A ‘typical American’?

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), the iconic painter and illustrator, was from the New York City area. He lived with his family in Arlington, Vt., in 1939-1953, when they moved to Stockbridge, Mass.

Rockwell said: "Without thinking too much about it, I was showing the America I knew to others who might not have noticed. My fundamental purpose is to interpret the typical American. I am a storyteller.’’

The Norman Rockwell Museum, in Stockbridge, Mass.

— Photo by Rmrfstar

Call pest control?And treating Norman Rockwell

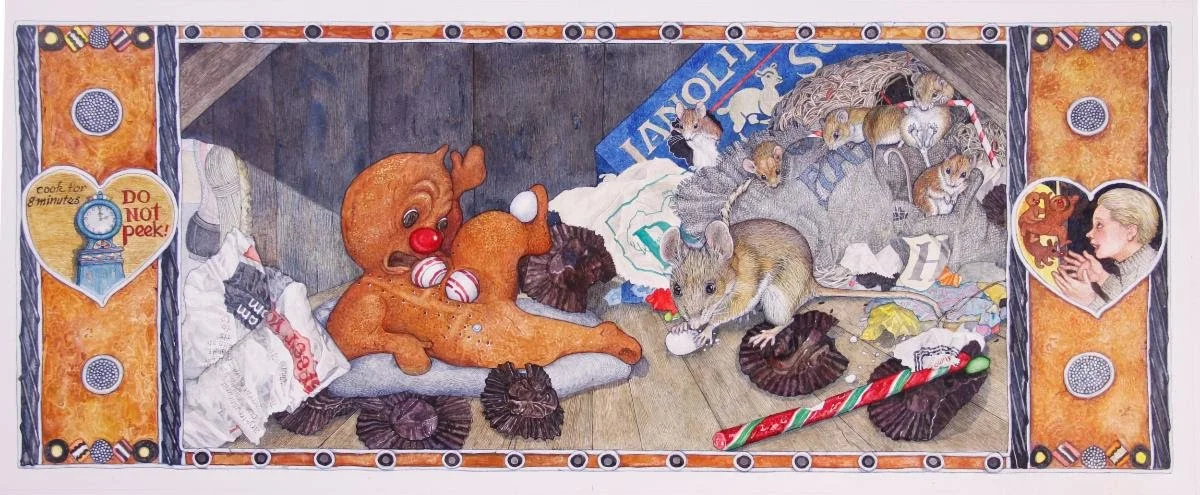

“Scritchy Scratchy,” by Jan Brett (watercolor on paper, illustration for Gingerbread Friends), in the show “Jan Brett: Stories Near and Far,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., through March 6.

Ms. Brett is the author/illustrator of such books for kids as The Mitten, Cozy and Gingerbread Baby. She has homes in the Berkshires and in Norwell, Mass., where she grew up.

The North River, with beautiful marshes, forms the southeast boundary of Norwell.

The famous Austen Riggs Center, a psychiatric institution in Stockbridge, the Berkshires town that the famed painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) moved to at least in part because of Riggs, where he and his second wife, Mary Barstow, were both treated for mental illness. His wife, the more seriously ill of the two, suffered from depression and alcoholism and Rockwell from depression and anxiety.

The very expensive Riggs had the reputation of drawing well-known patients and celebrated psychiatrists.

Rockwell once said: "I paint life as I would like it to be.’’

An old inn, Rockwell, a mental hospital and Arlo

The Red Lion inn (first part built in 1773), in Stockbridge.

“And in the quiet, rural middle of it {the Berkshires}, Stockbridge sits like nothing so much as a living postcard from small town America. Standing at dusk on Main Street, looking at the row of seasoned old storefronts, the long, classic porch of the fabled Red Lion Inn wrapping around the corner, and the tree-studded ridgeline of the Berkshires creating a green and gold and backdrop to it all, a visitor might be put in mind of a Norman Rockwell painting. Which would be perfectly apt. Rockwell lived only a block away, and he painted that very scene.’’

-- From New England Notebook, by Ted Reinsteim

He might also have noted that Stockbridge is also home to the Austen Riggs Center, a psychiatric hospital known for its celebrity patients. Its presence was a factor in Rockwell and his wife moving to the town from Arlington, Vt. Mr. and Mrs. Rockwell were both treated there for anxiety and depression. Stockbridge also hosts the Norman Rockwell Museum, which has many of the famous illustrations he did for the old Saturday Evening Post and other publications in the Golden Age of Magazines.

His Stockbridge studio was on the second floor of a row of buildings; directly underneath Rockwell's studio was, for a time in 1966, the Back Room Rest, better known as the famous "Alice's Restaurant of song and movie fame, about a bunch of '60s Hippies led (sort of!) by songwriter Arlo Guthrie and their interactions with small-town life.

The Norman Rockwell Museum.

Colorized postcard of Stockbridge made in the early 20th Century.

Rockwell and Warhol: An unlikely pairing?

Left, "Freedom from Want'' (oil on canvas), by Norman Rockwell, 1943; right, "Campbell's Soup Can'' (color silkscreen on paper) 1969, in the show "Inventing America: Rockwell and Warhol,'' at the Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., June 10-Oct. 29.

Both of these artists portrayed a kind of romanticism. Rockwell liked to say that he painted things the way he wanted life to be. But as he gotolder, he got tougher in recognizing and representing American society's flaws and the contradictions of human emotions and behavior. The nostalgia in his pictures thinned a bit.

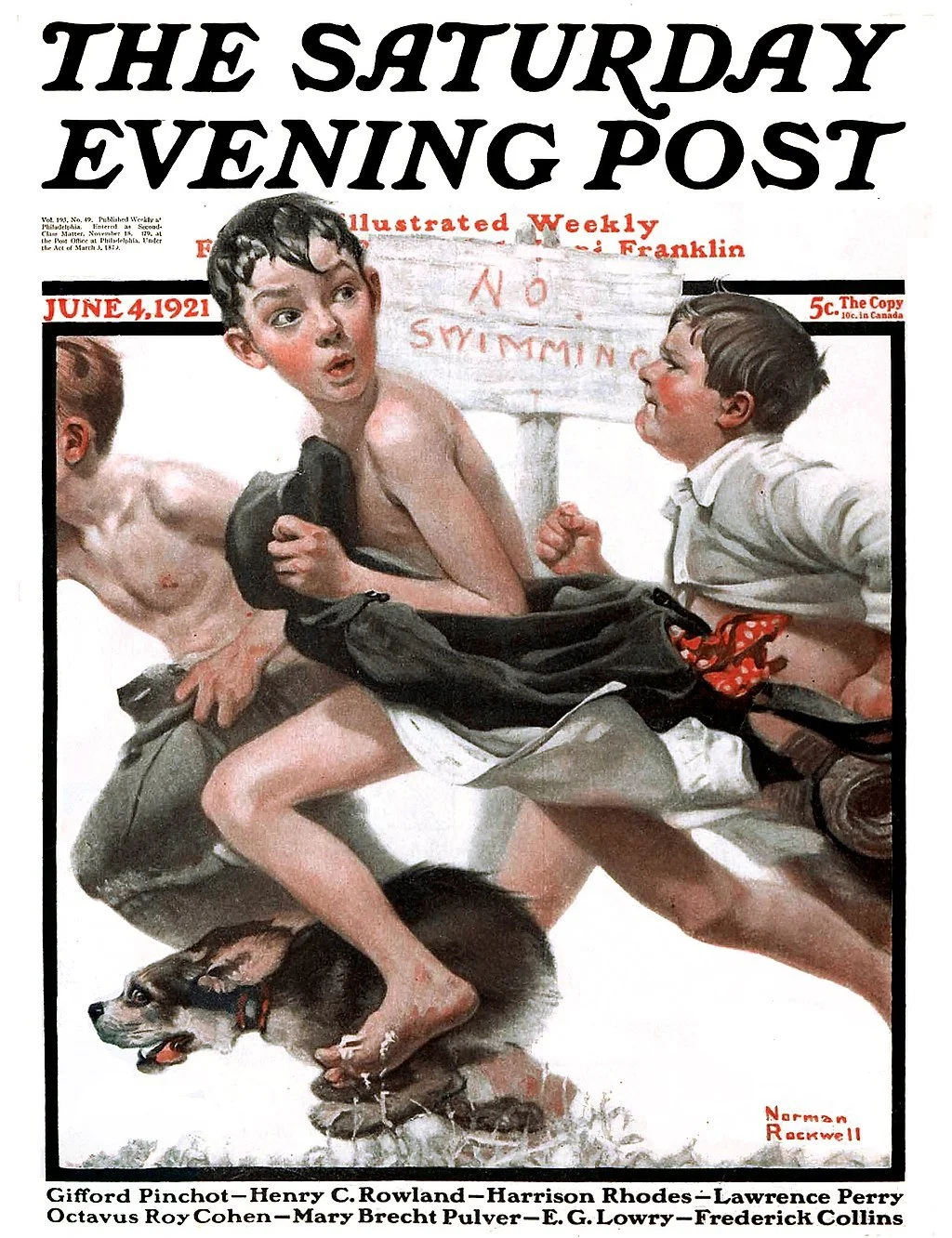

I remember with mild fondness his covers for the old Saturday Evening Post, one of about a dozen magazines we got at our house in the '50s and early '60s, before TV killed so many of them. I looked forward much more to the weekly arrival of Life magazine, with its great photos, than to the rather musty Post.

As a kid, I saw the Rockwell covers as corny. Now, in part because I know a lot more about Rockwell's sometimes troubled life, and having read many of his comments on art, his life and America, I see that his work, besides being technically superb, has far more depth than you'd see from glancing at a Post cover. By the way, one reason he and his wife moved to Stockbridge from Vermont is that Austen Riggs, the famous mental hospital is there. Mrs. Rockwell would be treated at the institution from time to time.

As for Warhol, he deeply appreciated the commercial romanticism (the passion for colorful consumer goods) and the craft of Madison Avenue's high-concept popular art during its post-World War II golden age.

When I lived in New York I saw him a couple of times from a few feet away at downtown Manhattan parties. He seemed expressionless --- cold and creepy.

Both Rockwell and Warhol presented longing --- the former for a safer and friendlier world, the latter for a world of color and humor, in which even the seemingly banal could be infused with a kind of goofy joy.

-- Robert Whitcomb

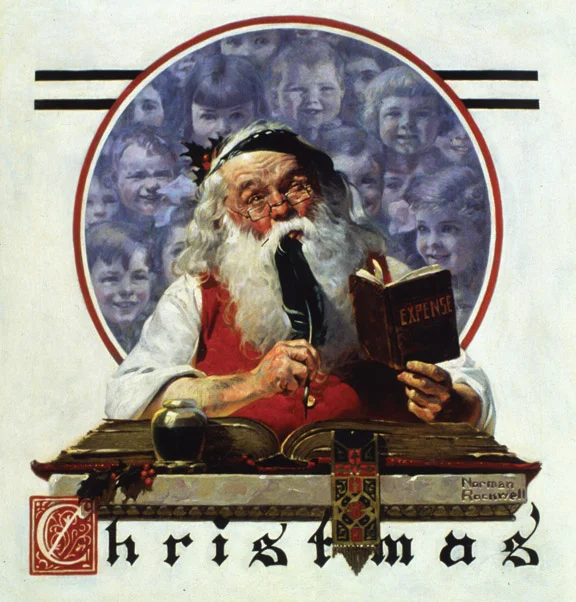

Merry Christmas from the King of Commerce

Norman Rockwell (1894–1978)

"Santa and Expense Book'' (oil on canvas), by Norman Rockwell, for the Saturday Evening Post cover of Dec. 4, 1920. This is in the collection of the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, R.I. Image courtesy of American Illustrators Gallery, NYC.

A de Tocqueville weekend in Vermont

The Bradford Congregtional Church

From Robert Whitcomb's Nov. 24 "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.

In most years for the past quarter century, I’ve joined a bunch of malefriendsand driven to Bradford, Vt., a small town on the Connecticut River, on the weekend before Thanksgiving to eat at a game supper in the Congregational (aka “Congo’’) church there. It’s held in an assembly hall beneath the nave as the church’s major annual fund-raising event. The food is a wide range of game, including beaver (yuck!), elk, venison, pheasant, wild boar, rabbit and some other animals. (Too bad they don’t offer alligator, which is quite good.)

I generally avoid meat, mostly out of sympathy for the animals and a little bit because of health. But the game dinner is for a good cause, and maybe some of the animals being served are road kill anyway.

It’s tasty enough but the trip has been mostly an excuse to get together and catch up once a year. It’s also a bit of Americannostalgia.

The small-town folks manning the supper are a delightful mix of old, young and middle aged. (Some of the teens look a bit as if they’d be drafted against their will into acting as waiters to bring the cider, coffee and dessert – always gingerbread – to the tables.)

There are always a lot of what I used to consider “old people’’ staffing the long buffet tables; I am their age now. Most of the “old people’’ we first encountered in 1990 have gone to their reward, including, I think, the blue-haired lady who used to pound out tunes from old shows such as Oklahoma! on the upright piano in the nave to amuse those waiting to be called by number to go downstairs to the chow.

There’s a big kitschy picture on the wall in that hall showing a boy Jesus teaching his elders; it must date from the late 19th Century. At least this Palestinian kid wasn’t blond, unlike in my Sunday school books in the ‘50s!

The church needs painting and I’d guess, like most mainline Protestant churches, its membership is down, so it was nice to help out a bit to keep the place going. For various reason this was my last year attending this little annual event but it’sbeen edifying to participate insuch a good-hearted community endeavor, and find out what the contemporaries in my little group were up to as they moved from middle to old age.

Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-59), who wrote on the special importance in America of community organizations for a healthy civic life and local democracy, would have liked the Bradford Game Supper. “The health of a democratic society may be measured by the quality of functions performed by private citizens,” he wrote.

And Norman Rockwell would have found a subject for a magazine cover or two in this escape from the increasing sleaziness of American life.

It snowed in the hills on our way back to southern New England. Winter is pressing in.

Bid on a Rockwell!

This just in from the National Museum of American Illustration, which sends New England Diary images from its astounding collection from time to time. The museum is on Bellevue Avenue in Newport, R.I.

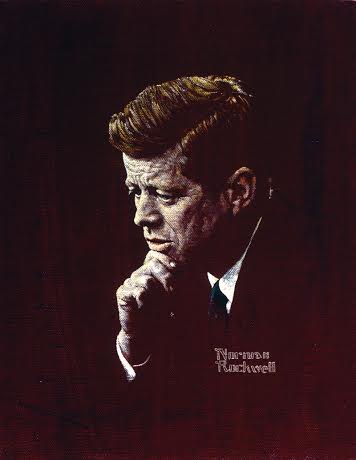

"To allow all of our supporters and patrons to purchase their own original illustration artwork and contribute to our goal of establishing an Endowment Fund, the National Museum of American Illustration's 15th Anniversary Benefit Auction is now open for bidding online. To view the auction and bid, please visit http://www.32auctions.com/NMAIBenefitAuction . If you would like to place an absentee or phone bid to participate in the live auction on July 30, please see the attached bidder registration form.

"Among the many wonderful auction items, there is: Norman Rockwell’s historic Portrait of President John F. Kennedy (shown above) painted for the April 6, 1963 Saturday Evening Post cover; Maxfield Parrish's ethereal 1901 Scribner's illustration, Twilight Had Fallen; John Falter's unique perspective on an exciting baseball; two J.C.Leyendecker studies for Saturday Evening Post covers; illustrations of beautiful muses painted by Howard Chandler Christy, Philip Boilleau, Harrison Fisher, and F. Sands Brunner; a Bemelmans from Madeline’s Rescue; Mead Schaeffer’s South Seas pirates; and much more! The proceeds from the sale will benefit the NMAI’s Endowment Fund, to continue the Museum’s mission into perpetuity.

"The online bidding will continue until Thursday, July 30, at 10 a.m. and the auction will conclude at the 15th Anniversary Gala hosted at Vernon Court, the Museum's home, in Newport, Rhode Island. The Gala begins at 6 p.m., and items will be available for silent bidding. At approximately 9:30 p.m., the top lots will be sold by an auctioneer in a live event. Bidding on all other lots will conclude at Midnight on July 30th. To ensure winning of a lot, please see the attached absentee and phone bidding form to place a bid for the live event.

"We welcome and encourage all our supporters to bid online and to register for Absentee and Phone bids. For assistance and additional information, please call the NMAI at 401.851.8949, or visit our Website, http://americanillustration.org/''

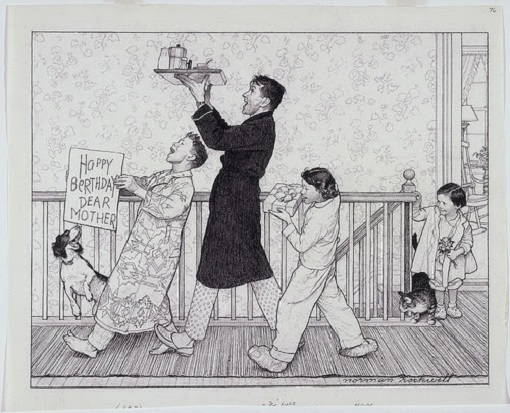

Norman Rockwell's world and ours

"Mother's Birthday'' (conte crayon drawing), by NORMAN ROCKWELL, at the Springfield (Mass.) Museum, through Jan. 4, 2015 in the show "Norman Rockwell's World: Reinterpreting the American Tradition in the 21st Century''. (Picture is a gift of MassMutual.)

"Mother's Birthday'' (conte crayon drawing), by NORMAN ROCKWELL, at the Springfield (Mass.) Museum, through Jan. 4, 2015 in the show "Norman Rockwell's World: Reinterpreting the American Tradition in the 21st Century''. (Picture is a gift of MassMutual.)

This image was one of 21 drawings that MassMutual (the Springfield-based insurance company) hired Rockwell to do in the '50s and '60s that celebrated such traditional "American themes as hard work that appealed to corporate America,'' says the Springfield Museum blurb for the show. (Note that the father needs a shave!)

"So with today's fluid definitions of family, love and success and our fast-paced self-motivation, how do we make the work of Rockwell and the themes he so passionately believed in relevant to the world as we know it? That's what makes this exhibition so enlightening: comparing and contrasting the important themes of today with the depictions of family, work and leisure given to us by Rockwell himself.''

Ads these days tend to be much edgier and hipper than back then. But Rockwell, despite his rural image, was a very sophisticated man, well attuned to the culture around him, albeit sometimes in flight from it, too. And, I think, he had a rather tragic view of life that led him to paint the world that he wanted rather than the messy one he lived in.

How might he have adjusted his illustration approach today so that his work would remain salable, long after the heyday of print mass-media illustration in which he thrived in the early and mid 20th Century? I suppose he would have learned Photoshop....

Would his celebration of "traditional family values'' appeal to Silicon Valley start-up people?

In any event, his work now is more popular than ever, in what might reflect our escapism from our present attention-deficit-disordered, too fast and too ironical world, and our admiration for Rockwell's superb craft and professionalism. Ah, if only we of a certain age who remember seeing these images for the first time on paper (in magazines) had only appreciated back then how special they were, and that they would last.

Third person rural

By ROBERT WHITCOMB

While driving through the Vermont hills a few weeks ago, I thought about two artists much associated with New England’s rural parts — Norman Rockwell and Robert Frost — and the relationship between their lucrative rural public personas and private lives. No surprise that there was quite a gap! For one thing, they were born outside New England — Frost in San Francisco and Rockwell in New York City — and grew up in cities. More importantly, their public images were, and are, at considerable variance from their personal lives.

Norman Rockwell has been much in the news again lately because of the new book “American Mirror: The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell,” by Deborah Solomon. In it, she not only discusses Rockwell’s genius as an illustrator, but also a private life that was often quite tormented. (Like, I would guess, most lives.)

Ms. Solomon discusses Rockwell’s depression and anxiety. And she speculates (to the dismay of the artist’s family) that his life may have been complicated by homoerotic longings that may (or may not?) have expressed themselves in his many pictures of winsome, Tom Sawyer-like boys and handsome square-jawed men. He also had three troubled marriages and was a hypochondriac — and to the pleasure of his millions of fans, a workaholic.

Stockbridge, Mass., the Berkshires town whose scenes provided many of the ideas behind Rockwell’s famous illustrations, is also the site of the Austen Riggs Center, the mental hospital whose staff has treated many celebrities. Ms. Solomon says that Rockwell and his second wife, Mary Barstow, an alcoholic, moved there from Arlington, Vt., so that Mrs. Rockwell could be treated for depression. Rockwell himself used Austen Riggs’s services.

And yet the pictures that Norman Rockwell painted of the town are mostly upbeat — evoking a small-town communitarian paradise. “I paint life the way I want it to be,” he famously said.

Then there was the mating of modernist and 19th century poetry that is the great work of Robert Frost. Frost, like Rockwell, was a city boy whom the public came to primarily associate with rural New England themes, but innocent and Arcadian his poems are not. Many evoke a chilly or even malevolent universe. (My favorite is “Design.”) Far more Ethan Frome than Currier & Ives.

But as his fame spread in the English-speaking world (he first became well-known in England, where he lived in 1912-15), that he looked like Hollywood’s idea of a Yankee farmer, and his folksy genial manner (for public consumption, anyway) tended to overcome in the public mind the darkness of his poems. He could have been a character in a Rockwell painting. This was in part intentional: Being seen as a charming cracker-barrel philosopher/poet brought in the lecture and poet-in-residence fees. He became the most famous poet in America.

Thus we have the curious transformation of the deeply intellectual Frost (whose characters were mostly ordinary country people, whose speech patterns and emotions he was deeply familiar with) into an icon of popular culture.

Consider the revision in Norman Rockwell’s reputation from “merely” a “fine popular illustrator” to being seen as a kind of great artist, with aesthetic links to other masters going back to the Renaissance. It takes a long time for society to figure out what it really thinks of its artists and politicians.

***

Memoirs have been one of the comparatively strong parts of the book business in recent years. With aging Baby Boomers, expect a lot more. A few recent ones:

‘’Whiplash: When the Vietnam War Rolled a Hand Grenade Into the Animal House,” by Denis O’Neill, is a mildly fictionalized account of the 1969-1970 academic year at Dartmouth College. O’Neill is a journalist, screenwriter and musician. On Dec. 1, 1969, the Selective Service System held the first lottery since World War II for the draft, bringing great anxiety to some and relief to others, and “The Sixties,” as we know them, reached their crazy crescendo. (You could say that “The Sixties” as a cultural phenomenon didn’t really end until, say, 1972.)

Then there’s Rhode Island investment mogul Tom DePetrillo’s book about the downs (including personal bankrupty) but bigger ups of his career. He was one of 11 children and a school dropout before he made a fortune as an investor. The book provides chatty and colorful advice and observations on business, public policy, politics and life in general.

Finally there’s Ralph Barlow’s “Beneficent Church in Providence: A Church Engaged with an Emerging New World,” the Rev. Mr. Barlow’s memoir of running the church from 1964 to 1997, during which this downtown Congregational institution’s experience included many of the recent social upheavals of American society.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb4@cox.net), a biweekly contributor, is a Providence-based writer and editor. He blogs at newenglanddiary.com.

The way he wanted life to look

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), “The Bridge Game,” 1948, oil on canvas, published by Saturday Evening Post, May 15, 1948 cover Image Courtesy of National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI., cover image © SEPS: www.curtispublishing.com.

There’s another picture below.(Rerunning this posting from the pre-renovation version of New England Diary a few weeks ago.)

The New York Times seems to be on a Norman Rockwell kick, with a long review of a new book out about him and a travel piece about Arlington, Vt., where he lived for a long time.

That was before he moved to Stockbridge, Mass, in the Berkshires, to, among other things, be closer to Austen Riggs, the mental hospital identified with many celebrity patients.

As Deborah Solomon (who also wrote the travel story) writes in “American Mirror: The Art and Life of Norman Rockwell,” his life was far more complex and darker than most of his beautiful art. That he was a troubled man (who ain’t?) is not news, but Ms. Solomon puts it together very well indeed.

He was apparently conflicted about homosexual longings, had three troubled marriages and was a lifelong hypochondriac. The Thoreau line about “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” comes to mind. Still, he obviously found much comfort and joy in his studio. Do too many writers these days make too much of sexual conflicts? Maybe a highly creative person’s biggest trauma is the difficulty of finding meaning in a seemingly chaotic world, a torturous search for ultimate meaning.

Some of this reminds me of the strange story of Robert Frost, whose public image as a sort of quaint, folksy, friendly rural poet was so false. In fact, Frost, a kind of Modernist, used his New England settings to explore existential quandaries; and he could be a very nasty man.

Many of his poems were dark, dark, dark. Take a look at his poem design “Design”.

But, in part because his folksy image got him many lucrative lecture gigs, he played along with it, to a point (while winking).

But then, behind almost family’s door is conflict and mental illness of varying seriousness. In some way, maybe imaginative repression and diversion, Rockwell got great popular art done despite, or because of, his problems, through vast technical skill, knowledge of other masters’ work and a rich visual imagination.

The Rockwell renaissance also reminds me of how much many of us miss the golden age of magazines, such as The Saturday Evening Post, for which Rockwell did so much work. The weekly arrival of pubs such as The Post and Life magazine was a joy that I, anyway, have never found with TV, the Internet and newspapers (with the possible exception of the beautiful old New York Herald Tribune).

That is probably ungrateful, since newspapers paid for most of my upkeep for almost 44 years.

Speaking of the past, I was pleasantly surprised to see that John Wilmerding, my art-history professor of almost a half century ago at Dartmouth, was the reviewer of Ms. Solomon’s fine new book. Mr, Wilmerding, an heir to great Havemeyer sugar fortune in New York, also has one of America’s greatest collections of American art, much of which he is giving away.

The best places to see Rockwell work are the National Museum of American Illustration, in Newport, and, the Norman Rockwell Museum, in Stockbridge.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), ”Volunteer Fireman,” 1931, oil on canvas, published by Saturday Evening Post, March 28, 1931 cover image Courtesy of National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI. Saturday Evening Post cover image © SEPS: www.curtispublishing.com