Thoughts on summer as it ebbs (?)

“Summer Dreaming” (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb

(The trick is to get across the Cape Cod Canal bridges.)

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Like many GoLocal readers, I’ve spent much of my life near beaches. To me, they’ve mostly become places to simply walk on, especially in the off-season, to clear one’s head and maybe spot some interesting wildlife, dead or alive.

Where I lived during much of my youth, in Cohasset, on Massachusetts Bay, there’s a mix of sandy gray beaches and very uncomfortable stony strands (recalling Maine) and summertime water that, at least back then, was sometimes much too cold to comfortably swim in, especially on the hottest days, when the southwest wind blew the warm surface water seaward. I came to think that these beaches were mostly good for clambakes, fireworks and letting our dogs run on them. (No enforced leash laws in our town then.) All too often, bunker oil dumped from ships going into Boston Harbor (see below) would coat the beaches, which were also popular teen drinking places at night.

In West Falmouth, on Buzzards Bay, where our paternal grandparents lived, it was quite different, with the usual sou’wester pushing the 77-degree surface water (already fairly warm because of eddies from the Gulf Stream and the shallowness of the bay) toward the soft beach, which included a private club with a simple gray-shingled building that had to be rebuilt after major hurricanes and a tennis court that had to be frequently swept of the sand that blew in from the sand dunes that bordered it.

It had/has a swimming dock that was a centerpiece of kids’ activities there. (There were also some board games in the clubhouse for rainy days and some mildewed books, heavy on potboilers.) Do they worry about sharks swimming near the beach now? We never did.

I never much enjoyed sitting or lying on beaches, with the sand getting into your hair, eyes, swimming suit, sandwiches and potato salad. And no matter how much you rinsed your feet, the grains would stick in your sneakers and end up on the floor in the car and back home. And then there were the flying rats known as seagulls, which would swoop down and steal your lunch and maybe leave a deposit on your head. And sometimes, layers of biting-insect-luring seaweed would cover the lower beach.

Still, the sound of the waves was soporific and being able to look at a far horizon, with its many sailboats, helped put troubles into perspective. And there’s no doubt that being in the sun felt good (for a while), though at the risk of burns and skin cancer (which I’ve had plenty of). Few people thought about that more than 50 years ago. I remember my parents saying “You sure look healthy!’’ when looking at my red face.

The best part of that beach to me became the porch, where I’d read for hours sitting in a rocking chair and taking swigs of the Orange Crush I bought at the club’s little snack bar. There in the shade and a cooling breeze I’d enjoy the views and sounds of the beach without much of the mess, though on a gusty day sometimes sands would blow in there, too.

Does going to beaches tend to make people more environmentalist? We now occasionally use, for a modest annual fee, a beautiful beach, along a cattle farm and tidal river, in South Dartmouth, Mass. It has no facilities except a couple of Port-a-Johns, which, helpfully, tends to discourage day-long visits.

Most importantly, it’s set up in part as a nature preserve – the threatened Piping Plovers, etc. This role tends to make members talk about conservation a lot as they gaze at the low hills of the Elizabeth Islands across usually hazy Buzzards Bay.

Then there were the French beaches where, when we lived and worked in that nation, we were surprised/titillated by how much Western traditions governing public nudity have changed in some places and how waiters would bring food and drinks to you right onto the beach.

We found the most ominous beaches in Florida, with the poisonous Portuguese Man O’War with their lovely blue balloon sails that you wanted to pop, the certainty that there were indeed sharks off the beach commuting up the Gulf Stream, and the brown, wrinkled and irascible retirees. Worse, though mostly on the Gulf of Mexico side, were the toxic red tides, which polluted the air several blocks inland.

We always had small boats – rowboats, small sailboats, up to 17 feet long, even a canoe. We had an outboard motor or two to stick on sterns when needed, but these could be pesky to get going. The boats were practical possessions since we lived up a hill from a harbor. (The canoe was used on a nearby mill pond.)

Before fiberglass, the boats meant a lot of springtime work sanding and caulking the wooden bottoms before applying anti-fouling copper paint. Then we had to carefully maneuver a trailer to launch the sailboats in June and then reverse the process in late September. As the years rolled by, this got tedious.

The channel from the harbor out to the bay, which at Cohasset was really more the open ocean, was narrow, with ever shifting sandy shoals on one side and mussel beds (where we got our bait) on the other and sometimes was quite laborious to get through by sail.

In mid-summer heat waves you had to voyage out at least a mile, to the vicinity of the famous Minot’s Light, to get the real air-cooling effect. You’d hope that ships hadn’t recently dumped a lot of bunker oil, which could cover miles of water and give off a very noxious smell. Thank God for the EPA!

Then back to the small harbor, which became increasingly crowded with large and small pleasure boats over the years, I suppose because of growing local affluence as this small town became an all-out suburb. No longer were lobster and other commercial fishing boats numerous.

It was soothing to go sailing alone, which, if the breeze were a steady 10 to 20 knots, would put you in a ruminative mood. Sometimes you’d throw out an anchor and fish for mackerel, hoping that you wouldn’t get a dogfish instead.

It was also often fun to have small parties on the boats, except when the wind and social energy flagged and there you were – sometimes trapped for hours – in a small cockpit. Eventually, the claustrophobia might force you to use the outboard to motor in.

I still like to go out on boats once or twice a summer if I have a pretty good idea of when I’ll get back to shore. But with the expense and time involved in owning a boat, I’d just as soon have it someone else’s.

xxx

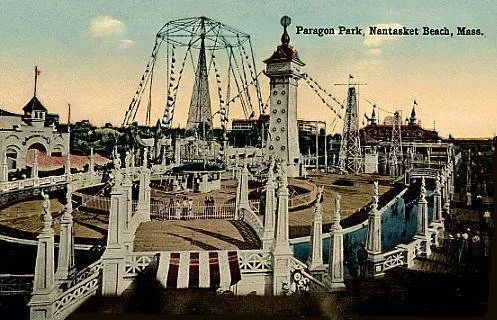

Paragon Park, in Hull, in 1914

There was a now long-gone amusement park, called Paragon Park, along a rather polluted strand called Nantasket Beach, in Hull, Mass., that we’d be taken to about once a year, often around my birthday. There was a lethal roller-coaster, a fun house with sloppily made monsters and, my favorite, something called “The Rotor.” This giant infernal cylindrical device, into which you’d walk, would spin you around at such velocity that you’d be stuck to the walls. (Sounds like astronaut training.)

Inevitably, a kid would get sick and upchuck the junk food (cotton candy, popcorn and hot dogs, etc., of indeterminate origin). Perhaps for the same reason that I very rarely get seasick, I didn’t suffer this misfortune.

Then there were the games (with prizes “Made in Japan,’’ back when that phrase meant cheap instead of high quality), which usually involved throwing a ball at something as a bored attendant (usually an older teen doing this as a summer job) looked on with a frown or a rictus smile.

Paragon Park was notably garish but, especially when you’re young, “kitsch is everything you really like,’’ in the immortal words of our late musician friend with the wonderful name of Page Farnsworth Grubb, who ended his years in Iowa. Despite what you might think from his name, he was about the least pretentious person you could meet. By the way, if you want pretentious, look at the marketing for “The Preserve,” in Richmond, R.I.

'Too damn cold'

Old Orchard Beach in 1914

“{It’s) the only fault I have with Maine, the water is just too damn cold.’’

— Arthur Griffin, in New England: The Four Seasons (1980)

Editor’s Note: But the Gulf of Maine is now one of the world’s fastest-warming bodies of salt water. Still, the water on the south coast of New England (particularly Buzzards Bay) can be as much as 20 degrees warmer than the Gulf of Maine in the summer.

Saving coastal farm is biggest land-conservation project along Buzzards Bay

This 115-acre farm was one of the last undeveloped and unprotected areas of coastal farmland on Buzzards Bay. (Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust)

By ecoRI News staff (ecori.org)

DARTMOUTH, Mass.

The Buzzards Bay Coalition and its partners, the Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust and Round the Bend Farm, recently celebrated the permanent protection of 115-acre Ocean View Farm on Allens Pond, the largest land-conservation project ever completed along the coast of Buzzards Bay.

Completed this past summer, the protection of Ocean View Farm was an $8.1 million component of a larger land-conservation initiative on Allens Pond, which has been recognized as one of southern New England’s most significant coastal habitats. The larger Allens Pond Conservation Completion Project is expected to protect an additional 100 neighboring acres of forests, wetlands and active farmland.

“Visionary landowners and conservation organizations have worked together over decades to protect and preserve Allens Pond,” Buzzards Bay Coalition president Mark Rasmussen said. “But the fate of one landholding on the pond still threatened this landscape’s extraordinary agricultural and natural values. Ocean View Farm narrowly missed being covered with new homes, roads, and septic systems several times in recent years. With the support of so many levels of government and generous neighbors coming together to raise the money needed to save this place, this jewel of Buzzards Bay will now be protected forever.”

Ocean View Farm was one of the last undeveloped and unprotected areas of coastal farmland on Buzzards Bay.

“Ocean View Farm had long been one of the top conservation priorities in the town of Dartmouth due to its large size, prime location, outstanding agricultural land and abundant natural resources,” Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust (DNRT) executive director Dexter Mead said. “Without the remarkable support of so many public and private donors, we never could have accomplished our goal.”

Round the Bend Farm will put the deep, rich soils on the northern 55 acres to work as an all-organic farm, and DNRT will eventually open a new public trail on a 60-acre waterfront portion of Ocean View Farm.

“Our mission is to create a restorative community. The newly acquired 55 acres will bring our farm to 94 acres; expand our realm into focused, sustainable food production; and increase our impact on providing nutritious food for people of all socioeconomic demographics,” said Desa Van Laarhoven, executive director of Round the Bend Farm. “On this land, we intend to cultivate a community that is diverse in race, gender and culture. Our vision is opening this land to a new generation of farmers, specifically targeting women and people of color, those who have historically worked the land but have been locked out of long-term leasing and ownership.”

The Buzzards Bay Coalition holds a permanent conservation restriction on the northern portion of the farm and co-holds a conservation restriction on the southern portion, along with the Dartmouth Conservation Commission, ensuring that this land will never be developed.

During the past year, the coalition spearheaded assembly of a patchwork of federal, state and local government funding and private fundraising to protect this land for future generations. The U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded the project nearly $2 million, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service provided $1.1 million.

“Public-private partnerships are essential in protecting the nature of our nation’s coastal wetlands,” said Mark Cookson, regional coastal program coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “These marshes provide us with clean water, and are important areas for wildlife including the federally endangered roseate tern.”

Last fall, Dartmouth residents voted to contribute $600,000 in Community Preservation Act funding to save 60 acres of Ocean View Farm. The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation also provided the project with a $400,000 grant.

The project was also supported by more than $2.92 million in private donations from 365 individuals and families. The Bromley Charitable Trust also contributed $2 million to the project in support of Round the Bend Farm. The Buzzards Bay Coalition and DNRT are seeking $70,000 in private donations to complete the project.

Buzzards Bay most perilous for a hurricane surge

During the tidal surge that accompanied the Sept. 21, 1938 hurricane that ravaged Long Island and much of New England. The southeast to southwest winds on the east side of the storm pushed particularly high surges up Narragansett and Buzzards bays.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

We in southern New England have had some famous hurricanes, although they’re usually different from those Down South. (They tend to be less intense, wider and to move forward faster.) So what are the questions/lessons from Harvey’s assault on Houston?

The most difficult lesson is that far too much building has been happening in flood zones, which includes much of Houston. And assuming that climate scientists are right, the results of overbuilding will get worse. Houston and Texas in general has lax (in comparison to, for example, the Northeast and California) building codes and in some places, most notably Houston, little zoning.

This has led to massive paving and building over of flood-vulnerable land, which has worsened flooding as water has poured from pavement and other hard surfaces into overburdened bayous. Marshlands, woods and meadows absorb water and thus mitigate the effects of area flooding. In Greater Houston, much of these giant sponges have been destroyed to make way for parking lots, malls and subdivisionsin the nearly uncontrolled development that Texas is famous for.

Of course people like to live near water. Aided by the much-in-need-of reform Federal Flood Insurance Program, individuals and developers have built too close to the sea and rivers – with an irresponsibility partly subsidized by taxpayers. Seas continue to rise and rainfall events are becoming more extreme. A lot of this indirect waterfront building subsidy turns out to be welfare for the rich, who can afford the high purchase price of waterfront property.

In some places, though, fear of flooding is leading even affluent folks to move to higher ground from homes right along the shore. This has even led to gentrification in, for example, previously unfashionable, higher parts of Miami. Let’s hope that this also happens more in inland jurisdictions open to massive freshwater flooding.

It’s unlikely that the Trump administration will take on developers (after all, Trump continues to be one, even in office) and push for gradual moves to keep new building away from flood zones. So the states will have to take the lead. Will Harvey lead even an anti-regulation paradise such as Texas to act?

Inevitably, people want to know if the Harvey flood was worsened by global warming. Well, there’s natural variability (part of “weather’’) and then there’s climate. Most very strong tropical cyclones lose some steam if they movevery slowly over the sea because the turbulence brings up deeper, colder water. But the water in the Gulf over which Harvey slowly traveled has become very warm down very deep. That sounds very much like the effect of global warming. And the storm’s slow movement seems to be linked to a general slowdown in upper-level winds that’s been associated with a warming Arctic.

Finally, it should be said that Texas’s response to the Harvey disaster has been far better (orderly and calm) than Louisiana’s in Katrina. I think that’s mostly because Louisiana is such a corrupt and inefficient place. The leadership of the wheelchair-bound Lone Star State governor, Greg Abbott, has been impressive.

It will be entertaining to see and hear GOP members of Congress who opposed much of the federal funding for Hurricane Sandy recovery fall over themselves to get the maximum bucks from Washington to clean up after Harvey. They’ll get it, especially given the grim fact that most Houstonians don’t have flood insurance. But will they then back land-development and public-infrastructure changes to reduce damage in the next storm? Probably not because that would further enable “Big Government’’ (of which the Sunbelt gets a disproportionate share of the largesse.) Hypocrisy makes the world go round!

What won’t help is that the Trump administration has proposed cutting Federal Emergency Management Agency programs as well as funding for the National Weather Service (whose forecasts for Harvey were very accurate) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, whose services help coastal residents prepare for hurricane and other storm disasters.

By the way, the most prone places for hurricane-related damage in New England are Narragansett Bay and, even more, Buzzards Bay, the upper part of which is in danger of getting some of the biggest hurricane surges in the country. Watch out Wareham! Very vulnerable to fresh water flooding from these storms is the hilly terrain of inland Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut.

David Vallee, with the National Weather Service office in Taunton, Mass., warned The Cape Cod Times of a storm surge in Buzzards Bay where communities such as Bourne and Wareham could see 15 to 25 feet of tidal surge. “Buzzards Bay is the Miami of the Northeast,” Mr. Vallee told the paper.

When will there be a national taxpayer revolt against public money being used to rebuild and rebuild and rebuild structures on the same flood-prone land?

My Cape Cod -- from rural to suburban

The Bourne Bridge, over the Cape Cod Canal, with the Cape Cod Canal Railroad Bridge in the distance.

From Robert Whitcombs's "Digital Diary','' in GoLocal24com

We went down to the Cape the other day to stay with a cousin in a house on a harbor on Buzzards Bay. I thought of how much the Cape had changed since my boyhood, in the ‘50s. Then, much of it was truly rural, with small farms and many cranberry bogs. There were no superhighways. Approaching from Boston’s southeastern suburbs, you’d go down Route 3A, which would become increasingly rustic as you headed south, with farm stands and general stores. The closer we got to the Cape Cod Canal, the more the air smelled like pine, as we entered a state forest.

Then the excitement of crossing the Sagamore Bridge onto an island/peninsula then devoid of big box stores, malls and gated retirement communities and on to my paternal grandparents’ gray-shingled house in the village of West Falmouth, the land of which some of my Quaker ancestors had bought from the Indians in the 1600’s. Then, if there were still time, to the beach, where the water was much cleaner and warmer than in Massachusetts Bay, and where the private bathhouse would get destroyed from time to time in hurricanes, to whichBuzzards Bay is particularly vulnerable.

After that, getting some ice cream from the village’s one and only general store. Then maybe a trip to Woods Hole the next day to see the aquarium of the world-famous Oceanographic Institution there. Woods Hole was where some of my ancestors built boats and partnered in the Pacific Guano Co., where bird excrement from Pacific Islands was processed with fish meal to make what was considered in the 19th Century the best fertilizer. Nowadays, it’s hard to think of Woods Hole as a factory town. Rather, it’s now in effect a college town.

As for West Falmouth, while it’s still almost as pretty as it was 60 years, it’s a ghost town to me since virtually everyone I knew there has died or otherwise gone elsewhere.

Or we occasionally approached the Cape from the west, on Route 6, with its strips of clam shacks, cheap motels and kitschy tourist-oriented gift stores. Ugly, but delightful to young children. Now, of course, you miss the local and often tacky texture on the boring big divided highways. And these highways draw in so much out-of-region traffic that the traffic jams on the two road bridges (there’s also the beautiful railroad bridge) mean driving to the Cape can take considerably longer now than in the ‘50s.

Because of that and because too much of this glacial moraine now looks like exurbia or suburbia, we don’t makemany visits anymore to Olde Cape Cod. Still, the air down there still has a certain luminosity.

Save this jewel of a landscape

Excerpted and revised from an item in Robert Whitcomb's Aug. 11 Digital Diary column in GoLocal24.

Many readers may know the exquisite landscape around Allens Pond, in South Dartmouth, Mass. The mix of very fertile farmland, marsh, river, pond, beautiful beaches on Buzzards Bay and lovely modest old houses is one of the treasures of our region, There are vineyards nearby that recall the Bordeaux region of France. But, as in any such areas close to cities, there are always intense development pressures. In this case, challenges include a proposal for a 38-lot subdivision.

A coalition of groups, led by the Buzzards Bay Coalition (savebuzzardsbay.org) and the Dartmouth Natural Resources Trust (dnrt.org), are trying to raise money and jump through a complicated series of legal and financial hoops to preserve one of the few stretches ofrural coastal landscape in the Northeast megalopolis. Good luck to them!

-- Robert Whitcomb

Oil-spill settlement helps fund shellfish-restoration projects around Buzzards Bay

By ecoRI News staff

BOURNE, Mass. — Buzzards Bay recreational fishermen may soon have access to improved scallop, oyster and quahog populations in town waters for recreational harvests, thanks to settlement funding being used by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and The Nature Conservancy to restore natural resources injured by a 2003 oil spill near the bay’s entrance.

In April 2003, the Bouchard Transportation Co. Barge #120 spilled about 98,000 gallons of fuel oil into Buzzards Bay. The oil spread along more than 90 miles of shoreline and affected wildlife, shellfish beds, recreational activities and habitat. Eight years later, natural resource agencies secured a $6 million settlement to restore wildlife, shoreline and aquatic resources and lost recreational uses.

With the settlement money, the Buzzards Bay/Bouchard B-120 Trustee Council — the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and state agencies from Massachusetts and Rhode Island — has funded 26 projects. Nature Conservancy bay scallop and oyster restoration projects and Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries quahog and oyster restoration work are among the recently funded projects. These restoration efforts are targeting recreational shellfisheries within the impacted Buzzards Bay communities.

“Recreational shellfisheries were tragically affected by the Bouchard spill, with some municipal harvesting areas closed for six months or longer during the peak harvest season due to the oiling,” said John Bullard, regional administrator for NOAA Fisheries Greater Atlantic Region.

The two settlement-funded conservancy shellfish projects are underway. In early June, the conservancy, in collaboration with Bourne municipal shellfish officials, deployed 7,500 caged adult bay scallops in town waters. The goal is to create a spawner sanctuary as an effective way of restoring sustainable bay scallop populations and supporting seasonal recreational shellfishing.

“Bay scallops are a historically and culturally significant species,” said Steve Kirk, the conservancy’s Massachusetts coastal restoration ecologist. “While populations have always fluctuated, we want to bring them back by creating spawner areas to ultimately boost the wild population.”

In collaboration with the town of Fairhaven, the conservancy is using additional settlement money to restore a one-acre oyster bed in Nasketucket Bay.

The Buzzards Bay Coalition is supporting the scallop and oyster restoration work by securing project volunteers and hosting outdoor educational opportunities focused on this shellfish restoration work.

Also funded by the settlement are projects led by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, including multiyear hard clam (quahog) relay and oyster restoration projects. This work involves moving adult quahog stock from an area closed to shellfishing in the Taunton River to designated transplant sites in the waters of Bourne, Dartmouth, Gosnold, Marion, Mattapoisett, New Bedford, Wareham and Westport.

Upwellers for nursery grow-out will be installed and juvenile quahogs will be outplanted in Dartmouth, Wareham and Fairhaven. Outplanting of single field-plant-sized oysters will also take place in Bourne, Marion and Wareham.

The goals of the Division of Marine Fisheries-led projects are to increase overall municipal quahog populations and enhance recreational shellfisheries.

“Boosting the local quahog stocks for local recreational fishermen will be a tangible benefit to those impacted by the spill,” said Division of Marine Fisheries director David Pierce. “Once the transplanted clams are certified clean and held for at least one spawning season after a minimum of six months from relocation, fishermen will have access to this crop. We hope there will be increased quahog reproduction from these transplants, resulting in increased and sustainable harvests from their progeny in the future.''

Atlantic City on Buzzards Bay

Artist's rendition of the proposed New Bedford casino.

By JOYCE ROWLEY, for ecoRI News, where this piece originated.

NEW BEDFORD

On June 23, local voters will get to decide whether the city should have a waterfront casino. The City Council set that date for a binding referendum last week. A ballot question is required under the state’s Massachusetts Expanded Gaming Act for a Category I gaming license.

If the referendum passes, New York City-based development firm KG Urban Enterprises will move forward on licensing a $650 million casino resort complex on MacArthur Drive, and remediate an 11-acre former NSTAR brownfield as part of the project.

“This will bring jobs to the city, it will clean up a contaminated site and it will put us on the map,” City Council President Brian Gomes said. “We are the ideal location.”

New Bedford is one of three communities vying to host the Category I casino allocated to southeastern Massachusetts (Region C). The city of Brockton and the town of Somerset also are going to binding referendum in the next two months on proposals for casinos.

Two other proposed casino operators, one in Springfield and one in Everett, were approved by voters and received gaming licenses in the past two years. Both casinos are expected to be completed in the next five years. In addition, two tribes are also seeking to site casinos in the state.

Last week’s council vote was unanimous, with the abstention of council member Naomi Carney, who left the room during the discussion. Carney has tribal association with the Mashpee Wampanoags, who first had a compact with the town of Middleborough, and are now looking at the city of Taunton for their casino.

Councilman David Alves, chairman of the board’s gaming subcommittee, said with an anticipated 3,000 permanent jobs and more than 2,000 construction jobs, the casino would be the largest economic driver in southeastern Massachusetts.

“We’re in a premier position as a gateway community with the highest unemployment rate, and more than $50 million to be used in an environmental cleanup,” Alves said, ticking off reasons why the state Gaming Commission would choose siting a casino in New Bedford.

He said KG Urban has already invested $13 million over the past five years in preparing for the casino application.

Dana Rebeiro, council member for Ward 4 where the casino would be located, said she was interested in hearing what local residents had to say. “I’m just excited that people have a chance to voice their opinion. This is going to change New Bedford forever.”

Cannon Street Station The host community agreement signed by Mayor Jon Mitchell and Barry Gosin, managing member of KG New Bedford LLC, in March calls for a 300-room hotel, restaurants, retail space, a conference center, a 5-story parking deck and a recreational marina at the site.

Named the Cannon Street Station, the casino would retain the smokestack and iconic New Bedford Gas & Edison Light Complex building on the property. KG New Bedford has committed to investing $10 million in a public harbor walk and pedestrian walkover to connect the casino with the historic district downtown.

Downtown’s Zeiterion Performing Arts Center is identified as the impacted live entertainment venue under the gaming act’s eligibility requirements, and KG New Bedford will provide cross-marketing to it and to existing stores and restaurants in the area.

KG New Bedford has signed an agreement with the local labor union specifying that 20 percent of the construction workforce will be union. And an affirmative action program, also part of the gaming act’s requirements, also is included in the agreement between the city and KG New Bedford.

In exchange for a $12 million payment-in-lieu-of-taxes, the city agrees not to request additional fees or costs for improvements to schools, police or fire services and infrastructure. A $4.5 million preliminary economic regeneration payment to the city was agreed on as required by state law.

Brownfield cleanup The former NSTAR site was used historically by the New Bedford Gas & Edison Light in the late 1880s. The plant manufactured gas until the 1960s. A portion of the property also processed tar, from the 1930s to 1960s, with dockage to offload coal tar from barges for processing.

When seepage of contaminants into New Bedford Harbor was identified in 1996, NSTAR began a site investigationand remediation plan under Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection review. By 2012, steel sheet piling, dredging and capping had contained the contaminants found in the slip areas and bottom sediments, according to state officials.

But the remediation plan only contained the existing onsite material from escaping into the harbor. The site was found to have significant levels of tar, coal tar, fuel oil, cyanide, lead paint, asbestos and mold. KG New Bedford has committed to a $50 million cleanup of those remaining contaminants.

Once KG New Bedford completes the equity verification process, which is expected to be completed by May 4, as part of the Gaming Commission’s licensure requirement, it will move forward with setting up public forums on the referendum.

In addition to other costs, KG New Bedford has agreed to foot the estimated $90,000 special election for the ballot question. According to the Election Commission, the election requires some 200 workers at 36 polling sites.

“As hard as we worked, now it’s left up to our constituency,” Ward 2 Councilman Steve Martins said. “Whichever way they vote, they must come out and vote.”