Philip K. Howard: Public-employee unions, unlike trade unions, corrupt democracy

Chicago teachers marching during a demonstration on Oct. 14, 2019

Massachusetts state militia enter Boston’s Scollay Square (RIP) to restore order during the city’s police union strike in 1919, which was broken, in large part by the rigorous actions by Gov. (and later Vice President and then President) Calvin Coolidge. The strike left a negative opinion amongst many citizens about public-employee unions for many years. There was much crime and other disorder during the strike. Coolidge famously said during the strike:

“There is no right to strike against the public safety by anyone, anywhere, any time. ... I am equally determined to defend the sovereignty of Massachusetts and to maintain the authority and jurisdiction over her public officers where it has been placed by the Constitution and laws of her people."

In a runoff election for mayor, Chicago voters on April 4 narrowly chose former teacher Brandon Johnson over former schools CEO Paul Vallas. Raising eyebrows was the funding of Johnson’s campaign: Over 90 percent came from teachers unions and other public-employee unions. Vallas had the endorsement of the police union, but his funding was more diverse, including business leaders and industrial unions. Just looking at the money, the race came down to this: Public employees vs. everyone else plus cops.

What is wrong with this picture? The new mayor is supposed to manage Chicago for all the citizens, not to benefit public employees. Chicago is not in good shape. In 37 of its schools, not one student is proficient in reading or math. Its transit system is stuck with schedules that serve no one at great expense. The crime rate in Chicago is among the highest in the country. But no recent Chicago mayor has been able to fix these and other endemic problems because the public unions have collective bargaining powers that give them a veto on how the city is run. Frustrated by the inability to get teachers back to the classroom during COVID, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot observed that the teachers union wanted “to take over not only Chicago Public Schools, but take over running the city government.”

This is not just a Chicago problem. Los Angeles teachers walked out of class rooms last month supposedly to support striking service personnel, but Los Angeles lacks the resources to help the service employees because of the indebted inefficiencies in the teachers union contract.

American government has a fatal flaw hiding in plain sight. Public employee unions in most states have a stranglehold on public operations. Voters elect governors and mayors who have been disempowered from fixing lousy schools, firing rogue cops, or eliminating notorious inefficiencies.

Look at almost any public scandal in recent years—failing schools in Baltimore, police killings in Minneapolis and Memphis—and you will find public supervisors who, under union controls, have lost basic managerial tools. Democracy is supposed to be a process of accountability. But there’s near-zero accountability in American government—between .01 and .02 percent in most jurisdictions. Two out of 95,000 teachers in Illinois were dismissed annually for poor performance over an 18-year study period. In the decade prior to the killing of George Floyd, of the 2,600 police complaints in Minneapolis only 12 merited discipline, of which the most severe was a 40-hour suspension.

No wonder democracy is working so badly. Elected leaders come and go, but public unions just say no. How did public employee unions get this power?

Rewinding the Clock

Until the 1960s, public employees were organized like lawyers, doctors and other voluntary professional associations. They had no legal right to compel government to enter into contracts. Many already enjoyed civil service protections, and government work was generally sleepy, not ruthless. But public employees had become a huge voting bloc, and leaders of public employee associations wanted power over how government was run.

Until then, the idea of public employees bargaining against government was inconceivable. FDR, a strong supporter of trade unions, firmly rejected government bargaining: “The process of collective bargaining…cannot be transplanted into the public service.” Early labor leader Samuel Gompers refused to let police join the industrial union because, having sworn to serve the public, police would have a conflict of interest. As late as the 1950s, union leader George Meany stated unequivocally that it is “impossible to bargain collectively with the Government.”

But the strong tide of the 1960s rights revolution provided ample cover for government unions to get similar statutory powers as industrial unions. No one conceived back then that these powers would make government unmanageable. It was just considered a matter of “elementary justice” to treat them the same.

Government bargaining, however, is radically different from trade union bargaining:

A trade union must honor efficiency, or else the jobs are lost when the business moves out of town or fails. Government can’t go out of business or move, so public employee bargaining is aimed at creating deliberate inefficiencies to foster more jobs.Multi-hundred-page contracts that are designed for featherbedding and overtime excesses. Taxpayers must foot the bill.

Trade union bargaining is limited to dividing the pie of profit between capital and labor. There is no profit in government, so the scope of government bargaining has no defined limits. Again, the taxpayers must pay.

In trade union bargaining, it would be unlawful for management to collude with a complicit workers group. In government bargaining, overt collusion is how the game is played. In exchange for huge union campaign support, politicians agree to give unions control over public operations and pensions. As unions like to say, “we elect our own bosses.” At a rally with public unions, New Jersey’s then-Governor Jon Corzine called out that “We will fight for a fair contract!” Who was he going to fight? Collective bargaining with government unions is not a real negotiation. It’s a pay-off.

For fifty years, government union controls have gotten ever-tighter. Unlike all other interest groups, government unions have a binding contractual veto over how government operates, and are first in line for public resources. They keep it that way with preemptive political force. Stanford political scientist Terry Moe found that in 36 states teachers unions contributed more than all business groups combined.

The Disempowerment of Elected Executives

Newly-elected governors and mayors in most states quickly discover that they have no managerial control over schools, police, and other government operations. If an elected executive has the backbone to try to buck the union, and restore managerial powers when an agreement comes up for renegotiation, the executive in many states will find that unelected arbitrators have the final say.

Near-zero accountability makes its practically impossible to transform a lousy school, or an abusive police culture, because the supervisor can’t enforce good values and standards. No accountability also removes the mutual trust needed for any healthy organization. Why try hard, or go the extra mile, when others just go through the motions? The absence of accountability is like releasing a nerve gas into the agency or school.

Rigid work rules guarantee massive inefficiency. Basic services such as trash collection, and road and transit maintenance, cost two to three times what it would cost in the private sector. Need someone to help out or fill in? Sorry, not permitted. Need teachers to do remote teaching during the pandemic? There’s nothing about that in the agreement, so it must be negotiated.

No public purpose is served by union controls. Nor do union controls make government an attractive employer. Good candidates are repelled by toxic public cultures without energy or pride. Union controls serve only to transfer governing authority to union officials, who exercise that authority mainly to pad public employment and insulate government workers from supervisory judgments.

Public unions have turned public operations into a permanent spoils system: Unions have control over public operations and have insulated public employees from accountability, no matter how poorly they perform. That’s why democratically-elected leaders almost never fix what’s broken.\

All government employees should realize that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service. It has its distinct and insurmountable limitations when applied to public personnel management. The very nature and purposes of government make it impossible for administrative officials to represent fully or to bind the employer in mutual discussions with government employee organizations. The employer is the whole people, who speak by means of laws enacted by their representatives in Congress. Accordingly, administrative officials and employees alike are governed and guided, and in many instances restricted, by laws which establish policies, procedures, or rules in personnel matters. Particularly, I want to emphasize my conviction that militant tactics have no place in the functions of any organization of government employees. Upon employees in the Federal service rests the obligation to serve the whole people, whose interests and welfare require orderliness and continuity in the conduct of government activities. This obligation is paramount. Since their own services have to do with the functioning of the government, a strike of public employees manifests nothing less than an intent on their part to prevent or obstruct the operations of Government until their demands are satisfied. Such action, looking toward the paralysis of government by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, writer and civic leader, is author most recently of Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions (Rodin Books, 2023). He is chairman of Common Good (commongood.org), a legal-and-regulatory-reform organization.

Read here Franklin Roosevelt’s views on public-employee unions.

Philip K. Howard: Our governing processes have become paralytic, and what to do about it.

The Bayonne Bridge, where an urgently needed improvement has been blocked by inane regulatory red tape.

Crook Point Bascule Bridge (1908), once connecting Providence and East Providence, R.I. It’s been stuck in upright position since 1976.

— Photo by Matthew Ward

Governing is not a process of perfection. Like other human activities, governing involves tradeoffs and trial and error. One of the most important tradeoffs involves timing. Delay in governing often means failure. Nowhere is this more true than with environmental reviews for infrastructure. Every year of delay for new power lines, modernized ports, congestion pricing for city traffic and road bottlenecks means more pollution and inefficiency.

New York Times columnist Ezra Klein has awakened liberal readers to the reality, hiding in plain sight, that governing processes are paralytic: “The problem isn’t government. It’s our government. … It has been made inefficient.”

The other week columnist George Will asked whether America “can do big things again.” Citing our work, and the absurd 20,000-page review for raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, which connects Bayonne, N.J., with New York City’s Staten Island, to permit new post-panamax ships into Newark Harbor, Will calls out “the progressive aspiration to reduce government to the mechanical implementation of an ever-thickening web of regulations that leaves no room...for judgment.” American Enterprise Institute scholar and Washington Examiner columnist Michael Barone, also citing our work, the other day called for a rebooting of government to “sweep out the ossified cobwebs.”

The recent $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure law contains tools to streamline permitting, including presumptive 200-page limits on environmental reviews and two-year processes that we championed. But actually giving permits requires officials to use their judgment about priorities and tradeoffs, not to overturn every pebble. That may be a problem in current bureaucratic culture. In a letter to the editor of The Washington Post, an environmental official objects to my suggestion that raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge using existing foundations “involved no serious environmental impact.” He asserts that “bringing larger, more polluting ships and increased cargo” to the port “would result in increased diesel pollution from both the ships and the trucks transporting the cargo.”

Actually, the new larger ships are much cleaner, pollution-wise and burn much less diesel fuel per container. That’s a reason they’re more efficient. Increasing the capacity of the Newark port will indeed result in more truck traffic, but those containers have to come in somewhere.

You start to see the problem. It’s impossible to talk about environmental impact in the abstract. What’s needed is a governing culture that can make judgments about practical tradeoffs.

In a piece for Fortune on efforts to protect kids online, Jonathan Haidt and Beeban Kidron cite my work on the benefits of a principles-based approach to writing laws.

Julia Steiny in the Providence Journal cites my work in describing how Providence public schools are being crushed by law: “The system suffers from what author Philip Howard calls The Rule of Nobody. He says that the law operates ‘not as a framework that enhances free choice but as an instruction manual that replaces free choice.’”

For the American Spectator, E. Donald Elliott provides a history of Common Good’s effort to bring about infrastructure permitting reform.

Philip. K. Howard is a New York-based lawyer, civic and cultural leader, author and photographer. He’s chairman of the legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org) and the author of, among other books, The Death of Common Sense and The Rule of Nobody.

Philip K. Howard: How to fight back against the forces that are tearing apart America: End the ‘vetocracy’

Trump supporters crowding the steps of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 as they prepare to force their way into it to try to overturn the election won by Joe Biden.

— Photo by TapTheForwardAssist

NEW YORK

What can we do about our country? That’s the question I hear most often. Washington is mired in a kind of trench warfare, with no prospects of forward movement. And Americans today can be divided into two camps: discouraged or angry.

Americans are retreating into warring identity groups as extremists demand absolutist solutions to defeat the other side. It’s nighttime in America.

Yet, Americans still share basic values of self-reliance, tolerance and practicality, surveys show. Put Americans in a crisis, and unfailingly they put themselves on the line to help their fellow citizens, as essential workers did during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Do we really hate each other? I don’t think so. We’re being forced apart by organized forces that profit from polarizing the country.

Extremists have the stage, and are relishing their new power to cow reasonable people into unreasonable positions — whether to deny the results of elections or benefits of vaccines, or to demand that most Americans wear hair shirts because of the sins of their ancestors.

Political insiders are manipulating extremism to their own goals. Political parties no longer compete by accomplishment but by stoking fears that the other side is worse.

The bottom line: Washington will not pull America back from the extremist precipice.

New leaders are obviously needed. But new leaders are not sufficient. Remember that Barack Obama promised “change we can believe in.” When that didn’t work out, frustrated voters (albeit with almost 3 million fewer votes than Hilary Clinton got) elected his polar opposite, Donald Trump, who promised to “drain the swamp.” Nothing much changed except more frustration, leading to greater extremism.

A new governing vision is needed – one that appeals to common interests while also responding to our frustrations. To talk polarized Americans off the precipice, we must understand how we got to the edge of this cliff.

The root cause of extremism, throughout history, is often a sense of powerlessness. Humans have an innate need for self-determination and opportunity. Can you do and say what you think makes sense? If not, sooner or later, you will want to break out. The Tea Party, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, Stop the Steal: All these recent movements are ignited by a sense of powerlessness.

Government controls decision-making

What Obama and Trump failed to comprehend is this: The operating philosophy of modern government does not honor the role of human judgment in social activities. Instead of providing an open framework of goals and principles, activated by people taking responsibility, government strives to supplant human agency altogether.

At every level of society, Americans have been disempowered from making the choices needed to move forward. The operating structures of modern society are versions of central planning – dictating exactly how to do everything.

Why do Americans feel powerless? Because they can’t make a difference, and neither can their elected officials.

A new governing vision is needed to address this powerlessness. What I propose is to restore the human responsibility model that the Framers envisioned. As James Madison put it, giving responsibility to “citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country.”

Law should set goals and boundaries, but leave implementation to responsible people. Our protection from bad choices is accountability, not mindless compliance. "No man is a warmer advocate for proper restraints," George Washington wrote, but you cannot remove “the power of men to render essential services, because a possibility remains of their doing ill.”

Building an open governing framework activated by human responsibility is not difficult – it’s far easier to articulate goals than to dictate the details of implementation. Look at any organization or agency that works tolerably well, and you will find people focusing on the goals, not legalities.

But this new governing vision represents a radical departure from the status quo. No longer can bureaucrats avoid responsibility by being sticklers for rules. No longer can one lousy teacher or loud parent get what they want by demanding their rights. People in charge will actually be in charge, and will be empowered to act on their judgment. Other people will be empowered to make the judgments to hold them accountable.

America has become a 'vetocracy'

The federal government will never return willingly to a governing philosophy built on the foundation of human responsibility. All the detailed rules and red tape may prevent forward progress, but they empower insiders to block anything they don’t like. The power in Washington is the power of veto – a governing structure that political scientist Francis Fukuyama calls a “vetocracy.”

Change must come from the outside. The vision for change is to replace red tape with human responsibility. Let Americans use their judgment again. Instead of compliance, give people freedom to hold others accountable.

This is how a free society and democratic government is supposed to work. Instead of driving Americans into warring camps by trying to force one conception of the good, this vision can unite Americans by empowering them to shape their own conception of the good within broad legal boundaries.

Allow Americans to make things work again, and the darkness will soon turn into morning.

Philip K. Howard, a lawyer, author, New York civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder and chairman of Common Good, a legal- and regulatory-reform nonprofit organization. His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left. Mr. Howard is a friend and former colleague of New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, who has worked on several Common Good projects in the past.

Philip K. Howard: Reframing Andrew Yang’s ideas for a new political party

Andrew Yang

Every so often, a citizen emerges to challenge the political establishment. Ross Perot’s 1992 presidential run drew on a public hunger for a new approach; he received 20 percent of the vote. In 2016 Donald Trump steamrolled traditional Republican candidates and changed the party’s face to his own. Andrew Yang is more a firecracker than a depth charge, but he has captured the public imagination with his refreshing candor and fearlessness.

Unlike Perot or Trump, Yang came from nowhere—no public reputation, no big money, no access to any part of the establishment. Yet, by force of his personality, Yang now has a pedestal in the political landscape. In his new book, Forward: Notes on the Future of Our Democracy, Yang plants the flag of a new political party. He argues that, though Americans are not as polarized as polls suggest, neither existing party will address the legitimate needs of the other side. He also says that the two parties are comfortable with their duopoly of failure—first you fail, then I fail—and therefore will not support disruptive electoral reforms such as ranked-choice voting.

Yang is not the first to suggest that our two political parties no longer represent most Americans. Frank DiStefano, in his recent essay in these pages, argued that the parties are on “a locked-in path to destruction and decline.” In my 2019 book, Try Common Sense, which Yang cites, I said that each party’s outmoded ideology precludes the overhauls needed to respond to public frustration.

It is no surprise that a plurality of voters now identifies as “independent” or as a member of a third party. But the electoral machinery makes it difficult for a would-be candidate to operate outside the two parties; and the primary system promotes extremists, not problem solvers.

Yang’s idea of a party is, initially, not one with its own candidates but a centrist movement that exercises influence on candidates from both parties. As DiStefano elaborates it, a movement that captures public imagination can eventually take over or supplant one of the parties. The challenge is to galvanize public support for this type of new overhaul movement in a political environment like today’s, which breeds deadlock, not solutions. While many Americans might be receptive to a new party, the current political shouting match has left them exhausted and cynical. There is a huge gulf today between wanting change and rolling up your sleeves to force change.

So, what does it take to engender the excitement needed for a new movement? Yang proposes a six-point platform for his Forward Party:

1. Ranked-choice voting, with open primaries: These arrangements would reduce the stranglehold of the two parties and defang the extremists.

2. Fact-based governing: The idea here is to evaluate programs objectively.

3. Human-centered capitalism: Yang wants to re-center business around employees and communities, not just owners.

4. Effective and modern government: Here Yang embraces the need to “fix the plumbing” of paralyzed government.

5. Universal Basic Income: Giving Americans $1,000 per month was Yang’s signature proposal in his presidential campaign—a proposal that was validated, he argues, by the Covid relief payments.

6. Grace and tolerance: Yang urges Americans to be more accepting of each other, not stay locked in a battle of identity politics.

By opening the door to a new party, Yang once again reveals solid leadership instincts. But a new movement requires a tougher, more focused platform. A list of centrist do-good reforms is unlikely to elicit the public passion needed to dislodge the current parties. Yang himself is a bold and disarming figure; his party must be as well. A new party needs a clarion call that can galvanize popular support—as the Progressive Movement did, for example, with its vision of public oversight of food and fair practices, or the New Deal with its idea of social safety nets. Successful movements also energize public passion by fingering villains, as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street did.

To get Americans out of their easy chairs, the new party must light a bonfire. Yet Yang’s platform is soporific, with no inspirational theme or evil targets. What’s the vision? Who are the enemies? Here is the way I would reframe Yang’s proposed Forward Party.

First, the clarion call for a new way of governing: Responsibility for America. Americans have lost their sense of self-determination. We should be re-empowered to make a difference. Revive individual responsibility at all levels of society. Replace mindless bureaucracy with accountability for results. Teachers should be free to do their best, with authority to maintain classroom discipline. Principals should be free to hold teachers accountable, and the same should hold true all the way up the chain of responsibility. Officials must be free to authorize action within a reasonable timeframe; and they, too, must be accountable up the chain of responsibility. Mayors and police chiefs should have authority to manage the police force and other departments, including authority to promote public employees who do their jobs and fire those who don’t.

Reviving human responsibility requires overhauling government’s operating systems, replacing thick rule books with simpler goals and principles managed by people who take responsibility for themselves and are accountable to others. This is not so hard: It is far easier to agree on goals than to bicker over endless details of implementation. Modern American government has become basically a bad form of central planning, tying Americans into knots of red tape. Ask any teacher or doctor. Restoring responsibility would empower officials and citizens to govern better and adapt to local needs.

Second, identify enemies and attack them. Powerful forces will resist a movement to revive responsibility. I see two main villains: public unions, which exist to block all accountability, and the political parties themselves, which have become organs of identity politics and special interests. It is impossible to fix broken government or revive a shared sense of national purpose without defeating these villains.

Public unions have made government unmanageable and must be outlawed. Public unions have preempted democratic governance. Citizens elect leaders to run the police force and schools, but these leaders have no authority to fulfill this responsibility. The Minneapolis mayor appointed the police chief; but under the police union’s collective-bargaining agreement, the mayor lacked authority to fire the rogue cop who killed George Floyd—or even to reassign the officer. Unlike private unions, which are dependent on the success of a private enterprise, public unions retain power even where they cause government to fail miserably.

Democracy is supposed to be a process of giving officials responsibility and holding them accountable. But public unions have broken the links: Today, there is zero accountability in the daily operations of American government. Without accountability, rote compliance with the thick rule books replaces individual responsibility for results. The bottom line today is a government bogged down in a bureaucratic jungle of dictates and entitlements. Nothing much works sensibly or fairly because no one is empowered to make things work.

As for political parties, they compete through failure, not achievement. Party leaders have basically given up on reforming government. Instead, they take turns in power pointing to the failures of the incumbent. In 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump tapped into broad public frustrations with Washington. Trump’s erratic leadership opened a door through which Joe Biden entered, offering sanity. But Biden’s failures of execution in Afghanistan and on the Mexican border now empower Republicans to go on the attack and prepare for their own return.

This spiral of negative democratic competition is accelerated by the rise of extremism: Each side stokes fear of the extremists on the other (“Defund the police!” “Stop the steal!”). Actually fixing government is no longer the way the parties compete.

Each party will aggressively resist reforms that would revive responsibility. Public unions have a stranglehold on the Democratic Party. Identity groups on the left will resist any accommodation of other points of view, or what Andrew Yang calls “grace and tolerance.” Republicans have become a party of nihilism and offer no discernible governing vision. They will rail against any reform that empowers public officials, opens elections to moderate candidates, or imposes taxes for public projects.

The existing political parties are the problem, not the path to a solution. The new party envisioned by Yang must ultimately supplant one of them. The new party must ask its supporters to defeat the defenders of the status quo: They are not the agents but the enemies of a successful future. Generating public enthusiasm will require not a laundry basket of reforms but a spear with a sharp point. No matter which party is in charge, focus on its virtually unblemished recent record of failure.

America needs a new party. Its vision must be condensed into a new governing principle that resonates with American values and represents a clean break from bureaucratic paralysis—a principle like human responsibility, which can guide an overhaul of all levels of government.

The current state of American politics has squeezed all energy and hope out of our democracy. There’s no oxygen to serve as fuel for anyone who wants to do what is needed. Yang has cracked open a door, but we need a new vision to open it wide and attract a public enervated by decades of failure.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, author, civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder of the government- and legal-reform nonprofit organization Common Good (commongood.org) and author, most recently, of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left (2019). This essay first appeared in American Purpose.

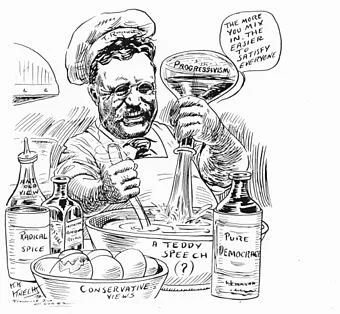

Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party’s (aka “Bull Moose Party’’) presidential candidate in 1912, mixing ideologies in his speeches in this 1912 editorial cartoon by Karl K. Knecht (1883–1972) in the Evansville (Ind.) Courier. The former president’s running mate was California Gov. Hiram Johnson.

Philip K. Howard: A way to make Biden infrastructure program work as hoped

Construction crew laying down asphalt over fiber-optic trench, in New York City

— Photo by Stealth Communications

The Bourne Bridge and the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge at sunset. The Bourne Bridge, at the canal’s western side, and the Sagamore Bridge, to the east, both built in the Thirties, are slated to be replaced.

President Biden’s breathtaking $5 trillion infrastructure agenda — about $50,000 in debt for each American family — is stalling on broad skepticism on both the goals and means of spending that money. There’s bipartisan agreement on at least some of the goals: Spending $1.2 trillion to fix roads, build new transmission lines, expand broadband, and provide clean water could improve American competitiveness as well as its environmental sustainability.

There’s a deal to be made here: Use this moment to overhaul how Washington spends money. Skeptics are correct that, otherwise, most of the money will go up in smoke. What’s needed is a new set of spending principles, based on the principle of commercial reasonableness, enforced by a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board.

The key to governing is implementation. Big talk in press conferences rarely results in success. Nor does throwing money at a problem. The chaos in Afghanistan reveals what happens when top-down dictates are not accompanied by a practical plan for executing the goal. But the Biden administration has no plan on how to implement its infrastructure proposals wisely.

What is certain is that, without reform, most of the infrastructure money will be wasted. Red tape, delays, rigid contracting rules, entitlements and other inefficiencies guarantee that American taxpayers will receive less than 50 cents of infrastructure value for each dollar. That’s optimistic. Comparative studies of infrastructure costs in developed countries show that public transit in the U.S. can be four times as expensive as in, say, Spain or France. A highway viaduct in Seattle cost three times more than a comparable project in France, and seven times more than one in Spain.

What causes the waste? No U.S. official has authority to use commonsense, at any point in the process, to build infrastructure sensibly. Other countries have “state capacity”— a euphemism for public departments where officials are given the authority to make contract and other decisions comparable to their counterparts in the private sector. In America, by contrast, officials’ responsibility is preempted by red tape.

Here are some of the main drivers of waste:

- Permitting can take years because no official has authority to 1) limit environmental reviews to important impacts; 2) resolve disagreements among competing agencies; or 3) expedite resolution of lawsuits. In our study Two Years, Not Ten Years we found that delay alone can more than double the effective cost of projects.

- Rigid procurement protocols strive to detail each nut and bolt in advance, limiting the flexibility needed to confront unanticipated issues inherent in any complex construction project. This leads to massive waste as well as costly change orders.

- Union collective-bargaining entitlements have accumulated over the decades, for example, requiring twice as many workers as needed to operate the tunneling machine for a New York subway. Work rules are designed not for safety or efficiency, but to provide compensation even where there’s no work.

- Legislative mandates further increase the cost of public projects. The “Buy American” laws can increase costs by 25 percent, sometimes more. The Davis-Bacon Act from 1931 increases labor costs by upwards of 20% over market by requiring “prevailing wages”— which is a euphemism for highest wage that can be justified. An army of Washington bureaucrats has the job of dictating wage rates and benefit packages in hundreds of construction job categories in each of 3,000 designated labor markets in the U.S.

- All these legal processes, rigidities and entitlements provide grounds for a lawsuit for any unhappy bidder, contractor, labor union, or environmental group. Lawsuits not only add costs to delay projects, but are commonly used as a weapon to extract payments and concessions that further raise the costs.

Thick rulebooks have supplanted human responsibility. Washington allocates money, with lots of legal strings. It then gives grants to states and localities, many of which are actuarily insolvent – precisely because they cannot manage their public unions and other interest groups. Time passes. Lawyers and consultants produce environmental impact statements. Various groups object and threaten lawsuits. Unions demand ever-greater benefits. Understaffed civil servants try to write procurement guidelines that anticipate every detail and eventuality. The low bidder wins, even if the bidder has a lousy record. Some infrastructure gets built, often badly, and always at a cost that far exceeds what a commercial builder would have paid. The waste here is a scandal — political leaders might as well take taxpayer money and throw it in the fireplace.

How should infrastructure be built? What causes waste in building infrastructure, as NYU’s Alon Levy puts it, is “rigid[ity], where what is needed is flexibility and empowerment” of officials with responsibility. Someone needs to be in charge of each project, and whoever’s in charge needs to have the flexibility to negotiate contracts, adapt to new conditions, and, above all, not to be hamstrung by unrelated requirements.

Building roads, bridges and power lines isn’t rocket science. Other countries and private companies know how to do this. Most public engineers know what performance standards are required. By the simple mechanism of empowering public servants to take responsibility, Levy found, other countries are able to “spend a fraction of what the US does on the same bridge or tunnel.”

Giving officials flexibility to use their judgment, however, requires a mechanism to overcome Americans’ distrust of government. That’s what keeps America’s byzantine bureaucracy in place. Any effort at reform is resisted by groups who argue “What if... an official is on the take?” “What if…the official is Robert Moses, and wants to bulldoze poor communities?”

Opponents to spending reform are mobilizing as I write. The $1.2 trillion Senate bill includes permitting reforms that seek to limit the permitting process to two years. But even this modest reform is under attack by “environmental justice” groups who argue that two years is insufficient to consider those issues. Similarly, a reform to expedite permits for interstate transmission lines is being vigorously opposed by the state energy regulators. They pluck the strings of distrust. But their real objection is that minimizing delay removes the legal veto which they use to extract lucrative benefits for themselves.

What’s needed to overcome distrust is a nonpartisan oversight body that is empowered to avoid waste and corruption. In other developed countries, most citizens accept official authority. But Americans don’t. Creating a trusted oversight institution means it can’t be in the control of either political party. An example are the nonpartisan “base-closing commissions” which decide which defense bases should be shuttered.

I propose a nonpartisan National Infrastructure Board, analogous to oversight boards in Australia and other countries. Its responsibilities would be not to build infrastructure but to oversee and report on how infrastructure is built. Funding could still go through states, but only on condition that timelines and contracts meet standards of commercial reasonableness. No more featherbedding. No more payoffs. States would lose funding if they continued current practices.

The power of a trusted oversight body is exponentially greater than its size. The availability of accountability, not micromanagement, is the element that avoids waste while instilling trust and confidence that everyone is doing their part.

America is at an institutional crossroads. Nothing much works as it should because no official, or teacher, or hospital administrator, or manager, is authorized to make sensible choices. Pruning the jungle of red tape never works because the underlying premise is to avoid human judgment on the spot. The only solution is to replace the jungle with a simpler framework activated by human responsibility and accountability. But who will oversee those officials? That’s why a trusted oversight body is essential.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, author and chairman of Common Good, a bipartisan reform coalition. This piece first ran in The Hill.

Philip K. Howard: Of obsolete laws and the filibuster

Anything positive that comes out of Congress is big news, as with the recent bipartisan support for a $1 trillion infrastructure package. But that’s only half the job: Congress must also fix the delivery system that delays permitting and guarantees wasteful procurement. For example, building a resilient, interconnected power grid — probably the top environmental priority—is basically impossible in a legal labyrinth that gives any naysayer multiple ways to delay, and then to delay some more.

Congress has responsibility not only for enacting new laws, but for making sure old laws work sensibly. But Congress rarely fixes old laws. Congressional oversight consists of posturing at public hearings, not corrective legislation. Congress has effectively abdicated the oversight job to the executive branch and federal courts, which have inadequate authority to make needed legal repairs. The ship of state, weighed down by a century of statutory barnacles, plows slowly in the same direction year after year.

No statutory program works as it should. Infrastructure permitting can take a decade. Health care is a tangle of red tape, consuming upwards of 30 percent of total cost; that’s $1 million per doctor. In about half the states, teachers are outnumbered by noninstructional personnel, many focused on legal compliance. Accountability of public employees is nonexistent; 99 percent of federal employees receive a “fully successful” rating. Obsolete laws notoriously distort resources; the 1920 Jones Act, for example, makes it more expensive to build offshore wind turbines because of its requirement to use U.S.-built ships.

Washington is overdue for a spring cleaning. Only Congress has the authority to do this. But neither party has a vision about how, or even whether, to fix broken government. Congressional leaders are so dug in arguing about the goals of government that they have no line of sight to how laws actually work.

The partisan myopia is revealed by the current debate over whether to retain the Senate filibuster rule. Making it hard to enact new laws, supporters of a supermajority vote argue, encourages more deliberative new programs. Eliminating the rule, on the other hand, will allow narrow Democratic majorities to enact sweeping new progressive programs. These arguments pro and con presume that lawmaking is an additive process — that Congress’s main responsibility is to enact new programs.

Fixing old programs, however, also requires lawmaking. Should Senate rules discourage repairing existing programs? Conservative scholar F.H. Buckley argues for abolishing the supermajority entirely, even though that would mean more liberal programs in the Biden administration, because making it easier to repeal or fix broken laws would be far more impactful.

Debate over the filibuster provides an opportunity to rethink how Congress does its job. The constitutional separation of powers is designed to make it hard to enact new programs. But the Framers also knew that it was important to purge old laws. James Madison believed that “the infirmities most besetting Popular Governments…are found to be defective laws which do mischief before they can be mended, and laws passed under transient impulses, of which time & reflection call for a change.”

But the Framers did not focus on the fact that, once enacted, a program will be defended by an army of interest groups. That’s why It is more difficult to repeal or amend a law than to enact a new one. The determined defense of an obsolete program by a special interest, as economist Mancur Olson explained, will always trump the general interest of the common good. That’s why farm subsidies continue 80 years after the Great Depression ended.

All laws have unintended consequences. Circumstances change. Priorities need to be reset to meet current challenges. Agencies deviate from their congressional mandate. Clear lines of authority must be clarified to give infrastructure permits on a timely basis.

Congress must come up with a practical way to fix broken and obsolete programs. One procedural change might be for the Senate to eliminate the supermajority vote for amending or repealing laws. But the backlog of broken programs is too piled up to expect much impact from one procedural change. Congress needs to go further. Here are three changes specifically aimed at fixing broken laws:

Create nonpartisan “spring cleaning commissions” to recommend updated frameworks in each area. Then, as with base-closing commissions, the proposals would be submitted for an up-or-down vote by each chamber.

Require a sunset on all laws with budgetary impact. Over the course of a decade, Congress could then methodically update the statute books.

Revive “regular order” in Congress to provide more presumptive authority to congressional committees to fix old laws. Congress could further empower committees by automatically approving amendments that are supported by both the majority and committee ranking members.

The failure of Congress to take responsibility for the actual workings of its laws is beyond serious dispute. By delegating lawmaking to agencies, and abandoning effective oversight, Congress has severed the critical link to democratic accountability. Government keeps going in the same direction, no matter how unresponsive and ineffective. Its inability to adapt to public needs in turn spawns extremist candidates. In order to restore trust in Washington, Congress must change the rules so it can take responsibility for how laws actually work.

Philip K. Howard is a lawyer, author, New York civic and cultural leader and chairman of Common Good, a legal and regulatory reform organization that emphasizes the importance of taking institutional, political and personal responsibility. His Latest Book is Try Common Sense. This essay first ran in The Hill.

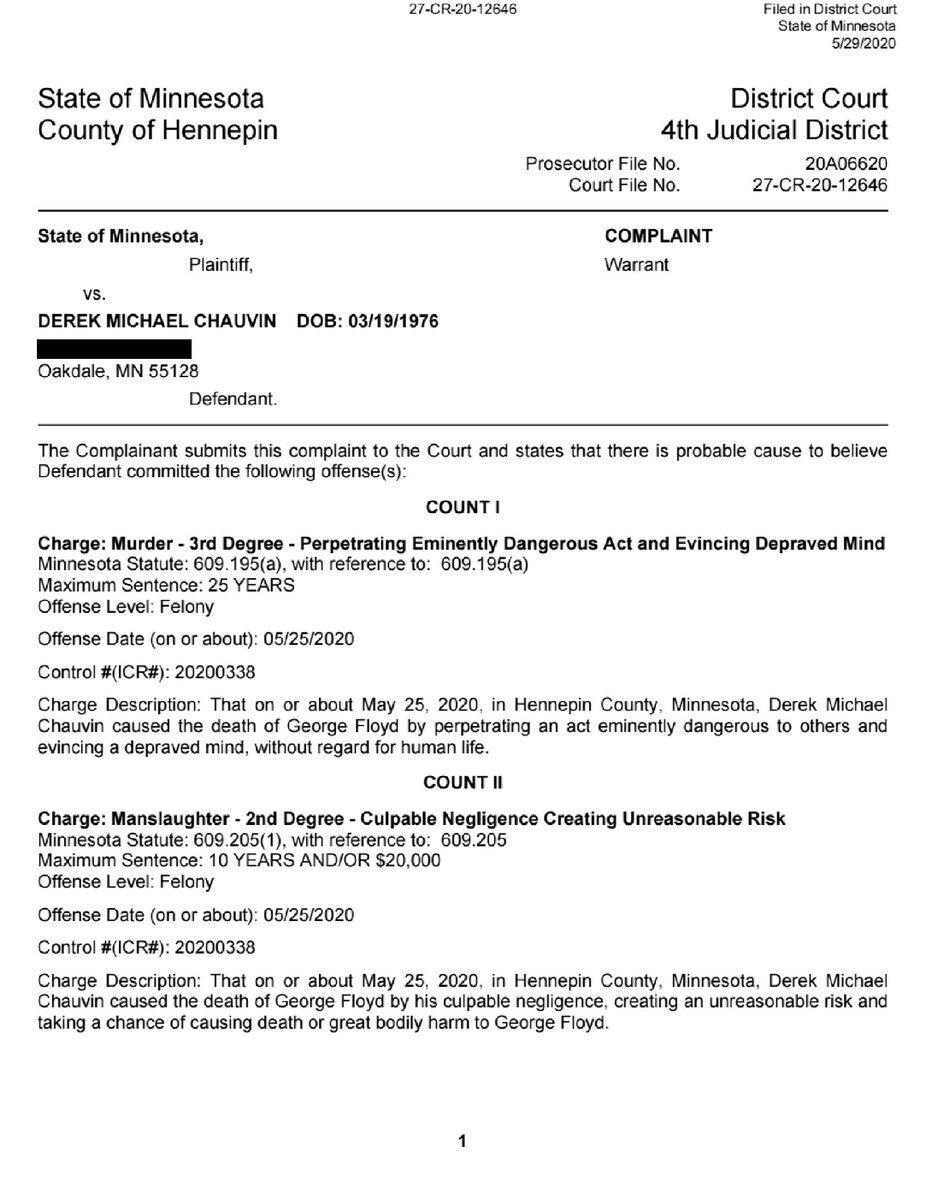

Philip K. Howard: Paralyzing ‘rights’ are used against the public interest; bring back fair accountability

The conviction of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for killing George Floyd may elevate trust in American justice, but it will do little, by itself, to repair trust in police. Nor can political leaders and their appointees do much to restore that trust, because police “rights” still render officers virtually immune from accountability and basic management decisions. Chauvin was known to be “tightly wound,” and the police department had previously received 18 complaints about him abusing his power. Despite the complaints, he was not terminated or transferred. He had his rights.

But what about the public’s rights against abusive officers? We should be protected from bad cops, of course, but we can’t get there using the language of rights. Analyzing public accountability as a matter of rights is circular: Whose rights?

Rights rhetoric sprung out of the 1960s to defend freedom against institutional discrimination. But rights have evolved into an offensive weapon against the legitimate interests of other citizens—by police to avoid accountability, by teachers to avoid returning to work, by journalists and academics to cancel offensive speech.

The fabric of a free society is torn by these self-interested rights. Upholding values like fairness, reciprocity, and mutual respect is difficult when individual rights preempt the rights of everyone else.

The solution is simple: Hold people accountable again. Take “tightly wound” cops off the beat. If college students cancel other students’ freedom to hear a speaker, invite the cancelers to matriculate elsewhere. Healthy teachers who claim their potential covid exposure entitles them not to teach should find other jobs: Why should they be more privileged than nurses and grocery clerks?

But there’s a hitch: Holding people accountable is claimed to violate their rights. We seek more justice, fairness, and freedom, but we deny ourselves the tool of accountability needed to accomplish these goals.

It’s time to reset the balance between public accountability and concerns about individual fairness. Accountability must be taken out of the penalty box: Restore the freedom, up and down the chain of responsibility, to make judgments about other people and their actions. We can provide safeguards against unfairness, but law should intercede only where there is systemic discrimination or demonstrated harassment.

A Condition of Freedom

Every day, each of us evaluates the people we deal with. These judgments about other people influence how we associate, come together, and strive to achieve our private and societal goals.

People judging people is the currency of a free society.

We think of accountability in its negative sense—as the stick for inadequate performance. But accountability is needed for a positive reason—to instill the mutual trust that everyone is doing their share. It assures mutuality of effort and values. Coworkers need to believe that energy, virtue, and cooperation will be rewarded while mediocrity, indifference, and selfishness will not be tolerated.

The paradox of accountability is that once it’s available, it rarely needs to be exercised. What’s important is the availability of accountability. Once mutual trust and obligation are established, an energetic and cooperative culture leads people to do their best.

Accountability is also the organizing principle of democracy: voters elect leaders who preside over an unbroken chain of accountability down to subordinate officials. But the links in our chain of accountability are broken. Police chiefs, school principals, and government commissioners have lost their ability to hold their personnel accountable. Over 99 percent of today’s federal employees receive a “fully successful” job rating. California has one of the country’s worst school systems but can terminate no more than two or three teachers per year for poor performance. In New York, a teacher who went to jail for selling cocaine had to be reinstated in his job after his release. Under Minneapolis’ collective bargaining agreement with its union, the city’s police chief couldn’t even reassign Derek Chauvin for past misconduct, let alone terminate him, without a legal proceeding.

Democracy can’t function effectively without accountability. The conditions for social trust disappear. One effect is widespread anger and resentment at people acting irresponsibly or demanding things they don’t deserve. Society goes into a downward spiral of cynicism and selfishness. Sometimes people take to the streets.

The Illusion of Objectivity

Most people probably support the idea of accountability; but who decides, and on what basis? Most experts and academics think the job can be defined by metrics, “key performance indicators,” or other unimpeachable criteria. The Supreme Court has embraced this idea: Thus, one dubious innovation of the 1960s rights revolution was the application of due process to public personnel decisions. “It is not burdensome to give reasons,” Justice Thurgood Marshall stated, “when reasons exist.”

But “objective” accountability leads inexorably to no accountability. Being a good cop, teacher, or coworker is more complex than can be defined by objective criteria. Focusing too much on metrics—test scores, arrests, quarterly profits—will skew behavior in ways that are typically destructive. As Jerry Muller puts it in The Tyranny of Metrics (2018), measurement is useful as a tool of human judgment but not a replacement for it.

Thus, the No Child Left Behind law held schools accountable for increases in test scores—and turned many schools into drill sheds. Some school officials, supposedly role models for our youth, were caught in organized cheating schemes. In a similar way, judging surgeons by their mortality rates led many to avoid the difficult surgeries that require the most skill. Paying corporate employees according to short-term sales or profits means they will act in ways that undermine long-term corporate health.

Successful accountability rarely involves black-and-white choices. The most important qualities of employees can’t be captured by objective criteria. Good judgment, a can-do attitude and a willingness to help others can be readily identified by co-workers but are not objectifiable.

A KIPP charter school principal described to me a teacher who looked perfect on paper and tried hard but could not succeed:

He just couldn’t relate to the students. It’s hard to put my finger on exactly why. He would blow a little hot and cold, letting one student get away with talking in class and then coming down hard on someone else who did the same thing … but the effect was that the kids started arguing back. It affected the whole school. Kids would come out of his class in a belligerent mood.… We worked with him on classroom management the summer after his first year. It usually helps, but he just didn’t have the knack. So, we had to let him go.

In The Moral Life of Schools (1993), a landmark study of the traits that distinguish effective teachers, Philip Jackson and his colleagues concluded,

Laying aside all exceptions, … there is typically a lot of truth in the judgments we make of others. And this is so even when we cannot quite put our finger on the source of our opinion. That truth, we would suggest, emerges expressively. It is given off by what a person says and does, the way a smile gives off an aura of friendliness or tears a spirit of sadness.

To complicate accountability judgments, they involve not just particular persons but the way they perform in particular settings. An effective grade-school teacher may be ineffective teaching high school. “Men are neither good nor bad,” as management expert Chester Barnard observed, “but only good or bad in this or that position.”

Today, the most important criteria for fair accountability are irrelevant because they’re not objectively provable. Some of the qualities “considered too subjective to stand up in court,” as Walter Olson notes in The Excuse Factory, include these: “temperament, habits, demeanor, bearing, manner, maturity, drive, leadership ability, personal appearance, stability, cooperativeness, dependability, adaptability, industry, work habits, attitude toward detail, and interest in the job.” How could the Minneapolis police chief prove that Derek Chauvin was too tightly wound?

The Irreducibility of Human Judgment

Reviving accountability requires coming to grips with the reality that it always requires subjective judgments, in context, about the relative performance of each employee. Since the 1960s, America has rebuilt its governing structures to eliminate human judgment as far as possible. Letting people make judgments about others leaves room for unfairness or bias. Who are you to judge? Worse, we’re told to distrust our own judgments as vulnerable to unconscious bias. How can we protect against that?

What’s needed is a new protocol that instills some level of trust in accountability judgments without getting mired in rigid rights, metrics, and near-endless legal arguments. The obvious solution is to restore the legitimacy of human judgment not only for supervisors but also for other stakeholders. Studies suggest that coworkers usually have a consensus view on who’s good and who’s not: “Everyone knows who the bad teacher is.”

A school could have a parent-teacher committee with authority to veto unfair termination decisions. A police department could have an accountability review committee comprised of police, prosecutors, and citizen representatives. Private companies like Toyota have workers’ councils that give opinions before an employee is let go.

Oversight committees are hardly infallible but can provide speed bumps against supervisory unfairness. Discriminatory practices can still be reviewed by courts or other authorities where there are credible allegations of systemic discrimination.

But the pervasive overhang of legal threats for personnel judgments must be removed. Legal proceedings asserting individual rights against accountability will be irresistible to many affected workers. Nature has wired people to self-justify, and the accountable individual, studies show, is uniquely incapable of judging the fairness of such a decision. How well anyone does in an organization, Friedrich Hayek put it, “must be determined by the opinion of other people.”

We’re trained to be reluctant to let people judge other people; we want legal proof. But putting personnel judgments through the legal grinder is even less reliable. How do you prove which person doesn’t try hard, or which teacher can’t hold students’ attention?

Journalist Steven Brill described one 45-day hearing to try to terminate a teacher who was not only inept but didn’t try. She never corrected student work, filled out report cards, or met even the most rudimentary responsibilities. Her defense? There was no proof that she had been given an instruction manual telling her to do these things. This type of sophistry is typical in due process hearings: As one union official put it, “I’m here to defend even the worst people.”

Cooking accountability in a legal cauldron is in most circumstances a recipe for bitterness and frustration. The personal disappointment of a job not working out, which would be quickly forgotten if the person got a new job, becomes a kind of holy war, consuming the life of the individual supposedly protected. Discrimination lawsuits are notorious for both their high emotions and their low success rate. A federal judge told me about a case in which the evidence was overwhelming that the employee was not up to the job—but the worker was in tears at the injustice done to him.

Honoring Everyone Else’s Rights

No human grouping can long survive if its members flout accepted norms of right and wrong or tolerate failure as normal.

The quest to make accountability a matter of objective proof has turned out to be a blind alley, leading inexorably to unaccountability. No one should have the right to be unaccountable. Any claim of superior rights violates everyone else’s rights. Rights are supposed to protect against unlawful coercion, not against the judgments of other free citizens or the choices needed to manage an institution.

Putting the magnifying glass on the accountable individual ignores the rights of other affected individuals. What about the unfairness to coworkers and the public of having to deal with an uncooperative or inept person? For institutions, removing accountability is like pouring acid over workplace culture. The 2003 Volcker Commission on the federal civil service found deep resentment at “the protections provided to those poor performers” who “impede their own work and drag down the reputation of all government workers.” That’s why America’s public culture too often lacks energy, pride, and effectiveness.

Democracy fails when public institutions can’t do their jobs properly. As demonstrated by abusive cops and inept teachers, viewing accountability as a matter of individual rights means that police, schools, and other social institutions can’t serve the public effectively. Democracy becomes vestigial, a process of electing figureheads who have little effective authority over the way government operates.

In all these ways and more, the loss of accountability has eroded the rights and freedoms of all Americans, compromising much of what is admirable and strong in American culture. Good government is impossible unless officials have room to use their common sense, but no one will trust officials without clear lines of accountability.

Like putting a plug back in a socket, restoring accountability will reenergize human initiative in government and throughout society. Most people want the freedom and self-respect of doing things in their own ways and the camaraderie of working with others who also value human initiative. But the freedom to take initiative has one condition: accountability. Individuals cannot be immune from the judgments of others without undermining freedom itself.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based civic leader, author, lawyer and photographer, is founder of Common Good (commongood.org) and author, most recently, of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left (2019). This essay first appeared in American Purpose

Sense of powerlessness leads to political insanity in America

Rioters in the Capitol on Jan. 6

The most compelling political statements today are those that focus on mutual respect and factual truth — such as this statement<https://simplifygov.us13.list-manage.com/track/click?u=9df171ae6d6b7a01570236616&id=74cae9b3ca&e=f8aee0dd0d by Republican Mayor David Holt, of Oklahoma City, just two days before the mob attacked the Capitol, or the victory statement https://simplifygov.us13.list-manage.com/track/click?u=9df171ae6d6b7a01570236616&id=e43c382fe9&e=f8aee0dd0d>t<https://simplifygov.us13.list-manage.com/track/click?u=9df171ae6d6b7a01570236616&id=e4f09d32e3&e=f8aee0dd0d by Georgia Democratic Sen.-elect Raphael Warnock.

But why does such a large group of Americans feel so alienated that they abandon basic civilized values? One of the main reasons, I think, is a sense of powerlessness. They're stretched thin, due to economic forces beyond their control. They don't think that their views matter, or that they can make a difference in, say, their schools or communities. They can't even be themselves. Spontaneity, which philosopher Hannah Arendt considered "the most elementary manifestation of human freedom," is fraught with legal peril: "Can I prove what I'm about to say or do is legally correct?"

The cure requires reviving human responsibility at all levels of authority. People need to feel free to roll up their sleeves and get things done. They need to feel free to be themselves in daily interactions, accountable for their overall character and competence. A functioning democracy requires officials to take responsibility for results, not mindless compliance. In an essay published this week by Yale Law Journal, "From Progressivism to Paralysis’’ https://simplifygov.us13.list-manage.com/track/click?u=9df171ae6d6b7a01570236616&id=9b9303c0e3&e=f8aee0dd0d>," I describe how good government slowly evolved into a framework that disempowers everyone, even the president, from acting sensibly.

The sluggish rollout of COVID-19 vaccines is only the latest manifestation of a micromanagement governing philosophy that suffocates leadership as well as disempowering citizens.

It's time to reboot the system, not to deregulate but re-regulate in a way that revives the American can-do spirit at all levels of society. This requires a new movement. If you agree, please contact phoward@commongood.org.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, civic and cultural leader, legal and regulatory reformer and photographer, is founder and chairman of Common Good (commongood.org). He’s the author of The Death of Common Sense, The Collapse of the Common Good, Life Without Lawyers, The Rule of Nobody and Try Common Sense.

America the Dizzy in 2020

On a launch in New York Harbor

— Photo by Philip K. Howard, New York-based photographer, civic reformer, lawyer, arts leader and author.

See:

https://philipkhoward.com/

Philip K. Howard: Principles to unify America

The Great Seal of the United States. The Latin means “Out of Many, One’’

“America is deeply divided”: That’s the post-mortem wisdom from this year’s election.

Surveys repeatedly show, however, that most Americans share the same core values and goals, such as responsibility, accountability and fairness. One issue that enjoys overwhelming popular support is the need to fix broken government. Two-thirds of Americans in a 2019 University of Chicago/AP poll agreed that government requires “major structural changes.”

President-elect Biden has a unique opportunity to bring Americans together by focusing on making government work better. Extremism is an understandable response to the almost perfect record of public failures in recent years. The botched response to COVID-19, and continued confusion over imposing a mask mandate, are just the latest symptoms of a bureaucratic megalith that can’t get out of its own way. Almost a third of the health-care dollar goes to red tape. The United States is 55th in World Bank rankings for ease of starting a business. The human toll of all this red tape is reflected in the epidemic of burnout in hospitals, schools, and government itself.

More than anything, Washington needs a spring cleaning. Officials and citizens must have room to ask: “What’s the right thing to do here?” If we want schools and hospitals to work, and for permits to be given in months instead of years, Americans at every level of responsibility must be liberated to use their common sense. Accountability, not suffocating legal dictates, should be our protection against bad choices.

But there’s a reason why neither party presented a reform vision: It can’t be done without cleaning out codes that are clogged with interest-group favors. Changing how government works is literally inconceivable to most political insiders. I remember the knowing smile of then-House Speaker John Boehner’s (R.-Ohio) when I suggested a special commission to clean out obsolete laws, such as the 1920 Jones Act, which, by forbidding foreign-flag ships from transporting goods between domestic ports, can double the cost of shipping. I also remember the matter-of-fact rejection by then-Rep. Rahm Emanuel (D.-Ill.) of pilot projects for expert health courts — supported by every legitimate health-care constituency, including AARP and patient groups — when he heard that the National Trial Lawyers opposed it: “But that’s where we get our funding.”

Cleaning the stables would help everyone, but the politics of incremental reform are insurmountable. That’s why, as with closing unnecessary defense bases, the only path to success is to appoint independent commissions to propose simplified structures. Then interest groups and the public at large can evaluate the overall benefits of the new frameworks.

Over the summer, 100 leading experts and citizens, including former governors and senators from both parties, launched a Campaign for Common Good calling for spring cleaning commissions. Instead of thousand-page rulebooks, the Campaign proposed that new codes abide by core governing principles, more like the Constitution, that honor the freedom of citizens and officials alike to use their common sense:

Six Principles to Make Government Work Again

Govern for Goals. Government must focus on results, not red tape. Simplify most law into legal principles that give officials and citizens the duty of meeting goals, and the flexibility to allow them to use their common sense.

Honor Human Responsibility. Nothing works unless a person makes it work. Bureaucracy fails because it suffocates human initiative with central dictates. Give us back the freedom to make a difference.

Everyone is Accountable. Accountability is the currency of a free society. Officials must be accountable for results. Unless there’s accountability all around, everyone will soon find themselves tangled in red tape.

Reboot Regulation. Too few government programs work as intended. Many are obsolete. Most squander public and private resources with bureaucratic micromanagement. Rebooting old programs will release vast resources for current needs such as the pandemic, infrastructure, climate change, and income stagnation.

Return Government to the People. Responsibility works for communities as well as individuals. Give localities and local organizations more ownership and control of social services, including, especially, for schools and issues such as homelessness.

Restore the Moral Basis of Public Choices. Public trust is essential to a healthy culture. This requires officials to adhere to basic moral values — especially truthfulness, the golden rule, and stewardship for the future. All laws, programs and rights mist be justified for the common good. No one should have rights superior to anyone else.

Is America divided? Many of the problems that caused people to take to the streets this year reflect the inability of officials to act on these principles. The cop involved in the killing of George Floyd should have been taken off the streets years ago — but union rules made accountability impossible. The delay in responding to COVID was caused in part by ridiculous red tape. The inability to build fire breaks on the west coast was caused by procedures that disempowered forestry officials.

The enemy is not each other, as President-elect Biden has repeatedly said. The enemy is the Washington status quo — a ruinously expensive and paralytic bureaucratic quicksand. Change is in the air. But the politics are impossible. That’s why one of first acts of President Biden should be to appoint spring cleaning commissions to propose new frameworks that will liberate Americans at all levels of responsibility to roll up their sleeves and make America work again.

American government needs big change, but the changes could hardly be less revolutionary. Instead of attacking each other, Americans need to unite around core values of responsibility and good sense.

Philip K. Howard is founder of Campaign for Common Good. His latest book is Try Common Sense. Follow him on Twitter: @PhilipKHoward.

Mr. Howard, a lawyer, is the founder and chairman of the nonprofit legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org), a New York City-based civic and cultural leader and a photographer. This piece first ran in The Hill.

Philip K. Howard: Misdiagnosing what has led to failed state America

People want answers for what went wrong with America’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic—from lack of preparedness, to delays in containing the virus, to failing to ramp up testing capacity and the production of protective gear. But almost nowhere in the current discussion can one find a coherent vision for how to avoid the same problems next time or help restore a healthy democracy.

Bad leadership has been identified as a primary culprit. The “fish rots from the head,” as conservative columnist Matthew Purple puts it. There’s plenty to blame President Trump for, but stopping there, as, say, former New York Times critic Michiko Kakutani does, ignores many bureaucratic failures. Cass Sunstein gets closer to the mark by focusing on how red tape impedes timely choices, but even he sees the bureaucratic structures as fundamentally sound and simply in need of some culling. Sunstein suggests that “it might be acceptable or sensible to tolerate a delay” in normal times, but not in a pandemic. Tech investor Marc Andreessen sees a lack of national willpower, an unwillingness to grab hold of problems and build anew. Prominent observers such as Francis Fukuyama, George Packer and Ezra Klein blame a broken political system and a divided culture; they offer little hope for redemption, even with new leadership.

All misdiagnose what caused government to fail here, and they confuse causes with what are more likely symptoms. Fukuyama rightly identifies a critical void in American political culture: the loss of a high “degree of trust that citizens have in their government,” which countries such as Germany and South Korea enjoy. But why have Americans lost trust in their government?

No doubt, after this is all over, a report will catalog the errors and misjudgments that let COVID-19 shut down America. The report will likely begin years back, when officials refused to heed warnings about pandemic planning. It will further expose President Trump, who for almost two months said that the coronavirus was “totally under control.” Errors of judgment like these are inevitable, to some degree—they happened before and after Pearl Harbor and 9/11, too—and with luck, they will inform future planning. The light will then shine on the operating framework of modern government, revealing not mainly errors of judgment, or cultural divisions, but a tangle of red tape that causes failure. At every step, officials and public-health professionals were prevented from making vital choices by legal obstacles.

Andreessen is correct that Americans have lost the spirit to build, but that’s because we’re not allowed to build. A governing structure that takes upward of a decade to approve an infrastructure project and ranks 55th in World Bank assessments for “ease of starting a business” does not encourage individual and institutional initiative. Of course Americans don’t trust government—it gets in the way of their daily choices, even as it fails to meet many national needs.

Our response to the COVID-19 missteps should not be to wring our hands about our miserable political system, or about the cynicism and selfishness that have infected our culture. We should focus on why government fails in making daily choices. What many Americans see clearly—but most public intellectuals cannot see—is a system that prevents people from acting on their best judgment. By re-empowering officials to do what they think is right, we may also reinvigorate American culture and democracy.

The root cause of failed government is structural paralysis. What’s surprising about the tragic mishaps in dealing with COVID-19 is how unsurprising they were to the teachers, nurses and local officials who are continually stymied by bureaucratic rules. A few years ago, a tree fell into a creek in Franklin Township, N.J., and caused flooding. A town official sent a backhoe to pull it out. But then someone, probably the town lawyer, pointed out that a permit was required to remove a natural object from a “Class C-1 Creek.” It took the town almost two weeks and $12,000 in legal fees to remove the tree.

In January, University of Washington epidemiologists were hot on the trail of COVID-19. Virologist Alex Greninger had begun developing a test soon after Chinese officials published the viral genome. But while the coronavirus was in a hurry, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was not. Greninger spent 100 hours filling out an application for an FDA “emergency-use authorization” (EUA) to deploy his test in-house. He submitted the application by e-mail. Then he was told that the application was not complete until he mailed a hard copy to the FDA Document Control Center.

After a few more days, FDA officials told Greninger that they would not approve his EUA until he verified that his test did not cross-react with other viruses in his lab, and until he agreed also to test for MERS and SARS. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) then refused to release samples of SARS to Greninger because it’s too virulent. Greninger finally got samples of other viruses that satisfied the FDA. By the time they arrived, and his tests began, in early March, the outbreak was well on its way.

Regulatory tripwires continually hampered those dealing with the spreading virus. Hospitals learned that they couldn’t cope except by tossing out the rulebooks; other institutions weren’t so lucky. For example, after schools were shut down, needy students no longer had meals. Katie Wilson, executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance and a former Obama administration official, secured an agreement in principle to transfer federal meal funding to a program that provides meals during summer months. But red tape required a formal waiver from each state, which in turn required formal waivers from Washington. The bureaucratic instinct was relentless: school districts in Oregon were first required to “develop a plan as to how they are going to target the most-needy students.” Meantime, the children got no meals. New York Times columnist Bret Stephens, interviewing Wilson, summarized her plea to government: “Stop getting in the way.”

What’s needed to pull the tree out of the creek is no different than what’s needed to feed school kids: responsible people with the authority to act. They can be accountable for what they do and how well they do it, but they can’t succeed if they must continually pass through the eye of the bureaucratic needle.

Reformers are looking in the wrong direction. Electing new leaders won’t liberate Americans to take initiative. Nor is “deregulation” generally the solution for inept government; the free market won’t protect us against pandemics. The only solution is to replace the current operating system with a framework that empowers people again to take responsibility. We must reregulate, not deregulate.

American government rebuilt itself after the 1960s on the premise of avoiding human error by replacing human choice. That’s when we got the innovation of thousand-page rulebooks dictating the one-correct-way to do things. We mandated legal hearings for ordinary supervisory choices, such as maintaining order in classrooms or evaluating employees. We replaced human judgment with rules and objective proof. Finally, government would be pure—almost like a software program. Just follow the rules.

For 50 years, legislative and administrative law has piled up, causing public paralysis and private frustration. Almost no one has questioned why government prevents people from using their common sense. Conservatives misdiagnose the flaw as too much government; liberals resist any critique of public programs, assuming that any reform is a pretext for deregulation. In the recent Democratic presidential debates, no one asked how to make government work better.

Experts have it backward. Polarized politics, they say, causes public paralysis. While hyper-partisanship certainly paralyzes legislative activity, the bureaucratic idiocies that delayed everything from COVID-19 testing to school meals had nothing to do with politics. Paralysis of the public sector came first, leading to polarized politics.

By the 1990s, broad public frustration with suffocating government fueled the rise of Newt Gingrich. The growth of red tape made it hard to make anything work sensibly. Schools became anarchic; health-care bureaucracy caused costs to skyrocket; getting a permit could require a decade; and Big Brother was always hovering. Is your paperwork in order? Americans kept electing people who promised to fix it—the “Contract with America,” “Change we can believe in,” and “Drain the swamp”—but government was beyond the control of those elected to lead it. What happens when politicians give up on fixing things? They compete by pointing fingers—“It’s your fault!”—and resort to Manichean theories and identity-based villains. Public disempowerment breeds extremism.