David Warsh: AI firms and news publishers are dickering over revenue sharing

Baker Library at Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College’s Kiewit Computation Center, cutting edge when it was built, in 1966, and torn down as outdated, in 2018

From Cantor’s Paradise:

“The Dartmouth (College) Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence was a summer workshop widely considered to be the founding moment of artificial intelligence as a field of research. Held for eight weeks in Hanover, New Hampshire in 1956 the conference gathered 20 of the brightest minds in computer- and cognitive science for a workshop dedicated to the conjecture:

"..that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves. We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer."

-- A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (McCarthy et al., 1955)

Somerville, Mass.

Why the speed with which artificial intelligence technologies have been sprung on the world? The answer may have something to do with the model that AI companies have in mind for the most potentially lucrative among their new businesses. Once again it seems to have to do mostly with advertising.

As a result, the newspaper business, broadly defined to include data-base/software businesses such Bloomberg, Reuters and Adobe, is taking stock of itself and its prospects as never before. Readers are learning about the capabilities and limitations of generative artificial intelligence engines, which can produce on demand Wiki-like articles containing detailed but not necessarily dependable information. In the bargain, we may even learn something important about the systems of industrial standards that govern much of our lives.

Those implications emerged from a Financial Times story other week that Google, Microsoft, Adobe and several other AI developers have been meeting with news company executives in recent months to discuss copyright issues involving their AI products, such as search engines, chatbots and image generators, according to several people familiar with the talks.

FT sources said that publishers including News Corp, Axel Springer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and The Guardian have each been in discussions with at least one major tech company. Negotiations remain in their early stages, those involved in them told the FT. Details remain hazy: annual subscriptions ranging from $5 million to $20 million have been discussed, one publisher said.

This much is already clear: Media companies are seeking to avoid compounding the mistakes that allowed Google and Facebook to take over from print, broadcast and cable concerns the lion’s share of the advertising business, in a wave of disruption that began around the start of the 21st Century.

A major problem involves avoiding further concentration among media goliaths. At stake is the privilege of decentralized newspapers, competing among themselves, to remain arbiters of democracies’ provisional truth, the best that can be arrived at quickly, day after day.

Mathais Döpfner. whose Berlin-based media company owns the German tabloid Bild and the broadsheet Die Welt, told FT reporters that an annual agreement for unlimited use of a media company’s content would be a “second best option,” because small regional or local news outlets would find it harder to benefit under such terms. “We need an industry-wide solution,” Döpfner said. “We have to work together on this.”

The background against which such discussions take place is copyright law. Obscured is the role frequently played by privately negotiated industry standards.

Behind the scenes talks will continue. But the changing nature of advertising-based search is a breaking story. Newspapers remain free to take their case to the public, in hopes of government intervention of unspecified sorts.

The adage applies about lessons learned from experience: fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

#David Warsh

#artificial intelligence

David Warsh: The WSJ ‘contains multitudes’

On Chicago’s Lakefront.

— Photo by Alanscottwalker

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

A headline on a story Oct. 21 in the in The Wall Street Journal revealed “Chicago’s Best-Kept Secret: It’s a Salmon Fishing Paradise; Locals crowd into inlets off Lake Michigan to catch fish imported from West Coast to counter effects of invasive species.”

Between vignettes of jubilant fishermen braving the lake-front weather, reporter Joe Barrett offered a concise account of how Great Lakes wildlife managers have coped with successive waves of invasive species over eighty years of globalization. In the beginning were native lake trout, apex predators thriving on shoals of perch. Sea lampreys arrived in the Forties, through the Welland Canal, which connects Lake Ontario with Lake Erie. The blood-sucking eels devastated the trout population, while alewives, another invasive species, grew disproportionately large with no other to prey on them.

Authorities controlled the lampreys with a new pesticide in the mid-Sixties, and imported Coho and later Chinook salmon from the West Coast to rejuvenate sport fishing. Fingerling salmon hatched in downstate Illinois nurseries were released in Chicago harbors, to return to the same waters to spawn at maturity. Meanwhile, ubiquitous European mussels, released from ballast tanks of ships entering the lakes via the St. Lawrence Seaway, improved water clarity, but consumed nutrients needed by small fish. As a native of the region, I remember every wave.

A Coho salmon.

I was struck by the artful sourcing of Barrett’s story. He quoted fishermen Andre Brown, “a 51-year-old electrician from Oak Park;” Martin Arriaga, “a 59-year-old truck driver from the city’s Chinatown neighborhood,” and Blas Escobedo, 56, “a carpet installer from the Humboldt Park neighborhood.”

Providing the narrative were Vic Santucci, Lake Michigan program manager for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, and Sergiusz Jakob Czesny, director of the Lake Michigan Biological Station of the Illinois Natural History Survey and the Prairie Research Institute. The Illinois Department of Health chimed in with its recommendation: PCB concentration in the bigger fish meant no more than one meal a month.

Barrett did not mention the dangerous jumping Asia carp that now threaten to enter Lake Michigan; nor the armadillos, creeping north from Texas into Illinois, with global warming: much less the escalating crime rates in Chicago, which have McDonald’s threatening to move out of the city. But then his was a story about fishery management. And that’s what I like about the WSJ: it contains multitudes.

Earlier last week I had sought to convey to visiting friends the different sensibilities among the newspapers I read. I prize The New York Times for any number of reasons, but its concern for the future of democracy in America often seems overwrought. I look to The Washington Post for editorial balance (never mind the “Democracy Dies in Darkness” motto), and to the Financial Times for sophistication. But it is hard to exaggerate how much I enjoy The Wall Street Journal. I worked there for a time years ago; that surely has something to do with it. But I think it is the receptivity of its news pages I so admire. Like Joe Barrett’s fish story, its sentiments are inclusive. Read it if you have time.

Despites its sale to conservative newspaper baron Rupert Murdoch, the WSJ has preserved the separation between sensible news pages, its worldly cultural and lifestyle coverage, and its fractious editorial pages. Those editorial pages are still recovering from their enthusiasm for Donald Trump, and I sometimes think as I read them that they pose a threat to democracy, if only by their preference for derision. But still I read them, so they must be doing something right.

Barely two weeks remain before the mid-term elections. The races that interest me most are those seeking common ground: Ohio, Alaska, Pennsylvania, and Oregon. There will be time afterwards to sift the results. Is American democracy in danger? I doubt it. E pluribus unum! with a certain amount of thoughtful guidance along the way.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

David Warsh: To come back, print editions of newspapers must solve intricate production problem

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The off-lead story in the Sept. 18 New York Times, illustrated by a fraying American flag, was one of a series: “Democracy Challenged: twin threats to government ideals put America in uncharted territory.” Senior writer David Leonhardt identified two distinct perils: a movement in one major party to refuse to accept election defeat, and a Supreme Court at odds with public opinion. Leonhardt’s argument was well reasoned and deftly written, enough to fill four pages after the jump.

To my mind, though, The Times is overlooking a problem even more fundamental to the conduct of American democracy: the concentration of power in the quartet of daily newspapers that remain at the top of the first-draft-of-history narrative chain. The loss of diversity of news and opinion among metropolitan newspapers in the 50 American states over the last thirty years has not been well understood.

Media proprietor Rupert Murdoch bought The Wall Street Journal from the Bancroft family, in 2007. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post from the Graham family, in 2012. Japanese media group Nikkei acquired the Financial Times from Pearson publishers, in 2015. The New York Times, a fifth-generation family-controlled firm, retains its independence. But Bloomberg LP, an all-digital software analytics and media company, also based in midtown Manhattan, remains looking over its shoulder.

Meanwhile, major metropolitan daily newspapers across the country have been sold and diminished, or collapsed altogether, in the 32 years since the World Wide Web was introduced. These include the Chicago Tribune and its many subsidiaries, among them the Los Angeles Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Hartford Courant and the New York Daily News; The Providence Journal; The Philadelphia Inquirer and 31 other Knight Ridder newspapers, including The Miami Herald and San Jose’s Mercury News; Cleveland’s Plain Dealer, Portland’s Oregonian and New Orleans’s Times-Picayune, among the Newhouse newspaper chain; the Louisville Courier-Journal; the Arizona Republic; Las Vegas Sun, and Dean Singleton’s Denver Post. The Daily Bee, founded in Sacramento in 1857, part of all but the last surviving family-owned newspaper chain, declared bankruptcy in 2020, though the Atlanta Journal-Constitution remains the flagship of Cox Enterprises. Only Texas and Florida maintain several competitive metropolitan newspapers. The Christian Science Monitor ceased publishing a paper edition in 2009, while maintaining a digital presence.

What happened? Google and Facebook entered the advertising business. Antitrust newsletter writer Matt Stoller recently described Google’s rollup of the search-intermediary industry over the course of a decade, notably its 2007 acquisition of DoubleClick, into the voracious advertising sales business that the former “free” search engine enterprise has become. Facebook did much the same. The result was that newspapers lost some 80 percent of their advertising revenues in a decade. More than 2,000 papers went out of business altogether.

In a similar vein, The New Goliaths: How Corporations Use Software to Dominate Industries, Kill Innovation, and Undermine Regulation (Yale, 2022), by James Bessen, makes a compelling case that “dominant firms have used proprietary technology to achieve persistent competitive advantages and persistent market dominance,” by more effectively managing market complexity in industries of all sorts.

Strengthening antitrust enforcement is a good idea, Bessen says, but breaking up firms is unlikely to solve the “superstar problem.” A more effective solution has to do with opening up access to knowledge, which means addressing ubiquitous intellectual-property bottlenecks. Market-driven unbundling – the process that, in the 1970s, led IBM to open its proprietary software to independent applications, and, in the Oughts, Amazon to make its information technology software available to other vendors on its proprietary servers – offer more promising possibilities, he asserts in a closing chapter. Bessen heads a research initiative at Boston University’s Law School. The New Goliaths is an important book. Let’s hope it get the attention it deserves.

American democracy is not doomed to a future dominated by four or five national newspapers. There is reason to believe that the market for home-delivered newsprint newspapers is much broader than it now seems, though it may take years to revive it. Radio returned to prosperity after television advertising all but destroyed its formerly lucrative advertising business. Newsprint thrived for nearly a hundred years despite the entry of both.

To come back from the online onslaught, however, print newspapers must solve an intricate coordination problem, involving every aspect of the business. These include the cost of newspaper production, from newsprint to software to printing facilities; the riddle of subscription pricing; the restoration of home delivery networks; and the reconstruction of advertising sales. Moreover, the new newsprint goliaths must cooperate with big city dailies seeking to regain market share if the problem is to be solved.

Take, for example, a narrow slice of the cost of production problem: the software that enables editors to simultaneously assemble and publish both print and online content. Dan Froomkin, a former Washington Post columnist, reports in The Washington Monthly, that Amazon’s Bezos, upon acquiring The Post, discovered that the process was wildly inefficient, whereupon he tasked chief information officer Shailesh Prakesh to fix it.

The result: a best-in-class publishing platform, Arc XP, that the Post now uses to publish its own product, and licenses to 2,000 other media and non-media sites. But the license, Froomkin says, is expensive. His suggestion: that Bezos do as Andrew Carnegie did with his libraries more than a century ago, and make Arc XP available free to other newspaper publishers, along with its companion Zeus Technology ad-rendering platform. It is an interesting proposal. So is the multi-state antitrust lawsuit against Google and Facebook, slowly making its way in a U.S. District Court. Meanwhile, the bipartisan Journalism Competition and Preservation bill inched forward last week, when the Judiciary Committee voted 15-7 to send it to the Senate floor

What size might be the market for subscriber-based print, supplemented by traditional advertising? At what annual price? There is simply of no way of telling besides customary trial and error. Let’s hope that the new newsprint goliaths will participate in the learning. True, the four national papers and Bloomberg do a pretty good job of gathering news on their own. But it seems clear that the American democracy functioned better when there were more strong voices scattered across its landscape. It makes sense to search for ways by which those circumstances can be restored – plenty of fodder for future columns.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com.

Editor’s note, a few newspapers, most notably in New England The Boston Globe, now under control of the Boston-based Henry family, still retain much, but far from all, of their former journalistic package.

Llewellyn King: For society’s sake, newspapers, whose work is looted by tech firms, deserve a reprieve

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Newspapers are on death row. The once great provincial newspapers of this country, indeed of many countries, often look like pamphlets. Others have already been executed by the market.

The cause is simple enough: Disrupting technology in the form of the Internet has lured away most of their advertising revenue. To make up the shortfall, publishers have been forced to push up the cover price to astronomical highs, driving away readers.

One city newspaper used to sell 200,000 copies, but now sells less than 30,000 copies. I just bought said paper’s Sunday edition for $5. Newspapering is my lifelong trade and I might be expected to shell out that much for a single copy, but I wouldn’t expect it of the public to pay that — especially for a product that is a sliver of what it once was.

New media are taking on some of the role of the newspapers, but it isn’t the same. Traditionally, newspapers have had the time and other resources to do the job properly; to detach reporters to dig into the murky, or to demystify the complicated; to operate foreign bureaus; and to send writers to the ends of the earth. Also, they have had the space to publish the result.

More, newspapers have had something that radio, television and the Internet outlets haven’t had: durability.

I have a stake in radio and television, yet I still marvel at how newspaper stories endure; how long-lived newspaper coverage is compared with the other forms of media.

I get inquiries about what I wrote years ago. Someone will ask, for example, “Do you remember what you wrote in 1980 about oil supply?”

Newspaper coverage lasts. Nobody has ever asked me about something I said on radio or television more than a few weeks after the broadcast.

I was taken aback when, while I was testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee decades ago, a senator asked me about an article I had written years earlier and forgotten. But he hadn’t and had a copy handy.

There is authority in the written word thay doesn’t extend to the broadcast word, and maybe not to the virtual word on the Internet in promising new forms of media like Axios.

If publishing were just another business – and it is a business — and it had reached the end of the line, like the telegram, I would say, “Out with the old and in with the new.” But when it comes to newspapers, it has yet to be proven that the new is doing the job once done by the old or if it can; if it can achieve durability and write the first page of history.

Since the first broadcasts, newspapers have been the feedstock of radio and television, whether in a small town or in a great metropolis. Television and radio have fed off the work of newspapers. Only occasionally is the flow reversed.

The Economist magazine asks whether Russians would have supported President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine if they had had a free media and could have known what was going on; or whether the spread of COVID in China would have been so complete if free media had reported on it early, in the first throes of the pandemic?

The plight of the newspapers should be especially concerning at a time when we see democracy wobbling in many countries, and there are those who would shove it off-kilter even in the United States.

There are no easy ways to subsidize newspapers without taking away their independence and turning them into captive organs. Only one springs to mind, and that is the subsidy that the British press and wire services enjoyed for decades. It was a special, reduced cable rate for transmitting news, known as Commonwealth Cable Rate. It was a subsidy but a hands-off one.

Commonwealth Cable Rate was so effective that all American publications found ways to use it and enjoy the subsidy.

United Press International created a subsidiary, British United Press, which flowed huge volumes of cable traffic through London.

Time Inc. had a system in which their cable traffic was channeled through Montreal to take advantage of the exceptionally low, special rates in the British Commonwealth.

That is the kind of subsidy that newspapers might need. Of course, best of all, would be for the mighty tech companies to pay for the news they purloin and distribute; for the aggregators to respect the copyrights of the creators of the material they flash around the globe. That alone might save the newspapers, our endangered guardians.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Olivia Snow Smith: How Wall Street is killing the newspaper business

Via OtherWords.org

Though lacking the size and prestige of The New York Times or The Washington Post, The Storm Lake Times is very important to its readers.

Two years ago, the small, bi-weekly Iowa paper (circulation: 3,000) won the coveted Pulitzer Prize for taking on agricultural water pollution in the state. If it weren’t for vibrant local papers, stories like these might never come to light.

Unfortunately, all over the country, private equity and hedge funds have been scooping up these cash-strapped papers — and looting them into irrelevance or bankruptcy.

Here’s how it works.

Investors put down a fraction of the purchase price and borrow the rest — and then saddle the company with that debt. Layoffs and cutbacks follow, which leads to a shabbier product. Circulation and revenue decline, then more cuts, and the cycle accelerates.

Eventually the paper is a shadow of its former self, or turned to ashes completely. Wall Street wins, the public loses.

Perhaps the most infamous recent example was the breakdown of the 127-year-old Denver Post. Since private equity firm Alden Global acquired the paper, it has cut two out of every three staff positions — twice the industry rate for downsizing.

To add insult to injury, the firm has been using staff pension funds as its own personal piggy bank. In total, they’ve moved nearly $250 million into investment accounts in the Cayman Islands.

Employees who remain grapple with censorship. Last April, Dave Krieger — editorial page editor of Alden’s Boulder Daily Camera — was fired after self-publishing an opinion piece headlined “Private Equity Owners Endanger Daily Camera’s Future.”

In solidarity, Denver Post editorial page editor Chuck Plunkett resigned, complaining that his publishers were also censoring stories that might offend Alden.

Alden’s Digital First Media runs many other big papers, putting hundreds of newsroom staff at risk of censorship and layoffs. Millions of readers, in turn, may learn only what Alden deems fit for them.

It’s not a new pattern. In 2008, a year after billionaire Sam Zell bought the Tribune Co. — publisher of the Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and other venerable publications — the company filed for bankruptcy, saddled with $13 billion in debt in what’s been called “the deal from hell.”

After it emerged from bankruptcy, the company was left in the hands of — you guessed it — private equity.

The march of these buyout barons continues. This summer, New Media Investment Group (owner of GateHouse Media) announced plans to buy Gannett. The $1.38 billion deal would unite one-sixth of all daily newspapers across the country, affecting 9 million print readers.

New Media anticipates cutting $300 million in costs each year, suggesting layoffs comparable to those at The Denver Post are in the offing — even as the company and its investor owners harvest profits.

This is a crisis. This country lost more than a fifth of its local newspapers between 2004 and 2018, while newspapers lost almost half of their newsroom employees between 2008 and 2018.

A few lawmakers are catching on.

Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) recently introduced the Stop Wall Street Looting Act to curb these abuses, with Warren specifically calling out private equity firms for decimating local newspapers.

Sen. Bernie Sanders recently introduced an ambitious plan of his own, calling for a moratorium on major media mergers and encouraging newsrooms to unionize nationwide.

Newspapers have been critical to American democracy since its founding. By allowing huge corporations to gut newspapers in the name of making a buck, we’re putting a price tag on that democracy when we need it most.

Olivia Snow Smith works for Take On Wall Street. This op-ed was adapted from TakeOnWallSt.com and distributed by OtherWords.org.

Llewellyn King: Do you want an algorithm telling you what to read?

— Photo by Florian Plag

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Old friends from The Washington Post in the 1970s write to me, agonizing over where journalism is headed.

There is no shortage of news or need for news, but there is a desperate need to find new platforms to carry it forward.

There are three existential crises facing the news trade:

· How to finance newspapers.

· How to deal with the power of the technological behemoths, such as Google.

· How to keep a flow of talent into the business while it sorts itself out.

Journalism has always been financed through a kind of subsidy provided by advertising. It has worked well enough, and sometimes enormously well. No one saw a day when the advertising would flee to a cheaper delivery system: the Internet. But it did.

There were intimations of the vulnerability of the setup. Originally, afternoon newspapers were dominant: Go off work, go home and read the paper before bed. H.L. Mencken warned that morning newspapers, such as his Baltimore Sun, would perish.

Instead of Mencken’s prophecy, the playing field tipped the other way. Morning newspapers survived and, one by one, the afternoons failed across the country and the world. Television was the culprit.

In magazines, the television slaughter was more terrible and more complete. Great institutions, keepers of the culture, were swept away: Life, Look, Collier’s and, saddest of all, The Saturday Evening Post. What had been citadels of power and wealth were toppled, not just in America but worldwide: Picture Post in Britain and Outspan in South Africa. All gone.

Newspapers and magazines are embracing the electronic future by becoming electronic platforms, old dogs doing new tricks. Also, the consumer is carrying much more of the cost of production. Newspapers selling for over $2? Unheard of a short while ago.

I was part of discussions in The Washington Post, where we turned down a cover price increase of a nickel, to 15 cents. “The public’s right to know,” it was reasoned, outplayed our financial gain. We were, so to speak, rich enough and could not see that changing.

Still there is no clear way ahead as to how to finance the new reality for newspapers. Some -- the big ones -- will prosper behind paywalls, but most are still looking for a solution. There is talk of subsidies, and there are pure Web platforms that seek contributions: journalism as charity case.

There are hints as to the future here with paywalls and reader contributions, but these alone do not suggest a robust new business model.

The second existential threat is the new delivery systems. If Facebook and Google are to censure content – say, hate speech -- they have moved the whole journalist enterprise to a new and dangerous place: The global behemoths deciding what should and should not be read.

Do you want a faceless algorithm deciding what you can read?

To me this is the greatest threat to journalism and the democracies it protects. Other ways exist, and new ones could be developed, such as libel laws and penalties for criminal mischief.

The great Internet companies should remain what they are in reality: common carriers. If they become censors, freedom of the media is at stake. Virtuous censorship is still censorship and that is, by definition, without virtue.

Finally wages in journalism, except for a few employed by the television networks (themselves seeing the beginning of the end of the monopolies), are at a low point. Freelancing is worse off.

If improvement do not occur, the best minds coming out of the colleges will not go into journalism, they will go elsewhere, often law. Going forward journalism will not solve its problems without a decent flow of talent, and public will not be served either.

I can speak to this. hreporting, and though they had studied it, they would go into law. They did not fancy a life of poverty. Their gain, our serious loss.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

Post-newspaper news-gathering

An advertisement in 1896 for The Boston Globe.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Local newspapers continue to shrink and disappear (the Trump administration’s recent lowering of its very high tariffs on Canadian newsprint might provide a small reprieve). This has encouraged an increase in costly local corruption as the ranks of reporters rapidly diminish as does local civic engagement; newspapers have long been important parts of the public square, acting as crucial sources of laboriously collected and edited information and as convenors for public discussions of important issues.

With the monopolistic Facebook and Google draining away ad revenue, things probably won’t get better for news on paper, unless the Feds start enforcing antitrust laws for a change.

Otis White, the president of Civic Strategies Inc., writing in Governing.com, reports on a very well run community – Decatur, Ga., an Atlanta suburb – where local leaders are trying to fill the civics-knowledge gap, albeit imperfectly. The City of Decatur mails out a monthly newsletter called Decatur Focus updating stuff going on in city government. It’s well done but in effect promotes the interests and status of city officials, elected and otherwise. Decatur also has a program called Decatur 101, which seeks to develop informed and involved citizens. And there’s its Citizens Police Academy, which focuses on how the police department enforces laws.

All very nice, but all communities need independent, private-sector news gatherers. Their demise is jeopardizing local democracy. To read Mr. White’s piece, please hit this link.

Chris Powell: As civic life and local news media decline, why keep slogging on?

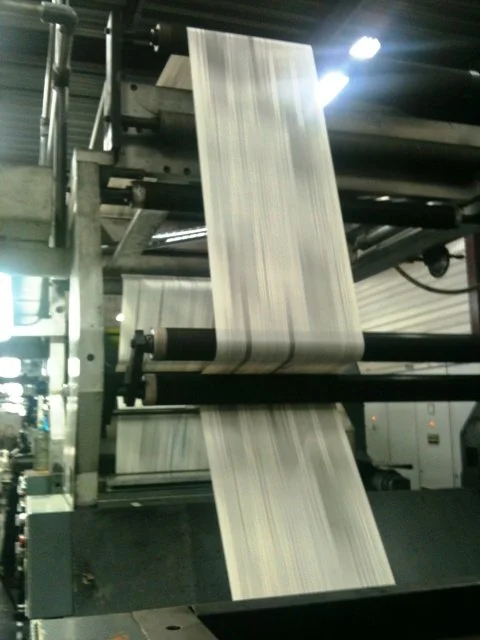

How many more press runs?

When the Journal Inquirer, of Manchester, Conn., merged the weekly newspapers in Rockville, South Windsor, and East Windsor, Conn., and went daily in August 1968, its premise, like the premises of the Connecticut newspapers that had been started long before, was that people wanted local news. The Hartford newspapers serving the growing suburbs to the north and east were not providing much of it. For 25 years the upstart's circulation grew steadily and two of its competitors closed, in large part because they lacked local news.

Back then Connecticut, literate and prosperous, had the highest per-capita newspaper readership in the country. But for most of the last 25 years newspaper circulation throughout the country and in Connecticut has declined, even for the most local of papers.

This is commonly blamed on the rise of the Internet, but recent surveys suggest it is something else. They find that most people are not using the Internet much to obtain local and state news, that most of the news sought on the Internet is national and world news, that there isn't so much interest even in that news, and that most use of the internet is not for news but for social contact, shopping, and amusement.

While newspapers and their internet sites remain the primary providers of local and state news, it seems that interest in such news has collapsed.

Indeed, the collapse of interest in local and state news may correlate less with the rise of the Internet than with the collapse of civic engagement generally as indicated by measures like voter participation.

Census and voter registration figures suggest that even in Connecticut about 25 percent of the eligible adult population doesn't even register to vote. As a result, actual voter participation is probably only 50 percent of the eligible population for presidential elections, a third for state elections, and around 10 percent for municipal elections.

For example, far more people voted in Manchester's town election in 1962 than in its town election in 2017, though the town's population is 40 percent larger.

That is, newspaper readership, like voter participation, is mainly a matter of demographics. The more literate, self-sufficient, and engaged with public life people are, the more they read newspapers. The less literate, self-sufficient, and engaged with public life people are, the less they read newspapers -- and the demographics of Connecticut and the whole country are declining fast.

No one needs newspapers for keeping up with the Kardashians.

Trouble for newspapers is not the worst of it. Democracy and the country are in jeopardy.

So someone who has spent 50 years at a newspaper in Connecticut may be permitted his discouragement. The civic engagement business was never lucrative, but now nearly all local- and state-oriented newspapers struggle to survive.

As the state's economic and demographic decline accelerates, knowledge of Connecticut's past, present, and public policy has lost all financial value except for those who would use it to extract the last scraps of patronage and graft from the state's hapless and insolvent government.

Of course many lives are always wasted, but what kind of future awaits Connecticut when most of its high school graduates never master high school English and math, much public college instruction is remedial, and most people cannot identify the state's three branches of government? (You know -- the teacher unions, the lawyers, and the liquor stores.) Maybe Dire Straits was right:

I shudda learned to play the guitar.

I shudda learned to play them drums. ...

Maybe get a blister on your little finger.

Maybe get a blister on your thumb.

Some pensioners wear T-shirts inscribed: "I'm retired. Having fun is my job." They may have earned their fun, and old folks remain the best newspaper readers, but how much attention are even they paying to Connecticut these days, especially since so many of them are moving to warmer and less-taxed jurisdictions, as even the state's most recent former governor has done?

While everyone of a certain age is entitled to a little time out of the winter cold, for a former governor to leave the state is also demoralizing, and a warning too.

For many state residents have nowhere else to go, nor, as Bing Crosby and Judy Garland sang, do they want to abandon Connecticut despite the damage being done to it:

Circled the globe dozens of times.

Seen all its wonders, known all its climes.

I've searched it with a fine-tooth comb

And found that I only have one home, sweet home.

Connecticut always will be my home.

Still, after so much time in the news business it can be difficult not to view much of what is reported as trivial or a cliche, as T.S. Eliot did even before the era of "weather every 10 seconds."

You will see me any morning in the park

Reading the comics and the sporting page.

Particularly I remark:

An English countess goes upon the stage,

A Greek was murdered at a Polish dance,

Another bank defaulter has confessed.

Of course while the news is repetitive it is not all trivial to the people directly involved, and it usually involves different people, who make it new, though they may no longer care as much about appearing in print as they care about appearing on "social media," where news tends to be less about wars and rumors of wars than boyfriends, girlfriends, relatives, and pets.

So what is the point of staying in the newspaper business? Maybe only spite. It might be hard to let certain people in what is left of the state's public life think that no one was on to them.

Fare thee well now.

Let your life proceed by its own design.

Nothing to tell now.

Let the words be yours. I'm done with mine.

Chris Powell will retire Monday as managing editor of the Journal Inquirer in Manchester. He plans to continue writing columns for Connecticut newspapers and New England Diary.

-

Chris Powell: The decline of civic engagement and newspapers

What happens to local news when there are no local news organizations? What happens to communities without local news? The Washington Post tried to answer those questions the other day, using as an example East Palo Alto, Calif., where many news organizations are nearby but none pays attention to the town.

Interesting as the Post's report was, the answers to its questions were a bit obvious: that without local news, communities stay ignorant of themselves; government decisions are made with less participation; problems are not well communicated; corruption increases; and communities lose their identity.

A related question may be more important: What is behind the decline of local news? The decline is manifested by the fall of newspaper circulation, the closing of scores of dailies and weeklies, and the collapse of newspaper employment by more than half since 2001.

The easy answer is the Internet. But while the Internet competes with newspapers for people's time, as radio and television did, it seldom provides local news. Instead the internet enables people to engage in virtual communities, to immerse themselves in interests that may span the nation or even the world -- sports teams, the stock market, movies, and such -- but at the expense of the attention people pay to their geographic communities.

Most of what remains of local news is still produced by newspapers, and the few Internet sites carrying local news are supported mainly by charitable donations because local businesses don't find internet advertising effective.

The real problem with the decline of local news, as that Washington Post story implied, is demographics. While East Palo Alto, a working-class town with a heavily minority population, lacks local news coverage, its wealthy neighbor, Palo Alto, receives plenty of coverage from local dailies and weeklies.

For Palo Alto's median household income is three times higher than East Palo Alto's, and local news is the most expensive part of journalism, since, while important locally, it is potentially of interest to fewer people than national and world news. Even the most compelling local news story may induce only a few thousand people to pay something for it, while millions of people may pay something for the most compelling national or world news story.

So while struggling communities need local journalism more, they can afford it less -- and they have less interest in it, for their residents are less literate and involved.

Indeed, the decline of local newspapers may correspond less with the rise of the internet than with the collapse of civic engagement as measured by voting in elections, which has been diminishing steadily for half a century. Today even in Connecticut a quarter or more of the population doesn't register to vote.

In a lecture a week ago in his hometown of Winsted, Conn., the country's foremost civic activist, Ralph Nader, noted that most schools fail to teach civic engagement and critical thinking.

Sometimes it's hard to see what the schools are teaching at all, especially when the annual National Assessment of Educational Progress tests show that even in Connecticut most high school seniors never master high school math or English. Such students are not prepared to become newspaper readers, much less citizens.

In the end communities will get local news only if they are willing and able to pay for it and value civic engagement. As public policy keeps dumbing down and impoverishing Connecticut and the country, demographic trends are otherwise.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Newspapers' publicly held problem

I write as someone who worked for several newspapers in a 43-year career in that business , as a finance editor at three of them and whose generally Republican family was in the business world (no dreamy eyed professors or liberal social reformers in my upbringing).

There's been much incomplete reporting on the implosion of the newspaper business, whose crisis poses grave threats to the knowledge and civic engagement of citizenry. Indeed, the general level of ignorance seems to rise every year commensurate with the accelerating move of life onto the Internet.

The Internet has long and glibly been cited as virtually the only reason for the sector's decline. But in fact, business reporters (they fear antagonizing their bosses) generally fail to note the huge and destructive impact (to journalism anyway) of public ownership.

Most newspapers used to be closely held, often family held, enterprises. Their owners, of course, wanted to make a good profit, and in fact dominant newspapers in their areas generally made a very good profit. Historically, the best metropolitan papers, with high journalistic ambitions, made about a 10-15 percent profit margin -- more than the average of the margins of companies listed on the S&P 500 Index. But the owners tended to want more than just money (unlike, mostly, now). They wanted influence and many even had altruistic aims -- improving their communities, etc.

But, accelerating in the '90s, came the sale of these companies at big prices to publicly held enterprises listed on stock exchanges. Wall Street took over from civic concerns. With the pressure to please the stock analysts, and enrich themselves, senior execs (who also had a lot of stock in their companies) of the new owning companies pushed for ever-higher profit margins -- to astronomical levels of 30 percent or more. Meanwhile, they had to worry about paying off the debt incurred to buy the newspaper companies.

So for years they did not reinvest in their properties, but rather laid off as many employees as they could, and made other cuts, to keep the profit margin (and thus capital gains, dividends and senior execs' salaries) as high as possible. The emphasis was on meeting targets for the next quarter, and not building for the long term. Take the money and run.

As always in business, there were some notable exceptions to this money-only culture and I was fortunate to work for a couple of them. My last boss, for example, Howard Sutton, of The Providence Journal, spent innumerable hours (much of it anonymously) working for the betterment of his community.

Since a lot of these newspapers were well entrenched as virtual monopolies in their areas, this worked for a while -- until the papers were so hollowed out that their decline was probably irreversible (though the senior execs and their pals on their boards continued to pay themselves gargantuan compensation for many years as all this went on).

Indeed, the intensity of shareowners'/execs' thirst for huge and immediate payouts seems to swell every year. I am as greedy as the next fellow, and firmly believe in capitalism and its creativity, but I've been astonished by the surge in senior executive pay since I worked in Lower Manhattan at The Wall Street Journal in the '70s.

Meanwhile, in the early and '90s, the execs made the catastrophic decision as the World Wide Web got rolling to put the journalism on papers' Web sites for free, thus encouraging many readers to cancel their paid subscriptions to the paper version (whence came and still comes most of the revenue). The magical thinking was that the new ad revenue on their Web sites would make up for the loss of revenue from readers' subscriptions.

In fact, Web sites are generally lousy places for most ads, especially display ads. Those reading news media on screens, unlike folks browsing through a newspaper, are generally irritated by ads. (The "X'' button to close the ads gets intense use!)

There was no display-ad bonanza. And the likes of Craig's List swiped the vast and easy money from classified ads. The Internet is great for classified ads.

And by offering all this information, collected by hardworking reporters and processed by hardworking editors, for free, the newspapers were in effect telling their readers what they thought the stuff was worth. Bad marketing!

The Internet has posed big challenges to newspapers, but that's only part of the story. Meanwhile, those old-fashioned press lords of family own companies look good. They were in it for the money, but for other things, too.

-- Robert Whitcomb