From The Conversation

MEDFORD, Mass.

The past decade and a half has seen upheaval across the globe. The 2008 financial crisis and its fallout, the COVID-19 pandemic and major regional conflicts in Sudan, the Middle East, Ukraine and elsewhere have left residual uncertainty. Added to this is a tense, growing rivalry between the U.S. and its perceived opponents, particularly China.

In response to these jarring times, commentators have often reached for the easy analogy of the post-1945 era to explain geopolitics. The world is, we are told repeatedly, entering a “new Cold War.”

But as a historian of the U.S.’s place in the world, these references to a conflict that pitted the West in a decades-long ideological battle with the Soviet Union and its allies – and the ripples the Cold War had around the globe – are a flawed lens to view today’s events. To a critical eye, the world looks less like the structured competition of that Cold War and more like the grinding collapse of world order that took place during the 1930s.

The ‘low dishonest decade’

In 1939, the poet W.H. Auden referred to the previous 10 years as the “low dishonest decade” – a time that bred uncertainty and conflict.

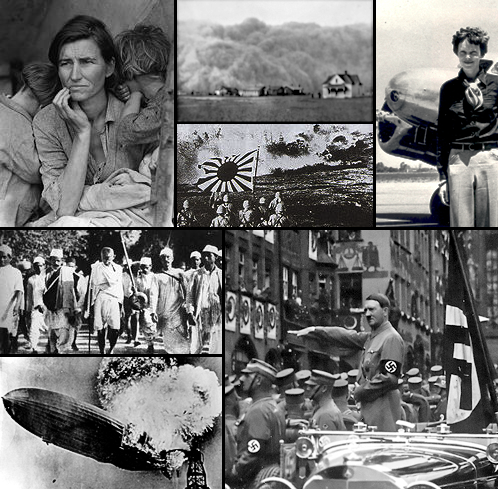

From the vantage of almost a century of hindsight, the period from the Wall Street Crash of 1929 to the onset of World War II can be distorted by loaded terms like “isolationism” or “appeasement.” The decade is cast as a morality play about the rise of figures like Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini and simple tales of aggression appeased.

But the era was much more complicated. Powerful forces in the 1930s reshaped economies, societies and political beliefs. Understanding these dynamics can provide clarity for the confounding events of recent years.

Greater and lesser depressions

The Great Depression defined the 1930s across the world. It was not, as it is often remembered, simply the stock market crash of 1929. That was merely an overture to a large-scale unraveling of the world economy that lasted a painfully long time.

Persistent economic problems impacted economies and individuals from Minneapolis to Mumbai, India, and wrought profound cultural, social and, ultimately, political changes. Meanwhile, the length of the Great Depression and its resistance to standard solutions – such as simply letting market forces “purge the rot” of a massive crisis – discredited the laissez faire approach to economics and the liberal capitalist states that supported it.

The “Lesser Depression” that followed the 2008 financial crisis produced something similar – throwing international and domestic economies into chaos, making billions insecure and discrediting a liberal globalization that had ruled since the 1990s.

In both the greater and lesser depressions, people around the world had their lives upended and, finding established ideas, elites and institutions wanting, turned to more radical and extreme voices.

The 1929 stock market crash resulted in a loss of trust for financial institutions. AP Photo

It wasn’t just Wall Street that crashed; for many, the crisis undercut the ideology driving the U.S. and many parts of the world: liberalism. In the 1930s, this skepticism bred questions of whether democracy and capitalism, already beset with contradictions in the form of discrimination, racism and empire, were suited for the demands of the modern world. Over the past decade, we have similarly seen voters turn to authoritarian-leaning populists in countries around the world.

American essayist Edmund Wilson lamented in 1931: “We have lost … not merely our way in the economic labyrinth but our conviction of the value of what we are doing.” Writers in major magazines accounted for “why liberalism is bankrupt.”

Today, figures on the left and right can similarly share in a view articulated by conservative political scientist Patrick Deneen in his book, “Why Liberalism Failed.”

Ill winds

Liberalism – an ideology broadly based on individual freedoms and rule of law as well as a faith in private property and the free market – was touted by its backers as a way to bring democratization and economic prosperity to the world. But recently, liberal “globalization” has hit the skids.

The Great Depression had a similar effect. The optimism of the 1920s – a period some called the “first wave” of democratization – collapsed as countries from Japan to Poland established populist, authoritarian governments.

A Japanese military parade on the second anniversary of the Sino-Japanese conflict in Manchuria. Imagno/Getty Images

The rise today of figures like Hungary’s Victor Orban, Vladimir Putin in Russia, and China’s Xi Jinping remind historians of the continuing appeal of authoritarianism in moments of uncertainty.

Both eras share a growing fragmentation in the world economy in which countries, including the U.S., tried to staunch economic bleeding by raising tariffs to protect domestic industries.

Economic nationalism, although hotly debated and opposed, became a dominant force globally in the 1930s. This is mirrored by recent appeals of protectionist policies in many countries, including the U.S.

A world of grievance

While the Great Depression sparked a “New Deal” in the United States where the government took on new roles in the economy and society, elsewhere people burned by the implosion of a liberal world economy saw the rise of regimes that placed enormous power in the hands of the central government.

The appeal today of China’s model of authoritarian economic growth, and the image of the strongman embodied by Orban, Putin and others – not only in parts of the “Global South” but also in parts of the West – echoes the 1930s.

The Depression intensified a set of what were called “totalitarian” ideologies: fascism in Italy, communism in Russia, militarism in Japan and, above all, Nazism in Germany.

Importantly, it gave these systems a level of legitimacy in the eyes of many around the world, particularly when compared to doddering liberal governments that seemed unable to offer answers to the crises.

Some of these totalitarian regimes had preexisting grievances with the world established after World War I. And, after the failure of a global order based on liberal principles to deliver stability, they set out to reshape it on their own terms.

Observers today may express shock at the return of large-scale war and the challenge it poses to global stability. But it has a distinct parallel to the Depression years.

Early in the 1930s, countries like Japan moved to revise the world system through force – hence the reason such nations were known as “revisionist.” Slicing off pieces of China, specifically Manchuria in 1931, was met — not unlike Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014 — with little more than nonrecognition from the Western democracies.

As the decade progressed, open military aggression spread. China became a bellwether as its anti-imperial war for self-preservation against Japan was haltingly supported by other powers. Ukrainians today might well understand this parallel.

Ethiopia, Spain, Czechoslovakia and eventually Poland became targets for “revisionist” states using military aggression, or the threat of it, to reshape the international order in their own image.

Ironically, by the end of the 1930s, many living through those crisis years saw their own “cold war” against the regimes and methods of states like Nazi Germany. They used those very words to describe the breakdown of normal international affairs into a scrum of constant, sometimes violent, competition. French observers described a period of “no peace, no war” or a “demi guerre.”

Figures at the time understood that it was less an ongoing competition than a crucible for norms and relationships being forged anew. Their words echo in the sentiments of those who see today the forging of a new multipolar world and the rise of regional powers looking to expand their own local influences.

Taking the reins

It is sobering to compare our current moment with one in the past whose terminus was global war.

Historical parallels are never perfect, but they do invite us to reconsider our present. Our future neither has to be a reprise of the “hot war” that concluded the 1930s, nor the Cold War that followed.

The rising power and capabilities of countries like Brazil, India and other regional powers remind one that historical actors evolve and change. However, acknowledging that our own era, like the 1930s, is a complicated multipolar period, buffeted by serious crises, allows us to see that tectonic forces are again reshaping many basic relationships. Comprehending this offers us a chance to rein in forces that in another time led to catastrophe.

David Ekbladh is a professor of history at Tufts University, in Medford, Mass.

Disclosure statement

David Ekbladh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

History