Tim Faulkner: Offshore wind boom continues, with snags

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

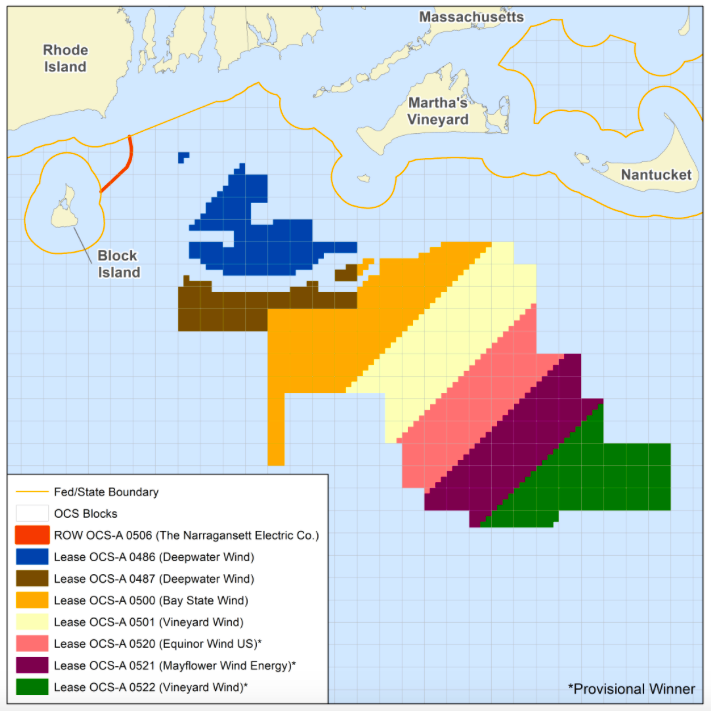

The demand for offshore wind continues, as the designated wind zones in waters south of Rhode Island, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket fill with projects.

At the June 11 meeting of the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC), Grover Fugate, executive director, recounted the growing pains to accommodate as much as 22,000 megawatts of offshore wind.

“This industry has literally exploded overnight,” said Fugate, as he highlighted issues confronting several projects.

The 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind facility, for instance, is deadlocked with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) over the project’s environmental impact statement.

“That’s not something that’s been done before in the NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) world,” Fugate said. “So we’re not quite sure where that is going to end up.”

The Nantucket Historical Commission is seeking $16 million from the Vineyard Wind developer, according to Fugate. The island town has sought funds to compensate for adverse visual impacts the 84 turbines may have on tourism.

Connecticut recently announced it wants to add 2,000 megawatts of offshore wind to the power grid but the state lacks approved offshore wind areas.

“Connecticut, of course, does not have any offshore sources,” Fugate said. “The closest ones to Connecticut are us (Rhode Island).”

Connecticut is already signed on for 300 megawatts from the Revolution Wind project located in one of four wind-lease areas that require CRMC approval.

Rhode Island has already signed up 400 megawatts from the same wind project managed jointly by Ørsted US Offshore Wind and the Massachusetts utility Eversource.

Massachusetts has a goal of 3,200 megawatts of offshore wind by 2035. It has already agreed to buy 800 megawatts from the Vineyard Wind project and the state has issued a request for proposal for an addition 800 megawatts that may come from the second half of the Vineyard Wind lease area.

Vineyard Wind went through a lengthy and contentious review for its initial wind facility and wants to meet with CRMC about a review of the second half of its wind-zone lease.

Bay State Wind, another Eversource and Ørsted project, is also moving forward with an 800-megawatt wind project in the same region. Fugate met with Bay State Wind’s CEO and discussed how the project fails to conform with a 1-mile spacing of turbines within its grid configuration.

Fugate said Bay State Wind is using a European design that doesn’t meet the fisheries requirement for U.S. projects.

“So they are taking that back under consideration,” Fugate said.

Vineyard Wind has filed a proposal to deliver 1.2 gigawatts of wind power to New York along a 95-mile transmission line from Vineyard Wind’s second wind zone, in the easternmost section of the federal wind-lease area. In all, New York is looking for some 9,000 megawatts of wind energy.

“If you add it all up it’s about 22,000 megawatts from New York to the Cape that's under consideration,” Fugate said.

He expressed frustration with the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for not requiring an extended analysis of proposed offshore wind project sites.

“If you don't get two years of baseline data you have no way of measuring the impact,” Fugate said. “That may be intentional on their part, I don't know. But we have pushed for baseline data so that you can measure before and after, so that you know what you just did and how to adjust to it. But without that baseline, we don't know what we just did.”

Cable congestion

The surge in offshore wind development has created a need for transmissions lines and onshore connections to the electric grid. Wakefield, Mass.-based Anbaric Development Partners is creating a renewable-energy center on a leased site at the former Brayton Point coal-fired power plant in Somerset, Mass. Anbaric wants to install two high-voltage electric cables from Brayton Point to serve wind facilities off the coast of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Ørsted would also like to run two cables from its Bay State Wind project to the mainland at Brayton Point.

The transmission lines would run through the the Sakonnet River along the easternmost channel of Narragansett Bay.

Fugate noted that the passage can only accommodate two power cables because of the narrow Stone Bridge corridor between Portsmouth and Tiverton. He said the activity at Brayton Point and other wind-facility operations within Narragansett Bay will be busiest during the summer, causing congestion along the East Passage, which runs between Newport and Jamestown.

“There’s a huge interference with a lot of existing uses down there,” Fugate said.

Federal review

NOAA officials will perform a three-day review of CRMC’s overall coastal program, including a public hearing scheduled for June 18. The review, required every seven years, will culminate with a report of findings that will offer suggested and required actions needed to adhere to federal grant requirements.

In a worst-case scenario, CRMC could face sanctions, which include a loss of federal funding for CRMC’s coastal programs. More than half of CRMC’s budget comes from federal sources.

NOAA’s last evaluation of CRMC was conducted in 2010.

The public hearing will be held at the Department of Administration building, conference room A, One Capital Hill, at 6 p.m.

Matunuck seawall

Hearings are expected in the fall for phase two of a seawall project on Matunuck Beach Road, in South Kingstown, R.I. The first phase was a highly controversial and meaningful case for the CRMC, as it confronts sea-level rise and shoreline erosion from climate change.

Tim Faulkner is an ecoRI News journalist.

Tim Faulkner: Sport and commercial fishermen at odds over offshore wind

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

NARRAGANSETT, R.I. — Commercial fishermen and sport fishermen are split over the benefits of offshore wind facilities.

Commercial fishermen, primarily from eastern Long Island, N.Y., say the wind-energy projects planned for southern New England, such as the South Fork Wind Farm, are the latest threats to their income after decades of quotas and regulations.

“I don't like the idea of the ocean being taken away from me after I’ve thrown so many big-dollar fish back in the water for the last 30 years, praying I’d get it back in the end,” said Dave Aripotch, owner of a 75-foot trawl-fishing boat based in Montauk, N.Y.

In the summer, Aripotch patrols for squid and weakfish in the area where the 15 South Fork wind turbines and others wind projects are planned. He expects the wind facilities and undersea cables will shrink fishing grounds along the Eastern Seaboard.

“If you put 2,000 wind turbines from the Nantucket Shoals to New York City, I’m losing 50 to 60 percent of my fishing grounds,” Aripotch said during a Nov. 8 public hearing at the Narragansett Community Center.

Dave Monti of the Rhode Island Saltwater Anglers Association said the submerged turbine foundations at the Block Island Wind Farm created artificial reefs, boosting fish populations and attracting charter boats like his.

“It’s a very positive thing for recreational fishing,” Monti said. “The Block Island Wind Farm has acted like a fish magnet.”

Offshore wind development also has the support of environmental groups such as the National Wildlife Federation and the Conservation Law Foundation, which view renewable energy as an answer to climate change.

“Offshore wind power really is the kind of game-changing large-scale solution that we need to see move forward, particularly along along the East Coast,” said Amber Hewett, manager of the Atlantic offshore wind energy campaign for the National Wildlife Federation.

Aripotch and fellow commercial fisherman Donald Fox urged the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to study the cumulative effects of the four other wind projects planned for the Rhode Island/Massachusetts wind-energy area. They want to know how catches and quotas will be calculated if fishing nets run through multiple wind facilities.

“God bless you if you figure that one out,” Fox said.

Commercial fisherman David Aripotch said offshore wind turbines and the accompanying infrastructure will shrink fishing grounds along the Eastern Seaboard. (Tim Faulkner/ecoRI News photos)

The comments were made at the last of three public hearing held by BOEM for the South Fork Wind Farm’s environmental impact statement (EIS). A 30-day public comment period on the environmental impacts ends Nov. 19. BOEM has held a total of eight public meetings for the South Fork project.

After the current comment period, a second 45-day comment period will follow BOEM’s release of a draft IES. BOEM then has three months to issue a decision, which is expected in early 2020. If approved, construction on the South Fork Wind Farm would begin in 2021. Pending other permits, the wind facility would then be expected to be operating by the end of 2022.

BOEM is reviewing the engineering plans for the wind turbines, an offshore substation, and the 30-mile power cable that will run to East Hampton, N.Y. The federal agency also is reviewing the effects of the transmission line, such as the impacts of electromagnetic fields on sea life.

The substation would be above the water on its own platform or share a platform with a wind turbine. It will have a height of up to 200 feet to support a high-voltage power transformer, reactor, and ventilation and air-conditioning systems. The substation may also include a 400-horse-power diesel generator and a 500-gallon diesel fuel tank.

Sportfisherman Dave Monti said the submerged turbine foundations at the Block Island Wind Farm created artificial reefs, boosting fish populations and attracting charter boats like his.

The designated wind area between Block Island and Martha’s Vineyard has already restricted wind-energy development in portions of prime fishing grounds such as Cox Ledge.

Bonnie Brady of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association called Deepwater Wind “the not ready for primetime players” because of technical problems with the Block Island Wind Farm, such as exposed undersea cables.

Brady noted that Deepwater Wind, now called Ørsted U.S. Offshore Wind, increased the capacity of the proposed South Fork Wind Farm from 90 to 130 megawatts. Each turbine can have an electricity output of 12 megawatts, or twice the power output of the Block Island turbines. The maximum height of the new turbines is 840 feet. The Block Island turbines are about 580 feet tall.

Brady wants BOEM to study of the effects of the larger turbines and increase the space between each turbine to 2 miles. Deepwater Wind has offered to separate the turbines by a mile. She said studies are needed of the noise and particle pressure from the larger turbines and the impacts of jet plowing and pile driving on fish and shellfish.

Brady is advocating for BOEM and New York regulators to afford fishermen the same protections that Rhode Island fishermen receive, such payment for lost revenue, as defined by the Ocean Special Area Management Plan.

“There needs to be long-term mitigation, long-term compensation at fair values, without signing a nondisclosure agreement,” she said.

Tim Faulkner, nature writer, is a reporter and writer for ecoRI News

Spinning blades of offshore wind turbines found to create little noise

Block Island Wind Farm.

From eco RI News (ecori.org)

New research lead by the University of Rhode Island has concluded that offshore wind facilities produce minimal noise above and in the water while the blades are spinning. But the noise and vibrations from building them are a concern.

The research, funded through the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, began with the construction of Deepwater Wind’s Block Island Wind Farm in September 2015. It continued when the five turbines began spinning in late 2016.

Through acoustic monitoring, James Miller, URI professor of ocean engineering and an expert on ocean sound propagation, found that the sound from the turbines was barely detectable underwater.

“You have to be very close to hear it. As far as we can see, it’s having no effect on the environment, and much less than shipping noise,” Miller said.

Working with a team of specialists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Marine Acoustics Inc. of Newport, and others, Miller heard ships, whales, wind, and fish. But noise measurements 50 meters from the turbines was hardly audible. Above the waterline, the swish of blades was barely heard, according to Miller.

The noise was monitored using hydrophones in the water and geophones, which measure the vibration of the seabed, on the seafloor.

The vibrations from the pile driving of the turbine’s support structure is a bigger unknown. Miller said the vibrations on the seabed had a surprising intensity that may harm bottom-dwelling organisms such as flounder and lobsters, which have a huge economic value in the state.

“Fish probably can’t hear the noise from the turbine operations, but there’s no doubt that they could hear the pile driving,” Miller said. “And the levels are high enough that we’re concerned.”

To minimize the aquatic impacts, the pile driving started with minimal sound to allow marine life to move away. Pile driving was also prohibited between Nov. 1 and May 1 to protect migrating North Atlantic right whales, which are critically endangered. The pile driving was also limited to daytime so that spotters could search for nearby whales.

This kind of monitoring will continue once construction starts on other Deepwater Wind offshore wind farms such as the Skipjack Wind Farm, off the coast of Ocean City, Md. Additional research will be conducted in the federal offshore wind energy area between Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

In addition to the acoustic impacts, the researchers looked at the impacts of offshore wind facility construction and operations on fishing, habitats and seabed scaring and healing. Studies will eventually be published from that research.

URI expects to study and provide data for the nearly 1,000 offshore wind turbines that have been proposed for installation in the waters between Massachusetts to Georgia in the coming years.

“We’ve become the national experts, which has added to Rhode Island’s reputation as the Ocean State,” Miller said.

Get ready for oil/gas drilling off the Northeast?

By JOYCE ROWLEY/ecoRI News contributor

From EcoRi News

When the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) released its notice of intent to scope an environmental review for Atlantic Ocean oil and gas leases in January, it left little room for public comment at meetings. Using an open house-style meeting, BOEM’s Web site states the meetings “will not include a designated session for formal oral testimony.”

But by the third meeting, held Feb. 17 in Wilmington, N.C., 400 people had signed up to speak and 150 protesters convened at the meeting site, opposed to opening up any part of the Atlantic Ocean to the potential impacts of a BP Deepwater Horizon disaster.

The scoping sessions stem from BOEM’s 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Draft Proposed Program (DPP), released last month. Five-year plans are prepared under the 1953 Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Lands Act.

However, this DPP calls for opening up sectors off the Mid-Atlantic states and off the Southeast to oil and gas drilling for the first time since 1983, triggering a programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS) under the National Environmental Policy Act.

Atlantic Ocean OCS leases expired in the mid-1990s, after exploratory wells came up empty. Forty-three exploratory wells were sunk off the Northeast, one off the Mid-Atlantic states and seven off the Southeast.

BOEM contends those studies are outdated, and against strenuous objections from environmentalists, commercial and recreational fishing industries, state and federal legislators, and tens of thousands of individuals, BOEM approved a PEIS for geotechnical and geophysical (G&G) studies in the Atlantic last summer. BOEM is now working with coastal states and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to secure permits, including incidental “takes” of marine mammals and endangered species of turtles. Eight G&G contractors haveapplications pending for the work.

Back in the mix Two years after congressional restrictions expired in 2008, the Atlantic OCS planning areas were put into the 2012-2017 plan. A PEIS published in early April 2010 included only the Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic planning areas. But just as Northeast coastal communities breathed a sigh of relief, BP’s Deepwater Horizon exploratory oil rig exploded, creating the nation’s worst environmental disaster in its history.

In December 2010, the Atlantic planning areas were excluded from the final program plan. Six months later, governors in several Southern states formed the Outer Continental Shelf Governors Coalition, to expand areas for offshore energy development and regional revenue sharing. Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, the former chairman of the Democratic National Party, also joined the coalition in asking for oil and gas drilling in the Mid-Atlantic.

Environmental groups, such as the North Carolina Chapter of the Sierra Club and the South Carolina Conservation League, had been protesting against use of the Atlantic OCS for three years. But U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Sally Jewell has said that it was Governors Coalition’s lobbying for opening the Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic that convinced her to include these areas in the 2017-2022 DPP.

At the Feb. 20 Governors Association Conference in Washington, D.C., the Outer Continental Shelf Governors Coalition discussed putting legislation through Congress for federal-state sharing of royalties, bonus bids and rents from Atlantic offshore oil and gas development.

In opposition Virginia Congressmen Gerald Connolly, Bobby Scott and Donald Beyer have written Jewell asking her to exclude the Mid-Atlantic from consideration.

“Drilling on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf (AOCS) is a source of considerable debate in the Commonwealth. It threatens local economies, ecosystems, natural resources, and poses significant national security concerns,” the congressmen wrote.

The letter went on to say that the action puts at risk 91,000 tourism, recreation and fisheries jobs that represent $5 billion of Virginia’s GDP for “a few days’ worth of national oil and gas supply.”

This month’s public protests are a small segment of a much larger public outcry. Federal and state leaders, environmental NGOs and some 285,000 individuals have written in opposition. Senators Jack Reed, D-R.I., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Ed Markey, D-Mass., co-signed a letter in opposition with five other senators.

Rep. David Price, D-N.C., wrote a letter co-signed by 36 other members of Congress, which read in part:

“We believe that the circumstances that informed the exclusion of Atlantic planning areas under the existing Five-Year Program remain unchanged. Additionally, significant federal, state, and local resources have been expended in an effort to improve the health of Atlantic fisheries, protect endangered and threatened species that rely on the Atlantic Ocean and coast, and ensure the continued economic vitality of coastal areas through recreation and tourism. We believe that allowing oil and gas development in the Atlantic would be inconsistent with and contrary to these ongoing efforts.”

Upon release of the 2017-2022 DPP last month, Markey, with senators Cory Booker, D-N.J., Robert Menendez, D-N.J., and Ben Cardin, D-Md., held a press conference seeking administrative withdrawal of the Atlantic planning areas.

Areas can be excluded one of three ways: by presidential administrative withdrawal, as has happened with the North Aleutian planning area in Alaska; by a congressional moratoria, which protected the East Coast from consideration until 2008 and now protects the Eastern Gulf of Mexico; or by the secretary of the interior.

Markey has noted that the existing 2012-2017 DPP utilizes 75 percent of all U.S. oil and gas reserves currently available, yet less than a quarter of all leases are actively developed. Addition of the Atlantic Ocean planning areas proposed would only increase accessible reserves by 5 percent, according to Markey.

Citing a recent Oceana economic analysis comparing offshore drilling and wind energy, Markey said:

“Offshore oil spills don’t respect state boundaries. A spill off the coast of North Carolina could affect Massachusetts. We saw what happened after the BP spill. My state’s fishing and tourism industry can’t afford that kind of tragedy.”

Noting there has never been a tragic wind-energy spill, Markey went on to say that Congress has yet to enact key drilling safety reforms, such as raising the liability cap for an offshore spill and increasing the civil penalties that can be levied against oil companies that violate the law.

Currently, the liability limit is set at $73 million for damages caused by an offshore oil spill.

The latest cost estimate for the BP spill is $46 billion in clean-up efforts and damages. In 2012, BP pled guilty to 11 felony charges in the deaths of 11 workers killed in the explosion and paid $4 billion. Last September, BP appealed a federal court ruling that 4.2 million barrels were spilled, claiming a much lower 2.5 million barrels flowed from its damaged well. The court may award damages of up to $4,300 per barrel under the federal Clean Water Act.

The most recent incident data available for the Gulf of Mexico indicates there have been 22 loss-of-well-control incidents, 461 fires/explosions, 989 injuries and 11 fatalities between 2011-2014. There were three major spills in 2011 and eight in 2012.

Public comment The last two Atlantic region meetings on the environmental scoping document are scheduled to be held March 9 in Annapolis, Md., and March 11 in Charleston, S.C.

There are two separate documents in progress — the 2017-2022 DPP and the scoping for the PEIS. Comments submitted to one will not be automatically included with the other. Comments will be accepted until March 30.

For the 2017-2022 DPP, submit online or in writing to Ms. Kelly Hammerle, Five-Year Program Manager, BOEM (HM–3120), 381 Elden St., Herndon, VA 20170.

To comment on the scope of the PEIS, submit online or mail in an envelope labeled ‘‘Scoping Comments for the 2017–2022 Proposed Oil and Gas Leasing Program Programmatic EIS’’ to Mr. Geoffrey L. Wikel, Acting Chief, Division of Environmental Assessment, Office of Environmental Program (HM 3107), Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, 381 Elden St., Herndon, VA 20170–4817.

Portions of this article used reporting by the Wilmington (N.C.) Star and The Myrtle Beach (S.C.) Sun News.