Todd McLeish: Weasels seem to be declining in New England and elsewhere in U.S.

The Long-Tailed Weasel seems to be the most common weasel in New England.

A Long-Tailed Weasel in winter coat

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A national study of weasels from across much of the United States has revealed significant declines in all three species evaluated, which has a local biologist wondering about the status of the animals in Rhode Island.

The study by scientists in Georgia, North Carolina and New Mexico found an 87-94 percent decline in the number of least weasels, long-tailed weasels, and short-tailed weasels harvested annually by trappers over the past 60 years.

While a drop in the popularity of trapping and the low value of weasel pelts is partially to blame for the declining harvest, the researchers still detected a significant drop in the populations of all three species.

“Unless you maybe have chickens and you’re worried about a weasel eating your chickens, you probably don’t think about these species very often,” said Clemson University wildlife ecologist David Jachowski, who led the study. “Even the state agency biologists who are charged with tracking these animals really don’t have a good grasp on what is going on.”

The three weasel species are small nocturnal carnivores that feed primarily on mice, voles, shrews, and small birds, often by piercing their preys’ skull with their canine teeth. The weasels prefer dense brush and open woodland habitats, where they search for prey among stone walls, wood piles, and thickets. Because of their secretive nature and cryptic coloring, they are difficult to find and observe.

By assessing trapper data, museum collections, state statistics, a nationwide camera trapping effort, and observations reported on the internet portal iNaturalist, the scientists found the animals to be increasingly rare across most of their range.

“We have this alarming pattern across all these data sets of weasels being seen less and less,” Jachowski said. “They are most in decline at the southern edges of their ranges, especially the Southeast. Some areas like New York and the Canadian provinces can still have some dense pop ulations in localized areas.”

Jachowski noted weasel populations in southern New England are likely facing similar declines as the rest of the country. He believes, however, there is the potential for some areas of the Northeast to still have robust numbers of weasels, especially long-tailed weasels, which are considered the most common of the three species.

Charles Brown, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, who contributed data to the national study, said in his 20 years of monitoring mammal populations in the Ocean State, the only one of the three weasel species he has found is the long-tailed weasel.

“I’ve had a few infrequent encounters with them over the years and seen a few dead ones on the road,” he said. “A mammal survey done in the 1950s and early ’60s documented two short-tailed weasels, and those are the only records I’ve found for the species.”

Least weasels are not found within 300 miles of Rhode Island.

Brown has contributed 19 or 20 long-tailed weasel specimens to the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University over the years from many mainland communities, including Little Compton, East Providence, Warwick, and South Kingstown. Weasels are not known to inhabit any of the Narragansett Bay islands.

“It’s hard to say what their status is here,” he said. “Trappers might bring in one or two a year, and some years none, and we don’t have any other indexes to monitor them because they’re cryptic and we rarely see them.”

Brown said a monitoring program could be developed for weasels in the state using track surveys and camera traps, but because the animals have little economic value and do not cause significant damage, they have not been a priority to study.

“In a perfect world, I’d certainly like to try to find a specimen of a short-tailed weasel to see if they’re still around here, but I have nothing to go on about them from a historic perspective,” he said.

Data from the University of Rhode Island is helping to provide a current perspective of the species’ distribution. URI scientists recently concluded a five-year study of bobcats and the first year of a study of fishers, each using 100 trail cameras scattered throughout the state. Among the 850,000 images collected so far are about 150 photos of long-tailed weasels.

According to Amy Mayer, who is coordinating the studies, the weasel images were collected at numerous locations around the state, suggesting the population does not appear to be concentrated in any particular area of Rhode Island.

It is uncertain what could be causing the national decline in weasel numbers, though Jachowski and Brown believe the increasing use of rodenticides, which kill many weasel prey species, could be one factor. A recent study of fishers collected from remote areas of New Hampshire found the presence of rodenticides in the tissues of many of the animals.

“How it’s getting into the food chain in these remote areas, we don’t know,” Brown said. “There was some discussion that a lot of people go up there to summer camps, and when they close the camp up for the season, they bomb it with rodenticides to keep the mice out. That’s just speculation, but it makes sense.”

The decline of weasels may also have to do with changes to available habitat, the scientists said. The maturing of forests and decline of agricultural land has caused a reduction in the early successional habitats the animals prefer. Brown also believes the recovery of hawk and owl populations, which compete with weasels for mice and voles and which may occasionally kill a weasel, could also be a factor.

Jachowski said the findings from his national study have led to the formation of what he is calling a “weasel working group” to share data and discuss how to monitor the animals around the country. Brown is among the state biologists and academic researchers who are members of the group.

“We’re hoping the public will become involved, too, by reporting their sightings to iNaturalist,” Jachowski said. “We need to see where they persist, and then we can tease out what habitats they’re still in, what regions, and then do our studies to figure out what kind of management may be needed.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.e

Todd McLeish: Frozen frogs are thawing out for spring but face death on the roads

Wood frog

— Photo by Brian Gratwicke

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic a yer ago coincided with the annual migration of frogs and salamanders to their breeding ponds, a trek that often results in mass mortalities as they cross roads trying to reach their preferred waterbody. The lockdown during the early stages of the pandemic last year gave a significant reprieve to amphibian populations, reducing roadway mortalities by as much as half, according to a New England researcher.

But this year, with traffic back to near normal levels, frogs and salamanders aren’t likely to fare as well. And wood frogs will likely be at the top of the list of roadkill victims.

In southern New England, wood frogs are one of the first signs of spring, according to herpetologist Mike Cavaliere, the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s stewardship specialist. They are the first species to emerge from their winter hibernation, typically in mid to late March. And as soon as they awaken, he said, they hop to their breeding pools to seek a mate on the first night it rains.

“What’s particularly amazing about wood frogs is that they can produce a natural antifreeze that allows them to almost freeze completely solid in winter,” Cavaliere said. “This antifreeze is produced when the frogs start to feel ice crystals begin to form in late fall.”

Unique among frogs in the Northeast, the wood frog’s antifreeze is a chemical reaction between stored urine and glucose, which protects a frog’s cells and organs from freezing while allowing the rest of its body to freeze.

“Its brain shuts down, its heart stops, its lungs stop, everything stops for months. It’s like they’re in suspended animation,” Cavaliere said. “And once spring comes, they thaw out and the heart starts beating again. After about a day, they start hopping around, eating and mating right away. It’s an amazing feat of evolution that they’ve developed.”

Wood frogs are often joined by spring peepers and spotted salamanders in migrating to their breeding pools during rainy nights in March, but it’s the frogs that are killed in the greatest numbers.

“Road mortality is one of the great seemingly unassessed sources of pressure for amphibians,” said Greg LeClair, a graduate student at the University of Maine who coordinates The Big Night, an amphibian monitoring project to quantify the roadkill of frogs and salamanders during their spring migration. “We know that disease and climate are affecting amphibians, but road mortality has long been suspected to be a serious problem, though there is no data to quantify population declines.”

LeClair said that road mortality can be as high as 100 percent in some areas when traffic is high during the one night of the season that most migration takes place.

“The average is 20 percent of amphibians at any road crossing will get nailed by a car in a given year,” he said. “That’s devastating for some species.”

During The Big Night, volunteers at 300 sites around Maine typically find two living amphibians crossing the road for every one dead one. But last year, with far fewer vehicles on the road because of the pandemic, twice as many frogs and salamanders survived the journey. In fact, a study by the Road Ecology Center found that pandemic lockdowns last year spared millions of animals from roadway deaths.

“We had record survival, but we’ll never be able to replicate that data again,” said LeClair, noting the impossibility of experimentally reducing region-wide traffic levels like happened with the pandemic.

While last year’s reduction in road mortality probably resulted in a short-term increase in amphibian populations, LeClair said that doesn’t mean there will be more breeding activity this year, since it takes several years for amphibians to grow to adulthood and begin breeding.

“It will take a couple years to determine if amphibian populations benefitted from the pandemic. My suspicion is leaning toward no benefit,” he said. “Most amphibian populations are driven by juvenile survival more than adult survival, so impacts to juveniles have stronger impacts than impacts to adults. Dispersing juveniles last summer likely encountered normal-level traffic as they left the pool to find a territory.”

Whether wood frogs and other amphibians benefitted from the pandemic shutdowns, their increased survival rate last spring almost certainly benefitted other wildlife.

“Their eggs and tadpoles are a major food source for other animals in spring,” Cavaliere said. “It’s one of the first sources of protein available, so spotted turtles and other reptiles and amphibians will eat them, as will any other scavenger who’s hungry in spring and looking for protein.”

Those interested in helping scientists gather data about frog populations in Rhode Island should sign up to participate in FrogWatch through the Roger Williams Park Zoo. Online training for the program is available through March 31.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish, an ecoRI News contributor, runs a wildlife blog.

Don Pesci: Time to pivot in Connecticut

The neo-classical City Hall in Bridgeport, like all Connecticut cities heavily Democratic

— Photo by Jerry Dougherty

The Connecticut state seal. The Latin motto means “He Who Transplanted Still Sustains"

VERNON, Conn.

Optimists who believe in free markets – the opposite of which are unfree, illiberal, highly regulated markets – knew, shortly after Coronavirus slammed into the United States from Wuhan, China, that the virus and the free market were inseparably connected. The more often autocratic governors restricted the public market, the more often jobs would be lost, and the loss of jobs and entrepreneurial capital everywhere would necessarily punch holes in state budgets. In many cases, the holes were prepunched by governors and legislators who, before the Coronavirus panic, had failed to understand the direct connection between high taxes, which depletes creative capital, and sluggish economies. For the last thirty years, it has taken Connecticut ten years to recover from national recessions.

The dialectic of getting and spending is a matter of simple observation and logic: the more governments get in taxes, the more they spend; the more they spend, the greater the need for taxation. Excessive spending – more properly, the indisposition to cut spending – takes a toll on capital formation and use, which leads to business flight and all its attendant evils, such as high unemployment, entrepreneurial stagnation and lingering recessions.

There would come a time, post-Coronavirus, free-market optimists thought, when states would begin to pivot from artificially constricting the economy by means of gubernatorial emergency power declarations to a much desired return to organic normalcy. That pivot already has been put in motion by governors in many conservative woke states.

The entire Northeast has for many years been the victim of the past successes of Democrat politics, which involves harvesting votes by buying them, usually by dispensing tax dollars and power-sharing to reliable political constituencies. Large cities in Connecticut – Hartford, Bridgeport, New Haven, have been held captive by Democrats for nearly a half century. During the last few elections – President Donald Trump’s 2016 election, disappointing to Clintonistas, being the most conspicuous exception to the rule – Democrats have been able to cobble together epicentric majorities in most power centers in the Northeast, relying upon large cities to carry them over the election goal line. This strategy has had, until now, little to do with political ideology and a great deal to do with campaign acumen and a leftward lurch on social issues long abandoned by Connecticut Republicans. Presence in politics has always been more important than little understood ideologies, and Connecticut Republicans have been absent without leave on social issues for decades.

Over time, Democrats, by focusing on social issues, have managed to move what used to be called the “vital center” in national politics much further to the left. And this ideological shift has hurt 1) Republicans who seem unable or unwilling to gain a foothold on important social issues, 2) liberal “{John} Kennedy” Democrats now caught in political limbo following a recent neo-progressive upsurge, and 3) disadvantaged groups, once the mainstay of liberal politics in the ‘”Camelot” era of President Kennedy, now frozen politically and socially in empathy cement, finding no way forward into what once had been a robust middle class.

There is no question, even among progressives who wish to move money from privileged, disappointingly white millionaires to despairing non-white urban voters, that a vibrant economy lifts all the boats. The distribution of zero dollars is zero, and there simply is not enough money in the bulging bank accounts of Connecticut’s millionaires to finance the state’s welfare system for more than a few years – even if it were possible for eat-the-millionaires, white, privileged, neo-progressives to expropriate all the surplus riches of Connecticut’s “Gold Coast” millionaires and send the dispossessed to work in re-education farms in West Hartford. No middle class tide, no lift. Yesterday, today and tomorrow, it will be Connecticut’s dwindling middle class that will carry the “privileged” white man’s burden.

Like other governors in the Northeast, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont, who stumbled into Nutmeg State politics without much political experience, has become, thanks to Coronavirus and the inveterate cowardice of legislators, a plenary governor the likes of which the Republic has not seen since American patriots – the word “patriot” was first used as a reproach against benighted revolutionaries by monarchists – chased agents of King George III out of their country.

Both Lamont and his friend New York Gov Andrew Cuomo have worn their plenary powers well, but the Coronavirus scourge is receding, and Cuomo has “slipped in blood.” Worst of all, representative government in some states appears to be making a comeback, and people are beginning to resent facemasks and gubernatorial edits as signs and symbols of their own powerless assent to a very un-republican subservience.

Politicians across the state and nation would be wise to step in front of a populist republican reformation before they are carted off in revolutionary tumbrils.

Pivot now. Later will be too late.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Researchers study effects of warming water on lobsters, sea scallops off Northeast

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Researchers have projected significant changes in the habitat of commercially important American lobster and sea scallops along the continental shelf off the Northeast. They used a suite of models to estimate how species will react as waters warm. The researchers suggest that American lobster will move further offshore and sea scallops will shift to the north in the coming decades.

The study’s findings were published recently in Diversity and Distributions. They pose fishery management challenges as the changes can move stocks into and out of fixed management areas. Habitats within current management areas will also experience changes — some will show species increases, others decreases, and others will experience no change.

“Changes in stock distribution affect where fish and shellfish can be caught and who has access to them over time,” said Vincent Saba, a fishery biologist in the Ecosystems Dynamics and Assessment Branch at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a co-author of the study. “American lobster and sea scallop are two of the most economically valuable single-species fisheries in the entire United States. They are also important to the economic and cultural well-being of coastal communities in the Northeast. Any changes to their distribution and abundance will have major impacts.”

Saba and colleagues used a group of species distribution models and a high-resolution global climate model. They projected the possible impact of climate change on suitable habitat for the two species in the large Northeast continental shelf marine ecosystem. This ecosystem includes waters of the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank, the Mid-Atlantic Bight, and southern New England.

The high-resolution global climate model generated projections of future ocean bottom temperatures and salinity conditions across the ecosystem, and identified where suitable habitat would occur for the two species.

To reduce bias and uncertainty in the model projections, the team used nearshore and offshore fisheries independent trawl survey data to train the habitat models. Those data were collected on multiple surveys over a wide geographic area from 1984 to 2016. The model combined this information with historical temperature and salinity data. It also incorporated 80 years of projected bottom temperature and salinity changes in response to a high greenhouse-gas emissions scenario. That scenario has an annual 1 percent increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

American lobsters are large, mobile animals that migrate to find optimal biological and physical conditions. Sea scallops are bivalve mollusks that are largely sedentary, especially during their adult phase. Both species are affected by changes in water temperature, salinity, ocean currents, and other oceanographic conditions.

Projected warming during the next 80 years showed deep areas in the Gulf of Maine becoming increasingly suitable lobster habitat. During the spring, western Long Island Sound and the area south of Rhode Island in the southern New England region showed habitat suitability. That suitability decreased in the fall. Warmer water in these southern areas has led to a significant decline in the lobster fishery in recent decades, according to NOAA Fisheries.

Sea-scallop distribution showed a clear northerly trend, with declining habitat suitability in the Mid-Atlantic Bight, southern New England, and Georges Bank areas.

“This study suggests that ocean warming due to climate change will act as a likely stressor to the ecosystem’s southern lobster and sea scallop fisheries and continues to drive further contraction of sea scallop and lobster habitats into the northern areas,” Saba said. “Our study only looked at ocean temperature and salinity, but other factors such as ocean acidification and changes in predation can also impact these species.”

Don Pesci: Those gubernatorial Caligulas

Decisive executive: A marble bust of Caligula restored to its original colors, identified from particles trapped in the marble

VERNON, Conn.

Gore Vidal – deceased, but not from Coronavirus complications – was once asked whether he thought the Kennedy brood had exercised extraordinary sway over Massachusetts. He did. And what did he think of the seemingly unending reign of “Lion of the Senate” Edward Kennedy, who had spent almost 43 years in office?

Vidal said he didn’t mind, because every state should have in it at least one Caligula.

The half-mad Roman emperor Caligula, who reigned in 37-41 A.D., considered himself a god, and the senators of Rome generally deferred, on pain of displeasure, to His Royal Deity. Caligula certainly acted like a god. The tribunes of the people deferred to his borderless power, which he wielded like a whip. They deferred, and deferred, and deferred… .Over time, their republic slipped through their fingers like water. Scholars think Caligula may have been murdered by a palace guard he had insulted.

Here in the United States, we do not dispose of our godlike saviors in a like manner. At worse, we may promote them to a judgeship, or they may be recruited after public service by deep-pocket lobbyists or legal firms, or they may remain in office until, as in Edward Kennedy’s case, they have shucked off their mortal coil and trouble us no longer

.Coronavirus has produced a slew of Vidal Caligulas, all of them governors. In emergencies, when chief executives are festooned with extraordinary powers, the legislature is expected to defer to the executive, and the judiciary remains quiescent.

This deference to an all-powerful executive department is not uncommon in war, but even in war, the legislative and judiciary departments remain active and viral concerning their oversight constitutional responsibilities.The war on Coronavirus, however, is a war like no other. Here in Connecticut, the General Assembly remains in a state of suspended animation. Every so often, an annoying constitutional Cassandra will pop up to remind us that we are a constitutional republic, but constitutional antibodies in Connecticut are lacking. Our constitutions, federal and state, are still the law of the land, and even our homegrown Caligulas are not “above the law,” because we are “a nation of laws, not of men.”

These expressions are more than antiquated apothegms; they are flags of liberty that, most recently, have been waved under President Trump’s nose. However, in our present Coronavirus circumstances, no one pays much attention to constitutional Cassandras because --- do you want to die? Really, DO YOU WANT TO DIE?Every soldier who has ever entered the service of his country in a war has asked himself the very same question. And we are in a Coronavirus War, are we not? Pray it may not last as long as “The War on Drugs.” Drug dealers won that one, and Connecticut has long since entered into the gambling racket; the marijuana racket looms in our future.

Then too, in the long run, we are all dead. Even “lions of the Senate” die. The whole point of life is to live honorably. And this rather high-falutin notion of honor means what your mama said it meant: don’t cheat; don’t lie; treat others as you expect them to treat you. Bathe every day and night in modesty, and remember – as astonishing as it may seem -- sometimes your moral enemy may be right. Put on your best manners in company. “The problem with bad manners,” William F. Buckley Jr. once said, “is that they sometimes lead to murder.” Caligula forgot that admonition.

Once Coronavirus has passed, we will be able honestly and forthrightly to examine closely the following propositions, many of which seem to be supported by what little, obscure data we now have at our disposal: that death projections have been wildly exaggerated; that reports of overwhelmed hospitals were exaggerated; that death counts were likely inflated; that the real death rate is magnitudes lower than it appears; that there have been under-serviced at-risk groups affected by Coronavirus; that it is not entirely clear how well isolation works; that ventilators in some cases could be causing deaths. These are open questions because insufficient data at our disposal at the moment does not permit a “scientific” answer to the questions that torment all of us.

At some point, a vaccine will be produced that will help to quiet our sometimes irrational fears, but vaccine production lies months ahead. The question before us now is: what is more dangerous, the wolf or the lion? New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, and allied governors in his Northeast compact, cannot pinpoint a date to end their destructive business shutdown because of insufficient data. According to some reports, Cuomo has hired China-connected McKinsey & Company to produce “models on testing, infections and other key data points that will underpin decisions on how and when to reopen the region’s economy.”

If the economy in Connecticut collapses because Gov. Ned Lamont accedes to the demands of those in his newly formed consortium of Northeast governors that business destroying restrictions should remain in place for months until a vaccine is widely distributed, the effects of the resulting economic implosion will certainly be more severe than a waning Coronavirus infestation. After Connecticut has reached the apex of the Coronavirus bell curve, it is altogether possible that a continuation of the cure – a severe business shutdown occasioned by policies rooted in insufficient data – will be far worse than the disease it purports to cure.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Always leaving the Northeast

An unofficial flag of New England.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Every once and while a story comes out about people leaving the Northeast, especially to move south, for jobs, lower taxes, cheaper housing, less winter and so on. These stories have been a staple of journalism since the invention of air-conditioning, which made manufacturing and its jobs more attractive in the South. And yet the Northeast remains the richest part of the country. That’s because it has the academic institutions, dense centers of skilled workers and several “world cities’ that are so closely associated with wealth creation and preservation. And it’s on the coast.

The large number of affluent people in the Northeast helps explain why property prices and taxes are so high here: They can bid up prices.

As for Northeast’s weather: Yes winter in the region can be tedious, but most of the year is fairly mild and the region rarely suffers the floods and droughts so frequent in much of the rest of the country. And we have plenty of fresh water. It’s interesting, by the way, that the happiest place in the world appears to be cold, dark Scandinavia, at least in part because of its public services. (Still, I think I’ll nip down to Florida for a week soon to break up the winter.…)

And there’s what should be an obvious reason why population growth in the Northeast is so slow – the region has long been densely populated and urbanized; it’s much further along in development than most of the Sunbelt. Consider that the seven most densely populated states are, in order of density: New Jersey, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware and New York (even with the vast Adirondack wilderness). They aren’t going to empty out as people move to Florida and Texas subdivisions.

The most serious demographic challenge facing the Northeast is its aging population. This is an especially serious problem for Rhode Island, exacerbated by its deeply entrenched cynicism and parochialism; someone once called it an “urban backwater.’’ It needs a higher percentage of younger adults to start and grow businesses and to help pay the soaring social costs of the elderly. More on that to come in future columns.

I’m sure that cheaper land and lower taxes (except for regressive sales taxes, which tend to be highest in the Sunbelt) will continue to draw many from the Northeast for some years to come. But I’m just as sure that the Northeast will remain the richest part of the country. And many of those who stay will appreciate its slow population growth, which means less sprawling development, and a healthier natural environment, than in much of the country. And eventually, growing populations and other demographic change will lead to political pressures for more and better public services, more controls on land development and higher taxes in the Sunbelt – even as the effects of global warming make them more problematic.

Red States/Blue States: Taxes and poverty

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

President Trump and congressional Republicans have floated the idea of eliminating the deductibility of state and local taxes on federal personal-income-tax forms. (That would hit upper-middle-class people in southern New England hard.) Not coincidentally this would most affect affluent Blue States, most importantly New York and California, which have high taxes and extensive public services. It’s all part of a much broader plan to slash taxes for Trump and other very rich people, especially those who, like the president, have non-publicly traded companies that take in “pass-through’’ income that goes directly to the owners.

Because evenhuge blue New York and California have GOP congresspeople and they would join their Democratic colleagues in fighting for that deductibility, it seems at the moment that the changewon’t be made.

In any case, the issue reminds me of the gross differences in tax policies between the states. The Red States tend to have lousy public services, high poverty, no or low state income taxes but high sales taxes, which are regressive – they disproportionately hit the middle class and the poor.

Red States tend to disproportionately represent the interest of rich people and big business, who, of course, like most of us, seek to pay as little in taxes as possible. These interests have relatively more power in Red State legislatures and governorships than in Blue States, whose citizens tend to demand stronger state government roles in education, social services, the environment and some other sectors, and thus tolerate higher taxes.

And these better public services pay off: Blue States remain as a group much richer than Red States and with better metrics on health, education, poverty, environment and physical infrastructure, including water and transportation. Indeed, one of the surprises, perhaps, over the last few decades is how the politically powerful (they control the legislative, executive and (mostly) the judicial branches) Red States still lag way behind the Northeast, with its hefty income taxes (except New Hampshire), in so many socio-economic ways.

The fact is that most people are still better off in the Northeast, even as they complain about our taxes. And the two greatestentrepreneurial, innovation and invention centers in America are Silicon Valley, in high-tax California, the Boston-Cambridge-Route 128 complex in high-tax Massachusetts, and the great wealth creator of very-high-tax, high-public-service New York City.

The worst poverty in America remains in the most Red States, and their tax systems, geared to the personalinterests of plutocrats such as the Koch Brothers, helps explain why.

Of course many well-off retirees will move to Florida from the Northeast for the weather and to avoid income taxes. They no longer need good schools for their children, who have long since grown. Then when get really old, many move back to be taken care of by their children and take advantage of social services, such as mass transit, that are lacking in Florida (which I suppose might be more precisely called a Purple State).

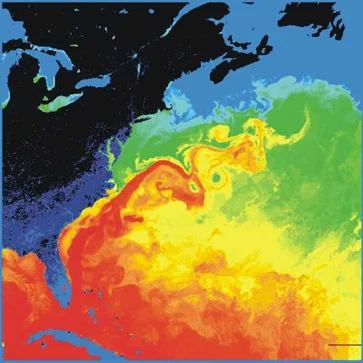

Why sea-level rise is highest here

Surface temperatures in the western North Atlantic. The North American landmass is black and dark blue (cold), while the Gulf Stream is red (warm). Source: NASA

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Why is the Northeast experiencing higher levels of sea-level rise than other parts of the wold? Area scientists attribute it to two factors: a slowdown in the Gulf Stream and the melting of ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland.

The slowdown of the Gulf Stream is complicated, and conclusions for the cause have varied. The consensus cause is the warming of the North Atlantic. What is still being debated is the effect of the influx of fresh water. Nevertheless, the warming water is creating a “traffic-jam scenario” in ocean circulation. The slowdown causes offshore sea levels, which are higher than coastal sea levels, to flatten and send water inland to regions such as the Northeast.

“Picture a banked turn in a racetrack,” said Bryan Oakley, assistant professor of environmental geoscience at Eastern Connecticut State University. “As the circulation slows, this causes the slope to decrease, and as the water level goes down along the Gulf Stream, the water level will rise along the coast — two ends of a seesaw, so to speak.”

Melting ice is also pushing water our way. As ice sheets in Greenland liquefy, they lose their gravitational pull and, therefore, ocean water that was drawn to the icy masses instead flows into the southern hemisphere. The same phenomenon is happening as the Antarctic losses ice, this time the water is redirected toward the Northeast.

There is yet another cause of higher regional waters. John King, professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island’s School of Oceanography, said warming water in the North Atlantic may halt or slow the natural cool-water vacuum that draws warmer coastal water out to sea.

All of these factors have led the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to project a maximum sea-level rise of 11.5 feet by 2100.

“Currently, about 6 million Americans live within about six feet of the sea level, and they are potentially vulnerable to permanent flooding in this century,” said Robert E. Kopp, an associate professor at Rutgers University’s Department of Earth and Planetary Science, who co-authored the recent NOAA report. “Considering possible levels of sea-level rise and their consequences is crucial to risk management.”

Those consequences to natural habitats include increased beach and marsh erosion.

In Rhode Island, there are about 7,000 people living within the 7-foot sea level-rise inundation zone, according to a Statewide Planning report.

Cyberterrorism: Will Russia, China and/or ISIS turn off our electrical power?

We just got this press release about an important conference on Newport.

Two of the best-known publishers of energy newsletters, Sam Spencer, who publishes Smart Grid Today and Power Markets Today and Llewellyn King, who founded The Energy Daily and produces and hosts White House Chronicle, on PBS, are teaming up with the Pell Center at Salve Regina University on a comprehensive conference on cybersecurity in the utility industry.

“Grid cybersecurity is one of the critical frontiers in the security of the U.S. infrastructure system,” King said.

The conference will be held Sept. 26-29, 2016 at Salve Regina University in Newport. “In this scholarly setting the industry can learn best practices; cybersecurity vendors and others can get down to granular issues that aren’t easily discussed in the office setting,” Spencer said.

The “Newport Conference” will bring together utility IT officers, managers, first responder teams as well as vendors of firewalls, alarms and other security systems for utilities.

“The utility industry is undergoing great changes in its structure. It is being reshaped by disruptive technologies, environmental pressures and social expectations.

“More and more, the old grid is giving way to the new grid in a sophisticated, computer-dominated world where the enemy could be in any line of code, any weak link in the industry,” Spencer said.

King added: “The first goal of modern warfare is to take out the electrical supply, and the rest follows from there. As a result, those who wish to do harm to a country — and to the United States, in particular — are aware that without electricity, a great nation is paralyzed.”

He said that he saw the precursor to this kind of havoc back in 1965, when most of the Northeast went dark. That was incredible but today, with more reliance on electricity throughout the life of the nation, things would be even worse.

King and Spencer said enemies, both state and non-state (like ISIS), are hard at work probing our cyber-defenses, seeking weakness and waiting to strike.

“We want to advance the understanding of the threat as well as to ensure that the best practices in cybersecurity are being followed as the grid itself changes into something new and even more electronically interconnected than in the past,” they said.

For sponsorship and registration information, please contact Llewellyn King at 1-202-662-9731 or 1-202-441-2702, or e-mail him at llewellynking1@gmail.com.

Robert Whitcomb: Too much wind for too much wood on Sept. 21, 1938

“The roaring wind toppled forests in every New England state, with New Hampshire and Massachusetts (east of the eye of the storm) hit particularly hard. The path of destruction spanned ninety miles across....’’ And “70 percent or more of the toppled timber was Pinus strobus – eastern white pine’’ – the most valuable (and vulnerable) tree crop in New England because of its height, straightness and its many uses, from lumber to make houses, to furniture to cheap shipping boxe

(Original review published by The Weekly Standard)

When I was a boy living in coastal Massachusetts I frequently heard stories about the great hurricane that crashed into Long Island and New England on Sept. 21, 1938. Most of the people who described it to me – my father and some of his friends -- were only in their thirties and early forties when they told me about it, and had very vivid stories, especially after a few drinks."

What the 1906 earthquake is to San Francisco, the 1871 fire is to Chicago and Hurricane Katrina is to New Orleans, the ’38 Hurricane (aka “The Long Island Express’’) is to New England and Long Island.

Given the scale of the catastrophe in one of the most populous and richest parts of the country, the ’38 Hurricane at first got surprisingly little attention from the rest of the country because attention was riveted on the Munich Crisis; many assumed that war was about to break out in Europe; of course, that wouldn’t be for another year.

The storm killed around 700 people and destroyed many buildings, bridges and miles of road. Its tidal surge altered long stretches of the southern New England and Long Island coasts.

Stephen Long clearly and dramatically, and sometimes with droll humor, details the mayhem produced by torrential rain followed by winds that gusted to nearly 200 miles an hour on Blue Hill, south of Boston. He serves up a mix of regional history, meteorology, botany, ecology, politics, economics -- allseasoned with anecdotes.

But his book is mostly about the trees that the storm took down, especially in New England’s large and well-established second-growth forests and “the pastoral combination of farm field and forest {that} adorned’’ the region, interspersed by villages with steepled white churches. That’s the (unrepresentative) scene that many tourists most associate with the region. The storm’s massive blowdowns (including of steeples) altered the views in many places.

As a boy, I saw evidence of this damage in the woods next to our house, where there were numerous pits where the roots of uprooted trees had been. From the pits’ shape you could tell which direction the strongest wind came – southeast, at more than 100 miles an hour. And there were still many gaps in the woods where tall trees had once stood.

Mr. Long, founder and former editor of Northern Woodlands magazine, focuses on the ecological, economic and sociological effects of the storm’s destruction of mature trees in a wide swath of New England.

“The roaring wind toppled forests in every New England state, with New Hampshire and Massachusetts (east of the eye of the storm) hit particularly hard. The path of destruction spanned ninety miles across....’’ And “70 percent or more of the toppled timber was Pinus strobus – eastern white pine’’ – the most valuable (and vulnerable) tree crop in New England because of its height, straightness and its many uses, from lumber to make houses, to furniture to cheap shipping boxes. (Mr. Long describes how mighty New England’s cheap-pine-box industry was before heavy-duty cardboard and plastic took its place.)

All this devastated many landowners, already brought low by the Great Depression, who depended on pine sales from their wood lots to make ends meet.

Also torn up were many maple-tree stands, the sap from which provided a lot of extra income to New England farmers and other landowners.

Mr. Long writes very accessibly about why certain trees sustained far more damage than others -- e.g., “The taller the tree the longer the lever and the greater the force it can exert on the ground where it’s anchored.’’ Trees on southeast-facing slopes were particularly vulnerable.

Enter the New Deal, in an example of what perhaps only government can do: Clean up damage from natural disasters that extends over many square miles. Much praise was due the U.S. Forest Service, as well as Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, in responding to a disaster as huge as the ’38 Hurricane.

The first imperative, state and federal officials and an anxious public thought, was to reduce the chances of massive forest fires from the downed and thus drying trees and branches. Indeed, some of the forests were closed to the public for long stretches after the hurricane for fear of fire. That the hurricane had made many of the fire-watch towers inaccessible -- roads were blocked by fallen trees – made it that much scarier.

And so, Mr. Long explains, federal officials, led by the U.S. Forest Service, pulled together the resources of various organizations but especially thousands of otherwise unemployed men working for the CCC (young men) and the WPA (which had older men too). They opened roads and helped clean out much of the combustible debris left on the ground by the hurricane.

The Roosevelt administration pushed the project. Mr. Long describes “the WPA’s own portrayal of its hurricane relief efforts, as seen in an eleven-minute film….Shock Troops of Disaster bears a striking resemblance to wartime newsreels, depicting feverish activity accompanied by charged music and stentorian narration. Referring to the WPA, the narrator described it in this way: ‘Manpower, turning from regular public improvements and services into the breach in times of dire need.’’’

But what to do with the fallen timber taken out of the woods, which could flood the market and lower the already low price of the wood? To address this issue, the government invaded the private market with a vengeance.

Mr. Long explains: “The Forest Service saw the need for a stabilizing influence on the price of logs and the flow of lumber to the market….{so it} put the power of the federal government to work’’ by establishing “a fair price for logs,’’ and buying up all it could and then gradually selling it as “demand required. At the heart of this reasoning was that the purchasing program would allow thousands of local landowners to realize a decent return from what could have been a nearly total economic loss.’’

“The total cost of the salvage program was $16,269,000’’ {in dollars of the time}, of which 92 percent was recovered by the government. It seems doubtful that such market intervention will happen after the next big hurricane blows through. But then, FDR & Co. saw the hurricane response as another way of fighting the Depression.

The cleanup showed just how good Americans, via a collaboration of the private and public sectors, can be at addressing an emergency – as they were soon to prove after Pearl Harbor. And a lot of that hurricane wood was used in war-related products and then in the post-war building boom.

Meanwhile, with the continuing disappearance of farmland, New England is now more forested than at any time in 200 years. Some year, the Northeast will again have a record surplus of lumber on the ground after another huge hurricane. We may then long for a CCC and a WPA.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is overseer of newenglanddiary.com.

EcoRI News: Warmer water, different N.E. fish

--NOAA chart

By ecoRI News staff

See ecori.org

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists recently released the first multi-species assessment of just how vulnerable U.S. marine fish and invertebrate species are to the effects of climate change.

The study examined 82 species off the Northeast coast, where ocean warming is occurring rapidly. Researchers found that most species evaluated will be affected, and that some are likely to be more resilient to changing ocean conditions than others.

“Our method identifies specific attributes that influence marine fish and invertebrate resilience to the effects of a warming ocean and characterizes risks posed to individual species,” said Jon Hare, a fisheries oceanographer at NOAA Fisheries’ Northeast Fisheries Science Center, in Narragansett, R.I., and lead author of the study. “This work will help us better account for the effects of warming waters on our fishery species in stock assessments and when developing fishery management measures.”

The study is formally known as the “Northeast Climate Vulnerability Assessment” and is the first in a series of similar evaluations planned for fishery species in other U.S. regions. Conducting climate change-vulnerability assessments of U.S. fisheries is a priority action for NOAA.

The 82 Northeast marine species evaluated include all commercially managed fish and invertebrate species in the region, a large number of recreational fish species, all fish species listed or under consideration for listing on the federal Endangered Species Act, and a range of ecologically important species.

NOAA researchers, along with colleagues at the University of Colorado, worked together on the project. Scientists provided climate model predictions of how conditions in the region's marine environment are predicted to change in the 21st Century. The method for assessing vulnerability was adapted for marine species from similar work by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to characterize the vulnerability of wildlife species to climate change.

The method tends to categorize species that are “generalists” as less vulnerable to climate change than are those that are “specialists.” For example, Atlantic cod and yellowtail flounder are more generalists, since they can use a variety of prey and habitat, and are ranked as only moderately vulnerable to climate change.

The Atlantic sea scallop is more of a specialist, with limited mobility and high sensitivity to the ocean acidification that will be more pronounced as water temperatures warm. Thus, sea scallops have a high vulnerability ranking.

The method also evaluates the potential for shifts in distribution and stock productivity, and estimates whether climate-change effects will be more negative or more positive for a particular species.

“Vulnerability assessments provide a framework for evaluating climate impacts over a broad range of species by combining expert opinion with what we know about that species, in terms of the quantity and the quality of data,” Hare said. “This assessment helps us evaluate the relative sensitivity of a species to the effects of climate change. It does not, however, provide a way to estimate the pace, scale or magnitude of change at the species level.”

Researchers used existing information on climate and ocean conditions, species distributions and life history characteristics to estimate each species’ overall vulnerability to climate-related changes in the region. Vulnerability is defined as the risk of change in abundance or productivity resulting from climate change and variability, with relative rankings based on a combination of a species exposure to climate change and a species’ sensitivity to climate change.

Each species was evaluated and ranked in one of four vulnerability categories: low, moderate, high and very high. Animals that migrate between fresh and salt water, such as sturgeon and salmon, and those that live on the ocean bottom, such as scallops, lobsters and clams, are the most vulnerable to climate effects in the region.

Species that live nearer to the water’s surface, such as herring and mackerel, are the least vulnerable. Most species also are likely to change their distribution in response to climate change, according to the study. Numerous distribution shifts have already been documented, and the study demonstrates that widespread distribution shifts are likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Peter Baker: Illegal N.E. fishing hurts future stocks

"Outside My Window'' (Woods Hole, Mass.), copyright Bobby Baker Photography.

An aromatic site.

This article comes courtesy of ecoRI News

BOSTON

We’ve seen a rash of stories recently on illegal fishing in the Northeast, as enforcement officials take action on unreported catch. Some of the numbers are eye-popping. One bust involved 56,000 pounds of illegally caught and unreported summer flounder, also known as fluke. Another charge alleged 86,000 unreported pounds of the same fish over three years.

Research indicates that those figures are no fluke — pardon the pun. In fact, these recent incidents represent only a small fraction of illegal and unreported catch. Studies show that most illegal fishing in the region involves cheating on rules regarding the amount, type or size of fish allowed to be caught, misreporting in dealer reports, or fishing in places set aside to protect fish habitat and spawning areas. Few people realize the extent of illegal fishing, the harm it can do to ocean resources, and the ways in which this cheating undermines efforts to measure and sustainably manage fisheries.

For example, a study published in the journal Marine Policy in 2010 estimated that 12-24 percent of New England’s total catch of groundfish — bottom-dwelling fish such as cod, flounder and haddock — was taken illegally. How much fish is that? Well, when the authors took the midpoint of that estimate (18 percent) and applied it to the actual landings from the time the study was conducted, they found that the illegal catch would amount to more than 11 million pounds of fish, worth about $13 million.

And what if those illegally caught fish had instead been left in the water where they could grow and reproduce? The researchers give an estimate of that loss, too. Over five years those fish could have contributed some 65 million pounds to the overall biomass of the groundfish stock. That extra supply would be a welcome bounty today, when many groundfish populations are so low that the fishery has been declared a federal disaster, requiring tens of millions of dollars in taxpayer assistance.

Fisheries managers are responding to some problem areas. In the mid-Atlantic, for example, officials recently suspended use of a controversial “set-aside” program that had allegedly been exploited to hide catch that exceeded quotas. New England’s fishery managers have started looking into reports of vessels employing net-liners and other fishing-gear modifications that result in fish being caught under the legal size limit.

This “missing catch” from illegal fishing also complicates the work of scientists and managers who need an accurate picture of what’s really happening on the water. The actual mortality, or amount of fish killed, is a key piece of information for estimating fish populations and setting sustainable fishing levels.

The Marine Policy study found that even commercial fishermen assume that about 10 percent to 15 percent of their colleagues are routinely breaking the law. The researchers say that the odds of getting caught are slim, while the payoff from cheating is “nearly five times the economic value of expected penalties.”

All this illicit activity takes a toll on those fishermen who do follow the rules. The researchers surveyed fishermen and discovered that many believe that illegal fishing “will prevent them from ever benefiting from stock rebuilding programs.” This finding underscores one of the greatest damages. Hardworking fishermen who do the right thing as stewards of the public resource are cheated of their just reward of higher catches in the future. Although enforcement may be unpopular to some, it is critical for any well-managed fishery.

Peter Baker directs The Pew Charitable Trusts’ U.S. ocean-conservation efforts in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic.