Llewellyn King: The lure of the linemen

From across America an army of men, and a few women, has been on the move. They are deployed with tools and gauges, maps and their own know-how in a critical battle. They are shock troops fighting the flooding in North and South Carolina.

They are electricity linemen.

When disaster strikes, the nation’s electric utilities spring into action, sending equipment — which can range from temporary lighting to the familiar bucket trucks — hundreds and thousands of miles to the battle.

When these first responders reach the site of disaster, they go to work down manholes and up poles, struggle with knotted wires and fallen trees.

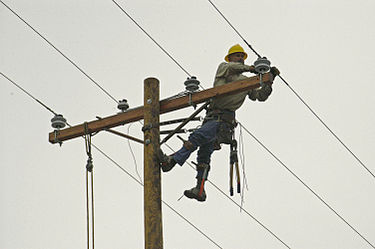

The work is hard and the conditions are dangerous, but there is a camaraderie that binds linemen from different localities in a common purpose and danger. Those who more usually might rely on a bucket truck, in fine conditions, take out their climbing gear and up the pole they go.

The constant danger is electricity itself: the threat of electrocution. Up the pole, there are many other dangers. The pole may be weakened and critters seeking safety may be up there, from raccoons to venomous snakes.

When the lights go off, life as most of us know stops. It does not grind to a slow halt, it stops. Elevators, air conditioners, heating systems, ovens, refrigerators, televisions and computers are stranded. Even the pumps for removing water from a flooded basement need electricity.

Everyone knows that in an emergency, it is vital to restore the juice. The linemen, often several sleeping in a single motel room or in their trucks, are the heroes who work as many as 19 hours straight to do that.

It is rewarding, exacting and well-paid work. A spokesman for the American Public Power Association explains that pay varies, depending on the part of the country, but $100,00 a year is common and earnings shoot up with overtime, as in emergencies. The association represents more than 2,000 publicly owned utilities, serving about 14 percent of the nation’s electricity consumers.

So it is astounding that for a number of years both the publicly owned and the large, investor-owned utilities, which the Edison Electric Institute represents and account for 80 percent of the power supply, have been having a devil of a time finding workers prepared for a generally very secure life that has its moments of high drama — as is the case right now with the crews restoring power to areas devastated by Hurricane Matthew.

The problem is that even the most enthusiastic young person cannot just go up a pole without a lot of training: four years of training.

In the world of labor, electric utilities are not the only ones gasping for help. There is an artisan labor shortage and it is worsening. One truck operator reckons there are vacancies for at least 50,000 truck drivers. Similar shortages exist for electricians, pipe-fitters, sheet metal workers, stone masons, welders and many other skilled artisans.

If all the manufacturing jobs that politicians say that they would like to bring back to the United States were to arrive next year, there would be no workers to build the factories, nor a trained workforce to make the goods. The unemployment crisis — so emphasized in this election year — is with the unskilled.

Part of the artisan problem may be that too many young men and women are being herded into colleges without any knowledge of alternatives for which they might have more aptitude and interest. More college is always seen as a virtue. But who needs four years of college to become an Uber driver?

When the APPA tried recruiting in high schools with a video, they found that teachers trashed the video. Schools are rated on how many graduates go on to college, not on to training in trades offering job security and satisfaction.

There is a future up the pole.

Llewellyn King (llewellynking1@gmail.com) is host and executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a long-time publisher, columnist and international business consultant. This piece first ran in Inside Sources.

Charles Chieppo: Pay for success social programs

To its many critics, President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty is often described as the classic 1960s social program: a well-intentioned but naive effort that spends billions of dollars year in and year out without making much of a dent in poverty.

But imagine if government only paid social-service providers if their efforts actually yielded the desired results. That's the idea behind "pay for success" programs, also known as social impact bonds. Under this concept, businesses and/or philanthropies provide up-front money for programs to address difficult social problems. If they achieve a set of measurable outcomes within an agreed-upon time period, the funders get their investments back, plus interest. If not, government pays nothing.

Pay for success programs seem to be attracting a growing number of bipartisan fans since I wrote about them in 2014, and two new programs illustrate how implementation of the concept is becoming more sophisticated.

Last month, Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy, a Democrat, announced a four-year initiative to keep children from 500 families out of foster care. Social workers from the Yale Child Study Center will focus on parents with substance-abuse problems as part of an intensive effort to keep the children in their homes.

No funder has been named yet for the $12 million initiative, but several have expressed interest. If successful, the state will reimburse the up-front money plus a 5 to 6 percent interest payment. It's a pretty good deal considering that Joette Katz, commissioner of the state's Department of Children and Families, told The Washington Post that Connecticut currently pays about $350 million annually for services to children in foster care and institutions.

In South Carolina, Republican Gov. Nikki Haley recently announced a $30 million, four-year program to send registered nurses who specialize in maternal and child health into the homes of low-income pregnant women to teach them parenting skills and ways to keep their children healthy. The effort is funded by foundations and a corporation.

The Connecticut and South Carolina programs highlight the opportunity pay for success presents for prevention programs that can yield long-term savings but might not get funded through the traditional appropriations process. The South Carolina program also addresses the potentially sticky issue of determining whether a program has achieved the agreed-upon outcomes by designating an MIT research group to conduct an evaluation. Such provisions enhance the integrity and perception of pay for success.

As a model that is dependent on what funders are willing to invest in, pay for success isn't the silver bullet for addressing every stubborn and costly human-services problem. But particularly during a time when some once again seeing economic clouds looming, they can be a valuable tool for helping our neediest citizens by focusing state and local government resources on the best kinds of programs -- those that actually work.

Charles Chieppo is a research fellow at the Ash Center at Harvard's Kennedy School. This originated at governing.com.