Crafts for sale

Installation view of the “Holiday Handmade” shop at the Fuller Craft Museum, in Brockton, Mass., through Jan. 7

The museum says:

The shop showcases goods that “wouldn't look out of place hanging on the walls of the museum itself. This year's shop features textiles, paintings, ceramics and even cosmetics crafted with an eye for artistic flair and good design.’’

Brockton City Hall

— Photo by Timothy Valentine

A heavyweight character

Rocky Marciano (1923-1969) in about 1953. He was heavyweight boxing champion of the world in 1952-1956 and retired undefeated. He grew up in the old shoemaking city of Brockton, Mass.

Main Street in Brockton in the early 20th Century.

”I was on a plane with him one time when he was the champion. And of course coming from Massachusetts, Rocky Marciano was my favorite. You play your character and it isn't right to step out of it. You have to stay in that character….Rocky Marciano had such guts and heart. He was something special.’’

— Robert Goulet (1933-2007), Canadian-American singer and actor. He was a native of Lawrence, Mass.

Scanning the ‘undertow’

“Each, Every, All, None’’ (mixed media), by Brockton, Mass.-based artist Virginia Mahoney in her show with Natalie Miebach, “Undercurrents,’’ at Fountain Street Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 29.

The gallery says:

“Virginia Mahoney scans the undertow of human interactions, examining the disparity between surface appearances and underlying consequences. With complex, intricate forms and materials, her figures probe autobiographical stories and question accepted narratives. As she uncovers possibilities in the scraps, shards, and leftovers of a longstanding studio practice, her voice emerges in the rhythm of stiches, provocations of language, and discovery of new forms.’’

Headlines posted in street-corner window of newspaper office (Brockton Enterprise), 60 Main Street, Brockton, in December 1940. Upstairs were the first main offices of the W.B. Mason company.

We still make 'em

New Balance running shoes

Early 19th Century shoemaking shop displayed at the Maine State Museum, in Augusta

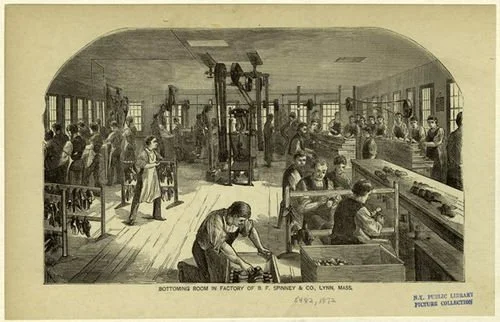

By the mid to to late 19th Century, the shoemaking industry had migrated to the factory and was increasingly mechanized. Here’s the bottoming room of the B. F. Spinney & Co. factory, in Lynn, Mass., in 1872

The shoe industry was once huge in New England. It was concentrated in eastern Massachusetts, particularly in Lynn and Brockton, but Maine and New Hampshire had shoemaking centers, too. And some of the companies that served the industry were big, too— most notably United Shoe Machinery Corp., based for decades in its Art-Deco skyscraper on Federal Street in downtown Boston. But by the mid-20th Century, much of the industry had moved south, in search of cheaper labor. But a few shoe companies remain in the region.

The following is edited from a New England Council report:

“New Balance, the Boston-based footwear maker, opened manufacturing facilities in Skowhegan, Maine, and Londonderry, N.H., as part of its efforts to expand U.S. manufacturing capacity. The company aims to enhance its American supply network through innovation, automation] and robotics.

“With the $65 million Skowhegan expansion, New Balance will add a 120,000-square-foot single-story addition to the existing facility, doubling production capabilities and creating 200 new jobs. Additionally, the Londonderry facility would cover 102,418 square feet and includes office and manufacturing space, seven loading docks, and LED lighting. New Balance expects to hire 250 employees initially and up to 450 upon completion of the project.

“‘ New Balance has always been strongly committed to the communities where our associates live and work,’ said Raye Wentworth, director of domestic manufacturing at the company. ‘We’re thrilled to be able to support this important opportunity to add quality, affordable education and child-care resources for local families.”

An ad for the long-gone, high-end Brockton, Mass.-based shoemaker the Geo E. Keith Co., whose famous trade name was Walk-Over

#New Balance

#shoemaking

‘Riotous threads’

“Wizard of Oz”, in by Janet Inman, in the show “Riotous Threads: Fiber Works from Gateway Arts,’’ at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, Mass.

“Riotous Acts’’ encompasses work by artists with disabilities who work within the educational structure of Gateway Arts, in Brookline, Mass. The museum says that the show’s fiber art includes weaving, embroidery, thread collections and cloth doll making. “Embroidery dominates and colorful, thick thread and large needles help to make the designs bold and easy to understand.’’

Talking therapy in Brockton

“Conversation” (clay, graphite,), by Melissa Stern, in her show “Melissa Stern: The Talking Cure,’’ at the Fuller Art Museum, Brockton, Mass., Jan. 29-May 15.

The museum says that these witty (and sometimes unsettling) sculptures "are a spirited cast of characters formed in clay." The show takes its name from Sigmund Freud’s description of psychoanalysis, and centers on Ms. Stern’s 12 ceramic sculptures. The artist invited 12 writers to create inner monologues for each of the characters and 12 actors to perform them for audio recordings.

Brockton City Hall, which opened in 1892 during Brockton’s heyday as a center of manufacturing, especially of shoes.

Fear and wonder at the Fuller

“Nesting’’ (concrete, wood, bronze, steel and ashes), by Elizabeth Helfer, in the group show “Beyond the Walls: Sculptures from the New England Sculptors Association,’’ at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, Mass., through Sept. 12.

This exhibit uses the museum's 22-acre outdoor space, with sculptures throughout the property.

The museum says:

"Nesting’’ uses “a muted color palette and a combination of natural and manmade materials to convey an admiration for nature that is equal parts fear and wonder.

Second-hand savagery

“Bird Skin” (wall-mounted discarded clothing and upholstery fabric), by Tamara Kostianovsky, in her show “Savage Legacy,’’ at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, Mass., through Aug. 22

The gallery says: “The exhibition includes Kostianovsky’s signature textile ‘meat’ sculptures made with the artist’s own clothing, sculptures of birds composed of discarded upholstery fabrics, and recent forms that reference tree stumps and severed tree limbs.’’

Get it over with

Rocky Marciano (second from left) with Boston Mayor John F. Collins (center-right) and comedian and singer Jimmy Durante (right and famous for his impressive nose), circa 1968. The man at left is unidentified.

“Why waltz with a guy for 10 rounds if you can knock him out in one?’’

— Rocky Marciano (birth name) (1923-1969), an American professional boxer who competed from 1947 to 1955, and held the world heavyweight title from 1952 to 1956. He is the only heavyweight champion to have finished his career undefeated. He was born and brought up in the shoe-making city of Brockton, Mass. Her died in a plane crash in 1969.

A shoe factory back when Brockton called itself “The Shoe Capital of the World.’’ My paternal grandfather was a manager in the George E. Keith Co., which made Walk Over shoes, which were considered high end. Brockton went into steep decline with the departure of most of New England’s shoe industry for the South and abroad. But the city has enjoyed a bit of a revival in recent years, as some entrepreneurial energy from very rich Greater Boston has spilled into the old mill town.

— Robert Whitcomb

Martha Bebinger: Mass. COVID-19 contact tracers might offer milk or help with rent

BOSTON

It’s a familiar moment. The kids want their cereal and the coffee’s brewing, but you’re out of milk. No problem, you think — the corner store is just a couple of minutes away. But if you have COVID-19 or have been exposed to the coronavirus, you’re supposed to stay put.

Even that quick errand could make you the reason someone else gets infected. But making the choice to keep others safe can be hard to do without support.

For many — single parents or low-wage workers, for instance — staying in isolation is difficult as they struggle with how to feed the kids or pay the rent. Recognizing this problem, Massachusetts includes a specific role in its COVID-19 contact-tracing program that’s not common everywhere: a care resource coordinator.

Luisa Schaeffer spends her days coordinating resources for a densely packed, largely immigrant community in Brockton, Mass.

On her first call of the day recently, a woman was poised at her apartment door, debating whether to take that quick walk to get groceries. The woman had COVID-19. Schaeffer’s job is to help clients make the best choice for the public — sometimes, the help she offers is as basic, and important, as the delivery of a jug of milk.

“That’s my priority. I have to put milk in her refrigerator immediately,” Schaeffer said.

“Most of the time it’s the simple things, the simple things can spread the virus.”

The woman who needed milk was one of eight cases referred to Schaeffer through the state government’s Community Tracing Collaborative. Contact tracers make daily calls to people in isolation because they’ve tested positive or those in quarantine because they’ve been exposed to the coronavirus and must wait 14 days to see if they develop an infection. The collaborative estimates that between 10% and 15% of cases request assistance. Those requests are referred to Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators.

“So many people are on this razor-thin edge, and it’s often a single diagnosis like COVID that can tip them over,” said John Welch, director of operations and partnerships for Partners in Health’s Massachusetts Coronavirus Response, which manages the state’s contact-tracing program.

He said a role such as resource coordinator becomes essential in getting people back to “a sense of health, a sense of wellness, a sense of security.”

With milk on its way, Schaeffer dialed a woman who needed to find a primary-care doctor, make an appointment and apply for Medicaid. That call was in Spanish.

With her third client, Schaeffer switched to her native language, Cape Verdean Creole. The man on the other end of the line and his mother had both been sick and out of work. He applied for food stamps and was denied. Schaeffer texted the regional head of a state office that manages that program. A few minutes later, the director texted back that he was on the case.

Schaeffer, who has deep roots in the community, is on temporary loan to the state’s contact-tracing collaborative and will later return to her job, helping patients understand and follow their prescribed treatments at the Brockton Neighborhood Health Center.

The collaborative said most client requests are for food, medicine, masks and cleaning supplies. COVID-19 patients who are out of work for weeks or who don’t have salaried jobs may need help applying for unemployment or help with rental assistance — available to qualified Massachusetts residents.

Care-resource coordinators even connect people with legal support when they need it. An older woman employed in the laundry room at a nursing home was told she wouldn’t be paid while out sick. Schaeffer got in touch with the Community Tracing Collaborative’s attorney, who reminded the company that paid sick leave is required of most employers during the pandemic.

“So, now, everything’s in place. She started getting paid,” Schaeffer said.

There are glitches as the care-resource coordinators try to support people isolating at home. Some workers who are undocumented return to work because they fear losing their jobs. When the local food bank runs out, Schaeffer has had to scramble to find a local grocer to help. The free canned goods or vegetables can be like foreign cuisine for Schaeffer’s clients, some of whom are from Cape Verde and Peru. In those cases, she can reach out to a nutritionist and set up a cooking lesson via conference call.

“I love the three-way calls,” she said, beaming.

Schaeffer and other care resource coordinators have responded to more than 10,500 requests for help so far through Massachusetts’s contact-tracing program. Demand is likely greater in cities such as Brockton, with higher infection rates than most of the state and a 28.7 percent lower median household income.

Massachusetts has carved out care-resource coordination as a separate job in this project. But the role is not new. Local health departments routinely include what might be called support or wrap-around services when tracing contacts. With cases of tuberculosis, for example, a public-health worker might make sure patients have a doctor, get to frequent appointments and have their medications.

“You can’t have one without the other,” said Sigalle Reiss, president of the Massachusetts Health Officers Association.

Partners in Health’s Welch, who is advising other states on contact tracing, said the importance of having someone assist with food and rent while residents isolate isn’t getting enough attention.

“I don’t see that as a universal approach with other contact-tracing programs across the U.S.,” he said.

Some contact-tracing programs that schools, employers or states have erected during the pandemic cover only the basics.

“They’re focused on: Get your positive case, find the contacts, read the script, period, the end,” said Adriane Casalotti, chief of government and public affairs at the National Association of City and County Health Officials. “And that’s really not how people’s lives work.”

Casalotti acknowledged that the support role — and services for people isolating or in quarantine — adds to the cost of contact tracing. She urges more federal funding to help with this expense as well as a federal extension of the paid sick time requirement, and more money for food banks so that people exposed to the coronavirus can make sure they don’t give it to anyone else.

“Individuals’ lives can be messy and complicated, so helping them to be able to drop everything and keep us all safe — we can help them through the challenges they might have,” Casalotti said.

This story is part of a partnership that include WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Martha Bebinger, WBUR: marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger

Brockton City Hall, built in 1892, back in the era when the city called itself “The Shoemaking Capital of the World.’’

Things that evoke COVID themes at Fuller Craft Museum

“Double Rocker, Back to Back” (cherry, maple and milk paint), by Tom Loeser, in the Fuller Craft Museum’s (Brockton, Mass.) group show “Shelter, Place, Social, Distance: Contemporary Dialogues From the Permanent Collection’’ through Nov. 22.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum has pulled from its permanent collection items that speak to themes of home, community, isolation and other ideas /topics that the current crisis evokes.

Beauty in Brockton

“Blackbird” (glass), by Natasha Harrison, at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, Mass. Brockton is gritty in many places, as you might expect in an old shoe-making center, but the Fuller is in a beautiful park with a lovely pond.

Have a ball in Brockton

Wheel vase, blue, purple, and opalescent white glaze, by Thomas Bezanson, a Benedectine monk, in his show "Brother Thomas: Seeking the Sublime,'' at the Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, Mass. The show includes a range of his pottery, from tea bowls to vases.

Brockton in the late 19th Century and the first part of the 20th was one of the shoe-making capitals of the world. Eventually, however, most of its shoe companies closed or went south of abroad in search of cheap labor. The city has never fully recovered from this exit, although its proximity to the wealth of Boston has softened the blow. Several local cultural institutions, such as the Fuller, were founded by shoe moguls. The museum is in a surprisingly lovely park setting, whatever Brockton's gritty reputation.

One of the Brockton area's many shoe factories in 1910.

Frank Carini: Brockton's water use threatening region's environment

By FRANK CARINI

In late October of last year, the water level of Silver Lake, in the Brockton, Mass., area, was down 72 inches, or 6 feet. Three weeks later, in mid-November, the level had dropped another 8 inches. Large portions of Massachusetts remain under drought conditions, but Alex Mansfield and Pine duBois of the Jones River Watershed Association claim the lake’s demise is a preventable manmade crisis.

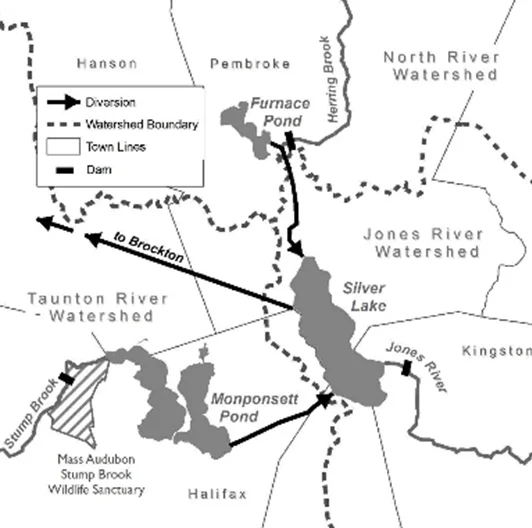

They and others blame the problem on decades of overuse and misuse of local and regional waters. The city of Brockton, for instance, takes about 10 million gallons daily out of Silver Lake and pumps it 20 miles through two pipes, one of which is more than 100 years old.

The water level of 640-acre Silver Lake, which touches three Massachusetts communities, Pembroke, Kingston and Plympton, is at a 30-year low, according to Mansfield. He said this fact shouldn’t surprise anyone. In fact, both he and duBois say it’s long been known that Silver Lake can’t sustain that amount of daily withdrawal. It can’t even sustain half the current daily allotment, according to duBois.

Mansfield said the city of Brockton tracks the lake’s water level and water quality daily. ecoRI News spoke with Mansfield and duBois on the evening of Jan. 4. They said Silver Lake’s water level was down another foot and a half from mid-November.

“This issue doesn’t have anything to do with drought,” Mansfield said. “It’s about the city taking too much water. And the thing is we haven’t seen anything close to the worst of it. We’re starting 2017 at a 30-year low, and it’s so low that the lake isn’t going to rebound by April. That’s a bad starting point.”

Silver Lake, which lies within the Jones River watershed, is the 12th-largest natural lake in Massachusetts. When substantially drained, many additional feet of lakebed are exposed, and slow-moving animals, most notably freshwater mussels that clean the lake water of nutrients, can’t keep up with the receding shore and die.

Mansfield said the current crisis has killed fish, turtles and “tens of thousands” mussels. He also noted that people are riding their ATVs around the dry lakebed.

The city of Brockton gets its water from Silver Lake and several ponds in the surrounding area. (Mass Audubon)

The pumping of Silver Lake and other area waterbodies to meet Brockton’s water needs is impacting water quality and wildlife habitat from Halifax to Cape Cod, according to the Jones River Watershed Association (JRWA). Both Tubbs Meadow Brook, Silver Lake’s largest inflow, and Mirage Brook, a sub-watershed that makes up 25 percent of Silver Lake’s watershed, are stressed, according to the Kingston-based organization.

“The city of Brockton couldn’t care less,” said Mansfield, noting that the city is still negotiating a consent order with the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). “They continue to say there’s no problem.”

In a Jan. 5 e-mail to ecoRI News, Larry Rowley, Brockton’s Department of Public Works commissioner, wrote that the city is “still in negotiations with DEP on this issue so no one should be discussing anything about this. When we have a final agreement we would be happy to talk to you.”

The city of Brockton began pumping water from Silver Lake in 1904. Several times during the next five decades the city was encouraged to find additional sources, or likely face water shortages. The advice was ignored.

In 1964, Brockton and the lake’s surrounding communities got a first-hand look at the predicted impact, when Silver Lake was drawn down by more than 8 feet, like it is now. The city had to stop drawing water from the lake for several months. The crisis prompted the creation of a special commission to find Brockton more water.

The commission’s report found that Silver Lake couldn’t supply more than 4.5 million gallons daily. Despite local opposition, however, the report eventually lead to an emergency legislative action that allowed Brockton to divert water from Monponsett Ponds in Halifax and Furnace Pond in Pembroke into Silver Lake, to expand the city’s water supply.

The decision to increase Brockton’s regional water withdrawals — the JRWA says 11 million gallons a day from all sources is the recommended limit — has had an adverse impact on the environment, according to Mass Audubon.

Among those impacts, according to the organization, are: lack of flow to Jones River, from Silver Lake, Stump Brook, from Monponsett Ponds, and Herring Brook, from Furnace Pond, during significant periods of the year; severe drawdown of Silver Lake for months at a time every year; habitat for fish and other aquatic life in local waterways is severely degraded, and in some cases eliminated for months at a time; and both Monponsett Ponds and Furnace Pond both have excessive-nutrient problems.

The special commission also suggested that connecting Brockton to the Metropolitan District Commission — now the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) — water supply would be the better solution, But it was decided that such an effort would take too long to address the existing emergency.

A decade later, in 1974, a consulting firm was hired to examine the city’s existing water supplies and needs. It determined that Brockton still didn’t have enough water to survive a drought. Nothing was done. In both 1982 and ’86, Massachusetts had to enact water-supply emergencies because Brockton had drawn Silver Lake down by as much as 20 feet.

A search began for more water. Connecting to the MWRA water supply was again recommended. The idea was again ignored. Instead, a desalination plant was built on the western banks of the Taunton River in Dighton. The facility takes water from the lower part of the Taunton River and purifies it to drinking-water standards.

Since the Aquaria Desalination Plant went on-line in 2008 it has supplied Brockton with about 3 percent of its annual water needs. Last year, the plant supplied less than 7 percent of the city’s water.

Mansfield said Brockton has never made the switch to MWRA water because of cost. “It’s more expensive than taking water out of the lake,” he said. “The desalination plant is barley used because the city doesn’t want to get locked into using it.”

The MWRA was established by an act of the Legislature in 1984 to provide wholesale water and sewer services. Today, the agency serves some 2.5 million people and more than 5,500 large industrial users in 61 cities and towns.

The 1964 Legislative act didn’t include any protections for Silver Lake, but it did include protections for Monponsett and Furnace ponds. The act set limits on when water can be diverted: no diversions in the summer when there are recreational uses; no diversions when the ponds are low; and no diversions when water quality presents a public-health risk, for example.

These important protections mean these additional water supplies aren't always available. Monponsett Ponds have been suffering from poor water quality for more than year. Excessive nutrient loading, lack of flushing and other problems have led to blooms of potentially toxic cyanobacteria. In fact, cyanobacteria cell counts have been measured in the millions per milliliter, far exceeding the public-health standards for swimming, according to the DEP.

The DEP has found that the nutrient levels of Monponsett Ponds, most notably West Monponsett Pond, are more than 300 times what they should be, which is fueling the cyanobacteria blooms.

Silver Lake also has spent time on the Massachusetts impaired waters list, for “fish, other aquatic life and wildlife,” according to DEP. The Jones River, which flows out of Silver Lake, is impaired in terms of “aesthetics, fish and wildlife, and recreational contact.” The river’s specific impairments include low dissolved oxygen and excess algae growth. DEP cites “flow alterations from water diversions” as the reason for these impairments.

“The quality of the ponds that go into Silver Lake have been degraded,” Mansfield said. “Bacteria blooms, swimming bans, no pets in the water. The entire arrangement has caused water-quality problems.”

Welcome to Brockton

Brockton City Hall, a Romanesque pile built in 1892-94 as the city was moving toward its most prosperous period, albeit with such horrors as child labor and gruesome industrial accidents.

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb's Dec. 1 "Digital Diary'' in GoLocal24.

Brockton, once the shoemaking capital of the world, is another mostly deindustrialized area. But immigrants have moved there in large numbers, drawn by cheap rents and Massachusetts’s relatively generous social services, including healthcare.

MayorWilliam Carpenter was recently under fire for spending $585 in city money to pay for a community college course for himself in Cape Verdean Creole to better communicate with a major ethnic group there. The City Council eventually approved the expenditure after some grumbling that he should have paid for it himself.

Of course, immigrants used to flock to such cities as Brockton for jobs, many of them relatively high-paying skilled positions. No more. Now the large number of low-income immigrants, many with little or no skills in English, serve to irritate many of the sort of people who voted for Donald Trump. They make some Americans feel that they are strangers in their own land.

But just up the road, Boston and Cambridge get richer and richer with 21st Century high tech and an embrace of a global economy.

-- Robert Whitcomb

Atlantic City on Buzzards Bay

Artist's rendition of the proposed New Bedford casino.

By JOYCE ROWLEY, for ecoRI News, where this piece originated.

NEW BEDFORD

On June 23, local voters will get to decide whether the city should have a waterfront casino. The City Council set that date for a binding referendum last week. A ballot question is required under the state’s Massachusetts Expanded Gaming Act for a Category I gaming license.

If the referendum passes, New York City-based development firm KG Urban Enterprises will move forward on licensing a $650 million casino resort complex on MacArthur Drive, and remediate an 11-acre former NSTAR brownfield as part of the project.

“This will bring jobs to the city, it will clean up a contaminated site and it will put us on the map,” City Council President Brian Gomes said. “We are the ideal location.”

New Bedford is one of three communities vying to host the Category I casino allocated to southeastern Massachusetts (Region C). The city of Brockton and the town of Somerset also are going to binding referendum in the next two months on proposals for casinos.

Two other proposed casino operators, one in Springfield and one in Everett, were approved by voters and received gaming licenses in the past two years. Both casinos are expected to be completed in the next five years. In addition, two tribes are also seeking to site casinos in the state.

Last week’s council vote was unanimous, with the abstention of council member Naomi Carney, who left the room during the discussion. Carney has tribal association with the Mashpee Wampanoags, who first had a compact with the town of Middleborough, and are now looking at the city of Taunton for their casino.

Councilman David Alves, chairman of the board’s gaming subcommittee, said with an anticipated 3,000 permanent jobs and more than 2,000 construction jobs, the casino would be the largest economic driver in southeastern Massachusetts.

“We’re in a premier position as a gateway community with the highest unemployment rate, and more than $50 million to be used in an environmental cleanup,” Alves said, ticking off reasons why the state Gaming Commission would choose siting a casino in New Bedford.

He said KG Urban has already invested $13 million over the past five years in preparing for the casino application.

Dana Rebeiro, council member for Ward 4 where the casino would be located, said she was interested in hearing what local residents had to say. “I’m just excited that people have a chance to voice their opinion. This is going to change New Bedford forever.”

Cannon Street Station The host community agreement signed by Mayor Jon Mitchell and Barry Gosin, managing member of KG New Bedford LLC, in March calls for a 300-room hotel, restaurants, retail space, a conference center, a 5-story parking deck and a recreational marina at the site.

Named the Cannon Street Station, the casino would retain the smokestack and iconic New Bedford Gas & Edison Light Complex building on the property. KG New Bedford has committed to investing $10 million in a public harbor walk and pedestrian walkover to connect the casino with the historic district downtown.

Downtown’s Zeiterion Performing Arts Center is identified as the impacted live entertainment venue under the gaming act’s eligibility requirements, and KG New Bedford will provide cross-marketing to it and to existing stores and restaurants in the area.

KG New Bedford has signed an agreement with the local labor union specifying that 20 percent of the construction workforce will be union. And an affirmative action program, also part of the gaming act’s requirements, also is included in the agreement between the city and KG New Bedford.

In exchange for a $12 million payment-in-lieu-of-taxes, the city agrees not to request additional fees or costs for improvements to schools, police or fire services and infrastructure. A $4.5 million preliminary economic regeneration payment to the city was agreed on as required by state law.

Brownfield cleanup The former NSTAR site was used historically by the New Bedford Gas & Edison Light in the late 1880s. The plant manufactured gas until the 1960s. A portion of the property also processed tar, from the 1930s to 1960s, with dockage to offload coal tar from barges for processing.

When seepage of contaminants into New Bedford Harbor was identified in 1996, NSTAR began a site investigationand remediation plan under Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection review. By 2012, steel sheet piling, dredging and capping had contained the contaminants found in the slip areas and bottom sediments, according to state officials.

But the remediation plan only contained the existing onsite material from escaping into the harbor. The site was found to have significant levels of tar, coal tar, fuel oil, cyanide, lead paint, asbestos and mold. KG New Bedford has committed to a $50 million cleanup of those remaining contaminants.

Once KG New Bedford completes the equity verification process, which is expected to be completed by May 4, as part of the Gaming Commission’s licensure requirement, it will move forward with setting up public forums on the referendum.

In addition to other costs, KG New Bedford has agreed to foot the estimated $90,000 special election for the ballot question. According to the Election Commission, the election requires some 200 workers at 36 polling sites.

“As hard as we worked, now it’s left up to our constituency,” Ward 2 Councilman Steve Martins said. “Whichever way they vote, they must come out and vote.”

Charles Chieppo: The wrong person to head Boston schools

BOSTON

Massachusetts Education Secretary Matthew Malone has made no secret about wanting to become the next superintendent of Boston Public Schools.

“I’ve been training for this job all my life,” Malone told The Boston Globe. “It’s my calling.”

But there is precious little in Malone’s background to support that claim.

Before becoming secretary of education, Malone was superintendent in Brockton, the commonwealth’s fourth-largest school district. During his 2009-2012 tenure, the percentage of elementary- and secondary- school students scoring proficient or advanced on MCAS fell at every grade level but one. Eighteen months before his contract expired, the city’s school committee informed him that he would not be rehired.

Malone, who is no shrinking violet, also told The Globe that he’s “in the arena and willing to fight and die for these kids.” Not only is there little to support that claim, but there is extensive evidence indicating it is blatantly false.

Brockton is the largest city in Massachusetts that doesn’t have a charter school. Toward the end of his tenure there, Malone’s primary focus seemed to be on ensuring the rejection of a charter school that had been proposed for the city.

The school was to be operated by Sabis, a charter-school-management company that operates two inner-city schools recently opened in Holyoke and Lowell, and a third in Springfield that has been operating for nearly 20 years. Every graduate in the history of the Springfield school has been accepted to college and it has repeatedly been recognized by Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report as one of the nation’s best high schools.

Sabis Springfield has a four-year graduation rate of more than 90 percent compared to less than 70 percent at Brockton High. On 2012 MCAS English tests, two-thirds of Sabis Springfield students scored advanced or proficient; less than half did so in Brockton. On math MCAS tests, the majority of Sabis students scored advanced or proficient compared to just over one-third in Brockton.

So did Malone “fight and die” for Brockton’s kids?

Hardly. Emails obtained by Pioneer Institute (which I am affiliated with as a senior fellow) show that he used his office and city resources to do things like craft a less-than-clever “$ABIS” logo and use his political contacts to kill the charter proposal. As Malone wrote in an email to the Brockton School Committee and several of his staff members, “It helps to have friends at [the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education].”

It worked. The Brockton charter school proposal was rejected, and the city is worse off as a result.

Perhaps Matthew Malone’s application to be superintendent of Boston Public Schools should read that he is “willing to fight and die for these kids” — once it’s clear that the status quo is protected and the jobs of every adult in the system are secure.

Charles Chieppo is the principal of Chieppo Strategies, a public-policy writing and communication firm.

Rebuilding mills as communities

Fall River, "The Spindle City. In the foreground is the Algonquin Mill, for which there are big plans and high hopes.

Photo by TOM PATERSON

The Mills Alliance, which wants to protect and reuse Massachusetts's old mills -- many built in the 19th Century -- for economic, environmental, sociological and, of course, aesthetic reasons is a terrific resource for developers, owners, public officials and local residents in general who see the big long-term advantages of saving these old stone and brick structures, which could last for many hundreds of years more if they are taken care of. Major centers for this beautiful and utilitarian architecture include Lowell, Fall River, New Bedford, Brockton (the former shoe-making center) and Taunton.

While the alliance is now focusing on Southeastern New England, members see it eventually expanding its activities to include mills in all of southern New England and perhaps beyond in the Northeast. (Upstate New York and parts of Pennsylvania have some beauties.)

Many of them are highly adaptable for residential space and commercial activities, including assembly. Yes, some can be turned into real factories again! These buildings are so large that people can work on one floor, live on another and shop in stores on a third (presumably usually the ground floor). These are some of the ways in which saving them reduces sprawl.

The roofs of some of these mills are big enough to support commercially viable vegetable farms. (See the Brooklyn Grange as an example.)

And now Mills Alliance people are making a push to teach people that the carbon footprint of tearing them down is heavy.

The alliance says: "We believe that in an era of increasing population, decreasing economic stability, increased competition for natural resources, generally rising prices and abundant pressures on all of us to live smartly, economically and in harmony with our environment, mills offer great hope and possibility by their central locations and adaptive reuse.''

It goes on:

"Pull our mills into the 21st Century by the embrace of new technology, the promotion of tax incentives for recapitalization, and encouragement of mixed-use, live/work communities that will provide housing and employment and an agreeable, sustainable quality of life in our beleaguered industrial centers.''

Quite right.