William T. Hall: Surviving the swarm

Text and watercolor painting by William T. Hall, a Florida-and-New England-based painter and writer

As we endured one of our family weeding sessions in our vegetable garden in Thetford, Vt., my grandfather said abruptly, and with strong emphasis, the four-letter “S-word”. It was enough of a surprise to lead grandmother to remind him that children were present. “Jesus, Mary and Joseph, Harold, your language – please!”

We all stared at Gramps as Grandmother looked over her glasses at my mother, who was smiling at her while fighting with a deep-set weed. Mother’s garden glove was full of a dozen or so vanquished weed specimens dropping dust as she looked over to me, rolling her eyes. I could see my reflection in her sunglasses as my little brother, Steve, leaned in and whispered to me , while wagging his index finger at the ground, “Naughty-naughty, Gramps”

“What’s wrong, Dad?” my mother asked. “You okay?”, she asked, as she pulled on another stubborn weed.

He said nothing as he set his jaw and unfolded his tall frame upward from his kneeling position like a camel standing up in the desert. He was looking at the top of his wrist as if to check a watch that wasn’t there. In that hand he held a big red Folger’s coffee can half-filled with kerosene into which he had been dropping hundreds of Japanese Beetles. These he had picked meticulously from the leaves of his potato plants. This sort of thing defined one of his methods for guarding against pests in the modern age of pesticides. “Better to pick’m off and get’m before they get you.”

After he had stood up fully, he looked perplexed, as if he didn’t believe what had just happened. He looked at my grandmother and said one word,

“Bee.”

“Sting?“ My mother asked.

“No he just scratched me a — warning”.

This we all knew from being on the farm. When you work around bees they are busy, too, gathering honey. Unless you create too much commotion around bees or otherwise make them too anxious, a human usually gets a (warning) a scratch before a (sting).

A warning was when a bee dragged his stinger across your skin to give you what felt like a little hot spark. A full “sting” was, of course, much more painful and was delivered with a bee’s ultimate strength, resulting in the hooked end of the stinger deep under the skin with the bee’s abdomen still attached to feed the stinger with venom. This added to your pain immensely. For this one extreme act, the honeybee pays with its life, and for allergic recipients, the sting can cause anaphylactic shock. To that person multiple stings all at once could cause death.

To my grandfather this “scratch” seemed like an unprovoked over-reaction, and he didn’t understand what he had done to deserve it.

Harold had been stung several times in his life but he understood that each time he’d done something provocative. When he saw that there were lots of other bees around us not harming us, it seemed as if nothing menacing had happened, so what was the big deal? Grandpa was insulted. He shook his head. My mother, teasing her father, asked him, “Dad, did you make a mistake? You know the difference between a Japanese beetle and a bee right”?

We all laughed and looked at my grandfather, wanting to gauge his reaction to my mother’s tease. He held the coffee can in one hand and laughed politely at the ribbing. He was always a good sport.

“I’m glad I didn’t sit on him”, he said and got a double-good laugh from all of us.

But as he was looking at us he was still wondering why there seemed to be so many bees everywhere in the air. They swirled like embers from a campfire. It was a busy confusion in orange, black and tan reminding him of when he attended his mother’s beehives at their turkey farm in Walpole, Mass., years before.

“Gramps! What’s is that?” asked my brother Steve he excitedly pointed to the sky above and behind Gramp’s silhouetted upper torso.

“Harold!” My grandmother shouted sharply, my grandfather and the sky above him reflecting in her glasses.…

Gramps looked at her perplexed as he turned to see what she meant. Something amazing and frightening was happening in the sky behind him. He had never seen anything like it before, and nor would he ever again. He looked back in awe at a jet-black roiling cloud in the sky over the Connecticut River. “It’s bees!”Then suddenly,“ SWARM!” he yelled as he set down his coffee can.

“What the heck!?” My mother exclaimed as she stood up, dropping her spade and the weeds from her gloves.

“Gloria, Quick help me up!” my grandmother yelled. My mother said frantically, in a commanding voice, to Steve and me, “Kids, get your grandmother up and head to the house”! As we helped our 200-pound grandmother to her feet, our mother rushed to her father’s side asking. “What should we do? Dad?”

They both looked up at the cloud and now we all could hear the sound of the bees, which mimicked the sound of a breeze blowing through tree leaves.

My grandfather mumbled something unintelligible in Swedish under his breath.

“Pop, in English!”, my mother asked in a slightly panicked tone. “What should we do?”

Without taking his eyes off the swarm, Gramp said, “Yes, get Lillian to the house, but don’t run, Ok? Just walk fast and don’t panic. We must not spook the swarm. Look at them! They look pretty riled alread.”

“Harold, you be careful,’’ my grandmother said.

“We’ll be fine, ’’ he said.

“Somewhere in the middle of the swirling mass is the Queen. Bees will do anything to protect their Queen. They’re looking for a new hive. These other bees down here are the scouts”.

Our farm was on the floor of Vermont’s Upper Connecticut River Valley about a football field’s length from the river and a mile’s south of the village center of Thetford. Our barn was in the middle of our property between two 25-acre fields, with two big shade-maple trees taller than any other trees next to the barn, which was four stories tall, from the basement to the peak of the open hayloft.

The whole barn structure was basically open. It was June, and the barn was empty of hay. There was one window in the peak and an open hay door in the end. The barn was designed to suck air in at the basement pig stalls on the backside of the building and to direct it inward and upward out through the big open barn doors and hay doors in both peaks. Those doors were 16 feet tall and were at the top of the earthen ramp that led to the second story. The ramp was designed for horses pulling full hay-wagons up into the big main hay-storage room. The main room was enormous, about 40 by 60 feet and 45 feet to the peak, where the hay trolley track and unloading-fork still hung covered in cobwebs.

Grandpa knew that the swarm of bees high in the air above our barn probably saw what looked like the perfect place for new beehive — a place with the perfect size and shape to house what seemed like a zillion tired and desperate bees and their queen.

My grandfather could see this in the few moments he had to scope out the problem and he understood that the welcome mat would be out until he could close up the barn to keep out these unwelcome guests.

Gramps now could hear the house windows being slammed down shut and the garage door being closed in the long shed off the main house. The ladies had done their job. The house would be a secure hiding place for the family no matter what happened in the other buildings. Grandpa’s carpentry shop, the hen house, a little stone milk-house and our barn were the only possible manmade homes for the bees.

The area directly above and behind the barn was a jet-black fuzzy moving mass. The swarm covered the whole width of the house, barn and shade trees. The scene reminded Gramps of the sand-and-soil clouds during the 1930’s Dust Bowl. Like those roiling clouds, the cloud of bees had a dark and menacing look.

Like a monster in the sky, the cloud seemed to lurch forward, north up the river, and then roll back on itself down the river as if there was dissension in the cloud of bees.

The air around us was still filled by a blizzard of bees, but even though we were occasionally scratched by the frantic scouting insects, we did not feel in danger. We could see their dilemma. We did not want to make their plight any worse than it was, but they could not have our barn, from which it would have taken months and lots of money to dislodge them. Worse, many bees would die in the removal. Maybe the bees could feel this, or maybe they were totally unaware of us, but they continued to leave us alone.

Gramps knew that with any flood of living things — humans, cattle, turkeys, fish and so on, only so many of them could get through a restricted opening at once without catastrophic results.

They had only their instinct to protect and nurture their queen. Each individual bee was devoted to its queen first, then secondly to the whole hive. Beyond that simple reality they had not evolved.

They were incapable of leaving her but confused about where to take her. At this point they seemed at a crossroads.

“Billy, go to the basement of the barn and close all the pig-pen doors down there,’’ Gramps told me. “Make sure the bees can’t get through any cracks. Throw hay at the bottom of the doors to close up the gap. Then meet me at the front ramp and we’ll close the big doors together. We can get to the windows last. Listen to me.…If this all turns bad, then get to the house and your mother will know what to do”.

“Where are you going, “ I asked.

“I’ll go to my shop and see if I can close it up. It’s wide open”.

“What about the chickens,” I asked.

“I don’t know? They eat bugs. They’ll have to fend for themselves”.

The cloud of bees was hanging over the rear pasture and getting closer to the barn by the minute, casting a dull shadow as when a cloud causes a shadow in the valley. I did get stung when I closed the last pig-pen door and I put my hand right on a bee. It hurt, but I sucked on the spot and kept moving.

When I got to the big doors in the front of the barn, grandfather was there. He’d rolled the burn-barrel up the ramp, saying that would be a last resort. He would start a smudge fire in the barrel to smoke out the incoming bees if it became necessary. The thought of any open fire in our barn made us both sick to think about. “Would you really risk that”, I asked my grandfather.

“No. I don’t think so, but we’ll see”.

As we rolled the barrel into place, something in the changing sky caused a shift on what had been sun-lit ground to scattered shadows there. With that change came a slight drop in temperature.

The moment seemed to signal something within the swarm. The bees moved. They roiled northward, and then suddenly their pace increased and they seemed to rise up farther. There was a bulge in the front of the cloud as it headed up river. The swarm passed over the iron bridge a half mile away at East Thetford and continued headed north, up the river. Where there had been millions of scouting bees at our farm, in a few minutes there were none.

The swarm eventually disappeared into far northwestern New Hampshire, where they were believed to have taken up residence in the stacked-up wrecked automobiles in a large junkyard abandoned years before, and then, finally, in spectacular Franconia Notch.

Little by little, one of those companies that catches and ships bees were able to capture many of the insects and transport them to areas of the U.S. that suffered from a deadly fungus that still endangers bee populations today.

Where the bees came from in such large numbers and why they took flight has never really been determined.

William T. Hall: Surviving the swarm

Text and watercolor painting by William T. Hall, a Florida-and-New England-based painter and writer

As we endured one of our family weeding sessions in our vegetable garden in Thetford, Vt., my grandfather said abruptly, and with strong emphasis, the four-letter “S-word”. It was enough of a surprise to lead grandmother to remind him that children were present. “Jesus, Mary and Joseph, Harold, your language – please!”

We all stared at Gramps as Grandmother looked over her glasses at my mother, who was smiling at her while fighting with a deep-set weed. Mother’s garden glove was full of a dozen or so vanquished weed specimens dropping dust as she looked over to me, rolling her eyes. I could see my reflection in her sunglasses as my little brother, Steve, leaned in and whispered to me , while wagging his index finger at the ground, “Naughty-naughty, Gramps”

“What’s wrong, Dad?” my mother asked. “You okay?”, she asked, as she pulled on another stubborn weed.

He said nothing as he set his jaw and unfolded his tall frame upward from his kneeling position like a camel standing up in the desert. He was looking at the top of his wrist as if to check a watch that wasn’t there. In that hand he held a big red Folger’s coffee can half-filled with kerosene into which he had been dropping hundreds of Japanese Beetles. These he had picked meticulously from the leaves of his potato plants. This sort of thing defined one of his methods for guarding against pests in the modern age of pesticides. “Better to pick’m off and get’m before they get you.”

After he had stood up fully, he looked perplexed, as if he didn’t believe what had just happened. He looked at my grandmother and said one word,

“Bee.”

“Sting?“ My mother asked.

“No he just scratched me a — warning”.

This we all knew from being on the farm. When you work around bees they are busy, too, gathering honey. Unless you create too much commotion around bees or otherwise make them too anxious, a human usually gets a (warning) a scratch before a (sting).

A warning was when a bee dragged his stinger across your skin to give you what felt like a little hot spark. A full “sting” was, of course, much more painful and was delivered with a bee’s ultimate strength, resulting in the hooked end of the stinger deep under the skin with the bee’s abdomen still attached to feed the stinger with venom. This added to your pain immensely. For this one extreme act, the honeybee pays with its life, and for allergic recipients, the sting can cause anaphylactic shock. To that person multiple stings all at once could cause death.

To my grandfather this “scratch” seemed like an unprovoked over-reaction, and he didn’t understand what he had done to deserve it.

Harold had been stung several times in his life but he understood that each time he’d done something provocative. When he saw that there were lots of other bees around us not harming us, it seemed as if nothing menacing had happened, so what was the big deal? Grandpa was insulted. He shook his head. My mother, teasing her father, asked him, “Dad, did you make a mistake? You know the difference between a Japanese beetle and a bee right”?

We all laughed and looked at my grandfather, wanting to gauge his reaction to my mother’s tease. He held the coffee can in one hand and laughed politely at the ribbing. He was always a good sport.

“I’m glad I didn’t sit on him”, he said and got a double-good laugh from all of us.

But as he was looking at us he was still wondering why there seemed to be so many bees everywhere in the air. They swirled like embers from a campfire. It was a busy confusion in orange, black and tan reminding him of when he attended his mother’s beehives at their turkey farm in Walpole, Mass., years before.

“Gramps! What’s is that?” asked my brother Steve he excitedly pointed to the sky above and behind Gramp’s silhouetted upper torso.

“Harold!” My grandmother shouted sharply, my grandfather and the sky above him reflecting in her glasses.…

Gramps looked at her perplexed as he turned to see what she meant. Something amazing and frightening was happening in the sky behind him. He had never seen anything like it before, and nor would he ever again. He looked back in awe at a jet-black roiling cloud in the sky over the Connecticut River. “It’s bees!”Then suddenly,“ SWARM!” he yelled as he set down his coffee can.

“What the heck!?” My mother exclaimed as she stood up, dropping her spade and the weeds from her gloves.

“Gloria, Quick help me up!” my grandmother yelled. My mother said frantically, in a commanding voice, to Steve and me, “Kids, get your grandmother up and head to the house”! As we helped our 200-pound grandmother to her feet, our mother rushed to her father’s side asking. “What should we do? Dad?”

They both looked up at the cloud and now we all could hear the sound of the bees, which mimicked the sound of a breeze blowing through tree leaves.

My grandfather mumbled something unintelligible in Swedish under his breath.

“Pop, in English!”, my mother asked in a slightly panicked tone. “What should we do?”

Without taking his eyes off the swarm, Gramp said, “Yes, get Lillian to the house, but don’t run, Ok? Just walk fast and don’t panic. We must not spook the swarm. Look at them! They look pretty riled alread.”

“Harold, you be careful,’’ my grandmother said.

“We’ll be fine, ’’ he said.

“Somewhere in the middle of the swirling mass is the Queen. Bees will do anything to protect their Queen. They’re looking for a new hive. These other bees down here are the scouts”.

Our farm was on the floor of Vermont’s Upper Connecticut River Valley about a football field’s length from the river and a mile’s south of the village center of Thetford. Our barn was in the middle of our property between two 25-acre fields, with two big shade-maple trees taller than any other trees next to the barn, which was four stories tall, from the basement to the peak of the open hayloft.

The whole barn structure was basically open. It was June, and the barn was empty of hay. There was one window in the peak and an open hay door in the end. The barn was designed to suck air in at the basement pig stalls on the backside of the building and to direct it inward and upward out through the big open barn doors and hay doors in both peaks. Those doors were 16 feet tall and were at the top of the earthen ramp that led to the second story. The ramp was designed for horses pulling full hay-wagons up into the big main hay-storage room. The main room was enormous, about 40 by 60 feet and 45 feet to the peak, where the hay trolley track and unloading-fork still hung covered in cobwebs.

Grandpa knew that the swarm of bees high in the air above our barn probably saw what looked like the perfect place for new beehive — a place with the perfect size and shape to house what seemed like a zillion tired and desperate bees and their queen.

My grandfather could see this in the few moments he had to scope out the problem and he understood that the welcome mat would be out until he could close up the barn to keep out these unwelcome guests.

Gramps now could hear the house windows being slammed down shut and the garage door being closed in the long shed off the main house. The ladies had done their job. The house would be a secure hiding place for the family no matter what happened in the other buildings. Grandpa’s carpentry shop, the hen house, a little stone milk-house and our barn were the only possible manmade homes for the bees.

The area directly above and behind the barn was a jet-black fuzzy moving mass. The swarm covered the whole width of the house, barn and shade trees. The scene reminded Gramps of the sand-and-soil clouds during the 1930’s Dust Bowl. Like those roiling clouds, the cloud of bees had a dark and menacing look.

Like a monster in the sky, the cloud seemed to lurch forward, north up the river, and then roll back on itself down the river as if there was dissension in the cloud of bees.

The air around us was still filled by a blizzard of bees, but even though we were occasionally scratched by the frantic scouting insects, we did not feel in danger. We could see their dilemma. We did not want to make their plight any worse than it was, but they could not have our barn, from which it would have taken months and lots of money to dislodge them. Worse, many bees would die in the removal. Maybe the bees could feel this, or maybe they were totally unaware of us, but they continued to leave us alone.

Gramps knew that with any flood of living things — humans, cattle, turkeys, fish and so on, only so many of them could get through a restricted opening at once without catastrophic results.

They had only their instinct to protect and nurture their queen. Each individual bee was devoted to its queen first, then secondly to the whole hive. Beyond that simple reality they had not evolved.

They were incapable of leaving her but confused about where to take her. At this point they seemed at a crossroads.

“Billy, go to the basement of the barn and close all the pig-pen doors down there,’’ Gramps told me. “Make sure the bees can’t get through any cracks. Throw hay at the bottom of the doors to close up the gap. Then meet me at the front ramp and we’ll close the big doors together. We can get to the windows last. Listen to me.…If this all turns bad, then get to the house and your mother will know what to do”.

“Where are you going, “ I asked.

“I’ll go to my shop and see if I can close it up. It’s wide open”.

“What about the chickens,” I asked.

“I don’t know? They eat bugs. They’ll have to fend for themselves”.

The cloud of bees was hanging over the rear pasture and getting closer to the barn by the minute, casting a dull shadow as when a cloud causes a shadow in the valley. I did get stung when I closed the last pig-pen door and I put my hand right on a bee. It hurt, but I sucked on the spot and kept moving.

When I got to the big doors in the front of the barn, grandfather was there. He’d rolled the burn-barrel up the ramp, saying that would be a last resort. He would start a smudge fire in the barrel to smoke out the incoming bees if it became necessary. The thought of any open fire in our barn made us both sick to think about. “Would you really risk that”, I asked my grandfather.

“No. I don’t think so, but we’ll see”.

As we rolled the barrel into place, something in the changing sky caused a shift on what had been sun-lit ground to scattered shadows there. With that change came a slight drop in temperature.

The moment seemed to signal something within the swarm. The bees moved. They roiled northward, and then suddenly their pace increased and they seemed to rise up farther. There was a bulge in the front of the cloud as it headed up river. The swarm passed over the iron bridge a half mile away at East Thetford and continued headed north, up the river. Where there had been millions of scouting bees at our farm, in a few minutes there were none.

The swarm eventually disappeared into far northwestern New Hampshire, where they were believed to have taken up residence in the stacked-up wrecked automobiles in a large junkyard abandoned years before, and then, finally, in spectacular Franconia Notch.

Little by little, one of those companies that catches and ships bees were able to capture many of the insects and transport them to areas of the U.S. that suffered from a deadly fungus that still endangers bee populations today.

Where the bees came from in such large numbers and why they took flight has never really been determined.

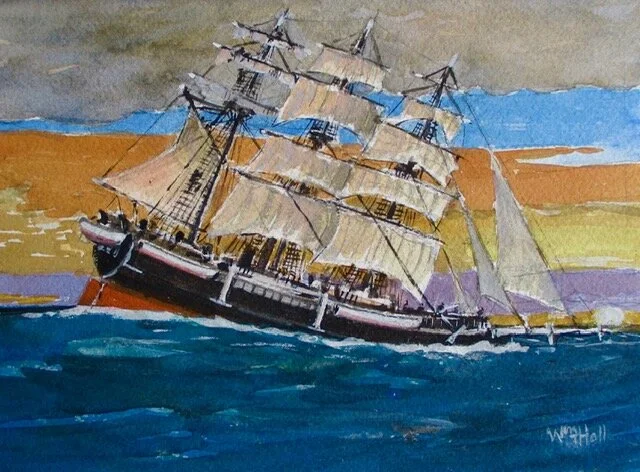

William T. Hall: An island’s crucial boat and the widow’s fish

On the beach with a Block Island Double Ender

— Watercolor by William T. Hall

Block Island is a small landmass shaped like a pork chop 16 miles off southern Rhode Island. It’s where my father was born, in 1925. His entire family were fisherfolk. He got his start fishing at age 10.

Historically, the old salts depicted in the marine art and stories of the past were men, but the wives, mothers and daughters of island fishermen were essential to the life of any Block Island family that made its livelihood from the sea.

Of course, as usual, women saw to all the usual unsung details of daily life in the home and spiritual life in the community, but little remembered today is the extent of the decisions made, and physical labor provided by island women, and how important that was to their family’s survival and success.

Long before my father was born, the indigenous tribes and white settlers on the island took to the sea for their livelihood. They first had to overcome the major geological disadvantages of the island. The high bluffs and open ocean exposure on the southeast corner of the island were perilous, and to the north at North Light were the shallows off Sandy Point that still claim lives of surf fishermen today. These were daunting and dangerous obstacles. For many years the shores of Block Island challenged captains with hazardous approaches and no reliable anchorages.

Progress through adversity

Consider the challenge of designing boats to use at Block Island. For many years, the “perfect Block Island boat’’ was dreamed about, prayed about and then modeled out of wood. It occurred to the early settlers that the way to create a seaworthy vessel on a beach had already been invented by the Celts and Vikings . With a foggy notion of history and woodworking skills barely sufficient to fabricate a house, the new islanders patched together their own unique surf-wise boat. The design was not beautiful, but it was practical because it was based on two important borrowed principles from sea-faring people many hundreds of years before.

It should be sturdy, with two sharp ends for launching from beaches and surviving a following sea when landing. It should have a sail arrangement

best described as “simple and flexible.” It allowed for two small sails, which when reefed down, looked like oversized canvas handkerchiefs. These design considerations proved essential to moving the boats around rocks, then from high cresting waves down onto safe sandy beaches.

The most important aspect of this design was that the boats could be launched into the surf and retrieved from the brine by a small group of men and, yes, women, often with the help of oxen, horses, mules and mechanical hauling contraptions called “capstans”.

This homely workboat was a dory called “The Block Island Double Ender”. It could be launched from the beach into the morning surf and then brought back at night through a different tide, to be stored high up in the dunes safe from northerly storms. This kind of boat varied from 22 to over 36 feet long and was weighted by fieldstones for ballast that would be thrown overboard to balance the weight of a daily catch. The boat was destined to become the mainstay workboat for the island from before the American Revolution but eventually, of course, was made obsolete by steam and gasoline engines.

The stories of the colorful fishermen who manned these seaworthy boats earned them a certain notoriety with many world-class sailors. The boats form a deep mythology as colorful as the exploits of the gods on Mt. Olympus. They had names such as Dauntless, Island Bell and Bessie, I, II and III. There were perhaps as many as 50 boats built and launched from coves around the island. One such beach is even named “Dories Cove”.

For over 200 years, they faced Neptune’s furry and a vengeful Old Testament God, as they fished a bountiful sea around Block Island. Then, over just a few decades, the boats melted away. The end of these boats was ignoble. Finally abandoned by the careless hands of progress, their exposed ribs and rigging melted into the island’s underbrush and rose-hip bushes. It was said by a Civil War veteran, “Only those who had witnessed soldiers left unburied after a battle can feel the shame at the sight of this wasteful demise”.

The holiest of testaments paid to Block Island Double Enders was repeated by the captains who had fished in them, “With all that time and everything they went through, only one boat was ever lost to the sea”. Is it true? As an owner of an original reproduction of this wonderful boat I can only say, “It is possible”.

All along, women have played a part in the history of the island, its boats and its success as an island community. In the early history, when a man’s hand heaved at the side rails, or the harnesses of the

oxen, female voices as well as men’s voices were heard shouting as they all pulled in unison with the men. Every able-bodied fisherman, woman, boy and elder was needed to launch and retrieve the boats of the fleet each day.

Women also helped with maintenance, sail repair, outfitting, marshaling supplies, cleaning the catches, gathering and managing bait, all while feeding their families and sharing child-care.

Some women were on the beaches for much of the day waiting for the boats to return. And some women might ride the family mule back to work in their gardens, feed livestock and hang laundry while they kept an eye on the horizon for their family boat to come into sight. Some made stews and chowders and roasted potatoes in the coals of beach fires while they waited. Some cared for the oxen and set wire minnow traps in the salt estuaries. Some dug quahogs for bait from the wet sand on the lower parts of the beaches for the next day’s bottom fishing. \

When the boats were out the women were assisted by old men and school-age boys and girls, before and after school. Young girls helped the working mothers by babysitting the youngest children, tending stew pots, mending nets and making clothing. The women’s contribution would be universally appreciated on Block Island and earn them an equal place in the fabric and soul of the island.

At the time when my father was young many things had changed. Commercial fishing had become totally the purview of men, often symbolized artistically by heroic images of stalwart captains on mammoth commercial fishing boats. By this time, most daughters of fishing families were educated and provided such services on the island as teaching, nursing, real estate, bookkeeping, town business, cab driving and tourism, to mention only a few.

Regardless of these changes, appreciation of women’s role on the island continued. Quiet acknowledgement by giving shares to those who contribute became a tradition in my father’s generation called simply “The Widow’s Fish”.

Although difficult to translate directly, it means always making sure that all the elder and/or widowed women still living on the island would receive fish from every day’s catch. It was standard for every fisherman and farmer on the island to share part with those in need with little fanfare. Sermons in the island’s churches, grace said at daily meals, dedications at public benedictions and remembrances of departed fishing folks were often framed around the notion of “sharing and appreciation,’’ including the crucial role that women played.

I remember this quiet homage paid by my father during our summer vacations, from Vermont, on the island. Although he had migrated off the island to work as a salesman and gentleman farmer, we vacationed on the island, visiting relatives and friends and fishing daily on boats owned by relatives.

One day we had caught more flounder than we could eat, and my father made sure to separate out the catch into portions or “shares”. In that bounty was a special offering, something he called, “The Widow’s Fish”. He always put that portion aside during the filleting. All the harbor’s fishermen had one or two additional people outside their immediate families who were living alone and as Father would say “are living a little closer to the bone than we are”.

In those days, he’d leave the boat and go up the dock to the phone booth by Ernie’s Restaurant. There he’d call a prospective list of names to ask if they could use some flounder, bluefish, fluke, black bass and occasionally

Swordfish. (The last were getting scarce in those days.) I remember the names on his list -- Ida, Annie Pickles, Aunt Annie Anderson, Blanche Hall and Bea Conley. These were elderly ladies whose homes we often visited on the way home with pails of filleted fish.

As I later found out, my father, when he was a teenager, had often crewed as a deck hand or swordfish striker for the husbands of the ladies we visited. All or most of the men were captains who operated fishing boats that Dad had worked on before he went into the Army, in 1944. It wasn’t until later in life I found out there was an added depth to my father’s gratitude.

In those old days these women had found a way to stretch many of their own family meals so that my father, orphaned at age seven, could stay for dinner.

These grateful ladies of the island formed a matriarchal umbrella of love and service to each other and their community. They always remembered my grandmother Suzie Milliken, whom some fondly called “Sister Suzie,” through a custom they referred to as “calling her to the room’’. The expression was used from Victorian times to mean connecting with a departed soul in a séance. As they thanked and hugged my father, they tearfully called him by the boyhood nickname Suzie had given him.

“Billy,’’ they assured him, “Suzie, would be proud of you for remembering to bring us our fair share”.

William T. Hall is a painter, writer and former advertising agency creative director based in Florida and Rhode Island.

Fishermen at the long-gone fish market co-op building at Old Harbor, Block Island, in the ‘40s.

— Photo courtesy of George Mott

‘Two harlots screaming’

For what I ate

I feel bad.

My soul aches,

my heart is sad.

In hindsight I whispered,

“Eat neither now,”

but each one I defiled.

I don’t know how,

but alas I did

break my vow.

One was tender,

not hardly ready,

the other laid firm

like a solemn jetty

to buttress the tempest

and craving that be

in the dark depths

at the bottom of me.

Although young then

I was no stranger to fate

I could have left them alone to wait

for their honey to gather slowly within

to forever be as they had been,

but instead they heckled loudly

for “Original Sin”.

They are gone now,

but no virgins were they!

My vulnerabilities

their vexing inflated

I’m worse for that

which I have wasted.

And yet no better satiation

was felt with others I’ve tasted.

How will I tell

my one True-Blue

who keeps our flower

of love in bloom.

Shall I explain how I saw

splayed open like confections

full with lust for my direction,

two harlots screaming

in torrid syncopation

threatening doom

with my least hesitation.

Worse, they warned –

once my passion was unleashed

they would only accept

something “complete.”

It would not be hailed as “True”

until the final consumption

of not one, but two.

These bewitching dollops

would no longer wait.

They settled together

to enjoy their fate.

I savored them each

completely, and slowly,

my glee was immense, my

behavior unholy.

Yes, these flaws I sadly declare.

We mortals are no match

for Sirens in pairs.

Gods can repeat this rule

due to their station,

“Any goddess can adapt

to fit her vexation”.

So now I suffer

throughout my life

with guilt, misgivings

and marital strife

because I was tempted

away from my sacred oath

by two heavenly crumpets,

— and I ate them.

“Confession of a Serial Eater,’’ by William T. Hall, a New England- and Florida-based painter and writer

Scratch here

In a house under the stars

are you happy where you are

multi-tasking, double checking,

corresponding, genuflecting?

Wouldn’t you rather be

thinking of nothing, but of us

arching up your back to me

responding softly to my touch?

If you agree come to me

navigate by those stars

unplug, sign off, disengage -

please be carful in the car.

I’ll be here in a perfect mood

open, willing, hungry, waiting,

discard your things til not a stitch

then indicate where you itch.

— “Enough With Working Remotely,’’ by William T. Hall, a Rhode Island-Florida-Michigan-based painter, illustrator and writer

William T. Hall: On his island, one last time for my father

While watching the recent movie Midway, about the Battle of Midway and the tragedy of Pearl Harbor, I heard a sad familiar sound that reminded me of my father’s funeral. It was the sharp report of seven rifles being discharged all at once. It is unforgettable.

“BLAM”!

Then a slight pause...

Then again...

“BLAM”!

Then one last time...

“BLAM”!

Must we punctuate tragic moments with such a horrid sound?

The answer is...

Yes we must.

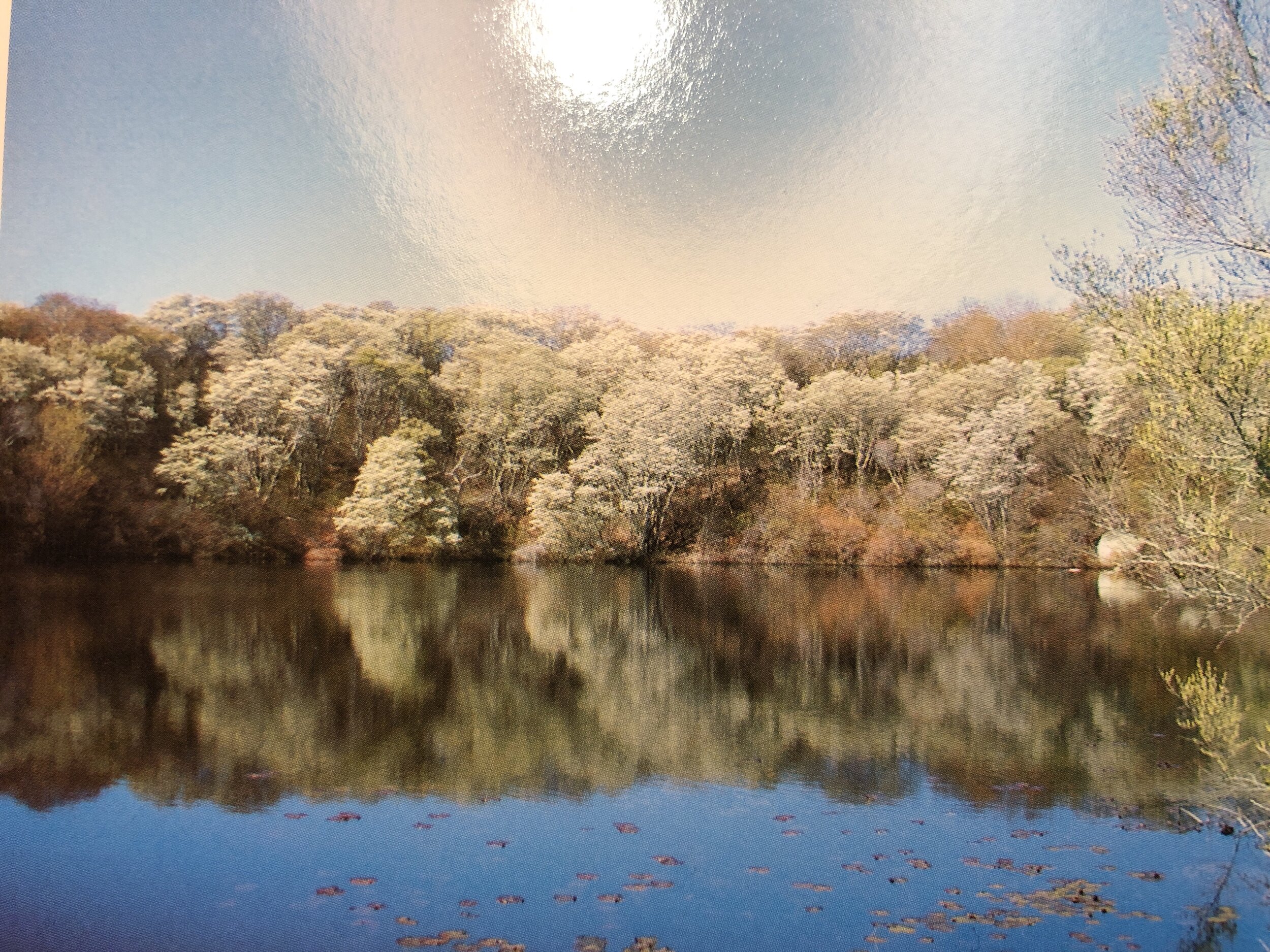

The shad in bloom

— Photo by Kevin Weaver

Preparations for a Memorial

My mother and I carefully picked a day in early May 2000 to inter my father, William Hall, in the cemetery on his ancestral home, Block Island. It was our best guess when the shad tree bloom would be in full array.

Until his last breath, at age 74, he had asserted that he’d not missed being on the island for “The Shad” since World War II.

It’s a spectacle of nature. It’s a moment in a living dream when large parts of the island look like swirls of white butterflies. It creates a cirrus-cloud wisp of magic and myth. Throw in some Hollywood-style ecclesiastical lighting and you’ve got the picture of my father’s romance with “The Shad”.

It was no matter to him that this heavenly show for the rest of the year could be easily described as just woods.

What Everyone Knows

A normal burial on Block Island is handled as a package deal.

The grieving party whose just-deceased relative (or friend) is “from away’’ agrees to a final price covering shipping the loved one in a hearse to the island on the ferry boat. The price includes the homey funeral service at the Harbor Baptist Church, the short procession to the burial site and the post-burial “coffee-klatch” back at the church.

Then after a few hours - and in the middle of hugging relatives and meeting new spouses of forgotten cousins -- starts the panicked reality of the late hour, and the dash to make the last boat back to the mainland. Luckily, the ferry docks are within sight of the church and the captains tend to wait for every last grieving straggler.

To avoid anonymity in death those Block Islanders who have drifted off the island need to be reintroduced to it so that they can be remembered before being forgotten up in the cemetery. Even the descendants of the original English settlers, named prominently on Settlers Rock, have to go through a process of re-emergence during a well-choreographed day-of-burial. It’s like reestablishing their original footprints in the snow after they have long been obliterated by a lifetime of snowstorms. To achieve island quasi-immorality it only takes this one day, with its own special down-homeyness.

Someone Special

So went my father’s last trip back to Block Island, there to be quietly eulogized as one of those island kids who for one reason or another fell into “Off-Islander“ status somewhere along the line.

Human time can be defined in waves. In my father’s case he would be counted among the World War II veterans, Pacific Theater, brand of survivors. At the funeral he would be praised for being a successful businessman, a good husband and a good father, but none of his fishermen relatives or old island cronies would be left to nostalgically tell mourners stories about “that kid” known as a star harpooner of swordfish.

My father had started commercial fishing in 1936, at 10 years old. That’s when he got permission from his father, Allen Hall, to climb the mast and sit on the cross tree of the Edrie L. From that perch, 24 feet above the deck, he was to try his hand at spotting swordfish on his Uncle Charlie’s boat. He excelled because of his excellent eyesight and precise directions given to the helm to find the fish. Soon he was recognized for his accuracy with a harpoon.

By 14 he was the youngest “boy” harpooning swordfish in the fleet and was earning a full share of any fish he spotted or harpooned. This minor local notoriety ended when he was drafted into the Army and shipped out to the Pacific.

That war took many islanders away from Block Island, some to pay the ultimate price of liberty and some to find their way to a more expansive future than could be hoped for on the island, where few returned to live. My father’s war experience did not scar him and he lived a fruitful life, including raising a family and prospering in another part of New England far away from the coast. Although he visited his island family often over the decades his relationship with the place became increasingly remote - and more that of a tourist.

The reality was that the family was thinning out. This hit him hard during the funeral of the oldest Hall elder on the island and it gave him a feeling of a fading heritage. Now more strangers were waiting on the dock meeting the ferry boats when not so long before there had been a receiving line of loving relatives and friends, each shaking his hand, hugging him and calling him by his childhood nickname, “Billy”.\

The island’s identity was shifting. My father was a realist and his life was changing with the times, which he accepted as inevitable. He just didn’t welcome the change with a joyful heart.

This was the man in the shiny hearse rolling off the ferry to return to the island he loved so much. He’d soon be back with his family and relatives for good.

A Good Life

At the funeral service we confirmed through loving remembrances that my father’s life had been by all accounts a good one. The funny tales softened the sorrow.

Everyone at the Harbor Church service agreed that we had all been blessed by his 74 years with us. Meanwhile, as we eulogized him, it became evident that something big was happening outside. There was something at the edge of our senses that suggested that there was a chance that this simple memorial for my father might turn into “A Perfect Block Island Funeral”. It might enter a world where bad was good.]

The first sharp clap of thunder boomed even before we saw the lightning. We realized that what we had sensed had been rolling thunder for some time. The stained-glass windows, organ music, prayers, songs and laughter had masked the storm that was now creeping up on us from the southeast side of the island.

The room was getting darker but it was 11 in the morning. As the wind whipped at a tin gutter somewhere on the roof, the pastor’s wife quietly tiptoed around the room clicking on a few floor lamps and wall lights. People watching her nudged each other quietly. Looking around the room we saw that the local mourners (from the island) were dressed in rain gear. They had rain hats stuffed in their pockets and waterproof footwear ready under their seats; one even had unbuckled galoshes on over his shoes.

In contrast, the mourners “from away” (non-islanders) looked unprepared in their comfortable spring sweaters and dresses. Luckily, they at least had designer-styled trench coats on the hooks in the coatroom. But rain hats, boots and umbrellas for a muddy gravesite ceremony were not evident anywhere in this crowd.

The second thunder clap brought everyone to attention and a slight whimper was heard. Flinching erupted in attendees with over-active startle reflexes. Those who seemed prepared for bad weather were rolling their eyes with wonder as if asking, “Don’t these people from away listen to their local weather reports”?

The weather had changed from undecided to absolutely bad. The modest stained-glass windows rattled with wind gusts and pelting rain. The warm sidelights that the pastor’s wife had switched on were soon augmented with the big overhead lights. Everyone was getting the message that it was going to be stormy at the gravesite.

The Road to Valhalla

No one is more aware of the changes in the island’s social make-up than those who consider themselves “Real Block Islanders”.

“Real” was defined generations ago as “born on Block Island” and of course eventually buried on Block Island. That was the perfect life’s arch of a true islander. Very few can claim that distinction any more.

Evolving medicine and more reliable ferry service have nullified the “island-born” stipulation. In 1926 my father was born in Newport and the next day started his life on Block Island as a “Real Block Islander”. In spite of being hospital-born he met the requirements then needed to be “Real”.

He was born prematurely and had to be kept warm for his first four weeks wrapped in moist towels perched on the edge of an open oven door. My grandmother’s kitchen became Block Island’s first premie ward. My father was attended by every mid-wife and aunt on the island and he soon became everyone’s community property. Thus began his neventful life.

By when I was born, in 1948 ( sadly not on the island), things had changed. It had become a tourist spot. A popular promotional motto was being targeted at people discovering Block Island for the first time. It went like this: “Block Island, come for the day and stay a lifetime.’’ The enthusiasm of first-time visitors on seeing the island’s beauty began to create a new social structure on the island. The newcomers, some of whom became summer residents, brought new ideas, new talents and new personal objectives, but no matter how extraordinary their efforts, they could not line up in that parade of Original, True and Real Islanders. They would never be on that path to immortality and obscurity that leads eventually to Block Island’s cemetery.

In spite of the obstacles to membership in this coveted club of Real Islanders those with the strongest desire for acceptance are still drawn to try to break into the line.

Any deceased islander with an army of mourners headed for the Harbor Church can cause quite a stir, especially when the forecast is for stormy weather and high seas.

When the shiny black hearse carrying my father’s remains crossed the gangplank onto island ground, the island’s grapevine heated up, leading to calls to the church for information.=

Meanwhile, the appearance of a large group of mourners not properly attired for the coming deluge meant that the person about to be buried was probably an “Off Islander,” but scuttlebutt had it that there would also be a rather large island contingent at all or part of the proceedings.

Source Number One

Besides the church, there were other sources of solid information.

Block Island cabdrivers meet every ferry from May 1 to the end of the following November. Only well-established islanders can obtain one of those coveted cab licenses, the possession of which is a channel for a wealth of information about what’s happening on the island. The parking area for the cabs is within plain view of the ferry landing. If you know one of these cabbies you can get first-hand, inside information about what is unfolding at the dock, as well as stuff from any dark corner of the island and the usual sketchy and juicy daily gossip.

I surmise that an inquiry from an island newbie to a cab driver about my father’s hearse might have resulted in a conversation like this:

“Hi, Ed, How you doin?’’

“Good.’

“Hey, who’s that they’re rolling off the boat in the hearse?’’

“Oh Yah, that’s Billy Hall. Yep. He grew to the Sou-East. In the house where Jacobs live now. ‘’

“Lots of well-wishers, eh? I guess he must’a been well known?’’

“Oh, Yah. Billy was a good man. Good family - all fishermen. His mother was a Milliken. Yep, we’re – cousins, I think?’’

“Whad he do for a livin?’’

“Not sure – he moved way af-ta th’war. (pause), but when he was young he could really stick a swordfish. Yessiree. Few better.”

“Oh...?’’ (so on and so on )

And at the Airport

Traditionally, additional information could be obtained at the Block Island Airport lunch counter. It was where the cabbies sipped coffee all day between fares and mingled with passengers waiting for their flights.

On days of big funerals, cabbies, counter girls and mourners from the island and off it exchanged hugs, jokes and news. It was a clearinghouse for information and gossip -- and pie. Everyone seemed related and soon you suddenly felt related to them also.

If newbies liked what they had heard about the deceased in the hub-bub at the lunch counter it would not be unreasonable for them to attend the funeral and go to the gravesite to see whom they might know there. In this way even a newbie might develop a fast, if remote, link with the mourners.

One point was understood. Newbies had to stay for the entire event, no matter how bad the weather. If you invested in saying goodbye to an old Block Islander you were in it for the full course, probably including the coffee-klatch after the burial. This could be important social collateral years later if the deceased name’s came up in conversation. If you had shown up to pay your respects, you could say:

“Yes. I know I was there!”

It was like attending a Viking funeral so you’d know the way to Valhalla.

When Bad Is Good

The wind blew hard and the pouring rain came at the mourners horizontally and from three directions at the gravesite. The lightning, thunder and rain were relentless. The oldest ladies sat in folding chairs under wet tarps and plastic drop cloths with grandchildren squeezed in between them.

Things flew away never to be recovered, but no one left and the ceremony was not rushed. The general mood was sad, but with mourners’ sense of satisfaction that they were joining in a celebration of a life well lived. The hundreds of flags on the veterans’ graves all around snapped in the “Moments of Silence” requested by the pastor.

At the time of my father’s funeral many veterans were being laid to rest every day of the week all over America. Due to the large number of burials, it was nearly impossible to get an honor guard or an official bugler to attend individual funerals. I could not emotionally accept this situation but nor would I complain. My father would not have complained.

On Block Island we have one rule, “We take care of our own”.

Our cemetery is neutral ground, outside of the bounds of daily disputes. This hallowed ground is where we commune with the past and honor individuals whom we respect dearly no matter how long away -- or how recently arrived.

We made an arrangement to honor my father in a way he’d have enjoyed. In a gesture of respect to our family and to the many other veterans whose flags flapped together with his in the wind, a dear family friend and well known federal official provided us with the most memorable final note that my mother and I could have hoped for.

He was to be my father’s one-man honor guard.

Observing the usual safety measures, the honor guard loaded a blank shell into my father’s 12-gauge shotgun, left the mourners at the gravesite and walked slowly and ceremoniously to the top of a small rise.

We could see his hat fluttering and his coat whipping in the wind. His silhouette against the dark sky evoked heroism and the shad bloom around us. As he mounted the shotgun’s stock firmly to his shoulder we could see that his shooting glasses were being pelted by the rain. Time stood still for just a moment. We waited for the sound that gun would make -- one last time.

Blam!

The wind and the rain muffled the report.

White smoke hung in the air above the shooter, and then disappeared downwind into the white cloud of shad trees in the distance=

At my side my mother, inside father’s old raincoat, whispered:

“Perfect.”

William T. Hall is a painter, illustrator and writer based in New England, Florida and Michigan.

Wanderer for whales

“Wanderer,’’ probably rounding Cape Horn, coming from or going to whaling in the Pacific. Watercolor and gouache by William Hall.

Wanderer, last of New Bedford’s once glorious fleet of square-rigged whaling vessels, was built in a Mattapoisett shipyard and launched in 1878. It came to a sad end in 1924, when it grounded off Cuttyhunk in a storm.

Revolutionary privatization

Two American privateers meeting off Newport (Brenton Point off the left) during the Revolution. They, of course, preyed on British ships.

— Watercolor by William T. Hall

Nautical life on Block Island

From William T. Hall’s new exhibit of watercolors, “Block Island Nautical Life and Historical Views,” depicting earlier times of boating and fishing on Block Island. The show runs through Aug. 2 at the Jessie Edwards Studio, on Block Island.

In the show, the gallery says, you can see Mr. Hall’s "use of classical watercolor techniques, his knowledge of boats and Island history, and his talent for story telling {combining} to make this exhibit both a meticulous rendering of old working boats and a narrative of the quotidian concerns of Island mariners. We see the images, and we can read Hall’s brief accompanying stories that draw us into an earlier time on Block Island. ''