Scott Taylor: The mystic and the mathematician

The Babylonian mathematical tablet, dated to 1800 B.C.

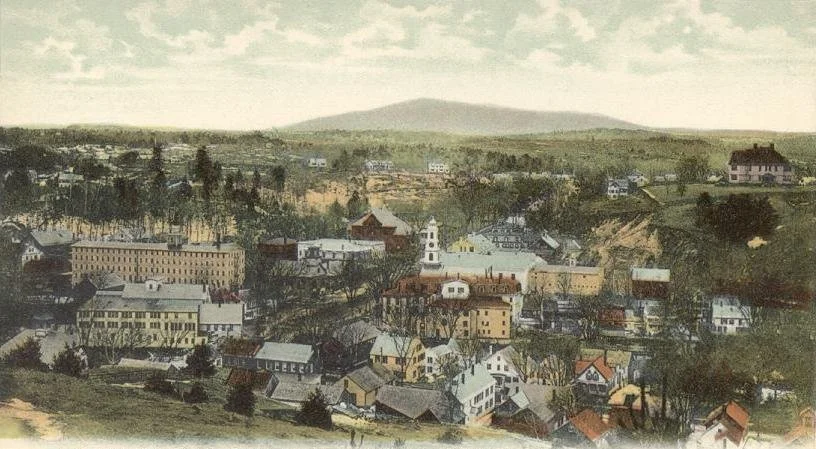

‘Waterville, Maine

Like most mathematicians, I hear confessions from complete strangers: the inevitable “I was always bad at math.” I suppress the response, “You are forgiven, my child.”

Why does it feel like a sin to struggle in math? Why are so many traumatized by their mathematics education? Is learning math worthwhile?

Sometimes agreeing and sometimes disagreeing, André and Simone Weil were the sort of siblings who would argue about such questions. André achieved renown as a mathematician; Simone was a formidable philosopher and mystic. André focused on applying algebra and geometry to deep questions about the structures of whole numbers, while Simone was concerned with how the world can be soul-crushing.

Both wrestled with the best way to teach math. Their insights and contradictions point to the fundamental role that mathematics and mathematics education play in human life and culture.

André Weil’s rigorous mathematics

André Weil, pictured here in 1956, was a prominent mathematician in the 20th century. Konrad Jacobs via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Unlike the prominent French mathematicians of previous generations, André, who was born in 1906 and died in 1998, spent little time philosophizing. For him, mathematics was a living subject endowed with a long and substantial history, but as he remarked, he saw “no need to defend (it).”

In his interactions with people, André was an unsparing critic. Although admired by some colleagues, he was feared by and at times disdainful of his students. He co-founded the Bourbaki mathematics collective that used abstraction and logical rigor to restructure mathematics from the ground up.

Nicolas Bourbaki’s commitment to proceeding from first principles, however, did not completely encapsulate his conception of what constituted worthwhile mathematics. André was attuned to how math should be taught differently to different audiences.

Tempering the Bourbaki spirit, he defined rigor as “(not) proving everything, but … endeavoring to assume as little as possible at every stage.”

The Bourbaki congress in 1938. Simone, pictured at front left, accompanies André, obscured at back left. Unknown author via Wikimedia Commons

In other words, absolute rigor has its place, but teachers must be willing to take their audience into account. He believed that teachers must motivate students by providing them meaningful problems and provocative examples. Excitement for advanced students comes in encountering the unknown; for beginning students, it emerges from solving questions of, as he put it, “theoretical or practical importance.” He insisted that math “must be a source of intellectual excitement.”

André’s own sense of intellectual excitement came from applying insights from one part of mathematics to other parts. In a letter to his sister, André described his work as seeking a metaphorical “Rosetta stone” of analogies between advanced versions of three basic mathematical objects: numbers, polynomials and geometric spaces.

André described mathematics in romantic terms. Initially, the relationship between the different parts of mathematics is that of passionate lovers, exchanging “furtive caresses” and having “inexplicable quarrels.” But as the analogies eventually give way to a single unified theory, the affair grows cold: “Gone is the analogy: gone are the two theories, their conflicts and their delicious reciprocal reflections … alas, all is just one theory, whose majestic beauty can no longer excite us.”

Despite being passionless, this theory that unifies numbers, polynomials and geometry gets to the heart of mathematics; André pursued it intensely. In the words of a colleague, André sought the “real meaning of every basic mathematical phenomenon.” For him, unlike his sister, this real meaning was found in the careful definitions, precisely articulated theorems and rigorous proofs of the most advanced mathematics of his time. Romantic language simply described the emotions of the mathematician encountering the mathematics; it did not point to any deeper significance.

Simone Weil and the philosophy of mathematics

On the other hand, Simone, who was born three years after André and died 55 years before him, used philosophy and religion to investigate the value of mathematics for nongeniuses, in addition to her work on politics, war, science and suffering.

Simone Weil, pictured here in 1925, was a prominent philosopher. Anonymous via Wikimedia Commons

All of her writing – indeed, her life – has a maddening quality to it. In her polished essays, as well as her private letters and journals, she will often make an extreme assertion or enigmatic comment. Such assertions might concern the motivations of scientists, the psychological state of a sufferer, the nature of labor, an analysis of labor unions or an interpretation of Greek philosophers and mathematicians. She is not a systematic thinker but rather circles around and around clusters of ideas and themes. When I read her writing, I am often taken aback. I start to argue with her, bringing up counterexamples and qualifications, but I eventually end up granting the essence of her point. Simone was known for the single-minded pursuit of her ideals.

Despite the discomfort her viewpoints provoke, they are worth engaging. Although her childhood was largely happy, her whole life she felt stupid in comparison with her brother. She channeled her feelings of inadequacy into an exploration of how to experience a meaningful existence in the face of oppression and affliction. Over her life, she developed an interpretation of beauty and suffering intertwined with geometry.

Along with her lifelong mathematical discussions with André, her views were influenced by one of her first jobs as a teacher. In a letter to a colleague, she described her pupils as struggling because they “regarded the various sciences as compilations of cut-and-dried knowledge.” Like André, Simone saw the ability to motivate students as the key to good teaching. She taught mathematics as a subject embedded in culture, emphasizing overarching historical themes. Even those students who were “most ignorant in science” followed her lectures with “passionate interest.”

For Simone, however, the primary purpose of mathematics education was to develop the virtue of attention. Mathematics confronts us with our mistakes, and the contemplation of these inadequacies brings the ability to concentrate on one thing, at the exclusion of all else, to the fore. As a math teacher, I frequently see students grit their teeth and furrow their brow, developing only a headache and resentment. According to Simone, however, true attention arises from joy and desire. We hold our knowledge lightly and wait with detached thought for light to arrive.

For Simone, the “first duty” of teachers is to help students develop, through their studies, the ability to apprehend God, which she conceptualized as a blending of Plato’s description of the ultimate Good with Christian conceptions of the self-abnegating God. A true understanding of God results in love for the afflicted.

Simone might even locate the lingering anxiety and frustration of many former math students in the absence of attention paid to them by their teachers.

Authors grapple with the Weil legacy

Recently, others have wrestled with the Weil legacy.

Sylvie Weil, André’s daughter, was born shortly before Simone’s death. Her family experience was that of being mistaken for her aunt, ignored or demeaned by her father and not being acknowledged and appreciated by those in her orbit.

Similarly, author Karen Olsson uses Simone and André to explore her own conflicted relationship with mathematics. Her forlorn quest to understand André’s mathematics eerily reflects Simone’s desire to understand André’s work and Sylvie’s desire to be seen as her own person, to not be in Simone’s shadow. Olsson studied with exceptional math teachers and students, all the while feeling out of place, overwhelmed and intimidated by her fellow students. Most painfully, in the process of writing her book on the Weil siblings, Olsson asks a mathematician, who had been a student with her, for help in understanding some aspect of André’s mathematics. She was ignored. Both Sylvie Weil and Karen Olsson are living witnesses to Simone’s observation that each of us cries out to be seen.

Christopher Jackson, on the other hand, gives testimony to how mathematics can live up to Simone’s vision. Jackson is incarcerated in a federal prison but found a new life through mathematics. His correspondence with mathematician Francis Su is the backbone of Su’s 2020 book “Mathematics for Human Flourishing,” which uses Simone’s observation that “every being cries out silently to be read differently” as a leitmotif. Su identifies aspects of mathematics that promote human flourishing, such as beauty, truth, freedom and love. In their own ways, both Simone and André would likely agree.

Scott Taylor is a professor of mathematics at Colby College in Waterville, Maine.

Disclosure statement

He receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the John and Mary Neff Foundation.

'Coursing through nature'

“Basin, Thoreau’s Remarkable Pothole’’ (digital achival print), by Tim Greenway, in his show “Tim Greenway: Waterways,’’ at Cove Street Art, Portland, Maine, through Sept. 28. (Image courtesy of Cove Street Art)

The gallery says the show uses photography to capture, in his words, "the peaceful yet powerful journey of water flowing from the untouched snowcaps of the White Mountains ... ultimately merging with the Maine coast." Tim Greenway's photography explores “the light, color and texture" of water coursing through nature.

‘Happy in a household calm’

Corridor 71, Spencer State Forest, Spencer, Mass. (Photo by John Phelan)

New England woods are fair of face,

And warm with tender, homely grace,

Not vast with tropic mystery,

Nor scant with arctic poverty,

But fragrant with familiar balm,

And happy in a household calm.

And such O land of shining star

Hitched to a cart! thy poets are,

So wonted to the common ways

Of level nights and busy days,

Yet painting hackneyed toll and ease

With glories of the Pleiades.

For Bryant is an aged oak,

Beloved of Time, and sober folk;

And Whittler, a hickory,

The workman's and the children's tree;

And Lowell is a maple decked

With autumn splendor circumspect.

Clear Longfellow's an elm benign,

With fluent grace in every line

And Holmes, the cheerful birch intent;

On frankest, whitest merriment

While Emerson's high councils rise;

A pine, communing with the skies.

— “New England Woods,’’ by Amos Russel Wells (1862-1933), American author, editor and professor. In this poem, corny to our ears, he cites some famous New England poets.

‘Sustainable art’ and tech

“Plastic Squirrel,’’ by Bordalo II, in the show “TRANSFORM: Reduce, Revive, Reimagine,'' at DATMA (Design, Art, Technology Massachusetts) in New Bedford.

DATMA says this a “public art series uniting sustainable art and cutting-edge technology. Lisbon street artist Bordalo II, known for his unique and impactful artwork that conveys powerful environmental messages, is showcasing an awe-inspiring, newly commissioned colorful animal sculpture called Plastic Rooster on view until 2029. Plus, a photography exhibition highlights technological innovations in robotics, marine research and exploration, and wind energy that are ushering in a transformative era for South Coast of Massachusetts. Additional public programs and workshops are available all summer. All exhibitions are outdoors, free and open to the public.’’

Nature-based ways to mitigate disasters

A coastal salt marsh in East Lyme, Conn., along Long Island Sound. Restoring coastal wetlands helps reduce the damage from storms and rising seas associated with global warming. (Photo by Alex756 )

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article by Frank Carini

“A new global assessment of scientific literature led by researchers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst found that nature-based solutions (NBS) are an economically effective method to mitigate risks from a range of disasters, including floods, hurricanes, and heat waves — all which are expected to intensify as the planet continues to warm.

“NBS solutions are interventions where an ecosystem is either preserved, sustainably managed, or restored to provide benefits to society and to nature. For instance, they can mitigate risk from a natural disaster, or facilitate climate mitigation and adaptation. They have emerged in combination with or as an alternative to engineering-based solutions, such as restoring wetlands to address coastal flooding rather than building a seawall.’’

The rise of Pittsfield

Downtown Pittsfield, Mass., in 2014

Pittsfield has in the past few years come to be called the “Brooklyn of The Berkshires” because its gentrifying neighborhoods and innovative arts programs are to the Berkshires’ more upmarket towns, such as Lenox, as a certain outer borough is to Manhattan.

‘Outside observer’

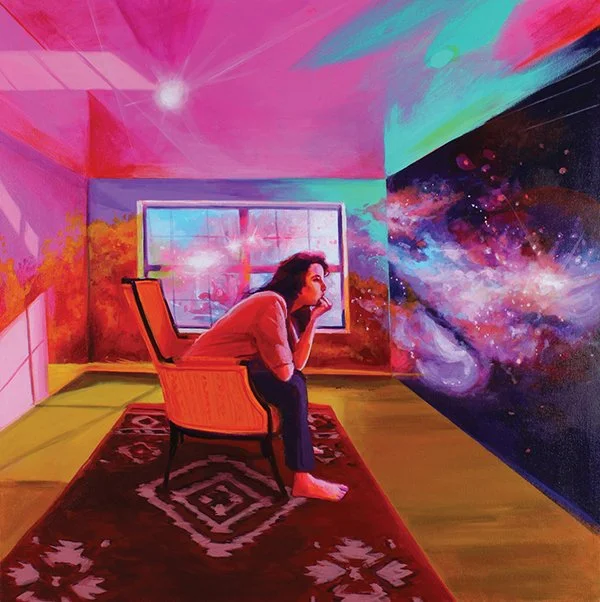

“Meanwhile, Galaxies Collide” (acrylic on canvas), by Medford, Mass.-based artist Bekka Teerlink, at the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass.

Her Web site says:

“Bekka Teerlink has no hometown; she moved frequently as a child which led her to escape into daydreams and build a sense of home in her mind to take wherever she went. She was always the outside observer which allowed her to see things fresh, and make connections in her mind between very different places, things, experiences that she collected along the way. In her work, she creates magical realist landscapes full of symbolism and suggestions of narrative and commentary on the world around her.’’

Chris Powell: Stop Conn utility agency from usurping taxing power; more casinos coming?

MA NCHESTER, Conn.

Even a few members of the Connecticut General Assembly's Democratic majority recently expressed alarm at the latest arrogance at the Public Utilities Control Authority — its raising electricity rates again.

This time the increase is to repay Connecticut's two largest electric utilities, Eversource and United Illuminating, for the millions of dollars the agency ordered them to spend reimbursing individuals and businesses for installing electric-car chargers. The program was meant to reduce climate change.

The program was silly, since even if Connecticut stopped using every kind of energy and reverted to a prehistoric way of life, it would have no bearing on climate change, nor on the introduction to the atmosphere of the "greenhouse gases" that climate hysterics believe will destroy the planet before Greta Thunberg grows up. China and the rest of the developing world will see that oil and coal remain the world's primary fuels for decades to come, until wind and solar power become much less expensive and more reliable.

Connecticut is far too small to measure in those calculations.

Stuffing the expense of somebody else's electric-car charger into ordinary electric bills, joining other expenses of government policies that have nothing to do with the generation and delivery of electricity, as Connecticut long has done, has always been beyond silly. It's offensive, because electricity, like food and medicine, is a necessity of life and commerce.

Leaders of the Republican minority in the General Assembly and even some ordinary citizens noted last week that the rate increases to pay for electric-car chargers are doubly offensive because they take more from the poor than the rich. Rate increases for electric-car chargers are essentially regressive taxes. Since electric cars are so expensive and less durable, only wealthy people can afford them. But while Democrats claim to be the party of the working class, they don't mind regressive taxes hidden in the fine print of electric bills.

But now soaring electric bills in Connecticut at last have prompted ordinary people to start questioning what have been euphemized as the "public benefits" hidden in those bills -- "benefits" such as charging people extra to make up for the people who don't pay.

Reporting on the controversy the other week, the Yankee Institute's Meghan Portfolio noted another reason why hiding EV charger costs in electric bills is offensive. That is, quite on its own three years ago the Public Utilities Control Authority required the electric companies to reimburse people and businesses for installing EV chargers and related equipment, making the costs payable to the electric companies through general rate increases.

This appropriation was made and its method of financing was levied without legislation enacted by the General Assembly and Gov. Ned Lamont. Portfolio writes: "PUCA's ability to impose sweeping mandates without legislative oversight has left ratepayers footing the bill for policies that disproportionately benefit a select few."

That is, Governor Lamont and the legislature have essentially delegated taxing power to an unelected agency. That's irresponsible and anti-democratic.

Republicans have asked the governor to call a special session of the legislature to undo some of the recent electric-rate increases. The governor says he is open to the idea -- that is, he'll call a special session if more people clamor for an end to the "public benefits" racket. People should take the hint.

MORE CASINOS COMING? Does Connecticut want more gambling casinos, and more casinos that operate from the authority of licenses awarded as ethnic privilege?

That question soon may become compelling. The other Connecticut's Hearst newspapers reported that the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs may reverse its position and invite the three state-recognized tribes in the western part of the state to reapply for the federal recognition that long ago was denied to them. Such recognition almost certainly will come with the same casino privileges enjoyed by the two federally recognized tribes in the southeastern part of the state.

If that happens, it will be time for the state to democratize casino licenses and let people get into the casino business regardless of their ancestry.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Old Boston commerce

Sent along by David Jacobs of The Boston Guardian

In the late '30's?:

Boylston Street, looking west from Massachusetts Avenue, was the approach to the Back Bay Fens, seen flanked by impressive Lombardy poplar trees.

On the left were low-rise office buildings with shops on the ground floor, such as the First National Store on the left, with Paparone Dancing Studio above, the tall Fenway Building, the Carlton Hotel and the Massachusetts Historical Society.

On the right was the Hotel Windermere and a row of well-designed limestone and brick four-story swell bay facade apartment buildings built by developers William B. Rice and Kilby Page. All were demolished in the early 1960s, when the Massachusetts Turnpike was put through the city.

David Ekbladh: Today’s world recalls the ‘30’s more than the Cold War

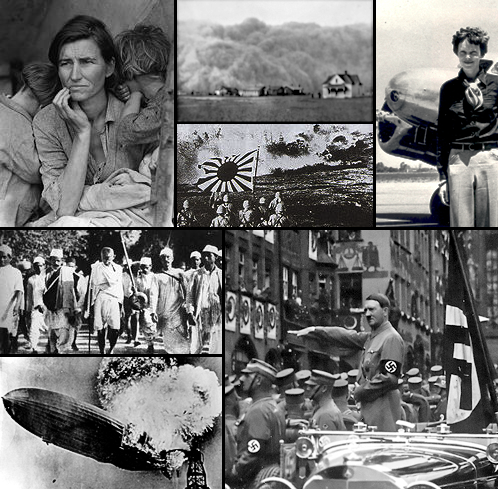

From Wikipedia: Montage of images from the '30's

MEDFORD, Mass.

The past decade and a half has seen upheaval across the globe. The 2008 financial crisis and its fallout, the COVID-19 pandemic and major regional conflicts in Sudan, the Middle East, Ukraine and elsewhere have left residual uncertainty. Added to this is a tense, growing rivalry between the U.S. and its perceived opponents, particularly China.

In response to these jarring times, commentators have often reached for the easy analogy of the post-1945 era to explain geopolitics. The world is, we are told repeatedly, entering a “new Cold War.”

But as a historian of the U.S.’s place in the world, these references to a conflict that pitted the West in a decades-long ideological battle with the Soviet Union and its allies – and the ripples the Cold War had around the globe – are a flawed lens to view today’s events. To a critical eye, the world looks less like the structured competition of that Cold War and more like the grinding collapse of world order that took place during the 1930s.

The ‘low dishonest decade’

In 1939, the poet W.H. Auden referred to the previous 10 years as the “low dishonest decade” – a time that bred uncertainty and conflict.

From the vantage of almost a century of hindsight, the period from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 to the onset of World War II can be distorted by loaded terms like “isolationism” or “appeasement.” The decade is cast as a morality play about the rise of figures like Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and simple tales of aggression appeased.

But the era was much more complicated. Powerful forces in the 1930s reshaped economies, societies and political beliefs. Understanding these dynamics can provide clarity for the confounding events of recent years.

Greater and lesser depressions

The Great Depression defined the 1930s across the world. It was not, as it is often remembered, simply the stock market crash of 1929. That was merely an overture to a large-scale unraveling of the world economy that lasted a painfully long time.

Persistent economic problems impacted economies and individuals from Minneapolis to Mumbai, India, and wrought profound cultural, social and, ultimately, political changes. Meanwhile, the length of the Great Depression and its resistance to standard solutions – such as simply letting market forces “purge the rot” of a massive crisis – discredited the laissez faire approach to economics and the liberal capitalist states that supported it.

The “Lesser Depression” that followed the 2008 financial crisis produced something similar – throwing international and domestic economies into chaos, making billions insecure and discrediting a liberal globalization that had ruled since the 1990s.

In both the greater and lesser depressions, people around the world had their lives upended and, finding established ideas, elites and institutions wanting, turned to more radical and extreme voices.

The 1929 stock market crash resulted in a loss of trust for financial institutions. AP Photo

It wasn’t just Wall Street that crashed; for many, the crisis undercut the ideology driving the U.S. and many parts of the world: liberalism. In the 1930s, this skepticism bred questions of whether democracy and capitalism, already beset with contradictions in the form of discrimination, racism and empire, were suited for the demands of the modern world. Over the past decade, we have similarly seen voters turn to authoritarian-leaning populists in countries around the world.

American essayist Edmund Wilson lamented in 1931: “We have lost … not merely our way in the economic labyrinth but our conviction of the value of what we are doing.” Writers in major magazines accounted for “why liberalism is bankrupt.”

Today, figures on the left and right can similarly share in a view articulated by conservative political scientist Patrick Deneen in his book, “Why Liberalism Failed.”

Ill winds

Liberalism – an ideology broadly based on individual freedoms and rule of law as well as a faith in private property and the free market – was touted by its backers as a way to bring democratization and economic prosperity to the world. But recently, liberal “globalization” has hit the skids.

The Great Depression had a similar effect. The optimism of the 1920s – a period some called the “first wave” of democratization – collapsed as countries from Japan to Poland established populist, authoritarian governments.

A Japanese military parade on the second anniversary of the Sino-Japanese conflict in Manchuria. Imagno/Getty Images

The rise today of figures like Hungary’s Victor Orban, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and China’s Xi Jinping remind historians of the continuing appeal of authoritarianism in moments of uncertainty.

Both eras share a growing fragmentation in the world economy in which countries, including the U.S., tried to staunch economic bleeding by raising tariffs to protect domestic industries.

Economic nationalism, although hotly debated and opposed, became a dominant force globally in the 1930s. This is mirrored by recent appeals of protectionist policies in many countries, including the U.S.

A world of grievance

While the Great Depression sparked a “New Deal” in the United States where the government took on new roles in the economy and society, elsewhere people burned by the implosion of a liberal world economy saw the rise of regimes that placed enormous power in the hands of the central government.

The appeal today of China’s model of authoritarian economic growth, and the image of the strongman embodied by Orban, Putin and others – not only in parts of the “Global South” but also in parts of the West – echoes the 1930s.

The Depression intensified a set of what were called “totalitarian” ideologies: fascism in Italy, communism in Russia, militarism in Japan and, above all, Nazism in Germany.

Importantly, it gave these systems a level of legitimacy in the eyes of many around the world, particularly when compared to doddering liberal governments that seemed unable to offer answers to the crises.

Some of these totalitarian regimes had preexisting grievances with the world established after World War I. And, after the failure of a global order based on liberal principles to deliver stability, they set out to reshape it on their own terms.

Observers today may express shock at the return of large-scale war and the challenge it poses to global stability. But it has a distinct parallel to the Depression years.

Early in the 1930s, countries like Japan moved to revise the world system through force – hence the reason such nations were known as “revisionist.” Slicing off pieces of China, specifically Manchuria in 1931, was met — not unlike Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014 — with little more than nonrecognition from the Western democracies.

As the decade progressed, open military aggression spread. China became a bellwether as its anti-imperial war for self-preservation against Japan was haltingly supported by other powers. Ukrainians today might well understand this parallel.

Ethiopia, Spain, Czechoslovakia and eventually Poland became targets for “revisionist” states using military aggression, or the threat of it, to reshape the international order in their own image.

Ironically, by the end of the 1930s, many living through those crisis years saw their own “cold war” against the regimes and methods of states like Nazi Germany. They used those very words to describe the breakdown of normal international affairs into a scrum of constant, sometimes violent, competition. French observers described a period of “no peace, no war” or a “demi guerre.”

Figures at the time understood that it was less an ongoing competition than a crucible for norms and relationships being forged anew. Their words echo in the sentiments of those who see today the forging of a new multipolar world and the rise of regional powers looking to expand their own local influences.

Taking the reins

It is sobering to compare our current moment with one in the past whose terminus was global war.

Historical parallels are never perfect, but they do invite us to reconsider our present. Our future neither has to be a reprise of the “hot war” that concluded the 1930s, nor the Cold War that followed.

The rising power and capabilities of countries like Brazil, India and other regional powers remind one that historical actors evolve and change. However, acknowledging that our own era, like the 1930s, is a complicated multipolar period, buffeted by serious crises, allows us to see that tectonic forces are again reshaping many basic relationships. Comprehending this offers us a chance to rein in forces that in another time led to catastrophe.

David Ekbladh is a professor of history at Tufts University, in Medford, Mass.

Disclosure statement

David Ekbladh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

Beautiful, at least at night

“Fogging in Twin River,’’ by Massachusetts artist Jurgen Lobert, in his show “Industrial Beauty,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through Nov. 3

— Image courtesy Art Complex Museum

The museum says:

Lobert demonstrates that "that industrial views ... can appear like a tourist attraction at night, because night photography is transformative.’’

Lilly opens big R&D center in Boston’s Seaport District

Eli Lilly's Lilly Seaport Innovation Center

Edited from a New England Council report

On Aug. 13, Eli Lilly and Company announced the opening of the Lilly Seaport Innovation Center (LSC), a research-and-development facility in Boston’s Seaport District dedicated to furthering the company’s efforts in RNA and DNA-based therapies and discovering new drug targets to create transformative medicines for a range of conditions.

Lilly aims to use innovative biotechnology and medicine to create solutions to major health challenges. The new site will house the first Lilly Gateway Labs location on the East Coast, encouraging a culture of shared expertise and real-time learning to promote the development of novel medicines.

“The opening of LSC expands upon Lilly’s long-standing presence in the Boston area,” said Daniel Skovronsky, M.D., Ph.D., Lilly’s chief scientific officer and president of Lilly Research Laboratories and Lilly Immunology. ‘‘We are committed to being supportive neighbors in this hub of discovery and innovation, furthering collaborating with leading institutions and new talent to continue delivering transformative medicines for the people who need them the most.”

Nosy in New Hampshire

Peterboro, N.H., in 1907, during the period in which Our Town is set.

“In our town, we like to know the facts about everybody.’’

— From Thornton Wilder’s (1897-1975) celebrated 1938 play Our Town, inspired by the time Wilder spent in Peterboro, N.H., where he had been a member of the MacDowell Colony, the residential retreat for artists.

Llewellyn King: A soldier of fortune’s plan to hook up Puerto Rico and beyond

Adam Rousselle

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Some men go to war and come back broken. Others come back and black out that experience. Some are never whole again.

But some leave active duty inspired to help, to change things they can for the better. Adam Rousselle is such a man.

Rousselle saw service fighting with the Contras in Honduras and later was on active duty in Iraq, fighting in Operation Desert Storm. He left the U.S. Army with a disability, having ascended from private to officer, and set out to be an entrepreneur. His aim was to do good as well as provide a life for himself and his young bride.

Returning to Honduras, he founded a mahogany-exporting company. It was a smashing success until he ran afoul of the government and shady operators.

Suddenly, Rousselle was accused of taking mahogany trees illegally, although he said he was scrupulous in cutting only trees identified for removal by the Honduran government.

His staff and his father were imprisoned. His father died in prison — an open-air enclosure without shelter. But Rousselle still had to get his staff released and his name cleared.

His solution: Identify and inventory the trees in the Honduran rainforest. Call in science, can-do thinking and a new satellite application.

Working with NASA images from space, Rousselle was able to put every mahogany tree into a database and to identify the maturity and health of each tree through the signature of the crown. Millions of trees were identified, and Rousselle was able to prove that the trees he was supposed to have cut illegally were alive and well in the rainforest.

Rousselle was exonerated and his staff was freed, after three and a half years in detention, with help from Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). With the new science of tree identification, Rousselle helped Boise Cascade Co. to inventory its entire timberland holdings, and electric utilities have been able to identify and remove dead trees in high wildfire-risk areas.

Another of Rousselle’s innovations was an energy-storage system, using abandoned quarries as micropump storage sites. “These are all over every country, close to the highest energy demand centers,” Rousselle said. He got many of these permitted and others are being examined.

As I write, a quarter of Puerto Rico’s 3.22 million people are without electricity after Hurricane Ernesto swept through their island. Ernesto has left slightly less damage than Hurricane Maria in 2017. In that hurricane, more than a third of the island was plunged into darkness and some communities were without power for nine months.

For several years, Rousselle has been working on a plan to help Puerto Rico by supplying electricity via cable from the U.S. mainland.

It is a grand engineering project that would, Rousselle said, cut the cost of electricity on the island in half and ensure hurricane-proof supply. While it wouldn’t deal with the problem of the Puerto Rican grid’s fragility, it would solve the generation problem on the island, which is outdated and based on imported diesel and coal, both very polluting. Also, it would help solve the bulk transmission problem.

The Biden administration and a swathe of the U.S. energy establishment would like to replace that electricity generation with renewables, such as wind and solar.

But Rousselle pointed out that on-island wind and solar would both be highly vulnerable in future hurricanes. Green electricity is well and good, but generated securely on the U.S. mainland is best, Rousselle said.

He said that his 1,850-mile, undersea cable project would deliver 2,000 megawatts of electricity from a substation in South Carolina to a substation in Puerto Rico. That would leave the Puerto Rico electric supply system free to concentrate on upgrading the fragile island grid.

Worldwide, there is a lot of activity in undersea electricity transmission. All are aimed at bringing renewable electricity from where there is an abundant wind and solar resource to where it is needed. The two most ambitious plans: One to link Australia and Singapore (2,610 miles) and another to link Morocco to the United Kingdom (2,360 miles). There is also a plan to hookup Greece, Cyprus and Israel via undersea cable.

The longest cable of this type (447 miles) went into operation last year, bringing Danish wind power to the UK.

One way or another, undersea electricity transmission is here and it is the future.

After Puerto Rico, Rousselle, ever the soldier of fortune, hopes to hook up the entire Caribbean Basin in an undersea grid, moving green energy out of the reach of tropical storms.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Showing the blues in Worcester

“Blue” (handmade paper pulp drawing, specimen pins), by Michelle Samour, in the group show “Blue Profundity: Contemporary Artists Revisit a Color,’’ at the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Art Gallery, at the College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester.

The gallery says:

“The exhibition features contemporary artists who incorporate blue in their work to highlight the symbolic and historic meanings of the color.’’

Gabe Sender: A plan to extend Brown’s greenery and social spirit

In 2012, Brown University purchased the rights to three city streets and 250 parking spaces from the City of Providence for $31.5 million. The agreement seemed to be a victory for both sides at the time: Providence was able to stabilize its finances, and Brown immediately contracted architects to draft plans for the streets’ pedestrianization. However, while this agreement let Providence move past some of its immediate fiscal troubles, for Brown the streets remain glorified parking lots in the heart of campus more than a decade later. This costly investment has not led to any improvement in student life, and the streets remain frozen in time.

The streets that it bought are a two-block stretch of Brown Street, between George and Charlesfield streets; Benevolent Street between Brown and Bannister Street (formerly Magee), and Olive Street, between Brown and Thayer. For Brown and Benevolent streets, the university engaged the landscape-architecture firm Rader + Crews to develop plans for pedestrianization. These streets are essential to campus mobility, being between several large dormitories and the bucolic Main Green. Rader + Crews proposed to close the streets to vehicular traffic, remove all parking spots, and replace the 51,500 square feet of asphalt with new pavers, rain gardens and benches for congregating.

A view of the proposal by Rader + Crews, with a rough plan for transforming Brown and Benevolent streets.

Ultimately, despite its potential benefits, this plan ended up a victim of circumstance. In one of former Brown President’s Ruth J. Simmons’s final actions, she had Brown buy these streets and authorized plans to redevelop them. But when current President Christina H. Paxson took office, the street pedestrianization was slowly forgotten in favor of other institutional priorities. Today the project remains Brown’s biggest unrealized opportunity. This would be a low-cost undertaking which would have an outsized impact both environmentally and socially, and would dovetail perfectly with the campus’s centuries of evolution.

In the past decade, Brown has seen significant growth. Since 2014, undergraduate enrollment has increased by 1,009 students, or about 16 percent, to about 7,222, and its graduate enrollment by about the same percentage, to about 3,000 (excluding medical students). Brown has gone on a billion-dollar building spree to accommodate the needs of this increased student body, constructing three new dormitories, countless new classrooms and research facilities, and extensively renovating its recreational facilities. Yet Brown’s open spaces have remained virtually unchanged over this same period. The need for new green spaces only grows more pressing as the campus becomes more crowded. The pedestrianization project is oriented toward improving Brown’s social future by enhancing the quality of life on campus.

First, the pedestrianization plan promises to strengthen Brown’s sense of community. The university’s thriving academic and extracurricular environment is rooted in its vibrant community, which can only blossom if it has the space to do so. The Main Green is the embodiment of this “Brown spirit.’’ An observer on a sunny day sees undergraduates, graduates, alumni and faculty all socializing in that welcoming space. Converting Brown Street and a stretch of Benevolent Street to pedestrian promenades would extend this spirit southward. These streets currently serve as the busiest arteries for pedestrians and bicyclists between North and South Campus. However, due to the volume of people using the narrow sidewalks, few linger on these streets. Pedestrianizing them would open them up to the kinds of interpersonal experiences that help define Brown and allow its community spirit to grow with its growing student body.

Second, Brown is increasingly affected by climate change, and its effects are especially felt along Brown Street.

View, looking north, on Brown Street as it could look if this project were realized.

Over the past three years the Keeney Quadrangle dormitory has flooded during heavy summer rains, which have grown in intensity in the past decade. This dorm is on the corner of Brown and Benevolent streets and houses hundreds of Brown freshmen. As a result, some students’ introduction to their college experience is a rushed evacuation from their dorms as water pours into their rooms. This is clearly untenable. The full implementation of the pedestrianization program would prevent such events from occurring again. The Rader + Crews plan would address excess water flowing through the streets by directing it away from buildings and planting rain gardens to slow water flow. Indeed, Brown’s overall environment would improve with the new plantings, which would absorb air pollution, and using lighter paving materials would reduce the area’s temperatures.

It's a disservice to the ambience of Brown’s campus to let this project remain dormant. Brown’s eclectic mix of wonderfully ornate and innovative architecture, coupled with its vibrant green spaces, delight students, faculty and the larger community. The Quiet (aka Front) Green, between Prospect Street and University Hall, and the Main Green are central to the feel of campus because they lie in its heart and because they are beautiful and relaxing spaces in which to interact. Brown and Benevolent Streets should be such a space – modern greens adding to the beauty of Brown’s campus. No spaces are better suited for such a transformation, and in its most ideal vision, they can become an extension of the Main Green, thus enlarging Brown’s campus spirit.

Brown Street circa 1900, when it passed through the Main Green.

The project I envision is not without precedent. In fact, Brown has a long history of street conversions, in an effort to consolidate its campus. Before 1900, Brown Street ran straight along the east edge of the Main Green. Much more recently, one of President Simmons’s crowning achievements was construction of The Walk, a green pedestrian path that extends from Simmons Quad to Meeting Street and unites the two halves of campus. Once known as Dumpster Alley, students would negotiate this path, which mostly consisted of parking lots, a gas station and various back alleys, to traverse this distance. Beginning in 2003, and led by the Rader + Crews design team, Brown converted these spaces into a unified tree-lined path that revolutionized the feel of the campus.

Today, Brown faces a momentous turning point. I have spent the past three years working with a dedicated group of students and alumni, the Brown Pedestrianization Initiative, to bring this project to fruition. While many in the Brown community favor it, the pedestrianization plan will fade from memory again unless a donor, or group of donors, steps forward to fund the project. In what would be the perfect capstone to the incredibly successful BrownTogether campaign, Brown’s campus may once again be revolutionized, continuing its cherished tradition of human-scale design. It is a plan whose time has come.

Gabriel Sender, Brown Class of 2025, is founder and president of the Brown Pedestrianization Initiative.

Brown Street looking south, from the Rader + Crews plan.

'Imagined environments'

Painting by New York City-based artist Peter Hamlin, in the group show “Octopus’s Garden,’’ at Kenise Barnes Fine Art, Kent, Conn., through Aug. 25.

The gallery says:

“Envisioning a future in which technology is indistinguishable from life, Peter Hamlin blends fantasy and science in compositions that breathe with awareness and futuristic hybridity in vibrant color, synthetic layers and meticulous, delineated systems. In Hamlin’s imagined environments, nanopeople, robots, cyborg plants and curious otherworldly organisms coexist. The artist’s work explores how we adapt as a species, determine our future and prepare for what’s to come as technologies radically change how humans experience and interact with the world. The precision and exactitude with which Hamlin paints seduces the viewer with beauty and beckons one into his supernatural world. ‘‘

Kent Falls, in Kent Falls State Park.

Debby Waldman: Driving to Vermont to arrange to die

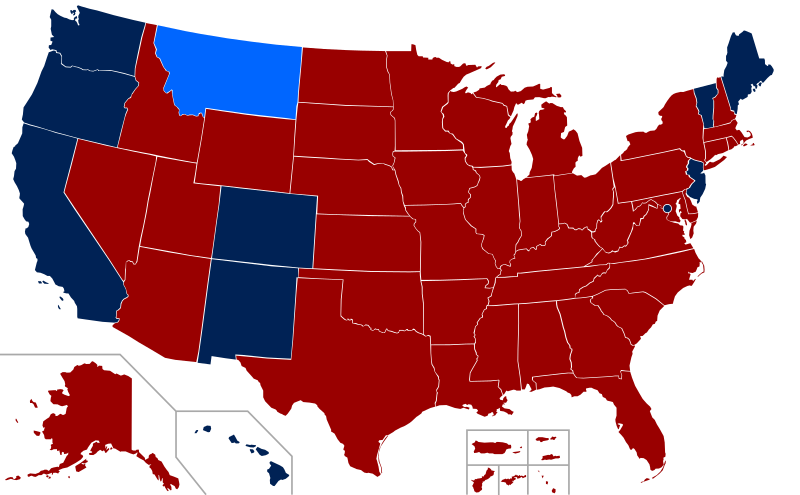

Legality of assisted suicide in the U.S. It’s clearly legal in dark blue states, legal in light blue Montana under a court order and illegal in red states.

Text From Kaiser Family Health News

In the 18 months after Francine Milano was diagnosed with a recurrence of the ovarian cancer she thought that she’d beaten 20 years ago, she traveled twice from her home in Pennsylvania to Vermont. She went not to ski, hike, or leaf-peep, but to arrange to die.

“I really wanted to take control over how I left this world,” said the 61-year-old who lives in Lancaster. “I decided that this was an option for me.”

Dying with medical assistance wasn’t an option when Milano learned in early 2023 that her disease was incurable. At that point, she would have had to travel to Switzerland — or live in the District of Columbia or one of the 10 states where medical aid in dying was legal.

But Vermont lifted its residency requirement in May 2023, followed by Oregon two months later. (Montana effectively allows aid in dying through a 2009 court decision, but that ruling doesn’t spell out rules around residency. And though New York and California recently considered legislation that would allow out-of-staters to secure aid in dying, neither provision passed.)

Despite the limited options and the challenges — such as finding doctors in a new state, figuring out where to die, and traveling when too sick to walk to the next room, let alone climb into a car — dozens have made the trek to the two states that have opened their doors to terminally ill nonresidents seeking aid in dying.

At least 26 people have traveled to Vermont to die, representing nearly 25% of the reported assisted deaths in the state from May 2023 through this June, according to the Vermont Department of Health. In Oregon, 23 out-of-state residents died using medical assistance in 2023, just over 6% of the state total, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

Oncologist Charles Blanke, whose clinic in Portland is devoted to end-of-life care, said he thinks that Oregon’s total is likely an undercount and he expects the numbers to grow. Over the past year, he said, he’s seen two to four out-of-state patients a week — about one-quarter of his practice — and fielded calls from across the U.S., including New York, the Carolinas, Florida and “tons from Texas.” But just because patients are willing to travel doesn’t mean it’s easy or that they get their desired outcome.

“The law is pretty strict about what has to be done,” Blanke said.

As in other states that allow what some call physician-assisted death or assisted suicide, Oregon and Vermont require patients to be assessed by two doctors. Patients must have less than six months to live, be mentally and cognitively sound, and be physically able to ingest the drugs to end their lives. Charts and records must be reviewed in the state; neglecting to do so constitutes practicing medicine out of state, which violates medical-licensing requirements. For the same reason, the patients must be in the state for the initial exam, when they request the drugs, and when they ingest them.

State legislatures impose those restrictions as safeguards — to balance the rights of patients seeking aid in dying with a legislative imperative not to pass laws that are harmful to anyone, said Peg Sandeen, CEO of the group Death With Dignity. Like many aid-in-dying advocates, however, she said such rules create undue burdens for people who are already suffering.

Diana Barnard, a Vermont palliative-care physician, said some patients cannot even come for their appointments. “They end up being sick or not feeling like traveling, so there’s rescheduling involved,” she said. “It’s asking people to use a significant part of their energy to come here when they really deserve to have the option closer to home.”

Those opposed to aid in dying include religious groups that say taking a life is immoral, and medical practitioners who argue their job is to make people more comfortable at the end of life, not to end the life itself.

Anthropologist Anita Hannig, who interviewed dozens of terminally ill patients while researching her 2022 book, The Day I Die: The Untold Story of Assisted Dying in America, said she doesn’t expect federal legislation to settle the issue anytime soon. As the U.S. Supreme Court did with abortion in 2022, it ruled assisted dying to be a states’ rights issue in 1997.

During the 2023-24 legislative sessions, 19 states (including Milano’s home state of Pennsylvania) considered aid-in-dying legislation, according to the advocacy group Compassion & Choices. Delaware was the sole state to pass it, but the governor has yet to act on it.

Sandeen said that many states initially pass restrictive laws — requiring 21-day wait times and psychiatric evaluations, for instance — only to eventually repeal provisions that prove unduly onerous. That makes her optimistic that more states will eventually follow Vermont and Oregon, she said.

Milano would have preferred to travel to neighboring New Jersey, where aid in dying has been legal since 2019, but its residency requirement made that a nonstarter. And though Oregon has more providers than the largely rural state of Vermont, Milano opted for the nine-hour car ride to Burlington because it was less physically and financially draining than a cross-country trip.

The logistics were key because Milano knew she’d have to return. When she traveled to Vermont in May 2023 with her husband and her brother, she wasn’t near death. She figured that the next time she was in Vermont, it would be to request the medication. Then she’d have to wait 15 days to receive it.

The waiting period is standard to ensure that a person has what Barnard calls “thoughtful time to contemplate the decision,” although she said most have done that long before. Some states have shortened the period or, like Oregon, have a waiver option.

That waiting period can be hard on patients, on top of being away from their health-care team, home, and family. Blanke said he has seen as many as 25 relatives attend the death of an Oregon resident, but out-of-staters usually bring only one person. And while finding a place to die can be a problem for Oregonians who are in care homes or hospitals that prohibit aid in dying, it’s especially challenging for nonresidents.

When Oregon lifted its residency requirement, Blanke advertised on Craigslist and used the results to compile a list of short-term accommodations, including Airbnbs, willing to allow patients to die there. Nonprofits in states with aid-in-dying laws also maintain such lists, Sandeen said.

Milano hasn’t gotten to the point where she needs to find a place to take the meds and end her life. In fact, because she had a relatively healthy year after her first trip to Vermont, she let her six-month approval period lapse.

In June, though, she headed back to open another six-month window. This time, she went with a girlfriend who has a camper van. They drove six hours to cross the state border, stopping at a playground and gift shop before sitting in a parking lot where Milano had a Zoom appointment with her doctors rather than driving three more hours to Burlington to meet in person.

“I don’t know if they do GPS tracking or IP address kind of stuff, but I would have been afraid not to be honest,” she said.

That’s not all that scares her. She worries she’ll be too sick to return to Vermont when she is ready to die. And, even if she can get there, she wonders whether she’ll have the courage to take the medication. About one-third of people approved for assisted death don’t follow through, Blanke said. For them, it’s often enough to know they have the meds — the control — to end their lives when they want.

Milano said she is grateful she has that power now while she’s still healthy enough to travel and enjoy life. “I just wish more people had the option,” she said.

In June, Milano headed to Vermont to open a second six-month window to receive medical aid in dying. After a six-hour drive, she crossed the state’s border and opted to Zoom with a doctor rather than drive three more hours to meet in person, as she had done the first time.

Debby Waldman is a Kaiser Family Health Plans journalist.

Related Topics

'The Wall' and fireflies

"The Wall'' at Hampton Beach, N.H.

Resting on Hampton Beach on a quiet September day.

“When the summer days end, the beauty of New England does not. Summer nights are arguably the best time of day. At the end of the day, we enjoy the most beautiful sea breeze. I’ve spent so many nights wrapped in a sweatshirt on the porch, counting the fireflies lighting up the yard. This weather also makes for the perfect bonfire. If we’re not at “The Wall, ‘‘ {in Hampton Beach, N.H.) it’s very likely that someone will have a fire in his/her yard. If you haven’t huddled up to a fire with your best friends, then I recommend doing so this summer (just make sure someone brings the ingredients for s’mores!).’’

— Abigail Loffredo, from her “New England Summers are the BEST Summers’’

Primacy in plumbing

Edited from From The Boston Guardian

In 1829, the Tremont Hotel opened at the corner of Tremont and Beacon streets in downtown Boston. It had 170 rooms that each rented for $2 a day and included four meals. In 1869 the Tremont became the first hotel in the U.S. to install indoor plumbing. Notable guests included Davy Crockett and Charles Dickens. In 1895, the hotel was razed and replaced with an office building.