While we know a lot about Elliot Rodger, the young man who murdered six, injured 13 others and then killed himself on a rampage in Isla Vista, Calif., on May 23, we still do not know as much as we should to derive all the painful lessons; there are ambiguities galore. But his case has rightly energized the debate about gun laws and the fragmented American mental-health “system.”

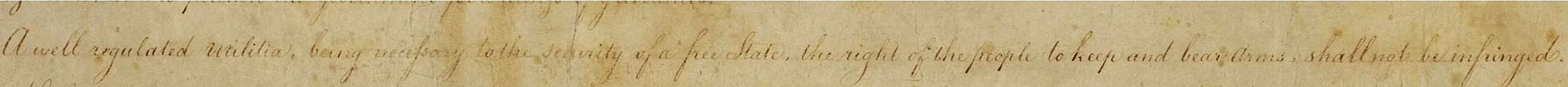

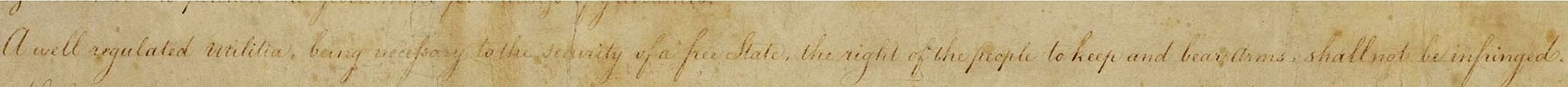

I’d guess that the Second Amendment was far more about state militias than individual possession. Otherwise why did the Founders write in the amendment of the need for a “well-regulated militia” as its justification? (Especially note the phrase “well-regulated.”) Still, the amendment is badly written and it’s impossible to know for sure what the Founders wanted. Meanwhile, the firearms makers and gun-rights absolutists hold sway in Congress, whatever the public-opinion polls, and presumably will continue to do so for the indefinite future. (The one argument that gun-rights absolutists have that I think has a smidgen of sense is that our heavily armed population might make it more difficult for a dictatorship in Washington or outside invader to impose its will. Still, could they defeat military forces?)

Anyway, since the late ’60s and early ’70s, with the new drugs marketed as panaceas for severe mental illness, and the deinstitutionalization movement, which closed many mental hospitals, it’s been increasingly tough to commit people to institutions against their will.

Things got worse with the Health Insurance Portability and Affordability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, a part of which makes it agonizingly arduous for relatives to obtain essential psychiatric and other medical information about adult mentally ill people. We need to make it easier for families to obtain such information and then be able to act on it by obtaining a court order to involuntarily hold people who have shown themselves as potentially dangerous.

Legislation in Congress filed by Rep. Timothy Murphy (R-Penn.), Congress’s only clinical psychologist (Congress needs many more of them!), would help. It would encourage states to commit severely mentally ill people to mental hospitals or mandatory outpatient treatment by, among other things, loosening the privacy rules to give families more actionable clinical facts about troubled relatives.

But unfortunately it fails to speak to the need to build more mental hospitals, both private and state-run. Far too many of the mentally ill will not cooperate in outpatient therapy, be it sessions with therapists and/or taking medication. The fact is that some people need to be committed for long periods, and some for the rest of their lives. And that’s what happens anyway. We use our prisons for this function; at least half of America’s huge jail population is mentally ill in varying degrees, with many out-and-out insane.

At the same time, laws should be changed to more clearly limit the ability of people declared by a judge to be mentally ill to buy guns. Further, there should be more legal mechanisms to let police obtain warrants to take firearms away from people deemed dangerous. (And, yes, I know that Elliot Rodger stabbed to death three of his victims. But it’s far easier and faster to kill people with guns than with any other weapon except of course with what a competent bomb maker could make.) Look at the mass murders of recent years.) As it is, the police have remarkably little legal power to stop crazy people from perpetrating violent crimes.

Will any major reforms involving the interface of guns and the mentally ill actually be implemented? Yes, though it may take a few more massacres. Meanwhile, who will lead to the way to build more mental hospitals to hold and treat people for whom outpatient treatment may be insufficient? Liberals and some libertarians will complain about the threat to civil liberties, conservatives about the cost. But what about the right of citizens not to be imperiled by crazy people walking around, and what about the huge financial cost of law enforcement and incarceration for so many of these people?

***

Thus we begin another summer. (I take June 1 as the real start of the season.) First comes lushness and freshness — “And what is so rare as a day in June?” asked James Russell Lowell, the 19th Century New England poet. He went on, in romantic (corny?) Victorian fashion:

Now is the high-tide of the year,

and whatever of life hath ebbed away

Comes flooding back with a ripply cheer,

Into every bare inlet and creek and bay;

Now the heart is so full that a drop overfill it

Then it gets grittier as we go into July and the lawns turn brown. Then comes a renewed freshness, almost a second spring, but with dimmer light and school-return anxiety (whatever your age) toward the end. Faster and faster comes Labor Day.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) oversees newenglanddiary.com. He is a former Providence Journal editorial-page editor, former finance editor of the International Herald Tribune and former managing editor of several newsletters on mental and behavioral health.