Michelle Andrews: In pandemic, many employers have expanded mental-health coverage

In group therapy

As the COVID-19 pandemic burns through its second year, the path forward for American workers remains unsettled, with many continuing to work from home while policies for maintaining a safe workplace evolve. In its 2021 Employer Health Benefits Survey, released Nov. 20, KFF found that many employers have ramped up mental health and other benefits to provide support for their workers during uncertain times.

See Rhode Island organization’s role below.

Meanwhile, the proportion of employers offering health insurance to their workers remained steady, and increases for health-insurance premiums and out-of-pocket health expenses were moderate, in line with the rise in pay. Deductibles were largely unchanged from the previous two years.

“With the pandemic, I’m not sure that employers wanted to make big changes in their plans, because so many other things were disrupted,” said Gary Claxton, a senior vice president at KFF and director of the Health Care Marketplace Project. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

Reaching out to a dispersed workforce is also a challenge, with on-site activities like employee benefits fairs curtailed or eliminated.

“It’s hard to even communicate changes right now,” Claxton said.

Many employers reported that since the pandemic started they’ve made changes to their mental-health and substance-use benefits. Nearly 1,700 nonfederal public and private companies completed the full survey.

At companies with at least 50 workers, 39% have made such changes, including:

31% that increased the ways employees can tap into mental-health services, such as telemedicine.

16% that offered employee assistance programs or other new resources for mental health.

6% that expanded access to in-network mental health providers.

4% that reduced cost sharing for such visits.

3% that increased coverage for out-of-network services.

Workers are taking advantage of the services. Thirty-eight percent of the largest companies with 1,000 or more workers reported that their workers used more mental health services in 2021 than the year before, while 12% of companies with at least 50 workers said their workers upped their use of mental health services.

Thundermist Health Center is a federally qualified health center that serves much of Rhode Island. (It’s based in Woonsocket.) The center’s health plan offers employees an HMO and a preferred provider organization, and 227 workers are enrolled.

When the pandemic hit, the health plan reduced the co-payments for behavioral health visits to zero from $30.

“We wanted to encourage people to get help who were feeling any stress or concerns,” said Cynthia Farrell, associate vice president for human resources at Thundermist.

Once the pandemic ends, if the health center adds a co-payment again, it won’t be more than $15, she said.

The pandemic also changed the way many companies handled their wellness programs. More than half of those with at least 50 workers expanded these programs during the pandemic. The most common change? Expanding online counseling services, reported by 38% of companies with 50 to 199 workers and 58% of companies with 200 or more workers. Another popular change was expanding or changing existing wellness programs to meet the needs of people who are working from home, reported by 17% of the smaller companies and 34% of the larger companies that made changes.

Beefing up telemedicine services was a popular way for employers to make services easier to access for workers, who may have been working remotely or whose clinicians, including mental-health professionals, may not have been seeing patients in person.

In 2021, 95% of employers offered at least some health care services through telemedicine, compared with 85% last year. These were often video appointments, but a growing number of companies allowed telemedicine visits by telephone or other communication modes, as well as expanded the number of services offered this way and the types of providers that can use them.

About 155 million people in the U.S. have employer-sponsored health care. The pandemic didn’t change the proportion of employers that offered coverage to their workers: It has remained mostly steady at 59% for the past decade. Size matters, however, and while 99% of companies with at least 200 workers offers health benefits, only 56% of those with fewer than 50 workers do so.

In 2021, average premiums for both family and single coverage rose 4%, to $22,221 for families and $7,739 for single coverage. Workers with family coverage contribute $5,969 toward their coverage, on average, while those with single coverage pay an average of $1,299.

The annual premium change was in line with workers’ wage growth of 5% and inflation of 1.9%. But during the past 10 years, average premium increases have substantially exceeded increases in wages and inflation.

Workers pay 17% of the premium for single coverage and 28% of that for family coverage, on average. The employer pays the rest.

Deductibles have remained steady in 2021. The average deductible for single coverage was $1,669, up 68% over the decade but not much different from the previous two years, when the deductible was $1,644 in 2020 and $1,655 in 2019.

Eighty-five percent of workers have a deductible now; 10 years ago, the figure was 74%.

Health-care spending has slowed during the pandemic, as people delay or avoid care that isn’t essential. Half of large employers with at least 200 workers reported that health-care use by workers was about what they expected in the most recent quarter. But nearly a third said that utilization has been below expectations, and 18% said it was above it, the survey found.

At Thundermist Health Center, fewer people sought out health care last year, so the self-funded health plan, which pays employee claims directly rather than using insurance for that purpose, fell below its expected spending, Farrell said.

That turned out to be good news for employees, whose contribution to their plan didn’t change.

“This year was the first year in a very long time that we didn’t have to change our rates,” Farrell said.

The survey was conducted between January and July 2021. It was published in the journal Health Affairs and KFF also released additional details in its full report.

Michelle Andrews is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Woonsocket's city hall

—Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Rachel Bluth: CVS comes under fire for low nursing-home vaccination rates

CVS store in Coventry, Conn.

— Photo by JJBers

The effort to vaccinate some of the country’s most vulnerable residents against COVID-19 has been slowed by a federal program that sends retail pharmacists into nursing homes — accompanied by layers of bureaucracy and logistical snafus.

As of Jan. 14, more than 4.7 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna covid vaccines had been allocated to the federal pharmacy partnership, which has deputized pharmacy teams from Deerfield, Ill.-based Walgreens and Woonsocket, R.I.-based CVS to vaccinate nursing home residents and workers. Since the program started in some states on Dec. 21, however, they have administered about a quarter of the doses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Across America, some nursing-home directors and health-care officials say the partnership is actually hampering the vaccination process by imposing paperwork and cumbersome corporate policies on facilities that are thinly staffed and reeling from the devastating effects of the coronavirus. They argue that nursing homes are unique medical facilities that would be better served by medical workers who already understand how they operate.

Mississippi’s state health officer, Dr. Thomas Dobbs, said the partnership “has been a fiasco.”

The state has committed 90,000 vaccine doses to the effort, but the pharmacies had administered only 5 percent of those shots as of Jan. 14, Dobbs said. Pharmacy officials told him they’re having trouble finding enough people to staff the program.

Dobbs pointed to neighboring Alabama and Louisiana, which he says are vaccinating long-term care residents at four times the rate of Mississippi.

“We’re getting a lot of angry people because it’s going so slowly, and we’re unhappy too,” he said.

Many of the nursing homes that have successfully vaccinated willing residents and staff members are doing so without federal help.

For instance, Los Angeles Jewish Home, with roughly 1,650 staff members and 1,100 residents on four campuses, started vaccinating Dec. 30. By Jan. 11, the home’s medical staff had administered its 1,640th dose. Even the facility’s chief medical director, Noah Marco, helped vaccinate.

The home is in Los Angeles County, which declined to participate in the CVS/Walgreens program. Instead, it has tasked nursing homes with administering vaccines themselves, and is using only Moderna’s easier-to-handle product, which doesn’t need to be stored at ultracold temperatures, like the Pfizer vaccine. (Both vaccines require two doses to offer full protection, spaced 21 to 28 days apart.)

By contrast, Mariner Health Central, which operates 20 nursing homes in California, is relying on the federal partnership for its homes outside of L.A. County. One of them won’t be getting its first doses until next week.

“It’s been so much worse than anybody expected,” said the chain’s chief medical officer, Dr. Karl Steinberg. “That light at the end of the tunnel is dim.”

Nursing homes have experienced some of the worst outbreaks of the pandemic. Though they house less than 1 percent of the nation’s population, nursing homes have accounted for 37 percent of deaths, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Facilities participating in the federal partnership typically schedule three vaccine clinics over the course of nine to 12 weeks. Ideally, those who are eligible and want a vaccine will get the first dose at the first clinic and the second dose three to four weeks later. The third clinic is considered a makeup day for anyone who missed the others. Before administering the vaccines, the pharmacies require the nursing homes to obtain consent from residents and staffers.

Despite the complaints of a slow rollout, CVS and Walgreens said that they’re on track to finish giving the first doses by Jan. 25, as promised.

“Everything has gone as planned, save for a few instances where we’ve been challenged or had difficulties making contact with long-term care facilities to schedule clinics,” said Joe Goode, a spokesperson for CVS Health.

Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, acknowledged some delays through the partnership, but said that’s to be expected because this kind of effort has never before been attempted.

“There’s a feeling they’ll get up to speed with it and it will be helpful, as health departments are pretty overstretched,” Plescia said.

But any delay puts lives at risk, said Dr. Michael Wasserman, the immediate past president of the California Association of Long Term Care Medicine.

“I’m about to go nuclear on this,” he said. “There should never be an excuse about people not getting vaccinated. There’s no excuse for delays.”

Bringing in Vaccinators

Nursing homes are equipped with resources that could have helped the vaccination effort — but often aren’t being used.

Most already work with specialized pharmacists who understand the needs of nursing homes and administer medications and yearly vaccinations. These pharmacists know the patients and their medical histories, and are familiar with the apparatus of nursing homes, said Linda Taetz, chief compliance officer for Mariner Health Central.

“It’s not that they aren’t capable,” Taetz said of the retail pharmacists. “They just aren’t embedded in our buildings.”

If a facility participates in the federal program, it can’t use these or any other pharmacists or staffers to vaccinate, said Nicole Howell, executive director for Ombudsman Services of Contra Costa, Solano and Alameda counties.

But many nursing homes would like the flexibility to do so because they believe it would speed the process, help build trust and get more people to say yes to the vaccine, she said.

Howell pointed to West Virginia, which relied primarily on local, independent pharmacies instead of the federal program to vaccinate its nursing home residents.

The state opted against the partnership largely because CVS/Walgreens would have taken weeks to begin shots and Republican Gov. Jim Justice wanted them to start immediately, said Marty Wright, CEO of the West Virginia Health Care Association, which represents the state’s long-term care facilities.

The bulk of the work is being done by more than 60 pharmacies, giving the state greater control over how the doses were distributed, Wright said. The pharmacies were joined by Walgreens in the second week, he said, though not as part of the federal partnership.

“We had more interest from local pharmacies than facilities we could partner them up with,” Wright said. Preliminary estimates show that more than 80% of residents and 60% of staffers in more than 200 homes got a first dose by the end of December, he said.

Goode from CVS said his company’s participation in the program is being led by its long-term-care division, which has deep experience with nursing homes. He noted that tens of thousands of nursing homes — about 85 percent nationally, according to the CDC — have found that reassuring enough to participate.

“That underscores the trust the long-term care community has in CVS and Walgreens,” he said.

Vaccine recipients don’t pay anything out-of-pocket for the shots. The costs of purchasing and administering them are covered by the federal government and health insurance, which means CVS and Walgreens stand to make a lot of money: Medicare is reimbursing $16.94 for the first shot and $28.39 for the second.

Bureaucratic Delays

Technically, federal law doesn’t require nursing homes to obtain written consent for vaccinations.

But CVS and Walgreens require them to get verbal or written consent from residents or family members, which must be documented on forms supplied by the pharmacies.

Goode said consent hasn’t been an impediment so far, but many people on the ground disagree. The requirements have slowed the process as nursing homes collect paper forms and Medicare numbers from residents, said Tracy Greene Mintz, a social worker who owns Senior Care Training, which trains and deploys social workers in more than 100 facilities around California.

In some cases, social workers have mailed paper consent forms to families and waited to get them back, she said.

“The facilities are busy trying to keep residents alive,” Greene Mintz said. “If you want to get paid from Medicare, do your own paperwork,” she suggested to CVS and Walgreens.

Scheduling has also been a challenge for some nursing homes, partly because people who are actively sick with covid shouldn’t be vaccinated, the CDC advises.

“If something comes up — say, an entire building becomes covid-positive — you don’t want the pharmacists coming because nobody is going to get the vaccine,” said Taetz of Mariner Health.

Both pharmacy companies say they work with facilities to reschedule when necessary. That happened at Windsor Chico Creek Care and Rehabilitation in Chico, Calif., where a clinic was pushed back a day because the facility was awaiting covid test results for residents. Melissa Cabrera, who manages the facility’s infection control, described the process as streamlined and professional.

In Illinois, about 12,000 of the state’s roughly 55,000 nursing home residents had received their first dose by Sunday, mostly through the CVS/Walgreens partnership, said Matt Hartman, executive director of the Illinois Health Care Association.

While Hartman hopes the pharmacies will finish administering the first round by the end of the month, he noted that there’s a lot of “headache” around scheduling the clinics, especially when homes have outbreaks.

“Are we happy that we haven’t gotten through round one and West Virginia is done?” he asked. “Absolutely not.”

Rachel Bluth is a Kaiser Health News correspondent.

Rachel Bluth: rbluth@kff.org, @RachelHBluth

KHN correspondent Rachana Pradhan contributed to this report.

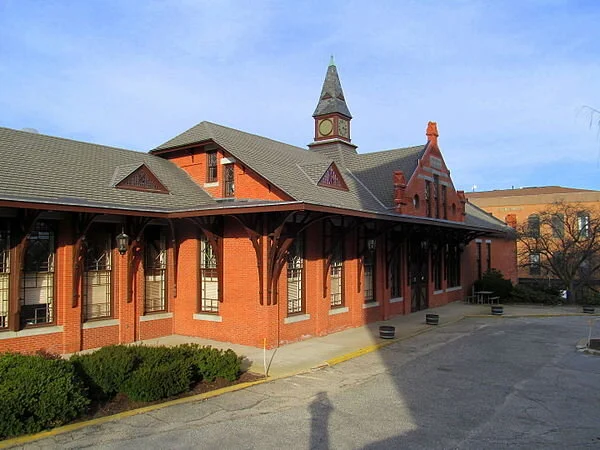

Better than driving on Route 146, especially in winter

Woonsocket train depot

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Let’s hope that Boston Surface Rail Co. can settle its dispute with the Rhode Island Department of Transportation over the company’s use of the historic train depot (built in 1882!) in Woonsocket and be able to start passenger rail service (and bus service to supplement it) between that city and Worcester sometime next year. It would be one of America’s first private passenger rail companies since the creation of quasi-public Amtrak, in 1971.

The service would be a boon to those who want to stay off crowded Route 146, in the Providence-Worcester corridor, and serve an area now with very thin public transportation. And consider that huge CVS is based in Woonsocket; more than a few of its employees would be happy to use public transportation.

Remember that Greater Providence is the second-largest metro area in New England, after Boston, and Worcester proper the second-largest city; Providence proper is the third-largest.

Anything to get more people off the roads between Greater Providence and Worcester would he most appreciated! The service would be particularly appreciated in the winter: The area crossed by Route 146, being fairly high (by New England standards) and well inland, gets lots of snow most winters.

Boston Surface Rail asserts that the Rhode Island Department of Transportation has been difficult to deal with. RIDOT should prioritize improving non-car travel in this important corridor. Why is it that it seems so difficult to get new projects launched in the Ocean State?

To read GoLocal’s story on this, please hit this link.

xxx

Robert Whitcomb: Private-sector passenger rail?

Since the disappearance of private-sector passenger rail service decades ago, intrepid entrepreneurs have tried to bring it back. None have succeeded.

However, in some densely populated places, passenger rail has even thrived in the public sector, at least as measured by passenger volume. This mostly means Amtrak in the Northeast Corridor and several major cities’ long-established commuter-rail networks. But new commuter rail is also catching on in some unlikely places, including such Sunbelt cities as Dallas and Phoenix, which now have popular light-rail systems.

Now, with an aging population, the proliferation of digital devices that many people would prefer to stare at rather than at the road and the increasing unpleasantness of traveling on America’s decaying highway infrastructure amidst texting and angry drivers, private passenger rail looks more capitalistically attractive.

Consider All Aboard Florida, a company that plans to offer extensive rail service starting in 2017. It will connect Miami and Orlando in just under three hours, with stops in Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach.

Its advertising copy eloquently describes commuter rail’s allure in populous areas: “{Y}ou can turn your stressful daily {car} commute into a productive or peaceful time by choosing to take the train instead of driving your car. By becoming a train commuter, you’ll also help the economy and environment while you’re at it.’’

Southern New England, like much of Florida, is densely populated, with some unused or underused rail rights of way. So our entrepreneurs occasionally propose private passenger rail for routes not served by Amtrak or such regional mass-transit organizations as Metro North and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

Consider the Worcester-Providence route, on which a new company called the Boston Surface Railroad Co. wants to start operating commuter rail service in 2017 on the (now freight-only) Providence and Worcester Railroad’s tracks. Most of the commuters going to work would be traveling from the Worcester area, via Woonsocket, where there would be a stop, to Greater Providence. While Providence itself has fewer people -- about 178,000 -- than Worcester (about 183,000), the two-state Providence metro area -- about 1.6 million -- is much bigger than the latter’s metro area’s about 813,000.

The density is there for rail service. That the region has an older population than the national average and frequent bad winter weather also give the idea a lift.

But the old rail line needs to be upgraded if the trips are to be made fast enough to lure many travelers. The company hopes to offer a one-way time of about 70 minutes on a route that you can drive in about 45 minutes in moderate traffic and clement weather. That could be a killer.

What this project and similar ones need is new welded track, rebuilt rail beds (with help of public money?) and some entirely new routes to make service competitive with car-driving times. We need more passenger and duel-purpose passenger-freight rail lines, not more highways. But getting them will be tough in a country that so blithely tolerates crumbling transportation infrastructure and has a deeply entrenched libertarian commuting habit of a single person driving long distances to work. Unless gasoline tops $5 a gallon and stays there for at least a year, it’s hard to see millions of Americans deciding that they’ll quit their cars to take the train.

Still, I applaud the project’s CEO, Vincent Bono, and hope that thousands of commuters will give his railroad a try. While the trip would be long, think of how much uninterrupted Web surfing (free Wi-Fi!), reading and snoozing you could get on these trains, with their reclining seats.

xxx

An Aug. 10 USA Today story was headlined “Smaller cities emerge among top picks for biz meetings.’’ Depressingly, Providence was not on the list of the top 50 places for “meetings and events’’ in 2015, say evaluations by Cvent. But many far less interesting and attractive places were.

The reasons probably include Rhode Island’s under-funded and balkanized self-promotion and the long delay (now finally being addressed) in building a longer runway at T.F. Green Airport.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), a Providence-based editor, writer and consultant, oversees newenglanddiary.com and is a partner in Cambridge Management Group, (cmg625.com), a healthcare consultancy, and a fellow at the Pell Center. He used to be the editorial-page editor of The Providence Journal and the finance editor of the International Herald Tribune, among other jobs.