WPA art

"Skyscrapers” (circa 1937) (oil on canvas), by Joseph Stella (1877-1946), in the WPA Collection, at the T.W. Wood Gallery, Montpelier, Vt.

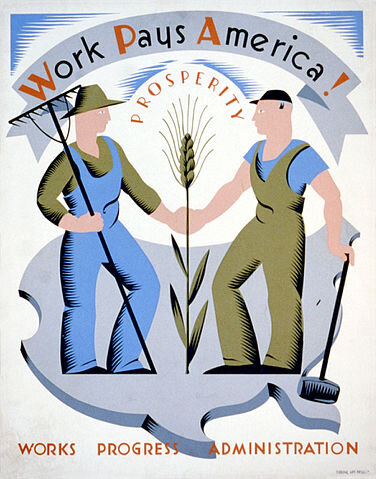

The Federal Art Project (1935-1943) was a New Deal program to fund America’s arts projects under the Works Progress Administration (WPA). It sustained some 10,000 artists during the Great Depression.

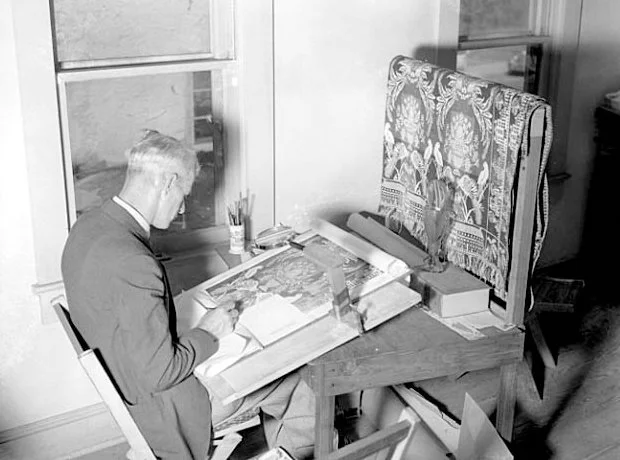

In 1940, Magnus Fossum, a WPA artist, copying the 1770 coverlet "Boston Town Pattern" for the WPA’s Index of American Design.

WPA Pump Station, in Scituate, Mass., built in 1938

A WPA for transportation?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Traffic is starting to back up again in southern New England roads as the economy opens up in fits and starts. I found it bumper to bumper for a while the other week on Route 128 west of Boston. The roads are crumbling and the environmental effects of our extreme car-dependence are obvious. We need to expand mass transit. Yes, fear of COVID-19 has taken a toll on transit ridership but the frustrations and dangers of car travel (far more dangerous than travel on trains and buses) will soon enough send many people back to the likes of the MBTA.

Meanwhile, gasoline prices are very low and will likely continue so for some time to come. So when this depression ends, gasoline taxes should be raised to make the long-delayed improvements in transportation that will be good for the environment and for the economy. Maybe some people left permanently jobless by the pandemic depression can be employed in (Great Depression-era) WPA-style work to help fix the region’s worst transportation problems.

A WPA road project, in the Great Depression

Start rebuilding; battling bike bathos

WPA road project in the ‘30s

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The upside of disaster. The COVID-19-caused lack of traffic has let road and utility work, such as replacing century-old gas lines in Providence’s Federal Hill neighborhood, be done much faster than anyone could have anticipated a few months ago. Which is a reminder that fixing America’s decrepit infrastructure in a sort of WPA-style program would not only employ some of the people who have lost their jobs in our open-ended economic crisis; it would also make us more competitive over the long haul.

Bucking the Bike Bathos Redux

How to bring back rental-bike-and-scooter companies to Providence, firms that have left because of thefts and vandalism?

For one thing, JUMP, Lime and other “micro-mobility” companies must do what they failed to do before – properly staff their services for oversight, which they have tried to do on the cheap. For another, all these vehicles should be locked in racks between use, and in very open and visible places, so that the police are more likely to monitor them. And surveillance cameras should be installed wherever possible. And as I’ve written before, there should be more serious punishments for stealing and vandalizing these vehicles.

Finally, enforce the traffic laws for bike and scooter users for a change!! Stop riders from going the wrong way on one-way streets, running stop signs and red lights, and keep them in their lanes. Will it take a couple of these wild riders getting slammed by a car or truck, and maybe killed, to get the city’s attention and start enforcing the law?

xxx

Meanwhile, Providence, like many other towns and cities, has closed off blocks of streets to most vehicular traffic in response to the pandemic, turning them into walkways, which I guess many people like, especially now that warm weather is here and after months of COVID claustrophobia. But how is it working out for deliveries, especially now that Amazon is everywhere? How do people living along these closed-off streets (though they can come and go) like it? And will these closures cause traffic jams as more people start driving around on our mostly narrow streets as the pandemic controls are gradually lifted?

Llewellyn King: To revive America, fix the gig economy and bring back the WPA

McCoy Stadium, in Pawtucket, R.I., was a WPA project….

…and so was this field House and pump station in Scituate, Mass.

The assumption is that we’ll return to work when COVID-19 is contained, or we have adequate vaccines to deal with it.

That assumption is wrong. For many millions, maybe tens of millions, there will be no work to return to.

At root is a belief that the United States -- and much of the world -- will spring back as it did after the 2008 recession: battered but intact.

Fact is, we won’t. Many of today’s jobs won’t exist anymore. Many small businesses will simply, as the old phrase says, go to the wall. And large ones will be forced to downsize, abandoning marginal endeavors.

When we think of small businesses, we think of franchised shops or restaurants and manufacturers that sell through giants like Amazon and Walmart. But the shrinkage certainly goes further and deeper.

Retailing across the board is in trouble, from the big-box chains to the mom-and-pop clothing stores. The big retailers were reeling well before the coronavirus crisis. Neiman Marcus, an iconic luxury retailer, has filed for bankruptcy. All are hurt, some so much so – especially malls -- that they may be looking to a bleak future.

The supply chain will drive some companies out of business. Small manufacturers may find that their raw material suppliers are no longer there or that the supply chain has collapsed – for example, the clothing manufacturer who can’t get cloth from Italy, dye from Japan or fastenings from China. Over the years, supply chains have become notoriously tight as efficiency has become a business byword.

Some will adapt, some won’t be able to do so. A record 26.5 million Americans have sought unemployment benefits over the past five weeks. Official unemployment numbers have always been on the low side as there’s no way of counting those who’ve given up, those who work in the gray economy, and those who for other reasons, like fear of officialdom or lack of computer skills, haven’t applied for unemployment benefits.

To deal with this situation the government will have to be nimble and imaginative. The idea that the economy will bounce back in a classic V-shape is likely to prove illusory.

The natural response will be for more government handouts. But that won’t solve the systemic problem and will introduce a problem of its own: The dole will build up dependence.

I see two solutions, both of which will require political imagination and fortitude. First, boost the gig economy (contract and casual work) and provide gig workers with the basic structure that formal workers enjoy: Social Security, collective health insurance, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation. The gig worker, whether cutting lawns, creating Web sites, or driving for a ride-sharing company, should be brought into the established employment fold; they’re employed but differently.

Second, a new Works Progress Administration (WPA) should be created using government and private funding and concentrating on the infrastructure. The WPA, created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, ended up employing 8.5 million Americans, out of a total population of 127.3 million, in projects ranging from mural painting to bridge building. Its impact for good was enormous. It fed the hungry with dignity, not the soup kitchen and bread line, and gave America a gift that has kept on giving to this day.

Jarrod Hazelton, a Rhode Island-based economist who’s researched the WPA, says the agency gave us 280,000 miles of repaired roads, almost 30,000 new and repaired bridges, 600 new airports, thousands of new schools, innumerable arts programs, and 24 million planted trees. It also enabled workers to acquire skills and escape the dead-end jobs they’d lost. It was one of the most successful public-private programs in all of history.

As the sea levels rise and the climate deteriorates, we’ll need a WPA, tied in with the Army Corps of Engineers, to help the nation flourish in the decades of challenge ahead. The original was created by FDR with a simple executive order.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

John O. Harney: 'Emergency remote'; a WPA for humanists?; defense workers kept on job

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org):

A few items from the quarantine …

Wisdom from Zoom. COVID-19 has been a boon for Zoom and Slack (for people panicked by too many and too-slow emails). Last week, I zoomed into the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) Leadership Series conversation with Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU) President Paul LeBlanc and HGSE Dean Bridget Long. LeBlanc notes that the online programs adopted by colleges and universities everywhere in the age of COVID-19 are very different from SNHU’s renowned online platform. Unlike SNHU, most institutions have launched “emergency remote” work to help students stay on track. Despite worries in some quarters about academic quality, LeBlanc says the quick transition online is not about relaxing standards, but ratcheting up care and compassion for suddenly dislocated students. The visionary president notes that just as telemedicine is boosting access to healthcare during the pandemic, online learning could boost access to education.

Among other observations, LeBlanc explains that “time” is the enemy for traditional students who have to pause classes when, for example, their child gets sick. If they are students in a well-designed online program, they can avoid delays in their education despite personal disruptions. He also believes students will want to come rushing back to campuses after COVID-19 dissipates, but with the recession, he wonders if they’ll be able to afford it. Oh and, by the way, LeBlanc ventures that it’s unlikely campuses will open in the fall without a lot more coronavirus testing.

Summer learning loss becomes COVID learning loss. That’s the concern of people like Chris Minnich, CEO of the nonprofit assessment and research organization NWEA, founded in Oregon as the Northwest Evaluation Association. The group predicts that when students finally head back to school next fall (presumably), they are likely to retain about 70% of this year’s gains in reading, compared with a typical school year, and less than 50% in math. The concern over achievement milestones reminds me of the fretting over SATs and ACTs as well as high-stakes high school tests, being postponed. Merrie Najimy, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, notes that the pause “provides all of us with an opportunity to rethink the testing requirements.”

Another WPA for Humanists? Modern Language Association Executive Director Paula M. Krebs recently reminded readers that during the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration, though commonly associated with building roads and bridges, also employed writers, researchers, historians, artists, musicians, actors and other cultural figures. Given COVID-19, “this moment calls for a new WPA that employs those with humanities expertise in partnership with scientists, health-care practitioners, social scientists, and business, to help shape the public understanding of the changes our collective culture is undergoing,” writes Krebs.

Research could help right now. News of the University of New Hampshire garnering $6 million from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to build and test an instrument to monitor space weather reminded me of when research prowess was recognized as a salient feature of New England’s higher education leadership. That was mostly before jabs like the “wastebook” from then-U.S. Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) ridiculed any spending on research that didn’t translate directly to commercial use. But R&D work can go from suspect to practical very quickly. For example, consider research at the University of Maine’s Lobster Institute trying to see if an extract from lobsters might work to treat COVID-19. Or consider that 15 years ago, the Summer 2004 edition of Connection (now NEJHE) ran a short piece on an unpopular research lab being built by Boston University and the federal government in Boston’s densely settled South End to study dangerous germs like Ebola. The region was also a pioneer in community relations, and the neighborhood was tense about the dangers in its midst to say the least. But today, that lab’s role in the search for a coronavirus vaccine is much less controversial.

Advice for grads in a difficult year. This journal is inviting economists and other experts on “employability” to weigh in on how COVID-19 will affect 2020’s college grads in New England. What does it mean for the college-educated labor market that has been another New England economic advantage historically?

Bath Iron Works will keep its employees at work.

Defense rests? One New England industry that is not shutting down due to COVID-19 is the defense industry. In Maine, General Dynamics Bath Iron Works ordered face masks for employees and expanded its sick time policy, but union leaders say the company isn’t doing enough to address coronavirus. More than 70 Maine lawmakers recently asked the company to consider closing temporarily to protect workers from the spread of the virus. But the Defense Department would have to instruct the shipyard to close, and Pentagon officials say it is a “Critical Infrastructure Industry.” About 17,000 people who work at the General Dynamics Electric Boat’s shipyards in Quonset Point, R.I., and Groton, Conn., are in the same boat, so to speak. They too have been told to keep reporting to work. In New London, a letter in The Day pleaded with Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont to shut down Electric Boat. Critical Infrastructure Industry. If only attack subs on schedule could help beat an “invisible enemy.”

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Below, “Wong’s Pot with Old Flowers,” by Montserrat College Prof. Timothy Harney.

Time for another WPA?

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

The Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps did some great public projects in the Great Depression – the former building roads, bridges, walls, public buildings and other infrastructure (some of which is still with us), the latter reforesting wide areas, improving parks, addressing erosion on farms and building roads into remote areas. They were both job programs meant to address the immediate unemployment crisis but their work made lasting improvements.

Now, although the jobless rate is very low, some leading Democrats want to create a federal “jobs guarantee’’ to prevent mass unemployment in future recessions/depressions. The basic idea is to hire any American who wants a job and pay him/her $15 an hour and provide health insurance.

Of course, this would be hugely expensive, maybe over $500 billion a year, but backers say raising taxes on the rich, and savings in unemployment-benefit programs, Medicaid and other social services, would make it fiscally plausible. I doubt it: The costs would probably quickly spiral out of control, and it would be an administrative nightmare.\

Could the Feds really put all of the millions of people who would sign up into productive work? Of course, they’d be some jobs requiring little skill, such as ditch digging, picking up litter, some kinds of exterior painting and planting trees, but WPA-type projects now require a lot of people trained in operating complex machinery and even computers. The private sector wants people with those skills and generally pays more than $15 an hour for them.

As the usually very interesting conservative writer Megan McArdle noted in The Washington Post, the massive program envisioned by some Democrats would involve a lot of “make-work.’’ (See:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/bernie-sanders-wants-you-to-have-a-good-job-but-theres-a-catch/2018/04/24/b67a7a56-47ef-11e8-9072-f6d4bc32f223_story.html?utm_term=.a2a2c9a3dc97

But we would benefit greatly from targeted federal jobs programs that put people to work rebuilding our crumbling infrastructure and in such sectors as public health and education.

Oh, by the way, whatever happened to the huge infrastructure program promised by Trump?

'A ghost of a town'

Sheldon Homestead, Deerfield, Mass. circa 1912.

"If it is no exaggeration to say that Deerfield {Mass.} is not so much a town as the ghost of a town, its dimness transparent, its quiet almost a cessation, it is essential to add that it is probably quite the most beautiful ghost of its kind, and with the deepest poetic and historic significance to be found in America....It is, and will probably always remain, the perfect and beautiful statement of the tragic and creative moment when one civilization {Native American} is destroyed by another (white colonists}.''

-- WPA Guide to Massachusetts (1937)

Robert Whitcomb: Too much wind for too much wood on Sept. 21, 1938

“The roaring wind toppled forests in every New England state, with New Hampshire and Massachusetts (east of the eye of the storm) hit particularly hard. The path of destruction spanned ninety miles across....’’ And “70 percent or more of the toppled timber was Pinus strobus – eastern white pine’’ – the most valuable (and vulnerable) tree crop in New England because of its height, straightness and its many uses, from lumber to make houses, to furniture to cheap shipping boxe

(Original review published by The Weekly Standard)

When I was a boy living in coastal Massachusetts I frequently heard stories about the great hurricane that crashed into Long Island and New England on Sept. 21, 1938. Most of the people who described it to me – my father and some of his friends -- were only in their thirties and early forties when they told me about it, and had very vivid stories, especially after a few drinks."

What the 1906 earthquake is to San Francisco, the 1871 fire is to Chicago and Hurricane Katrina is to New Orleans, the ’38 Hurricane (aka “The Long Island Express’’) is to New England and Long Island.

Given the scale of the catastrophe in one of the most populous and richest parts of the country, the ’38 Hurricane at first got surprisingly little attention from the rest of the country because attention was riveted on the Munich Crisis; many assumed that war was about to break out in Europe; of course, that wouldn’t be for another year.

The storm killed around 700 people and destroyed many buildings, bridges and miles of road. Its tidal surge altered long stretches of the southern New England and Long Island coasts.

Stephen Long clearly and dramatically, and sometimes with droll humor, details the mayhem produced by torrential rain followed by winds that gusted to nearly 200 miles an hour on Blue Hill, south of Boston. He serves up a mix of regional history, meteorology, botany, ecology, politics, economics -- allseasoned with anecdotes.

But his book is mostly about the trees that the storm took down, especially in New England’s large and well-established second-growth forests and “the pastoral combination of farm field and forest {that} adorned’’ the region, interspersed by villages with steepled white churches. That’s the (unrepresentative) scene that many tourists most associate with the region. The storm’s massive blowdowns (including of steeples) altered the views in many places.

As a boy, I saw evidence of this damage in the woods next to our house, where there were numerous pits where the roots of uprooted trees had been. From the pits’ shape you could tell which direction the strongest wind came – southeast, at more than 100 miles an hour. And there were still many gaps in the woods where tall trees had once stood.

Mr. Long, founder and former editor of Northern Woodlands magazine, focuses on the ecological, economic and sociological effects of the storm’s destruction of mature trees in a wide swath of New England.

“The roaring wind toppled forests in every New England state, with New Hampshire and Massachusetts (east of the eye of the storm) hit particularly hard. The path of destruction spanned ninety miles across....’’ And “70 percent or more of the toppled timber was Pinus strobus – eastern white pine’’ – the most valuable (and vulnerable) tree crop in New England because of its height, straightness and its many uses, from lumber to make houses, to furniture to cheap shipping boxes. (Mr. Long describes how mighty New England’s cheap-pine-box industry was before heavy-duty cardboard and plastic took its place.)

All this devastated many landowners, already brought low by the Great Depression, who depended on pine sales from their wood lots to make ends meet.

Also torn up were many maple-tree stands, the sap from which provided a lot of extra income to New England farmers and other landowners.

Mr. Long writes very accessibly about why certain trees sustained far more damage than others -- e.g., “The taller the tree the longer the lever and the greater the force it can exert on the ground where it’s anchored.’’ Trees on southeast-facing slopes were particularly vulnerable.

Enter the New Deal, in an example of what perhaps only government can do: Clean up damage from natural disasters that extends over many square miles. Much praise was due the U.S. Forest Service, as well as Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, in responding to a disaster as huge as the ’38 Hurricane.

The first imperative, state and federal officials and an anxious public thought, was to reduce the chances of massive forest fires from the downed and thus drying trees and branches. Indeed, some of the forests were closed to the public for long stretches after the hurricane for fear of fire. That the hurricane had made many of the fire-watch towers inaccessible -- roads were blocked by fallen trees – made it that much scarier.

And so, Mr. Long explains, federal officials, led by the U.S. Forest Service, pulled together the resources of various organizations but especially thousands of otherwise unemployed men working for the CCC (young men) and the WPA (which had older men too). They opened roads and helped clean out much of the combustible debris left on the ground by the hurricane.

The Roosevelt administration pushed the project. Mr. Long describes “the WPA’s own portrayal of its hurricane relief efforts, as seen in an eleven-minute film….Shock Troops of Disaster bears a striking resemblance to wartime newsreels, depicting feverish activity accompanied by charged music and stentorian narration. Referring to the WPA, the narrator described it in this way: ‘Manpower, turning from regular public improvements and services into the breach in times of dire need.’’’

But what to do with the fallen timber taken out of the woods, which could flood the market and lower the already low price of the wood? To address this issue, the government invaded the private market with a vengeance.

Mr. Long explains: “The Forest Service saw the need for a stabilizing influence on the price of logs and the flow of lumber to the market….{so it} put the power of the federal government to work’’ by establishing “a fair price for logs,’’ and buying up all it could and then gradually selling it as “demand required. At the heart of this reasoning was that the purchasing program would allow thousands of local landowners to realize a decent return from what could have been a nearly total economic loss.’’

“The total cost of the salvage program was $16,269,000’’ {in dollars of the time}, of which 92 percent was recovered by the government. It seems doubtful that such market intervention will happen after the next big hurricane blows through. But then, FDR & Co. saw the hurricane response as another way of fighting the Depression.

The cleanup showed just how good Americans, via a collaboration of the private and public sectors, can be at addressing an emergency – as they were soon to prove after Pearl Harbor. And a lot of that hurricane wood was used in war-related products and then in the post-war building boom.

Meanwhile, with the continuing disappearance of farmland, New England is now more forested than at any time in 200 years. Some year, the Northeast will again have a record surplus of lumber on the ground after another huge hurricane. We may then long for a CCC and a WPA.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is overseer of newenglanddiary.com.