Let the river do the heating

Spring on the Charles River Esplanade

— Photo by Ingfbruno

#heat pump #Charles River

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

Cleaner-energy progress continues in unexpected ways. I recently learned this:

Vicinity Energy, based in Boston, is partnering with Germany’s MAN Energy Solutions to collaborate in developing heat-pump systems for steam generation using water from the Charles River. Vicinity says it will install such an industrial-scale complex at its Kendall Station facility (in Cambridge) by 2026.

A heat pump extracts heat from a source, such as the air, geothermal energy in the ground or nearby sources of water or waste heat from a factory. It then amplifies and transfers the heat to where it is needed.

The giant heat-pump complex will generate steam with which to heat many large buildings in Cambridge and Boston, which could save owners and renters a lot of money.

Vicinity says that this will be the largest such facility in the U.S. and “will be powered by renewable electricity to safely and efficiently harvest energy from the Charles River, returning it at a lower temperature.’’ The idea is to renewably harvest thermal energy from rivers and oceans, which are warming because of climate change, thus helping decarbonize localities, especially cities.

How about something like this in Rhode Island? Lots of water available.

Hit these links:

Water-source heat-exchanger being installed in England

Looking at 'Water through the lens of climate change'

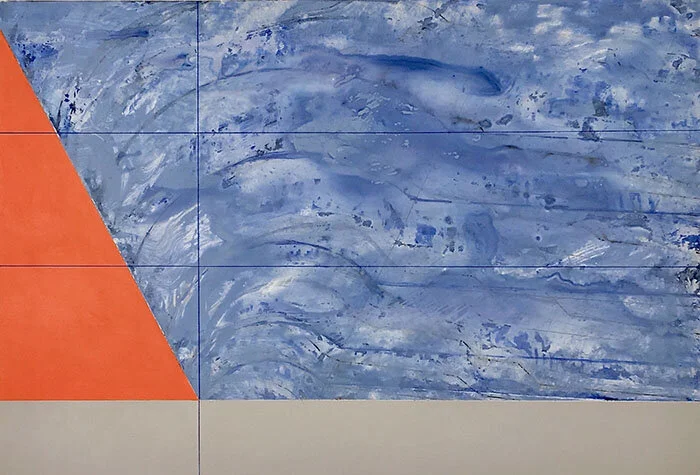

“Watermark” (acrylic on Yupo), by Greater Boston-based Patty Stone, in her show “Watermark’’, at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Sept. 1-26. Many of her paintings have been inspired by her close observation of the Charles River.

The gallery says:

“Patty Stone investigates the movement of water through the lens of climate change in a new series of abstract paintings and works on paper. Watermark juxtaposes a fluid paint surface against geometric shapes and lines of measurement suggesting rising tides or changing shorelines.’’

The Charles River at the Medfield-Millis (Mass.) town line

Hot colors, cold water

“Lake Sky” (oil on canvas), by Kate Graham Heyd, in Galatea Fine Art’s (Boston) August show, “New England Collective XI.’’ She lives in Hopkinton, Mass., which is most famous as the starting point of the Boston Marathon and of the Charles River.

And I learned to sail there

The Community Boating clubhouse on the Charles River in Boston

“Boston was a great city to grow up in, and it probably still is. We were surrounded by two very important elements: academia and the arts. I was surrounded by theater, music, dance, museums. And I learned how to sail on the Charles River. So I had a great childhood in Boston. It was wonderful.” –

Leonard Nimoy ( 1931-2015), American actor, filmmaker photographer, author, singer and songwriter best known for playing Spock in the Star Trek franchise

To delight them downstream

The Charles River at the Medfield-Millis (Mass.) town live

Dark brown is the river,

Golden is the sand.

It flows along for ever,

With trees on either hand.

Green leaves a-floating,

Castles of the foam,

Boats of mine a-boating -

Where will all come home?

On goes the river

And out past the mill,

Away down the valley,

Away down the hill.

Away down the river,

A hundred miles or more,

Other little children

Shall bring my boats ashore.

— “Where Go the Boats,’’ by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894), Scottish novelist, poet and travel writer

Satellite image of the Connecticut River depositing silt into Long Island Sound

New England a biotech power against COVID-19

Kendall Square in Cambridge, as seen from across the Charles River in Boston. It’s the epicenter of the New England biotech sector.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The economy may or may not recover soon from the pandemic, but in any case New England’s role as a world center for health-related science will probably continue to grow. Indeed, the search for a vaccine for COVID-19 and new treatments for that and other illnesses, old and new, will tend to accelerate this growth. It’s a bit macabre to say so, but New England’s economy could benefit from COVID-19. Researchers in the region are hard at work trying to develop vaccines and treatments against the disease.

That’s not to minimize the damage done to other important regional sectors, especially higher education, and of course the region’s universities do a great deal of life-sciences research. It’s complicated.

Just look at the plan by life-sciences company IQHQ to buy the 26-acre headquarters and campus of GCP Applied Technologies, in North Cambridge, Mass., for $125 million. GCP makes chemicals and construction materials.

The Boston Globe reports that the “once light-industrial area is rapidly transforming into a hub for labs and housing. It’s one of several areas around the region that are drawing tech and life science companies looking for cheaper or roomier alternatives to {Cambridge’s} Kendall Square.’’

To read The Globe’s story, please hit this link.

This is, of course, the sort of business that Rhode Island is trying to get, especially for the land freed up in downtown Providence by the moving of Route 195.

'Treading on shadow'

Looking down the Charles toward Boston

“Taking the well-worn path in the mind through dusk encroaches

upon the mind, taking back alleys careful step by step

past parked cars and trash containers, three blocks to the concrete ramp

of the footbridge spanning the highway with its rivering, four-lane

unstaunchable traffic, treading on shadow and slant broken light

my mother finds her way.’’

— From “Island in the Charles ,’’ by Rosanna Warren

You can still swim in the Charles

View of the Charles River from the Boston University Bridge.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

BOSTON

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently gave a grade of B for water quality last year in the Charles River. This is a slight reduction from the B+ grade awarded for water quality in the river in 2015.

EPA and state and local partners have worked to improve water quality in the Charles River for more than two decades. This is the 22nd year EPA has issued a Charles River Report Card. The 2016 grade of B reflects EPA analysis of bacterial contamination in water samples taken monthly from the lower Charles River by the Charles River Watershed Association (CRWA) at 10 sampling stations between Watertown and Boston.

In 2016, the Charles River met Massachusetts's bacterial water-quality standards for boating 86 percent of the time and for swimming 55 percent of the time. The grade is determined according to the following criteria:

A: Almost always met standards for boating and swimming

B: Met standards for almost all boating and some swimming

C: Met standards for some boating and some swimming

D: Met standards for some boating but no swimming

F: Didn’t meet standards for boating or swimming

The grade is also based on a comparison to previous years’ grades and whether the water quality has improved. The slightly lower grade for 2016 is likely related to the fact that seven out of 10 sample events occurred during or immediately after a rain event, despite the overall drought conditions that occurred throughout the region during most of 2016, according to EPA.

The lower Charles River has improved dramatically from the launch of EPA’s Charles River Initiative in 1995, when the river received a D for meeting boating standards only 39 percent of the time and swimming standards just 19 percent of the time. Improvements are due to a significant reduction in the amount of sewage discharged into the river during the past 20 years from combined sewer overflows and illicit discharges through storm drains. Illicit discharges often consist of cracked and leaking sewer pipes or improper sewer connections to the storm-drain system.

For the third year, EPA has launched a water-quality monitoring buoy in front of the Museum of Science in the Charles River Lower Basin. This buoy measures water quality in near real time, and the data can be viewed on EPA’s Charles River Web site and viewed as part of an exhibit on the Charles River in the Museum of Science.

The 2016 calendar year saw further expansion on the public’s enjoyment of the long-term trend of improved water quality in the Charles River, illustrated by some 140 swimmers competing in the Charles River Swim, a mile swim held in June, and the release of a study for a permanent swimming area near the entrance to the Charles at North Point Park.

Aside from illicit discharges, stormwater containing phosphorus, and the algae it produces, are some of the major pollution problems remaining. A major load of phosphorus comes from fertilizer and runoff from impervious surfaces such as roads and rooftops.

Celebrating water protection in N.E.

A stretch of the Connecticut River in western Massachusetts.

BOSTON

At a spot overlooking Boston Harbor, once choked with toxic pollution but now home to some of the cleanest urban beaches in the United States, advocates gathered July 1 to thank the Obama administration for closing loopholes in the Clean Water Act that previously left more than half of Massachusetts’s streams at risk of pollution.

“We’ve made so much progress in cleaning up our waterways, and we can’t afford to turn back the clock,” said Ben Hellerstein, state director for Environment Massachusetts. “The EPA’s Clean Water Rule will make a big difference in protecting Boston Harbor, the Charles River and all of the waterways we love.”

The Clean Water Rule, finalized in late May, clarifies federal protections for waterways following confusion over jurisdiction created by Supreme Court decisions in 2001 and 2006. It restores Clean Water Act protections to thousands of miles of streams that feed into waterways that provide drinking water for millions.

“In New England, protecting our water is more important than ever, especially as we work to adapt to climate-change impacts such as sea-level rise and stronger storms,” Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Regional Administrator Curt Spalding said. “Protecting the most vulnerable streams and wetlands — a drinking-water resource for one in three Americans — helps our communities, and this rule provides clarity for businesses and industry without creating new permitting requirements.”

Before the Clean Water Rule became law, small streams, headwaters and certain wetlands were in a perilous legal limbo, allowing polluters and developers to dump into them or destroy them in many cases without a permit. In a four-year period following the rule’s creation, the EPA had to drop more than 1,500 cases against polluters, according to one analysis by The New York Times.

Prior to the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, Massachusetts waterways suffered from decades of pollution and neglect. As late as the 1980s, untreated sewage was regularly dumped into Boston Harbor, and high concentrations of industrial pollutants posed a public-health risk.

The Clean Water Act prompted a major cleanup of the harbor. Today, Boston boasts some of the cleanest urban beaches in the nation, and wildlife habitat has significantly improved, according to Environment Massachusetts.

Advocates pointed out that the Clean Water Act has enabled similar improvements in water quality in many of the state’s most iconic waterways, from the Charles River to the Connecticut River.

Despite broad public support for clean-water protections, polluting industries and some members of Congress are fighting to block implementation of the Clean Water Rule. In recent weeks, congressional committees have approved multiple bills aimed at rolling back the Clean Water Rule.