Bella DeVaan, Rebekah Entralgo: Skimping on schools while squandering money on the rich

Plaque on School Street, Boston, commemorating the site of the first Boston Latin School building. Boston Latin, the city’s most prestigious high school, was founded in 1635, before there were “high schools,’’ making it by far the oldest public school in America.

Via OtherWords.org

As students have been returning to the classroom, school districts across the country are facing a historic number of teacher vacancies — an estimated 300,000, according to the National Education Association (NEA), the largest U.S. teachers union.

Some states are particularly hard hit, with approximately 2,000 empty positions in Illinois and Arizona, 3,000 in Nevada, and 9,000 in Florida.

How are political leaders responding? A number of rural Texas districts have moved to a four-day school schedule, creating major hassles for working parents. A new Arizona law will no longer require a bachelor’s degree for full-time teachers. Florida is allowing military veterans to temporarily teach without prior certification. Florida’s Broward County recruited over 100 teachers from The Philippines.

These band-aid actions ignore the root causes of the teacher crisis: low pay and burnout.

A new Economic Policy Institute report finds that teachers made 23.5 percent less than comparable college graduates in 2021. That’s the widest gap ever — despite the extraordinary challenges teachers have faced during the pandemic. The gap is even wider in some of the states with the largest teacher shortages, reaching 32 percent in Arizona, for example.

Across the country, real wages for public school teachers have essentially flatlined since 1996.

When the NEA surveyed teachers earlier this year, 55 percent reported they plan to leave the profession sooner than planned. An overwhelming 91 percent pointed to burnout as their biggest concern, with 96 percent supporting raising salaries as a means to address burnout.

Some states are getting the message: In New Mexico, lawmakers have instituted minimum teacher salary tiers based on experience — beginning at $50,000 and maintaining a $64,000 median wage. They’re also aiming to codify annual 7 percent raises so that teachers don’t lose ground to inflation.

“These raises represent the difference of being on Medicaid with your family, the difference of having to have a second or third job or doing tutoring work on the side, the difference of driving the bus during the day and having to take extra routes just to make ends meet,” said New Mexico teacher John Dyrcz in a recent interview with More Perfect Union.

In other areas, teachers are harnessing their collective bargaining power to make their demands heard. Thousands of teachers in Ohio, Washington state, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C., went on strike during the first weeks of the academic year.

The educators’ union in Columbus, Ohio, demands a simple, public “commitment to modern schools”: not only pay raises but also smaller class sizes, decent air conditioning, adequate funding for the arts and physical education, and caps on numbers of periods taught in a row.

Read one picketer’s sign: “You think we give up easy? Ask how long we wait to PEE!”

Meeting such demands requires public investment. And unfortunately, too many lawmakers favor lining the coffers of the wealthy instead of funding our school systems.

In 2021, the Columbus Dispatch estimates schools in the city lost out on $51 million to local real estate developers. In New York, an over $200 million reduction in school budgets has provoked public outcry in a city where luxury builders have pocketed well over $1 billion in tax breaks each year.

The Columbus teachers union soon came to a “conceptual agreement” with the city’s schools, ending their strike. Let’s hope this is a sign of a turning tide. Through a relentless pandemic, vicious censorship of curricula, and surging inequality, we cannot continue to skimp on education while squandering our resources on the wealthy.

Rebekah Entralgo (@rebekahentralgo) is the managing editor for Inequality.org. Bella DeVaan (@bdevaan) is the research and editorial assistant for Inequality.org.

Chris Powell: Education disaster begins with parental neglect

Possible ways for such adverse childhood experiences as abuse and neglect to influence well-being through the lifespan, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

August's Titanic Deck Chairs Rearrangement Award seems likely to be won by the Education Committee of New Haven's Board of Alders (aka the city council), which, according to the New Haven Independent, in the face of catastrophic student performance data, spent much of its last meeting debating reading-instruction techniques even as 58 percent of the city's public school students are classified as chronically absent.

At least the meeting produced admissions from Supt. Ilene Tracy that for two years student mental health and "social-emotional learning" have displaced academic instruction and that student behavior is now "atrocious."

So it may not be surprising that the shortage of teachers, a national problem, is especially bad in New Haven's schools, which have about 300 unfilled positions amid a steady drain of teachers to school systems where salaries and students are better.

Of course while their political correctness doesn't help, New Haven's educators are mainly just playing the hand they have been dealt. They can't choose their students or the parents of their students.

But the disaster of education in New Haven and Connecticut's other cities has continued long enough that the Board of Alders, city legislators (including the influential New Haven Democrat Martin M. Looney, president pro tem of the state Senate), the state education bureaucracy, and Governor Lamont should have noticed by now that it is entirely a matter of demographics, the perpetual poverty arising from child neglect at home.

Instead these leaders keep clamoring for more programs to remediate the neglect rather than to address its cause and thereby prevent it -- and these programs keep failing spectacularly and expensively.

It is all an old of story of public education, documented in 1966 by the sociologist James S. Coleman, of Johns Hopkins University, who was assigned by the U.S. Office of Education to interpret the mass of school data collected at the direction of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Coleman's most important conclusion was recounted this month by the writer Ian V. Rowe in National Review magazine. Coleman wrote:

“One implication stands out above all: That schools bring little influence to bear on a child's achievement that is independent of his background and general social context; and that this very lack of an independent effect means that the inequalities imposed on children by their home, neighborhood, and peer environment are carried along to become the inequalities with which they confront adult life at the end of school.”

Coleman did not conclude that schools themselves don't matter at all. To the contrary, he found that disadvantaged children perform better in schools with better students, where standards are higher and peers set better examples. But that too was a matter of getting the children away from the bad influences of their home life.

In this respect the Coleman report echoed the findings of the report a year earlier by another sociologist, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who was then assistant U.S. labor secretary and who became a great U.S. senator. Moynihan blamed severe poverty and urban chaos on the breakdown of the family.

Indeed, the chronic absenteeism in New Haven's and other city school systems practically screams neglect of children by their parents, without even a whisper about teaching techniques.

If simply acknowledging the real problem in urban education in Connecticut is hard, it is harder still to imagine how politics would allow it to be addressed.

City officials and legislators cannot examine the causes of child neglect and educational failure without indicting their own constituents.

State officials can't examine the causes without indicting themselves for a welfare system that destroys the family while putting thousands of unionized and politically active "helpers" on the government payroll.

Educators, also numerous, unionized, and politically active, can't do it without calling more attention to their irrelevance and impugning their employment.

Academics like Coleman and Moynihan did it and some keep doing it, and journalism can call attention to their work. But if the trend toward illiteracy and ignorance keeps accelerating, there will be no one left to read it, much less act on it.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. He can be reached at CPowell@JournalInquirer.com.

Josh M. Beach: Why we can’t measure what matters in U.S. education

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

What do students learn in school? In the 21st Century, this question has become a political dilemma for countries around the globe. It is a deceptively simple question, but there has never been an easy answer.

The problem of measuring student learning appears to express an educational problem: What and how much do students learn? And yet, when you investigate the education-accountability movement, especially in the U.S. where it began, you realize that the preoccupation with student learning is not about education. Calls for accountability have always been more focused on politics and economics.

Accountability metrics were created to sort and rank students, teachers and schools in order to create a competition where some are winners and most are losers. This type of competitive environment creates fear, and it is not conducive to learning or high performance.

Most student learning, especially the most important types of social learning and formative interactions, happens outside school, especially in early childhood. These personal experiences later go on to affect students’ performance in schools. The most important variables that affect a student’s school achievement are environmental. They occur outside schools and affect children long before they ever set foot in a school. These three variables, which are deeply intertwined, are the social construction of: race, parental income and wealth, and parental education (especially the highest level of schooling that parents achieve).

All three of these variables are proxies for a wide range of social and economic resources that can help students learn and succeed in school, such as parenting skills and child development, especially the time parents spend talking to and reading with children, proper nutrition, access to tutors and extracurricular activities, access to top-quality schools with the best teachers, and also peer networks.

Most policymakers and school administrators talk as if schools and teachers have complete control over the student learning process, but most of the important variables that determine student success, especially in terms of learning and graduating, are beyond the control of teachers or schools.

As W. Edwards Deming pointed out, “Common sense tells us to rank children in school (grade them), rank people on the job, rank teams, divisions … Reward the best, punish the worst.” (This common-sense belief is wrong, especially, as Deming emphasized, when it comes to schooling, where the objectives are supposed to be student learning and personal development.)

Over the past half century, social scientists have found that there can be many unintended and adverse consequences when high-stake metrics get linked to individual or institutional evaluations tied to punishments and rewards.

This predicament is often called Campbell’s Law. The psychologist and social scientist Donald T. Campbell explained in 1976, “The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

A British economist put it more bluntly in what is now called Goodhart’s Law: “Any measure used for control is unreliable.”

According to Campbell, “When tests scores become the goal of the teaching process, they both lose their value as indicators of educational status and distort the educational process in undesirable ways.”

How have accountability measurements corrupted schools? Take high-stakes standardized testing as a perfect example. Many teachers now spend most of their classroom time teaching to the tests by giving students “tricks” to answer multiple-choice tests or “ways to game the rules used to score the tests,” according to Harvard Graduate School of Education Prof. Daniel Koretz. Students engage in little, if any, real or useful learning.

Grade inflation

Teachers have also been lowering their standards and inflating grades to make students look much more successful academically than they actually are. Some administrators have been manipulating the tested population of students to make sure the lowest-performing students don’t take high-stakes tests. Sometimes, this has taken the form of transferring low-achieving students to other schools or encouraging them to drop out of school. And most shamefully, some teachers and administrators have been engaging in plain old cheating by falsifying student achievement scores.

To make matters worse, because performance measures cannot be verified, judgments of quality are made on existing data, which can be manipulated, or can be partially or wholly fraudulent. This leads to the adverse selection of personnel, whereby deceitful agents who post the best performance markers get rewarded, even though their numbers may be questionable, if not fraudulent.

Often, as Koretz points out, “the wrong schools and programs” get “rewarded or punished, and the wrong practices may be touted as successful and emulated.” The opposite is also true. Honest, hard-working and effective teachers, with true but lackluster performance measures, are passed over for promotion, criticized, sanctioned or fired. Such moral hazards create a perverse Darwinian scenario: Survival of the corrupt.

When performance goals are mandated from above without employee input, subordinates are forced to follow meaningless targets without any intrinsic motivation. Thus, the only incentive for workers to succeed are extrinsic rewards, often money, which leads to shortcuts or fraud to get the monetary reward. Staff begin chasing performance markers for the monetary incentives without knowing about or caring about the fundamental purposes of the organization or the rationale behind accountability goals.

Thus, when it comes to schools, whenever lawmakers or administrators institute a single, predictable measure of academic performance linked to extrinsic rewards, whether it be for students, teachers, or the whole school, someone somewhere will be cheating to game the system.

A 2013 Government Accounting Office report concluded that “officials in 40 states reported allegations of cheating in the past two school years, and officials in 33 states confirmed at least one instance of cheating. Further, 32 states reported that they canceled, invalidated or nullified test scores as a result of cheating.” One scholarly study estimated that “serious cases of teacher or administrator cheating on standardized tests occur in a minimum of 4-5 percent of elementary school classrooms annually.” Temple University psychologist Laurence Steinberg sardonically quipped, “Fudging data on student performance” has been “the only education strategy that consistently gets results.”

Nationwide in the U.S., we are seeing the consequences of this cynical calculation. For decades, researchers have documented rampant social promotion and grade inflation in K-12 schools and in most institutions of higher education. Koretz has argued that grade inflation is not only “pervasive,” but also “severe,” so much so that he argued that this type of subtle cheating is “central to the failure of American education ‘reform.’”

In Houston, as an example, some high schools were officially reporting zero dropouts and 100% of their students planning to attend college, and yet one principal joked, most of her students “couldn’t spell college, let alone attend.” While Texas pioneered accountability reforms in K-12 education, which became national policy through George W. Bush’s landmark No Child Left Behind law, researchers have documented how those reforms led to the corruption of education in Texas. Policymakers and administrators lost sight of education in a push to fudge the numbers so they could secure public accolades, get more funding and build bigger football stadiums.

And what is the impact of grade inflation on students? While students no doubt like high grades that they have not academically earned, they are actually harmed a great deal by such educational fraud. First of all, students become complacent and are unmotivated to learn because they think they already know it all. When students are confronted with higher academic standards in the future, they are liable to wilt under the pressure and either blame themselves or the teacher for the difficulty of authentic learning.

Disadvantaged students hurt most

To make matters worse, grade inflation affects disadvantaged students the most. Poor students and ethnic minorities, who are often segregated in the lowest-performing schools in the poorest neighborhoods, often receive the most inflated grades. This is because their teachers often can’t teach effectively due to various social, economic and environmental conditions that obstruct the learning process.

And what happens when academically underachieving high-school students fail upwards and make it into college, mostly through the open-door community college? They are then confronted with the fact that they are unprepared for academic success.

Large percentages of freshmen in the U.S. have to start college with remedial classes because they were not adequately prepared in high school. Most of these remedial college students eventually drop out of college, for various reasons, never earning a degree, and often with substantial amounts of student debt. However, many are also just passed through the college system with inflated grades and little learning.

For decades, researchers have documented the lowering of academic standards and the inflation of grades at institutions of higher education all across the U.S., especially at community colleges.

Graduating with a degree

High grades also seem to be inversely correlated with the main measure of student success in college, which is graduating with a degree. Currently, over 80% of all college students in the U.S. are earning A or B grades, but less than half of students who enroll in higher education will actually graduate with a bachelor’s degree.

As college admissions rose, graduation rates declined from the 1970s to the 1990s because standards remained relatively high. But as admissions continued to rise, graduation rates began to increase starting in the 1990s. Students were no more academically prepared, in fact, they were less prepared, so the increase in completion rates was mostly likely due to political and administrative pressure. New accountability reforms most likely contributed to a lowering of standards, especially at non-selective public colleges and universities.

Education researchers Ernest T. Pascarella and Patrick T. Terenzini pointed out in 2005 that only about half of all college graduates “appear to be functioning at the most proficient levels of prose, document or quantitative literacy,” which means that all those inflated A and B grades aren’t translating into actual knowledge or skill, putting many college graduates at a disadvantage when they enter the labor market, and putting many firms at risk because they have hired ignorant and incompetent college graduates.

While it is certainly reasonable for teachers to use tests and grades to evaluate and measure student learning, these tools are not easy to implement in a valid way that promotes student learning and development. As Jack Schneider of the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, notes, “Measuring something as complicated as student learning” is very difficult, even under the best of circumstances, but almost impossible when it has to be done in a “uniform and cost-restricted way.” {Mr. Schneider is associate professor of leadership in education at UMass Lowell and director of research for the Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment.}

Josh M. Beach is the author of a number of interdisciplinary titles, including How Do You Know?: The Epistemological Foundations of 21st Century Literacy and Gateway to Opportunity? A History of the Community College in the United States. He is the founder and director of 21st Century Literacy, a nonprofit organization focused on literacy education and teacher training.

Georgian-style Longfellow Hall at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, in Cambridge, Mass. It’s named for the daughter of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the famous 19th Century poet and scholar.

Charles Chieppo: Teacher education in a bad way, but there's hope

BOSTON Both a national nonprofit organization and the U.S. Department of Education have recently turned their attention to education schools that long have failed to produce teachers equipped to improve student achievement. The same focus that highlights just how grim the current situation is will be needed on an ongoing basis if we are to solve the stubborn teacher-preparation problem.

A new report from the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) rates 1,668 elementary and secondary teacher-preparation programs at 836 colleges and universities using criteria including content preparation, practice teaching and student-admission requirements. Sadly, a majority of the programs fall into the lowest of four categories.

The report places only 26 elementary and 81 secondary programs in its top grouping. Programs that prepare elementary teachers are 1.7 times more likely to fall into the failing category than their secondary-education counterparts. One reason, according to NCTQ, is that so many of them continue to disregard scientifically based reading-instruction methods.

Teacher-prep programs have long fallen short in science, technology, engineering and math. Nearly half the programs NCTQ reviewed failed to ensure that their teacher candidates were capable of STEM instruction. Many of the programs require little or no elementary-school math coursework and don't mandate a single science class.

NCTQ said that just 5 percent of the programs it reviewed have all the components in place for a strong student-teaching experience.

The academic strength of incoming teacher candidates is another longstanding problem. NCTQ found that three-quarters of the programs it reviewed don't insist that applicants fall in the top half of the college-going population.

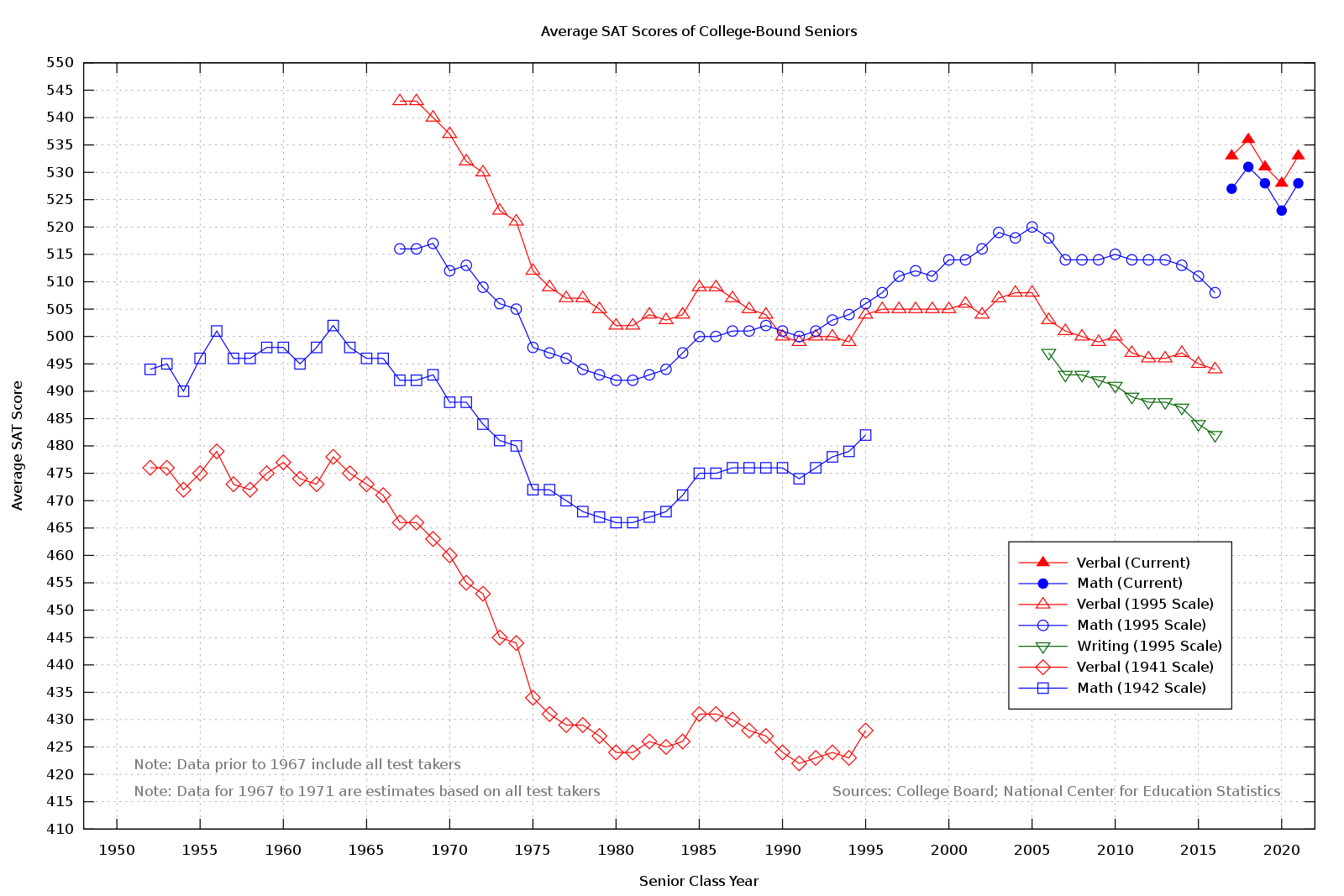

In 2010, the SAT scores of students intending to pursue undergraduate education degrees ranked 25th out of 29 majors generally associated with four-year degree programs. On average, the credentials of candidates for graduate education programs also were dismal, and among those candidates undergraduate education majors score the lowest.

Rules proposed last month by the Department of Education are a step in the right direction. They would require teacher-preparation programs to either show proof that their graduates have the skills to advance student learning or lose the ability to offer prospective teachers federal financial aid. "This is nothing short of a moral issue," Education Secretary Arne Duncan told Education Week.

The 1998 version of the Higher Education Act directed states to identify poor-performing teacher-prep programs, but 34 states have never identified a single one. The new proposed rules would require states to place each program in one of four categories ranging from "low performing" to "exceptional." Those rated below "effective" for two of the three previous years would be blocked from offering students federal Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education grants. The problem with the proposed rules is the timeline: There would be no withholding of grants until the 2020-21 academic year at the earliest.

For decades, public education in general and education schools in particular have been permeated by a Lake Wobegon culture in which everyone is assumed to be above average and mediocrity is the norm. But education consumes a huge part of state and local budgets, and many teacher-preparation programs are part of publicly funded colleges and universities. Fixing those programs is imperative if we are to improve the return on our education investment.

Charles Chieppo is a research fellow at the Ash Center of the Harvard Kennedy School. His email address is:

charlie_chieppo@hks. harvard.edu