Philip K. Howard: A way to make Biden infrastructure program work as hoped

Construction crew laying down asphalt over fiber-optic trench, in New York City

— Photo by Stealth Communications

The Bourne Bridge and the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge at sunset. The Bourne Bridge, at the canal’s western side, and the Sagamore Bridge, to the east, both built in the Thirties, are slated to be replaced.

President Biden’s breathtaking $5 trillion infrastructure agenda — about $50,000 in debt for each American family — is stalling on broad skepticism on both the goals and means of spending that money. There’s bipartisan agreement on at least some of the goals: Spending $1.2 trillion to fix roads, build new transmission lines, expand broadband, and provide clean water could improve American competitiveness as well as its environmental sustainability.

There’s a deal to be made here: Use this moment to overhaul how Washington spends money. Skeptics are correct that, otherwise, most of the money will go up in smoke. What’s needed is a new set of spending principles, based on the principle of commercial reasonableness, enforced by a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board.

The key to governing is implementation. Big talk in press conferences rarely results in success. Nor does throwing money at a problem. The chaos in Afghanistan reveals what happens when top-down dictates are not accompanied by a practical plan for executing the goal. But the Biden administration has no plan on how to implement its infrastructure proposals wisely.

What is certain is that, without reform, most of the infrastructure money will be wasted. Red tape, delays, rigid contracting rules, entitlements and other inefficiencies guarantee that American taxpayers will receive less than 50 cents of infrastructure value for each dollar. That’s optimistic. Comparative studies of infrastructure costs in developed countries show that public transit in the U.S. can be four times as expensive as in, say, Spain or France. A highway viaduct in Seattle cost three times more than a comparable project in France, and seven times more than one in Spain.

What causes the waste? No U.S. official has authority to use commonsense, at any point in the process, to build infrastructure sensibly. Other countries have “state capacity”— a euphemism for public departments where officials are given the authority to make contract and other decisions comparable to their counterparts in the private sector. In America, by contrast, officials’ responsibility is preempted by red tape.

Here are some of the main drivers of waste:

- Permitting can take years because no official has authority to 1) limit environmental reviews to important impacts; 2) resolve disagreements among competing agencies; or 3) expedite resolution of lawsuits. In our study Two Years, Not Ten Years we found that delay alone can more than double the effective cost of projects.

- Rigid procurement protocols strive to detail each nut and bolt in advance, limiting the flexibility needed to confront unanticipated issues inherent in any complex construction project. This leads to massive waste as well as costly change orders.

- Union collective-bargaining entitlements have accumulated over the decades, for example, requiring twice as many workers as needed to operate the tunneling machine for a New York subway. Work rules are designed not for safety or efficiency, but to provide compensation even where there’s no work.

- Legislative mandates further increase the cost of public projects. The “Buy American” laws can increase costs by 25 percent, sometimes more. The Davis-Bacon Act from 1931 increases labor costs by upwards of 20% over market by requiring “prevailing wages”— which is a euphemism for highest wage that can be justified. An army of Washington bureaucrats has the job of dictating wage rates and benefit packages in hundreds of construction job categories in each of 3,000 designated labor markets in the U.S.

- All these legal processes, rigidities and entitlements provide grounds for a lawsuit for any unhappy bidder, contractor, labor union, or environmental group. Lawsuits not only add costs to delay projects, but are commonly used as a weapon to extract payments and concessions that further raise the costs.

Thick rulebooks have supplanted human responsibility. Washington allocates money, with lots of legal strings. It then gives grants to states and localities, many of which are actuarily insolvent – precisely because they cannot manage their public unions and other interest groups. Time passes. Lawyers and consultants produce environmental impact statements. Various groups object and threaten lawsuits. Unions demand ever-greater benefits. Understaffed civil servants try to write procurement guidelines that anticipate every detail and eventuality. The low bidder wins, even if the bidder has a lousy record. Some infrastructure gets built, often badly, and always at a cost that far exceeds what a commercial builder would have paid. The waste here is a scandal — political leaders might as well take taxpayer money and throw it in the fireplace.

How should infrastructure be built? What causes waste in building infrastructure, as NYU’s Alon Levy puts it, is “rigid[ity], where what is needed is flexibility and empowerment” of officials with responsibility. Someone needs to be in charge of each project, and whoever’s in charge needs to have the flexibility to negotiate contracts, adapt to new conditions, and, above all, not to be hamstrung by unrelated requirements.

Building roads, bridges and power lines isn’t rocket science. Other countries and private companies know how to do this. Most public engineers know what performance standards are required. By the simple mechanism of empowering public servants to take responsibility, Levy found, other countries are able to “spend a fraction of what the US does on the same bridge or tunnel.”

Giving officials flexibility to use their judgment, however, requires a mechanism to overcome Americans’ distrust of government. That’s what keeps America’s byzantine bureaucracy in place. Any effort at reform is resisted by groups who argue “What if... an official is on the take?” “What if…the official is Robert Moses, and wants to bulldoze poor communities?”

Opponents to spending reform are mobilizing as I write. The $1.2 trillion Senate bill includes permitting reforms that seek to limit the permitting process to two years. But even this modest reform is under attack by “environmental justice” groups who argue that two years is insufficient to consider those issues. Similarly, a reform to expedite permits for interstate transmission lines is being vigorously opposed by the state energy regulators. They pluck the strings of distrust. But their real objection is that minimizing delay removes the legal veto which they use to extract lucrative benefits for themselves.

What’s needed to overcome distrust is a nonpartisan oversight body that is empowered to avoid waste and corruption. In other developed countries, most citizens accept official authority. But Americans don’t. Creating a trusted oversight institution means it can’t be in the control of either political party. An example are the nonpartisan “base-closing commissions” which decide which defense bases should be shuttered.

I propose a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board, analogous to oversight boards in Australia and other countries. Its responsibilities would be not to build infrastructure but to oversee and report on how infrastructure is built. Funding could still go through states, but only on condition that timelines and contracts meet standards of commercial reasonableness. No more featherbedding. No more payoffs. States would lose funding if they continued current practices.

The power of a trusted oversight body is exponentially greater than its size. The availability of accountability, not micromanagement, is the element that avoids waste while instilling trust and confidence that everyone is doing their part.

America is at an institutional crossroads. Nothing much works as it should because no official, or teacher, or hospital administrator, or manager, is authorized to make sensible choices. Pruning the jungle of red tape never works because the underlying premise is to avoid human judgment on the spot. The only solution is to replace the jungle with a simpler framework activated by human responsibility and accountability. But who will oversee those officials? That’s why a trusted oversight body is essential.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, author and chairman of Common Good, a bipartisan reform coalition. This piece first ran in The Hill.

James T. Brett: Infrastructure bill would be a boon for New England

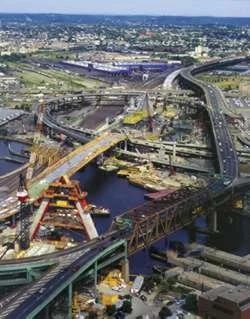

Work underway during “The Big Dig,’’ in Boston (1991-2106), New England’s most dramatic local infrastructure project so far.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

With billions of dollars of federal relief authorized over the past 18 months, and more and more Americans receiving vaccinations each day, our economy is gradually inching closer to recovery. However, there is more left to do. The New England Council believes that passing a robust infrastructure package will help meet numerous and long-standing unmet demands, and will help our region’s businesses remain competitive and allow our residents to thrive.

As New Englanders, we know all too well the infrastructure challenges that our region faces. Too many of our bridges are structurally deficient and yearly increases in the number of vehicles and drivers have put more stress on our roadways. A growing number of residents across our region are looking to transit to provide a safe, affordable and reliable means of transportation. Besides the need to meet new requirements for a growing region, our aging water systems – some approaching or surpassing a century old – need attention. And the pandemic has shown that broadband is a critical need for New England to expand telework, telehealth and remote learning options. These and many other needs must be addressed.

Just months ago, a bipartisan group of senators and President Biden agreed upon a bold infrastructure framework This five-year deal would fund so-called “traditional” infrastructure – roads, bridges, rail, transit, ports and airports and water systems. In addition, the deal called for new infrastructure spending which would be allocated towards those traditional infrastructure items along with an expanded list of core infrastructure such as broadband, resiliency, and electric-vehicle infrastructure.

As for financing the new spending, the agreement called for more than a dozen ways to do so, including redirecting unused unemployment insurance payments; re-purposing certain unspent COVID-19 relief funds; extending customs fees; reinstating certain Superfund fees, and selling off telecom spectrum to name a few.

In late July, senators reached a final deal on legislation to enact the bipartisan agreement. Besides baseline funding, some $550 billion in new spending over the next five years was included, representing a compromise backed by members of both parties. The bill included a number of the “pay-fors” from the original agreement as well as new funding sources designed to maximize support among the members of the Senate. The Senate legislation also included other crucial infrastructure priorities for our region, like addressing PFAS contamination.

The hard work of the Senate paid off. On Aug. 10, this legislation – the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act – was adopted by a bipartisan vote of 69 to 30. Every senator from New England voted in favor.

Now, the bill is before the U.S. House of Representatives, and a vote is slated to be held before the end of this month.

Not since the Eisenhower administration has Congress had such an opportunity to advance a package that will so boldly affect infrastructure in a manner that will benefit virtually every individual in New England and across the nation. The New England Council believes that this landmark legislation would have a tremendous impact on our region by addressing many of the challenges we face, while also creating new jobs and spurring economic growth. We are grateful to the Senate for taking quick action on the bill, and we urge the House to follow suit as soon as possible.

James T. Brett is president and chief executive of The New England Council.

Philip K. Howard: Fighting a pandemic in red-tape nation

— Photo buy Jarek Tuszyński

America’s current crisis reveals the paralytic nature of its regulatory order.

America failed to contain COVID-19 because, in part, public-health officials in Seattle were forced to wait for weeks for bureaucratic approvals intended—ironically—to avoid mistakes. Now that the virus is everywhere, governors and President Trump have tossed rulebooks to the winds. It would otherwise be illegal to do much of what we’re doing—setting up temporary hospitals, organizing mass testing, buying products and services from noncertified providers, practicing telemedicine, using whatever disinfectant is handy . . . without documenting and getting preapprovals for each step.

America will get past this health crisis, thanks to the heroic, unimpeded dedication of health-care professionals. But what will save America from a prolonged recession? Many shops and restaurants will be out of business. Dormant factories and service organizations will need inspections before reopening. Schools and other social services will have to restart, with personnel changes and new needs that cannot be anticipated. Government agencies will be overwhelmed by requests for permits. Lawyers will present corporate clients with exhausting legal checklists. Lawsuits will be everywhere. Months, perhaps years, will pass as America tries to restart its economic engine while bogged down in bureaucratic and legal quicksand.

We need an immediate intervention to break America free from its bureaucratic addiction. It must be done if the nation is to come back whole in any reasonable time frame. The first step is for Congress to authorize a temporary Recovery Authority with the mandate to expedite private and public initiatives, including the waiver of rules and procedures that impede public goals. States, too, should set up recovery authorities to expedite permitting and waive costly reporting requirements.

Aside from broad goals, most regulatory codes don’t reflect a coherent governing vision. All these regulations just grew, one on top of the other, as successive generations of regulators thought of ways to tell people how to do things. Getting America up and running requires the ability to cut through all this red tape quickly. A Recovery Authority could expedite productive activity in many areas.

The U.S. ranks 55th in World Bank rankings for “ease of starting a business”—behind Albania and just ahead of Niger. The main hurdles are regulatory micromanagement and balkanization. You don’t get a permit from the “government” but from many different agencies, sometimes with contradictory requirements. Mayor Michael Bloomberg discovered that starting a restaurant in New York City required approvals from up to 11 agencies.

State recovery authorities could expedite permitting by creating “one-stop shops” such as those that operate in other countries. The lead agency would be given authority to waive rules and procedures not necessary to safeguard the broad public interest. Instead of waiting months, or longer, until inspectors can make site visits to verify compliance, the lead agency would have authority to grant permits, subject to later inspection.

To stimulate the economy, President Trump has floated the idea of a $2 trillion infrastructure plan. A big infrastructure buildout was promised as part of the 2009 stimulus as well—five years later, a grand total of 3.6 percent of the stimulus had been spent on transportation infrastructure. That’s because, as then-President Obama put it, “there’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”

Bureaucratic delay is ruinously expensive. In a 2015 report, “Two Years Not Ten Years,” I found that a six-year delay in infrastructure permitting, compared with the timeline in other countries, more than doubles the effective cost of infrastructure projects. I also found that lengthy environmental review is usually harmful to the environment, by prolonging polluting bottlenecks. Work rules and other bureaucratic constraints precluding efficient management multiply the waste of public funds. The Second Avenue subway, in New York City, cost $2.5 billion per mile; a similar tunnel in Paris, using similar machinery, cost about one-fifth as much.

The Recovery Authority could get people working immediately, and double our bang for the buck, by giving one federal agency authority (in most cases, the Council on Environmental Quality) the presumptive power to determine the scope of environmental review, focusing on material impacts; granting the Office of Management and Budget presumptive authority to resolve disagreements among agencies; and requiring that New York State and other recipients of federal funding waive work rules not consistent with accepted commercial practices.

Schools have become hornets’ nests of red tape and legal disputes. Reporting requirements weigh down administrators and teachers with paperwork. More than 20 states now have more noninstructional personnel than teachers—mainly to manage compliance and paperwork. Rigid teaching protocols and metrics cause teachers to burn out and quit. Almost any disagreement—with a parent over discipline, with a teacher or custodian over performance—can result in a legal proceeding, further diverting educators from doing their jobs. Federal mandates skew education budgets without balancing the needs of all the students. Special-education mandates now consume a third or more of some school budgets—much of it through obsessive bureaucratic documentation.

Getting schools restarted could easily get bogged down in bureaucratic requirements and defensive legal contortions. The Recovery Authority could replace reporting requirements with evaluations of actual performance. It could also replace entitlements with principles that allow balancing the interests of all students, and formal dispute mechanisms with informal, site-based review by parent-teacher committees.

The Recovery Authority should look at health-care innovations and waivers that have worked throughout the coronavirus crisis—such as telemedicine—and continue these practices, beyond the recovery period.

The federal Recovery Authority should aim to liberate initiative at all levels of society while honoring the goals of regulatory oversight. It should not be part of the executive branch, but rather, established along the same lines as independent base-closing commissions. For waivers of regulations and all other actions consistent with underlying statutes, the executive branch would be authorized to act on recommendations within the scope of the Recovery Authority’s mandate. For statutory mandates, Congress should explicitly provide temporary waiver authorization to permit balancing and accommodations.

Every president since Jimmy Carter has campaigned on a promise to rein in red tape. Instead, it’s gotten worse because no one has thought to question the underlying premise of thousand-page rulebooks dictating precisely how to achieve public goals. The mandarins in Washington see law not as a framework that enhances free choice but as an instruction manual that replaces free choice. The simplest decisions—maintaining order in the classroom, getting a permit for a useful project, contracting with a government—require elaborate processes that could take months or years. Essential social interactions—a doctor talking with the family about a sick parent, a supervisor evaluating an employee, a parent allowing children to play alone—are fraught with legal peril. Slowly, inexorably, a heavy legal shroud has settled onto the open field of freedom. America’s can-do culture has been supplanted by one of defensiveness.

COVID-19 is the canary in the bureaucratic mine. The toxic atmosphere that silenced common sense here emanates constantly from a governing structure that is designed to preempt human judgment. The theory was to avoid human error. But the effect is to institutionalize failure by barring human responsibility at the point of implementation. It’s as if we cut off everyone’s hands.

Coming out of this crisis, America needs a Recovery Authority to unleash potential across all sectors. Perhaps now is also the moment when Americans pull the scales from their eyes and see our bureaucratic system for what it is—one governed by a philosophy that fails because it doesn’t let people roll up their sleeves and get things done.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, writer, New York civic leader, photographer and founder and chairman of Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left.

Llewellyn King: The Internet of Things will let cities reimagine infrastructure

The new World Trade Center, in Lower Manhattan

Why no jubilation?

You’d have thought the agreement between House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and President Trump to spend $2 trillion on infrastructure would cause wild celebration.

Why, then, didn’t the church bells ring out, the fire boats send arcs of water into the air and the stock of the construction companies, steel producers, asphalt purveyors and paint makers soar? It’s because nobody believed that we have the political coordination -- sometimes expressed as political will -- to do the deed and find the money.

Some money will be found eventually -- after some disaster like the collapse of a bridge on an essential highway, or the failure of one of the critical tunnels under the Hudson River, which carry people and goods up and down the East Coast.

It’s the equivalent of “I’ll mind what I eat after my heart attack” kind of thinking.

The infrastructure from airports to ports, roads to bridges is in parlous shape. We are a first-world nation, with third-world ways of moving ourselves and our goods.

Even if Congress found the money through acceptable taxes (an oxymoron) or acceptable program cuts (another oxymoron), years of squabbling will ensue between the states, between their congressional sponsors, with every locality on bended knee with its begging bowl raised high.

Yet the national infrastructure is due to get a powerful boost not from Washington, but rather from the Internet of Things.

Forces are amassing remake cities, and in so doing to reimagine the infrastructure.

These forces are the companies, academics and visionaries who see a future city where drones will deliver packages, automobiles will connect with each other and eventually will be driverless, as they speed down highways that’ve been modified for them.

WiFi will be available everywhere and traffic will flow better not because of new highways, but because its management will be outsourced to computers which will adjust traffic flows, change lights and direct interconnected cars to take the least-congested route. Think GPS navigation that can control the journey automatically.

Vehicles might suggest a route for you, warn you that the car, two spaces ahead, is weaving or that there’s an impending thunderstorm. This ability of cars and other vehicles to “talk” to each other is known as connectivity. Many of the features of this future conversation between vehicles and their environment are already being built into new cars.

It isn’t in use yet: Your car has a brain waiting to be engaged.

Potholes won’t vanish, but they’ll be identified as soon as they appear and near-automated machines will be dispatched to fill them.

The future of infrastructure is that it’ll be digitally managed to make it more efficient and to predict failures accurately. It won’t build bridges, tunnels, seaports or clear blocked canals. What it may do is move the needle in subtle ways.

More important will be the political impact of the big-company lobbies that will be unleashed across the political spectrum from the White House, to Congress, to the state capitals and the city halls. Big lobbies tend to get their way -- and they will when companies like Amazon, Google, IBM, Verizon, AT&T, Cisco, Uber and Lime are demanding upgrades to the infrastructure to accommodate their digitized world.

At present, infrastructure rejuvenation is a political wish list. Soon it will get teeth, tech teeth.

Most important for the future of cities -- from better lights and first responder systems to automated buses and ride-share vehicles -- will be the sense that things are moving.

History shows us that the public is hungry for the new, less so for repairs. Look at the history of Apple and how product after product, from tablets to phones to watches, has been snatched up. Now think of that hunger applied to a smart city which will have exciting new technology, making them more livable and, hopefully, more lovable.

Think of the coming infrastructure surge as the technological gentrification of cities.

It’s the tech giants and their lobbyists, abetted by public demand, who’ll redirect White House and congressional thinking about infrastructure in a world in which the invisible highways of the Internet will be controlling the old visible and familiar ones.

The Internet controls the vertical and the horizontal, so to speak.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com.

More bridges to nowhere

"The Beauty of Broken Bridges'' (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb

So whatever happened to Trump's promises to start rebuilding America's collapsing infrastructure, which is about the worst in the Developed World?

Philip K. Howard: How to make a deal to address America's infrastructure crisis

A photo by Philip K. Howard in his "Peripheral Visions'' series, much of it about transportation infrastructure, some of it crumbling. To see more, please hit this link.

President Trump this week reiterated his commitment to “rebuild our crumbling infrastructure.” He called upon Congress to enact a law that “generates at least $1.5 trillion” and also to “streamline the permitting and approval process — getting it down to no more than two years, and perhaps even one.”

This would be an enormous boon to society, improving not only America’s competitiveness, but also creating a greener environmental footprint — while adding more than a million new jobs.

But environmental groups are lining up in opposition even before they’ve seen the details. Streamlining red tape, they argue, requires gutting environmental regulations. Are they really in favor of bloated processes that can take a decade or longer and produce impenetrable 5,000-page environmental review statements?

The facts are not on their side. A 2015 report by my organization, Common Good, found the following:

Other greener countries such as Germany approve large projects in less than two years, including environmental review.

A typical six-year delay in large projects more than doubles the effective cost of the projects.

Lengthy environmental reviews often harm the environment by prolonging polluting bottlenecks.

Modernizing America’s infrastructure is a necessity, not an ideology. Rickety transmission lines lose 6 percent of their electricity, the equivalent of 200 coal-burning power plants. About 2,000 “high-hazard” dams are in deficient condition. Century-old water-mains leak over 2 trillion gallons of fresh water a year. Over 3 billion gallons of gasoline are consumed by vehicles idling in traffic jams. Half of fatal car accidents are caused in part by poor road conditions.

Fixing this doesn’t require changing, much less gutting, environmental protections. Common Good has presented Congress with a three-page legislative proposal that creates clear lines of authority to make decisions on a timely basis: An environmental official would be authorized to focus the review on material issues, not thousands of pages of trivial detail; the White House could resolve disagreements among bickering agencies; federal law would preempt delays by state and local governments on interstate projects; and lawsuits would be expedited and limited to material environmental harms, not foot faults.

No one intended environmental review or permitting to take a decade. Current regulations say that analyses in complex projects should not exceed 300 pages. But the review for raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, a project with virtually no environmental impact (it used the existing bridge foundations), was 20,000 pages including exhibits. This is bureaucratic insanity.

What the current process does is give environmental groups a veto. Just by threatening to sue, they can drag processes on for years. But where in the Constitution does it empower naysayers to call the shots? Environmental review should not be used to prevent elected officials from making decisions.

Funding is also obviously needed. The political deal is obvious: Democrats should agree to streamline permitting as long as Republicans provide adequate funding. Most roads and other such projects lack a revenue stream and require public funds. It’s a good investment, returning about $1.50 for every dollar spent, according to Moody’s. It’ll be an even better investment when effective costs are cut in half by streamlining permitting.

Trump’s initiative is a moral as well as a practical imperative. We are living off the infrastructure built by our grandparents and their grandparents. What shape will it be in when we bequeath it to our grandchildren?

New York has choke points that can’t tolerate any further delay. The two rail tunnels coming into Penn Station from New Jersey are over 100 years old, and were badly damaged by Superstorm Sandy. When they shut down for repairs the result is “carmageddon” — 25-mile gridlock.

The approach bridge to those tunnels is made of iron and wood, and occasionally catches fire or gets stuck when pivoting open for barge traffic — causing trains to wait for hours. The “Gateway project” for two new tunnels is essential to avoiding economic and environmental chaos, and almost ready for construction. It needs permits and money. Congress has to provide it.

On fixing America’s transportation woes, it’s time to link arms, not use any pretext to oppose this plan.

Philip K. Howard is chairman of the nonpartisan Common Good (commongood.org) reform organization and a New York-based civic leader, lawyer, author (including the best-selling The Death of Common Sense), and photographer. He's also an old friend, classmate and sometime colleague of New England Diary editor Robert Whitcomb. This piece first ran in The New York Post.

Philip K. Howard: 4 approaches to fixing America's infrastructure

An image from Philip K. Howard's "Peripheral Visions'' photos, which he has taken over the years, especially in cities. This goes along with his public-policy expertise in America's infrastructure, especially regarding transportation.

He says: "These images frame the repetitive patterns of daily landscapes that we feel but rarely consciously observe. Shot on 35mm film at slow shutter speeds to convey how most of us experience these moments, they are impressionistic, with large prints taking on a pointillistic quality.'' Mr. Howard's photos can been seen at philipkingphoto.com.

A new White House office of innovation, led by Jared Kushner, has been created to apply business techniques to make government work better. Leaving aside state enforcement powers, much of what government does is deliver (or subsidize) goods and services. What would have to change to make those government functions more business-like?

Fixing America’s fraying infrastructure, for example, enjoys broad public support. As a builder, President Trump would seem uniquely qualified to oversee this initiative. But government can’t seem to get projects moving. Only 3.6 percent of the $800 billion 2009 stimulus plan was put to use on transportation infrastructure. No one was able to make the needed choices—as President Obama put it, “there’s no such thing as shovel-ready projects.”

How would a business go about fixing America’s infrastructure? It would make choices in four broad categories, none of which Washington will do.

1. Set priorities. Washington has no action plan to rebuild the rickety power grid, or to prioritize interstate bottlenecks. It basically leaves the setting of projects to states and localities—as with the “bridge to nowhere.”

Solution: Put someone in charge of setting national priority projects, which then receive federal support. Australia, for example, has a central committee that receives applications from states and decides which get federal support.

2. Cut red tape. Decade-long review and permitting procedures compromise or kill projects by a) doubling the effective cost, b) creating uncertainty that discourages public and private capital from sponsoring projects, and c) skewing project design toward mollifying whoever threatens to sue. Lengthy environmental review—often thousands of pages of mind-numbing detail—turns out to be harmful to the environment in most cases, because it delays fixing polluting bottlenecks.

Solution: Set deadlines (two years maximum for major projects; six months for fix-it projects), and create clear lines of authority to make needed decisions. Only Congress can do this. Scores of well-meaning laws since the 1960s have resulted in a jumble of competing obligations and balkanized authorities, at the federal, state and local levels.

Clear lines of authority are essential; that’s how greener countries such as Germany are able to approve major projects within a 1-2 year timetable. The nonprofit Common Good, which I chair, has a three-page legislative proposal that: a) gives the chair of the Council of Environmental Quality, who reports to the president, the job of keeping environmental reviews focused on important issues; b) gives the director of the OMB the authority to resolve all interagency disputes and to balance competing regulatory concerns; c) preempts state and local approvals for national projects if their approval processes extend beyond federal timetable, and; d) expedites and limits lawsuits.

3. Outsource design and construction. Most businesses, like government, have no special know-how in large construction projects. Typically, businesses solicit “design-build-maintain” bids which put the contractor on the hook for long-term success of the infrastructure. Government, by contrast, tries to “spec” out every detail in advance—with the predictable result that government fails to anticipate contingencies and ends up paying for costly change-orders and higher maintenance.

Solution: Require best-practices procurement as a condition for federal infrastructure aid. Other countries, such as Australia, make much more use of so-called 3P arrangements (Public-Private partnerships), even in situations where the infrastructure has no revenue stream and the developer is repaid out of general tax revenues. It is generally more cost-effective to let private developers take the risks of the numerous contingencies and to bear the responsibility of maintenance.

4. Don’t be reluctant to invest in good projects. Businesses look at the return on capital invested. By most accounts, the economic benefits of fixing America’s infrastructure are huge—returning $5.20 on each $1 invested in modernizing the Interstate highway system, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. Plus 2 million jobs. Plus a greener footprint.

A business would use whatever financing was available to achieve returns on this level. It would even raise price of products if it thought it customers saw the benefit. If a penny-pinching business let its physical plant deteriorate, to the harm of its customers, it would soon be taken over by someone else. Perhaps that’s what happened in the last election.

Solution: This should be the easiest change, because it requires no legal amendments. The Republicans’ refusal to consider any new revenue streams to fix broken infrastructure is another symptom of its dysfunction. Ask Alexander Hamilton: Raising revenues to invest for the greater good does not violate conservative principles. The decision here could hardly be more obvious: For example, a 25-cent rise in the gas tax, which has stayed at the same level for a quarter century, would finance about half of President Trump’s ten year trillion-dollar initiative.

Washington will resist these changes, because, unlike business, it doesn’t want to make new choices. That requires someone taking responsibility. In Washington, the deck is stacked for the status quo—no new infrastructure without a decade of review, no permit without approval from a dozen agencies, no new taxes even if traffic bottlenecks cost billions. No is everywhere. Maybe no is a good presumption for new laws, but not when government needs to deliver goods and services.

Back in the old days, when Washington leaders worked things out, the deal for an infrastructure initiative would be obvious. Democrats agree to streamline environmental review, and Republicans agree to raise taxes in exchange for a streamlined process that cuts costs in half.

Infrastructure is a kind of canary in the mine of democracy. Everyone says they want infrastructure, but there’s no movement. That’s because dense bureaucracy, by stifling any capacity to deliver projects in a reasonable time frame, has removed the oxygen of democracy. A congressional leader might be more amenable to funding infrastructure if he knows that his district’s stretch of Interstate 80 will get a new lane next year. What Washington needs is what every successful business has: a hierarchy of responsibility that allows responsible people to hammer out accommodations and start making decisions again.

Philip K. Howard is a New York City-based civic leader, author (The Death of Common Sense and The Rule of Nobody among them), lawyer and photographer. He is chairman of Common Good (common good.org), the legal- and regulatory-reform organization.

Philip K. Howard: Blame Congress for our crumbling infrastructure

The infamous Bayonne Bridge.

President Trump has signaled that one of his next big initiatives will be to jump-start a trillion-dollar program to rebuild America's fraying infrastructure. As a former builder, Trump would seem to be uniquely qualified to oversee this initiative.

Rebuilding infrastructure enjoys broad public support, unlike, say, the failed rewrite of Obamacare, The economic benefits will be huge — not only improving America's competitiveness, but returning upwards of $5 on each $1 invested, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. Two million new jobs would be created.

But it's all talk. What's missing is pretty basic: No one has the authority to say Go. Although supposedly in charge of the executive branch, Trump finds himself in a kind of mosh pit of overlapping statutory responsibilities and inconsistent legal mandates.

Approval processes can take a decade or longer. Environmental reviews, meant to highlight important choices, obscure them in thousands of pages of mind-numbing detail.

For projects that survive this gantlet, the delay dramatically increases costs. Uncertainties over time and cost keep many projects on the sidelines.

Governing shouldn't be this hard. Traffic bottlenecks, overflowing wastewater, rickety power grids, and crumbling dams desperately need to be fixed. All that's needed are responsible officials to give permits and allocate funding.

Who's to blame here?

Shine the spotlight on Congress. For 50 years, under Democratic and Republican control alike, Congress has piled up law after law, many with absolute mandates to protect endangered species, preserve historic structures, guarantee access to the disabled and scores of other well-meaning goals.

The accretion of statutes is matched 10:1, more or less, by agency regulations written to implement Congress's mandates. All these laws give enforcement power to 18 or so separate federal agencies — sometimes all on the same project. To top it off, almost anyone can sue based on alleged failure to comply with any of the countless requirements.

It's amazing anything gets built.

The red-tape idiocies are illustrated by the project to raise the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, which spans the Kill Van Kull connecting New York Harbor with the Port of Newark. The roadway is too low for the larger "post-Panamax ships" (designed for the newly-widened Panama Canal), and the Port Authority thought it needed to spend $4 billion to build a new bridge or tunnel.

Then a long-time Port Authority employee, Joann Papageorgis, figured out that the roadway could just be raised within the existing arch of the bridge. The solution was like a miracle: It not only reduced costs from $4 billion to $1 billion, but also had virtually no environmental impact since it used the same foundations and right of way as the existing bridge.

Raising the Bayonne Bridge roadway was pro-environmental in every meaningful way. It would permit cleaner, more efficient ships into Newark Harbor, and avoid the environmental havoc to surrounding neighborhoods of a new bridge or tunnel.

But no official had authority to approve it without hacking through a jungle of red tape.

Here's some of the red tape: a requirement to study historic buildings within a two-mile radius even though the project touched no buildings; notice to Native-American tribes around the country to participate even though the project would not be disturbing any new ground; and 47 permits from 19 different agencies.

It doesn’t get more complicated than this

The environmental review for this project — again, a project with virtually no environmental impact — was 20,000 pages, including appendices. Proceeding on an expedited timetable, permits were finally awarded after five years. Then some self-styled environmentalists sued claiming….you guessed it, "inadequate review." The Port Authority started construction anyway, and hopes to complete the project in 2019, 10 years after the application was filed.

Where is Congress?

Only Congress has the power to change old laws, to make sure they work in the public interest. Congress's responsibility also includes making sure laws work together. Viewed alone, a law may seem perfectly reasonable.

But if all the laws cumulatively harm the public, then Congress has the obligation to change them.

The problem is, in the vast majority of cases, Congress doesn't even have the idea of fixing old law. It treats old law like the Ten Commandments — except that now it's more like the Ten Million Commandments.

Like sediment in a harbor, the accretion of old law prevents America from getting where it needs to go. What's missing is not mainly money: President Obama had over $800 billion in the 2009 stimulus but, five years later, had been able to spend only 3.6 percent on transportation infrastructure. As he put it, "there's no such thing as shovel-ready projects."

What's missing is that no human has authority to use their common sense.

The harm to the public is intolerable. A study by Common Good, which I chair, found that the red-tape delays for infrastructure more than double the cost of large projects. The study also found that lengthy environmental review is dramatically harmful to the environment by prolonging polluting bottlenecks.

Environmental review is a good idea, but something is obviously amiss when the review of the environmental effects actually is environmentally harmful.

Greener countries like Germany are able to do environmental reviews and permitting on major projects in one to two years. The secret to their success is — hold on to your hats — to let officials take responsibility to make needed decisions.

All the red tape in America comes from a deliberate congressional philosophy to prevent humans from making decisions. Everything is preset in laws and rules. Thus, in American government, the concept of relevance is irrelevant.

That's why the Bayonne Bridge required a study of historic buildings even though no buildings were affected. That's why the new Tappan Zee Bridge project was required to do traffic studies even though the new bridge was not affecting traffic flow.

Restoring responsibility to officials to make decisions is the only way to end this red tape paralysis. It doesn't mean they can do whatever they want — they would still have to do an environmental review, accountable to the President and to courts in egregious cases.

But instead of overturning every pebble, officials could focus on what's important. "Oh, you're just raising the bridge roadway using the same foundations? Give 50 pages on construction impacts of the project" (not 20,000 pages).

Restoring clear lines of authority is actually simple. Common Good has proposed three pages of legislative fixes to make this vision a reality. The proposal empowers officials to determine the scope and adequacy of review, to intercede in inter-agency disputes and to expedite lawsuits to keep projects moving.

Trump recently signed an executive order designed to expedite approvals a little by giving coordinating authority to a designated official. That recommendation was based in part on Common Good's work. Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao declared recently: "Business as usual is just not an option anymore." Even Senate Democrats'' proposed infrastructure plan commits to "accelerated project delivery." But talking about fixing the problem isn't enough.

Trump ultimately doesn't have legal authority to ignore these statutory dictates. Congress created all this bureaucracy. Only Congress can fix it.

And how about funding the infrastructure initiative, whenever it materializes? Congress has its head in the sand here as well.

Trump has vowed to push for a decade-long, $1 trillion initiative. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, the infrastructure backlog is actually over $4 trillion, including: congestion on 40 percent of Interstate Highways; an antiquated power grid that wastes the equivalent of 200 coal-burning power plants; in New York State, 2,000 structurally deficient bridges and, in New York City leaky water mains that are almost a century old.

Delays on some of these projects could be disastrous. The two rail tunnels under the Hudson River, for example, are over 100 years old, and were damaged by superstorm Sandy. When they are forced to shut down for emergency repairs, the traffic jams could stretch for 25 miles.

Two new tunnels and other rail upgrades in and out of Penn Station are almost ready for construction. But this "Gateway Project" costs over $20 billion. Even with expedited reviews, and funding from state and local government, it will take a major financial contribution from Washington.

Yet Congress, or more accurately, the Republicans in Congress, refuse to advance any responsible plan to fund an infrastructure initiative. They don't dispute that infrastructure funding would be an excellent public investment — improving competitiveness, adding jobs and building a greener footprint. The sticking point is the Republican mantra — almost a theology — that they can never, never ever, raise any taxes.

Infrastructure does not, however, grow on trees. Trump in his campaign suggested that infrastructure could be funded with private investment.

Indeed, some infrastructure projects, such as transmission lines and toll roads, can be financed privately because they have revenue streams. But adding new lanes on congested highways, shoring up old dams and expanding sewage capacity will generally require public funding.

Where can infrastructure funding come from? One obvious source is the gasoline tax, which hasn't increased in 24 years. Raising the gasoline tax by 25 cents would raise over $40 billion per year, and fund most needed highway and transit projects. This could be supplemented by a "carbon tax" on other fossil fuels. Another funding source would be tax revenue from repatriated offshore corporate earnings.

New fees and taxes come out of our pockets, of course. But kicking the can down the road will cost us far more. An hour stuck in a traffic jam is multiple times more expensive than an extra 25 cents on each gallon of gasoline. Deferring maintenance is generally economically disastrous — increasing costs by a factor of 10, as occurred when the cables and girders of Williamsburg Bridge had to be replaced due to decades of neglect.

Doesn't Congress have a responsibility to do what's right here? Our parents and great-grandparents paid for the infrastructure that we now use. A great city, a great country, can't thrive with decrepit roads, rails and pipes.

Every time you're in a traffic jam — starting, say, this afternoon — think about Congress. It created a paralytic regulatory structure that prevents fixing infrastructure. Now it also refuses to help pay for it. Only Congress can cut these bureaucratic knots, raise funds, and get America moving again.

Philip K. Howard is chairman of Common Good, a legal- and regulatory-reform organization, a New York City-based civic leader, a lawyer, author of, most recently. The Rule of Nobody and a photographer.

Llewellyn King: Six flawed assumptions by Trump

Trainee pilots, during that phase of training known as pilotage, are taught to navigate by ground reference. The danger is the students will assume things: The river, the golf course or any other landmark they see may not be the one near the destination. Assumptions are dangerous. My flight instructor warned me years ago, “Assumptions will kill you.”

But assumptions control everything, from the expectation that your car will start in the morning to the belief this or that party will govern better.

In their turn, political leaders are governed by their own world of assumptions; assumptions which morph in to beliefs and which, in turn, become in their proprietors’ minds facts and, in turn, policies.

Here are six of the motivating assumptions that underlie the presidency of Donald Trump to this point. They are flawed in different ways.

First: There is a huge unemployment problem. There isn’t. There is a shortage of workers which is beginning to affect productivity in everything, from new home building to new infrastructure construction.

If Trump is able to find a lot of new money for new infrastructure building and refurbishment, this skilled labor shortage will get worse. If you are a carpenter, crane operator, dump truck driver, electrician, plumber or welder, there is work aplenty. Just ask the electric utility industry or those building pipelines. The “help wanted” signs are out.

One caveat: The absolutely unskilled are close to being absolutely unemployable.

Second: The infrastructure is in deplorable shape and needs immediate attention. Here, the president is right. The question is, how will he fix it? In short, who will pay?

While the relevant committees of Congress have worked on the problem for years, they have been stymied by the lack of discretionary money in the budget. Every year, the highway bill makes it through with less money than its sponsors know that it needs. Ditto state spending.

Public-private funding, part of the presidential mantra, is tricky and only applies in certain circumstances where, eventually, the private investor can get the money out and make a profit. There is no magic formula. Sorry.

Third: Illegal immigrants are prone to committing crime. The evidence is not there, and study after study shows the opposite. This belief erroneously feeds the widespread animus against immigrants, legal and illegal.

Fourth: The economy is a “disaster.” It isn’t and it wasn’t when the president was elected. There is growth, but it is modest.

Fifth: The United States can unilaterally banish radical Islam the from the face of the earth. Religions and their extremes are, at best, contained not vanquished. Time and fatigue will put the evil genie back in the bottle, not American might.

Religions love martyrs – and Islam more so than most. Martyrdom is the sustaining force of today’s Islamic terrorism. Minting more martyrs will be counterproductive.

Sixth: Regulation has the U.S. trussed up and bound: a great giant cannot get up and produce goods and services and well-being for the people. Trump says that regulations should be reduced by two-thirds. But our regulatory burden is not as heavy as, say, that in Europe, and regulations do protect the public health and safety, among other things. That is why they were enacted in the first place.

Corporations complain and some regulations may be onerous. I have personally experienced the good and the bad. Two examples: when I was publishing magazines and I wanted them displayed on the streets of New York City, I had to offer the same incentives to 95,000 other newsstands, where I had no readers. On the other hand, disposing of solvent used in a small printing plant was bothersome and slightly expensive but necessary. Without the EPA goad, the solvent would go into the sewers, with cumulative bad environmental and public-health effects.

Bad assumptions make bad policy. Bad assumptions mostly come from hearsay and it would seem that the president hears many things from his friends: the time-honored New York City practice of schmoozing. It is a great tradition, but can lead to dubious assumptions, ergo beliefs and policies.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail is llewellynking1@gmail.com. A veteran publisher, broadcaster, columnist and international business consultant, he's based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C. and a frequent contributor to New England Diary.

.

Llewellyn King: Transport infrastructure urgency brings some comity to Washington

By the current standards on Capitol Hill, there is astounding comity in the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. The committee, which held its first hearing of the new Congress recently, exhibits a kind of good humor, of give and take, which largely ceased with the Gingrich Revolution of 1994.

What makes this committee different is that Republicans and Democrats are staring into the jaws of hell together, so to speak. Disparate as they are, from super-liberal Democrat Eleanor Holmes Norton, of the District of Columbia, to the committee’s conservative chairman, Bill Shuster, R-Pennsylvania, the members know that the nation’s infrastructure is in deplorable condition.

They know, too, that in the current Congress, with its GOP aversion to new taxes, there is not enough money to fix the deteriorating infrastructure. They know all too well the old saw about immovable objects and irresistible forces.

A panel of heavy infrastructure users, headed by business celebrity Fred Smith, founder and CEO of FedEx, laid out the choke points for his industry: air traffic control and the interstate highway systems.

One of Smith’s ideas for improving the nation’s highways, bridges and public transit systems is to raise the gasoline and diesel tax, which has languished since 1994. But he warned this might not be the whole answer when new forms of propulsion, like electricity and compressed natural gas are changing or threatening to change the transportation mix.

No one on the panel objected to the idea of taxes for infrastructure. The overriding concern was from committee members who wondered whether the money would be spent where it was planned or diverted to general revenue needs.

It interested me that it was Smith who recommended greater taxation. His panel colleagues, including Ludwig Willisch, CEO of BMW of North America, and David MacLennan, CEO of Cargill, did not demure. More important, Republican members of the committee swallowed the tax poison without visible physical effect. No retching, trembling or detectable palpitations.

The elephant in the room, of course, was the Trump administration. Candidate Trump promised a massive infrastructure leap forward.

No one seemed confident that spending hawks in the Congress would support such athletics. It is hard to be hopeful that President Trump will get all or any of the new money out of a Congress that is looking at escalating deficits.

Talking to people involved in infrastructure, one gets this picture: user fees are not enough and toll roads, favored in principle by many, do not raise enough money to attract and keep private investors. Philip White of the global law firm Dentons, points out that many of these have failed in Texas — ground zero for private enterprise — and have had to be taken over by government entities. Similar fates have befallen toll roads elsewhere.

The big initial boost for the infrastructure under Trump will not come from new money, but rather from authorizing previously delayed projects and easing regulations. There is also the current highway fund spending, which has risen somewhat.

But nobody, especially on the House committee, believes it is enough to reverse the relentless crumbling of roads and bridges. The real infrastructure funding need has been estimated to be as high as $6 trillion.

Back to FedEx’s Smith and what he thinks will work: a mileage tax, congestion pricing and high-access lanes on highways; a revised tax code, which would eliminate some of the anomalies that hamper strategic planning; privatizing air traffic control; and upgrading runways.

He pointed to Memphis, FedEx’s “SuperHub,” where there has been a huge gain in productivity with air traffic improvements financed by his company.

Cargill, for its part, sang the song of barges, shipping containers, trucks and railcars. “It is the interconnected nature of waterways, railways and highways — the three-legged stool of domestic transportation — that is important to keeping the United States competitive. When one mode of transportation is troubled, it affects the entire system,” MacLennan said.

All is not lost for infrastructure spending. Trump, it appears, is keen to say he has honored his campaign promises. And he promised big.

Get ready for taxes, fees and congestion charges. The need is great, the means slim and taxes, by another name, will come.

The House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee will need all of its evident camaraderie as it takes its shovel to the legislative tarmac.

Llewellyn King (llewellynking1@gmail.com), host of White House Chronicle on PBS, is a veteran publisher, columnist and international business consultant. He is also a frequent contributor to New England Diary. This piece first ran on Inside Sources.

Robert Whitcomb: Blue State economics; overrated fracking; ugly Route 114

This is the latest "Digital Diary'' column from GoLocal24.

Two somewhat related stories: General Electric moving to Boston and the Red State-Blue State economic divide

For decades, we have heard about the glories of the Sunbelt, now often called the Red States. These generally Republican-run places are cited as exemplars of economic growth. Their leaders also like to assert that unlike the Democratic-leaning Blue States they’re centers of individualism, and not wallowing in tax-supported programs.

But in any event, the Red States continue, after all these years of air-conditioning, to have the nation’s highest levels of poverty, the worst health indicesand the worst sociological problems, such as violence, illegitimacy, drug addiction and so on. The Blue States are, generally, the rich states and with much better social indices.

That’s in large part because the rich folks who run the Red States do everything they can to keep their taxes low, and thus, for example, favor sales taxes, which are regressive, over income taxes, which are not. Thus public infrastructure – in education, health, transportation and environment -- suffer.

Meanwhile, the Blue States, for their part, tend to put money into physical infrastructure, education and mass transit (in their metro areas) that help the locals keep churning out innovation. (Actually, if they want to get richer, they’d increase investmentin these areas.)

The suckers in places like much of the South follow the fool’s errand of electing anti-tax fanatics to keep the local lobbyists happy, with such political tools as touting the glories of guns to help distract the citizenry.

Because of federal policies that favor moving tax money from rich places to poor ones, Blue States heavily subsidizethe Red States, for all their latter’s whining about the Blue States’ ‘’socialistic’’ tendencies. After all, the people in the richer states pay more in federal income taxes than the ones in the poorer (generally the Red States) because Blue States’ policies have tended to make their citizens better paid than those in the Sunbelt. The real welfare states are the Red States. (An exception in all this is Utah, with its Mormon rigor.)

I have written about thesocio-economicgap between the Red and Blue States for years. And that gap seems to be widening again. Look at a new statistical analysis in an essay “The Path to Prosperity Is Blue,’’ by Professors Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson in theJuly 31 New York Times using U.S. Census and other government data.

Which gets us to GE, whose management, led by CEO Jeff Immelt, is moving from one Blue State, Connecticut, to Boston. The main reason is the density of engineering and other talent in Greater Boston, which Massachusetts’s very good public education, healthcare and transportation infrastructure has helped to build up. (That many of GE’s up-and-coming stars don’t particularly like their current boring suburban office park also played a role in the decision to leave the Nutmeg State. They want to be in an exciting city.)

Of course, while Connecticut’s infrastructure has been slipping it still is superior to most of the Red States’. Just the fact that it has lots of passenger trains gives it an advantage.

Massachusetts, under GOP and Democratic governors, has long accepted the importance of investment in infrastructure. That has helped make it and keep it rich – rich enough to send some of its residents’ income to Red States.

As Professors Hacker and Pierson note at the end of their piece: ‘’{W}e should remember that the key drivers of growth (and incomes} are science, education and innovation, not low taxes, lax regulations or greater exploitation of natural resources.’’

“And we should be worried, whatever our partisan tilt, that leading conservatives promote aneconomic model so disconnected from the true sources of prosperity.’’

xxx

Speaking of “exploitation of natural resources,’’ some states, and parts of states, have had famous booms from fracking for natural gas. One of the selling points has been that because burning natural gas contributes less to global warming than burning oil or coal, that fracking is an environmentally better. But increasing evidence that fracking releases huge amounts of methane at and near the drilling sites suggests that it’s far from the wonderful transition fuel away from oil and coal that it has been made out to be. Redouble efforts to boost wind, solar, hydro and geothermal, please.

xxx

It’s clear that the cold killer Vladimir Putin’s Russia is engaged in a relentless cyberwar against the United States. Failure to find ways to push back to undermine the Putin regime will only embolden him further. Clouding everything is Donald Trump’s admiration for Putin and the developer’s business dealings in Russia.

xxx

The Trump phenomenon and the return of the Clintons has of course elicited much denunciation of them. But why not more attacks on the people who hired them – the voters? Mr. Trump and Mrs. Clinton have been public figures for a very long time, and most oftheir strengths and dirty laundry have long been visible. In spite of that, Republican and Democratic primary voters gave them the nod, even when other candidates with good records in public service were running in both parties.

Perhaps this year’s primary campaign might encourage party organizations, in the states and nationally, to reduce the roles of the primaries, now conducted in electronic media echo chambers, and increase the influence of party elders. The idea would be to save the parties from an increasingly ill-informedcitizenry who wants to hear again and again the mantras that reinforce their wishful thinking.

Bring back the “smoke-filled rooms’’ filled with smart political operators insulated to some extent from the short-termism and demagoguery that some of the electronic media, in particular, facilitate.

Okay, this will probably neverhappen because it would be called “undemocratic’’ even though the parties legally have the right to determine their own rules for nominee selection. Indeed, the body politic would be healthier if the parties wrestled back the power and influence that they have lost to special-interest groups and hysterical media. The general election, of course, is quite a different creature.

And, while we’re at it, let’s bring back some of that pork-barrel spending, aka “earmarks’’ (a very minor part of government budgets) that has been a lubricant in getting legislation crafted and passed in the days before Congress became gridlocked.

Reform reform.

xxx

Route 114 in Middletown, R.I., on the way to the way to partly gorgeous Newport, is one of America’s uglier and more depressing stretches of strip malls and other commercial crud. Now that the Internet and middle-class wage stagnation are ravagingbrick-and-mortar stores, we can expect many more stores on this depressing stretch to close.

Hopefully, the abandoned commerce will be replaced by trees and other plants and such possible routes to a better future as solar-energy arrays or wind turbines.

xxx

Providence needs more revenue but putting parking meters around the Thayer Street retail area has been a loser so far. The confusion and cost to drivers associated with the meters has scared away many customers, already inconvenienced by the many parking spaces handed over to Brown as part of a desperate payment-in-lieu-of-taxes deal a few years back.

The money that the city makes from the meters may end up more than offset by lower real-estate taxes because of commerce killed by themeters. The city needs an agonizing reappraisal of this policy for Rhode Island’s Harvard Square.

Wayland Square, a few blocks away, seems to have avoided the worst effects of the meter invasion. Nearby free street parking and some large parking lots are probably the main reasons. Indeed, the square bustles with stores (some new) and eateries and lots of walkers and buyers.

In both places, denser and more frequent mass transit would help address the parking problem, and in a fiscally fairer way: The added sales tax that would go to the state from prospering stores and restaurants would help finance RIPTA expansion, in a virtuous circle.

Robert Whitcomb is overseer of New England Diary.

Philip K. Howard: How to bring parties together to fix infrastructure mess

Fixing America’s decrepit infrastructure shouldn’t be controversial—it enhances competitiveness, creates jobs, and helps the environment. And of course, it protects the public. Repairing unsafe conditions is a critical priority: More than half of fatal vehicle accidents in the United States are due in part to poor road conditions.

After years of dithering, Washington is finally showing a little life for the task. Congress recently passed a $305 billion highway bill to fund basic maintenance for five years. But the highway bill is pretty anemic—it barely covers road-repair costs and does nothing to modernize other infrastructure. The total investment needed through the end of this decade is actually $1.7 trillion, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. Further, the highway bill does nothing to remove the bureaucratic jungle that makes these projects so slow and costly.

But these two failures—meager funding and endless process—may actually point the way to a potential grand bargain that could transform the U.S. economy: In exchange for Democrats getting rid of nearly endless red tape, Republicans would agree to raise taxes to modernize America’s infrastructure.

Stalled funding. The refusal to modernize infrastructure is motivated by politics, not rational economics. By improving transportation and power efficiencies, new infrastructure will lower costs and enhance U.S. competitiveness—returning $1.44 for every dollar invested, according to Moody’s. That’s one reason why business leaders, led by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers—normally on the same page as congressional Republicans—have been pleading for robust public funding. As an added benefit, 2 million new jobs would be created by an infrastructure-modernization initiative, jump-starting the economy. That’s why labor leaders and economists have joined with the business community to advocate for it.

But these benefits largely accrue to society at large—not to the public entities funding the infrastructure. Because tolls and other user charges, where applied, rarely cover all the capital costs, the federal government often must subsidize public works if the United States wants modern interstate transportation, water, and power systems. As a matter of party ideology, however, Republicans have steadfastly refused to raise the gas tax and other taxes needed to fund infrastructure. This line in the sand was drawn in the 1990s because of the Republican conviction, widely shared by the public, that government is wasteful.

So when the highway trust fund expired this year, Congress found itself in an ideological struggle over how to fix potholes. Unfortunately, Washington’s answer is an inadequate funding plan that is also basically dishonest, resorting to gimmicks like selling oil from the nation’s strategic petroleum reserve at more than $90 per barrel (when the market price is closer to $40).

Red-tape waste. The Republican frustration about government waste is illustrated by the inefficiencies of infrastructure procurement and process. The arduous procedures by which public infrastructure gets approved and built shows that total costs could be cut in half by dramatically simplifying the environmental review and permitting processes—which can often consume a decade or longer. The water-desalination plant in San Diego, for example, which is vital for water-parched California, began its permitting in 2003. It finally opened in December 2015, after 12 years and four legal challenges.

Even projects with little or no environmental impact can take years. The plan to raise the Bayonne Bridge roadway, which spans a strait that connects New Jersey to Staten Island—in order to allow a new generation of post-Panamax ships into Newark Harbor—had virtually no environmental impacts because it used the same foundations and right of way as the existing bridge. Yet the project still required five years and a 20,000-page environmental assessment. Among the requirements was a study of historic buildings within a two-mile radius of the Bayonne—even though the bridge touched no buildings. Once approved, the project was then challenged in the courts based on—you guessed it—inadequate environmental review.

All of this process is expensive. The nonpartisan group Common Good (which I chair) recently published a report on bureaucratic delays, Two Years, Not Ten Years, which found that decade-long review and permitting procedures more than double the effective cost of new infrastructure projects. Delay increases hard costs by at least 5 percent per year. Delay prolongs bottlenecks and inefficiencies, which totals 10 to 15 percent of project costs per year (depending on the infrastructure category). A six-year delay, typical in large projects, increases total costs by more than 100 percent.

Careful process, the theory goes, makes projects better. But the U.S. approval process mainly produces paralysis not prudence. America’s global competitors don’t weigh themselves down with these unnecessary costs. Take Germany: It is a far greener country than the United States, yet it does environmental review in a year not a decade. Germany is able to accomplish both review and permitting in less than two years by creating clear lines of authority: A designated official decides when there has been enough review and resolves disputes among different agencies and concerned groups. The statute of limitations on lawsuits is only one month, compared with two years in the United States—and that two years is only because it was shortened under the new highway bill. Following Germany’s lead, Canada recently changed its permitting process to complete allreviews and other infrastructure decisions within two years, with clear grants of authority to officials to meet deadlines.

Like most laws, America’s infrastructure process has its supporters. Any determined opponent of a project can “game” the procedures to kill or delay projects it doesn’t like. And, just as most Republicans are adamant about not raising taxes, many Democrats are adamant about not relinquishing the effective veto power environmentalists currently wield. After all, who knows when a new Robert Moses might appear to flatten urban neighborhoods?

Spending years arguing about if the project is worthwhile rarely improves the decision.

The tragic flaw in this position, however, is that lengthy environmental review is dramatically harmful to the environment. Prolonging traffic and rail bottlenecks, the Common Good report found, means that billions of tons of carbon are unnecessarily released as officials, environmentalists, and neighbors bicker over project details. America’s archaic power grid—not replaced in part because of permitting uncertainties—wastes electricity equivalent to the output of 200 coal-burning power plants. At this point, the decrepit state of America’s infrastructure means that almost any modernization, on balance, will be good for the environment. Water pipes from 100 years ago leak an estimated 2.1 trillion gallons of water per year. Faulty wastewater systems release 850 billion gallons of waste into surface waters every year. Overall, America’s infrastructure receives a D+ rating from the American Society of Civil Engineers. For every project that is environmentally controversial, such as the Keystone pipeline, there are scores of projects that would easily provide a net benefit to the environment.

In some vital projects, adhering to rigid legal processes could even lead to catastrophe. For example, the proposed new rail tunnel under the Hudson River must be completed before the adjoining tunnel is shut down to repair damage caused by Hurricane Sandy. Any delay in approvals would cut rail capacity to Manhattan from New Jersey in half, with unthinkably bad consequences on traffic, carbon emissions, and the economy.

Environmental review is important, but the tough choices required can usually be understood and aired in a matter of months not years. The trade-offs for the most part are well known: A desalination plant will produce one gallon of briny byproduct for every gallon of clean water; the new rail tunnel under the Hudson River will require dislocating homes and businesses at either end; a new power line will emit electromagnetic energy and mar scenic vistas. But California’s fresh water must come from somewhere, New York needs to eliminate rail bottlenecks, and new power lines will carry clean electricity to cities from distant wind farms. In each case, the relevant questions are whether the new project is worth the costs and, sometimes, whether there’s a practical way to mitigate the effects. Spending years arguing about if the project is worthwhile rarely improves the decision—it only makes projects more expensive while prolonging pollution.

A new bargain. There’s a way to break the logjam caused by a lack of needed funding and an overabundance of process. Conservatives concerned about wasteful government should agree to raise taxes to fund infrastructure if liberals agree to abandon the bureaucratic tangle that causes the waste. This deal will cut critical infrastructure costs in half, enhance America’s environmental footprint, and boost the economy.

Adequate funding will get America moving with safe and efficient infrastructure. And abandoning years of process need not undermine environmental goals or public transparency. The key, as in Germany and Canada, is to allocate authority to make needed decisions within a set time frame. Public input is vital, but it can be accomplished in months. Plus, input is more effective at the beginning of the process, as adjustments can be made before any plan is set in the legal concrete of multi-thousand-page environmental-review statements.

Politically, of course, getting Republicans and Democrats to strike a bargain—more funding for less bureaucracy—won’t be easy. Special interests on both sides have their claws deep into the status quo. It is notoriously difficult to raise taxes, and curbing review timelines can sound like cutting corners. But America can’t move forward on infrastructure built two generations ago. Eliminating traffic jams, electricity outages, airplane delays, and unnecessary tragic accidents will be more than worth the small increase in taxes and a shorter review period.