had been there, assembled from around the country and appeared in the Boston Navy Yard to fiercely denounce the second column, barely 12 hours after it appeared in print. The effects were blistering. With the election 10 days away, The Globe covered the rally and otherwise put the story aside.

I received a copy of Storin’s letter to the critic soon after the election, via interoffice mail. In the five years I remained at The Globe, I was never asked by senior editors about what I had learned. The news business was different in those days. Newspapers were still regnant, but their owners embraced differing principles and possessed different points of view. The Globe had been purchased by New York Times Co., in 1993. Under a standstill agreement, the paper was still managed by the Taylor family in 1996, as it had been for 125 years. Even then, the implications of the sale were beginning to come clear. NYT Co. president Arthur O. Sulzberger, Jr. fired Benjamin Taylor as. Globe publisher in 1999, and replaced Storin with Baron in mid-2001.

Kerry considered questions about his experiences in Vietnam, asked in the rough and tumble of the news cycle, to be illegitimate; I and my editors considered them appropriate in the circumstances. None of us, I think, would have felt any compulsion to publish that second column had the campaign kept its promises. We’ll never know. But in refusing to respond, and attacking instead, Kerry had effectively ruled the questions out of bounds.

Kerry’s success in 1996 may have bred over-confidence going forward. The next eight years produced little news on these matters. The historian Douglas Brinkley wrote his campaign biography, Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War (William Morrow, 2004). By the time it appeared, a whole new wing of the news industry had gained an audience – Rush Limbaugh, the Drudge Report, the Fox News Network, Bill O’Reilly and Andrew Breitbart.

When the same ambush tactics the Kerry campaign employed against The Globe were used against him in May 2004 by the organization calling itself Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, it was too late to disarm. Kerry toughed it out. Bluster and evasion had become a habit.

. ••

“November 6, 1996

“John M. Hurley, Jr., 78 Longfellow Road, Wellesley. MA 02181

““William 0. Taylor, Chairman; Benjamin B. Taylor, President; Matthew V. Storin, Editor: The Boston Globe

Gentlemen: ‘

“What has happened to The Boston Globe? What has happened to the proud, 124-year tradition of impeccable journalistic standards?

“David Warsh has disgraced himself. He has shamed The Boston Globe, he has stained the profession you cherish.

“I am a Vietnam veteran, a 26-year friend of John Kerry, and a 4-decade long fan of the Boston print media. (My father was a Boston news photographer for 43 years – 29 with The Boston Post, 2 freelancing, 12 with the Globe – and he instilled in his children an unyielding admiration for the Boston print media.)

“But in 40-plus years of close observation of Boston newspapers, I have never seen a more despicable, more vicious, more baseless attack than David Warsh’s columns on John Kerry.

“Without any foundation whatsoever, without a single witness contradicting events that took place 27 years ago, without a shred of physical or documentary evidence, Warsh levels the single, most vile hatchet job that I have ever seen.

“Where is Warsh’s evidence to contradict these witnesses, where is the substantiation for his vicious speculation? There is none. Not one word. He speculates about the most heinous war clime imaginable – the commission of murder in order to secure a medal – and offers nothing in support of his speculation. Not a single witness. Not a statement. Not a document. Nothing. It is simply Warsh’s own personal, vicious speculation.

“Even a ‘decorations sergeant,’ if he has an ounce of objectivity, if he has an ounce of integrity, is capable of putting this incident into the context of a firefight: incoming B-40s. enemy fire, from both shorelines, third engagement of the day. stifling heat. deafening noise. screaming, shouting, adrenaline-driven chaos. Sheer mind-numbing chaos. Kerry and his crew were trained to do one thing in order to save their lives: react, react, REACT. Lay down a base of fire, or die. It was that simple. Even a ‘decorations sergeant’ understands that. But if you have no objectivity, if you have no integrity, you don’t put the incident into context. you write of war crimes instead.

“And what of that dead VC? According to Warsh, he was Just a tourist on holiday. ‘The one thing that seemed hard to abide was a grandstander. A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’ SAY … THAT .., AGAIN. ‘A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’

“A VC soldier … in the midst of a firefight … armed with a B-40 rocket … aimed at the crew of a U.S. Navy swift boat – and Warsh sides with the dead VC. An unlucky young man, finished off for the sake of a Silver Star by a grandstander.

“Who does David Warsh think he is? What right does he have to casually, callously, with utter disregard for the facts presented to him destroy a person’s reputation. Their character. their integrity, their honor?

“And you let him do it. Twice.

“Where are your journalistic standards. Where is your outrage. Where is your moral indignation. Where is your decency. Where ls your fairness? Do you really believe that Warsh’s vicious conjecture rises to the level of fair, objective comment? Are Warsh’s columns the stuff of which you want your newspaper judged?

“John Kerry’s honor, his crew’s honor, is intact. What of the Globe’s?

“It is important to point out that Warsh’s reporting is replete with errors. Warsh engages in the vilest character assassination imaginable, and he doesn’t even get basic facts right. In any newsroom I have ever visited ‘getting the story right’ is worn like a badge of honor. Warsh didn’t even try.

“Relying solely on personal conjecture (‘What’s the ugliest possibility? ….’) and vicious innuendo (‘Tom Bellodeau (sic) says he was awarded a Bronze Star … but I have been unable to find a copy of the citation.

“Warsh proceeds to trash the honor of Kerry, his crew, and indeed every veteran who has ever been awarded a medal for bravery.

“There is not one word of substantiation in Warsh’s diatribe. There is no foundation, no witness, no evidence, no document that contradicts what has been said or written about Kerry’s war record. Yet Warsh dangles before the reader the most heinous speculation imaginable: that Kerry murdered a wounded, helpless enemy soldier in order to win a Silver Star for himself. An unspeakable crime, yet Warsh offers nothing to substantiate it. The allegation is solely Warsh’s own vicious, character-assassinating conjecture.

“And you let him publish it. Twice.

“Warsh advances his vicious speculation even though there are rock-solid statements and documents to the contrary, statements and documents that completely contradict his spurious, hate-filled conjecture:

“Belodeau told Warsh: ‘When I hit him, he went down and got up again. When Kerry hit him, he stayed down.’

“Medeiros told the Globe’s Barnicle: ‘I saw a man pop-up in front of us. He had a B-40 rocket launcher, ready to go. He got up and ran for the tree line. I saw Mr. Kerry grab an M-16 and chase the man. Mr. Kerry caught the man in a clearing in front of the tree line and he dispatched the man just as he turned to fire the rocket back at the boat…I haven’t seen or talked with Mr. Kerry since 1969, but I admired him them and I admire him now. He saved our lives.’

“Kerry’s Silver Star citation, awarded for ‘conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action,’ signed by Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, states that the enemy soldier had a B-40 rocket launcher ‘with a round in the chamber.’

“Warsh quoted Kerry (from the Carroll piece): ‘It was either going to be him or it was going to be us. It was that simple. I don’t know why it wasn’t us – I mean to this day. He had a rocket pointed right at our boat.’

“Warsh misspelled Tom Belodeau’s name 13 times.

“Warsh referred to Belodeau as the ‘rear gunner’: Belodeau was the forward gunner.

“Warsh reports that Keny was assigned to a boat ‘whose skipper had been killed’; the skipper was not killed, he was wounded, and is alive today.

“Warsh refers to ‘heavy 50 mm machine guns’: they are .50-caliber machine guns. ‘50 mm machine guns’ are laughable; a reporter with even a cursory attempt at accuracy would have caught the error instantaneously.

“Warsh asks: ‘But were there no eyewitnesses?’ There were at least three: Tom Belodeau, Mike Medeiros. John Kerry. All were quoted in the Globe. But Warsh decided that from a distance of 27 years he knew better than they what happened that day. He ignored what they said, he opted instead to write his own personal, vicious, unsubstantiated conjecture.

“When you engage in character assassination. you have an absolute obligation to ‘get it right.’ Warsh didn’t even try. Why was he in such a hurry to get his hate-filled column into the paper?

“You have always been an aggressive, but responsible newspaper. You have never, until now, stooped this low. So, how did these columns happen? How did they get into your newspaper?

“Your journalistic integrity has been trashed by David Warsh, and the editors that OK’d these columns for publication. These columns were not a close call. These columns were flagrantly out of line. 124 years of journalist integrity has been trashed. It will take you years, if not decades. to recover from the stain of these columns.

“Hang your head in shame, Boston Globe. Hang your head in deep, deep shame.

/s/ John Hurley

“P.S. to Mr. Storin:

“And what of you, Mr. Storin?

“Did Warsh act entirely on his own? Does the Globe’s policy of complete freedom to its columnists mean that no editor even questioned Warsh about the foundation of his columns? Even when Warsh’s columns are totally outside his field of expertise? Did no editor request even minimal substantiation of his vicious speculation: a witness, a document, a statement? Anything at all?

“Does the Globe’s policy of complete freedom to its columnists extend to baseless, personal character assassination? Did you and the editors that work for you fail to see a pattern of vicious, personal attacks by Warsh?

“‘… there is,” Warsh wrote, ‘a good, strong, dispassionate reason to prefer Bill Weld to John Kerry.’ Fair enough. He’s entitled to endorse whomever he wants to. But then the pattern of attacks began:

“Warsh, Oct. 15, 1996: ‘he was acquired by John Heinz’s widow in a tax-exempt position-for dollars swap.’

“Warsh, Oct. 22, 1996: ‘The one thing that seemed hard to abide was a grandstander. A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’

“Warsh, Oct. 27, 1996: ‘What’s the ugliest possibility? That behind the hootch, Kerry administered a coup de grace to the Vietnamese soldier – a practice not uncommon in those days but a war crime nevertheless, and hardly the basis for a Silver Star.’

“A recurring pattern of vicious, unsubstantiated personal attacks. Is this what constitutes fair and objective comment under the Globe’s current journalistic standards?

“The very day Mike Medeiros was quoted in the Globe saying Kerry ‘saved our lives,’ you gave Warsh additional space, and let him – without a single witness, without a single document, without a single supporting statement – viciously speculate about a war crime, for the very act that Medeiros said saved their lives. A war crime? Admiral Zumwalt, the highest ranking Naval officer in Vietnam, stated that John Kerry’s heroism that day was worthy of the Navy Cross, the second highest medal for bravery that our country awards. (But Zumwalt recommended a Silver Star instead, because he wanted to expedite the awards ceremony and boost the morale of his troops who were taking heavy casualties at the time).

“Every witness that has spoken, every document that exists. every shred of evidence that has been found states that Kerry acted selflessly, with extraordinary heroism. Yet Warsh, without foundation, without any substantiation whatsoever, conjectures about a war crime. And you print it. Is that the journalistic standard by which you want your reading public, your fellow journalists across the country, your publishers, to judge you and The Boston Globe?

“To top off this lame, pathetic performance by you and your editors, you go on television and dismiss Warsh’s columns, saying, ‘I thought in the long run it might be favorable for Kerry.’

“Vicious, unfounded character assassination ‘might be favorable’? Ludicrous, laughable, stupid, sick.

“The basic test of character, Mr. Storin – for a man or a newspaper – is to be able to say, in the face of adversity, ‘We were wrong, extremely wrong.’ “You, The Boston Globe, and David Warsh have failed that test, egregiously.’’

“November 13, 1996

“Mr. John M. Hurley, Jr., 78 Longfellow Road, Wellesley, MA 02181

“Dear Mr. Hurley:

“Your thoughtful letter was very painful to read. You made some very harsh charges, most of which I feel were not in the same context with the decision that I was faced with in allowing publication of the David Warsh column. Nearly three decades after a signal event in the career of our junior US Senator, I had a column with a seemingly new version of events and no one willing to come forward to explain it, despite our holding the column for three days. In the midst of an election campaign, to kill such a column under those circumstances was something I could not defend.

“Here is the chronology of events that led to my decision:

1. “Warsh says he has turned up this odd statement by Belodeau that does not appear to square with the previous He writes a first version of the column that lands on our desks on Wednesday. Because we are getting closer to the election, we consider publishing it on the following day, rather than waiting until the next of his regular column dates.

2. “I telephoned John Marttila, one of Kerry’s senior advisers, and urge him to have the senator talk to Warsh. I assume the discrepancy can be straightened out. John indicates that it is next to impossible to reach the senator, who is on his way to the debate in Springfield.

3. “I tell my editing colleagues Wednesday night that we must hold the column until we are able to (a.) reach Belodeau for additional clarification and (b.) reach Senator Kerry.

4. “Tom Vallely calls me Thursday morning and discusses the Warsh I tell him what Belodeau has said (or perhaps he already knew), and he says, in pretty much these exact words, “We have no problem with that. We have no problem with that/ and explains that the guy Belodeau hit got back up and appeared still able to fire his weapon. Frankly, I am relieved to hear this because it’s a plausible explanation and we can avoid even addressing the issue anew. Vallely says he will produce “his (Kerry’s) commanding officer. I got the impression that Tom would also help get Belodeau back to Warsh and possibly the senator himself, though on the latter point I may have been mistaken. I think Tom might have said earlier that the senator would not talk to Warsh. I had to leave for a journalism conference on Long Island, but at this point I am confident that the column will not be a problem.

5. “Late Friday, I ask to have the column faxed to me. I am very surprised to learn that neither Belodeau nor Kerry has offered anything to Warsh and that the officer has said he was not an eye witness. The New Yorker quote is also puzzling to me. Yet I feel that Warsh deals with the incident with some caution, offering two possibilities. It’s an effort to examine an important incident in the military career of a major public figure who has chosen for some reason — and that is fully his right — to not answer the columnist’s questions.

“From the remove of hindsight, it is now obvious that Senator Kerry chose prior to publication to use the column (of which through Vallely and others he probably had accurate knowledge) to his own advantage. Not only is that his privilege, but it appears to have been good politics. In any event, it probably would not have been possible to get Admiral. Zumwalt here between early Sunday morning and the late afternoon press conference, so that is my assumption.

“Frankly, the column probably would have disappeared without a trace otherwise. After reading it on Friday, I told our executive editor, Helen Donovan, ‘I think this is worth 1,000 votes for Kerry.’ Given your letter, you are probably incredulous at that, but I felt it humanized the senator in a way that has often not been the case in his career. Of course, I saw the negativity in it, but I thought readers would make their own judgments about the issues – as they do with all our opinion columns.

“As to an apology, I would first like to outline what the paper has done in print. We published the story of the press conference on page one Monday, including Belodeau’s explanation for his remark and his account of the battle as well as the testimony of Medeiros, whom our reporter spoke to by telephone. Obviously this piece was presented more prominently than the original column. We then published an op-ed piece by James Carroll, criticizing us in very harsh terms. It is part of our culture to publish a column such as Carroll’s just as it is to publish a column such as Warsh’s. William Safire writes a half dozen speculative columns a year that are as harsh to Bill Clinton as Warsh’s was to Senator Kerry. When was the last time you saw an op-ed piece in the Times that criticized the Times? Finally, we published a piece by our Ombudsman that, like Carroll, said the column should not have been published.

“I personally may regret that the column ran, but, given the same set of circumstances again, I would not kill the column. I have to make those decisions in the context of columns we have run in the past and might run again in the future. We were in the middle of a tough campaign, Belodeau had made a statement that seemed at odds with anything previously published, and despite waiting three days, no one had come forth on behalf of Senator Kerry to explain it. I agree that it’s a sign of character to admit when you are wrong and, in some ways, that would be easier to explain than what I am trying to say here. I believe David Warsh may address his own personal feelings in a future column and, possibly, in a conversation with Senator Kerry if that is possible.

“It pains me to read that Senator Kerry feels this was a low point in his life. I am certain of one thing: It would have been avoided if he had given a statement to Warsh as we had asked. His failure to respond — even if he wanted to call a press conference in advance — took out of my hand a major argument for changing or killing the column (though I believe Warsh would have treated the subject much differently). Your citation of the Medeiros quote is interesting. The campaign obviously chose to make Medeiros available to another columnist, rather than reply directly to Warsh. That’s another legitimate political decision by the Kerry campaign, but it didn’t help with the decision I had to make on Friday evening (deadlines are earlier for Warsh’s column than for Barnicle’s). I understand that the senator and some of his advisers felt wary of dealing with Warsh, but Tom Vallely and John Marttila knew that I had personally involved myself in the issue and could have phoned me back at any time between Thursday morning and Friday night. Though I was out of town, I was easily reachable.

“I do regret — and they are inexcusable — the relatively minor but not insignificant “inaccuracies in Warsh’s column that you cited.

“In closing, I would like to note that you are a longtime friend of Senator Kerry. I understand you may have even played a role in the campaign’s effort to deal with the Warsh column. I am neither a friend nor supporter of John Kerry nor Bill Weld. I do everything in my power, in terms of social relationships, to put myself in a position to make dispassionate decisions as a journalist. I accept that you are upset with us, but I hope you will sometime reread your letter and recognize that you made some emotional charges that were not justified.

“Sincerely

/s/ Matthew V. Storin’’

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

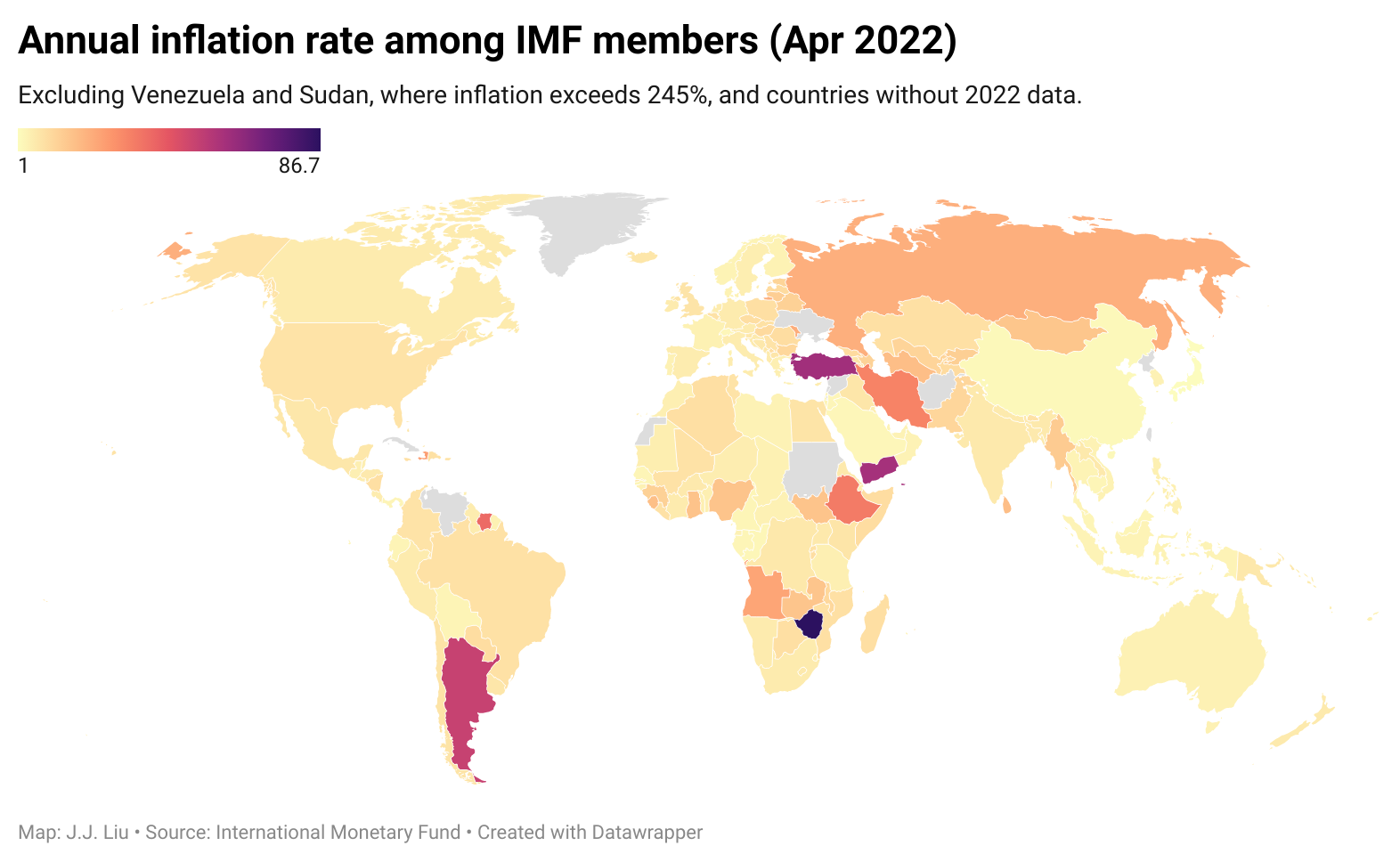

David Warsh: 'Depreciation,' 'development' and 'inflation'

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Everyone knows that the cost of living has risen significantly in the past 75 years — recently, at rates not seen since the early ‘80s. To understand a little better why this has is happening, try this simple trick: Think of rising prices as a matter of the depreciation of the dollar against the prices of goods and services, instead of “inflation.” That won’t make the experience any less disorienting than calling it by the headline term, but it will give you a better sense of how and why the problem has arisen.

What’s the difference? With “inflation,” the answer is implied by the question. The explanation is always the same: the governors of the Federal Reserve Board have been cavalier with interest rates. Too much money is chasing too few goods. “Depreciation,” on the other hand, permits you to think about events taking place in the real world that forced the Fed’s hand – events that monetarists commonly describe as “ad hoc.”

Certainly a great deal of “ad hoc” change has occurred in the real world since 1950, when a candy bar cost a nickel and a haircut could be had for $1.25. Very little of the momentum behind that history would seem to have originated with the Fed, the stringent tightening of monetary policy in 1979-’82 being the major exception.

The current episode of rapidly rising prices is associated with the governmental response to COVID; accelerated with outbreak of all-out war in Ukraine; deglobalization of supply chains; food shortages and the threat of famine; policies designed to slow climate change, and energy disruptions now said to rival the crisis of the early and mid ‘70s.

True, in the course of regulating the nation’s system of money and banking, the Fed had to react to these various afflictions. Sometimes its governors may have overreacted. Sheer monetary incompetence can have a place in the story, too: Look no farther than the central bank of Sri Lanka for an example of that.

In the main, though, dollar depreciation occurs in response to real-world problems. Severe interest-rate policy can arrest expectations of runaway prices, as in the ‘80s. But dollar depreciation occurs in response to real forces. Never in millennia has it been reversed in a currency that endured. Repeating the mantra that “‘inflation’ is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon” is just blowing hot air.

In The Cost of Living in America: A Political History of Economic Statistics 1880-2000 (Cambridge, 2009), Thomas Stapleford, of the University of Notre Dame, describe how we came to employ sophisticated price indices to measure rising prices. The construction of economic statistics makes a fascinating story, but Stapleford spends only two paragraphs on why the cost of living changes, accepted at face-value explanations of particular episodes advanced by economists: W. Stanley Jevons, in the 19th Century, and Irving Fisher, in the 20th. In each case, the economists asserted, when “the supply of money increased, its value would fall, leading to higher prices.” Hence the “inflation” of prices by an excess of money.

But what if it works the other way around? What if the “cost-push” argument is more often correct? What if the quantity of money increases because prices are rising? Every central banker knows it is not simply one or the other; it is both. But with “inflation,” you only see one side of the story – in most instances, the less important side.

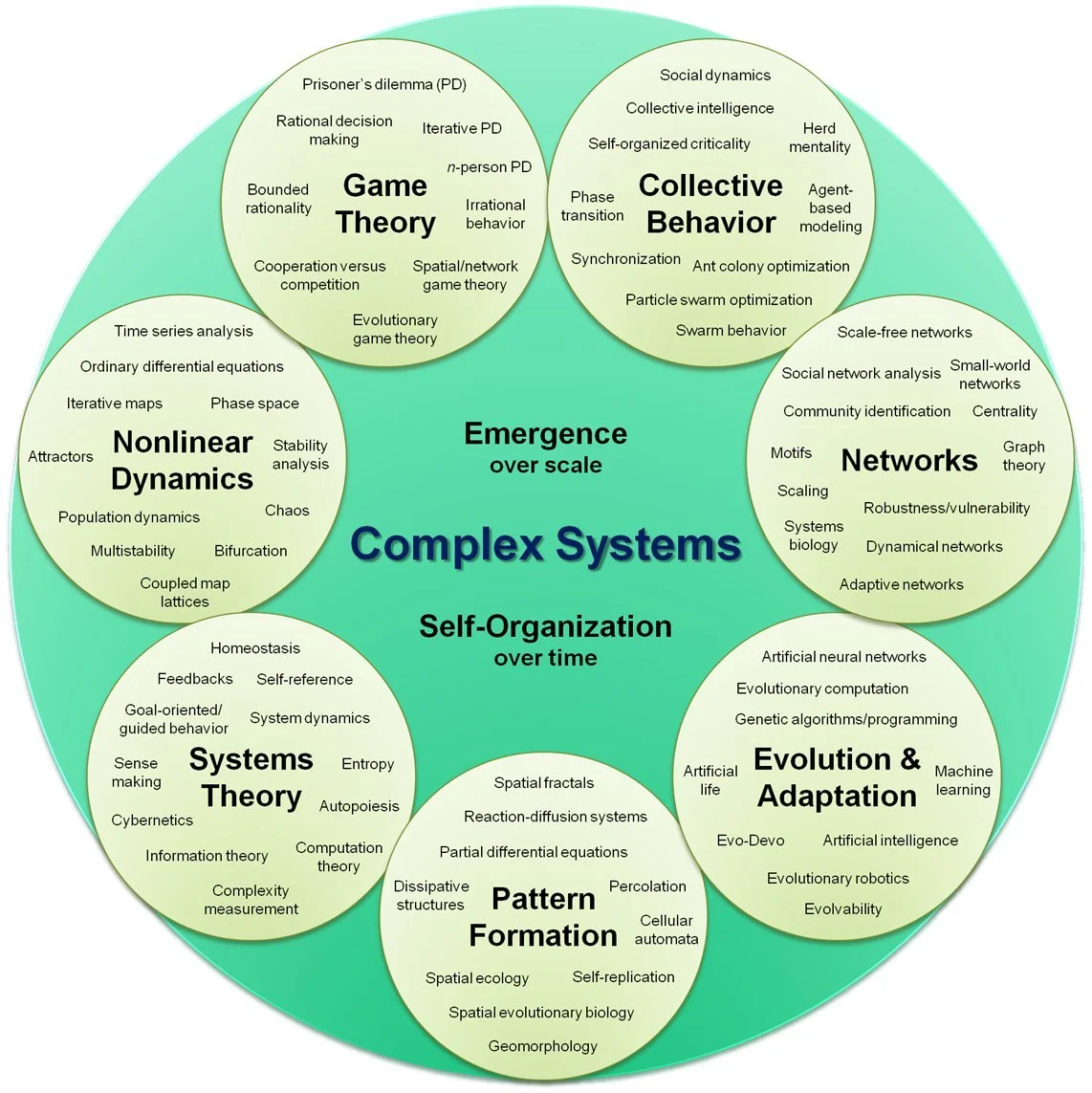

We don’t know more because there exists no conceptual scheme of sufficient generality to organize all those various “ad hoc” explanations of rising prices under one heading. Whatever intuitive appeal has existed in the term “complexity,’’ “complexity” was already well on its way to becoming a magic word, an incantation, quite devoid of meaning.

The second mistake I made was failing to notice that economists already possessed a serviceable term of their own to describe this dimension of modern life. They called it “economic development,” words as familiar and easy to use as they were lacking in precision. To give it meaning to development, as opposed to “growth,” which is a matter of inputs and output, requires only linking back to one of the most fundamental categories in all of economic theory: the division of labor.

Easier said than done! Although the role of specialization in producing material well-being is clearly spelled out in the first three chapters of An in Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith quickly moves on to the analysis of a competitive system, and this is the tradition, taken up by David Ricardo and T.R. Malthus, that has dominated economics down to the present day. I was slow to figure this out.

There! After fifty years of writing about these topics, often clumsily, my two key mistakes are acknowledged, and I have set out here all I have learned: “depreciation” and “development” (understood as the extent of the division of labor) are better language than “inflation,” not to mention (here I blush) “complexity” and “conflation” in 1984.

For a glimpse of how things might yet be different, and probably will be before long, see “One Analogy Can Hide Another: Physics and Biology in Alchian’s ‘Economic Natural Selection’”, by Clément Levallois, which ultimately appeared in 2009 in History of Political Economy. (JSTOR access required). Or tune in to Nathan Nunn, now back at the University of British Columbia. But the biological analogy at the heart of the re-launch of evolutionary economics in the years after World Wat II is too wonky for this column.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Seven Hills Park at Davis Square, Somerville. The towers in the park each represent one of the city's original hills.

David Warsh: Cambridge will be even more of a capital of economics than usual this month

MIT’s main campus, in Cambridge

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

For the first time in three years the Summer Institute of the National Bureau of Economic Research is meeting in-person in Cambridge, Mass., at least for the most part, with some on-line components as well. (In the days before Zoom, venture capitalists used to describe more expensive face-to-face gatherings as “flesh-meets,” to distinguish them from conference calls.) A parallel, pan-European policy research institution, the Centre for Economic Policy Research, now headquartered in Paris, was founded in 1983.

A substantial fraction of the NBER’s 1,700+ research affiliates, who are drawn from colleges and universities mostly in North America, and a few others scattered around the world, will troop through the Sonesta Hotel in East Cambridge over the next three weeks, along with enough colleagues and students to add up to an attendance of some 2,400 persons in all. It is the forty-fifth annual meeting of what has become, in essence, a highly decentralized Wimbledon-style tournament of applied economists, staged as a science fair, and conducted in a series of high-level seminars.

Wimbledon, in that NBER players are professionally ranked; affiliates are selected by peer-review. Decentralized, in that 49 different projects are on the docket, many of them overlapping. Science fair, in that investigators choose their own problems, and rely on agreed-upon methods to study them, while new methods themselves are the subject of a separate annual lecture. Seminars, in that presenters don’t simply read their papers they have written; they briefly describe them and then respond to discussants and badinage.

An overall program is here. A detailed day-by-day listing of sessions is here. First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund Gita Gopinath, of Harvard University, is slated to deliver the Martin Feldstein Lecture July 19 at 5:15p.m. EDT. It’s titled “Managing a Turn in the Global Financial Cycle’’.

Meanwhile, a mile down the Charles River, the Russell Sage Foundation Summer Camp in Behavioral Economies has been underway in the Marriott Hotel, some twenty-five or thirty Ph.D. candidates and post-docs studying with leading researchers, under the direction of David Laibson and Matthew Rabin, both of Harvard University.

The Summer Institute is where economic policy approaches are argued among experts. Nobel Prizes emerge mostly from summer camps. I look forward to a lot of (virtual) running-around.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicsprincipals.com. where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Three to watch in the mid-term elections

An 1846 painting by George Caleb Bingham showing a polling judge administering an oath to a voter

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

My Fourth of July resolution was to tune out stories about the possible 2024 presidential ambitions of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, and pay attention instead, at least until Nov. 8, to the Senate campaign in Ohio. Author-turned-venture capitalist J.D. Vance and Congressman Tim Ryan are running there to succeed retiring Republican Sen. Rob Portman.

Vance, 37, gained fame as author of Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis (2016). After high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and served as a public-affairs specialist in an air wing during the Iraq War. He then graduated from from Ohio State University, went on to Yale Law School and then left a corporate-law practice for a venture-capital firm in San Francisco. He returned to Ohio in 2016 to form, with partners, a venture fund of his own. Formerly an evangelical Protestant, he converted to Roman Catholicism in 2019. He opposes abortion rights.

Ryan. 49, is a 10-term congressman whose present district includes much of northeast Ohio, from Youngstown to Akron. In 2015, he explained to readers of the Akron Beacon Journal “Why I changed my thinking on abortion’’. The next year, he led an ultimately unsuccessful effort to unseat Nancy Pelosi as party leader of the House Democrats.

Might Ryan, if he wins, find a seat on that otherwise still all-but-empty bench of potential 2024 Democratic presidential candidates, at whose opposite end sits Clinton? It is plausible, if not likely. After all, former Ohio Gov. John Kasich had a shot at derailing Trump as Republican nominee in 2016. In any event, lie Vance, Ryan seems likely to remain in public life for years to come.

Jane Coaston, a journalist, is a third star rising in the mid-term elections, and probably well beyond. The New York Times hired her away from Vox last autumn to run a weekly discussion show, The Argument. Coaston grew up in suburban Cincinnati, according to Graham Vyse, of The Washington Post, the daughter of union Democrats who were “giant hippies,” before she learned to distinguish among varieties of conservative thought as editor of The Michigan Review at the University of Michigan. She gained prominence with a National Review article in 2017, “What if there is no such thing as Trumpism?” Her talk-show discussion with two leading Republican theorists after Vance’s Trump-endorsed primary victory in May was especially illuminating.

Control of the Senate will almost certainly become the dominant story of the mid-term elections. The Pennsylvania Senate race is interesting, too. To me, at least, it seems likely, that the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade will cost Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) his leadership of the Senate. This column is mostly about economics, but the investigation of preferences change is gradually becoming an important part of economics

Immigration, foreign wars, globalization and climate change: All these national issues will take a back seat in November elections, which are about leadership in particular states. They will resurface, along with women’s rights, in 2024. Harvard Historian Jill Lepore wrote a couple years ago that America, like any other nation-state, requires a “national story.” She was right. Voters write it, election by election.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: The far right's successful fifty-year campaign to pack the Supreme Court

Better when empty? The interior of the U.S. Supreme Court.

— Photo Phil Roeder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the summer of 2005. George W. Bush had been re-elected president the autumn before. He possessed political capital, he exulted, and intended to use it. His inaugural address implicitly defended his invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and, without mentioning his embrace of NATO expansion, went further still: “[I]t is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

A popular uprising in Lebanon soon boiled over, was dubbed “the Cedar Revolution,” Syria agreed to end its thirty-year occupation of southern portion of the country, and Newsweek asked, on its cover, “Was Bush Right?”

But the war in Iraq remained bogged down. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice seemed to replace Vice President Dick Cheney as Bush’s closest foreign-policy adviser. The president’s major domestic initiative, a plan to privatize the Social Security System, on which Bush had campaigned since 1978, was abandoned. And in August, Hurricane Katrina flooded and flattened New Orleans.

Bush focused on the Supreme Court.

Sandra Day O’Connor announced her retirement a few months before. Eager to nominate the nation’s first Hispanic Supreme Court justice, Bush’s first choice was his friend and former White House counsel, Atty. Gen. Alberto Gonzales. Objections to his candidacy were raised, from anti-abortion conservatives in particular. So in July Bush nominated federal Appeals Court Judge John Roberts instead.

Within weeks, Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, after a lengthy battle with throat cancer. Bush re-nominated Roberts, this time to replace the chief, and to succeed O’Connor, he nominated another old friend, Harriet Miers, a corporate lawyer from Dallas, who had replaced Gonzalez as White House counsel. She was widely criticized for lack of judicial experience.

So, despite his determination to nominate a woman, Bush chose Samuel Alito instead.

In the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama defeated John McCain. The next April, David Souter announced his retirement from the high court and Obama nominated federal Appeals Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor to succeed him. She was confirmed in August. Associate Justice John Paul Stevens retired the year after that, and though Obama was offered bipartisan support for the candidacy of federal prosecutor Merrick Garland, he nominated former Solicitor General Elena Kagan instead.

After Associate Justice Antonin Scalia died unexpectedly, in February 2016, Obama finally sent Garland’s name to the Senate to succeed Scalia, but even with seven months remaining before the November election, it was too late. Senate Majority Leader Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) refused to act on the nomination, and when Donald Trump was elected, it expired. During his term, Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett to replace Scalia, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy. McConnell got all three confirmed by the Senate.

It is not easy to pack the Supreme Court, but, working diligently, over a period of fifty years, a coalition of conservative lawyers, evangelical Christians and Catholic activists, had finally succeeded.

I was reminded of all this when I took down from the shelf The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: the Battle for the Control of the Law (Princeton, 2008), by Steven Teles, of Johns Hopkins University. Of particular salience was the early chapter on “The Rise of the Liberal Legal Network,” in which Teles describes as the conjunction of the Supreme Court led by Earl Warren and the development of an extensive supportive structure in law schools during the Rights Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s.

After that, this splendid book describes nearly everything you need to understand about the counter-mobilization that developed in the 1970s and 1980s: the advent of conservative public interest law in the early 1970s (and the early mistakes from which its institutions learned); the origins of the law and economics movement and its institutionalization by Henry Manne; the counter-networking since 1982 of the Federalist Society. There is a lot of history to imbibe in order to understand how the movement .achieved its most cherished goal last week.

On the other hand, if you want a glimpse of where the intermingling of law and economics is headed, read Republic of Beliefs: A New Approach to Law and Economics (Princeton, 2018), by Kaushik Basu, of Cornell University. Basu is a development economist, former chief economist of the World Bank (as were Paul Romer, Joseph Stiglitz and Anne Krueger), and, like them, a theorist; in his case, a student and collaborator of Amartya Sen and Anthony Atkinson. Basu expects focal points, a concept derived from game theory to play a central role in rethinking the relationship between economics and law. (Better, perhaps, to call it the study of interactive decision-making.)

What’s a focal point? You know one when you see one: shared manifestations of a psychological capacity, prevalent among humans, especially those who share common cultural backgrounds, which enables individuals to guess what others are likely to do, when faced with the problem of choosing from one among several possible options. A classic example? The decision whether to drive on the left or the right side of the road.

But that’s story for another day; a project for the next fifty years.

Meanwhile, if you are simply looking for the damaged but still-healthy roots of the mainstream Republican Party, the place to start is with Chief Justice Roberts’s opinion in the cases last week, in which he dissented from the “relentless freedom from doubt” displayed by his colleagues in their majority decisions last week:

The Court’s decision to overrule Roe and Casey {abortion cases} is a serious jolt to the legal system – regardless of how you view those cases. A narrower decision rejecting the misguided viability line would be markedly less unsettling, and nothing more is needed to decide this case.

George W. Bush’s original two preferences for the high court– Gonzales and Miers – surely would have concurred, had they been nominated and confirmed as associate justices. Roberts, it seems to me, had become the de facto leader of the old version of the Republican Party, U.S. Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyoming) its floor leader in Congress. If you want to know what will happen next, bide your time until autumn and carefully sift through the mid-term election results. Then fasten your seat belts for 2024.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Putin, Czar Peter and RealLifeLore

Portrait of Peter the Great, possibly by J.M. Nattier, in the Hermitage Museum, in St. Petersburg, named, of course, after that czar.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is becoming clear to dispassionate observers that, after surprising successes in its defense of Kyiv, Ukraine is losing hope that its troops can reverse gains that Russia has made in the east of the nation. A three-correspondent team yesterday put it this way in The Washington Post:

“[T]he overall trajectory of the war has unmistakably shifted away from one of unexpectedly dismal Russian failures and tilted in favor of Russia as the demonstrably stronger force.’’

In a speech June 9 to Russian entrepreneurs in St, Petersburg, marking the 350th anniversary of the birth of Czar Peter the Great, Russian President Vladimir Putin compared his invasion of Ukraine to Peter’s Great Northern War. That twenty-one-year-long series of campaigns, little remembered outside the Baltic nations, Russia, and Ukraine, began when Peter recruited Denmark and Norway as allies to test the newly crowned fifteen-year-old King of Sweden, Charles XII (sometimes called Karl XII).

Charles’s army defeated Russian forces three times its size at Narva, in 1700, and for a time Peter retreated, and began construction of St. Petersburg in 1703. But in 1709, as the over-confident Swedish king marched his army towards Moscow, via Ukraine, Peter’s forces crushed the Swedes in the battle of Poltava, effectively ending the short-lived Swedish Empire, and, as Peter the Great declared, laying the final stone in the foundations of St Petersburg and the Russian Empire. In the decade to come, Peter took possession of much of Finland and the northeastern shores of the Baltic.

“What was [Peter] doing?” Putin asked his audience Thursday, according to the Associated Press. “Taking back and reinforcing. That’s what he did. And it looks like it fell on us to take back and reinforce as well.”

Peter’s war in the Baltic was about gaining access to Europe. Putin’s war in Ukraine is about retaining access to European energy markets. It has been clear all along that the Russian invasion was about the possession of oil and gas resources and their transport. But the details are hard to explain.

My own path to the story followed the work of Marshal Goldman, of Wellesley College and Harvard Russian Research Center, who narrated Russian history after 1972 in a series of lucid books, culminating in Petrostate: Putin, Power and the New Russia (2008). But Goldman died in 2017. That left the field to Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy, both of the Brookings Institution, authors of The Siberian Curse: How Communist Planners Left Russia Out in the Cold, and Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin. Hill became well-known as an adviser to President Trump at the end of his term. Last week Gideon Rachman, chief foreign-affairs commentator for the Financial Times, interviewed historian Daniel Yergin to good effect in an FT podcast (s subscription may be required) .

But it turns out that the best forty minutes you can spend on the war, that is, if you have forty minutes to spend, is Russia’s Catastrophic Oil & Gas Problem, a new episode of a strange new independently produced series called RealLifeLore. Production values are striking. So is the relative lack of spin. Only the narrator’s forceful delivery wears thin, though his pronunciation of place names seems impeccable. . .

The provenance of the program itself is somewhat unclear. The YouTube link came to me from a trusted old friend; she got it from Illinois Rep. Bill Foster, the only nuclear physicist currently serving in Congress.

CuriosityStream, which carries the RealLifeLore series, is an American media company and subscription video streaming service that offers documentary programming including films, series, and TV shows. It was launched in 2015 by the founder of the Discovery Channel, John S. Hendricks. RealLifeLores’s producer, Sam Denby, is an entrepreneur best known for creating,via Wendover Productions, several edutainment YouTube channels, including Half as Interesting; Extremities; and Jet Lag, The Game. I look forward to learning more about Denby as Wikipedia goes to work and streaming networks and newspapers tune in.

I don’t know what more to say except to recommend that you watch it. It skews slightly optimistic towards the end. The Great Northern War doesn’t come into it. That’s my department, as is the is the opportunity to occasionally marvel at the yeastiness of the enterprise economy of the West, not “free” exactly, but far less clumsily guided than the system that Vladimir Putin is trying to control.

The moral of the story: Putin’s war aims are grimly realistic. Those of NATO in support of Ukraine are not. The invasion was wrong, and probably a colossal mistake, even if Russia winds up taking possession of some or all of its neighbor. Putin’s “special military operation” in the 21st Century is the opposite of Peter’s Great Northern War in the early 18th Century. Russia will suffer for decades for his folly.

xxx

Dale W. Jorgenson, of Harvard University, died June 8 in Cambridge, Mass., of complications arising from long-lasting Corona virus infection. He was 89. An excellent Wall Street Journal obituary is here.

Awarded the John Bates Clark Medal in 1971, Jorgenson was among the founders of modern growth accounting, a major force in the rejuvenation of Harvard’s Department of Economics, and, as John Fernald put it in a recently-prepared intellectual biography, attentive, supportive, warm, and kind, beneath an unfailing veneer of formality.

A memorial service is planned for the autumn.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Of financial revolutions

The Prince of Orange landing at Torbay, England, in the Glorious Revolution that overthrew James II and installed the Prince of Orange, a Dutchman, as William III.

— Painting by Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Many people at least a little about the history of the scientific revolutions of the 16th and 17th centuries; the industrial revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries; and the democratic revolutions of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Very few are familiar with the major details of the financial revolution of the early 18th Century, which began with the reforms of England’s “Glorious revolution” of 1688. In the course of the next sixty years, these developments brought into existence the modern military-industrial complex.

This relative obscurity of these long-ago events is not surprising, for, as best I can tell, the term had no currency before Peter G.M Dickson, in 1967, published The Financial Revolution in England: A Study of the Development of Public Credit, 1688-1756. Until then, the power to spend public money was colloquially described as “the control of the purse.”

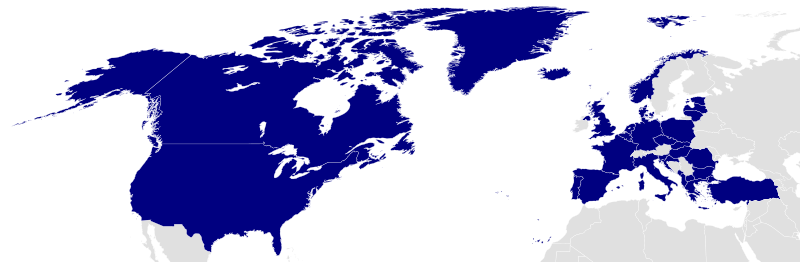

It is, however, something of a shame, since what we now call “the national debt” these days is the engine that powers military interventions around the world, from the misadventures of the George W, Bush administrations forays in Afghanistan and Iraq to Vladimir Putin’s quagmire plunge in Ukraine. You can’t fathom those periodic $60 billion appropriations bills without knowing something about the enormous multinational purse that supports NATO.

Instead, our understanding of these matters depends on combinations of vignettes and modern analysis, a sauce that often doesn’t come together.

Among vignettes, an especially appealing recent example is Ways and Means: Lincoln and his Cabinet and the Financing of the Civil War, by social historian Roger Lowenstein. It relates how Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, Lincoln’s defeated presidential rival, turned the tide of war against the South on the financial front, “levying taxes and marketing bonds, while desperately batting inflation.” A more encompassing account of government bond markets was related twenty-five years ago and updated in 2010 in Hamilton’s Blessing: The Extraordinary Life and Times of Our National Debt, by John Steele Gordon.

A welcome addition among analytics In Defense of Public Debt, by Barry Eichengreen, Asmaa El-Ganainy, Rui Esteves, and Kris James Michener (2021), a hard-headed survey of debt in the service of the state and what’s known about the limits of borrowing. The wind has largely gone out of the sails of the fad called “modern monetary theory,” thanks to books like this, and the papers cited herein. And the book synthesizes a good deal of valuable history. But the topical treatment of the issues is unlikely to make an impression on the broad public mind. That take a lifetime of research in the manner of Dickson, or, in the case of the cadre of researchers working over insights derived from a famous 1989 article about the origins of modern democracy, by Douglass North and Barry Weingast.

Thus the lack of understanding is of the financial revolution is to some degree the story of a lost book. Dickson died last year, having spent sixty years as a Founding Fellow of St. Catherine’s College, Oxford University. He revised his English Financial Revolution book in 1993, but that second edition is out of print. Even the library copy of the original was missing when I arrived yesterday. You can get some idea of the scope of the problem from its table of contents — and why the story of government bond markets is a hard tale to tell.

The Financial Revolution — 2. The Contemporary Debate — II. Government Long-Term Borrowing — 3. The Earliest Phase of the National Debt 1688-1714 — 4. Problems of Administration and Reform 1693-1719 — 5. The South Sea Bubble (I) — 6. The South Sea Bubble (II) — 7. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 8. Financial Relief and Reconstruction 1720-1730 — 9. The National Debt under Walpole – 10. War and Peace 1739-1755 — 11. Public Creditors in England and Abroad– 12. Public Creditors Abroad – 12. Government Short-term Borrowing — 13. Borrowing by Exchequer Tallies — 14. Borrowing by Exchequer Bills — 15. Departmental Credit — 16. The Bonds of the Monied Companies — 17. The Ownership of Short-dated Securities and the Market in Securities — 18. The Turnover of Securities — 19. The Rate of Interest in Theory and Practice — 20. The Origins of the Stock Exchange

A parallel history of events in France adds dimensionality to the story. French Finances, 1770-1795; From Business to Bureaucracy (1970), by John F. Bosher, describes role of the French Revolution in transforming a thoroughly corrupt system of government finance into a less venal and more efficient system. In A Financial History of Western Europe (1993), Charles P. Kindleberger, who assigned the two books in courses he taught in 1979 and 1980, wrote, “Note that the financial revolution of England preceded that of France by a century, and that the view that British military success owed to her financial capacity is matched by the statement that financial incompetence of the French monarchy was the main reason for its ultimate collapse.”

The good news is that not one but two top-flight economic historians are once again working on telling the story of the revolution charted by Dickson fifty years ago. Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution 1688-1720, by Carl Wennerlind, of Barnard College, at Columbia, was under-appreciated when it appeared ten years ago. The author bent over backwards to avoid triumphalism by incorporating, as the financial revolution’s first great success, the story of Britain’s entry into the Atlantic slave trade – the usually glossed-over precipitant and still-less-remembered outcome of the South Sea Bubble.

Anne L. Murphy, of the University of Portsmouth, who spent twelve years working trading interest-rate and foreign-exchange derivatives in the City of London, re-tooled as a historian and published The Origins of English Financial Markets: Investment and Speculation before the South Sea Bubble in 2009. The book won the Economic History Society’s best monograph prize the next year. She is preparing to publish Virtuous Banking: a day in the life of the late eighteenth-century Bank of England.

Meanwhile, Wennerlind’s new book, A Philosopher’s Economist: Hume and the Rise of Capitalism, co-authored with Margaret Schabas, of the University of British Columbia, appears next month. The financial revolution of the eighteenth century is with us every day. The extent and significance of its evolution has yet to be fully spelled out to a 21st Century audience.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: South Sea Bubble — Economists, historians and journalists -- who has the last word?

Hogarthian image of the South Sea Bubble from the mid-19th Century, by Edward Matthew Ward.

DURHAM, N.C.

I’m participating in a conference here on one of its favorite topics – the relationship between professional economics and the news business. A few durable themes stand out. One is the susceptibility of market systems to manias, panics, and crashes.

The most interesting draft paper presented here goes back to the beginnings of modern times to ask, what did London newspapers know, and when did they know it, about the disaster we know today as the South Sea Bubble.

In “British Lions Crouched to a Nest of Owls,” Carl Wennerlind, of Columbia University’s Barnard College, describes the episode as “one of the most iconic economic events in history.” In the summer of 1720, shares in the South Seas Company were offered to the public at £170. The stock’s price rose to £1,000, before falling to £200 by September, with ruinous effects on the hopes and dreams of families of London emerging upper middle class. A hundred other lesser public offerings had amplified the boom and turned it into a high fever.

What we remember is the outpouring of scorn and blame dished out after the fever broke – in printed ballads, poems, satirical plays, novels and pamphlets, including works by Jonathan Swift and Daniel Dafoe.

Usually overlooked is the expectation that puffed up the mania – Britain’s entry into new markets for slaves. Realistically speaking, the formation of the South Sea Company was motivated out of practical concerns with the expensive financing. But what remains is the memory of the Crash.

In 2001, historian Julian Hoppit published “The Myths of the South Sea Bubble.” He argued that the effects of the incident had been overblown in those famous accounts in its aftermath. Hoppit identified three commonplace views that showed types of misunderstandings to which the Bubble had been prey.

[F]irst, that investors came from far and wide, but blindly left behind all reason and prudence, skepticism and caution; second, that it produced considerable social mobility by enriching any and impoverishing more still; and, third, that its collapse led to widespread and profound economic dislocation.

Wetterlind himself is author of a well-received book in which the Bubble plays a part: Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution 1620-1720 (Harvard, 2011). His curiosity reawakened, Wetterlind did something no one had done before. He read everything written in London newspapers about financial markets during that fateful year.

His conclusion: newspapers had been slow to share the growing exuberance, but quick to assign blame when it went awry, “Courageous and noble English people had fallen victim to the dark and sinister forces of stock-jobbers,” is how he rephrased the headline that gave him his title. The lead-up to the Bubble he found reported in January-April 1720; the Bubble itself began to inflate in May as the public learned that there would be more shares to be had, and reached its highest level by the end of June. It burst in Auges and continued to deflate throughout September. In October, the aftermath began.

The day-to-day newspaper time-line that Wetterlind produced seemed valuable to me, given the significance that has been assigned to the Bubble for centuries. But a second dividend came clear when I read over Hoppit’s account. The narrative timeline of inside information he assembled from archival sources, seemed top recede information available to newspaper readers by a month or two.

This Robert Harley, the Earl of Oxford, heard from his daughter by letter in March, “The town is write mad about the South Sea, some losers, many great gainers, one can hear nothing else talked of.” A month later, his son reported, “The madness of stock-jobbing is inconceivable. The wildness is beyond my thought” And a month later,” as newspapers began to recognize the Bubble’s beginning, .“The demon of stock-jobbing is the genius of this place. This fills all hearts, tongues, and thoughts. , and nothing is so like Bedlam as the present humour which has seized all parties: Whigs, Tories, Jacobites, Papists and all sects.”

Evidence, of more were needed, that newspapers often lag well behind the insiders in whatever story they are seeking to cover, but well ahead of those who lack newspapers to read. The, as now, journalists wrote the first draft of history. Economists then interpret the available data and fit their findings into pre-existing analytic frameworks

Bu historians, in this case economic historians as well as historians of economics, have the last word in assessing significance. The conference was a promising beginning to a long-range reconnaissance patrol.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: What Putin had hoped in assaulting Ukraine

St. Andrew Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Boston.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Two days into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the dispatch from Russia’s state-owned news service seemed to reflect Vladimir Putin’s innermost reasoning.

A new world is coming into being before our very eyes. Russia’s military operation has opened a new epoch…. Russia is recovering its unity – the tragedy of 1991, this horrendous catastrophe in our history, its unnatural caesura, has been overcome. Yes, at a great price, yes through the tragic events of what amounts to a civil war, because now for the time being brothers are shooting one another… but Ukraine as anti-Russia will no longer exist.

Instead, the Novosti account continued, the Great Russians, the Belarusians and the Little Russians (Ukrainians) would come together as a whole – a reconstituted Russian Empire. Putin had undertaken the “historic responsibility” of reunification upon himself “rather than leaving the Ukrainian question to future generations.”

The pronouncement was quickly taken down, according to Jonathan Haslam, Kennan Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, N.J., describing Putin’s Premature Victory Roll in early March. It wasn’t just the over-optimism that rendered it embarrassing. It was too transparent. The goal of reunification superseded Putin’s usual complaint about the threat to Russia posed by NATO expansion.

I was broadly sympathetic to Putin after 1999, when he published his essay on Russia in the Twenty-First Century as an appendix to his First Person interview in 2000, upon taking office. I overlooked the Second Chechen War. I began paying attention after he criticized the U.S. for its invasion of Iraq in a speech in Munich, in 2007. Even after Putin’s seizure of the Crimean Peninsula, in 2014, he seemed to be within his rights, though barely. Russia had a historic claim on the peninsula on which its Black Sea naval base in Sebastopol in situated, I reasoned.

No more. Last week I re-read Putin’s article from last August, On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians. Then I read When history is weaponized for war, historian Simon Schama’s scathing criticism of it, When the Pope sought to give Putin an excuse for his invasion, in an interview with an Italian newspaper earlier this month, asserting that NATO had been “barking at Russia’s door,” it rang hollow. Nobody is talking about a Morgenthau Plan for Russia after the war in Ukraine, but nobody is talking about a Marshall Plan, either. It has options – a stronger alliance with India? But regaining its reputation in Europe looks harder than ever.

NATO’s long-term strategy of “leaning-in” seems to have worked. Putin may or may not have cancer, as a report suggested yesterday in The Times of London, but something has seriously wrong gone wrong with the man. Haslam cites Shakespeare. Putin has waged a war he cannot win. He is cementing in place the fence around him of which he complained.

Consider that his war on Ukraine has persuaded Finland and Sweden to seek to join NATO.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran. He’s the author of, among other books, Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Enlargement) after Twenty-Five Years.

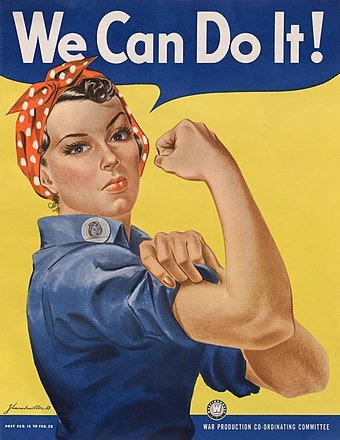

David Warsh: The expansion of women’s economic freedom that helped lead to Roe v. Wade

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The circumstances that gave rise to the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, to establish physicians’ right to counsel the possibility of medical abortion, are not easy to recall. There was so much turmoil on the surface of things fifty years ago – Vietnam, Watergate, Richard Nixon’s landslide re-election. In retrospect, one skein of developments stands out as more momentous than the rest: the rapidly changing opportunities available to American women.

For that reason, there is no better place to start than with Harvard economist Claudia Goldin’s Career and Family: Women’s Century-long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021). A distinguished economic historian, Goldin organized her account around the experiences of five roughly defined generations of college-educated American women since the beginning of the 20th Century. Each cohort merits a chapter.

The revolution, Goldin finds, was a technological one: the advent in the Sixties of dependable methods of birth control – the Pill, the IUD and the diaphragm. Women began re-entering the workforce on new terms. After explicating the traditional logic of early marriage – perhaps timeless, evolutionarily speaking – Goldin writes:

Armed with the new secret ingredient, the recipe for success became, “Put marriage aside for now. Add gobs of higher education. Blend with career. Let rise for a decade, and live tour life fully. Fold family in later.” Once this happiness formula was adopted by large numbers of women, the age at first marriage increased, even for college women who did not take the Pill. That reduced the potential cost of long-run cost of marriage delay for any one woman.

With that, the 7-2 majority decision in Roe v. Wade was almost an afterthought. The Supreme Court doesn’t just follow the election returns; they have families, and read the newspapers as well. .

Since 1982, the Federalist Society, conservative legal representatives of that year’s “Silent Majority,” have been working to reverse the decision by fundamentally transforming the judicial interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. You can read historian David Garrow’s triumphant summary of these “originalist” and “textualist” movements here.

Meanwhile, a May 7 Boston Globe story (subscription required) about Sir Matthew Hale, the 17th Century jurist whom Associate Justice Samuel Alito cited more than a dozen times in his 98-page draft opinion, makes equally interesting reading. Reporter Deanna Pan may have surfaced another plausible reason that the draft was leaked.

If experience is any guide, the next twenty-five years will see an avalanche of work on the other side of the argument, produced by legal scholars, historians, economists and other social scientists. Quite apart from whatever the election returns in the coming years might be, a movement to explain changing values and preferences has been underway in economics for years. New views on the joint evolution of institutions and cultures are entering the mainstream.

The Supreme Court is one of those institutions – central banks are another – to which democratic societies have delegated decision-making powers in the hope that in difficult times they will make more far-sighted policy choices than those of the current majority.

The court decided Roe v, Wade correctly in 1973. In all likelihood, it will sooner or later rise to the occasion again, In the meantime, stay calm; plan ahead, and cope with consequences if the expected reversal eventuates. Don’t throw the Supreme Court baby out with the bathwater.

David Warsh a veteran reporter, columnist and economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

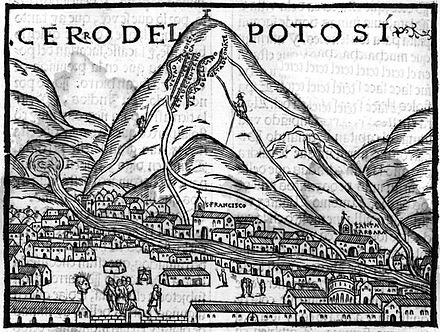

David Warsh: Money follows development and vice versa

Cerro Rico del Potosi, the first European image, in 1553, of a silver-ore-rich mountain in what became Bolivia. It was heavily exploited by Spain.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A candy bar that cost a nickel in 1950 today costs $1.25 or so, depending on where you buy it. That, in a paper wrapper, is the price revolution of the 20th Century. Why did it happen? The answer usually given is that the quantity of money increased – too much paper money chasing too few candy bars.

A more satisfying explanation, casual though it may be, is to recognize that the global economy has grown considerably more complex since 1950, and the system of money, banking, and credit more complex along with it. The price of the candy bar wasn’t going to return to its previous level, no matter what the Fed or the candy-manufacturers did.

I’ve believed this for forty years, since writing The Idea of Economic Complexity, which appeared in 1984. While nothing has happened to change my mind, it has been interesting, at least to me, to have spent a few Saturdays thinking about what I have learned since then. Let me sum it up with a last few words of explanation, before putting it away.

At the moment, the jolt to increased economic complexity has to do with Russia’s war on Ukraine, the post-Cold War expansion of the NATO alliance and long-lasting disruptions of world trade stemming from the COVID pandemic. These “cost-push” factors are more fundamental to today’s rising prices, I believe, than whatever misjudgments that monetary authorities have made in responding to them. But arguing about recent events is the wrong way to develop views about phenomena as mysterious as the formation of money prices. For that, long-term developments serve best.

The price revolution of the 16th Century is the best example in the last thousand years of a lengthy, unreversed increase in money prices of everyday things. Its magnitude was modest by current standards; but then, so were monetary systems in those days. Between 1501 and 1650, prices of everyday goods across Europe rose six-fold before leveling off and remaining more or less stable on a new level for the next hundred years.

Practically from the beginning, scholars have argued about whether the discovery of the riches of Spanish America initiated the price revolution, or whether the voyages of discovery were undertaken in response to European events already underway. Jehan Cherruyt de Malenstroit blamed rising prices on shortages of precious metals and the extravagance of kings. In a widely read rejoinder, philosophe Jean Bodin, in 1568, ascribed rising prices to the influence of the treasure of The Americas – such was the beginning of what we have called ever since the quantity theory of money.

Economic historians were still arguing about these matters four centuries later. In American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, Earl Hamilton wrote, in 1934, that an “extremely close correlation” between growth in the volume of gold and silver imports from the New World and commodity prices in Spain “demonstrated beyond question” that the abundance of mines in New Spain was “the principal cause” of the price revolution. In Economic Development and the Price Level, in 1962, Geoffrey Maynard argued the opposite: that money generally adjusts to trade, rather than trade to money. In very different formats, the argument continues today.

“Development” is a bland word with which to describe the difference between the world economy in the time of Columbus and the world today. Economic philosopher David Ellerman has suggested that diversity describes the key difference, grounding his description in information theory; I proposed complexity in that 1984 book. But what is it that has become more diverse or complex? Not until I read “Increasing Returns an Economic Progress” (1928), by Allyn Young, did it occur to me that the growing complexity I had been thinking about were increases, of one sort or another, in the division of labor.

And there I left the subject behind. I was working for a magazine when I began writing about price history, complexity and plenitude, an exotic argument about the tacit assumptions of quantity theory of money, gleaned from reading Arthur O. Lovejoy’s The Great Chain of Being (1936). Magazines are lightweight vessels, quick to maneuver in pursuit of advantage, quick to move on. There was no way I could continue to write about economics.

Fortunately, I made my way to a serious newspaper. I finished the book I had begun, and soon put complexity behind me – until this spring, when I briefly took it out to re-examine it. Meanwhile, I had become an economic journalist, following the profession. I stumble on developments in growth theory, and these, too, eventually became a book, Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (2006).

So what have I learned? That journalism is about knowing, whereas economics is about proving. A great deal more truth can become known than can be proved, as physicist Richard Feynman once said. Complexity of the division of labor is still out there. Economists will get to it someday. See, for example, Hendrick Houthakker, “Economics and Biology: Specialization and Speciation” (1955). In the meantime, there are other important stories, happening now.

In case you are feeling unsatisfied, though, remember that five-cent candy bar. Are you comfortable with the too-much-money-chasing-too-few-goods story? Do you believe that the Fed could have prevented the rise in its price? And if wasn’t “inflation,” then what was it? The depreciation of money, relative to goods?

As with the 16th Century voyages of discovery, money follows development and development follows money. If you have only the quantity theory of money to rely on, you don’t know what is going on.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Trying to figure out how to measure ‘inflation’

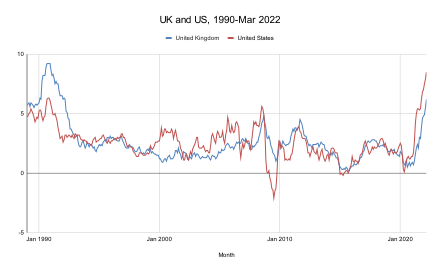

British and U.S. monthly inflation rates from January 1990 to February 2022.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

President Biden calls it Putin’s inflation. Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell says the problem began with the pandemic. Harvard University economist Lawrence Summers blames the Fed. Who’s right? Some 250 years of interplay between the science of pneumatics and its technological applications were the background against which economist Irving Fisher, in 1928, expanded the modern usage of the term “inflation” to mean something more than rising prices. Fisher is not a bad place to begin to look for an answer.

Arguments about whether or not such a thing as a vacuum can exist; quicksilver (meaning mercury); barometers; j-tubes; air pumps; valves, cylinders, and plungers; hot air balloons; footballs; the discovery of inert gases (starting with helium); the manufacture of incandescent light bulbs; pressure cookers; inflatable tires – these topics or objects became familiar before Fisher took advantage of relationships among pressure, volume, and temperature of gases, itself by then vaguely understood, in order to attach a new meaning to an old word.

“Anyone… reading [The Money Illusion] (Adelphi, 1928) by Fisher, or other books on monetary affairs published in this period, may have some difficulty with terminology” wrote Fisher’s biographer, Robert Loring Allen, many years after the fact. “For more than a generation, the words ‘inflation’ or ‘deflation’ [had] usually meant increasing or decreasing prices.” But in The Money Illusion. Allen wrote, Fisher coined new meanings: “the words inflation and deflation refer to the money supply, not to prices. Money inflates and in consequence prices rise and a deflation in the money supply causes falling prices.”

It was the first and only book about the subject that Fisher, a prominent Yale University professor and tireless reformer, would write for the general public. He was at pains to explain what he meant.