Paul Armentano: Does it matter if pot is stronger these days?

Flowering cannabis (marijuana) plant

Via OtherWords.org

I’ve worked in marijuana policy reform for nearly 30 years. Throughout my career, opponents of legalization have alleged that “today’s” pot is far more potent — and therefore more dangerous — than the cannabis of prior generations.

For instance, former Drug Czar William Bennett claimed in 1990 that if people from the late 1960s “suck on one of today’s marijuana cigarettes, they’d fall down backwards.”

His successor, Lee Brown, claimed in 1995 that “marijuana is 40 times more potent today” than it was decades ago. Not to be outdone, then-Delaware Sen. Joe Biden opined in 1996: “It’s like comparing buckshot in a shotgun shell to a laser-guided missile.”

Taking their hyperbole at face value, the message is clear: Modern marijuana is exponentially stronger and more harmful than the weak, nearly impotent weed of yesteryear.

But that’s not what the drug warriors of yesteryear warned.

During the 1930s, Henry Anslinger, Commissioner of the Bureau of Narcotics, testified to Congress that cannabis is ”entirely the monster Hyde, the harmful effect of which cannot be measured.”

Decades later, in the 1960s and ‘70s, public officials argued that the pot of their era was even stronger. They claimed that smoking “Woodstock weed” would permanently damage brain cells — and that, therefore, possession needed to be heavily criminalized to protect public health.

By the late 1980s, former Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl F. Gates opined that advanced growing techniques had increased THC potency to the point that “those who blast some pot on a casual basis… should be taken out and shot.”

Now a new generation of prohibitionists are recycling the same old claims and scare tactics in a misguided effort to re-criminalize more potent cannabis products in states where their production and sale is legal.

Most recently, these calls have even come from the Senate, including from Senators Diane Feinstein (D-Calif.) and John Cornyn (R-Texas).

So, is there any truth to the claim that today’s weed is so much stronger?

According to marijuana potency data compiled annually by the University of Mississippi at Oxford since the 1970s, one thing is true: The average amount of THC in domestically produced marijuana has increased over time.

But does this elevated potency equate to an increased safety risk? Not necessarily.

Higher-potency cannabis products, such as hashish, have always existed. Marijuana is still the same plant it has always been — with most of the increase in strength akin to the difference between beer and wine, or between a cup of tea and an espresso.

Consuming too much THC at one time can be temporarily unpleasant. But studies have as of yet failed to identify any independent relationship between cannabis use and mental, physical, or psychiatric illnesses.

Furthermore, THC — regardless of potency or quantity — cannot cause death by lethal overdose. Alcohol, by contrast, is routinely sold in lethal dose quantities. Drinking a handle of vodka could easily kill a person, yet vodka is available in liquor stores throughout the country.

Just as alcohol is available in a variety of potencies, from light beer to hard liquor, so is cannabis. So most users regulate their intake accordingly.

Also like with alcohol, cannabis products of the highest potency comprise a far smaller share of the legal marketplace than do more moderately potent products, like flower. According to data published last year in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, nearly eight in ten cannabis consumers prefer herbal cannabis over higher-potency infused concentrates.

Virtually no one thinks alcohol over a certain potency should be re-criminalized. The same should be true of cannabis.

Instead, we should simply make sure consumers know how much THC is in the products they consume and what the effects may be. And we need more diligence from regulators to ensure that legal products for adults don’t get diverted to the youth market.

In other words, let’s address public health concerns with facts, not hyperbole.

Paul Armentano is the deputy director of NORML, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. He’s the co-author, with Steve Fox and Mason Tvert, of Marijuana Is Safer: So Why Are We Driving People to Drink?

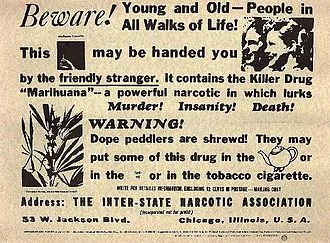

Anti-marijuana ad from 1935

Who is stoned on the road?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I’ve been worried a long time about the increasing number of people driving around here stoned on marijuana in varying degrees, with outlets selling “medical marijuana,’’ as well as illegal sales of “recreational” pot, in Rhode Island, and with recreational, as well as medical, marijuana legal in Massachusetts. (The Feds have some different ideas about all this.) A big problem is that unlike with alcohol, there seems to be no precise metric to measure when somebody might be impaired by pot.

The issue was front and center in a Nov. 6 Providence Journal story, “Judge ponders: Can impairment by pot be measured,” involving Marshall Howard, charged with driving under the influence, death resulting, in the 2017 death of David Bustin. Mr. Howard’s car hit Mr. Bustin after he had stepped into the street. A blood test showed that Mr. Howard had THC, the mind-altering ingredient in marijuana, in his system at the time. Mr. Howard also had fentanyl and heroin in his car; Mr. Bustin, for his part, was apparently drunk.\

Inebriated America? Are that many people in need of psychic or physical relief?

The story, by Katie Mulvaney, quoted the Superior Court judge in the case, Daniel Procaccini, as saying:

“We don’t have any way to correlate any amount of a substance {such as THC} in a person’s blood to impairment. With alcohol we do.’’ This is a national problem, which we’d better address as throngs hit the road after toking up.

Thank God cars themselves are much safer now than a few decades ago since drivers seem to be ever more distracted.

To read the Massachusetts angle on this, please hit this link.

States' addiction promotion

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As they did with gambling (which can be highly addictive), states, including Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut, are jumping into the marijuana business. Massachusetts (along with Maine and Vermont) has fully legalized pot use and Rhode Island and Connecticut have decriminalized its “recreational’’ use. Meanwhile, it’s full speed ahead for “medical marijuana,’’ which some truly sick people use, along with others who just want to get stoned.

For the states, it’s all about trying to find new ways of increasing government revenue without raising broad-based taxes, which is usually political poison. It’s a regressive way of doing it since those wanting to gamble and smoke pot tend to be in lower socio-economic levels. Some old-fashioned types might even call this addiction promotion immoral.

Pot promoters, for their part, have long asserted that it’s not a “gateway drug’’ – an assertion that has always struck me as dubious. Perhaps they should read a new paper, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, in which researchers looking at states that enacted medical marijuana laws saw a 23 percent increase in opioid-overdose deaths. There are lots of people with addiction tendencies. And use of one drug leads, in many people, to a desire for stronger ones.

Other studies have shown a high incidence among opiate addicts of the use and abuse of other drugs, be they amphetamines, alcohol, nicotine or others.

To read the study, please hit this link.

Pot in the air

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

As Rhode Island, Massachusetts and some other states (if not the Feds) loosen laws against marijuana cultivation and use, pot smokers are becoming increasingly noxious neighbors in apartment and condo buildings. I have noticed the rich aroma of the stuff in some buildings and certainly on many sidewalks.

Reminder: Marijuana cultivation, sale and use are still prohibited under federal law, which presents considerable confusion in states that allow sale and use of the stuff anyway. The Feds have long looked the other way on this, fearing that the federal law is just too difficult to enforce, considering some states’ policies and that millions of people regularly smoke pot.

Non-pot smokers are being forced to inhale this psychotropic smoke, which, to say the least, is unhealthy. Of course, breathing second-hand tobacco smoke is bad for you, too, but it doesn’t affect your clarity of mind as marijuana smoke does. In some places, you can become involuntarily intoxicated.

Pot has become such a big business and tax-revenue supplier that, barring rigorous enforcement of federal laws still on the books, the problem of second-hand smoke can only get worse. And I laugh at the argument that states’ effective legalization of the weed primarily serves as a way to alleviate physical pain. Most people smoking pot just want to get mildly or very stoned for the pleasure of it, and there’s much profit and tax money to be made from the stuff.

To read an entertaining Boston Globe story on second-hand pot smoke, please hit this link.

Chris Powell: What kind of a state would depend on money from casinos and potheads?

At the Connecticut state Capitol the issue is being framed as whether Connecticut should legalize marijuana. But that's not really the issue at all, since marijuana long has been effectively legal in the state for several reasons: because of its common use and the reluctance of courts to punish people for it; because possession of small amounts has been reduced to an infraction; because marijuana production and sales have been legalized for medical purposes; and because the federal government has stopped enforcing its own law against marijuana in those states that don't want it enforced.

The real issue is whether state government should get into the marijuana business -- licensing dealers and taxing sales in the hope of raising as much as $100 million a year to offset state government's financial collapse. Such a scheme would introduce marijuana to many more people, especially minors, who, even if the age for purchase is set at 21, will get it from their older friends, just as minors now get alcohol.

As has happened with legalization in Colorado, many more students will come to school stoned or get stoned there. Intoxicated driving will increase, even if much of the increase will result from Connecticut's refusal to prosecute first offenses. And since Connecticut's criminal sanctions against marijuana have largely disappeared already, legalization won't give the state much financial relief on the criminal-justice side of the budget.

There's another problem with licensing and taxing: It would constitute nullification of federal drug law. Nothing obliges Connecticut's criminal statutes to match the federal government's, but licensing and taxing, profiting from federal crimes, is secession -- and unless federal drug law was changed, the federal government could smash Connecticut's marijuana infrastructure at any time. In any case the half-century of President Nixon's "war on drugs" has shown that drug criminalization is futile and may have only worsened drug addiction while maiming millions of lives with prison sentences.

The drug problem needs to be medicalized, which, while increasing the availability of drugs, will also increase treatment and eliminate most crime and imprisonment expense. But the General Assembly isn't considering medicalization. Instead the legislature is giving the impression that the state's salvation lies in taxing potheads and more casino gambling. Even if that could close its budget deficit, what kind of state would this be?

xxx

The big argument for the Connecticut General Assembly's approval of Gov. Dannel Malloy's renomination of Justice Richard Palmer to the state Supreme Court was that judicial independence required it. This was nonsense, a rationale for accepting whatever appellate judges do to rewrite constitutions. The freedom of judges to decide particular cases within established frameworks of the law is one thing. The freedom of judges to rewrite not just the law but constitutions themselves is another, which is what Palmer did in the Supreme Court's decisions on same-sex marriage and capital punishment.

His decision invalidating capital punishment was dishonest, opportunistically misconstruing the legislature's revision of the capital punishment law, which precluded death sentences for future crimes while sustaining pending sentences. Palmer maintained that the legislation signified that the public had turned against capital punishment though the new law was written as it was precisely because the public very much wanted the pending death sentences enforced. Public officials in Connecticut have certain insulation but none is completely above deliberative democracy. Governors and judges can be impeached, legislators expelled, and judges denied reappointment. The legislators who voted against reappointing Justice Palmer had good cause consistent with good constitutional practice.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Anti-marijuana-use poster from 1935.