‘On a big expedition’

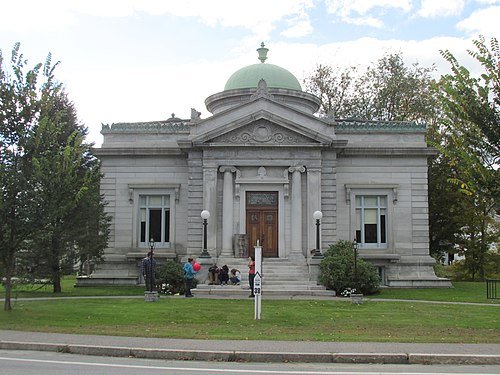

Shedd-Porter Memorial Library, in Alstead, N.H., was designed in the Beaux-Arts style by Boston architects William H. McLean and Albert H. Wright. It was built in 1910 as a gift from John Graves Shedd and Mary Roenna Porter in memory of their parents.

“The New England Thinkers

”Don't rush my sitting under the finch book tree. It has been dark for ten days and like two eyes feed one brain, we go driving. We are on an expedition to see the big numbers and wreckage of the floods.’’

— From the poem “The Continent Behind the College,’’ by Lesle Lewis

Ms. Lewis teaches at Landmark College (the college referred to), in Putney, Vt., and lives across the Connecticut River, in Alstead, N.H.

Sophie Lampard Dennis: The sad decline of face-to-face encounters

Via the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Remember the faculty lounge? When I began at my current institution back in 1999, there was one in every building—sometimes two! This public space—complete with industrial furniture, coffee pots smoldering on burners, and a mini-fridge with sticky notes all over it reminding people to clean out their stinky sandwiches—was higher education’s version of the office water cooler.

Faculty and staff connected, people in different departments shared ideas, jokes and snacks, and mainly people let off a bit of steam while taking a much-needed mental break during the day—often while they also made photocopies (remember those?). Many a problem or conundrum was vented, birthday cards signed (and cake shared), and aha moments with students were exulted over in the faculty lounge. NPR stories were re-told. Most importantly, this simple, open and welcoming space engendered a sense of community. I miss it.

Lately, I have been lamenting the increasing loss of face-to-face interaction. The prevailing attitude of taking care of business without having to actually get together has taken hold across all realms of society. Despite the also-growing trend toward “open workspaces,” there seems to be less and less contact with other human beings as a matter of course in life these days. “No need to meet; we can take care of that with email” has become a consistent mantra- and my nemesis—even as I imagine with dread the numbers of “reply all” to come.

Recently, “I’ll set up a Google Docs account and we can use that to upload information rather than getting together” has taken hold. I am beginning to wonder whether I should, perhaps, begin sending my avatar to teach, thereby staying in my office for the entire working day. Or more to the millennial point—perhaps a class conducted entirely in Facebook Messenger? Class attendance would probably be greatly increased!

The “mail room” where the painted wood faculty mailboxes hang on the wall in alphabetical order—seems mostly a tribute now to a time long gone wherein actual business took place in this room and people converged, if briefly. Now, those mailboxes only occasionally hold a paper phone bill—and surely, these could be generated electronically. The room is no longer a help for those looking for human contact. Even the bulletin board in this room (for those millennials reading this article, that’s a location for actual paper announcements to be posted using thumb-tacks), which at one time held a plethora of messy communications, has been left in the dust as the electronic version has prevailed (so neat! So tidy! No trees killed!).

Campus projects over the years have caused the old lounges, one-by-one, to be converted into other types of spaces. As student programming has expanded and entered the 21st Century, so has the need, for example, for enhanced labs for computer gaming courses as well as for offerings in video production and electronic music. Computers have taken hold where, once, faculty congregated. So here I am, in the comfort of my own lonely office, on a hallway of offices, in a building of offices, with nowhere to wander to. Am I more productive? Maybe. I eat my lunch at my standing desk (don’t get me started about what happened to a common lunchtime!) as I grade papers, while simultaneously receiving and responding to all mail, as well as perusing the electronic faculty bulletin and checking Google Docs for new uploads from my current task force or committee.

The actual faces of my colleagues and friends as seen at one time in person, have now been replaced by a “profile picture”—a tiny square with a face in it- which pops up with their email. At least when I have something funny to share with a colleague, or an aha moment with students to report (I haven’t figured out how to share cake this way yet)—there is an emoji for that: ☺ .

Sophie Lampard Dennis is associate professor of education at Landmark College, in Putney, Vt.

Sophie Lampard Dennis: The college homework challenge

PUTNEY, Vt. "How do we get them to do the homework?''

This is the most common question I hear at conferences. Inevitably, upon the conclusion of my presentation, which focuses on working with college students who may experience barriers to learning—who are “at risk” in some way—somebody raises his or her hand and asks with a sense of frustration, “Yes, but, how do I get them to do the homework?”

It seems that instructors and professors—from community college to the Ivy League—are concerned by the lack of work completion in their courses, and therefore by student level of preparedness for class, or indeed, college.

It is interesting that nobody considers teaching students how to do homework, yet it is universally expected (or hoped?) that all students are adept at these skills and will have become experts by the time they arrive at college. Work completion is typically a very large portion of course expectations—often beginning on day one—and it is generally understood that for every hour of class time a successful student should put in an hour or more of study time. We all assign out-of-class work. In fact, it is a hallmark of the college experience. But what does it mean when students don’t do it? And, importantly, should we have a role in supporting those struggling with work completion?

You will notice that I used the term “skills”—plural—when describing the process of completing a homework assignment. Work completion is not a single skill that all students “get” simply by being in a learning environment and attending class. The simple act of turning in an assignment on-time is the culmination of a series of steps, any of which could be challenging.

As a freshman seminar professor, I introduce this as a topic of conversation early in the term with the question: Why might a student neglect to turn in a homework assignment? We fill the board with explanations, and we run out of space. (Ran out-of-time, didn’t record the assignment properly, forgot, didn’t understand the assignment, wasn’t sure how to begin, wasn’t sure what the teacher wanted, couldn’t find the assignment on the course website, lost the book, didn’t realize when it was due, wasn’t interested in the topic, never learned how to take notes/write a summary/highlight, didn’t save it and lost all the work, finished it but don’t consider it good enough to turn in …)

This list may sound like a litany of excuses, but each actually represents very real and authentic explanations for why a student may be unprepared to turn in the homework. As teachers, we can view this language as excuse language (thereby making it not our problem), or we can choose to see it for what it usually is: a student needing guidance on some element of the process.

As faculty, we need to understand that very rarely does a student neglect to complete an assignment on purpose. They would rather be able to do it. When instructors allow ourselves to contemplate this, only then will we respond with compassion rather than frustration, and get back to what archeologists call “first principles” and teach. Homework completion skills can, and should be, taught explicitly. Consider now the multiple sets of skills a student must have adequate control over to complete an assignment well.

First, the student must have an effective method for recording the assignment; she must also understand it fully and be able to predict how much time it is going to take, and how this fits into the time she needs for her other assignments from other classes. Managing her time effectively will be critical for completing several different types of assignments in the evening. She will need to be able to prioritize assignments depending on how big or important some are as compared to others. She must find relevance in the work in order to consider it interesting enough to engage in. Next, she will need to be able to self-activate in order to begin working, and her focusing skills will then need to kick in in order to sustain momentum. She must also have good enough technology skills for the task, and a working file-management system for keeping organized for all of her classes. The student must understand the systems for electronically locating assignments and submitting work (these vary instructor-to-instructor.)

Other areas that the student must adequately manage for work completion include making sure to eat well for sustained energy, and knowing how and when to take breaks in order to recharge. She will have needed to get enough sleep the night before, and she must understand and have strategies for managing stress. While working, she must not allow herself to become distracted too much by friends or Facebook. Also, she must not have perfectionist tendencies in order to feel that the work is good enough to turn in. It would be helpful if she does not have personal baggage around the subject at hand or it will be emotionally charged and more difficult (math anxiety, for example). If the assignment needs to be turned in as hard-copy, she must be able to organize her time in order to plan to get to the library before class to print.

All this assumes that she actually holds the academic skills required—notetaking, highlighting and finding key words, for example—to do the academic task assigned. And most important of all, she must know when and how to ask for help.

So, how do we get them to do the homework?

It begins with understanding the complexities involved in actually doing the work. We can discuss this with our students to help them realize how multifaceted a process homework completion really is—especially at the first-year level. When students begin to see work completion as a series of steps, the skills for which can be learned and practiced, it will demystify the task, and particularly for those who struggle, this will support fewer feelings of being “lazy” or “stupid’ as they work to address the skills they realize may be holding them back.

Instructors can frontload support by directly supporting students in learning and practicing these important skills, beginning with asking them on day one what their assignment book or planner system is, and subsequently reminding them to use it each time they get an assignment. Ask them to predict how much time the assignment will take as they write it down and consider it, and to think about when they plan to work on it; they can write this information next to the assignment. Help them in the beginning of the term by chunking up the assignments into parts to be completed one step at a time. Additionally, we can help them make, and systematically use, a visual schedule for organizing their work time. Actively setting goals for the week during class—perhaps in their planner or by journaling—can be helpful. Some students may need to re-verbalize the assignment to the instructor before they leave the room, or have a quick back-and-forth about it for full comprehension.

This is a good time to ask students questions about homework timing and priorities; do they, for example, know where the learning center is, whether they have used a class website effectively to locate the assignments, and a reminder about where and when office hours are held.

Instructors can also backload support—when students do not turn in the homework—by asking the right questions to help them hone in on the point in the chain that is weak. Instructors can say: Let’s talk about why the assignment was not completed. They can ask questions such as: Did you write it down and understand it when it was assigned? Did you have a hard time sitting down and starting it? Did you lose focus after a while? Were you lacking the academic skills needed for this assignment? Should you have asked for help? Had you underestimated the amount of time this would take? Were you too tired/too hungry?

A positive response to any of these questions can be followed up with support: suggested strategies, templates that can be used, articles offered (helpful articles on the topics of procrastination, motivation, perfectionism, for example), and in-class activities designed. This form of non-judgmental questioning can help students, and the instructor, pinpoint where the breakdowns may be occurring and very importantly, what the student may actually be doing well. For example, she may be diligently writing the assignment down and starting it, but tending to get stuck in the middle when focus wanes as she gets tired; a suggestion to start her homework earlier in the day may help!

Many students only perceive failure when they do not turn in work, but pointing out what she is doing right in this complex process can be empowering and a catalyst for positive change.

I would suggest reserving some class time early in the term for homework-completion skills practice. Have students in small groups share homework strategies that work for them. Put together and make accessible throughout the term a list of class resources for various kinds of homework help; some tech-savvy students may be willing to be available for help with tech questions, others may be willing to be involved in a study group, for example.

The next time a student says “I didn’t feel like it” or “I didn’t get it” or “it was a stupid assignment,” ask them to talk a bit about why; I have found that this language is always covering a real, teachable issue. “I didn’t get it” often suggests the student would benefit from a comprehension check before leaving the room, and a skills-check during an office-hour appointment. “It was stupid” is usually code for the existence of some level of an emotional component that may be unrecognized, perhaps related to a past school experience with the subject or task. “I didn’t feel like it” implies difficulty in finding relevance in the task; helping the student tap into goals they have for themselves, which the course fits, can begin to solve this issue (perhaps it is a requirement in their major.)

Finally, it is incumbent upon instructors and professors to meet the students wherever they are in the learning process, and with so many of them today struggling with the skills associated with independent out-of-class work, why not view this issue as a teachable moment rather than the elephant in the room that we may not choose to address? Acknowledging the great complexity of the skill-set associated with completing an assignment, giving language to what is working and naming the challenging areas, and then offering methods of support has the power to move students from being stuck to taking action, and will support all students in being more prepared for class. Faculty, too, have the opportunity to step away from feeling frustrated and helpless and into a place of empowerment as they get back to their roots and teach.

Sophie Lampard Dennis is an associate professor in Landmark College's First-Year Studies Department. This piece originated on the online news site of the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org).