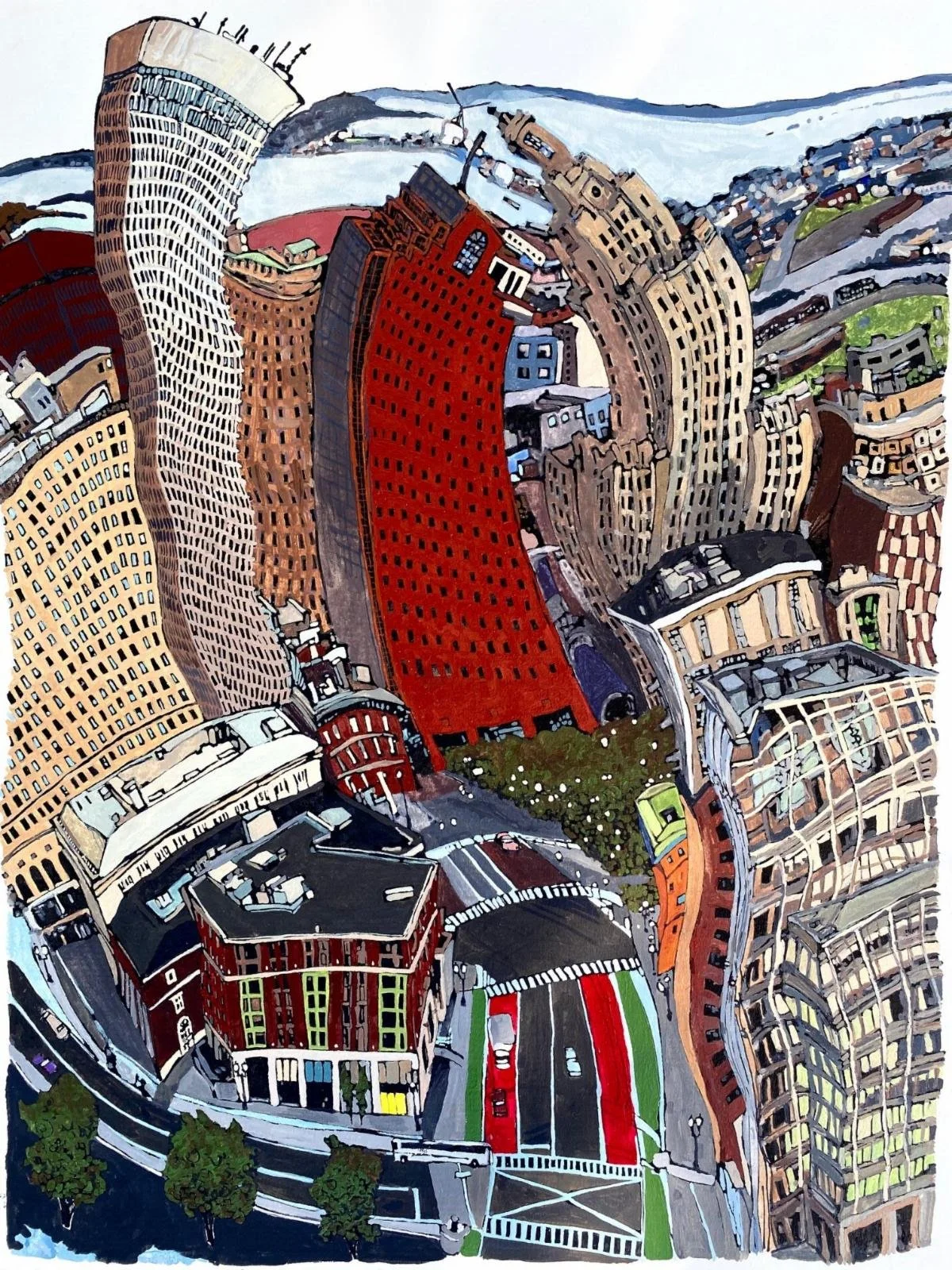

Plastic Providence

This work by Rhode Island artist Jim Bush can be seen at the Providence Art Club March 6-25.

Here’s his description of his background:

“Jim Bush grew up in Cambridge, Mass., and graduated from Kenyon College with a double major in Studio Art and Political Science. He is an award-winning artist, member of the Providence Art Club and a former member of the Sakonnet Artists Cooperative, in Tiverton, R.I. His editorial cartoons appeared in The Providence Journal from 1994-2012. Nationally his cartoons have appeared in the Washington Post National Weekly Edition, The Dallas Morning News and he has drawn for the Tribune Media Services College Press Syndicate.

“In 2007, Jim purchased a building in the historic district of downtown Warren, R.I. and spent a year converting it into an art studio and gallery. Jim focuses now on his fine art painting, primarily acrylic and watercolor. He enjoys painting animals, seascapes, landscapes, farm scenes, architecture -- life around him. His style continues to reflect his cartooning foundation, often displaying his subjects in a light-hearted and off-beat way.’’

Caitlin Faulds: Trying to save a drowning coastal marsh

Wenley Ferguson, of Save the Bay, and many others have spent more than five years trying to save the drowning Sapowet Marsh, in Tiverton. R.I. marsh.

— Photo by Caitlin Faulds/ecoRI News)

Common reed (Phragmites australis) is an invasive species in degraded marshes in the Northeast.

Salt marsh during low tide, mean low tide, high tide and very high tide (spring tide).

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

TIVERTON, R.I.

The grasses are dying. Clusters of broken, denuded stems stand in shallow pools of brackish water, making a patchwork of the low-lying marshlands.

The slow balding is invisible from the blacktop of Seapowet Avenue, hidden behind a thick curtain of phragmites. But standing boot-deep in the peat, surrounded by the sulfuric scent of decomposition, the bare ground is clear evidence of the steady saltwater creep happening in marshes across Rhode Island.

Spartina alterniflora, or smooth cordgrass, is notoriously salt-tolerant and a common feature in saltwater marsh environments.

“They can grow along the edge of the cove and get flooded twice a day, but they can’t grow in standing water,” said Wenley Ferguson, shovel in hand. All around, the sunlight glints off pools of standing water, unable to drain and slowly growing with each high tide.

The average sea level in Rhode Island has increased by about a foot since 1929. Storm surges and king tides have pushed further and further inland. Normally, the marsh would respond to the rising high-water line by matching the migration inland.

But with the sea on one side and a dense web of roads, development, cultivated fields, and invasive species on the other — and accelerated sea-level rise on its way — Sapowet Marsh has nowhere to move.

But Ferguson, the director of habitat restoration at Save The Bay, is working to save the marsh from that saltwater grave.

Ferguson has been working with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) at the Sapowet Marsh Wildlife Management Area, a 260-acre state property, for more than five years now.

The coastal edge of Sapowet has seen more than 90 feet of shoreline erosion in the past 75 years. Under Ferguson’s watch, Sapowet has become home to the largest marsh migration facilitation project in the state — a small counter to the forces at play.

“When I say facilitate marsh migration,” she said, “it’s kind of like prepping the land for the marsh to migrate.”

Back in 2017 and 2018, Save The Bay and DEM, along with the Tiverton Conservation Commission, restored 9 acres of coastal grassland and reestablished beachside dunes on the northern side of the marsh to slow erosion.

Now the work has moved to the west and southeast sides of the marsh — and the strategy has changed to match.

Along the western front

The cordgrass roots are taut, but they cut easy. Just one stomp and the shovel sinks through the muck, water pooling up and over the toes of Ferguson’s black rubber boots.

It was a warm and clear November day — too warm, according to Ferguson. She packed for a cool fall day and wore a blue-flowered fleece, but 60 degrees means she’ll be sweating by midday.

Earlier in the week, Ferguson — along with a handful of DEM employees and volunteers — used shovels and a small excavator to dig a weaving network of runnels through the marsh. These shallow creeks will give the pooling water a route out to Narragansett Bay, allowing the area to slowly drain.

If the root zone of the marsh plants is able to dry even slightly, they will grow “healthy and happy,” Ferguson said. Healthy plants build up a stronger root base, and a stronger root base makes a coastline more resilient to erosion and sea-level rise.

But “we don’t want to drain it too fast,” she said. It has been three days since they dug the first runnels and the water level has dropped only slightly, exposing a few inches of bare mud — exactly as planned.

The standing water is thick with unconsolidated sediments and topped by a bacterial mat. If the water rushes out all at once, this sediment will pour into the bay. It’s better to dig in phases and let it settle out in the marsh, maintaining as much high ground as possible.

They are back on this day to adjust the runnels, excavating the areas where the muck has naturally dammed up. Lucianna Faraone Coccia, a Save The Bay volunteer and an environmental science master’s student at the University of Rhode Island, shovels out a cluster of grass roots.

“If that’s in there, it could plug up this whole runnel,” said Faraone Coccia, glancing down to point out a fiddler crab fumbling its way along the channel with its unbalanced claws.

With each shovel-full, the flow of water grows incrementally stronger and piles of dislodged peat beside the runnels grow larger.

“That’s technically considered fill,” said Ferguson, tossing another glob of peat toward the pile beside her. “We actually leave the peat on the marsh and we create these small little islands.”

These islands are about a chunk of peat thick —some 6-12 inches, not too high, Ferguson said — but that small elevation rise “is like a mountain in a marsh.”

Ferguson fought to keep the peat in the marsh, acquiring additional permits from the Coastal Resources Management Council, DEM’s Office of Water Resources, and the Army Corps of Engineers. This microtopography is essential for a healthy marsh surface, she said.

“These areas will just be a little higher, and they might recolonize,” Ferguson said. “And when I say might — they do recolonize.”

Within one season, the islands will host new sprouts of cordgrass, or they’ll prove high and dry enough to support clusters of high marsh grasses. The clusters of high grass will make ideal nesting habitat for the saltmarsh sparrow.

As healthy salt marsh has waned, so has the population of the saltmarsh sparrow — a bird that makes its nest out of a cup of dense high marsh grasses. The nests are built to withstand the highest moon tides, created with a dome so “the eggs float, but they don’t float out of the nest,” Ferguson said. But the area here is flooding too frequently, contributing to nest failure.

“That’s why these little islands that we’re creating are really valuable habitat,” Ferguson said.

Wenley Ferguson is constantly looking for clues to what shaped the marsh seen today.

Old ways and leftover lines

The state of marshes today are the result of centuries of human development and marshland intervention. According to Ferguson, nearly every marsh in the country holds some sort of historical impact. They are in no way pristine.

“So many of them were manipulated in this area for agricultural activity. And then in more recent years, we put roads along them,” Ferguson said. “We culverted them. We created duck habitat and impounded them. We filled them.”

From the 1700s to the 1900s, about 50 percent of marshes in the region were filled, according to Ferguson. Agricultural embankments have manipulated the marsh surface too, dating back to about the 1600s, when people started haying in these areas.

“The fresher the marsh grasses, the fresher the water table, the greater the value of the hay,” she said.

When she digs these runnels, Ferguson is always scouting for clues to what shaped the marsh seen today. A shovel full of root matter means a stagnant pool was once a field. Water pooling along straight lines could be a sign of an old embankment. Long straight trenches are likely remnants of old mosquito ditches — once made to reduce mosquito breeding grounds but now speeding marshland erosion.

The marsh’s tired past — coupled with its location in an old river valley whose steep sides make marsh migration difficult — spell out a challenging future.

“That’s why what we’re doing today is trying to restore some health of the marsh … under current conditions,” Ferguson said, “but always looking at where the marsh wants to go.”

An excavator heads into a thicket of phragmites growing on the eastern edge of Sapowet Marsh.

The eastern blockade

“Be careful of your eyes walking through this,” said John Veale, habitat biologist with DEM’s Division of Fish and Wildlife, as he pushed away the sharp corners of dozens of broken phragmites. “It can be a little bit dangerous.”

In the past century, invasive phragmites species — few native phragmites remain — have taken advantage of weakened saltwater marsh ecosystems to rampage through North American. The eastern edge of Sapowet Marsh, tucked below Old Main Road and several DEM-owned cornfields, is no different.

In many ways, phragmites are the perfect storm. Their feathery seed heads catch the light beautifully, but they also catch the wind and spread like wildfire. Once the seeds take hold, the reeds grow so densely they all but eliminate animal habitat and outcompete native grasses.

On Sapowet Marsh, it serves as an impenetrable blockade to marsh migration. Only a few grapevines are brave enough to reach their tendrils into the thicket. For the marsh to move away from the encroaching seawater, the phragmites need to loosen their hold. But that’s a notoriously difficult task.

“There’s no way we could do it with a shovel,” Ferguson said. “I mean, it’s just so hard. It’s one thing a little patch of phragmites. It’s another thing when it’s head-high.”

Mowing and burning do little to control phragmites, and pulling them out by the roots quickly proves costly. But like the smooth cordgrass, it is vulnerable to salt water. If Ferguson can drain the pooling fresh water and facilitate tidal flow up into the phragmites, they might dissipate — and the native grasses might have a chance at survival.

“We’re not going to get rid of the phragmites, but we can reduce the height and vigor of the phrag by facilitating that freshwater drainage,” she said.

Ferguson is in the early stages of battle on this front, just figuring out the plan. The phragmites grow 10-12 feet high in places, obscuring the lay of the land.

“There’s enough water,” Ferguson said. “It’s coming from someplace. I just can’t figure out the drainage cause it’s too thick.”

She has called in the help of an excavator. Within a few hours, the machine has established a clearing in the reeds and deepened part of a natural creek. Once some of the standing fresh water drains it will be easier to gauge the direction of the water flow.

Ferguson and her team intend to elongate the creek and the old agricultural ditches — putting past mistakes to better use — but for now the plan is still in development. Better to move slowly than be patching more mistakes up in a hundred years.

“The deterioration along the marsh edge is pretty remarkable, in a terrifying sort of way in my mind,” said Ferguson, pausing to point out a flock of buffleheads skimming into the water. “So that’s why we want to be really cautious on not making new openings for that erosion to expand upon.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

‘Embracing chaos to make art’

“Chaos Gives Birth To Being’’ (oil on canvas), by Daniel Heyman, in his show “Summons,’’ at Cade Tompkins Projects, Providence, Oct. 30-Dec. 31.

Kathleen Tolan in the “Summons’’ catalog essay, writes:

“{T}h giant, squatting on bright green rocks in a blue sea, his body covered with babies crawling on him, being born by him. He points up at a bunch of purple grapes. I think of Dionysus, of the playful lover of life, and I think of the necessity of embracing chaos to make art.’’

The gallery says:

“Daniel Heyman is an artist whose work in drawing, printmaking and painting directs the viewer's attention to contemporary social and political issues. Deeply interested in narrative, he uses images to tell stories that combine a love of history and myth in an effort to provoke discussion and empathy. In his recent “Summons’’ series, Heyman emphatically returns to images without words. His previous effort, the monumental woodcut “Janus’’ from 2019-2020, represents time as an endless string of birth, renewal and death for creatures and ideas. Here, even the very human act of making culture is seen as both creative and destructive, signaling the profound influence Japanese art and culture has had on his work.’’

Daniel Heyman lives in Tiverton, R.I., partly a Providence and Fall River suburb and partly an affluent summer place with a beautiful shoreline and some farms, too.

The Union Public Library, part of the Tiverton Four Corners Historic District, has been operating since 1820.

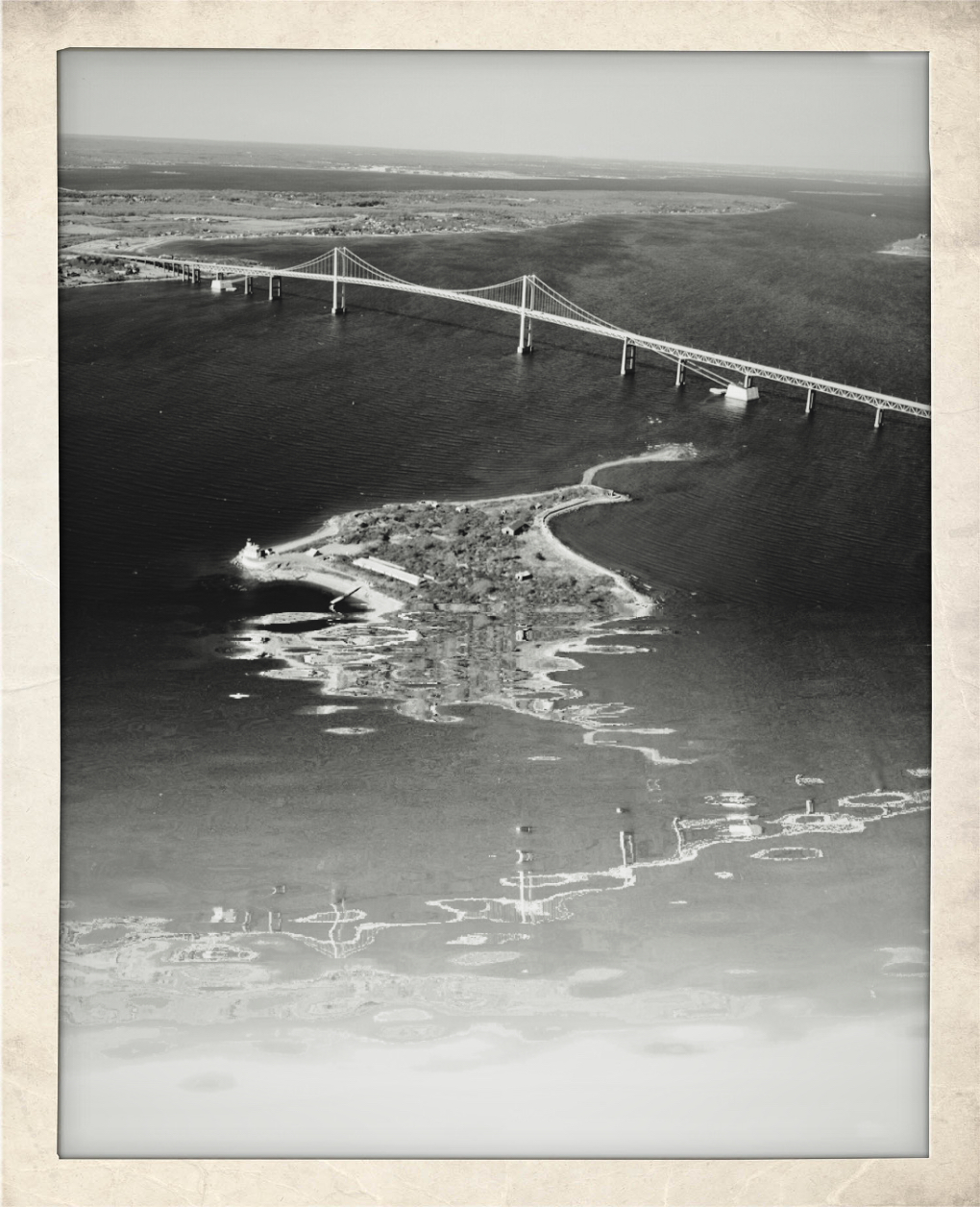

View from Ft. Barton, in Tiverton

Wampanoags' bad gamble

The Old Indian Meeting House, in Mashpee, built in 1684 and the oldest church on Cape Cod as well as the oldest Native American church in the eastern U.S.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The U.S. Interior Department has rescinded the reservation status of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, which has been seeking permission to build a casino on land it owns in Taunton. The Cape Cod-based tribe itself will be allowed to keep federal recognition as a Native American tribe but the federal action presumably kills the plan for a casino.

The casino business is inherently sleazy and casinos (which aren’t open now because of you-know-what) are cannibalizing themselves. Far better to create a highly diversified long-term economic development plan, but gambling revenues continue to look alluring as a quick fix.

The fewer casinos the better. But I still feel sorry for the tribe, especially knowing that their casinos would have competed with Twin River’s two nearby casinos, in Lincoln and Tiverton, R.I. Twin River has close connections with the Trump administration, ruled by a former and failed Atlantic City casino mogul. Surely politics had nothing to do with the decision…..?

Never a shortage of suckers

The idea, of course, in all this is to avoid having to get public revenue honestly by imposing and when necessary raising taxes. It’s far easier to get a slice of a casino’s take, much of which comes from low-and-moderate-income people and much of which goes out of the region to distant owners even as it drains money from local business and increases bankruptcies and crime (especially embezzlement).

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb's Oct. 27 "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com.

And so the casino cannibalization will continue in New England, as Connecticut officials will probably put one or two small casinos in the northern Nutmeg State to reduce the loss of revenue to Massachusetts when the MGM Resorts International casino opens in poor old Springfield. The Connecticut officials worry about the losses to the two Indian casinos in eastern Connecticut caused by incoming eastern Massachusetts casinos and a proposed second Rhode Island casino, in Tiverton.

The idea, of course, in all this is to avoid having to get public revenue honestly by imposing and when necessary raising taxes. It’s far easier to get a slice of a casino’s take, much of which comes from low-and-moderate-income people and much of which goes out of the region to distant owners even as it drains money from local business and increases bankruptcies and crime (especially embezzlement).

Casinos are bogus economic development, but as the tele-evangelists and P.T. Barnum knew well, you can always bet on a surplus of suckers. Let the public get what it wants, good and hard.

-- Robert Whitcomb

Some more wet energy for New England?

Excerpted from Robert Whitcomb's Digital Diary column in GoLocal Prov.

The old line, at least since New Englanders stopped using waterpower to run most of its mills, has been that New England has little in the way of energy sources. That’s been changing for the past few years, with wind turbines and solar arrays popping up. For a while, of course, people held out hope that fracking for natural gas from relatively nearby places, particularly Pennsylvania, would conveniently help address environmental issues and help maintain the region’s energy stability.

But it turns out that the fracking process releases so much methane into the air that it will make global warming considerably worse, although of course it’s less obviously dirty than oil and coal.

An additional source of energy for New England is wave power. (Tidal power is also being worked on.) I used to write about wave power years back when I worked for The Providence Journal. Nine finalists for a U.S. Energy Department award of $1.5 million for wave-energy innovation have been having their technology tested at a Navy wave tank in Carderock, Md.

The DOE estimates that wave power that might be developed off U.S. coasts could provide almost a third of America’s annual electricity use. God knows that the New England’s coastal waters have heavy-duty waves, excluding the bays. Let’s hope that New England-linked companies, such as Sea Potential, with U.S. operations based in Bristol, succeed in getting a big hunk of this business, aided by our local research and development companies and universities. Of course launching these new sources of electricity will pose a challenge to maintaining the region’s electricity grid, which has been based on big gas, oil and nuclear plants.

xxx

The con men promoting casinos as “economic development’’ are relentless, as is the wishful thinking of locals who think that long-run prosperity (and low taxes) will come from hosting a casino in their community. A tour of most casino towns would disabuse them of this idea, an idea that becomes ever more misleading as the gambling market is fragmented by more casinos and the coming of heavy-duty gambling on the Internet.

It should not take a genius to figure out that casinos are parasites sucking money from households and local businesses and sending it to far-away investors. The way to create local wealth is to make, grow or invent stuff, not to get locals to spend their money in a casino. Perhaps this will become clearer to the people of Tiverton, now considering having a casino in that now mostly pretty town.

Tivertonians would do well to drive around some casino towns before they succumb to casino promoters' pitch.

-- Robert Whitcomb

New England's risky bet on a population explosion of casinos

By PEARL MACEK for ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NEWPORT, R.I.

Walk through the automated doors at the Newport Grand Casino and the cacophonic sound of more than 1,000 slot machines greets you. As your ears become accustomed to the multiple layers of sounds, an inundation of vivid purples, blues, reds and yellows flash before you as each machine tries to entice potential players.

Slot machines called “Lucky Larry’s Lobstermania,” “Sex and the City” and “Cleopatra” seem innocent enough, but after you insert your money, a digital message gives you a hotline number to call if your gambling has become problem. Nearby, virtual blackjack dealers, big-breasted women with smiling faces, wait patiently inside their respective screens for real players.

It’s a Thursday evening and the crowd, mostly an elderly one, sits before colorful screens waiting to hit the jackpot. On this particular night, however, the casino isn’t anywhere near capacity, which is probably one of the reasons that the Twin River Management Group (TRMG) wants to close it.

TRMG operates Twin River Casino in Lincoln, a Hard Rock Hotel in Biloxi, Miss., and Arapahoe Park, a horse-racing track in Colorado. The management group officially announced that it had acquired Newport Grand last July, but it was already public knowledge that the company would seek to move Newport Grand’s gaming license to a new site, possibly in Tiverton, which seemed more open to hosting a destination casino.

“When we acquired Newport Grand we acquired it not thinking we would be able to do many things with it other than operate it as it was,” said John E. Taylor Jr., chairman of the board of directors of Twin River Worldwide Holdings, the parent company of TRMG, during a recent phone interview with ecoRI News. “But we wanted to see if there was a possibility that there was another community in a more advantageous location that might consider hosting a facility like this.”

Table games are considered by the gaming world as a vital way of attracting a larger, younger demographic, but twice Rhode Island voters, particularly Newport voters, said “no” to table games at Newport Grand. It seems the last majority “no” vote, in 2014, sealed Newport Grand’s fate.

Gambling with economy

The fiscal 2015 financial report of the Lottery Division of Rhode Island’s Department of Revenue states that $516,262,400 in revenue was generated by video lottery (slot) machines and $106,640,942 was generated by table games. Together, they make up 71.9 percent of the gaming industry in Rhode Island, which brought in a total of $867,054,081 during the last fiscal year.

Rhode Island’s gaming industry is the state’s third-largest revenue source.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2015, TRMG held a series of talks and charrettes in Tiverton to explain to residents the company’s design plans for the proposed casino. According to Taylor, residents seemed receptive to the idea.

“We thought that the market could support 1,000 machines, comparable to the number that they have at Newport Grand, and we thought about 30 table games could be supported,” he said. “But what we told the residents is that we’re having this conversation to see what else you would feel comfortable with.”

In early November of last year, TRMG presented its plan to the Tiverton Town Council: a two-story, 85,000-square-foot facility with an attached 84-room hotel and 1,100 surface parking spaces. The proposed casino would be set on 23 acres on a 45-acre parcel just off Stafford Road and 400 feet from the Massachusetts border.

From this location, it’s a 50-minute drive to Plainridge Park Casino, in Plainville, Mass., and 30 and 43 minutes from Taunton and Brockton, respectively, where two casinos are slated to be built. A $1.7 billion Wynn Boston Harbor casino in Everett also has been proposed.

Taylor said TRMG isn’t too worried about the possibility of three more casinos opening in the area. “Convenience is critical,” he said. “The more convenient that we can make it for people to get to, the better.”

The proposed Tiverton casino would employ between 525 and 600 employees, according to Taylor, and all of Newport Grand’s 175 employees would have the opportunity to work at the casino in Tiverton.

Voters to decide

Earlier this year, both chambers of the General Assembly overwhelmingly approved legislation to give Rhode Island residents the opportunity to vote for or against a Tiverton casino. The legislation was signed by Gov. Gina Raimondo the next day. Questions regarding the casino will be put on the November ballot. The proposal will have to receive a majority “yes” vote from both state voters and Tiverton residents.

Should the ballot questions win approval, the state would receive 15.5 percent of table revenues and 61 percent of video-lottery terminals (VLTs), from both from the new Tiverton casino and Twin River. The legislation would also guarantee each host community $3 million annually from the casinos.

“They (casinos) have been, up to this point, considered to be a real success story, but I do consider the fact that they are such a large part of our state’s revenue to be a real issue for worry and to some extent, a failure of Rhode Island to really get its growth-oriented sectors going,” said Leonard Lardaro, an economics professor at the University of Rhode Island. “What we’re looking at, and I think it is important to put it in this context, is that the gambling industry is very over supplied, very, very oversupplied.”

Patrick Kelly is the chair of the department of accountancy at Providence College. He has studied casinos and their social and economic effects, specifically in the southeastern Connecticut region. Kelly said that in the coming years “there is going to be a lot more commitment to casinos for revenue and jobs,” not just in the Northeast but throughout the United States. He said that is a concern.

By 2018 he expects to see some 60 casinos along the Route 95 corridor between Maine and Maryland, including three or four in Massachusetts, two in Rhode Island and two or three in Connecticut. Kelly said this will ultimately lead to market saturation, but a greater concern of his are the social costs related to having so many casinos, such as problem gambling and an increase in criminal behavior to support gambling addiction.

About 3 percent of the U.S. population is addicted to gambling, while others are hooked by the lure of tax revenue and an economic rescue. (istock)

Addicted to gambling

Tawny Solmere is the director of Problem Gambling Services of Rhode Island (PGSRI). She said that between 1 percent and 3 percent of the U.S. population has a gambling problem, “so that means, with the census of Rhode Island, that we are looking at between 10,000 and 30,00 people” who have problems with gambling.

PGSRI is a hotline service. When people call, they are referred to a counselor at one of the six behavioral health-care clinics run by the nonprofit CODAC Behavioral Healthcare. The lottery subsidizes PGSRI, but Solmere said more help from the state would be welcomed, especially if the casino industry continues to expand.

She noted that co-dependencies, such as drug and alcohol abuse, tend to accompany gambling addiction. But there is an aspect to problem gambling that is particularly egregious. “This disorder, problem gambling, has the highest rate of suicide than any other addiction,” Solmere said.

Solmere said PGSRI and CODAC are neither for nor against casinos, but she is worried that unless more is done to help those with gambling addiction, the situation could easily spiral out of control.

“If we don’t get the resources to meet that need, Rhode Island is going to have an epidemic equal to the heroin epidemic we are looking at now,” she said. “It’s a scary prospect.”

Rep. John Edwards, D-Tiverton, said building the casino in Tiverton “just makes sense” and will offer local residents a large number of employment opportunities. As far as gambling addiction, he said, “You worry a little bit about that,” but, “if they are going to gamble, they are going to gamble somewhere.

“I think that it will be an asset for the Tiverton and the whole East Bay area.”

George Medeiros, a longtime Tiverton resident and owner of Tiverton Sign Shop, agreed. “It’s just something for this area,” he said during a recent phone interview. He noted that there is little to attract people to Tiverton, and for it’s residents, there are few dining and entertainment options.

“For me to get a pizza right now, I would have to go to Fall River or the other side of Tiverton,” Medeiros said.

He said he isn’t worried about traffic congestion, as the casino will be located just off the Route 24 ramp, and according to a TRMG press release from November 2015, the Rhode Island Department of Transportation is planning to build a roundabout on Canning Boulevard with a dedicated turn lane into the proposed casino.

The only thing that worries Medeiros is if the proposed casino in Taunton opens before the Tiverton casino. “They might not be fast enough,” he said.

Brett Pelletier is a member of the Tiverton Town Council and the only one to oppose putting questions about the casino on the November ballot. He also was the only council member to respond to an ecoRI News request for comment.

Pelletier, who is a real-estate analyst with a consulting firm in Boston, was appointed to a Town Council subcommittee to vet the casino legislation and provide feedback before it went to the General Assembly.

“Every time that the meeting was meant to take place, it was canceled for one reason or another,” he said. “We never actually met.”

In regards to Rhode Island’s dependency on the gaming industry, Pelletier said, “I think that it’s an atrocious way to run a government, preying on people who have an unjustified hope that they will strike it rich at a casino.”

Economic impact

The Brockton and Taunton casinos are scheduled to be built by the end of 2018. TRMG has taken the possibility of those facilities opening by then into consideration in its gaming market study.

The company has included four different scenarios, including the Brockton casino entering the market but Taunton doesn’t. The report estimates $127.6 million in revenue if that were to happen. If neither of those casinos opened, the report estimates $147.9 million in revenue for the Tiverton facility.

TRMG has worked closely with the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management to identify developable land, according to the company, and it hired the firm Natural Resources Services Inc. to suggest mitigation plans for any adverse impact on local wildlife.

Rachel Calabro, a community organizer at Save The Bay, said the Providence-based nonprofit has yet to look deeply into the possible environmental effects of a Tiverton casino. She has seen the plans for the site and suggested that they reduce the amount of parking surface area by building a garage instead. The amount of concrete surface space initially suggested for the casino could lead to serious flooding issues, Calabro said.

She also suggested the installation of solar panels.

Casinos in Tiverton, Taunton and Brockton could certainly become go-to destinations, but the continued reliance on this revenue raises legitimate questions: Can the Rhode Island gaming industry continue to be a leading revenue source given the inevitable construction of more casinos in Connecticut and Massachusetts? Will the gaming industry last and will it be worth the social costs?

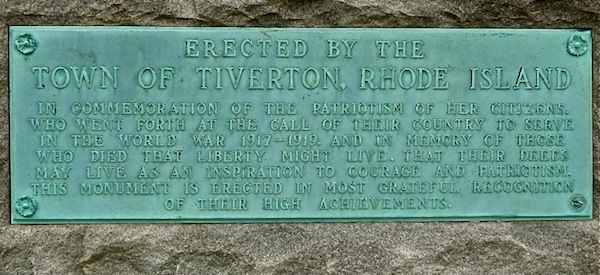

Willliam Morgan: The Doughboys of Tiverton

Commentary and photos by WILLIAM MORGAN

Despite 2014-2018 marking the centenary of World War I, there do not seem to be a lot of celebrations planned. No groups of war re-enactors and their camp followers are rushing to spend several years in the mud to recreate the Battle of the Somme or Passchendaele.

Yet, it was American "Doughboys,'' arriving in France who turned stalemate into victory (and into reparations that laid the foundation for the next great war, but that is another story).

Forgetting the isolationist sentiment that kept the United States out of the war for so long, many towns, such as Tiverton, R.I., erected statues to our heroes.

The Tiverton soldier appears to be defending the long-closed bridge across the Sakonnet River. As war memorials go, this bronze by Lewis J. White and cast by the Gorham Foundry is merely serviceable, neither exceptional nor dramatic.

Nevertheless, it still offers a story. The Roll of Honor lists over 150 names. Could Tiverton have sent so many soldiers and sailors to rescue Belgium and France from the Hun? Of those, over a dozen deaths were noted with little stars.

There are a number of Irish (Brophy, Flanagan, O'Connell), French (Beaulieu, Herveux, Lavault), Portuguese (Medeiros, Souza, Raposa). But what surprises is how a hundred years ago the majority of names were old New England ones–Bradshaw, Stafford, Holden. Four nurses are remembered as well, including Emma Frost and Mary Tabor Manchester.

William Morgan is an author and architectural historian.

![[#Beginning of Shooting Data Section]

Nikon D100

2004/05/08 10:48:19.9

RAW (12-bit) Lossless

Image Size: Large (3008 x 2000)

Lens: 70-300mm f/4-5.6 D

Focal Length: 270mm

Exposure Mode: Programmed Auto*

Metering Mode: Multi-Pattern

1/80 sec](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/561446cce4b094b629347f8d/1475386931853-1WW63UBH0LMA5X4J0LL6/fullsizeoutput_10d27.jpg)