Chris Powell: Why no one outbid the asset-stripper Alden for famous newspapers

MANCHESTER, Conn.

More complaining about Alden Global Capital's dismemberment of the storied newspapers it recently acquired from the Tribune chain appeared this month in a long and -- to journalists, anyway -– infuriating essay in The Atlantic magazine by its reporter McKay Coppins. {Alden, an asset-stripping operation, also owns the Boston Herald.}

This dismemberment, Coppins noted, includes the Chicago Tribune's former headquarters, the landmark Tribune Tower, which has been converted into an apartment building.

But at least what remains of the newspaper still has modest offices in an industrial area across town near the newspaper's press. Another former Tribune property, The Hartford Courant, no longer has even that much. Somehow Alden acquired the Courant's headquarters on Broad Street in Hartford and kicked the newspaper out even before acquiring the Courant itself and the other Tribune papers. The Courant now seems to be entirely a work-from-home operation, and like several other Connecticut papers, including the Journal Inquirer, now is printed by the Springfield Republican. The Courant's address has become a post office box.

From Los Angeles to Chicago to Baltimore to New York and to Hartford, how the mighty have fallen, though the journalists who remain in the formerly great papers of old soldier on bravely and sometimes well.

Of course, the dismemberment of the former Tribune papers is just part of the decline of serious state and local journalism generally. But while Alden may seem especially predatory in its liquidations, the company is not a cause but just a symptom of what has gone wrong with the news business -- and not just the rise of the Internet and the transfer of advertising there but, more so, the public's loss of interest in state and local news.

This is in large part a matter of declining demographics.

After all, newspapers survived major challenges from competing new technologies before -- first radio and then television, whose main products are entertainment, not news, and whose state and local news reporting always have been and remain weak. Even now anyone who wants to be well informed about state and local government and community events and to participate in public life has to subscribe to a newspaper.

While some places -- including Connecticut -- now have a few Internet sites providing state and local news, most are niche operations that don't attempt to serve any area comprehensively. They concentrate on government and their audiences tend to be smaller even than newspaper audiences. They are not any more profitable than most newspapers, and many are operated as nonprofits supported by donations, if sometimes large ones from foundations. This method of operation is hardly a business plan and may subject the internet sites to more political pressures than advertising subjects newspapers to.

But if more people wanted state and local news and commentary, newspapers and news-based Internet sites would have more readers, and as their audiences grew, they might become profitable from increased advertising.

The movement to convert newspapers to nonprofits and to operate Internet news sites that way presumes that substantial interest from the public is no longer attainable.

It is hard to argue with that presumption. After all, throughout the country and even in Connecticut most young people, the products of social promotion, graduate from high school without ever mastering basic math and English. Most gain little if any knowledge of the country's history and civics. Even in Connecticut, a comparatively wealthy and well-educated state, the typical high school graduate or college freshman cannot identify the three branches of government. (You know: the lawyers, the teacher unions, and the liquor stores.)

That is, most young people are not being prepared to become citizens in a democracy, much less followers of state and local news.

This may be the underlying reason that Alden is liquidating so much of the former Tribune papers, draining away their capital, like their real estate, and why no one outbid Alden for the Tribune papers with the confidence that solid journalism could be made profitable again. For the future isn't just disruptive technological change but also social change, which may be far more disruptive.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

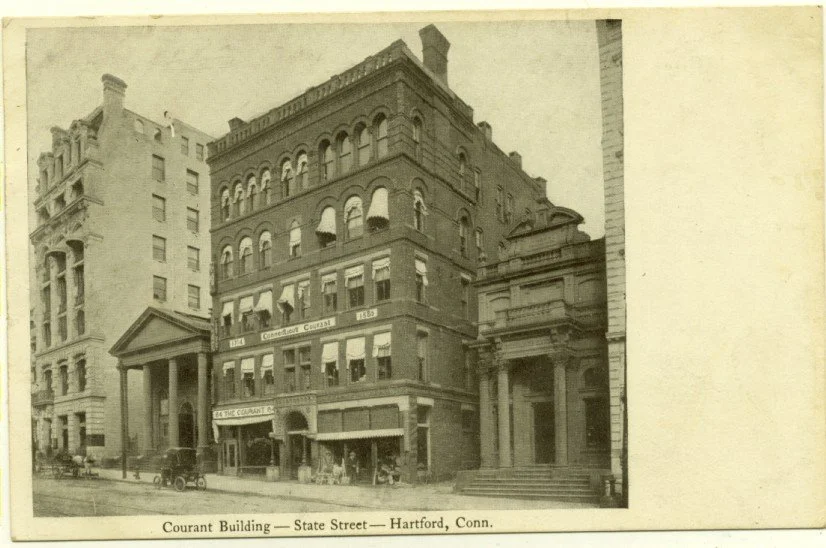

An earlier Hartford Courant Building, in about 1900

Chris Powell: Is infamous hedge fund Alden saving or killing newspapers?

The now closed Hartford Courant headquarters building

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Nearly everyone wanted Tribune Publishing Co. to be purchased by someone other than Alden Global Capital, since the hedge fund is seen as an "asset stripper." Indeed, months before acquiring the shares of Tribune it didn't already own, Alden had managed the neat trick of stripping the Hartford Courant of its own building, leaving Connecticut's largest newspaper homeless.

But while nearly infinite money lately has been floating around the country and zillionaires abound, nobody offered more than the $633 million Alden offered to take Tribune private. Despite the decline in the newspaper industry, Tribune is said to remain profitable and to have millions in the bank, and the eight newspapers it owns apart from The Courant include some storied names: the Chicago Tribune, the New York Daily News, and the Baltimore Sun.

So the lack of other bidders suggests wide scorn for the industry's future.

That's why bemoaning Alden is so hypocritical, as it was the other day when Connecticut U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal joined Courant journalists at a protest rally. "Get a better buyer," Blumenthal implored, even as his own family easily could have afforded becoming a major partner in a rival bid -- but didn't.

But rich people indifferent to the public interest in sustaining newspapers are not the main culprits of the industry's decline.

Troubled as they are, newspapers remain the country's primary source for serious news, news beyond idle distraction and titillation -- news about government, community, business and life in general. Television and radio steal from newspapers shamelessly. Some state and local Internet news sites do great service but their "business model" is only charity and thus not so reliable.

The biggest problems for newspapers are the public's diminishing interest in serious news and the country's worsening demographics. Literacy and civic engagement long have been declining while poverty and violence have been increasing, especially in such cities as Chicago, Baltimore and Hartford. It takes courage enough to invest in the newspaper business generally, and heroism to invest in newspapers in disintegrating cities.

Even in Connecticut it is a matter of general indifference that half the state's high school graduates never master high school English and math and so enter adulthood unprepared to be citizens, much less newspaper readers -- or readers at all.

So horrible as it may seem, for the moment there may be nothing to do but to root for Alden, especially since before acquiring Tribune it already had acquired a hundred papers across the country and was the country's second largest newspaper chain. Alden President Heath Freeman says the company's goal is "getting publications to a place where they can operate sustainably over the long term."

Of course, to "operate sustainably" may require weakening Alden's papers more. But then the content of nearly all newspapers long has been weakening along with their circulation. For in the end the investment newspapers rely on most is not that of their owners but their subscribers, and nobody needs a newspaper just to keep up with the Kardashians.

xxx

\If the United States is ever attacked again, nobody should seek advice from Connecticut U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy.

“Israel," Murphy said the other day, "has the right to defend itself from Hamas's rocket attacks, in a manner proportionate with the threat its citizens are facing.”

But no country wins a war with a "proportionate" response to attacks. Wars are won with enough force to defeat the enemy and eliminate its war-making capacity. Japan started its war with the United States by sinking a few ships at Pearl Harbor, but the United States won the war by sinking nearly all Japanese ships and leveling the whole country, concluding with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In a recent newspaper essay Murphy also wrote that schools need fewer police officers and less student discipline and more counselors and social workers. But disruptions by students in school are helping to drive the exodus from the cities. Murphy misses that problem and the underlying one, since he fails to ask:

Where are all the messed-up kids coming from?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Chris Powell: Better journalism needs a better public

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Hartford's City Council is worried about the future of the city's newspaper, The Hartford Courant, whose management and ownership have been in turmoil on top of the stresses imperiling the newspaper industry generally.

Like most regional and local papers, The Courant today has much less staff, content and reach than it had a decade ago, and there are fears that its owner, Tribune Publishing, which is offering all its properties for sale, will relinquish the paper to the chain's largest shareholder, hedge fund Alden Global Capital, which shows little interest in journalism and civic life.

So the City Council is preparing a resolution urging Tribune and Alden to stop diminishing The Courant. "This is our paper," City Council member Marilyn E. Rossetti says, and its decline is "a travesty."

But then Hartford is Connecticut's capital city and has been declining for decades longer than The Courant has. Indeed, as a business matter The Courant long has done better by Hartford than the city has deserved.

It's simply a matter of demographics. Hartford's population is about 122,000, a third smaller than in the 1950s. Thirty percent of its residents are impoverished and almost 22 percent foreign-born and thus less likely to be fluent in English and attuned to civic affairs.

While West Hartford next door has only about half Hartford's population, only 7½ percent of the suburb's residents are poor and only 17 percent are foreign-born. As a result The Courant long has had far more subscribers in West Hartford than in Hartford, subscribers in West Hartford are far more valuable to advertisers than subscribers in Hartford, and downtown West Hartford has supplanted downtown Hartford in important respects.

Being so poor, having a political class dominated by government employees and others drawing their livelihood from government, and lacking a strong middle class independent of government, Hartford is far more vulnerable to political corruption and so needs journalism more. But journalism isn't free, and with its awful demographics the city can't afford it. Serious journalism can't make money in the city.

Even if Hartford got all the journalism it needed, would it make much difference when so many city residents are stressed by poverty, can't read English, can't afford to subscribe, and lack the education necessary to understand and care about public life?

To acknowledge Hartford's awful demographics and their impact on business conditions is not to disparage its residents. For like Connecticut's other troubled cities, Hartford is only what all of Connecticut makes it, and impoverished and dysfunctional cities are actually part of the state's longstanding policy and social contract.

Connecticut's poverty and education policies fail chronically but their primary objective long ago ceased to be to elevate and educate the poor but rather to sustain the government class ministering to them. This supports the state's political regime, and those not directly dependent on the regime tolerate this policy failure as long as they can escape its pernicious consequences -- crime, bad schools, and political correctness -- by moving to the suburbs.

Amid the failure of poverty and education policy, the best that Connecticut's intelligentsia can propose is just to spread the dysfunctionality around, to prevent any escape from it as it grows.

In this sense the suburbs may need journalism more than Hartford and the other troubled cities do, since the suburbs are home to the people with the capacity to understand policy failure and to support change -- middle-class people employed outside government, people who pay more in taxes than they get from government in income.

Why do these people accept the failure of government to reverse the decline of the cities? Maybe it's because their journalism is just as content with the awful social contract as the government class is. Or maybe they are just as demoralized by policy failure as city residents have been.

In any case, there may be a chicken-and-egg situation here. There won't be a better press without a better public, a public willing and able to pay for it, nor a better public without a better press. But how can Connecticut achieve either when most students now graduate from its high schools without ever mastering high school work and are not prepared to be citizens, much less newspaper readers?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.