My pre-screen life

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s expected that many more people, what with Zoom, Skype, etc., will be permanently working at home, as employers seek to reduce the danger of infectious disease they might be held responsible for and save a lot of money on real-estate costs.

There are some big drawbacks. Workers will have less idea of what’s going on in their enterprises: they’ll lose some of the ability of understand what their co-workers and bosses are up too; they’ll have fewer opportunities to develop friendships with, and learn from, their co-workers, and they’ll lose the advantages of in-person training.

Body language can speak volumes.

The post-World War II period to about 1990 was the great age of the American office. For much of that time, the economy was healthy, and many folks expected to have long-term work with the same employer.

All the offices I worked in had their social benefits. My first office job, for several summers, was at a shipping company overlooking Boston Harbor and Logan Airport. Much of the work was boring – e.g., filing multi-colored bills of lading – but it had its charms, too, such as talking with truckers at the loading docks, being sent on some errands in downtown Boston, which at that time didn’t look much different than it had in 1937, and going on a lunch boat.

With the newish IBM Selectric typewriters clacking away in the background, I’d chat every hour or so with my office mates, who came from all over Greater Boston and had, for a little office, a remarkably wide range of backgrounds. Most of the men seemed to have served in World War II or the Korean War, and they’d tell me stories about it. The women would often talk about their children, of whom these mostly Irish-and- Italian-Americans, tended to have many, and what was going on in their parishes. But everyone would talk about the news, most of which they’d get from newspapers, which were strewn around the office.

I learned in that office whom to avoid and whom to seek guidance from. One of the latter was an older man, Mr. Gookin, who had had some managerial job at the parent company that didn’t work out and now was a sort of clerk. (Big companies then didn’t fire folks with the abandon they do now.) He took me under his wing. Once, someone, maybe in the cleaning staff, stole $45 I had stuck a drawer. I told Mr. Gookin, who responded: “You’ll lose a lot more than that in this life.’’

Whether in the crowded, smoke-filled and un-air-conditioned newsroom of the old Boston Record America, with its gruff and rumpled scandal-seekers but also with the courtly and natty writer Joe Purcell, who got me the job; the spacious newsroom of the doomed Boston Herald Traveler, which crazies off the streets would sometimes stagger into; the cool and austere newsroom, divided by cubicles, but with many funny people, of The Wall Street Journal, across the street from the doomed World Trade Center; the Art Deco offices of The Providence Journal, and the modernistic but claustrophobic and smoky home of the International Herald Tribune, with its train station-like collection of characters from around the world, there was much to be learned from the people in my office life. Such a range of personalities and backgrounds.

I think that the millions of people who now must work at home will miss a lot of life and learning working at home, though commuting is rarely much fun.

And that was before they cleaned it up

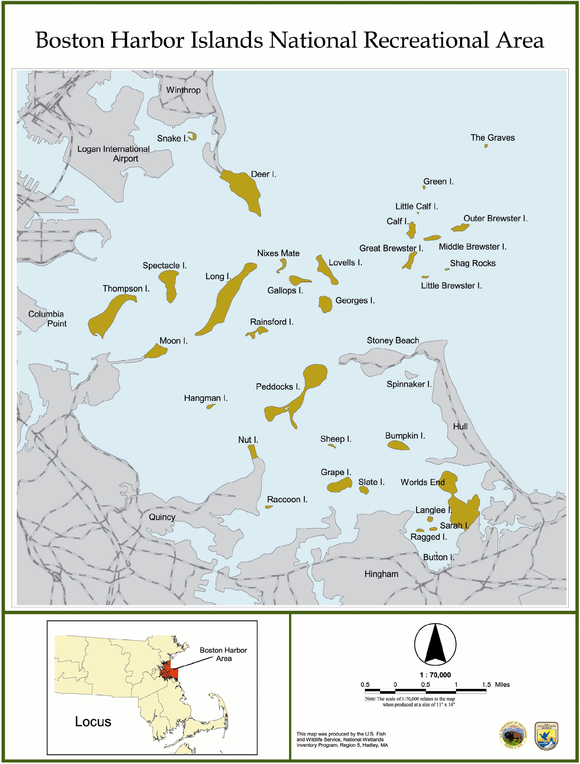

Spectacle island in Boston Harbor. Behind it is Thompson Island.

— Photo by Don Searls

“America, the new world, compares in glamour and romance with the old, and Boston Harbor is one of the most delightful places in America.

— From The Islands of Boston Harbor (1935), by Edward Rowe Snow (1902-82), historian and prolific author.

Edward Rowe Snow memorial plaque on Georges Island, in Boston Harbor

Georges Island is dominated by Fort Warren, built in 1833-61.

Olivia Alperstein: LNG poses grave risks

A member of the Coast Guard escorts an LNG tanker into Boston Harbor in 2016

From OtherWords.org

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is a potential disaster in the making. That’s the conclusion of a new report by Physicians for Social Responsibility, which surveyed an abundance of research on LNG’s threats to public health.

LNG is natural gas that is filtered and supercooled to -260° F, turning it from gas to liquid. That makes it easier to transport in special cryogenic tankers when pipelines aren’t an option, such as for overseas shipping.

But while the fracking that extracts the gas, and the pipelines that often move it, have generated well-deserved controversy, the risks of LNG haven’t gotten as much attention. They deserve more.

The new report finds significant risks from the extraction process (including gas leaks and air pollution), further pollution from the liquefaction process, and serious risks of fires and explosions.

And I mean serious. A full LNG tanker carries the energy equivalent of 55 atomic bombs. If one caught fire or exploded in a populated area, it could make an oil spill look like a picnic.

Even without exploding, the gas poses serious risks to our climate and healt

LNG is primarily composed of methane, a greenhouse gas that is 84–87 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period, which makes it a major contributor to climate change. And the fracking process, the report adds, injects a further “slurry of chemicals” into the surrounding environment. Many are known to contribute to strokes, cancer, and asthma.

LNG export facilities are often located in areas already plagued by dangerous levels of pollution from energy and industrial facilities — often areas with mostly African American, Native American, Hispanic, or low-income families. Facilities may also be sited close to schools and nursing home

“Such proximity, often reflecting these communities’ lack of political power, intensifies the impact on vulnerable populations and people with pre-existing health conditions,” the report notes. These communities are also more likely to lack the resources to address environmental health concerns.

Despite these dangers, there has been a boom in LNG production in the United States over the past 15 years. According to federal regulators, there are over 110 LNG facilities operating in the United States.

The United States is exporting record amounts of LNG to the global market right now, and there are plans to expand LNG facilities in many parts of the country. Meanwhile, the Trump administration is pushing an ill-advised proposal to transport LNG by rail.

Expanding these projects would increase pollution, put human health at risk, and increase the risk of catastrophic fires and explosions. It would also sink billions of dollars into infrastructure that would lock the United States into greenhouse emissions for decades to come.

Thanks to the Trump administration’s systematic rollback of critical health and safety protections, we simply don’t have the safeguards to protect ourselves or our planet from fracking, pipelines, or LNG

As PSR’s new report makes clear, LNG poses a grave risk to our planet, our health, and our future. Instead, we need to demand healthy solutions for our communities. Our health needs to come first — before fossil fuel corporations’ bottom line.

It’s time for decision-makers at all levels to protect their constituents, before it’s too late.

Olivia Alperstein is the media relations manager at Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Flagging Boston Harbor

Kate Driesen on a Boston Harbor boat tour on a relatively warm winter’s day

— Photo by C. Davis Fogg

James P. Freeman: Michael Dukakis: The last traditional progressive

Beaming over the convention of the consonant caucus, the speaker uttered what would be the second most memorable line in the 1988 presidential race: “This election isn’t about ideology, it’s about competence…” This dramatic statement was later bested by George H.W. Bush’s “read my lips…” tax pledge.

Atlanta’s Democratic National Convention that July proved to be, in retrospect, the last stand for Michael S. Dukakis, the last traditional progressive. As progressivism gallops to a new beat of populism, modern-day revivalists should look to Dukakis as their godfather.

He is last major living link to the progressive forefathers. Born in Brookline in 1933, he was also born into the first progressive era of Presidents Roosevelt, Wilson and Roosevelt. It would mark the first time the republic would rely upon government, not self-sufficiency, for sustenance, emblematic of modern times.

Citizens needed progress up from the Founders’ ideas. A strong central government, believing in its boundless abilities, could master public and private affairs, thereby delivering happiness. The Constitution was inelastic; its limitations were to be disdained as impediments to the very progress government sought to engineer. Politics became a science.

Dukakis’s long career in public service is writ large with progressive themes. In 1965, as a young Massachusetts state representative, he introduced a measure to legalize contraceptive use for married couples, an early imprimatur of his activism. For the commonwealth’s conservative Catholic bloc in the House, however, voting on birth- control laws written by Protestants in the 1890s proved to be controversial and complicated. Boston's Cardinal Richard Cushing, remarkably, advised its members in the legislature: “If your constituents want this legislation vote for it. You represent them. You don’t represent the Catholic Church.” The bill passed.

Arguably, this episode — more than John F. Kennedy’s 1960 election to the presidency — helped convert a majority of Catholics from Republicans to Democrats in Massachusetts. Suddenly, it seemed, culture impacted Catholic politics as much as theology. Those majorities remain intact today. Dukakis was elected to the first of three terms starting in 1974 and he remains Massachusetts’s longest-serving governor.

His first attempts as a reformer were rebuffed and he lost the 1978 primary. Not nonplussed, he was reelected in 1982 with an even more robust belief in government’s efficacy.

He originally opposed the initial concept of the Central Artery/Tunnel project in Boston but expanded its scope to accommodate business and government interests. Boston’s Big Dig cost nearly $4 million a day at its peak. Initially a $2.2 billion expenditure in the early 1980s, final estimated outlays are $22 billion, to be paid off in 2038. The administration of this public-private partnership exposed a skewed risk-reward model (socializing losses, privatizing profits).

Under his leadership, after delays and denial for exemption, Massachusetts was found to be in violation of the landmark Clean Water Act. Every day 100,000 pounds of sludge and 500,000 gallons of barely treated wastewater were dumped into Boston Harbor. A federal court, not political epiphany, ensured the cleanup.

Former EPA Administrator Michael Deland said that the commonwealth’s willful disobedience was “the most expensive public policy mistake in the history of New England.” Raw sewage stopped flowing into the nation’s oldest harbor in September 2000.

Dukakis in 2009 reflected on “two of the biggest projects in history at the time.” The harbor restoration — mandated, mind you — “came in on time and 25 percent under budget.” Of theBig Dig, he said: “We all know what happened with the other.”

The difference? “It was about competence of the people running the projects…”

Few remember that Al Gore (not the elder Bush) first raised the weekend-furlough matter during the presidential primary. Dukakis vetoed a bill in 1976 that would have denied murderers, like Willie Horton, such freedom. The program was ultimately abolished after questions were raised about criminal rehabilitation.

Before there was Obamacare and Romneycare there was Dukakiscare. He signed into law the nation’s first universal healthcare insurance program in 1988. A tiny Republican minority quietly disrupted its funding, leaving it an obscure footnote to history.

At 82, still residing in Brookline, still a progressive sanctuary, Dukakis leaves a lasting legacy. He has affected the lives of more residents in Massachusetts than anyone in a century. Clearly, that is a triumph of ideology over competence. As government at all levels struggles with executing competent stewardship, people should look at Dukakis in another light. He at least addressed competence as a core competency.

New-fashioned progressives have abandoned it.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer for the New Boston Post. and a former columnist with The Cape Cod Times.

Celebrating water protection in N.E.

A stretch of the Connecticut River in western Massachusetts.

BOSTON

At a spot overlooking Boston Harbor, once choked with toxic pollution but now home to some of the cleanest urban beaches in the United States, advocates gathered July 1 to thank the Obama administration for closing loopholes in the Clean Water Act that previously left more than half of Massachusetts’s streams at risk of pollution.

“We’ve made so much progress in cleaning up our waterways, and we can’t afford to turn back the clock,” said Ben Hellerstein, state director for Environment Massachusetts. “The EPA’s Clean Water Rule will make a big difference in protecting Boston Harbor, the Charles River and all of the waterways we love.”

The Clean Water Rule, finalized in late May, clarifies federal protections for waterways following confusion over jurisdiction created by Supreme Court decisions in 2001 and 2006. It restores Clean Water Act protections to thousands of miles of streams that feed into waterways that provide drinking water for millions.

“In New England, protecting our water is more important than ever, especially as we work to adapt to climate-change impacts such as sea-level rise and stronger storms,” Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Regional Administrator Curt Spalding said. “Protecting the most vulnerable streams and wetlands — a drinking-water resource for one in three Americans — helps our communities, and this rule provides clarity for businesses and industry without creating new permitting requirements.”

Before the Clean Water Rule became law, small streams, headwaters and certain wetlands were in a perilous legal limbo, allowing polluters and developers to dump into them or destroy them in many cases without a permit. In a four-year period following the rule’s creation, the EPA had to drop more than 1,500 cases against polluters, according to one analysis by The New York Times.

Prior to the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, Massachusetts waterways suffered from decades of pollution and neglect. As late as the 1980s, untreated sewage was regularly dumped into Boston Harbor, and high concentrations of industrial pollutants posed a public-health risk.

The Clean Water Act prompted a major cleanup of the harbor. Today, Boston boasts some of the cleanest urban beaches in the nation, and wildlife habitat has significantly improved, according to Environment Massachusetts.

Advocates pointed out that the Clean Water Act has enabled similar improvements in water quality in many of the state’s most iconic waterways, from the Charles River to the Connecticut River.

Despite broad public support for clean-water protections, polluting industries and some members of Congress are fighting to block implementation of the Clean Water Rule. In recent weeks, congressional committees have approved multiple bills aimed at rolling back the Clean Water Rule.