‘The world as given’

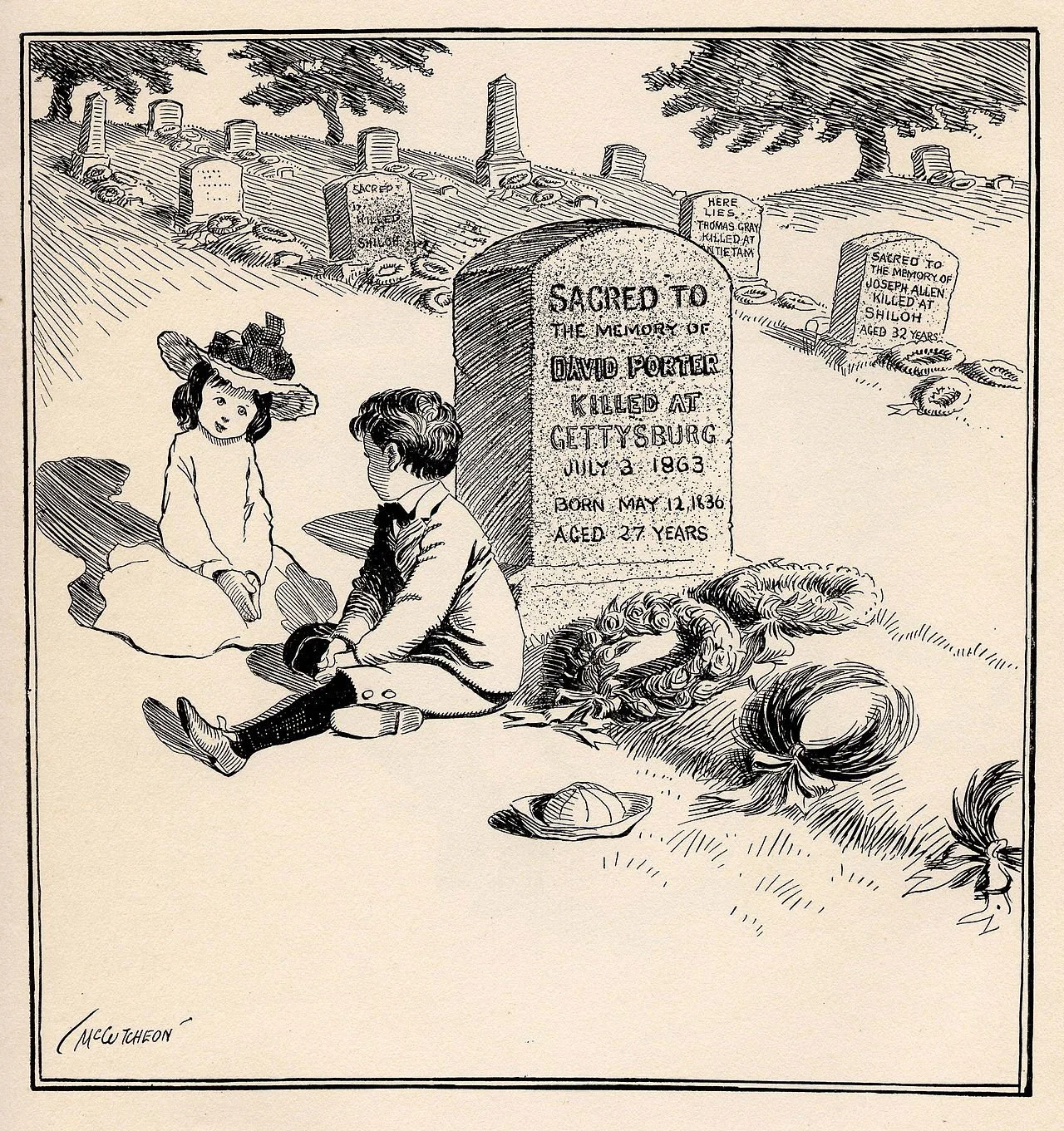

"On Decoration Day" (the earlier name of Memorial Day) political cartoon c. 1900 by John T. McCutcheon. Caption: "You bet I'm goin' to be a soldier, too, like my Uncle David, when I grow up."

“To say that war is madness is like saying that sex is madness: true enough, from the standpoint of a stateless eunuch, but merely a provocative epigram for those who must make their arrangements in the world as given.”

―John Updike (1932-2009), American novelist, short-story writer, essayist and literary and art critic. He spent most of his life on the Massachusetts North Shore.

Memorial Day in World War II

Members of the American Legion (veterans) and Boy Scouts mark Memorial Day in tiny Ashland, Maine, in 1943. Most of the town’s young men were off serving the effort to win World War II. The town calls itself “Gateway to the North Maine Woods’’.

— Photo by John Collier for the Office of War Information

Llewellyn King: Welcome to summer -- the American season

Old Orchard Beach, in Maine

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The calendar opines that summer starts on June 20, but we know better. Metaphorically, it starts on Memorial Day, when we give thanks to those we honor, those who gave their lives for their country. Then it is, “Beach, ahoy!”

Memorial Day weekend signals the beginning of summer as if a flaming taper were applied to black powder and a cannon fired, joyously marking the sun’s reascendance to its throne.

Summer is important everywhere: to the British who try to catch a few elusive rays under their perfidious sun; to the French who shut their country down in August, and claim their spots on the crowded Mediterranean and Atlantic beaches; or to the Germans who take the summer break as a time to earn bragging rights on how far away and in which unlikely places they took their generous six weeks of vacation.

It isn’t that we Americans don’t travel. But it is here, at home, that we worship summer with the adulation of the sun. It is here we celebrate warmth, sand, water and barbecues. It is here that summer is most adored, most longed for, and most remembered for everything from young love to wraparound family togetherness.

All the world celebrates summer, but Americans exalt in it; treasure it as no others around the world.

Summer is woven into our culture, from those beach movies of the 1950s to its endless evocation in popular songs.

Growing up in Africa, I was bemused and confused by all of this summer worship coming out of the radio. We took summer for granted. It incorporated our rainy season and was a little less lovely than winter -- when the weather was so fair that the radio station (there was but one, and no television station ) didn’t announce the weather for six months. How many ways can a weather forecaster, even the most creative, say “perfect”?

Yes, on the Zimbabwe plateau (highveld), close to the equator, the weather is perfect and, if I might say so, perfectly boring.

No, give me the change of season. Let me join other Americans in celebrating the euphoria that breaks out every June when we say goodbye to dull care and embrace the bounty of summer, of cookouts and hikes, of shorts and tank tops and of going sockless.

From the beaches to the lakes, summer draws us to the water; some just want to bake their winter-ravaged bodies in the hot sand, others want to take to the water in or on everything from canoes to paddle boards, and from dinghies to great schooners.

The call of the water is loud in summer for many Americans but so, too, is the call of the mountains, and the glory of the National Parks beckons with a seductive finger.

The American summer is inextricably tied up with coming of age, of first love – indeed, the first of many first things. But it also enchants the oldsters. It is the time for family integration, when grandchildren and even great-grandchildren can be indulged from Portland, Maine, to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, and from the Upper Michigan Peninsula to San Diego.

Summer thrills, stocks the memory bank, as even Alaska turns from the epitome of winter to a lush and tempting land where the outdoors offer a cornucopia of joys.

I have been lucky enough to spend summers around the world, so I can report that nowhere is summer embraced with such near-religious fervor as it is here in the United States; nowhere is the sun’s return to full raiment of majesty so celebrated and adored.

Remember this Memorial Day those who fell so that we might be free to fire up the grill and soak up the sun. It shines so lovingly on America.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Llewellyn King: 70 years ago, the handsomest man

Seventy years ago, we celebrated the end of World War II in Europe. That celebration is not the first memory of my childhood, but it is one of the clearest.

I was a five-year-old boy in Cape Town, South Africa, proudly displaying a paper Union Jack, the familiar British flag, and watching the victory parade. I often wonder where the flags came from – before offset printing and photocopying – in time for the parade. Someone knew that victory was at hand.

There was a palpable, universal happiness – though more subdued, I am told, than the outbursts which greeted the end of World War I. For me, that was the best parade ever. It was wonderful to see people grabbing each other, doing little impulsive jigs in the street.

Marching in the parade was the handsomest man I had ever seen, or have seen since: my father in his best Royal South African Navy uniform of a chief petty officer, engine room. My father was a wonderful man in many ways. He was not lettered, but extremely kind and dutiful, and loved for those things -- not for being handsome. But I tell you, that day he was handsome.

It was not until 1998 that Tom Brokaw called them “The Greatest Generation,” in a book of that name. Maybe all who go to war are the greatest generation. Maybe, every father who survives is unbearably handsome to someone.

Memorial Day is upon us and our veterans -- maybe veterans everywhere -- will be briefly remembered. The Greatest Generation was, perhaps, the last time that a generation was defined by its sense of duty. That was true of the men and women who peopled my young life.

My father sold our home and few possessions, in what was then Southern Rhodesia, to serve. He was turned down for the British army in Rhodesia because an arm he had once broken had not mended properly. He had heard that the Royal South African Navy would be more tolerant. His acceptance by the navy was not a certainty, and we had no money. But we made the long, hot, six-day journey to South Africa by train to no known future; my father, mother, brother and myself, all going off to war because that is what was done. That is what the men of the Greatest Generation did because it was your duty to serve.

My father was not alone. I grew up hearing other stories of how people had gone to great lengths to serve and, having gotten into the armed services, how they did everything they could to get into the fight, not to serve at a distance in a British dominion, as South Africa then was. That is how South African pilots came to serve in the Battle of Britain.

In those days, patriotism was organic here in the United States and around the globe. Not every last man of military age was a patriot, but most were. It was the deep-seated culture.

When it was over, those who survived WWII were welcomed home with celebrations, appreciation and reverence. Alas the warriors from more recent wars, Korea, Vietnam, Kuwait, Afghanistan, Iraq and lesser conflicts, have come home to cold comfort. No parades, no five-year-olds with flags -- and little place in the tapestry of the national memory. No recognition of their inalienable right to honor.

War is not everyone’s business anymore. Vietnam was the first war where patriotism was not part of the equation. Today, with a professional military, it is not the business of the armchair patriots with their slogans, urging others to take up arms.

When the World War II Memorial opened on the Mall in Washington, in April 2004, I went there. I did not like it, architecturally; I was disappointed. But then men with canes and in wheelchairs began arriving, smiling and shedding occasional tears. It was important and moving to them, those handsome men. My father would have loved it; now, I like it well. Memorial Day weekend is at hand.

Llewellyn King (lking@kingpublishing.com) is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.