Philip K. Howard: Our governing processes have become paralytic, and what to do about it.

The Bayonne Bridge, where an urgently needed improvement has been blocked by inane regulatory red tape.

Crook Point Bascule Bridge (1908), once connecting Providence and East Providence, R.I. It’s been stuck in upright position since 1976.

— Photo by Matthew Ward

Governing is not a process of perfection. Like other human activities, governing involves tradeoffs and trial and error. One of the most important tradeoffs involves timing. Delay in governing often means failure. Nowhere is this more true than with environmental reviews for infrastructure. Every year of delay for new power lines, modernized ports, congestion pricing for city traffic and road bottlenecks means more pollution and inefficiency.

New York Times columnist Ezra Klein has awakened liberal readers to the reality, hiding in plain sight, that governing processes are paralytic: “The problem isn’t government. It’s our government. … It has been made inefficient.”

The other week columnist George Will asked whether America “can do big things again.” Citing our work, and the absurd 20,000-page review for raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, which connects Bayonne, N.J., with New York City’s Staten Island, to permit new post-panamax ships into Newark Harbor, Will calls out “the progressive aspiration to reduce government to the mechanical implementation of an ever-thickening web of regulations that leaves no room...for judgment.” American Enterprise Institute scholar and Washington Examiner columnist Michael Barone, also citing our work, the other day called for a rebooting of government to “sweep out the ossified cobwebs.”

The recent $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure law contains tools to streamline permitting, including presumptive 200-page limits on environmental reviews and two-year processes that we championed. But actually giving permits requires officials to use their judgment about priorities and tradeoffs, not to overturn every pebble. That may be a problem in current bureaucratic culture. In a letter to the editor of The Washington Post, an environmental official objects to my suggestion that raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge using existing foundations “involved no serious environmental impact.” He asserts that “bringing larger, more polluting ships and increased cargo” to the port “would result in increased diesel pollution from both the ships and the trucks transporting the cargo.”

Actually, the new larger ships are much cleaner, pollution-wise and burn much less diesel fuel per container. That’s a reason they’re more efficient. Increasing the capacity of the Newark port will indeed result in more truck traffic, but those containers have to come in somewhere.

You start to see the problem. It’s impossible to talk about environmental impact in the abstract. What’s needed is a governing culture that can make judgments about practical tradeoffs.

In a piece for Fortune on efforts to protect kids online, Jonathan Haidt and Beeban Kidron cite my work on the benefits of a principles-based approach to writing laws.

Julia Steiny in the Providence Journal cites my work in describing how Providence public schools are being crushed by law: “The system suffers from what author Philip Howard calls The Rule of Nobody. He says that the law operates ‘not as a framework that enhances free choice but as an instruction manual that replaces free choice.’”

For the American Spectator, E. Donald Elliott provides a history of Common Good’s effort to bring about infrastructure permitting reform.

Philip. K. Howard is a New York-based lawyer, civic and cultural leader, author and photographer. He’s chairman of the legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org) and the author of, among other books, The Death of Common Sense and The Rule of Nobody.

Philip K. Howard: How to fight back against the forces that are tearing apart America: End the ‘vetocracy’

Trump supporters crowding the steps of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 as they prepare to force their way into it to try to overturn the election won by Joe Biden.

— Photo by TapTheForwardAssist

NEW YORK

What can we do about our country? That’s the question I hear most often. Washington is mired in a kind of trench warfare, with no prospects of forward movement. And Americans today can be divided into two camps: discouraged or angry.

Americans are retreating into warring identity groups as extremists demand absolutist solutions to defeat the other side. It’s nighttime in America.

Yet, Americans still share basic values of self-reliance, tolerance and practicality, surveys show. Put Americans in a crisis, and unfailingly they put themselves on the line to help their fellow citizens, as essential workers did during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Do we really hate each other? I don’t think so. We’re being forced apart by organized forces that profit from polarizing the country.

Extremists have the stage, and are relishing their new power to cow reasonable people into unreasonable positions — whether to deny the results of elections or benefits of vaccines, or to demand that most Americans wear hair shirts because of the sins of their ancestors.

Political insiders are manipulating extremism to their own goals. Political parties no longer compete by accomplishment but by stoking fears that the other side is worse.

The bottom line: Washington will not pull America back from the extremist precipice.

New leaders are obviously needed. But new leaders are not sufficient. Remember that Barack Obama promised “change we can believe in.” When that didn’t work out, frustrated voters (albeit with almost 3 million fewer votes than Hilary Clinton got) elected his polar opposite, Donald Trump, who promised to “drain the swamp.” Nothing much changed except more frustration, leading to greater extremism.

A new governing vision is needed – one that appeals to common interests while also responding to our frustrations. To talk polarized Americans off the precipice, we must understand how we got to the edge of this cliff.

The root cause of extremism, throughout history, is often a sense of powerlessness. Humans have an innate need for self-determination and opportunity. Can you do and say what you think makes sense? If not, sooner or later, you will want to break out. The Tea Party, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Stop the Steal: All these recent movements are ignited by a sense of powerlessness.

Government controls decision-making

What Obama and Trump failed to comprehend is this: The operating philosophy of modern government does not honor the role of human judgment in social activities. Instead of providing an open framework of goals and principles, activated by people taking responsibility, government strives to supplant human agency altogether.

At every level of society, Americans have been disempowered from making the choices needed to move forward. The operating structures of modern society are versions of central planning – dictating exactly how to do everything.

Why do Americans feel powerless? Because they can’t make a difference, and neither can their elected officials.

A new governing vision is needed to address this powerlessness. What I propose is to restore the human responsibility model that the Framers envisioned. As James Madison put it, giving responsibility to “citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country.”

Law should set goals and boundaries, but leave implementation to responsible people. Our protection from bad choices is accountability, not mindless compliance. "No man is a warmer advocate for proper restraints," George Washington wrote, but you cannot remove “the power of men to render essential services, because a possibility remains of their doing ill.”

Building an open governing framework activated by human responsibility is not difficult – it’s far easier to articulate goals than to dictate the details of implementation. Look at any organization or agency that works tolerably well, and you will find people focusing on the goals, not legalities.

But this new governing vision represents a radical departure from the status quo. No longer can bureaucrats avoid responsibility by being sticklers for rules. No longer can one lousy teacher or loud parent get what they want by demanding their rights. People in charge will actually be in charge, and will be empowered to act on their judgment. Other people will be empowered to make the judgments to hold them accountable.

America has become a 'vetocracy'

The federal government will never return willingly to a governing philosophy built on the foundation of human responsibility. All the detailed rules and red tape may prevent forward progress, but they empower insiders to block anything they don’t like. The power in Washington is the power of veto – a governing structure that political scientist Francis Fukuyama calls a “vetocracy.”

Change must come from the outside. The vision for change is to replace red tape with human responsibility. Let Americans use their judgment again. Instead of compliance, give people freedom to hold others accountable.

This is how a free society and democratic government is supposed to work. Instead of driving Americans into warring camps by trying to force one conception of the good, this vision can unite Americans by empowering them to shape their own conception of the good within broad legal boundaries.

Allow Americans to make things work again, and the darkness will soon turn into morning.

Philip K. Howard, a lawyer, author, New York civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder and chairman of Common Good, a legal- and regulatory-reform nonprofit organization. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left. Mr. Howard is a friend and former colleague of New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, who has worked on several Common Good projects in the past.

Philip K. Howard: Reframing Andrew Yang’s ideas for a new political party

Andrew Yang

Every so often, a citizen emerges to challenge the political establishment. Ross Perot’s 1992 presidential run drew on a public hunger for a new approach; he received 20 percent of the vote. In 2016 Donald Trump steamrolled traditional Republican candidates and changed the party’s face to his own. Andrew Yang is more a firecracker than a depth charge, but he has captured the public imagination with his refreshing candor and fearlessness.

Unlike Perot or Trump, Yang came from nowhere—no public reputation, no big money, no access to any part of the establishment. Yet, by force of his personality, Yang now has a pedestal in the political landscape. In his new book, Forward: Notes on the Future of Our Democracy, Yang plants the flag of a new political party. He argues that, though Americans are not as polarized as polls suggest, neither existing party will address the legitimate needs of the other side. He also says that the two parties are comfortable with their duopoly of failure—first you fail, then I fail—and therefore will not support disruptive electoral reforms such as ranked-choice voting.

Yang is not the first to suggest that our two political parties no longer represent most Americans. Frank DiStefano, in his recent essay in these pages, argued that the parties are on “a locked-in path to destruction and decline.” In my 2019 book, Try Common Sense, which Yang cites, I said that each party’s outmoded ideology precludes the overhauls needed to respond to public frustration.

It is no surprise that a plurality of voters now identifies as “independent” or as a member of a third party. But the electoral machinery makes it difficult for a would-be candidate to operate outside the two parties; and the primary system promotes extremists, not problem solvers.

Yang’s idea of a party is, initially, not one with its own candidates but a centrist movement that exercises influence on candidates from both parties. As DiStefano elaborates it, a movement that captures public imagination can eventually take over or supplant one of the parties. The challenge is to galvanize public support for this type of new overhaul movement in a political environment like today’s, which breeds deadlock, not solutions. While many Americans might be receptive to a new party, the current political shouting match has left them exhausted and cynical. There is a huge gulf today between wanting change and rolling up your sleeves to force change.

So, what does it take to engender the excitement needed for a new movement? Yang proposes a six-point platform for his Forward Party:

1. Ranked-choice voting, with open primaries: These arrangements would reduce the stranglehold of the two parties and defang the extremists.

2. Fact-based governing: The idea here is to evaluate programs objectively.

3. Human-centered capitalism: Yang wants to re-center business around employees and communities, not just owners.

4. Effective and modern government: Here Yang embraces the need to “fix the plumbing” of paralyzed government.

5. Universal Basic Income: Giving Americans $1,000 per month was Yang’s signature proposal in his presidential campaign—a proposal that was validated, he argues, by the Covid relief payments.

6. Grace and tolerance: Yang urges Americans to be more accepting of each other, not stay locked in a battle of identity politics.

By opening the door to a new party, Yang once again reveals solid leadership instincts. But a new movement requires a tougher, more focused platform. A list of centrist do-good reforms is unlikely to elicit the public passion needed to dislodge the current parties. Yang himself is a bold and disarming figure; his party must be as well. A new party needs a clarion call that can galvanize popular support—as the Progressive Movement did, for example, with its vision of public oversight of food and fair practices, or the New Deal with its idea of social safety nets. Successful movements also energize public passion by fingering villains, as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street did.

To get Americans out of their easy chairs, the new party must light a bonfire. Yet Yang’s platform is soporific, with no inspirational theme or evil targets. What’s the vision? Who are the enemies? Here is the way I would reframe Yang’s proposed Forward Party.

First, the clarion call for a new way of governing: Responsibility for America. Americans have lost their sense of self-determination. We should be re-empowered to make a difference. Revive individual responsibility at all levels of society. Replace mindless bureaucracy with accountability for results. Teachers should be free to do their best, with authority to maintain classroom discipline. Principals should be free to hold teachers accountable, and the same should hold true all the way up the chain of responsibility. Officials must be free to authorize action within a reasonable timeframe; and they, too, must be accountable up the chain of responsibility. Mayors and police chiefs should have authority to manage the police force and other departments, including authority to promote public employees who do their jobs and fire those who don’t.

Reviving human responsibility requires overhauling government’s operating systems, replacing thick rule books with simpler goals and principles managed by people who take responsibility for themselves and are accountable to others. This is not so hard: It is far easier to agree on goals than to bicker over endless details of implementation. Modern American government has become basically a bad form of central planning, tying Americans into knots of red tape. Ask any teacher or doctor. Restoring responsibility would empower officials and citizens to govern better and adapt to local needs.

Second, identify enemies and attack them. Powerful forces will resist a movement to revive responsibility. I see two main villains: public unions, which exist to block all accountability, and the political parties themselves, which have become organs of identity politics and special interests. It is impossible to fix broken government or revive a shared sense of national purpose without defeating these villains.

Public unions have made government unmanageable and must be outlawed. Public unions have preempted democratic governance. Citizens elect leaders to run the police force and schools, but these leaders have no authority to fulfill this responsibility. The Minneapolis mayor appointed the police chief; but under the police union’s collective-bargaining agreement, the mayor lacked authority to fire the rogue cop who killed George Floyd—or even to reassign the officer. Unlike private unions, which are dependent on the success of a private enterprise, public unions retain power even where they cause government to fail miserably.

Democracy is supposed to be a process of giving officials responsibility and holding them accountable. But public unions have broken the links: Today, there is zero accountability in the daily operations of American government. Without accountability, rote compliance with the thick rule books replaces individual responsibility for results. The bottom line today is a government bogged down in a bureaucratic jungle of dictates and entitlements. Nothing much works sensibly or fairly because no one is empowered to make things work.

As for political parties, they compete through failure, not achievement. Party leaders have basically given up on reforming government. Instead, they take turns in power pointing to the failures of the incumbent. In 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump tapped into broad public frustrations with Washington. Trump’s erratic leadership opened a door through which Joe Biden entered, offering sanity. But Biden’s failures of execution in Afghanistan and on the Mexican border now empower Republicans to go on the attack and prepare for their own return.

This spiral of negative democratic competition is accelerated by the rise of extremism: Each side stokes fear of the extremists on the other (“Defund the police!” “Stop the steal!”). Actually fixing government is no longer the way the parties compete.

Each party will aggressively resist reforms that would revive responsibility. Public unions have a stranglehold on the Democratic Party. Identity groups on the left will resist any accommodation of other points of view, or what Andrew Yang calls “grace and tolerance.” Republicans have become a party of nihilism and offer no discernible governing vision. They will rail against any reform that empowers public officials, opens elections to moderate candidates, or imposes taxes for public projects.

The existing political parties are the problem, not the path to a solution. The new party envisioned by Yang must ultimately supplant one of them. The new party must ask its supporters to defeat the defenders of the status quo: They are not the agents but the enemies of a successful future. Generating public enthusiasm will require not a laundry basket of reforms but a spear with a sharp point. No matter which party is in charge, focus on its virtually unblemished recent record of failure.

America needs a new party. Its vision must be condensed into a new governing principle that resonates with American values and represents a clean break from bureaucratic paralysis—a principle like human responsibility, which can guide an overhaul of all levels of government.

The current state of American politics has squeezed all energy and hope out of our democracy. There’s no oxygen to serve as fuel for anyone who wants to do what is needed. Yang has cracked open a door, but we need a new vision to open it wide and attract a public enervated by decades of failure.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, author, civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder of the government- and legal-reform nonprofit organization Common Good (commongood.org) and author, most recently, of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left (2019). This essay first appeared in American Purpose.

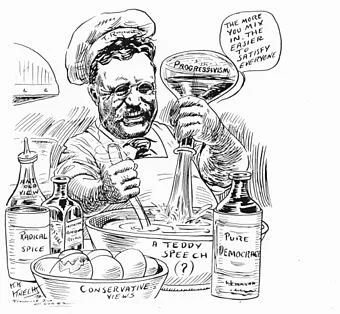

Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party’s (aka “Bull Moose Party’’) presidential candidate in 1912, mixing ideologies in his speeches in this 1912 editorial cartoon by Karl K. Knecht (1883–1972) in the Evansville (Ind.) Courier. The former president’s running mate was California Gov. Hiram Johnson.

Philip K. Howard: The administrative state is paralyzing American society

VERNON, Conn.

Philip K. Howard’s powers of concision are remarkable. In a very readable Yale Law Journal piece, “From Progressivism to Paralysis,” Howard, founder of the nonprofit and nonpartisan reform group Common Good (commongood.org), writes:

"The Progressive Movement succeeded in replacing laissez-faire with public oversight of safety and markets. But its vision of neutral administration, in which officials in lab coats mechanically applied law, never reflected the realities and political tradeoffs in most public choices. The crisis of public trust in the 1960s spawned a radical transformation of government operating systems to finally achieve a neutral public administration, without official bias or error. Laws and regulations would not only set public goals but also dictate precisely how to implement them. The constitutional protections of due process were expanded to allow disappointed citizens, employees, and students to challenge official decisions, even managerial choices, and put officials to the proof. The result, after fifty years, is public paralysis. In an effort to avoid bad public choices, the operating system precludes good public choices. It must be rebuilt to honor human agency and reinvigorate democratic choices.”

The gravamen of the article is that progressive precisionism causes paralysis because laws and regulations must be general and non-specific enough to allow administrative creativity. And, a correlative point, administrators should not be permitted to arrogate to themselves legislative or judicial functions that belong constitutionally to elected representatives.

Why not? Because in doing so the underlying sub-structure of democratic governance is subtly, and sometimes not so subtly, fatally undermined. The authority of governors rests uneasily upon the ability of the governed to vote administrators and representatives in and out of office, a necessary democratic safeguard that is subverted by a permanent, unelected administrative state that, like a meandering stream, has wandered unimpeded over its definitional banks.

Detecting a beneficial change in the fetid political air, Howard warns, “Change is in the air. Americans are starting to take to the streets. But the unquestioned assumption of protesters is that someone is actually in charge and refusing to pull the right levers. While there are certainly forces opposing change, it is more accurate to say that our system of government is organized to prevent fixing anything. At every level of responsibility, from the schoolhouse to the White House, public officials are disempowered from making sensible choices by a bureaucratic and legal apparatus that is beyond their control.”

And then he unleashes this thunderbolt:

“The modern bureaucratic state, too, aims to be protective. But it does this by reaching into the field of freedom and dictating how to do things correctly. Instead of protecting an open field of freedom, modern law replaces freedom.

“The logic is to protect against human fallibility. But the effect, as discussed, is a version of central planning. People no longer have the ability to draw on ‘the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place,’ which Nobel economics laureate Friedrich Hayek thought was essential for most human accomplishment. Instead of getting the job done, people focus on compliance with the rules.

“At this point, the complexity of the bureaucratic state far exceeds the human capacity to deal with it. Cognitive scientists have found that an effect of extensive bureaucracy is to overload the conscious brain so that people can no longer draw on their instincts and experience. The modern bureaucratic state not only fails to meet its goals sensibly, but also makes people fail in their own endeavors. That is why it engenders alienation and anger, by removing an individual’s sense of control of daily choices.”

Indeed, as a lawyer (sorry to bring the matter up), Howard probably knows at first hand that complexity, which provides jobs aplenty for lawyers and accountants, is the enemy of creative governance. The way to a just ordered liberty is not by mindlessly following ever more confusing and complex rules – written mostly by those who intend to preserve an iron-fisted status quo – but by leaving open a wide door of liberty in society for those who are best able to provide workable solutions to social and political problems.

Howard, I am told by those who know him well, is not a “conservative’’ in terms of the current American political parlance. For that matter, besieged conservative faculty at highbrow institutions such as Yale are simply exceptions that prove the progressive rule; such has been the case before and since the publication of Yalie William F. Buckley Jr.’s book, God and Man at Yale.

But I am also assured that Howard is an honest and brave man.

In an era in which democracy is being throttled by a weedy and complex series of paralytic regulations produced by the administrative state, any man or woman who can write this – “It is better to take the risk of occasional injustice from passion and prejudice, which no law or regulation can control, than to seal up incompetency, negligence, insubordination, insolence, and every other mischief in the service, by requiring a virtual trial at law before an unfit or incapable clerk can be removed” -- is worth his or her weight in diamonds.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Philip K. Howard: Principles to unify America

The Great Seal of the United States. The Latin means “Out of Many, One’’

“America is deeply divided”: That’s the post-mortem wisdom from this year’s election.

Surveys repeatedly show, however, that most Americans share the same core values and goals, such as responsibility, accountability and fairness. One issue that enjoys overwhelming popular support is the need to fix broken government. Two-thirds of Americans in a 2019 University of Chicago/AP poll agreed that government requires “major structural changes.”

President-elect Biden has a unique opportunity to bring Americans together by focusing on making government work better. Extremism is an understandable response to the almost perfect record of public failures in recent years. The botched response to COVID-19, and continued confusion over imposing a mask mandate, are just the latest symptoms of a bureaucratic megalith that can’t get out of its own way. Almost a third of the health-care dollar goes to red tape. The United States is 55th in World Bank rankings for ease of starting a business. The human toll of all this red tape is reflected in the epidemic of burnout in hospitals, schools, and government itself.

More than anything, Washington needs a spring cleaning. Officials and citizens must have room to ask: “What’s the right thing to do here?” If we want schools and hospitals to work, and for permits to be given in months instead of years, Americans at every level of responsibility must be liberated to use their common sense. Accountability, not suffocating legal dictates, should be our protection against bad choices.

But there’s a reason why neither party presented a reform vision: It can’t be done without cleaning out codes that are clogged with interest-group favors. Changing how government works is literally inconceivable to most political insiders. I remember the knowing smile of then-House Speaker John Boehner’s (R.-Ohio) when I suggested a special commission to clean out obsolete laws, such as the 1920 Jones Act, which, by forbidding foreign-flag ships from transporting goods between domestic ports, can double the cost of shipping. I also remember the matter-of-fact rejection by then-Rep. Rahm Emanuel (D.-Ill.) of pilot projects for expert health courts — supported by every legitimate health-care constituency, including AARP and patient groups — when he heard that the National Trial Lawyers opposed it: “But that’s where we get our funding.”

Cleaning the stables would help everyone, but the politics of incremental reform are insurmountable. That’s why, as with closing unnecessary defense bases, the only path to success is to appoint independent commissions to propose simplified structures. Then interest groups and the public at large can evaluate the overall benefits of the new frameworks.

Over the summer, 100 leading experts and citizens, including former governors and senators from both parties, launched a Campaign for Common Good calling for spring cleaning commissions. Instead of thousand-page rulebooks, the Campaign proposed that new codes abide by core governing principles, more like the Constitution, that honor the freedom of citizens and officials alike to use their common sense:

Six Principles to Make Government Work Again

Govern for Goals. Government must focus on results, not red tape. Simplify most law into legal principles that give officials and citizens the duty of meeting goals, and the flexibility to allow them to use their common sense.

Honor Human Responsibility. Nothing works unless a person makes it work. Bureaucracy fails because it suffocates human initiative with central dictates. Give us back the freedom to make a difference.

Everyone is Accountable. Accountability is the currency of a free society. Officials must be accountable for results. Unless there’s accountability all around, everyone will soon find themselves tangled in red tape.

Reboot Regulation. Too few government programs work as intended. Many are obsolete. Most squander public and private resources with bureaucratic micromanagement. Rebooting old programs will release vast resources for current needs such as the pandemic, infrastructure, climate change, and income stagnation.

Return Government to the People. Responsibility works for communities as well as individuals. Give localities and local organizations more ownership and control of social services, including, especially, for schools and issues such as homelessness.

Restore the Moral Basis of Public Choices. Public trust is essential to a healthy culture. This requires officials to adhere to basic moral values — especially truthfulness, the golden rule, and stewardship for the future. All laws, programs and rights mist be justified for the common good. No one should have rights superior to anyone else.

Is America divided? Many of the problems that caused people to take to the streets this year reflect the inability of officials to act on these principles. The cop involved in the killing of George Floyd should have been taken off the streets years ago — but union rules made accountability impossible. The delay in responding to COVID was caused in part by ridiculous red tape. The inability to build fire breaks on the west coast was caused by procedures that disempowered forestry officials.

The enemy is not each other, as President-elect Biden has repeatedly said. The enemy is the Washington status quo — a ruinously expensive and paralytic bureaucratic quicksand. Change is in the air. But the politics are impossible. That’s why one of first acts of President Biden should be to appoint spring cleaning commissions to propose new frameworks that will liberate Americans at all levels of responsibility to roll up their sleeves and make America work again.

American government needs big change, but the changes could hardly be less revolutionary. Instead of attacking each other, Americans need to unite around core values of responsibility and good sense.

Philip K. Howard is founder of Campaign for Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward.

Mr. Howard, a lawyer, is the founder and chairman of the nonprofit legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org), a New York City-based civic and cultural leader and a photographer. This piece first ran in The Hill.

Philip K. Howard: Let COVID crisis cut the bureaucracy that strangles education

How to bring them back?

The COVID-19 crisis could be the impetus that finally pushes the broken machinery of America’s schools over the cliff. Everyone is scrambling to figure out how to educate in a pandemic, and the answers will differ depending on the infection rates in particular communities and many other variables. Work rules, legal entitlements and one-size-fits-all bureaucracy are impossible to comply with.

Who decides? This is where the centralized education apparatus collapses of its own weight. Teachers unions want to control when and on what terms teachers return to work. Education regulators in Washington, D.C., and state capitals want to dictate answers with a new set of rules. They expect the COVID-19 education framework to come out of negotiations with unions, who have already threatened to strike if teachers must go back to the classroom.

The stranglehold by central bureaucrats and union officials over how schools work is why they fail so badly. Public schools are a giant assembly line of rigid work rules, legal entitlements, course plans, metrics, granular documentation, and legal proceedings for almost any disagreement, including classroom discipline and comments in a personnel file. Day after day, teachers and principals grind through the dictates of this legal assembly line. There’s little room for innovation or creativity, and not even the authority to maintain order. The only certainty is no accountability. No matter how much or how little someone tries, no matter how badly a school performs, there will be no effective accountability.

While teacher pay has stagnated over the past two decades, the percentage of school budgets going to administrators has skyrocketed. Half the states now have more noninstructional personnel than teachers. The Charleston County, S.C., school system had 30 administrators each earning over $100,000 in 2013. Last year it had 133 administrators earning more than $100,000. Union officials and central bureaucrats owe their careers to the bureaucratic labyrinth they create and oversee.

Now the unions want to devise a pandemic school assembly line. In addition to not returning to the classroom, ideas floated so far include a limit of three hours of online instruction, a preference for older teachers to teach online courses instead of teachers with demonstrated skills, and a refusal to allow classes to be recorded and accessed anytime because of privacy concerns.

Top-down dictates don’t work well in any setting, and particularly not in the pandemic. Some teachers want schools to reopen in their communities, but others will not want to take the risks of infection. Distance learning is an experiment just beginning; some teachers will be effective at distance learning, and others not. It may be better to record remote lessons by superstar teachers, and to supplement this with online tutoring. A hybrid model of distance learning with staggered attendance is also a possibility. Tailoring these techniques to particular populations and students holds the promise of effective education. But these experiments will surely fail if rigidly constrained by rules in advance.

A further complication is that parents need to get back to work. But they will also have different tolerances for exposure to risk. They will need not one mandated solution, but different alternatives. How about small learning pods, organized by neighborhoods, and overseen by teachers? This will require teachers to supervise and teach students of different ages. Different communities will require different approaches, taking into account the needs of the students and parents, the local infection rates, and other factors.

The urgency here could lead to innovations that are unimaginable to stakeholders stuck in current bureaucratic machinery. This disruption is also an opportunity to finally abandon the system and replace it with a set of core principles that restore ownership to educators and parents on the ground. These seem to me the core principles:

· Replace bureaucracy with periodic evaluations. Replace most mandates and reports with general goals and principles. Replace red tape with periodic evaluations by independent observers who judge a school by a number of criteria, including academic achievement and school culture.

· A new deal for teachers. Give teachers much more autonomy to run classrooms in their own ways. Remove most paperwork burdens, especially in special education. Use the funds now spent on excess administrators to pay teachers more, and to provide alternative education settings for disruptive students.

· Restore management authority. Restore the authority of principals (or other designated school leaders) to run a school, including allocating budgets. Because accountability is vital to an energetic school culture, principals or governing committees must be able to terminate teachers who are less effective. Instead of legal proceedings, safeguard against unfair personnel decisions by giving veto power to a site-based parent-teacher committee.

· Revive local autonomy. All stakeholders must have a sense of ownership of their schools. Within broad boundaries, communities should be free to set priorities and manage schools as they believe effective.

For several decades, public-school reforms have focused on measuring and rewarding specific output measures, notably test scores, or improving inputs, such as training programs and new technology. But the best measure of a school is its culture—with shared values, goals, energy and mutual commitment. That’s what good schools all share. It is impossible to have a good culture unless the teachers, administrators and many parents all feel a sense of ownership. That’s why top-down reform ideas have little impact, and why the accumulated red tape is counterproductive. Educators need to focus on their mission, not filling out bureaucratic boxes.

America ranks poorly in international student-achievement results despite spending more per-capita than all but a handful of countries. Teacher attrition is at 8 percent a year, with the best teachers burning out or quitting because of frustration with suffocating bureaucracy. Principals too are leaving, with one out of three saying that they plan to pursue different careers within five years.

No one likes the system. Over the years, I have worked with leaders of school systems across America, such as in New York City and Denver, with teachers unions, and with research firms such as Public Agenda. Everyone feels disempowered from doing what they think makes sense. But the key stakeholders are stuck in a kind of trench warfare, firing bureaucratic rules at each other. Union operatives and public administrators control compliance with, literally, thousands of pages of detailed requirements. Schools are stuck in the muddy no-man’s-land of legal mandates and people demanding their legal entitlements.

The only cure to what ails America’s schools is to abandon the massive bureaucratic machinery aimed at forcing everyone to make it work. The accumulated education bureaucracy crushes the human spirit and any chance of fostering energetic school cultures. The COVID crisis could be the impetus for a mutual disarmament. School bureaucracy should not be reformed but abandoned. It fails every constituency that matters—students, teachers, principals, parents, and the broader society—and it prevents the adaptability needed to cope with COVID-19.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, legal-system and regulatory reformer, New York City civic and cultural leader, author and photographer. He’s chairman and founder of Common Good (commongood.org). His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward. This piece was first published by Education Next.

Philip K. Howard: America needs a social contract to address COVID-19

The original cover of Thomas Hobbes's work Leviathan (1651), in which he discusses the concept of the social contract theory

America can’t stay closed indefinitely. But reopening America’s shops, schools and other public places is fraught with uncertainties and risks. In some jobs and settings the precautions may not be possible.

These risks and social controls conflict sharply with an American legal system that is built upon principles of uniform treatment, avoidance of risk, privacy, and, especially, free choice. Who makes these decisions? Is anyone liable when, inevitably, some people get infected?

Reopening society requires a new pandemic social contract, with new benefits and liability framework. Instead of avoiding risk, the guiding principle, as in wartime, should be to confront the risks of this common enemy and not to surrender our vibrant society in the vane hope that the virus will go away

Many institutions, retail establishments and employers will be reluctant to reopen because of fear of legal exposure. For some, the contingent liability risk may tip the balance against reopening. While it is impossible to know for certain where someone contracted the virus, it is quite easy to identify “hot spots” such as bars or meat-packing plants. Whether those businesses should reopen, and with what precautions, are decisions to be made by government, not by individual plaintiffs or their lawyers.

Trust in the new rules is essential for Americans to brave the risks and to adhere to the guidelines. A new pandemic social contract is needed that reassures Americans that they will not be left to fend for themselves if they get sick. Because the overhang of potential risk to individuals and liability to employers could significantly impact the national economy, this new social contract should be made as matter of federal law.

The best model for a reliable pandemic social contract is the workers’ compensation system, a no-fault program in which injured workers relinquish any right to sue in exchange for the employer’s agreement to fund health-care costs and wages. Because COVID-19 does not originate in unsafe workplace conditions, however, the new program should be funded predominantly by the federal government.

The new pandemic social contract could look like this:

America’s health-care patchwork is not well-suited to a pandemic. To avoid the inequities and inefficiencies of reimbursing health-care providers through thousands of different plans, the federal government should pay providers directly for all COVID treatments. The complexities of Medicare and Medicaid enrollment make them unsuitable as a conduit. A separate branch of theCenters for Medicare and Medicaid Services could be established to fund and audit COVID health-care costs, based on one guiding mandate.

Going forward, the federal government should fund COVID treatments.

Going back to work involves risks for each worker. Some will decide that it’s not worth the risk of exposure, and try to find jobs that allow them to work remotely. That will their choice. But Americans who choose to return to work should not bear the economic costs when they get ill.

Infected Americans with few symptoms should also be encouraged to quarantine so that they don’t infect co-workers. Sick employees should receive salaries as provided in state workers’ compensation schemes, except that, because the disease was not a workplace accident, the federal government should fund the vast majority of this, perhaps 90 percent. Leaving the employers with a small portion of the exposure will provide incentives to maintain safe workplace protocols, and also to oversee the validity of claims.

As part of the pandemic social contract, Congress should preempt liability except for cases of intentional misconduct—such as flouting safety guidelines. No one in America created COVID-19, and no one should be liable unless they deliberately misbehave.

Clarity in these lawsuit limitations is vital to give employers confidence that if they do not act irresponsibly, they will not be liable. No matter what the standard of liability, however, lawyers can be expected to push the envelope.

Intentional misconduct requires hard proof, but setting soft standards such as “gross negligence,” as some have proposed, can be easily circumvented by legal rhetoric. Perfect adherence to protocols is also unrealistic; sometimes the tables will end up 5 ½ feet apart instead of 6 feet. To reliably apply the liability limitations, Congress should create a special pandemic court to handle all pandemic injury claims, along the lines of the special vaccine court it created when concerns about liability basically shut down vaccine production.

Just as the federal government organizes and funds national defense, so too should it organize a comprehensive social contract for pandemics. Americans need a simple, fair framework they can rely upon to give them the confidence to go back to work

Philip K. Howard is a New York-based lawyer, author and chairman of the nonpartisan legal- and government-reform organization Common Good (and an old friend of the editor of New England Diary, Robert Whitcomb). He’s founder of the Campaign for Common Good. This essay first ran in The Hill.

Philip K. Howard: Misdiagnosing why America is a failed state

— Photo by Jblackst

NEW YORK

People want answers for what has gone wrong with America’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic—from lack of preparedness, to delays in containing the virus, to failing to ramp up testing capacity and the production of protective gear. But almost nowhere in the current discussion can one find a coherent vision for how to avoid the same problems next time or help restore a healthy democracy.

Bad leadership has been identified as a primary culprit. The “fish rots from the head,” as conservative columnist Matthew Purple puts it. There’s plenty to blame President Trump for, but stopping there, as, say, former New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani does, ignores many bureaucratic failures. Cass Sunstein gets closer to the mark by focusing on how red tape impedes timely choices, but even he sees the bureaucratic structures as fundamentally sound and simply in need of some culling.

Sunstein suggests that “it might be acceptable or sensible to tolerate a delay” in normal times, but not in a pandemic. Tech investor Marc Andreessen sees a lack of national willpower, an unwillingness to grab hold of problems and build anew. Prominent observers such as Francis Fukuyama, George Packer and Ezra Klein blame a broken political system and a divided culture; they offer little hope for redemption, even with new leadership.

All misdiagnose what caused government to fail here, and they confuse causes with what are more likely symptoms. Fukuyama rightly identifies a critical void in American political culture: the loss of a high “degree of trust that citizens have in their government,” which countries like Germany and South Korea enjoy. But why have Americans lost trust in their government?

No doubt, after this is all over, a report will catalog the errors and misjudgments that allowed COVID-19 to shut down America. The report will likely begin years back, when officials refused to heed warnings about pandemic planning. It will expose the wishful thinking of President Trump, who for almost two months said that the coronavirus was “totally under control.” Errors of judgment like these are inevitable, to some degree—they happened during Pearl Harbor and 9/11, too—and with luck, they will inform future planning. The light will then shine on the operating framework of modern government, revealing not mainly errors of judgment, or cultural divisions, but a tangle of red tape that causes failure. At every step, officials and public-health professionals were prevented from making vital choices by legal obstacles.

Andreessen is correct that Americans have lost the spirit to build, but that’s because we’re not allowed to build. A governing structure that takes upward of a decade to approve an infrastructure project and ranks 55th in World Bank assessments for “ease of starting a business” does not encourage individual and institutional initiative. Of course Americans don’t trust government—it gets in the way of their daily choices, even as it fails to meet many national needs.

Our response to the COVID-19 missteps should not be to wring our hands about our miserable political system, or about the cynicism and selfishness that have infected our culture. We should focus on why government fails in making daily choices. What many Americans see clearly—but most public intellectuals cannot see—is a system that prevents people from acting on their best judgment. By re-empowering officials to do what they think is right, we may also reinvigorate American culture and democracy.

The root cause of failed government is structural paralysis. What’s surprising about the tragic mishaps in dealing with COVID-19 is how unsurprising they were to the teachers, nurses, and local officials who are continually stymied by bureaucratic rules. A few years ago, a tree fell into a creek in Franklin Township, New Jersey, and caused flooding. A town official sent a backhoe to pull it out. But then someone, probably the town lawyer, pointed out that a permit was required to remove a natural object from a “Class C-1 Creek.” It took the town almost two weeks and $12,000 in legal fees to remove the tree.

In January, University of Washington epidemiologists were hot on the trail of COVID-19. Virologist Alex Greninger had begun developing a test soon after Chinese officials published the viral genome. But while the coronavirus was in a hurry, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was not. Greninger spent 100 hours filling out an application for an FDA “emergency-use authorization” (EUA) to deploy his test in-house. He submitted the application by email. Then he was told that the application was not complete until he mailed a hard copy to the FDA Document Control Center. After a few more days, FDA officials told Greninger that they would not approve his EUA until he verified that his test did not cross-react with other viruses in his lab, and until he agreed also to test for MERS and SARS. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) then refused to release samples of SARS to Greninger because it’s too virulent. Greninger finally got samples of other viruses that satisfied the FDA. By the time they arrived, and his tests began, in early March, the outbreak was well on its way.

Regulatory tripwires continually hampered those dealing with the spreading virus. Hospitals learned that they couldn’t cope except by tossing out the rulebooks; other institutions weren’t so lucky. For example, after schools were shut down, needy students no longer had meals. Katie Wilson, executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance and a former Obama administration official, secured an agreement in principle to transfer federal meal funding to a program that provides meals during summer months. But red tape required a formal waiver from each state, which in turn required formal waivers from Washington. The bureaucratic instinct was relentless: school districts in Oregon were first required to “develop a plan as to how they are going to target the most-needy students.” Meantime, the children got no meals. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens, interviewing Wilson, summarized her plea to government: “Stop getting in the way.”

What’s needed to pull the tree out of the creek is no different than what’s needed to feed school kids: responsible people with the authority to act. They can be accountable for what they do and how well they do it, but they can’t succeed if they must continually pass through the eye of the bureaucratic needle.

Reformers are looking in the wrong direction. Electing new leaders won’t liberate Americans to take initiative. Nor is “deregulation” generally the solution for inept government; the free market won’t protect us against pandemics. The only solution is to replace the current operating system with a framework that empowers people again to take responsibility. We must reregulate, not deregulate.

American government rebuilt itself after the 1960s on the premise of avoiding human error by replacing human choice. That’s when we got the innovation of thousand-page rulebooks dictating the one-correct-way to do things. We mandated legal hearings for ordinary supervisory choices, such as maintaining order in classrooms or evaluating employees. We replaced human judgment with rules and objective proof. Finally, government would be pure—almost like a software program. Just follow the rules.

For 50 years, legislative and administrative law has piled up, causing public paralysis and private frustration. Almost no one has questioned why government prevents people from using their common sense. Conservatives misdiagnose the flaw as too much government; liberals resist any critique of public programs, assuming that any reform is a pretext for deregulation. In the recent Democratic presidential debates, no one asked how to make government work better.

Experts have it backward. Polarized politics, they say, causes public paralysis. While hyper-partisanship certainly paralyzes legislative activity, the bureaucratic idiocies that delayed everything from Covid-19 testing to school meals had nothing to do with politics. Paralysis of the public sector came first, leading to polarized politics. By the 1990s, broad public frustration with suffocating government fueled the rise of Newt Gingrich.

The growth of red tape made it hard to make anything work sensibly. Schools became anarchic; health-care bureaucracy caused costs to skyrocket; getting a permit could require a decade; and Big Brother was always hovering. Is your paperwork in order? Americans kept electing people who promised to fix it—the “Contract with America,” “Change we can believe in,” and “Drain the swamp”—but government was beyond the control of those elected to lead it. What happens when politicians give up on fixing things? They compete by pointing fingers—“It’s your fault!”—and resort to Manichean theories and identity-based villains. Public disempowerment breeds extremism.

A functioning democracy requires the bureaucratic machine to return to officials and citizens the authority needed to do their jobs. That necessitates a governing framework of goals and principles that re-empowers Americans to take responsibility for results. Giving officials, judges, and others the authority to act in accord with reasonable norms is what liberates everyone else to act sensibly. Students won’t learn unless the teacher maintains order in the classroom. New ideas by a teacher or parent go nowhere if the principal lacks the authority to act on them. To get a permit in timely fashion, the permitting official must have authority to decide how much review is needed. To enforce codes of civil discourse—and not allow a small group of students to bully everyone else—university administrators must have authority to sanction students who refuse to abide by the codes. To prevent judicial claims from becoming weapons of extortion, judges must have authority to determine their reasonableness. To contain a virulent virus, public-health officials must have authority to respond quickly.

Giving officials the needed authority does not require trust of any particular person. What’s needed is to trust the overall system and its hierarchy of accountability—as, for example, most Americans trust the protections and lines of accountability provided by the Constitution. There’s no detailed rule or objective proof that determines what represents an “unreasonable search and seizure” or “freedom of speech.” Those protections are nonetheless reliably applied by judges who, looking to guiding principles and precedent, make a ruling in each disputed situation.

The post-1960s bureaucratic state is built on flawed assumptions about human accomplishment. There is no “correct” way of meeting goals that can be dictated in advance. Nor can good judgment be proved by some objective standard or metric. Judgments can readily be second-guessed, as appellate courts review lower-court decisions, but the rightness of action almost always involves perception and values. That’s the best we can do.

The failure of modern government is not merely a matter of degree—of “too much red tape.” Its failure is inherent in the premise of trying to create an automatic framework that is superior to human choice and judgment. We thought we could input the facts and, as Czech playwright and statesman Vaclav Havel once parodied it, “a computer . . . will spit out a universal solution.” Trying to reprogram this massive, incoherent system is like putting new software onto a melted circuit board. Each new situation will layer new rules onto ones already short-circuiting.

Nothing much will work sensibly until we replace tangles of red tape with simpler, goal-oriented frameworks activated by human beings. This is a key lesson of the Covid-19 crisis. It’s time to reboot our governing system to let Americans take responsibility again.

Philip K. Howard, a lawyer, writer, photographer and New York City civic leader, is founder of Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left. This piece first ran in citylab.com

Philip K. Howard: Create panel to streamline government in wake of virus, including fixing extreme pensions, work rules

Worker disinfects a New York City subway car in the current pandemic. New York State’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority operations are rife with astronomically expensive and outdated work rules and extravagant pensions. Ditto at the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

NEW YORK

Howls of outrage greeted Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s (R.-Ky.) suggestion that Congress should resist further funding of insolvent state and local governments because the money would be used “to bail out state pensions” that were never affordable except “by borrowing money from future generations.” Instead, Senator McConnell suggested, perhaps Congress should pass a law allowing states to declare bankruptcy.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo immediately countered that the bankruptcy of a large state would lead to fiscal chaos, and called McConnell’s suggestion “one of the saddest, really dumb comments of all time.”

Indeed, the lesson of the 2008 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy was that a bail-out would have been far preferable, less costly as well as less disruptive to markets.

But McConnell is correct that many states are fiscally underwater because of irresponsible giveaways to public unions. About 25 percent of the Illinois state budget goes to pensions, including more than $100,000 annually to 19,000 pensioners, who retired, on average, at age 59. These pensions were often inflated by gimmicks such as spiking overtime in the last years of employment, or by working one day to get credit for an extra year.

In New York, arcane Metropolitan Transportation Authority work rules result in constant extra pay — including an extra day’s pay if a commuter rail engineer drives both a diesel and an electric train; two months of paid vacation, holiday and sick days; and overtime for workdays longer than eight hours even if part of a 40-hour week. In 2019, the MTA paid more than $1 billion in overtime.

Cuomo has thrown out rulebooks to deal with COVID-19, and recently mused about the need to clean house: “How do we use this situation and …reimagine and improve and build back better? And you can ask this question on any level. How do we have a better transportation system, a …better public health system… You have telemedicine that we have been very slow on. Why was everybody going to a doctor's office all that time? Why didn't you do it using technology? … Why haven't we incorporated so many of these lessons? Because change is hard, and people are slow. Now is the time to do it.”

Cut red tape, reform entitlements

Perhaps McConnell and Cuomo are not that far apart after all. While bankruptcy makes no sense now, since states can hardly be blamed for COVID-19, federal funding could come with an obligation by states to adopt sustainable benefits and work practices for public employees.

Why should taxpayers pay for indefensible entitlements? How can Cuomo run “a better transportation system” when rigid work rules prohibit him from making sensible operational choices?

Taxpayers are reeling from these indefensible burdens. The excess baggage in public institutions is hardly limited to public employees. The ship of state founders under the heavy weight of red tape and entitlements that have, at best, only marginal utility to current needs.

Bureaucratic paralysis is the norm, whether to start a new business (the U.S. ranks 55th in World Bank ratings) or to act immediately when a virulent virus appears (public health officials in Seattle were forced to wait for weeks for federal approvals).

Well-intended programs from past decades have evolved into inexcusable entitlements today — such as “carried interest” tax breaks to investment firms and obsessive perfection mandated by special-education laws (consuming upward of a third of school budgets).

Partisanship blocks reform

Government needs to become disciplined again, just as in wartime. It must be adaptable, and encourage private initiative without unnecessary frictions. Dense codes should be replaced with simpler goal-oriented frameworks, as Cuomo has done. Red tape should be replaced with accountability. Excess baggage should be tossed overboard. We’re in a storm, and can’t get out while wallowing under the heavy weight of legacy practices and special privileges.

McConnell and Cuomo each have identified the madness of tolerating public-waste-as-usual. But toxic partisanship drives them apart. Nor would ad hoc negotiations work to restore discipline to government; too many interest groups feast at the public trough.

The only practical approach is for Congress to authorize an independent recovery commission with a broad mandate to relieve red tape and recommend ways to clean out unnecessary costs and entitlements. This is the model of “base-closing commissions” that make politically difficult choices of which states lose military bases.

Recovering from this crisis will be difficult enough without lugging along the accumulated baggage from the past. A streamlined, disciplined government would be a godsend not only to marshal resources for social needs, but to liberate human initiative at every level of society. That requires changing the rules. But change is hard, as Cuomo noted. Broad trust will be needed. That’s why the new framework should be devised by an independent recovery commission. =

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, writer, civic leader and photographer, is founder of Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward. This piece first ran in USA Today.

Campaign for Common Sense

Watch for action by the new national reform project called Campaign for Common Sense, started by the legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good. The project’s Web site will be up soon. One of the organization’s key goals is to start rebuilding America’s crumbling infrastructure by cutting red tape.