Philip K. Howard: Public-employee unions, unlike trade unions, corrupt democracy

Chicago teachers marching during a demonstration on Oct. 14, 2019

Massachusetts state militia enter Boston’s Scollay Square (RIP) to restore order during the city’s police union strike in 1919, which was broken, in large part by the rigorous actions by Gov. (and later Vice President and then President) Calvin Coolidge. The strike left a negative opinion amongst many citizens about public-employee unions for many years. There was much crime and other disorder during the strike. Coolidge famously said during the strike:

“There is no right to strike against the public safety by anyone, anywhere, any time. ... I am equally determined to defend the sovereignty of Massachusetts and to maintain the authority and jurisdiction over her public officers where it has been placed by the Constitution and laws of her people."

In a runoff election for mayor, Chicago voters on April 4 narrowly chose former teacher Brandon Johnson over former schools CEO Paul Vallas. Raising eyebrows was the funding of Johnson’s campaign: Over 90 percent came from teachers unions and other public-employee unions. Vallas had the endorsement of the police union, but his funding was more diverse, including business leaders and industrial unions. Just looking at the money, the race came down to this: Public employees vs. everyone else plus cops.

What is wrong with this picture? The new mayor is supposed to manage Chicago for all the citizens, not to benefit public employees. Chicago is not in good shape. In 37 of its schools, not one student is proficient in reading or math. Its transit system is stuck with schedules that serve no one at great expense. The crime rate in Chicago is among the highest in the country. But no recent Chicago mayor has been able to fix these and other endemic problems because the public unions have collective bargaining powers that give them a veto on how the city is run. Frustrated by the inability to get teachers back to the classroom during COVID, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot observed that the teachers union wanted “to take over not only Chicago Public Schools, but take over running the city government.”

This is not just a Chicago problem. Los Angeles teachers walked out of class rooms last month supposedly to support striking service personnel, but Los Angeles lacks the resources to help the service employees because of the indebted inefficiencies in the teachers union contract.

American government has a fatal flaw hiding in plain sight. Public employee unions in most states have a stranglehold on public operations. Voters elect governors and mayors who have been disempowered from fixing lousy schools, firing rogue cops, or eliminating notorious inefficiencies.

Look at almost any public scandal in recent years—failing schools in Baltimore, police killings in Minneapolis and Memphis—and you will find public supervisors who, under union controls, have lost basic managerial tools. Democracy is supposed to be a process of accountability. But there’s near-zero accountability in American government—between .01 and .02 percent in most jurisdictions. Two out of 95,000 teachers in Illinois were dismissed annually for poor performance over an 18-year study period. In the decade prior to the killing of George Floyd, of the 2,600 police complaints in Minneapolis only 12 merited discipline, of which the most severe was a 40-hour suspension.

No wonder democracy is working so badly. Elected leaders come and go, but public unions just say no. How did public employee unions get this power?

Rewinding the Clock

Until the 1960s, public employees were organized like lawyers, doctors and other voluntary professional associations. They had no legal right to compel government to enter into contracts. Many already enjoyed civil service protections, and government work was generally sleepy, not ruthless. But public employees had become a huge voting bloc, and leaders of public employee associations wanted power over how government was run.

Until then, the idea of public employees bargaining against government was inconceivable. FDR, a strong supporter of trade unions, firmly rejected government bargaining: “The process of collective bargaining…cannot be transplanted into the public service.” Early labor leader Samuel Gompers refused to let police join the industrial union because, having sworn to serve the public, police would have a conflict of interest. As late as the 1950s, union leader George Meany stated unequivocally that it is “impossible to bargain collectively with the Government.”

But the strong tide of the 1960s rights revolution provided ample cover for government unions to get similar statutory powers as industrial unions. No one conceived back then that these powers would make government unmanageable. It was just considered a matter of “elementary justice” to treat them the same.

Government bargaining, however, is radically different from trade union bargaining:

A trade union must honor efficiency, or else the jobs are lost when the business moves out of town or fails. Government can’t go out of business or move, so public employee bargaining is aimed at creating deliberate inefficiencies to foster more jobs.Multi-hundred-page contracts that are designed for featherbedding and overtime excesses. Taxpayers must foot the bill.

Trade union bargaining is limited to dividing the pie of profit between capital and labor. There is no profit in government, so the scope of government bargaining has no defined limits. Again, the taxpayers must pay.

In trade union bargaining, it would be unlawful for management to collude with a complicit workers group. In government bargaining, overt collusion is how the game is played. In exchange for huge union campaign support, politicians agree to give unions control over public operations and pensions. As unions like to say, “we elect our own bosses.” At a rally with public unions, New Jersey’s then-Governor Jon Corzine called out that “We will fight for a fair contract!” Who was he going to fight? Collective bargaining with government unions is not a real negotiation. It’s a pay-off.

For fifty years, government union controls have gotten ever-tighter. Unlike all other interest groups, government unions have a binding contractual veto over how government operates, and are first in line for public resources. They keep it that way with preemptive political force. Stanford political scientist Terry Moe found that in 36 states teachers unions contributed more than all business groups combined.

The Disempowerment of Elected Executives

Newly-elected governors and mayors in most states quickly discover that they have no managerial control over schools, police, and other government operations. If an elected executive has the backbone to try to buck the union, and restore managerial powers when an agreement comes up for renegotiation, the executive in many states will find that unelected arbitrators have the final say.

Near-zero accountability makes its practically impossible to transform a lousy school, or an abusive police culture, because the supervisor can’t enforce good values and standards. No accountability also removes the mutual trust needed for any healthy organization. Why try hard, or go the extra mile, when others just go through the motions? The absence of accountability is like releasing a nerve gas into the agency or school.

Rigid work rules guarantee massive inefficiency. Basic services such as trash collection, and road and transit maintenance, cost two to three times what it would cost in the private sector. Need someone to help out or fill in? Sorry, not permitted. Need teachers to do remote teaching during the pandemic? There’s nothing about that in the agreement, so it must be negotiated.

No public purpose is served by union controls. Nor do union controls make government an attractive employer. Good candidates are repelled by toxic public cultures without energy or pride. Union controls serve only to transfer governing authority to union officials, who exercise that authority mainly to pad public employment and insulate government workers from supervisory judgments.

Public unions have turned public operations into a permanent spoils system: Unions have control over public operations and have insulated public employees from accountability, no matter how poorly they perform. That’s why democratically-elected leaders almost never fix what’s broken.\

All government employees should realize that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service. It has its distinct and insurmountable limitations when applied to public personnel management. The very nature and purposes of government make it impossible for administrative officials to represent fully or to bind the employer in mutual discussions with government employee organizations. The employer is the whole people, who speak by means of laws enacted by their representatives in Congress. Accordingly, administrative officials and employees alike are governed and guided, and in many instances restricted, by laws which establish policies, procedures, or rules in personnel matters. Particularly, I want to emphasize my conviction that militant tactics have no place in the functions of any organization of government employees. Upon employees in the Federal service rests the obligation to serve the whole people, whose interests and welfare require orderliness and continuity in the conduct of government activities. This obligation is paramount. Since their own services have to do with the functioning of the government, a strike of public employees manifests nothing less than an intent on their part to prevent or obstruct the operations of Government until their demands are satisfied. Such action, looking toward the paralysis of government by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, writer and civic leader, is author most recently of Not Accountable: Rethinking the Constitutionality of Public Employee Unions (Rodin Books, 2023). He is chairman of Common Good (commongood.org), a legal-and-regulatory-reform organization.

Read here Franklin Roosevelt’s views on public-employee unions.

Sam Pizzigati: Biden’s Roosveltian tax-the-rich plan

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

President Joe Biden has made no secret of his admiration for Franklin D. Roosevelt. The president proudly displays a portrait of FDR in the Oval Office.

More significantly, he’s announced the most ambitious plan since FDR’s New Deal for enhancing the well-being of working Americans while trimming the fortunes of America’s super rich. The president has promised to fund his big plans for infrastructure, jobs and education entirely with taxes on the top.

In fact, Biden’s new tax-the-rich plan is a good deal more Rooseveltian than the numbers, at first glance, might suggest.

In 1945, when FDR died in office, the nation’s most affluent faced a 94 percent tax on income over $200,000, a little more than $2.9 million in today’s dollars. The rates Biden has proposed come nowhere near those — they’d top out at just 39.6 percent of ordinary income over $400,000. That’s up only slightly from the current 37 percent.

But the gap between Biden’s plan and FDR shrinks big-time when we toss capital gains — the dollars the rich make buying and selling stocks and bonds, property, and other assets — into the picture.

In 1945, the nation’s deepest pockets paid a 25 percent tax on their capital-gains windfalls. Today’s rate tops off at 20 percent. For households making over $1 million in annual income, the Biden plan would raise the top capital- gains tax rate to 39.6 percent, the same top rate that applies to earnings from employment.

In other words, the Biden tax plan ends the most basic tax break for the ultra rich: the preferential treatment they get on the income from their wheeling and dealing. This would be a big deal. In 2019, 75 percent of the benefits from the capital-gains tax break went to America’s top 1 percent.

Dividends currently get the same preferential treatment. Americans making over $10 million in 2018 took in over half of their total incomes — 54 percent — via capital gains and dividends. If Congress adopts the Biden tax plan, the basic federal tax on that 54 percent would just about double, from 20 to 39.6 percent.

The Biden plan also totally eliminates the federal tax code’s open invitation to dynastic family wealth: the “step up” loophole. Under this notorious giveaway, any fabulously wealthy American sitting on unrealized capital gains can pass those gains onto heirs tax-free. The Biden plan short-circuits the simplest route to dynastic fortune.

Under Biden’s tax plan, new dynastic fortunes would have a much harder time taking root. Already existing dynastic fortunes, on the other hand, would still be with us. Biden — like FDR in his day — has not yet warmed to the idea of a wealth tax.

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren led a recent hearing highlighting the enormous contribution that even a 2 percent annual tax on grand fortunes could make. Among the insightful witnesses at the hearing: the 61-year-old Abigail Disney, the granddaughter of Roy Disney, the co-founder of the Disney empire with his brother Walt.

“I can tell you from personal experience,” Abigail Disney told senators, “that too much money is a morally corrosive thing — it gnaws away at your character… It warps your idea of how much you matter, and rather than make you free, it turns you fearful of losing what you have.”

Franklin Roosevelt understood that debilitating dynamic well enough to propose, in 1942, a 100 percent tax on annual income over what today would be about $400,000. Biden hasn’t ventured anywhere close to that level of daring. But he’s certainly come much further than anyone could reasonably have expected.

Sam Pizzigati is the Boston-based co-editor of Inequality.org and author of The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

NED chats weekly on WADK's 'Talk of the Town'

On most Thursdays at 9:30 a.m., Robert Whitcomb from New England Diary and GoLocal24.com will chat with Bruce Newbury on Mr. Newbury’s Talk of the Town show on WADK-A.M. (Newport).

Listen to it via broadcast or wadk.com

“The Fireside Chat,’’ bronze sculpture by George Segal in Room Two of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, Washington, D.C.. FDR ‘s fireside chats via radio were very popular among millions of Americans.

Glorious radio from 1941.

Llewellyn King: To revive America, fix the gig economy and bring back the WPA

McCoy Stadium, in Pawtucket, R.I., was a WPA project….

…and so was this field House and pump station in Scituate, Mass.

The assumption is that we’ll return to work when COVID-19 is contained, or we have adequate vaccines to deal with it.

That assumption is wrong. For many millions, maybe tens of millions, there will be no work to return to.

At root is a belief that the United States -- and much of the world -- will spring back as it did after the 2008 recession: battered but intact.

Fact is, we won’t. Many of today’s jobs won’t exist anymore. Many small businesses will simply, as the old phrase says, go to the wall. And large ones will be forced to downsize, abandoning marginal endeavors.

When we think of small businesses, we think of franchised shops or restaurants and manufacturers that sell through giants like Amazon and Walmart. But the shrinkage certainly goes further and deeper.

Retailing across the board is in trouble, from the big-box chains to the mom-and-pop clothing stores. The big retailers were reeling well before the coronavirus crisis. Neiman Marcus, an iconic luxury retailer, has filed for bankruptcy. All are hurt, some so much so – especially malls -- that they may be looking to a bleak future.

The supply chain will drive some companies out of business. Small manufacturers may find that their raw material suppliers are no longer there or that the supply chain has collapsed – for example, the clothing manufacturer who can’t get cloth from Italy, dye from Japan or fastenings from China. Over the years, supply chains have become notoriously tight as efficiency has become a business byword.

Some will adapt, some won’t be able to do so. A record 26.5 million Americans have sought unemployment benefits over the past five weeks. Official unemployment numbers have always been on the low side as there’s no way of counting those who’ve given up, those who work in the gray economy, and those who for other reasons, like fear of officialdom or lack of computer skills, haven’t applied for unemployment benefits.

To deal with this situation the government will have to be nimble and imaginative. The idea that the economy will bounce back in a classic V-shape is likely to prove illusory.

The natural response will be for more government handouts. But that won’t solve the systemic problem and will introduce a problem of its own: The dole will build up dependence.

I see two solutions, both of which will require political imagination and fortitude. First, boost the gig economy (contract and casual work) and provide gig workers with the basic structure that formal workers enjoy: Social Security, collective health insurance, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation. The gig worker, whether cutting lawns, creating Web sites, or driving for a ride-sharing company, should be brought into the established employment fold; they’re employed but differently.

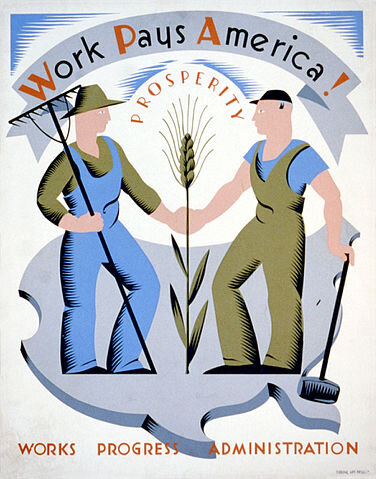

Second, a new Works Progress Administration (WPA) should be created using government and private funding and concentrating on the infrastructure. The WPA, created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, ended up employing 8.5 million Americans, out of a total population of 127.3 million, in projects ranging from mural painting to bridge building. Its impact for good was enormous. It fed the hungry with dignity, not the soup kitchen and bread line, and gave America a gift that has kept on giving to this day.

Jarrod Hazelton, a Rhode Island-based economist who’s researched the WPA, says the agency gave us 280,000 miles of repaired roads, almost 30,000 new and repaired bridges, 600 new airports, thousands of new schools, innumerable arts programs, and 24 million planted trees. It also enabled workers to acquire skills and escape the dead-end jobs they’d lost. It was one of the most successful public-private programs in all of history.

As the sea levels rise and the climate deteriorates, we’ll need a WPA, tied in with the Army Corps of Engineers, to help the nation flourish in the decades of challenge ahead. The original was created by FDR with a simple executive order.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Robert Whitcomb: Too much wind for too much wood on Sept. 21, 1938

“The roaring wind toppled forests in every New England state, with New Hampshire and Massachusetts (east of the eye of the storm) hit particularly hard. The path of destruction spanned ninety miles across....’’ And “70 percent or more of the toppled timber was Pinus strobus – eastern white pine’’ – the most valuable (and vulnerable) tree crop in New England because of its height, straightness and its many uses, from lumber to make houses, to furniture to cheap shipping boxe

(Original review published by The Weekly Standard)

When I was a boy living in coastal Massachusetts I frequently heard stories about the great hurricane that crashed into Long Island and New England on Sept. 21, 1938. Most of the people who described it to me – my father and some of his friends -- were only in their thirties and early forties when they told me about it, and had very vivid stories, especially after a few drinks."

What the 1906 earthquake is to San Francisco, the 1871 fire is to Chicago and Hurricane Katrina is to New Orleans, the ’38 Hurricane (aka “The Long Island Express’’) is to New England and Long Island.

Given the scale of the catastrophe in one of the most populous and richest parts of the country, the ’38 Hurricane at first got surprisingly little attention from the rest of the country because attention was riveted on the Munich Crisis; many assumed that war was about to break out in Europe; of course, that wouldn’t be for another year.

The storm killed around 700 people and destroyed many buildings, bridges and miles of road. Its tidal surge altered long stretches of the southern New England and Long Island coasts.

Stephen Long clearly and dramatically, and sometimes with droll humor, details the mayhem produced by torrential rain followed by winds that gusted to nearly 200 miles an hour on Blue Hill, south of Boston. He serves up a mix of regional history, meteorology, botany, ecology, politics, economics -- allseasoned with anecdotes.

But his book is mostly about the trees that the storm took down, especially in New England’s large and well-established second-growth forests and “the pastoral combination of farm field and forest {that} adorned’’ the region, interspersed by villages with steepled white churches. That’s the (unrepresentative) scene that many tourists most associate with the region. The storm’s massive blowdowns (including of steeples) altered the views in many places.

As a boy, I saw evidence of this damage in the woods next to our house, where there were numerous pits where the roots of uprooted trees had been. From the pits’ shape you could tell which direction the strongest wind came – southeast, at more than 100 miles an hour. And there were still many gaps in the woods where tall trees had once stood.

Mr. Long, founder and former editor of Northern Woodlands magazine, focuses on the ecological, economic and sociological effects of the storm’s destruction of mature trees in a wide swath of New England.

“The roaring wind toppled forests in every New England state, with New Hampshire and Massachusetts (east of the eye of the storm) hit particularly hard. The path of destruction spanned ninety miles across....’’ And “70 percent or more of the toppled timber was Pinus strobus – eastern white pine’’ – the most valuable (and vulnerable) tree crop in New England because of its height, straightness and its many uses, from lumber to make houses, to furniture to cheap shipping boxes. (Mr. Long describes how mighty New England’s cheap-pine-box industry was before heavy-duty cardboard and plastic took its place.)

All this devastated many landowners, already brought low by the Great Depression, who depended on pine sales from their wood lots to make ends meet.

Also torn up were many maple-tree stands, the sap from which provided a lot of extra income to New England farmers and other landowners.

Mr. Long writes very accessibly about why certain trees sustained far more damage than others -- e.g., “The taller the tree the longer the lever and the greater the force it can exert on the ground where it’s anchored.’’ Trees on southeast-facing slopes were particularly vulnerable.

Enter the New Deal, in an example of what perhaps only government can do: Clean up damage from natural disasters that extends over many square miles. Much praise was due the U.S. Forest Service, as well as Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, in responding to a disaster as huge as the ’38 Hurricane.

The first imperative, state and federal officials and an anxious public thought, was to reduce the chances of massive forest fires from the downed and thus drying trees and branches. Indeed, some of the forests were closed to the public for long stretches after the hurricane for fear of fire. That the hurricane had made many of the fire-watch towers inaccessible -- roads were blocked by fallen trees – made it that much scarier.

And so, Mr. Long explains, federal officials, led by the U.S. Forest Service, pulled together the resources of various organizations but especially thousands of otherwise unemployed men working for the CCC (young men) and the WPA (which had older men too). They opened roads and helped clean out much of the combustible debris left on the ground by the hurricane.

The Roosevelt administration pushed the project. Mr. Long describes “the WPA’s own portrayal of its hurricane relief efforts, as seen in an eleven-minute film….Shock Troops of Disaster bears a striking resemblance to wartime newsreels, depicting feverish activity accompanied by charged music and stentorian narration. Referring to the WPA, the narrator described it in this way: ‘Manpower, turning from regular public improvements and services into the breach in times of dire need.’’’

But what to do with the fallen timber taken out of the woods, which could flood the market and lower the already low price of the wood? To address this issue, the government invaded the private market with a vengeance.

Mr. Long explains: “The Forest Service saw the need for a stabilizing influence on the price of logs and the flow of lumber to the market….{so it} put the power of the federal government to work’’ by establishing “a fair price for logs,’’ and buying up all it could and then gradually selling it as “demand required. At the heart of this reasoning was that the purchasing program would allow thousands of local landowners to realize a decent return from what could have been a nearly total economic loss.’’

“The total cost of the salvage program was $16,269,000’’ {in dollars of the time}, of which 92 percent was recovered by the government. It seems doubtful that such market intervention will happen after the next big hurricane blows through. But then, FDR & Co. saw the hurricane response as another way of fighting the Depression.

The cleanup showed just how good Americans, via a collaboration of the private and public sectors, can be at addressing an emergency – as they were soon to prove after Pearl Harbor. And a lot of that hurricane wood was used in war-related products and then in the post-war building boom.

Meanwhile, with the continuing disappearance of farmland, New England is now more forested than at any time in 200 years. Some year, the Northeast will again have a record surplus of lumber on the ground after another huge hurricane. We may then long for a CCC and a WPA.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is overseer of newenglanddiary.com.