Who will take care of grandma?

It’s a question we need to answer. As Baby Boomers grow older, the elderly population — seniors who are 80 and older — will increase almost 200 percent by 2050.

Our long-term-care system isn’t ready. Studies show that older Americans prefer home care over institutionalization. But because of low wages and poor working conditions, recruiting and retaining home health aides and personal care assistants is very difficult.

In the end, that means a lower quality of care and fewer home care workers for grandma.

Maybe the home-care industry just can’t afford to pay workers more?

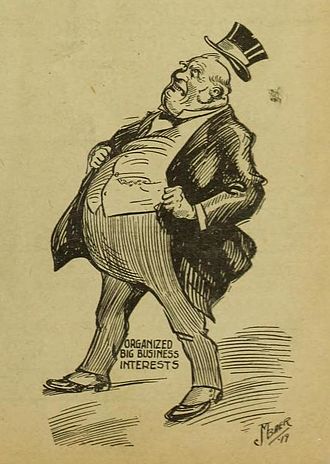

Hardly. The industry has boomed over the past decade. According to the National Employment Law Project, its revenue increased 48 percent, while its CEO compensation ballooned by a whopping 150 percent.

In fact, home care today is a multibillion-dollar industry. Because of rising demand and skyrocketing revenues, Forbes called home health care one of the hottest franchises in the market.

Sadly, home-care workers haven’t shared in the industry’s prosperity. During the same period that revenue soared, average hourly wages for workers declined by 6 percent.

And that’s not the worst of it. Because of a “companionship exemption” to federal labor laws, more than 2 million home care workers today are excluded from minimum wage and overtime pay protections.

Ninety percent of them are women. More than half rely on public assistance to make ends meet.

The Department of Labor has tried to stop the industry from misusing the companionship exemption to pay home care workers less. It passed a new rule that was supposed to make these workers eligible for minimum wage and overtime pay this January.

But before the rule went into effect, several for-profit home-care associations — including the International Franchise Association — successfully sued the Department of Labor to prevent the change.

The industry is claiming that higher wages mean Grandma won’t be able to get the care she needs.

The truth?

Studies show that higher wages mean Grandma will be able to find and keep the best caregiver. And the 15 states that already provide minimum wage and overtime pay for home care workers prove that it’s feasible.

All told, Grandma will be more likely to get the care she needs when her caregivers can earn a living wage.