GOP mulls ‘Slayveree’; See haunting bas relief in Boston

From the National Park Service:

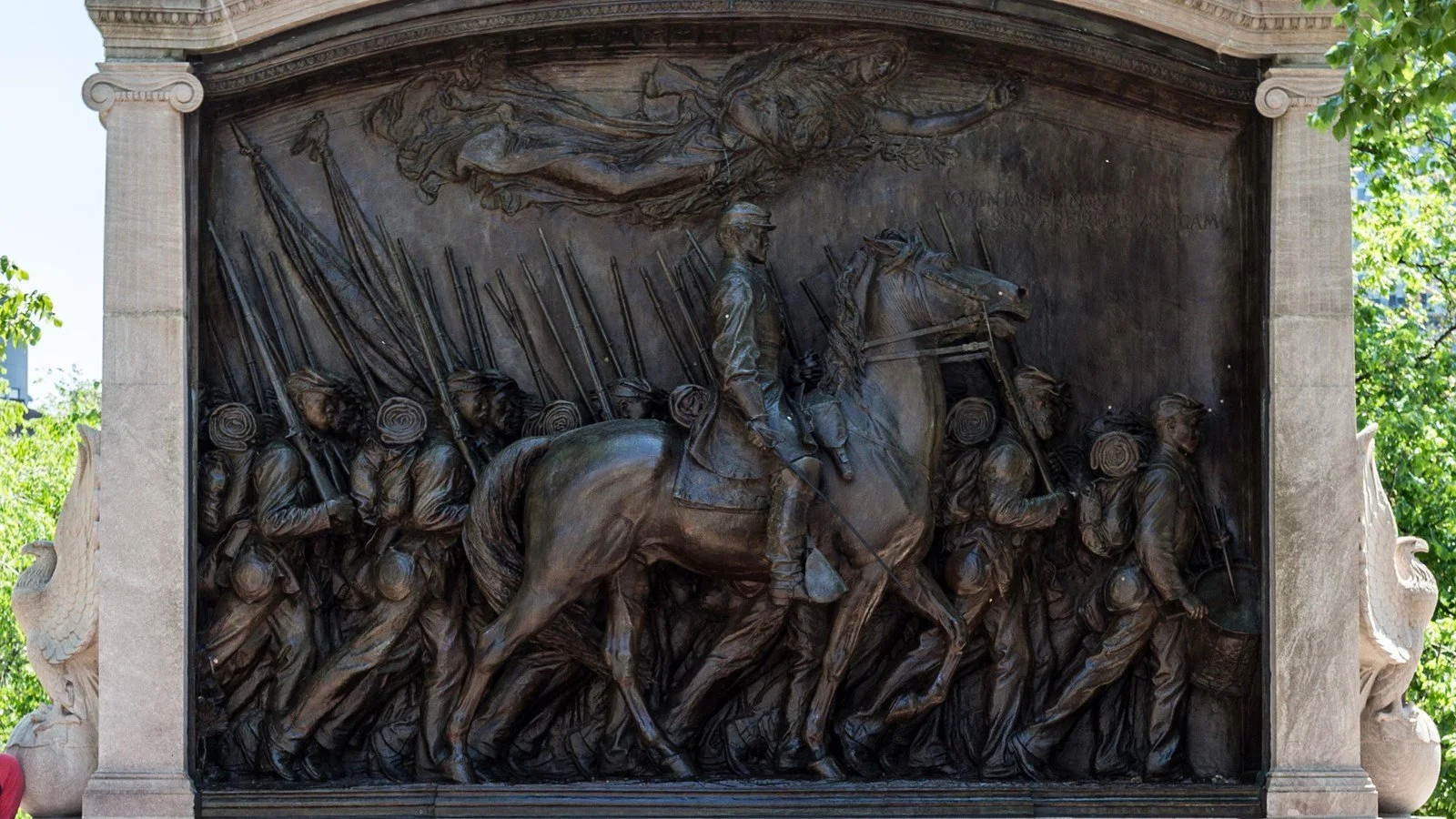

The Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial, installed in 1884, a haunting bronze bas relief on the Boston Common, and created by famed sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, commemorates the first Black regiment from the North in the Civil War. Although African Americans served in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, Northern racist sentiments kept African Americans from taking up arms for the United States in the early part of the Civil War. However, a clause in Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation allowed for the raising of Black regiments. Gov. John Andrew soon created the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry. He chose Robert Gould Shaw, the son of wealthy abolitionists, to serve as its colonel. Notable abolitionists including Frederick Douglass and local leaders such as Lewis Hayden recruited men for the 54th Regiment. African Americans enlisted from every region of the north, and from as far away as Canada and the Caribbean.

Through their heroic, yet tragic, assault on Fort Wagner, S.C., on on July 18, 1863, in which Shaw and many of his men died, the 54th helped erode Northern public opposition to the use of Black soldiers and inspired the enlistment of more than 180,000 Black soldiers into the Union’s forces.

The front of Linden Place, the Bristol, R.I., mansion built in 1810 for infamous slave trader (and other “cargoes”), privateer and ship owner Gen. George DeWolf and designed by architect Russell Warren. The mansion now operates as a historic house museum.

— Photo by Bbucco/ Tiffany Axtmann Photography

The joy and pain of shrinkage

Big enough

— Photo by Cavajunky

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Many people at the end of the year reflect on whether they should make a major life change. This might include simplifying by downsizing where they live.

So I recommend Dr. Edward Iannuccilli’s latest book of essays, Essays on the Art and Pain of Downsizing. (He’s a friend, but no, I get no kickbacks for this plug.)

Of course, many older people, such as Dr. Iannuccilli, who lives in beautiful Bristol, R.I., downsize in part because of their stage of life. But there are good reasons for others to do so. You save on fuel, electricity, taxes and insurance and you’re disciplined to get rid of stuff, which can feel liberating. (Do some people have so much stuff that it acts as insulation, saving fuel in the winter?)

In 1980, the median size of a new house in the U.S. was 1,595 square feet. That ballooned to 2,386 square feet by 2018, with fewer people living in these houses. Obviously, the bigger the house, the bigger the purchase price and maintenance costs; the latter tend to be alarmingly unpredictable.

Town hall and Civil War memorial in Bristol, R.I.

Frank Carini: Working to reduce environmental impact of ocean racing sailboats

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

While the United States flails about trying to reduce its enormous share of world-altering climate pollution, one part of the transportation/recreational sector is routinely ignored: boating.

Yachting and sailing are steadily gaining in popularity, so an urgency to act is essential if greenhouse-gas emissions are to be significantly reduced.

Yes, sailing burns little fossil fuel, but the resources consumed to build some of these vessels is swelling.

For instance, over the past decade, the carbon footprint of 60-foot International Monohull Open Class Association (IMOCA) racing boats has grown by nearly two-thirds, from 340 to 550 tons — the equivalent of driving an average car 1.4 million miles, according to the 11th Hour Racing Team.

“This is an overall trend we see in pretty much any industry, driven by performance we have accelerated too fast in the wrong direction, and are only just waking up to reality,” according to Damian Foxall, sustainability program manager for the 11th Hour Racing Team. “The need to reduce our emissions in the marine industry is urgent — 50% by 2030, and that’s just eight years away. We are far away from that right now.”

The 11th Hour Racing Team is sponsored by 11th Hour Racing, a Newport, R.I.-based nonprofit that works with the sailing community and maritime industries to “advance solutions and practices that protect and restore the health of our ocean.”

Late last year the team published a report about the importance of building a more sustainable ocean racing boat and better understanding the industry’s environmental impact. It showed performance doesn’t need to be sacrificed to build a more environmentally friendly boat.

“Business as usual is no longer an option. While the performance sailing sector and much of the leisure marine industry is geographically centered in the global North and a few other well-off regions, we live in a fragile bubble of prosperity,” according to the report. “This alternative reality does not reflect either the reality for most of the world’s citizens, or the availability of the earth’s resources.

“Inherently tied to the ongoing growth of global economies, we would need 1.7 Earths each year just to maintain the situation for the average global citizen. Scaled to the typical lifestyles associated with the marine industry this is more like 5+ Earths each year: a growing annual debt,” the report says.

The 128-page report includes a detailed study of material life cycles and alternative composites, such as flax to replace ubiquitous virgin carbon fiber. About 80 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in a boat build are associated with the use of composite materials, most notably carbon fiber, which is perfect for racing because it is light and stiff. Reducing the use of this material and others would significantly lessen climate emissions tied to the building of a new racing boat, according to the 11th Hour Racing Team.

In fact, the 11th Hour Racing Team and its partners are advocating for radical change across the marine industry to transform the way boats are built. They believe that only by “prioritizing sustainability along with performance, can the marine industry take urgent action to fight climate change.”

Foxall recently told ecoRI News that sustainable sourcing and using as much renewable energy as possible are the two biggest things racing teams can do right now to lower their carbon footprints.

The 11th Hour Racing Team, for instance, now leases an electric support vessel during races, which has lowered climate emissions from both a transportation and manufacturing perspective.

Foxall said rule changes would require sailing teams to incorporate more sustainable materials into their design and build. He noted, for example, reused carbon fiber is mostly avoided because the virgin material makes for better performance. But if rules required every team to use recycled fiber, no team would have an advantage.

“In our sport, rules define what the boats are … as much as one team or a couple of teams or even an event might want to improve the footprints, that cannot happen until the rules incentivize it,” Foxall said. “And the rules for the longest time have incentivized performance, whether it is carrying more sacks of coal or corn from Australia to Europe or transporting more people from Europe to North America or now racing faster and going faster through the water. It’s all about performance.”

He added the sport can no longer “just make decisions based purely on performance. We need to be taking into account the direct and indirect impacts” on the environment.

The December report recommends establishing minimum standards on sourcing, energy, waste, and resource circularity; defining a threshold for carbon emissions based on life cycle assessment (LCA) data; incentivizing the marine industry to use its inherent capacity for innovation to focus on sustainability; and setting an internal price for carbon emissions.

Amy Munro, sustainability officer for the 11th Hour Racing Team, noted the building of a racing boat is a complex process involving a number of stakeholders, materials, and components.

“You need to break it down in detail to fully understand what are the major impacts,” according to Munro. “This is why we have meticulously measured the impact of every step in the design and build process of our new boat and conducted a life cycle analysis that helps to uncover underlying issues.”

Last month, Charlie Enright, 11th Hour Racing Team skipper, spoke at the U.N.-supported One Ocean Summit in Brest, France, to highlight key findings of the organization’s “Sustainable Design and Build Report,” notably the importance of industry-wide collaboration to push sustainable innovation to align with the Paris Agreement.

“Within our sport, for too long we have chased performance over a responsibility for the environment and people,” the Bristol, R.I., native told an audience of experts, politicians, activists, and decision-makers. “We must work together to reduce the impact of boat builds, adopt the use of alternative materials like bio-resins and recycled carbon, lobby for a change to class and event rules to reward sustainable innovations, and support races and events that are managed with a positive impact on our planet and people.”

Foxall noted about 50 percent of sailors are onboard when it comes to making their sport more sustainable. He said it is their responsibility to bring the others up to speed about the impacts of the climate crisis.

In an email to ecoRI News, Enright noted the sport’s awareness of climate and environmental issues is “definitely increasing.” He said big events such as The Ocean Race and the Transat Jacques Vabre have “strong sustainability policies” in place, including plastic-free race villages, onboard waste calculation initiatives, and efforts to educate teams and fans about these matters. “This is relatively new in our sport.”

The Ocean Race also runs an ocean science program in partnership with 11th Hour Racing, collecting data on water temperature, salinity, and other potential climate change impacts. The Transat Jacques Vabre uses the 11th Hour Racing Team’s Sustainability Toolbox, which, among other things, commits to efforts to limit waste, use renewable energy and reduce emissions wherever possible, as a framework for its own sustainability program.

“Of course there are those who need a bit more convincing on the importance of it,” Foxall said. “But, quite frankly … kids coming home from school today know what the issue is.”

In 2019, greenhouse-gas emissions from ships and boats in the United States alone totaled 40.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. Globally, bulk carriers are the main source of shipping/boating climate emissions. Some 90 percent of world trade is carried across the world’s oceans by some 90,000 marine vessels. Carbon dioxide emissions from these vessels are largely unregulated.

Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) did adopt exhaust emission standards for marine diesel engines installed in a variety of marine vessels, ranging in size and application from small recreational boats to large ocean-going ships.

While the shipping industry is responsible for a significant proportion of global climate emissions — if global shipping were a country, it would be the sixth-largest producer of greenhouse gases behind China, the U.S., Russia, India and Japan — the climate impacts of the recreational powerboat industry, most notably yachts, are considerable.

The propulsion systems on many yachts are arguably the least-efficient modes of transportation ever devised. The typical 40- to 50-foot yacht guzzles fuel.

U.S. recreational boaters spend about 500 million hours annually cruising fresh and salt waters. In 2010, more stringent EPA emissions standards for marine engines, both in-board and outboard, went into effect. But, unlike cars, private boats are not inspected. They can be checked by the Coast Guard or law enforcement, but there is no annual emissions check.

Many recreational boats and some jet-propelled watercraft have two-stroke engines. Conventional two-stroke engines produce about 14 times as much climate pollution as four-stroke engines.

Last year new U.S. powerboat sales surpassed 300,000 units for the second consecutive year, closing 2021 about 6 percent below record highs in 2020 and some 7 percent above the five-year sales average, according to the National Marine Manufacturers Association. In 2020, annual U.S. sales of boats, marine products and services totaled $49.3 billion, up 14 percent from 2019.

The oceans play an essential role in keeping atmospheric carbon dioxide in balance by absorbing about 30 percent of the CO2 that is released, from all sources. This blue carbon sink, however, has been working overtime since the Industrial Revolution began belching fossil fuels into the atmosphere.

The ocean, though, can only swallow so much of this colorless gas. When carbon dioxide is absorbed by seawater, chemical reactions occur that increase the acidity of the water through a process known as ocean acidification.

Acidifying marine waters are bad news for marine life with calcium carbonate in their shells or skeletons, such as oysters, corals, crabs, scallops, and mussels. Studies have found that more acidic salt waters make it more difficult for them to develop their hardened protection.

As of early last month, the recorded amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was a tick away from 418 parts per million (ppm) — well beyond the 350 ppm that climate scientists have deemed safe for humans, never mind most of the planet’s other living inhabitants.

“While the situation is extremely urgent and ‘business-as-usual’ is clearly no longer an option, it is still technically possible to close your eyes and look away,” Enright wrote. “This is why we have to act now and we have to create our own pressure. What we need is a radical change and one of the most important parts here is that the marine industry works together to achieve it.”

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter of ecoRI News.

Azzam, at 592.5 feet, was the longest superyacht, as of 2020.

— Photo by ChrisKarsten

Nothing good about being a good loser?

Red Auerbach on the bench next to rookie Bill Russell during a game at the old Boston Garden, Dec. 26, 1956. Bob Cousy can be seen in the background.

“Show me a good loser, and I’ll show you a loser.’’

— Arnold “Red’’ Auerbach (1917-2006), legendary and highly successful head coach (1950-1966), and then general manager, of the Boston Celtics.

xxx

“Part-time information and full-time opinions can be very dangerous.’’

{Even in sports?}

— Chris Berman (born 1955), a sportscaster for ESPN (originally short for Entertainment and Sports Programming Network) virtually since ESPN was launched, in 1979, as one of the first major cable-TV networks. It has been based since its founding in Bristol, Conn.

ESPN’s palatial headquarters, in Bristol, Conn.

— Photo by Jkinsocal

American Clock and Watch Museum, in Bristol, which, like Waterbury, Conn., was a major maker of clocks.

Susan Jaffe: Designating 'essential support' people for nursing-home residents

From Kaiser Health News (kaiserhealthnews.org)

After COVID-19 hit Martha Leland’s nursing home — Sheridan Woods Health Care Center, in Bristol — it logged 28 fatalities; last year, she and dozens of other residents contracted the disease while the facility was on lockdown.

“The impact of not having friends and family come in and see us for a year was totally devastating,” she said. “And then, the staff all bound up with the masks and the shields on, that too was very difficult to accept.” She summed up the experience in one word: “scary.”

But under a law that Connecticut enacted in June, nursing-home residents will be able to designate an “essential support person” who can help take care of a loved one even during a public health emergency. Connecticut legislators also approved laws this year giving nursing-home residents free internet access and digital devices for virtual visits and allowing video cameras in their rooms so family or friends can monitor their care.

Similar benefits are not required by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the federal agency that oversees nursing homes and pays for most of the care they provide. But states can impose additional requirements when federal rules are insufficient or don’t exist.

And that’s exactly what many are doing, spurred by the virus that hit the frail elderly hardest. During the first 12 months of the pandemic, at least 34 percent of those killed by the virus were residents of nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, even though they make up fewer than 1 percent of the American population. The vaccine has since reduced virus-related nursing-home deaths to about 1 in 4 covid-related fatalities in the United States, which have risen to more than 624,000, according to The New York Times’s case tracker.

“Part of what the pandemic did is to expose some of the underlying problems in nursing homes,” said Nina Kohn, a professor at Syracuse University School of Law and a distinguished scholar in elder law at Yale Law School. “This may present an opportunity to correct some of the long-standing problems and reduce some of the key risk factors for neglect and mistreatment.”

According to a review of state legislation, 23 geographically and politically diverse states have passed more than 70 pandemic-related provisions affecting nursing home operations. States have set minimum staffing levels for nursing homes, expanded visitation, mandated access for residents to virtual communications, required full-time nurses at all times and infection control specialists, limited owners’ profits, increased room size, restricted room occupancy to two people and improved emergency response plans.

The states’ patchwork of protection for nursing home residents is built into the nation’s nursing home care regulatory system, said a CMS spokesperson. “CMS sets the minimum requirements that providers need to meet to participate with the Medicare/Medicaid programs,” he said. “States may implement additional requirements to address specific needs in their state — which is a long-standing practice — as long as their requirements go above and beyond, and don’t conflict with, federal requirements.”

Julie Mayberry, an Arkansas state representative, remembers a nursing home resident in her district who stopped dialysis last summer, she said, and just “gave up” because he couldn’t live “in such an isolated world.”

“I don’t think anybody would have ever dreamed that we would be telling people that they can’t have someone come in to check on them,” said Mayberry, a Republican and the lead sponsor of the “No Patient Left Alone Act,” an Arkansas law ensuring that residents have an advocate at their bedside. “This is not someone that’s just coming in to say hello or bring a get-well card,” she said.

When the pandemic hit, CMS initially banned visitors to nursing homes but allowed the facilities to permit visits during the lockdown for “compassionate care,” initially if a family member was dying and later for other emergency situations. Those rules were often misunderstood, Mayberry said.

“I was told by a lot of nursing homes that they were really scared to allow any visitor in there because they feared the state of Arkansas coming down on them, and fining them for a violation” of the federal directive, she said.

Jacqueline Collins, a Democrat who represents sections of Chicago in the Illinois Senate, was also concerned about the effects of social isolation on nursing home residents. “The pandemic exacerbated the matter, and served to expose that vulnerability among our long-term care facilities,” said Collins, who proposed legislation to make virtual visits a permanent part of nursing home life by creating a lending library of tablets and other devices residents can borrow. Gov. J.B. Pritzker is expected to sign the measure.

To reduce the cost of the equipment, the Illinois Department of Public Health will provide grants from funds the state receives when nursing homes settle health and safety violations. Last year, Connecticut’s governor tapped the same fund in his state to buy 800 iPads for nursing home residents.

Another issue states are tackling is staffing levels. An investigation by the New York attorney general found that covid-related death rates from March to August 2020 were lower in nursing homes with higher staffing levels. Studies over the past two decades support the link between the quality of care and staffing levels, said Martha Deaver, president of Arkansas Advocates for Nursing Home Residents. “When you cut staff, you cut care,” she said.

But under a 1987 federal law, CMS requires facilities only to “have sufficient nursing staff to attain or maintain the highest practicable … well-being of each resident.” Over the years, states began to tighten up that vague standard by setting their own staffing rules.

The pandemic accelerated the pace and created “a moment for us to call attention to state legislators and demand change,” said Milly Silva, executive vice president of 1199SEIU, the union that represents 45,000 nursing home workers in New York and New Jersey.

This year states increasingly have established either a minimum number of hours of daily direct care for each resident, or a ratio of nursing staff to residents. For every eight residents, New Jersey nursing homes must now have at least one certified nursing aide during the day, with other minimums during afternoon and night work shifts. Rhode Island’s new law requires nursing homes to provide a minimum of 3.58 hours of daily care per resident, and at least one registered nurse must be on duty 24 hours a day every day. Next door in Connecticut, nursing homes must now provide at least three hours of daily direct care per resident next year, one full-time infection control specialist and one full-time social worker for every 60 residents.

To ensure that facilities are not squeezing excessive profits from the government payment they receive to care for residents, New Jersey lawmakers approved a requirement that nursing homes spend at least 90 percent of their revenue on direct care. New York facilities must spend 70 percent, including 40 percent to pay direct-care workers. In Massachusetts, the governor issued regulations that mandate nursing homes devote at least 75 percent on direct-care staffing costs and cannot have more than two people living in one room, among other requirements.

Despite the efforts to improve protections for nursing home residents, the hodgepodge of uneven state rules is “a poor substitute for comprehensive federal rules if they were rigorously enforced,” said Richard Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition, an advocacy group. “The piecemeal approach leads to and exacerbates existing health care disparities,” he said. “And that puts people — no matter what their wealth, or their race or their gender — at an even greater risk of poor care and inhumane treatment.”

Susan Jaffe is a reporter at Kaiser Health News.

Jaffe.KHN@gmail.com, @SusanJaffe

Black or white only

Nathanael Herreshoff climbing aboard Defender in 1895; Herreshoff designed five successful America’s Cup defenders in 1993-1920, including Defender.

-- Photo by John S. Johnston

“There are only two colors to paint a boat, black or white, and only a fool would paint a boat black.’’

— Nathanael G. Herreshoff (1848-1938), famed naval architect. He was born and died in Bristol, R.I. He died on June 2, 1938, thereby missing the great hurricane that wrecked the Herreshoff boatyard in Bristol on Sept. 21 of that year.

Biscuits and kittens in Vt.

Main Street in Bristol, Vt., at the western edge of the Green Mountains

“Even my children, though born here, would not be called Vermonters by most members of long-time Bristol {Vt.} families. (My neighbors might well respond, if I put the question to them, with the old Vermont joke: If the cat has kittens in the oven, does that make them biscuits?)’’

—- John Elder, in Reading the Mountains of Home (1971)

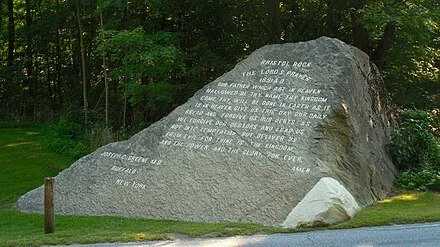

Lord’s Prayer Rock in Bristol

Todd McLeish: A proposal for 'freedom lawns'

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Few people put much thought into the soil beneath their feet, but Loren Byrne does. A professor at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, R.I., Byrne is an expert on urban soil ecology, and he worries that humans are changing the structural integrity of soils in urban environments and limiting the ability of plants and animals to live in and nourish the earth.

“Soil is easily overlooked and taken for granted because it’s everywhere,” he said. “We walk all over it and think of it as dirt that we can manipulate at our will. But the secret of soil is what’s happening with soil organisms and what’s happening with their interactions below ground that help regulate our earth’s ecosystems.”

Byrne contributed a chapter about urban soils to a report, State of Knowledge of Soil Biodiversity, issued last year by the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization. He discussed how the ecology of the soil changes as it is compacted during construction, paved over, chemically treated for lawns, and dug up and carried away.

“The main takeaway is that urbanization can potentially harm biodiversity, but our biggest current threat is ignorance,” he said. “We don’t understand enough about soil biodiversity in urban environments, so we may not be able to manage it in ways to provide the benefits that are possible.”

Soil is the foundation for terrestrial life, according to Byrne. It’s the medium in which plants are grown and it regulates the nitrogen cycle, sequesters carbon, and manages the flow of water. He said soils are fascinating because they contain the full range of life, from single-celled bacteria and fungi to animals of all varieties.

“If you’re patient enough to get down on your hands and knees and pull up some soil, you’ll see mites, springtails, isopods, millipedes, centipedes, spiders, ants, beetles,” Byrne said. “Some of them have negative popular connotations, but ecologically, if we can see them as having value, then that will help us maintain more sustainable landscapes.

“Changing our perspectives of what these organisms are doing in the ecosystem is important. They perform beneficial functions, like decomposition. I tell my students that if it wasn’t for this whole suite of biodiversity in our soils, we’d literally be up to our necks in dead stuff.”

Although it may seem counterintuitive, Byrne said urban soils contain the full range of biodiversity that is found in natural soils, and some research shows that they contain more organisms and a greater diversity than agricultural soils.

“A lot of urban habitat types, like lawns and little forest patches, are perennial, so they don’t face the same level of annual disturbance as agricultural fields,” he said. “And they have more organic matter in them, so that allows the food web to become more complex. Urban soils are home to a lot of organisms.”

He noted, however, that there is also a massive volume of degraded soil in urban areas that is compacted, trampled, over-fertilized, and removed and replaced with lower quality soil.

“It’s a very interesting dichotomy,” Byrne said. “There are some high-quality soils and other locations that have been severely negatively impacted where we would want to somehow improve them.”

How to improve degraded soils is the topic of Byrne’s latest research. Decompacting the soil and remediating pollution are important steps, but the key is the addition of organic matter.

“There’s been a wide diversity of organic matter sources that have been investigated, from basic garden compost to sewage sludge to bio-char, which is a burned organic matter that, when added to soil, provides good surfaces for microbes to live on,” he said. “But you have to be very careful about what you’re using and in what contexts and the source, because not all organic matter is the same.

“A lot of research has shown that adding organic matter will help remediate the soils in various ways. Organic matter holds onto water, so it helps with water issues, for instance. But in locations that are already prone to water-logging, adding organic matter could be a bad thing. So context matters. You need to be familiar with site specific issues to come up with a good management plan.”

Byrne focuses a great deal of his research attention on lawns, which he calls a “human-created ecosystem.” While he noted that a lawn provides a nice place for a picnic and is better than pavement, he said installing a lawn is the least biodiverse way of improving urban landscapes.

“The goal with a lawn is often one grass species that’s bright green and isn’t growing or reproducing, which is the exact opposite of what life wants to do,” he said. “In the grand scheme of all life, a place becomes more diverse over time, it grows and reproduces, and humans are trying to stop all of that in a lawn.

“The problem isn’t so much the lawn itself as the monoculture, pesticide-managed lawn. A lot of what ecologists advocate is a more biodiverse lawn where we let the so-called weeds grow and let the grass grow a little taller. That’s good for the soil ecosystem because a higher variety of plants and no chemical pesticides will allow more soil organisms to thrive.”

To create a more sustainable urban landscape, Byrne advocates for what some have called “freedom lawns” — a mowed lawn that maintains a high diversity of grasses and weeds and good soils.

“If we can convince people that it’s more patriotic to shift to freedom lawns, it will be more sustainable,” he said. “And if we can shrink the area of lawn by creating more biodiverse habitat through shrubs and wildflowers, that’s another step toward sustainability and biodiversity.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Grace Kelly: The bumpy road to R.I.’s East Bay Bike Path

Facing south near the East Bay Bike Path's southern terminus, in Bristol

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

“These days it’s hard to find someone who thinks creating the East Bay Bike Path was a foolish idea.” So begins a Providence Journal article written in 1999 by Sam Nitz, which chronicled the bike path’s beginnings and eventual completion.

The same could be said in 2020, a year when a pandemic forced people to get creative with their time. They took to the outdoors when the weather turned warm, with many dragging a set of wheels to a Rhode Island bike path that runs from Providence to Bristol.

I cruised along this path myself, dodging hand-holding couples, bold squirrels, and the occasional toddling roller-skater.

A map of the East Bay Bike Path from a 1984 pamphlet. Construction of the trail took place from 1987-92.

While looking at the path today might give the impression that it was a beloved idea all along, as Nitz noted in his article, “the path’s beginnings in the early 1980s were fraught with controversy and rancorous political debate.”

The 14.5-mile stretch of asphalt was hardly a shoo-in. In fact, it was met with raucous opposition, German shepherds, and even a letter to a high-level staffer of President Reagan begging for federal intervention.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The story of the East Bay Bike Path starts with an old stretch of railroad that connected Providence to Bristol, with stops in Riverside and Warren and a connecting line that went to Fall River, Mass. It was a handsome railway, with postcards and old photos depicting almost modern-looking platforms and stations — one particular image of the rail near the future Squantum Association, a private club in East Providence, could be from the 2000s.

But as automobiles began to capture the American spirit, the railway slowly faded into disuse and the passenger line ended in 1938. In 1976, the State of Rhode Island acquired the right of way for the old Penn Central line, the section that ran from East Providence to Bristol.

It would also be automobiles that would inspire Bristol state Rep. Thomas Byrnes Jr. in the late 1970s, to lead the charge to create a bike path on the old Penn Central line.

“When I started at the State House in ’78, the oil shortage was … tough,” said Byrnes in a 2002 interview with his daughter Judith. “People were driving bombers around and they were having a hard time keeping their cars filled with gas. So, they were talking about looking into alternative means of transportation to cut our use of oil.”

And one idea that came up: bicycles.

In the ’70s, the United States experienced a bicycle boom, with some 64 million Americans using bicycles regularly. A 1971 article in Time magazine noted that America was having “the bicycles biggest wave of popularity in its 154-year history.”

So, at the time when Byrnes started thinking about alternative methods of transportation, bicycles were everywhere, and other states such as Maryland were starting to investigate turning old railways into bike trails.

In March 1980, Byrnes and Matthew Smith, who was the Rhode Island speaker of the House at the time, wrote a joint bill that called for a study of bicycling as an alternative form of transportation and as an energy saver. The idea of the East Bay Bike Path was born.

What happened next was years of pushing through heated resistance.

“There was a lot of opposition, a lot of opposition,” said Robert Weygand, who was the chairman of the East Providence Planning Board in the early ’80s, and who later went on to be a U.S. congressman and Rhode Island lieutenant governor. “In every community there were people that came out opposed to it.”

Weygand became involved in the project through his work on the East Providence Planning Board and later as part of a group called Friends of the Bike Path. He saw its creation as a way to help restore East Providence’s once-rich history of activities and attractions along the water.

“We heard about what Tom [Byrnes] had been proposing for a bicycle trail along the railroad tracks … and we were in East Providence, which had a long history of having amusement parks and various venues along the railroad tracks,” Weygand said. “So we were interested in trying to reinvigorate the idea of having activities along the waterfront, which had been abandoned for a very, very long time.”

The East Bay Bike Path had plenty of fierce opposition, but had the support of the Rhode Island Department of Transportation and its then-director Edward Wood.

The wheels were now set in motion, and in 1982, Gov. J. Joseph Garrahy and the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (DOT), which was then led by Edward Wood, who died this year, threw their support behind the project and hired an engineering firm to research feasibility and design.

“The biggest thing that really helped us along the way was governor Joe Garrahy … he really embraced it,” Weygand said. “And also, there was a fella that was the head of the Department of Transportation, Ed Wood.”

But though Wood and Garrahy supported the project, many in their own circles were firmly against it.

“Even Wood at DOT ran into opposition by his own staff,” Weygand said. “They wanted to preserve the East Bay railroad track system … potentially for freight traffic and rail traffic … so his own staff was fighting him because they thought, if we give up the railroad tracks, we'll never get them back.”

Meanwhile, Byrnes, Weygand, a man named George Redman — you’ll find his name and portrait on the section of the bike path that crosses Interstate 195’s Washington Bridge — and a group of others were busy fighting their own battle on the ground to win the people of the five municipalities over on the idea.

“We constantly met, talked about different opportunities, did public hearings and meetings … and we’d get together periodically to share war stories about what was going on,” said Weygand, with a chuckle. “There was some real opposition. We had a public hearing in 1983 at the Barrington YMCA, and people were yelling and screaming and swearing at us, saying that all the criminals from Providence would use this bike path to come down and steal things from their homes. It was terrible.”

One vivid memory Weygand has of the resistance was when he helped organize a walk of the proposed area to give people a feel for what it could be like.

“One of the things that happened that day that we had this walk was, we had about 50 or so people go along the path … and in notifying all of the abutting owners, one of the owners was Squantum Club,” Weygand recalled. “We had invited them to join us along the way, and when we got to the Squantum Club, the manager was there with German shepherds and cars to prevent us from passing anywhere near their property.”

James W. Nugent, who was a member of the Squantum Association at the time, even went as far as to write a letter to James A. Baker III, a friend of his who was the chief of staff of President Reagan.

“At a time when the nation is looking for ways to cut expenditures and increase income, I thought it appropriate to call to your attention an expenditure that to me, and to many residents of Rhode Island, seems almost frivolous,” Nugent’s letter reads. “When there is publicity about people going hungry and dangerous federal deficits, the logic of expanding over $1 million on a bicycle path escapes me — especially when so many people along the route of the path object strongly to it. They fear increased vandalism and housebreaks from the transient traffic when their properties become more easily accessible.”

Nugent goes on to ask Baker to sway the federal government to withhold funds for the project.

Though opposition was strong, there were supporters who should not be discounted. One of them was Barry Schiller, who was the on the transportation committee of the environmental group Ecology Action.

In a 1984 letter to Wood, Schiller wrote, “This should be an ideal bikeway, scenic, safe and relatively flat that will become the pride of the East Bay.”

Schiller’s words were prophetic in some ways. Instead of being a so-called crime highway, the East Bay Bike Path has become a place where friends and families gather and exercise. Instead of negatively affecting home values, living near the bike path is considered an asset. It’s also inspired other Rhode Island municipalities to build their own bike paths; there are eight today, according to DOT.

In the end, the proponents won out, and on May 22, 1986 ground was broken at Riverside Square, and the East Bay Bike Path became a reality.

“It seems like a long time ago, but it really wasn’t,” Weygand said. “It was absolutely wonderful, breaking ground and seeing it constructed.”

Construction took place from 1987-92, and today when Rhode Islanders cruise by on its blacktop, many are likely unaware of all it took for it to get done. But those who were there, those who helped push it through, they remember.

“Every time I ride the East Bay Bike Path, it gives me the inspiration to keep going, because I knew it took persistence in the face of strong opposition to get it done,” Schiller said. “It’s a lesson for all of us to not give up.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News reporter.

Lindsey Gumb: Pandemic means now is the time to widen access to learning materials

Open Access logo, originally designed by Public Library of Science

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BRISTOL, R.I.

Residential college and university campuses across New England abruptly closed their doors last month during the COVID-19 outbreak, and while some schools were in session and students were asked to vacate, many others were on spring break and students were asked not to return. In both situations, students found themselves at home or in new environments where they waited to see how their education would progress online and remotely.

Among many variables associated with the chaos and stress of the pandemic, a lack of direct access to learning materials like textbooks has arisen as one of the major roadblocks to student learning in the era of COVID-19.

As a nation, we have continued to observe a sharp rise in textbook prices since 1977, which leaves many students enrolled at postsecondary institutions, public or independent, unable to afford the required learning materials for their courses. As a Band-Aid solution, students often rely on borrowing a copy of the book or material from a classmate or the campus library—options that became obsolete overnight when campuses closed and we entered this new world of social distancing and online learning and course delivery. When access barriers to learning materials like textbooks exist, either financial or circumstantial (as in the case of COVID-19), we know that students’ grades and academic trajectory suffer, and ultimately institutional retention can take a hit. Having been laid off from part-time jobs, denied unemployment and mostly left out of the COVID-19 stimulus package, college students have enough stress and anxiety right now—the last thing they should be worrying about is not having access to their textbooks. Enter OER (Open Educational Resources).

Are those “solutions” really OER?

Textbook prices are only part of the access barrier issue. As teaching and learning shifts fully online during the COVID-19 pandemic, educators have been forced to more closely consider and analyze how copyright restrictions set by publishers may limit their students’ access to these essential learning materials. The last few weeks have shown more than ever why true OER have significant value in ensuring students have access to their learning materials, because they are free and have licenses that allow for reuse and retention without limitation. This is not the case with publisher content like textbooks or the many online learning “solutions” they offer in which access is only semester-long, not in perpetuity like OER. These materials, even if offered free of charge by the publisher right now during the pandemic, will inevitably shuffle back behind a paywall at the end of the semester, disproportionately harming students affected by conditions out of their control brought on by COVID-19 (displacement, illness, caretaking responsibilities, etc.) and who may need to retake courses and need access to the materials again.

OER providers such as Lumen Learning, Saylor Academy and the Open Course Library have full online courses ready to be adopted and easily integrated into learning management systems with very little effort needed by faculty members. The content is customizable. Students have immediate, free access, and unlike publisher content, access to the content won’t be lost when the semester ends.

OER, however, is not and cannot be the blanket solution for ensuring students have access to their learning materials during a time like this. In fact, we’ve heard stories from across the region of institutions handing out technology and hotspots to help address the digital inequities that exist for so many students. The Community College of Rhode Island awarded nearly 700 students grants to acquire computers or gain internet access with an additional 61 iPads distributed to students who requested them. OER are primarily digital resources, and students need an Internet connection to at least initially download the resource onto a device. While they are free, OER will still require other institutional support systems to make sure our students have everything they need to equitably participate in their remote learning.

Freeing information

This isn’t just about students’ access to textbooks. Also at issue is the current publishing industry’s suppression of access to information. SPARC (the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Research Coalition) defines Open Access (OA) as the “free, immediate, online availability of research articles coupled with the rights to use these articles fully in the digital environment. OA ensures that anyone can access and use these results—to turn ideas into industries and breakthroughs into better lives.” The American Library Association and academic librarians have long been advocating for OA policies that remove barriers to scholarly, peer-reviewed research that are typically only accessible to those who have an active academic affiliation such as faculty, students, staff at colleges and universities. Institutions pay outrageous annual subscription fees on behalf of their community members to access this content, and those who have no affiliation pay a fee to access each article.

We’ve seen recently that many news organizations, such as The New York Times, Bloomberg News and The Atlantic, have removed the paywall on articles pertaining to COVID-19 so that the public has access to pertinent information that could potentially be lifesaving. OA fosters the same spirit except, instead of news, the information is peer-reviewed research, often generated by researchers through federal grant funding, aka “your tax dollars.” New research, particularly in the medical field, can have an immediate impact on public health. If that information is behind a paywall, only the privileged will have access to that potentially life-saving research. In January, a Washington Post article, Scientists are unraveling the Chinese coronavirus with unprecedented speed and openness, strongly illustrated this point. The genome sequence of the coronavirus was posted in an open access repository for genetic information and literally overnight, Andrew Mesecar, a professor of cancer structural biology at Purdue University, got a hold of it and started analyzing the DNA sequence. The immediate domino effect of having this information freely available has led to an international collaboration of scientists working together to aid in this public health crisis. Victoria Heath and Brigitte Vézina’s recent blog post for Creative Commons, Now is the time for Open Access Policies—here’s why, reminds us that “we must cooperate effectively to respond to an unprecedented global health emergency. The mantra “when we share, everyone wins” applies now more than ever.”

Robin DeRosa, director of the Open Learning & Teaching Collaborative at Plymouth (N.H.) State University, notes “there is a link between public health and Open. The open sharing of research and data can help us quickly collaborate to find medical solutions. Open pedagogy can help us involve our students in our fields’ responses to the pandemic and remind us that the digital divide can complicate remote learning. And OER can remove barriers for students and faculty who need to shift to more ubiquitously available resources. Open is about public infrastructure more than it is a set of free textbooks.”

For more on the basics and supporting research of OER, check out Open Matters: A Brief Intro and see additional resources at the Open Education and Open Educational Resources page on NEBHE’s website.

Lindsey Gumb is an assistant professor and the scholarly communications librarian at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, where she has been leading OER adoption, revision and creation since 2016, focusing heavily on OER-enabled pedagogy collaborations with faculty. She co-chairs the Rhode Island Open Textbook Initiative Steering Committee and the is Fellow for Open Education at the New England Board of Higher Education. She was awarded a 2019-20 OER Research Fellowship to conduct research on undergraduate student awareness of copyright and fair use and open licensing as it pertains to their participation in OER-enabled pedagogy projects.

(Editor’s note: New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is a former member of The New England Board of Higher Education’s Editorial Advisory Board.)

Clock tower at Roger Williams University, in Mount Hope Bay

— Phtoto by Notyourbroom

Lindsey Gumb: Leveraging Open Education

Source: Florida Virtual Campus (2019). 2019 Florida Virtual Campus Student Textbook & Course Materials Survey. Tallahassee, Fla.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

(Editor’s note: the author’s last name was misspelled in the headline in earlier editions; we regret the error.)

BOSTON

Late last September, I joined NEBHE as its Open Education Fellow to help build upon the grassroots efforts that have been underway for years in the Northeast aiming to lessen the burden that textbook costs place on higher education students and their families. Like so many of my colleagues doing this work day in and day out, I’m passionate about breaking down this very real barrier to student learning and success. Many people still have only a vague sense of “Open Education,” so I’d like to share some thoughts on what it is and why it matters.

I recently attended my third Open Education Global Conference in November 2019 at Politecnico di Milano in Milan, Italy. As always, I returned home from the conference, feeling inspired after engaging with colleagues from around the globe who are doing amazing things to make education more equitable and attainable for students.

The final conference keynote delivered by Cheryl-Ann Hodgkinson-Williams of the University of Cape Town in South Africa defined “open education” as an umbrella term that encompasses the products, practices and communities associated with this work. The common term that represents the products of Open Education is OER (Open Educational Resources).

OER has been defined by the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation as teaching, learning and research materials in any medium–digital or otherwise–that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions. OER include textbooks, ancillary material like quiz banks, lesson plans and syllabi, as well as full-course modules, multimedia such as video, audio and photographs, and any other intellectual property that can be protected by copyright. In short, OER can be simplified to Free + Permissions: free for the student to access and permission to partake in most if not all of the “5R” activities of reuse, revise, remix, redistribute and retain the resource at hand in perpetuity.

A learning resource may be low-cost or even free to the student, but not qualify as OER. For example, library-licensed content like e-books and scholarly journal articles are “free” for the student to access for a limited time, but those materials are still copyrighted, and in fact, are paid for by budgets supported by student tuition. This means that those resources are not actually free, and when students graduate, they lose digital access to these resources due to strict publisher agreements between the library and the publisher that stipulate only currently enrolled students be granted access. Traditional publishing is a business, after all.

Inclusive access

Another concept often conflated with OER is the “inclusive access” model. This is sweeping through our college bookstores today. Like OER, inclusive access models aim to ensure that all students have access to their learning materials on day one of class with the cost rolled into their tuition. Unlike with true OER, however, students lose access to these materials after the semester ends because of those copyright restrictions set by the publisher. Inclusive access models also strip students of their right under the “first sale doctrine” that so many took advantage of before the age of digital textbooks. This doctrine, codified at 17 U.S.C. § 109, states that an individual who knowingly purchases a legal copy of a copyrighted work (in this case, a textbook) from the copyright holder receives the right to sell it in the secondhand market. Single-semester access (like through the inclusive access model) doesn’t serve students who are taking courses in a sequence, studying for the GRE, changing careers, retaking a class or simply trying to be informed citizens throughout their lives, notes Nicole Finkbeiner, director of OpenStax at Rice University. True OER, in contrast, allow students to retain their learning content in perpetuity, serving students and learners of all ages and stages.

I often get asked: “Are the costs of textbooks really such a burden?” Yes, they are. Let’s take a closer look at the current landscape in higher ed that has educators rallying around openly licensed resources and their pedagogical benefits.

A 2018 survey of Florida’s higher education institutions showed that 64% of students aren’t purchasing the required textbook for their courses because of the high cost, 43% are taking fewer courses and 36% are earning a poor grade just because they were unable to afford the book.

A former student of mine who was a veteran was forced to wait six weeks until his stipend for books was distributed. That’s six weeks’ worth of readings, assignments, quizzes and exams for which he did not have his textbook to reference and help him prepare. Many might argue, “Just put the books on a credit card and pay it off later!” This simply isn’t an option for so many students who don’t have access to a credit card or don’t wish to take on more student debt. It’s also unrealistic for educators to determine if an assigned textbook is “affordable” or not for their students. What’s affordable for one student may be a burden for another, and it’s impossible to study from a book you can’t afford.

Academic hardships aren’t the only repercussions of expensive textbooks for our students. Many are forced to make tough decisions like skipping meals, falling behind on rent and other cost-of-living bills in order to afford their course materials. The staggering gap between state funding and tuition is putting an increasing burden on students and their families to come up with money to fund their education. While faculty have little to no control over tuition costs, they can exercise their academic freedom and elect to use OER to help alleviate the high cost of textbooks, which helps all students.

Saving students money on textbooks is critical. No student should have to decide between basic human needs like buying groceries or medications, paying rent and utility bills, going to the doctor or buying their textbooks. But we cannot pat ourselves on the back and stop at OER. My colleague on NEBHE’s Open Education Advisory Committee, Robin DeRosa at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire, put it best: “I don’t want to replace an expensive, static textbook with a free, static textbook.” She’s right. OER is not the end all be all solution, and we can’t stop there.

Not just a textbook case

Moreover, the work being done in OER extends far beyond advocating for free textbooks. Scholars and practitioners work together to continuously re-examine how to improve and build upon the existing successes, challenges and opportunities that accompany the products, practices and communities of Open Education.

Open Education has the potential to provide so many more pathways for engaged learning and innovative pedagogies, increase opportunities to intentionally build in UDL (Universal Design for Learning) practices that normalize accessibility, empower our students as content creators and contributors to the Knowledge Commons, and leverage equitable access to high-quality learning resources for all students, particularly historically marginalized groups.

Robin DeRosa and her students co-edited and published the Open Anthology of Earlier American Literature (with an open license, of course!) Students took on multiple tasks ranging from locating literature for inclusion, writing chapter introductions, and translating documents into modern English. While creating a free and openly licensed textbook for future students, DeRosa’s students also assumed the role of content creators and became published authors. The open license allows this student-created resource to be adapted and revised by other faculty and students, and interactive learning tools like Hypothes.is and H5P can be integrated into the textbook to remove that “static” element. (To view some other real examples of how educators are leveraging Open Education to encourage students take agency over their own learning experiences, I recommend checking out The Open Pedagogy Notebook, run by DeRosa and Rajiv Jhangiani, associate vice provost, open education at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in British Columbia.)

Deploying the products of Open Education, we have the potential to level the playing field and grant all students equitable access to high-quality, free postsecondary instructional materials.

Lindsey Gumb is an assistant professor and the scholarly communications librarian at Roger Williams University, in Bristol, R.I., where she has been leading OER adoption, revision and creation since 2016, focusing heavily on OER-enabled pedagogy collaborations with faculty. She co-chairs the Rhode Island Open Textbook Initiative Steering Committee. She was awarded a 2019-20 OER Research Fellowship to conduct research on undergraduate student awareness of copyright and fair use and open licensing as it pertains to their participation in OER-enabled pedagogy projects.

Chris Powell: Students lose a chance to learn about a huge religion

This is the Peaceable Oak, on Route 69 in Bristol, where Indians met to barter goods and colonists held town meetings when the nearby tavern proved too stuffy in summer.

Last week's hostility in Bristol, Conn., to a middle school teacher's plan to have a Muslim woman visit a world history class to discuss her religion and experiences, evoked the bigoted ignorance satirized in Woody Allen's movie Love and Death.

Child: What's a Jew?

Russian Orthodox priest: You never saw a Jew? Here -- I have some sketches. There are Jews.

Child: No kidding? They all have these horns?

Priest: No, this is the Russian Jew. The German Jew has these stripes.

The school superintendent canceled the Muslim woman's visit out of concern about security, since some of the hostility was threatening. Now there is talk about calling a townwide assembly on religious diversity. But as some Islamic leaders protested, the cancellation rewarded the threats. Surely Bristol's police could have stood by during the presentation -- and the need for security would have been a good lesson in itself.

Some people in Bristol said the public schools are not the proper place for religion. But religion is a huge part of history, and no one was to have been indoctrinated by the Muslim woman's presentation. For many students her visit might have been the first time they saw a Muslim in person rather than one on television being described as a terrorist. That too would have been a good lesson.

Yes, people are committing terrorism in the name of Islam, just as people have committed terrorism in the name of most other religions. Kids need to be shown the difference between the good guys and the bad guys.

Unfortunately many adults need to be shown too.

xxx

First Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy and the General Assembly's Democratic majority approved a new contract with the state employee unions that prevents state government from economizing with labor costs as much as it should.

Then a bipartisan majority of the legislature passed a state budget that, while not increasing taxes as much as Democrats wanted, directed the governor to find hundreds of millions of dollars in spending cuts that the legislature failed to specify.

So last week the governor did the specifying, and his cuts included social services and town aid, whereupon Democratic and Republican legislative leaders alike exploded in indignation.

A spokesman for the governor, Kelly Donnelly, shot back at the Senate Republican leader, Len Fasano, with criticism that could have been aimed at the Democratic leaders too.

"If the senator wanted to direct where these savings should come from," Donnelly said, "he could have passed statutory language with those details. He didn't do that. Rather, he took the much easier -- and much more politically safe -- route of accounting for the savings but leaving it to the governor to allocate them. ... He can still work with his colleagues to amend the budget, making specific cuts or perhaps raise taxes to avoid making these tough decisions. Until then he's just trying to have his cake and eat it too."

In fact, everybody at the Capitol is trying to have it both ways. The Democrats took care of the unions at the expense of everyone else, and then Republican and Democratic legislators alike posed as the friends of the taxpayer without taking responsibility for the cuts they required the governor to make.

Since the governor isn't seeking re-election next year, all the blame is being assigned to him when he deserves only half of it.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Robert Whitcomb: A civic celebration and a cruise

I enjoyed a piece of small-town Americana on Sept. 17, when I gave a talk at a luncheon meeting of the Bristol (R.I.) Rotary Club. Oh, for a renaissance of such civic organizations!

The club is part of Rotary International, which aims to bring mostly local business and professional leaders together to promote humanitarian service, boost ethics and encourage friendship and goodwill. The few dozen people at the meeting were thirtysomethings to eightysomethings; everybody seemed to have current or past professional or business connections.

I felt transported back to the Fifties. The meeting began with the Pledge of Allegiance, the singing of the National Anthem (with an 89-year-old lady playing the piano) and a nondenominational prayer. After lunch, attendees sang some pre-rock songs. Then came my talk, about the Islamic State, and smart questions.

It would be hard to find a nicer and more engaged group. Participating in such organizations has tended to decline in America in the last few decades. That’s sad, because they do a lot of fine stuff for their localities and the nation, raising money to fight illnesses, promoting education (especially through scholarships), sprucing up parks and many other good causes. Their decline is of a piece with the general slide of civic life. It’s harder these days to get people to run for office, serve on local boards and join charitable drives.

Cynics like to make fun of such upbeat, boosterish organizations, but they address the need of a healthy democracy to have a wide variety of agile nongovernmental organizations serving the public.

Increased mobility, more dispersed families, shorter-term jobs, the distractions of life on the Internet and the general weakening of the middle class have tended to shrink the memberships of service organizations such as Rotary. Let’s hope that can be reversed. That these clubs generally eschew “virtual’’ meetings online in favor of frequent face-to-face encounters is a particular plus. In-person members often become real friends, and thus more likely to encourage themselves and their fellow members to follow through on good works.

Later, I walked around Bristol, and marveled at its antiquarian beauty.

xxx

The next day I had a meeting on a small (perhaps 32 feet long) sailboat usually moored off Stamford, Conn. We sailed west to off Greenwich, where we anchored near an island with a gazebo on it. It was late in the season, of course, and there were only a couple of other people there. The menacing Manhattan skyline was in the distance.

We went swimming, in remarkably warm water, and talked about a project in China while admiring the beauty of the day – a glory that seems to go on day after day in September and early October in New England. For a few weeks, we have a champagne climate, albeit tinctured with melancholy about what will follow soon enough. But then “the American Season’’ as it has been called, is both a poignant annual ending and an often boisterous beginning.

To the north could be seen the waterfront mansions of the hyper-rich in Greenwich, not that far from slums in Stamford. The “1 percent’’ is what Greenwich is most famous for, and even more so since Wall Street became so much more powerful and rich in the past few decades, via hedge funds, private-equity firms and investment banks. (That the huge California Public Employees’ Retirement System has decided to quit hedge funds might start a wave that could do some damage to a few of the owners of these houses.)

After we had been at anchor for a while, a young woman in our party said that she had to get back to New York pronto. So our skipper decided to sail the dinghy we had been towing all the way to Greenwich, from whose shores the young woman would make her way to the train station. She made the train, but the wind died and so our captain (a film director!) had to row most of the way back to the bigger boat, where we grew slightly anxious waiting.

Finally the wind came up a bit and we saw his red sail, in the sunset. “There’s John!,’’ we shouted, trying to restrain the sound of relief.

Then we slowly made our way back to Stamford through calm and bioluminescent waters; thank God for the inboard motor. I stayed that night in a cheap Stamford motel, some of whose illegal-alien workers might also be leaf blowers on the grounds of the Greenwich estates. There were cigarettes on the motel’s floors and its “breakfast’’ provided only Cremora for coffee. But perhaps that TV’s in the rooms showed very fuzzy images of athletic pornography to channel surfers was adequate recompense for many weary travelers.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com) is a Providence-based writer and editor who oversees this site.