David Warsh: In Ukraine, echoes of Vietnam

— Map by Amitchell125

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The most interesting news around in August was the debut of a major series in The Washington Post about the beginnings of the war in Ukraine. Clearly it is intended to be an entry in next year’s contest for a Pulitzer Prize.

The first installment, “Road to war: U.S. struggled to convince allies, and Zelensky, of risk of invasion,” was a ten-thousand-word blockbuster.

The second, “Russia’s spies misread Ukraine and misled Kremlin as war loomed,” ran another six thousand words.

The third, “Battle for Kyiv: Ukrainian valor, Russian blunders combined to save the capital,” was similarly substantial.

And yesterday, a story appeared, not part of the series, about a disaffected Russian soldier who fled the war, featuring lengthy excerpts from his journal. “‘I will not participate in this madness.’”

Plenty of news, but the most striking aspect of the series is its architecture. The Post so far has mostly omitted the Russian side of the story. This is, to put it mildly, surprising. It is always possible that much more background narrative is yet to come. “Begin toward the end” is a story-telling recipe frequently employed in novels and films, but the ploy is not common in newspaper series. On the other hand, given the customary wind-up of important series in December, it is entirely possible that eight or even ten more installments are on the way.

For simplicity’s sake, the analytic foundations of the Russian version of the story rest mainly on three documents. The first is U.S. Ambassador William Burns’s Feb. 1, 2008 cable from Moscow, “Nyet means Nyet: Russia’s NATO Enlargement Redlines’’. We know about this thanks to Julian Assange and Wikileaks.

Burns reported that RussianForeign Minister Sergey Lavrov and other senior officials had expressed strong opposition to Ukraine’s announced intention to seek NATO membership, stressing that Russia would view further eastward expansion as “a potential military threat.” President George W. Bush ignored Burns’s advice and President Obama pressed ahead, backing a second pro-NATO “Orange Revolution” in 2014 that caused a pro-Putin Ukrainian president to seek safety in Russia., Putin annexed the Crimean peninsula in response.

The second is Putin’s long word essay from August, 2021, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’’. That, Angela Stent and Fiona Hill argue differently in the new issue of Foreign Affairs, may matter much to citizens of NATO nations and, especially, the leadership of Ukraine, but Putin’s argument matters more to most Russians and some Ukrainians.

The third is the little-publicized and scarcely noticed U.S.-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership of November 10, 2021. After that, there could be no reasonable doubt among the well-informed on any side that the invasion would take place.

The real news had to do with maneuvering between the US diplomats and military commanders and Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky that took place on the eve of the war. The U.S. emphasized the near certainty of invasion and sketched three alternative possibilities the Ukrainian might pursue: move his government to western Ukraine, presumably Lvov; to Poland, a member of NATO; or remain in place.

Zelensky chose to remain in Kyiv, while discounting the likelihood of invasion to his fellow citizens, seeking to avoid panic. In an interview with Post reporters, he was candid about his reasoning. A follow-up story, “Zelensky faces outpouring of criticism over failure to warn of war,” described the political turmoil that erupted thereafter in Ukraine. A full transcript of the interview followed four days later.

The subtext so far of The Post’s series reminded me of a little-remembered year or two in the early ‘60’s, before the dramatic escalation of the war in Vietnam took place, an episode usually glossed over, but well documented in Reporting Vietnam, Part One: American Journalism, 1959-1969 (LOA, 1998). The world was more mysterious in those days; there were fewer players on the stage.

Three correspondents for U.S. newspapers stood out for their short-lived enthusiasm for the fight against the Communists: David Halberstam, of The New York Times; Neil Sheehan, of the Associated Press; and Malcolm Browne, of United Press International. Feeding them tips were CIA agent Edward Lansdale, battlefield commander John Paul Vann, and, perhaps, RAND consultant Daniel Ellsberg, then himself a hawk. These three charismatic leaders and others on the outskirts of what was then a U.S. advisory group believed that the war against the insurgents could be won if only it were better fought. As Lansdale put it:

It’s pure hell to be on the sidelines and seeing so conventional and unimaginative an approach being tried. About all I can do is continue putting in my two-bits worth every chance I get to add a bit of spark to the concepts. I’m afraid that these aren’t always welcome.

In South Vietnam, the alliance between Catholics and Buddhist broke down after 1963, and before long the U.S. military took over the war itself. Ten more years and millions of lives were required to lose it to North Vietnam.

No such option exists in Ukraine: Ukrainians must fight the war on their own, however powerful are the weapons they are given. Domestic support for the admirable Zelensky may turn out to to be no more durable over the long haul than consensus among his NATO backers. Putin is a bully, but he seems no less formidable than was Ho Chi Minh. And though Putin is angry, he is not mad.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Bitter times —John Kerry, the Vietnam War, me and The Boston Globe

Logo of the controversial anti-Kerry Vietnam veterans group in the 2004 presidential candidate

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

What does a top newspaper editor owe his publisher? The press critic A. J. Liebling famously wrote: “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one.” Tired of arguing with a friend about the implication of that dictum, I threw up my hands a year ago and walked away. Since then, interest in the question has been rekindled. I decided to re-engage

The particular case that interests me has to do with the role of The New York Times in the 2004 presidential election. It was then that the first collision occurred between mainstream news media and crowdsourcing on the internet: The derisive Swift Boat Veterans for Truth vs. the John Kerry campaign. Did the presidency hang in the balance? There is no way of knowing. George W. Bush received 50.7 percent of the popular vote, against 48.3 percent for Kerry; in the Electoral College, the margin was slightly wider, 286 to 251.

In at least in one respect, crowdsourcing seemed to have won its contest that year. More news about dissension within the Swift Boat ranks appeared first on the Web during the second half of the year, rather than in newspapers. As Jill Abramson notes in Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts (Simon & Schuster, 2019), the newspaper business changed after that.

I followed what happened in 2004 because eight years earlier, I had become involved in what turned out to have been its quarter-final match. In 1996, Kerry, the junior U.S. senator from Massachusetts, was running for re-election to a third term against a popular two-term governor, William Weld. Kerry decisively defeated Weld, sought the Democratic vice-presidential nomination in 2000, then secured the Democratic Party’s nomination in 2004 to run against Bush.

Until 1996, Kerry was known to the national public mainly as a critic of the Vietnam War. The ‘80s, which began with the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan and Ronald Reagan’s election to his first term, had changed attitudes toward America’s experience in Vietnam. Though first elected in 1984 – on, among other things, a promise to stop U.S .atrocities in Nicaragua, – Kerry’s 1996 senatorial campaign was the first one in which he sought to tell the story of his war in Vietnam. He gave highly personal accounts of his service to Charles Sennott, of The Boston Globe, and to James Carroll, of The New Yorker, which appeared a month before the election. In reading them, I was struck by certain inconsistencies in the senator’s accounts – in particular, by the relatively short time he had spent in Vietnam.

I was then a columnist on the business pages of The Globe, writing mostly about economics and its connection to politics, but for a year (1968-69), as a second-class petty officer in the U.S. Navy, I had been a Pacific Stars and Stripes correspondent, based in Saigon, and, for a year after that, a stringer for Newsweek magazine.

After Kerry boasted of his service and disparaged Weld for not having gone to that fight, I wrote a column on Monday for Tuesday, Oct. 22, that was headlined “The war hero.” In the course of my reporting, a member of Kerry’s Swift Boat crew, who had been put in touch with me by the campaign, confided in the course of a long conversation a detail that hadn’t appeared before. A second veteran, a former Swift Boat officer-in-charge, phoned the paper to offer additional details. I requested permission to draft a follow-up column, and received it.

A year ago, I told my story about how that second column came to be written. Below, I put into the record a parallax account of the key events of that week, in the form of a November 1996 letter from former Boston Globe editor Matthew Storin to a strident critic of The Globe’s coverage of Kerry in this instance. I include the letter to which he was responding as well below. They are long and painful to read, and unless you, too, are interested in 2004, you can skip them.

I am writing all of this now for two reasons. I learned last year that having retired from the newspaper business, Marty Baron is writing a book. Collision of Power: Trump, Bezos, and The Washington Post (Flatiron) is said to be about his eight years as executive editor of The Post, beginning just after Amazon founder Jeff Bezos purchased the paper from the Graham family. That makes Baron an expert on the central topic here; all the more so since in 2011, he was considered one of the three likeliest candidates to replace executive editor Bill Keller in the top news job at The Times, according to Jill Abramson, who ultimately got the job. I am eager to see what Baron says about The Globe’s 2004 book about Kerry, so I decided to put on the table the first of the cards that I possessed.

I also want to express the conviction that the resounding success of the tactics Kerry employed in 1996 probably cost him the presidency in 2004. During the week in the fall of ‘96 that we waited for the campaign’s reply to questions raised by “The war hero” column, we accumulated several new bits and pieces of information. Had his staff kept its promises, we would have asked questions about them, but I doubt that I would have written a second column, and certainly not the second column that appeared. Probably we would have waited until after the election, perhaps long after the election, to begin to resolve the questions. Meanwhile, Kerry might have learned how to talk about the issues that would be so starkly raised in 2004.

Instead, a hastily arranged Sunday rally, as Storin’s letter makes clear, was the equivalent of an ambush. Kerry and others, including Adm. Elmo Zumwalt, Commander of Naval Forces in Vietnam when Kerry had been there, assembled from around the country and appeared in the Boston Navy Yard to fiercely denounce the second column, barely 12 hours after it appeared in print. The effects were blistering. With the election 10 days away, The Globe covered the rally and otherwise put the story aside.

I received a copy of Storin’s letter to the critic soon after the election, via interoffice mail. In the five years I remained at The Globe, I was never asked by senior editors about what I had learned. The news business was different in those days. Newspapers were still regnant, but their owners embraced differing principles and possessed different points of view. The Globe had been purchased by New York Times Co., in 1993. Under a standstill agreement, the paper was still managed by the Taylor family in 1996, as it had been for 125 years. Even then, the implications of the sale were beginning to come clear. NYT Co. president Arthur O. Sulzberger, Jr. fired Benjamin Taylor as. Globe publisher in 1999, and replaced Storin with Baron in mid-2001.

Kerry considered questions about his experiences in Vietnam, asked in the rough and tumble of the news cycle, to be illegitimate; I and my editors considered them appropriate in the circumstances. None of us, I think, would have felt any compulsion to publish that second column had the campaign kept its promises. We’ll never know. But in refusing to respond, and attacking instead, Kerry had effectively ruled the questions out of bounds.

Kerry’s success in 1996 may have bred over-confidence going forward. The next eight years produced little news on these matters. The historian Douglas Brinkley wrote his campaign biography, Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War (William Morrow, 2004). By the time it appeared, a whole new wing of the news industry had gained an audience – Rush Limbaugh, the Drudge Report, the Fox News Network, Bill O’Reilly and Andrew Breitbart.

When the same ambush tactics the Kerry campaign employed against The Globe were used against him in May 2004 by the organization calling itself Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, it was too late to disarm. Kerry toughed it out. Bluster and evasion had become a habit.

. ••

“November 6, 1996

“John M. Hurley, Jr., 78 Longfellow Road, Wellesley. MA 02181

““William 0. Taylor, Chairman; Benjamin B. Taylor, President; Matthew V. Storin, Editor: The Boston Globe

Gentlemen: ‘

“What has happened to The Boston Globe? What has happened to the proud, 124-year tradition of impeccable journalistic standards?

“David Warsh has disgraced himself. He has shamed The Boston Globe, he has stained the profession you cherish.

“I am a Vietnam veteran, a 26-year friend of John Kerry, and a 4-decade long fan of the Boston print media. (My father was a Boston news photographer for 43 years – 29 with The Boston Post, 2 freelancing, 12 with the Globe – and he instilled in his children an unyielding admiration for the Boston print media.)

“But in 40-plus years of close observation of Boston newspapers, I have never seen a more despicable, more vicious, more baseless attack than David Warsh’s columns on John Kerry.

“Without any foundation whatsoever, without a single witness contradicting events that took place 27 years ago, without a shred of physical or documentary evidence, Warsh levels the single, most vile hatchet job that I have ever seen.

“Where is Warsh’s evidence to contradict these witnesses, where is the substantiation for his vicious speculation? There is none. Not one word. He speculates about the most heinous war clime imaginable – the commission of murder in order to secure a medal – and offers nothing in support of his speculation. Not a single witness. Not a statement. Not a document. Nothing. It is simply Warsh’s own personal, vicious speculation.

“Even a ‘decorations sergeant,’ if he has an ounce of objectivity, if he has an ounce of integrity, is capable of putting this incident into the context of a firefight: incoming B-40s. enemy fire, from both shorelines, third engagement of the day. stifling heat. deafening noise. screaming, shouting, adrenaline-driven chaos. Sheer mind-numbing chaos. Kerry and his crew were trained to do one thing in order to save their lives: react, react, REACT. Lay down a base of fire, or die. It was that simple. Even a ‘decorations sergeant’ understands that. But if you have no objectivity, if you have no integrity, you don’t put the incident into context. you write of war crimes instead.

“And what of that dead VC? According to Warsh, he was Just a tourist on holiday. ‘The one thing that seemed hard to abide was a grandstander. A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’ SAY … THAT .., AGAIN. ‘A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’

“A VC soldier … in the midst of a firefight … armed with a B-40 rocket … aimed at the crew of a U.S. Navy swift boat – and Warsh sides with the dead VC. An unlucky young man, finished off for the sake of a Silver Star by a grandstander.

“Who does David Warsh think he is? What right does he have to casually, callously, with utter disregard for the facts presented to him destroy a person’s reputation. Their character. their integrity, their honor?

“And you let him do it. Twice.

“Where are your journalistic standards. Where is your outrage. Where is your moral indignation. Where is your decency. Where ls your fairness? Do you really believe that Warsh’s vicious conjecture rises to the level of fair, objective comment? Are Warsh’s columns the stuff of which you want your newspaper judged?

“John Kerry’s honor, his crew’s honor, is intact. What of the Globe’s?

“It is important to point out that Warsh’s reporting is replete with errors. Warsh engages in the vilest character assassination imaginable, and he doesn’t even get basic facts right. In any newsroom I have ever visited ‘getting the story right’ is worn like a badge of honor. Warsh didn’t even try.

“Relying solely on personal conjecture (‘What’s the ugliest possibility? ….’) and vicious innuendo (‘Tom Bellodeau (sic) says he was awarded a Bronze Star … but I have been unable to find a copy of the citation.

“Warsh proceeds to trash the honor of Kerry, his crew, and indeed every veteran who has ever been awarded a medal for bravery.

“There is not one word of substantiation in Warsh’s diatribe. There is no foundation, no witness, no evidence, no document that contradicts what has been said or written about Kerry’s war record. Yet Warsh dangles before the reader the most heinous speculation imaginable: that Kerry murdered a wounded, helpless enemy soldier in order to win a Silver Star for himself. An unspeakable crime, yet Warsh offers nothing to substantiate it. The allegation is solely Warsh’s own vicious, character-assassinating conjecture.

“And you let him publish it. Twice.

“Warsh advances his vicious speculation even though there are rock-solid statements and documents to the contrary, statements and documents that completely contradict his spurious, hate-filled conjecture:

“Belodeau told Warsh: ‘When I hit him, he went down and got up again. When Kerry hit him, he stayed down.’

“Medeiros told the Globe’s Barnicle: ‘I saw a man pop-up in front of us. He had a B-40 rocket launcher, ready to go. He got up and ran for the tree line. I saw Mr. Kerry grab an M-16 and chase the man. Mr. Kerry caught the man in a clearing in front of the tree line and he dispatched the man just as he turned to fire the rocket back at the boat…I haven’t seen or talked with Mr. Kerry since 1969, but I admired him them and I admire him now. He saved our lives.’

“Kerry’s Silver Star citation, awarded for ‘conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action,’ signed by Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, states that the enemy soldier had a B-40 rocket launcher ‘with a round in the chamber.’

“Warsh quoted Kerry (from the Carroll piece): ‘It was either going to be him or it was going to be us. It was that simple. I don’t know why it wasn’t us – I mean to this day. He had a rocket pointed right at our boat.’

“Warsh misspelled Tom Belodeau’s name 13 times.

“Warsh referred to Belodeau as the ‘rear gunner’: Belodeau was the forward gunner.

“Warsh reports that Keny was assigned to a boat ‘whose skipper had been killed’; the skipper was not killed, he was wounded, and is alive today.

“Warsh refers to ‘heavy 50 mm machine guns’: they are .50-caliber machine guns. ‘50 mm machine guns’ are laughable; a reporter with even a cursory attempt at accuracy would have caught the error instantaneously.

“Warsh asks: ‘But were there no eyewitnesses?’ There were at least three: Tom Belodeau, Mike Medeiros. John Kerry. All were quoted in the Globe. But Warsh decided that from a distance of 27 years he knew better than they what happened that day. He ignored what they said, he opted instead to write his own personal, vicious, unsubstantiated conjecture.

“When you engage in character assassination. you have an absolute obligation to ‘get it right.’ Warsh didn’t even try. Why was he in such a hurry to get his hate-filled column into the paper?

“You have always been an aggressive, but responsible newspaper. You have never, until now, stooped this low. So, how did these columns happen? How did they get into your newspaper?

“Your journalistic integrity has been trashed by David Warsh, and the editors that OK’d these columns for publication. These columns were not a close call. These columns were flagrantly out of line. 124 years of journalist integrity has been trashed. It will take you years, if not decades. to recover from the stain of these columns.

“Hang your head in shame, Boston Globe. Hang your head in deep, deep shame.

/s/ John Hurley

“P.S. to Mr. Storin:

“And what of you, Mr. Storin?

“Did Warsh act entirely on his own? Does the Globe’s policy of complete freedom to its columnists mean that no editor even questioned Warsh about the foundation of his columns? Even when Warsh’s columns are totally outside his field of expertise? Did no editor request even minimal substantiation of his vicious speculation: a witness, a document, a statement? Anything at all?

“Does the Globe’s policy of complete freedom to its columnists extend to baseless, personal character assassination? Did you and the editors that work for you fail to see a pattern of vicious, personal attacks by Warsh?

“‘… there is,” Warsh wrote, ‘a good, strong, dispassionate reason to prefer Bill Weld to John Kerry.’ Fair enough. He’s entitled to endorse whomever he wants to. But then the pattern of attacks began:

“Warsh, Oct. 15, 1996: ‘he was acquired by John Heinz’s widow in a tax-exempt position-for dollars swap.’

“Warsh, Oct. 22, 1996: ‘The one thing that seemed hard to abide was a grandstander. A Silver Star for finishing off an unlucky young man?’

“Warsh, Oct. 27, 1996: ‘What’s the ugliest possibility? That behind the hootch, Kerry administered a coup de grace to the Vietnamese soldier – a practice not uncommon in those days but a war crime nevertheless, and hardly the basis for a Silver Star.’

“A recurring pattern of vicious, unsubstantiated personal attacks. Is this what constitutes fair and objective comment under the Globe’s current journalistic standards?

“The very day Mike Medeiros was quoted in the Globe saying Kerry ‘saved our lives,’ you gave Warsh additional space, and let him – without a single witness, without a single document, without a single supporting statement – viciously speculate about a war crime, for the very act that Medeiros said saved their lives. A war crime? Admiral Zumwalt, the highest ranking Naval officer in Vietnam, stated that John Kerry’s heroism that day was worthy of the Navy Cross, the second highest medal for bravery that our country awards. (But Zumwalt recommended a Silver Star instead, because he wanted to expedite the awards ceremony and boost the morale of his troops who were taking heavy casualties at the time).

“Every witness that has spoken, every document that exists. every shred of evidence that has been found states that Kerry acted selflessly, with extraordinary heroism. Yet Warsh, without foundation, without any substantiation whatsoever, conjectures about a war crime. And you print it. Is that the journalistic standard by which you want your reading public, your fellow journalists across the country, your publishers, to judge you and The Boston Globe?

“To top off this lame, pathetic performance by you and your editors, you go on television and dismiss Warsh’s columns, saying, ‘I thought in the long run it might be favorable for Kerry.’

“Vicious, unfounded character assassination ‘might be favorable’? Ludicrous, laughable, stupid, sick.

“The basic test of character, Mr. Storin – for a man or a newspaper – is to be able to say, in the face of adversity, ‘We were wrong, extremely wrong.’ “You, The Boston Globe, and David Warsh have failed that test, egregiously.’’

“November 13, 1996

“Mr. John M. Hurley, Jr., 78 Longfellow Road, Wellesley, MA 02181

“Dear Mr. Hurley:

“Your thoughtful letter was very painful to read. You made some very harsh charges, most of which I feel were not in the same context with the decision that I was faced with in allowing publication of the David Warsh column. Nearly three decades after a signal event in the career of our junior US Senator, I had a column with a seemingly new version of events and no one willing to come forward to explain it, despite our holding the column for three days. In the midst of an election campaign, to kill such a column under those circumstances was something I could not defend.

“Here is the chronology of events that led to my decision:

1. “Warsh says he has turned up this odd statement by Belodeau that does not appear to square with the previous He writes a first version of the column that lands on our desks on Wednesday. Because we are getting closer to the election, we consider publishing it on the following day, rather than waiting until the next of his regular column dates.

2. “I telephoned John Marttila, one of Kerry’s senior advisers, and urge him to have the senator talk to Warsh. I assume the discrepancy can be straightened out. John indicates that it is next to impossible to reach the senator, who is on his way to the debate in Springfield.

3. “I tell my editing colleagues Wednesday night that we must hold the column until we are able to (a.) reach Belodeau for additional clarification and (b.) reach Senator Kerry.

4. “Tom Vallely calls me Thursday morning and discusses the Warsh I tell him what Belodeau has said (or perhaps he already knew), and he says, in pretty much these exact words, “We have no problem with that. We have no problem with that/ and explains that the guy Belodeau hit got back up and appeared still able to fire his weapon. Frankly, I am relieved to hear this because it’s a plausible explanation and we can avoid even addressing the issue anew. Vallely says he will produce “his (Kerry’s) commanding officer. I got the impression that Tom would also help get Belodeau back to Warsh and possibly the senator himself, though on the latter point I may have been mistaken. I think Tom might have said earlier that the senator would not talk to Warsh. I had to leave for a journalism conference on Long Island, but at this point I am confident that the column will not be a problem.

5. “Late Friday, I ask to have the column faxed to me. I am very surprised to learn that neither Belodeau nor Kerry has offered anything to Warsh and that the officer has said he was not an eye witness. The New Yorker quote is also puzzling to me. Yet I feel that Warsh deals with the incident with some caution, offering two possibilities. It’s an effort to examine an important incident in the military career of a major public figure who has chosen for some reason — and that is fully his right — to not answer the columnist’s questions.

“From the remove of hindsight, it is now obvious that Senator Kerry chose prior to publication to use the column (of which through Vallely and others he probably had accurate knowledge) to his own advantage. Not only is that his privilege, but it appears to have been good politics. In any event, it probably would not have been possible to get Admiral. Zumwalt here between early Sunday morning and the late afternoon press conference, so that is my assumption.

“Frankly, the column probably would have disappeared without a trace otherwise. After reading it on Friday, I told our executive editor, Helen Donovan, ‘I think this is worth 1,000 votes for Kerry.’ Given your letter, you are probably incredulous at that, but I felt it humanized the senator in a way that has often not been the case in his career. Of course, I saw the negativity in it, but I thought readers would make their own judgments about the issues – as they do with all our opinion columns.

“As to an apology, I would first like to outline what the paper has done in print. We published the story of the press conference on page one Monday, including Belodeau’s explanation for his remark and his account of the battle as well as the testimony of Medeiros, whom our reporter spoke to by telephone. Obviously this piece was presented more prominently than the original column. We then published an op-ed piece by James Carroll, criticizing us in very harsh terms. It is part of our culture to publish a column such as Carroll’s just as it is to publish a column such as Warsh’s. William Safire writes a half dozen speculative columns a year that are as harsh to Bill Clinton as Warsh’s was to Senator Kerry. When was the last time you saw an op-ed piece in the Times that criticized the Times? Finally, we published a piece by our Ombudsman that, like Carroll, said the column should not have been published.

“I personally may regret that the column ran, but, given the same set of circumstances again, I would not kill the column. I have to make those decisions in the context of columns we have run in the past and might run again in the future. We were in the middle of a tough campaign, Belodeau had made a statement that seemed at odds with anything previously published, and despite waiting three days, no one had come forth on behalf of Senator Kerry to explain it. I agree that it’s a sign of character to admit when you are wrong and, in some ways, that would be easier to explain than what I am trying to say here. I believe David Warsh may address his own personal feelings in a future column and, possibly, in a conversation with Senator Kerry if that is possible.

“It pains me to read that Senator Kerry feels this was a low point in his life. I am certain of one thing: It would have been avoided if he had given a statement to Warsh as we had asked. His failure to respond — even if he wanted to call a press conference in advance — took out of my hand a major argument for changing or killing the column (though I believe Warsh would have treated the subject much differently). Your citation of the Medeiros quote is interesting. The campaign obviously chose to make Medeiros available to another columnist, rather than reply directly to Warsh. That’s another legitimate political decision by the Kerry campaign, but it didn’t help with the decision I had to make on Friday evening (deadlines are earlier for Warsh’s column than for Barnicle’s). I understand that the senator and some of his advisers felt wary of dealing with Warsh, but Tom Vallely and John Marttila knew that I had personally involved myself in the issue and could have phoned me back at any time between Thursday morning and Friday night. Though I was out of town, I was easily reachable.

“I do regret — and they are inexcusable — the relatively minor but not insignificant “inaccuracies in Warsh’s column that you cited.

“In closing, I would like to note that you are a longtime friend of Senator Kerry. I understand you may have even played a role in the campaign’s effort to deal with the Warsh column. I am neither a friend nor supporter of John Kerry nor Bill Weld. I do everything in my power, in terms of social relationships, to put myself in a position to make dispassionate decisions as a journalist. I accept that you are upset with us, but I hope you will sometime reread your letter and recognize that you made some emotional charges that were not justified.

“Sincerely

/s/ Matthew V. Storin’’

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: Still the Free World in a second Cold War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Since it arrived last summer, I have been reading, on and off, mostly in the evenings, The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, by Louis Menand. It is a stupendous work, 18 chapters about criticism and performance, engagingly written and crammed with vivid detail. Most of it was new to me, since, while I am always interested in Thought, I don’t much follow the Arts. The book, in short, is readable, a 740- page article as from a fancy magazine. But then, Menand is a New Yorker staff writer, as well as a professor of English at Harvard University,

It is also a conundrum. The first chapter (“An Empty Sky,” is about George Kennan, a key architect of the policy of containment of the Soviet Union, its title taken from an capsule definition of realism by strategist Hans Morgenthau, in which nations after the war “meet under an empty sky from which the gods have departed”). The last chapter (”This is the End,”) is about America’s war in Vietnam (its title from the Raveonettes’ tribute to The Doors on the death of their vocalist, Jim Morrison).

In between are 16 other essays: on the post-WWII history of leftist politics, literature, jurisprudence, resistance, painting, literature, race and culture, photography, dance, popular music, consumer product design, literary criticism, new journalism and film criticism. My favorite is about how cultural anthropology displaced physical anthropology in the hands of Claude Lévi-Strauss and photographer Edward Steichen, organizer of the Museum of Modern Art’s wildly successful Family of Man exhibition in 1955

A preface begins, “This is a book about a time when the United States was actively engaged with the rest of the world,” meaning the 20 years after the end of the Second World War. Does that mean that Menand thinks the US ceased to be actively engaged with the world after 1965? The answer seems to be yes and no. When its Vietnam War finally ended, in 1975, he writes, “The United States grew wary of foreign commitments, and other countries grew wary of the United States.”

During those 20 years, says Menand, a profound rearrangement of American culture had taken place Before then, widespread skepticism existed among Americans about the place of arts and ideas in national life; respect for their government, its intentions and motives, was strong. After 1965, he finds, those attitudes were reversed. “The U.S. had lost political credibility, but it had moved from the periphery to the center of an increasing international artistic and intellectual life.” The change had come about through a policy of openness and exchange.

Artistic and philosophical choices carried implication for the way one wanted to live one’s life and for the kind of polity in which one wished to live in it. The Cold War changed the atmosphere. It raised the stakes.

Menand is right about the big picture, I think. Inarguably the U.S. grew much more free in those years, even as the governments of Russia and China cracked down on their citizens. Whether or not the lively arts were the engine – as opposed to the GI Bill, civil disobedience, the Pill, Ralph Nader, Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobs, the Stonewall Riots, The Whole Earth Catalog, Milton Friedman – hardly matters.

The Free World’s introduction begins with a photograph: Red Army soldiers hangs a Soviet flag from the roof of the Reichstag, overlooking the ruins of Berlin. The photo was a re-enactment, as had been that of U.S. Marines raising a flag atop Okinawa’s Mount Suribachi that had appeared in newspapers six weeks before.

But there was a difference: the Soviet photo been doctored, a second watch on the wrist of the flag-bearer needled away – unwelcome evidence, perhaps, of prior looting in the otherwise heroic scene. Cover-up was the hallmark of Russian totalitarianism, Menand seems to suggest: what the Cold War was all about.

Fast forward 30 years, to the end of the Vietnam War. The book ends with a striking peroration. Menand writes, “The political capital the nation accumulated by leading the alliance against fascism in the Second World War and helping rebuild Japan and Western Europe [the U.S.] burned through in Southeast.” The Vietnamese Communists who arrived in Saigon as the Americans left “did what totalitarian regimes do: they took over the schools and universities; they shut down the press; they pursued programs of enforced relocation’ they imprisoned, tortured, and execute their former enemies. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City and Ho’s body, like Lenin’s, was installed in a mausoleum for public viewing.”

Ahead lay another flight, this time Vietnamese citizens from their homeland. Menand continues, “Between 1975 and 1995, 839,228 Vietnamese fled the country, many on boats launched into the South China Sea [bound for Hong Kong or the Philippine Islands]. Two hundred thousands of them are estimated to have died [mostly by drowning]. Those people may or may not have known the meaning of the word ‘freedom,’ but they knew the meaning of oppression.” The English writer James Fenton, then working as a news correspondent, stayed behind to witness the aftermath of war. In the last sentence of his book, Menand quotes Fenton’s judgement: “The victory of the Vietnamese a victory for Stalinism.”

What, then, of the nearly years since the fall of Saigon, in 1975? The Chinese turn towards global markets after the death of Mao? The American resurgence as an economic hyperpower beginning in 1980? The collapse of the Soviet Union? NATO’s penning-in of Russia? The World Trade Organizations open-arms to China in 2000? The American invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11? The divisions in U.S. civil society that have increased since?

The Winter Olympics in China underscore that a second Cold War has begun. What might be the consequences of it? How long will it last? How might it end? Who will turn out to be its Harry Truman? It’s George Kennan?

The distinction between a Free World and authoritarian regimes seems to hold up, though no longer do we think of the others as “totalitarian.” Britain’s reputation is diminished. Is the U.S. still leader of the Free World? Has its authority shrunk? I put Menand’s book back on the shelf thinking that it was a valuable contribution to work in progress.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, and proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first ran.

Chris Powell: Lies and betrayal from Vietnam through today; rich school employees

With their 10-part series The Vietnam War just broadcast on PBS, documentary makers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick have done a great service not only to history but also to contemporary public policy.

The documentary emphasizes that the famous Tet offensive of Communist North Vietnam and its guerrillas in South Vietnam, launched in January 1968, was actually a military triumph for the United States and South Vietnam but also a political disaster for them. For it exposed the U.S. government's years of lies that the war was close to won.

Indeed, President Lyndon B. Johnson and his political associates libeled the anti-war movement as disloyal and Communist even as they confessed to each other in private that the war was going poorly and was ill-conceived. So the war was continued for another seven years just to save face.

The series also brilliantly contrasted the astounding courage and heroism of U.S. soldiers with the equally astounding stupidity of the strategy that their generals pursued.

A former soldier summarized that strategy this way: Walk into the jungle and see if you can draw fire. Of course, our soldiers did draw fire, suffered terrible casualties, and then withdrew to remote and poorly defended fire bases without ever holding the territory that they had won with so much blood. The United States dropped more bomb tonnage on the Vietnam War theater than it dropped on Europe during World War II, but that didn't hold territory for long either. That former soldier said he especially resented having to fight to take the same ground multiple times.

Of course, this is pretty much the "strategy" now being used in the 17th year of U.S. military intervention in Afghanistan: Draw fire and then retreat with your casualties.

At least the Trump administration, unlike the Johnson administration, doesn't pretend that the war is going well. But like the Johnson administration, the Trump administration continues the war anyway without any plausible plan for winning it -- and this time the American people and even supposedly humane members of Congress are indifferent to another endless war of attrition in Asia.

So maybe in a decade or so Burns and Novick will be able to make a documentary called The Afghanistan War. They could quote the quatrain from Kipling that belongs at the graves of Johnson and Nixon and will belong at Kissinger's:

And the end of the fight is a tombstone white

With the name of the late deceased,

And the epitaph drear: "A Fool lies here

Who tried to hustle the East."

LUXURIOUS EDUCATION: A community activist in Hartford, Kevin Brookman, notes that the city's school system employs about 70 people with salaries of $100,000 or more, many of them above the governor's salary, $150,000, not counting insurance and retirement benefits. The city's new school superintendent is paid $260,000.

If the Connecticut General Assembly doesn't quickly pass a state budget he likes, the governor, operating the state by executive order, may divert to Hartford and a few other cities all the education money state government has been giving to the rest of the state's municipalities.

What will Hartford do with it all? Create more $100,000-a-year positions? Build another stadium?

If experience is any guide, the city won't improve education with it, since student educational performance is almost entirely a matter of family cohesion, of which Hartford has little.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Hilary Cosell: My father's friendship with Muhammad Ali and their fight for justice

“I’m gonna kill you, nigger-loving Jew bastard.”

The so-called Jew bastard was my late father, the broadcast sports journalist Howard Cosell, and the quote typical of the hate mail that poured into his office from the moment in 1964 that he said, “If your name is Muhammad Ali, I will call you Muhammad Ali.”

Muhammad’s death on June 3 was a bit like my father dying a second time, because as long as Ali was alive, a piece of my father still lived. Together they represented the very best that this country has to offer, and exposed the worst, too.

As the Ali accolades poured in, and his status as a national treasure remained firmly in place, as I watched and listened to the round-the-clock tributes, I thought back to those years between 1964 and 1971, during which Ali was stripped of his title, the years he lost in boxing, and the hatred that engulfed him. I wondered how many people lauding him now even remember those days, or the true reasons why he deserved such praise.

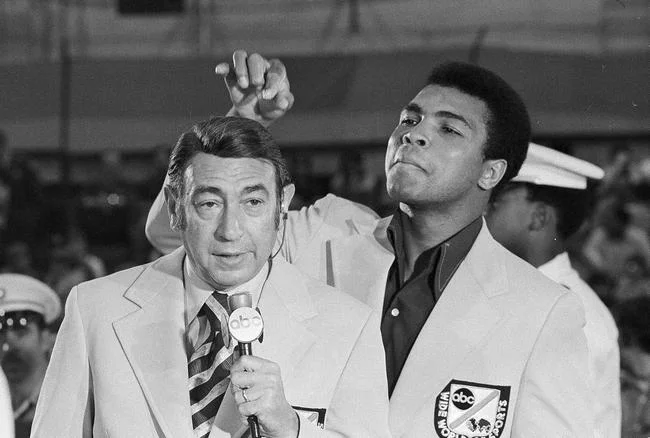

My dad covered boxing for ABC, and so he began to cover Ali. Right from the start they had the kind of rapport that often develops between two smart, fast-talking people. On camera together their relationship was entertaining, and they became synonymous in people’s minds: Ali-Cosell, Cosell-Ali.

But there was a bond between them that had nothing to do with repartee. It was forged during those years of the Freedom Summer, of riots and cities burning in the summer of 1965, the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, the draft, and the Vietnam War, and the Black Power Movement.

My father stood alone and stood his ground when he used Muhammad’s name. Sportswriters and broadcasters refused to speak it, and The New York Times wouldn’t print it. Other boxers continued to use it, and paid for it in the ring.

In 1966 Ali was reclassified as 1A by his draft board, and in 1967 he refused to step forward, and applied for conscientious objector status on religious grounds.

He was stripped of his title, stripped of the right to box professionally, his passport was lifted, and many Americans despised him.

He was called an ingrate, a coward, uppity, someone who didn’t know his place, a traitor, and accused of treason. What made his decision even worse, if possible, was the that he had joined a separatist black Muslim “nation” founded by Malcolm X. (He later left it and practiced a different form of Islam.) It’s no exaggeration to say that he was white America’s nightmare: a young, strong, articulate, separatist black man who said, “No Vietcong ever called me nigger.”

Alone again, my father rose to Ali’s defense. Howard Cosell was a lawyer and knew what was at stake immediately. This had nothing to do with boxing. At issue were freedom of speech, freedom of religion, equal protection and due process.

Amidst the hysteria and hate, my father explained the law, and Ali’s rights, over and over again. Few listened.

When Ali couldn’t box, my dad periodically interviewed him on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, and used him as a commentator on fights. He kept his name, face and case before the public.

One of my favorite stories about them took place at a classic, elegant New York restaurant, called Café des Artistes. It was a hangout for ABC, because the network’s headquarters was directly across the street.

It was a Saturday, lunchtime, and my mother and I got a table and ordered lunch, while my father did an interview with Ali. Suddenly there was a commotion at the entrance and my father strolled in with Ali and his entourage.

“Look who I brought to see you, Em,” he said to my mother, Emmy.

The maître d’ was used to my dad showing up with unexpected people. Tables were quickly pushed together, and Muhammad and friends sat down to eat. I looked around the restaurant, which was fairly crowded with a lily-white clientele who fell silent when Ali arrived, and simply stared. We ignored them.

After they had eaten and left, an older white gentleman cautiously approached our table and asked if he could speak with my father. He nodded.

“Why did you bring him here, Mr. Cosell? He doesn’t belong here. We’re afraid of him. Aren’t you?”

My father looked at the man and quietly replied, “With all due respect, sir, the only thing I’m afraid of are the sentiments you just expressed.” My father then said, “If you’ll excuse me, I’m lunching with my family.” The man scurried away.

Some revisionist historians write that Muhammad and my father were never friends, and that my father hooked on to Ali to further his career, not out of any sense of justice. It’s true that they helped each other’s careers along the way. But Howard Cosell’s defense of Ali defined my father’s career, as well as his character, conscience and courage -- and defined a bond of trust between two unlikely men that would never be broken.

Hilary Cosell is a Connecticut-based writer anda former NBC sports journalist and an occasional contributor to New England Diary.

Lan Anh: Building a foundation for close U.S.-Vietnamese relations

By Lan Anh

On the night of May 22, President Obama landed at Noi Bai International Airport to start his official visit to Vietnam. U.S. Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush had also visited Vietnam while in office.

The American War in Vietnam was a long and sad chapter but that conflict ended 41 years ago.

President Obama’s visit to Vietnam was a dramatic turning point as the two countries establish stronger ties to promote the development, peace and security of the both countries, the Asia/Pacific region and the wider world.

Vietnam has spent much blood, wealth and time defending itself from invadersto regain and preserve its independence. The country has constantly faced threats to its freedom, sovereignty and territorial integrity.

But, overcoming the sorrow of historical events, and some missteps in its economic-development strategy, Vietnam has today achieved remarkable improvements in the economic and other aspects of its development. It has great potential strengths from its location and its population of 100 million, (making Vietnam the 13th most populous nation) including its large number of young people who are very receptive to new technology. It is also playing an increasingly important role in global economic development.

Meanwhile, Vietnam preserves many of its ancient traditions while it stays open to learning and accepting the best aspects of cultures and values all over the world.

Vietnam has become an inspiring story of a country in transition. A nation that suffered the sorrow of a long war with the U.S., Vietnam has since normalized the relationship with America and is taking steps to improve it further. Vietnamese-U.S. relations are now a world-recognized symbol of reconciliation and of progress toward a peaceful, more secure and developed world.

America has the world’s largest economy and is the global military superpower. Thus, the U.S. plays a crucial role in preserving stability around the Earth. American military power can be deployed quickly to any place in the world. Further, America is the innovation hub of the planet. It’s where leading technologies are constantly being invented and refined with great international impact.

Since World War II, the U.S. has led the establishment of a network of multilateral organizations -- most notably the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and such regional security organizations as NATO. In part becase of these organizations, the U.S. has strong allies around the world.

These factors are crucial parts of the foundation for stronger Vietnamese-U.S. relations.

Prof. Thomas Patterson, a leading Harvard scholar on politics, press and public policy, and a co-founder and director of The Boston Global Forum (BostonGlobalForum.org), said that the bases for a strong and sustainable relationship between the U.S. and Vietnam are trust and respect for each other and mutual understanding of each other’s needs and values. Despite some inevitable differences, the two countries have many shared goals, which include building their own and each other’s prosperity, friendly cultural exchanges and peace and security in the South China Sea (called in Vietnam the East Sea). Strong andfriendly U.S.-Vietnamese relations will foster the strong growth of the two countries in the Pacific Era.

The U.S. can help Vietnam with capital and advanced technology so that Vietnam can continue growing its knowledge and innovation economy via such technology solutions as artificial intelligence (AI) and network security.

After the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement (TTP) comes into effect, Vietnam’s GDP is projected to increase to $23.5 billion in 2020 and $33.5 billion in 2025. Its exports are projected to rise by $68 billion by 2026. Under the TPP, big markets, such as the U.S., Japan and Canada, willeliminate tariffs for goods imported from Vietnam, which will obviously give its exporting activity a big boost..

Meanwhile Fulbright University Vietnam has officially been granted approval to open. This is a milestone in the journey of cooperation between U.S. and Vietnam in education. Further, the University of California at Los Angeles ( UCLA ) will soon work with Vietnam to carry out new initiatives in global citizenship education.

To establish itself as a major global player, Vietnam needs to be independent of bigger countries so that it can strategize its path ahead while following universal standards and values. Vietnam will raise its visibility in the world with a loving, tolerant and generous attitude.

Vietnam has overcome sorrow and loss to make peace with other countries that caused it pain. Hence, Vietnam has become a symbol of reconciliation and can play an important role in preserving international peace and security in the Asia/Pacific region and around the world.

For example, Vietnam can contribute to the effort to resolve conflicts between the U.S. and Russia, between Europe and Russia, between China and Russia, between the U.S., Japan and North Korea, and between the U.S. and China. Vietnam could also become a centerfor finding solutions to conflicts in the Middle East and forhelping North Korea integrate with the rest of the world (as when Vietnam helped Myanmar reintegrate). And it can be a pioneer in building harmony and security in online space in South East Asia and around the world. This can include educating people to be responsible online citizens in Internet era; teaching them to respect each other’s culture, knowledge and morality, and promoting initiatives for global citizenship education.

Building strong Vietnamese-U.S. relations, as well as the other initiatives cited above, can’t be completed overnight but the path to a brighter future is opened. Tomorrow has started today.

Lan Anh is a journalist for VietNamNet.

Llewellyn King: Where the motor scooter reigns

HANOI I want tell you about Vietnam: its people, its culture, its economy, its disputes and its aspirations.

But I can’t. Not yet.

Like other visitors to this capital city, I’m not focused on the wide, French-colonial boulevards, the roadsides decorated with extraordinary ceramic mosaics and the great parks; the glorious architecture, which tells its history; traditional, colonial and modern; or the fabulous food, informed by the French but resolutely Vietnamese.

No. I’m totally mesmerized by the traffic: one of the wonders of the world. It’s a wonder not because, like so many of the world’s cities, it’s so terrible, but because it flows in the most extraordinary way. It’s the triumph of a lack of system over a system.

Hanoi has few traffic lights, except on major thoroughfares, and no stop or yield signs. Traffic moves along at about 15-miles-an-hour; sometimes a little faster and sometimes slower, depending on the time of day.

Looking at the traffic is like watching a column of ants, going hither and thither in a courteously chaotic way. The only absolute rule on the roads is to keep to the right. Everything else is improvisation.

At the heart of this traffic miracle, this way of moving millions of people with little delay, is the humble but iconic Vespa scooter, its imitators and relations, all powered with small engines in the 150 cc category. For those not intimate with the intricacies of motorcycles, a top-of-the-line Harley Davidson comes in at 1,247 cc.

But central to the Hanoi traffic triumph are scooters and very light motorcycles (some of them electric), the occasional moped and even bicycles -- although compared to when I was here 20 years ago, the bicycle has nearly disappeared.

To the more than 3 million scooters, most of which take to the streets daily, add the skill, courtesy and physical courage of the riders. They weave, dodge, brake, swerve, swoop, accelerate and slow in what, to American eyes, is an unscripted ballet with a cast of millions. The dance is known, but the choreography is new by the split-second.

There are cars, too, but they’re the minority. They let themselves into the shoals of seething motor scooter riders with a confidence that I'd never have. I’d never go anywhere, being convinced that I’d plow down dozens of intrepid riders with my first tentative yards onto the road. You must not only have patience, but also enough boldness to know that the river of motorcycles -- a river that ebbs and rises, but never ceases -- will accommodate you.

I sit in the back of my taxi convinced that blood will flow as I watch young and old glide by with a determination only otherwise seen in NASCAR drivers. The dance is fast and furious; the music is all New World Symphony.

It is worthy of study by fluid dynamists. Maybe the traffic, the smooth-flowing traffic of Hanoi, should also be studied by sociologists.

Everything happens on the darting, rushing motor scooters and mopeds of Hanoi. Families of three are transported, young men and young women ride abreast and meet on wheels.

If you want to cross the street, pluck up you courage, ask forgiveness from your Creator, and step into the maelstrom of motorized wonder, believing, as you must, that the throng of riders in Hanoi have extrasensory perception and will part, like the Red Sea, for you.

Who would believe that watching traffic could be recreational? Worth the trip, almost.

Reporting on Vietnam, with its intriguing culture, emerging economy, territorial contentions, and future relationship with the United States, will have to wait. There may be a moped in my future.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of “White House Chronicle” on PBS. His e-mail is lking@kingpublishing.com.

Llewellyn King: The rise and fading of 'The New Class'

"The New Class” was a concept in the 1970s that various writers and commentators, led by Irving Kristol, used to describe an important social and political phenomenon of the time. It represented a kind of Fifth Estate, or extra-curricular branch of government. The new class in the context of the time had nothing to do with the use of the same term (sometimes employed to describe the elite of communist-run nations), but had everything to do with what had happened in the turbulent 1960s.

Most especially, it was a manifestation of the opposition to the Vietnam War by young professionals in the United States. By the time Kristol used the phrase, he had already taken his epic journey from the left to the right and was already ensconced as the godfather of neo-conservatism. As I remember, he used his column in The Wall Street Journal to identify the New Class and to attack it. I, too, was writing about it and was leery of its effect on energy supply, but intrigued as to whether a whole new social strata was going to change things; whether we were going to see policy by the young, for the young.

The new class was a rump of disassociated and unaffiliated professionals who had been impacted by the draft and were sensitized to the other social issues of the 1960s – the civil rights, the environmental and the women’s liberation movements. The New Class was important because it was smart and it knew how to use power effectively. It did this by co-opting journalism and using – and perhaps abusing -- the court system.

They were people who had either served in Vietnam or had avoided doing so by fleeing the country, seeking deferments, or, actually rejecting the draft and going to prison. The latter, predictably, produced a surge of interest in prison reform. The draft-avoiders were drawn into the other social issues of the time. Their most profound impact was probably on the environmental movement. To this day, the environmental organizations influence public policy by the use of media and selective litigation -- tactics perfected by the new class.

The New Class was in many ways a non-political movement, leaning to the left but not exclusively. It was the result of comfortable, middle-class kids waking up to what was wrong with the society they lived in. Because they had, in their view, felt the heavy hand of government, they were appalled by conditions in black America, the criminal-justice system and the state of environmental degradation. Of course, they were appalled by the war and the institutions that supported it, including corporations, government, universities and the military. With the end of the war, came the end of the New Class; not immediately, but surprisingly fast.

Its lasting legacy is in tactics, not policy. Its members morphed into a generation of self-interested professionals; its idealism, like the war, a fading memory. As a social pressure group, the New Class has left its mark. It showed how effective a few people with literary and legal skills could redirect policy. As it was not affiliated with a political party, or even a defined philosophy, it could pick its targets. In today’s world of rigid left and right, the power of unaffiliated movements is abridged, if it exists at all. I used the term "New Class'' contemporaneously with Kristol, but I am not sure whether I had just heard it and it had seeped into my consciousness.

At the time, I thought the use of the courts was excessive and I wrote and criticized the new class. But I was fascinated by how they had gotten their hands on the levers of power outside of Congress and the presidency but powerfully affected those institutions. Looking back, one wishes the New Class were still a force: upset about the wanton cruelty of the immigration standoff, angry about income inadequacy, appalled by the surging power that mergers and acquisitions are handing to a small number of supra-national organizations, and worried about unfettered money in politics. Global warming would be a classic issue.

The New Class drew its strength from being indignant but without an organization -- just a few good writers and propagandists here and a few sharp lawyers there. They were amorphous and effective. Would they could be reprised.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of "White House Chronicle, ''on PBS. His e-mail is lking@kingpublishing.com.