Times past on Block Island

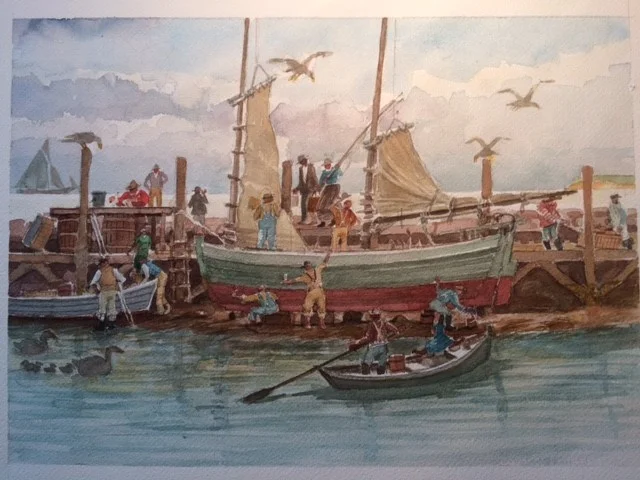

“Gathering Seaweed (watercolor), in the show “Times Past: New Works by William Talmadge Hall,’’ at the Jessie Edwards Gallery, Block Island, through July 2.

He writes: “Seaweed from the beaches on Block Island was gathered as fertilizer and for food. The rule on Block Island in the 1800’s was that access to all beaches was protected for islanders to gather whatever they could find. This included seaweed, fish, salvage from shipwrecks, heating fuel, such as driftwood, and virtually anything else that would help them survive.’’

{Editor’s note: Seaweed aquaculture has been expanding at a good clip in New England in the past few years. Seaweed has many uses and growing it removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.}

The gallery says:

The show “displays the artist’s love of Block Island and history. These works are personal for Hall, a third-generation islander, and encompass a past he hopes that people think about as he immortalizes the rich and fabulous, and now too-often forgotten, history of the island’s people, land and sea in his beautiful watercolors.’’

“Fisherman’s Corner-Old Harbor Block Island’’

Mr. Hall explains:

“Once thick with fishing shacks, the west corner of Old Harbor was the domain of the Block Island fishing fleet. When the steamers on the Fall River Line docked on the east side of this harbor of refuge, the passengers from New York City, Providence, Boston and elsewhere in the region were delivered into a bustling port. But the hurricane of 1938 devastated this fleet; 80 percent of it was destroyed in a few hours. In its heyday, these docks landed enough fresh fish to meet a substantial part of the demands of urban centers in southern New England as well as of the summer resort season.’’

‘‘Victorian Swim Party” (1889)

“During the late Victorian era, which came to be called ‘The Gilded Age,’ Block Island became know as a tourist venue without the social restrictions imposed by, say, Newport high society. Large luxurious hotels offered a more open attitude to anyone, no matter who they were or where their money came from

“The beautiful and romantic scenery and relatively remote location encouraged discreet pleasure and relaxation.

“This painting evokes a slackening of Victorian dress codes and the pure pleasure

of being alive.’’

Islanders using everything they can from the sea

In this watercolor by William Hall, Block Islanders in the 19th Century are collecting fin fish, crabs and lobsters trapped in tidal pools. They also harvested large amounts of seaweed to be used for food and fertilizer. See photos below. This painting is part of an extensive series of watercolors Mr. Hall has done over the past decade of people at work.

He is represented by, among other venues, David Chatowsky Art Gallery, 47 Dodge St., Block Island, R.I. (401) 835-4623

One recipe for “seaweed pudding”:

Put a cup of dried seaweed in a pan and add a liter of whole milk.

Gently bring to boil and simmer for 10 to 15 minutes.

Strain through a fine sieve or a muslin cloth into a bowl and cool.

Put in a refrigerator to set for a couple of hours.

The harvesting of seaweed — mostly kelp — (including increasingly from aquaculture) for food and many other uses has greatly increased in the past few years. And seaweed aquaculture is more and more promoted for environmental reasons. For one thing, it absorbs some of the excess carbon dioxide put into the atmosphere by fossil-fuel burning. For another, seaweed — especially “kelp forests” — is a home for many species.

Collecting seaweed in locally made baskets.

Spreading seaweed as fertilizer on a Block Island farm.

Handing down their boats and their livings

“Wedding Dowry” (watercolor on Arches Paper), by William Talmadge Hall, at David Chatowsky Art Gallery, 47 Dodge St., Block Island, R.I. (401) 835-4623

Hit this link for Mr. Hall’s Web site.

He explains:

“In this picture I show a Block Island Double-Ender fishing boat being brought up on the beach at the end of a day around 1840, with the help of oxen and block and tackle. The boats, a mainstay of the island’s fishing and transportation in the 18th and 19th centuries, were built by islanders to circumvent the problem of not having particularly safe harbors, necessitating that boats be drawn up into the dunes at night to wait for a favorable tide and reasonable weather.

This required the islanders to help each other daily, building a tight communal bond.

Fishing from the family-owned boats was so successful in harvesting the plentiful fish stocks around the island that the Block Island Double-Ender fleet grew large and the boats become famous for seaworthiness.

In this picture, the newlyweds on the boat to the right prepare to forge ahead in their new boat. Two generations of Block Islanders watch this ceremony as they sit on the beach at day’s end in front of a small fire.

Over the years, fathers handed down their boats to sons, and if there were no sons then a boat might be a dowry gift to a daughter and son-in-law.

The new husband brought the potential of a bigger extended fishing family once he had proven himself a worthy fisherman and become the the ascending key figure in the future.

Either way, the prize was the boat and the legacy it represented to a self-sufficient fishing community bolstered by shared beliefs.

xxx

I’m a 74-year-old artist. My family has been a part of Block Island's history for five generations. My father was the first male Hall on the island not to pursue fishing as a career, although he harpooned swordfish until he was drafted into the Army, in World War II.

I’m a watcher, and many of my paintings are about people working — the simple grace of people doing what they do each day to make a living. These folks don’t dwell much on the meaning or the ultimate results of what they do. They go with the flow of a continuum of work.

William T. Hall: An island’s crucial boat and the widow’s fish

On the beach with a Block Island Double Ender

— Watercolor by William T. Hall

Block Island is a small landmass shaped like a pork chop 16 miles off southern Rhode Island. It’s where my father was born, in 1925. His entire family were fisherfolk. He got his start fishing at age 10.

Historically, the old salts depicted in the marine art and stories of the past were men, but the wives, mothers and daughters of island fishermen were essential to the life of any Block Island family that made its livelihood from the sea.

Of course, as usual, women saw to all the usual unsung details of daily life in the home and spiritual life in the community, but little remembered today is the extent of the decisions made, and physical labor provided by island women, and how important that was to their family’s survival and success.

Long before my father was born, the indigenous tribes and white settlers on the island took to the sea for their livelihood. They first had to overcome the major geological disadvantages of the island. The high bluffs and open ocean exposure on the southeast corner of the island were perilous, and to the north at North Light were the shallows off Sandy Point that still claim lives of surf fishermen today. These were daunting and dangerous obstacles. For many years the shores of Block Island challenged captains with hazardous approaches and no reliable anchorages.

Progress through adversity

Consider the challenge of designing boats to use at Block Island. For many years, the “perfect Block Island boat’’ was dreamed about, prayed about and then modeled out of wood. It occurred to the early settlers that the way to create a seaworthy vessel on a beach had already been invented by the Celts and Vikings . With a foggy notion of history and woodworking skills barely sufficient to fabricate a house, the new islanders patched together their own unique surf-wise boat. The design was not beautiful, but it was practical because it was based on two important borrowed principles from sea-faring people many hundreds of years before.

It should be sturdy, with two sharp ends for launching from beaches and surviving a following sea when landing. It should have a sail arrangement

best described as “simple and flexible.” It allowed for two small sails, which when reefed down, looked like oversized canvas handkerchiefs. These design considerations proved essential to moving the boats around rocks, then from high cresting waves down onto safe sandy beaches.

The most important aspect of this design was that the boats could be launched into the surf and retrieved from the brine by a small group of men and, yes, women, often with the help of oxen, horses, mules and mechanical hauling contraptions called “capstans”.

This homely workboat was a dory called “The Block Island Double Ender”. It could be launched from the beach into the morning surf and then brought back at night through a different tide, to be stored high up in the dunes safe from northerly storms. This kind of boat varied from 22 to over 36 feet long and was weighted by fieldstones for ballast that would be thrown overboard to balance the weight of a daily catch. The boat was destined to become the mainstay workboat for the island from before the American Revolution but eventually, of course, was made obsolete by steam and gasoline engines.

The stories of the colorful fishermen who manned these seaworthy boats earned them a certain notoriety with many world-class sailors. The boats form a deep mythology as colorful as the exploits of the gods on Mt. Olympus. They had names such as Dauntless, Island Bell and Bessie, I, II and III. There were perhaps as many as 50 boats built and launched from coves around the island. One such beach is even named “Dories Cove”.

For over 200 years, they faced Neptune’s furry and a vengeful Old Testament God, as they fished a bountiful sea around Block Island. Then, over just a few decades, the boats melted away. The end of these boats was ignoble. Finally abandoned by the careless hands of progress, their exposed ribs and rigging melted into the island’s underbrush and rose-hip bushes. It was said by a Civil War veteran, “Only those who had witnessed soldiers left unburied after a battle can feel the shame at the sight of this wasteful demise”.

The holiest of testaments paid to Block Island Double Enders was repeated by the captains who had fished in them, “With all that time and everything they went through, only one boat was ever lost to the sea”. Is it true? As an owner of an original reproduction of this wonderful boat I can only say, “It is possible”.

All along, women have played a part in the history of the island, its boats and its success as an island community. In the early history, when a man’s hand heaved at the side rails, or the harnesses of the

oxen, female voices as well as men’s voices were heard shouting as they all pulled in unison with the men. Every able-bodied fisherman, woman, boy and elder was needed to launch and retrieve the boats of the fleet each day.

Women also helped with maintenance, sail repair, outfitting, marshaling supplies, cleaning the catches, gathering and managing bait, all while feeding their families and sharing child-care.

Some women were on the beaches for much of the day waiting for the boats to return. And some women might ride the family mule back to work in their gardens, feed livestock and hang laundry while they kept an eye on the horizon for their family boat to come into sight. Some made stews and chowders and roasted potatoes in the coals of beach fires while they waited. Some cared for the oxen and set wire minnow traps in the salt estuaries. Some dug quahogs for bait from the wet sand on the lower parts of the beaches for the next day’s bottom fishing. \

When the boats were out the women were assisted by old men and school-age boys and girls, before and after school. Young girls helped the working mothers by babysitting the youngest children, tending stew pots, mending nets and making clothing. The women’s contribution would be universally appreciated on Block Island and earn them an equal place in the fabric and soul of the island.

At the time when my father was young many things had changed. Commercial fishing had become totally the purview of men, often symbolized artistically by heroic images of stalwart captains on mammoth commercial fishing boats. By this time, most daughters of fishing families were educated and provided such services on the island as teaching, nursing, real estate, bookkeeping, town business, cab driving and tourism, to mention only a few.

Regardless of these changes, appreciation of women’s role on the island continued. Quiet acknowledgement by giving shares to those who contribute became a tradition in my father’s generation called simply “The Widow’s Fish”.

Although difficult to translate directly, it means always making sure that all the elder and/or widowed women still living on the island would receive fish from every day’s catch. It was standard for every fisherman and farmer on the island to share part with those in need with little fanfare. Sermons in the island’s churches, grace said at daily meals, dedications at public benedictions and remembrances of departed fishing folks were often framed around the notion of “sharing and appreciation,’’ including the crucial role that women played.

I remember this quiet homage paid by my father during our summer vacations, from Vermont, on the island. Although he had migrated off the island to work as a salesman and gentleman farmer, we vacationed on the island, visiting relatives and friends and fishing daily on boats owned by relatives.

One day we had caught more flounder than we could eat, and my father made sure to separate out the catch into portions or “shares”. In that bounty was a special offering, something he called, “The Widow’s Fish”. He always put that portion aside during the filleting. All the harbor’s fishermen had one or two additional people outside their immediate families who were living alone and as Father would say “are living a little closer to the bone than we are”.

In those days, he’d leave the boat and go up the dock to the phone booth by Ernie’s Restaurant. There he’d call a prospective list of names to ask if they could use some flounder, bluefish, fluke, black bass and occasionally

Swordfish. (The last were getting scarce in those days.) I remember the names on his list -- Ida, Annie Pickles, Aunt Annie Anderson, Blanche Hall and Bea Conley. These were elderly ladies whose homes we often visited on the way home with pails of filleted fish.

As I later found out, my father, when he was a teenager, had often crewed as a deck hand or swordfish striker for the husbands of the ladies we visited. All or most of the men were captains who operated fishing boats that Dad had worked on before he went into the Army, in 1944. It wasn’t until later in life I found out there was an added depth to my father’s gratitude.

In those old days these women had found a way to stretch many of their own family meals so that my father, orphaned at age seven, could stay for dinner.

These grateful ladies of the island formed a matriarchal umbrella of love and service to each other and their community. They always remembered my grandmother Suzie Milliken, whom some fondly called “Sister Suzie,” through a custom they referred to as “calling her to the room’’. The expression was used from Victorian times to mean connecting with a departed soul in a séance. As they thanked and hugged my father, they tearfully called him by the boyhood nickname Suzie had given him.

“Billy,’’ they assured him, “Suzie, would be proud of you for remembering to bring us our fair share”.

William T. Hall is a painter, writer and former advertising agency creative director based in Florida and Rhode Island.

Fishermen at the long-gone fish market co-op building at Old Harbor, Block Island, in the ‘40s.

— Photo courtesy of George Mott

Todd McLeish: Seeking strategies for sustaining bay scallops

Bay scallop staring at you with its blue eyes

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

In the Great Salt Pond on Block Island, native bay scallops are thriving like nowhere else in Rhode Island. Scientists from The Nature Conservancy survey the 673-acre tidal harbor every autumn and have recorded hundreds of scallops each year, despite as many as 50 recreational shellfishermen harvesting scallops from the pond each November and December.

The same cannot be said of the rest of the Ocean State’s waters, however, where bay scallops are few and far between.

On Block Island, Diandra Verbeyst leads a three-person team of Nature Conservancy scuba divers and snorkelers who monitor 12 sites around the Great Salt Pond. They have counted an average of 225 scallops annually since 2016, up from just 44 observed by previous observers in 2007, the first year of monitoring.

“There are slight rises and falls from year to year, but the population is pretty stable,” Verbeyst said. “Based on the 12 sites we monitor, the population is indicating that there is spawning happening each year, and there is recruitment to the population.”

In addition to scallop data, Verbeyst and her team also collect information on water quality and other environmental conditions during their surveys.

“The scallops are an indication that the ecosystem is healthy and doing well, and for me, that’s fascinating in itself,” she said. “No matter where you are in the pond, there’s a good chance you’ll see a scallop.”

Bay scallops are bivalve mollusks with 30-40 bright blue eyes that live in shallow bays and estuaries up and down the East Coast, preferring habitats where eelgrass is abundant. They are short-lived animals — most don’t live more than two years — and are significantly smaller than sea scallops, which are found farther offshore and are harvested by the millions by New Bedford-based fishermen.

Chris Littlefield, a Nature Conservancy coastal projects director and former part-time shellfisherman on Block Island, recalled collecting scallops as a child in the Great Salt Pond 50 years ago, and he has been gathering them in small numbers for his family’s consumption ever since. He said the scallop population received a boost in 2010, when immature scallops grown at the Milford {Conn.} Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were dispersed into the pond in a project funded by the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

“That project broke through some kind of threshold,” Littlefield said. “Scallops weren’t as abundant before that, and they used to be confined to certain key locations and that was it. But now they’re more abundant and more people are finding them and harvesting them.”

Unlike Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and a few locations on Cape Cod and Long Island, where regular seeding of immature bay scallops has resulted in thriving commercial fisheries, Rhode Island has a tiny commercial fishery for bay scallops — fewer than three fishermen participate — and the fishery is not sustainable.

Anna Gerber-Williams, principal marine biologist for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division of Marine Fisheries, just completed the first year of a three-year effort to assess the state’s bay scallop population. She is focused primarily on the salt ponds in South County, especially Point Judith Pond and Ninigret Pond, which historically had healthy bay scallop populations.

“We manage and regulate the bay scallop harvest, but besides Block Island, we haven’t had an actual assessment of what the population looks like in Rhode Island,” Gerber-Williams said. “We know it’s pretty low, and we know the actual commercial harvest numbers are very low. But we don’t have anything to base our management on. The hope is that this project can turn into more long-term monitoring, similar to what’s done on Block Island, and maybe lead to restoration efforts.”

Based on her first year of surveys, Gerber-Williams said there are self-sustaining populations of bay scallops in Point Judith Pond, and their abundance can fluctuate significantly from year to year.

“Scallops are very habitat-dependent,” she said. “The habitat in the salt ponds is very patchy, and those patches are very small.”

Unlike clams, which bury themselves in the sand, bay scallops sit on the seafloor and can swim around by rapidly opening and closing their shell, making them difficult to track and count. Gerber-Williams said they are threatened by several varieties of crabs, which can easily crush the scallops’ shells with their claws.

“Part of the scallop’s strategy is to hide from the crabs in the eelgrass,” she said. “When they’re younger, they attach themselves to eelgrass blades to keep themselves above the bottom and out of reach of predators.”

Dan Torre at Aquidneck Island Oyster Co. experimented this year with growing bay scallops in cages in the Sakonnet River off Portsmouth. He bought scallop seed from area hatcheries last July, and they are approaching marketable size now. He has contracted with one local restaurant to buy his experimental crop, with hopes of scaling up the operation next year.

“I believe there’s a market, but it’s a niche market,” he said. “Normally with sea scallops, you sell just the shelled adductor muscle, but with bay scallops you sell the whole animal. The shelf life isn’t the longest, but it seems like there are a bunch of restaurants that are eager to try them.”

In an effort to figure out how best to restore wild bay scallop populations in the region, the Rhode Island Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation is collaborating with The Nature Conservancy to synthesize what is known about the history of the bay scallop population and fishery in Point Judith Pond.

According to Dave Bethoney, the foundation’s executive director, it will be combined with information about scallop fisheries in Massachusetts and Long Island, N.Y., as a first step to developing a restoration plan.

“How to make them sustainable is the real puzzle,” Bethoney said. “Even successful efforts on Long Island are based on a seeding plan — getting scallops every year from aquaculture facilities to replenish them. They have successful populations, but they’re not self-sustaining. I don’t know how we change that.”

Gerber-Williams agreed.

“In my opinion, the way to boost populations here and keep them at a level that’s sustainable for a good fishery in Rhode Island, we would have to have a seeding program similar to what they have in Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard,” she said. “Every year they put out thousands of baby bay scallops. They seed their salt ponds every single year to keep a decent fishery going.

“So the next step for us would be to do that kind of seeding program in Rhode Island. We’re in the process of creating a restoration plan for various species of shellfish in Rhode Island, and my hope is that bay scallops are a part of that.”

Hopefully the current researchers go back to the North Cape shellfish injury restoration project, which included release of bay scallop seed into the South County salt ponds, to learn about what worked or did not work for the multi-year that wrapped up by 2010. The reports are available and some of us who worked on the project are available to discuss challenges and successes.

Todd McLeish is an ecoRI News contributor.

Eelgrass is prime habitat for bay scallops.

Great Salt Pond battle goes on

Block Island, with the Great Salt Pond the body of water with many boats in the top middle.

— Photo by Timothy J. Quill

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

One look at an aerial photo of Block Island’s Champlin’s Marina, on ecologically fragile Great Salt Pond, shows that it’s already too big. And now, through a highly dubious mediated settlement that’s an (illegal?) end run around an earlier denial of the project, the business could build 170 feet further into the pond (which serves as a harbor). Champlin’s campaign to take over more of the Great Salt Pond sometimes seems to have gone on for centuries but it’s only been since 2003!

While affluent folks from the region might love having more places to tie up on the island, adding more boats would inevitably increase pollution in the Great Salt Pond.

Retired Rhode Island Supreme Court Chief Justice FrankWilliams brokered this deal in secret negotiations involving the state Coastal Resources Management Council and Champlin’s. State Atty. Gen. Peter Neronha is rightly looking into this suspicious agreement.

Economy looking wetter in Rhode Island

The tiny, five-turbine wind farm off Block Island. It’s still the only offshore wind farm in the U.S. even as there are huge offshore wind farms in Europe.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s always good to see the Ocean State taking more advantage of, well, the ocean. There are two developments worthy of note. One is Gov. Gina Raimondo’s plan, working with National Grid, for Rhode Island to get 600 more megawatts of offshore wind power, as part of her hope to get all of Rhode Island’s electricity from renewable sources by 2030. That’s probably unrealistic but a worthy goal nonetheless. Certainly it would be a boon for the state’s economy to have that regionally generated power. Ultimately, with the development of new advanced batteries to store electricity, it would lower our power costs while making our electricity more reliable, helping to clean the air, slowing global warming and providing many well-paying jobs.

There is, however, the danger that if the Trump regime stays in power, it will slow or even sabotage offshore-wind development because it’s in bed with the fossil-fuel sector.

Then there’s the happy news that the Rhode Island Commerce Corporation plans to buy more land for the Port of Providence. This would come from a $70 million port-improvement bond issue that voters approved in 2016. $20 million of that is for expanding the Port of Providence. Considering its geography and location, Rhode Island for more than a century has used far too little of its potential to host major ports, with of course Providence and Quonset being the main sites.

Observers see considerable synergies between those ports and big offshore-wind operations off southeastern New England, much of which could be served from Rhode Island, as well as from New Bedford.

Please hit these links to learn more:

https://www.utilitydive.com/news/national-grid-to-develop-600-mw-offshore-wind-rfp-for-rhode-island/587866/

https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rhode-island/articles/2020-10-27/after-4-years-state-moves-to-buy-land-near-providence-port

William T. Hall: On his island, one last time for my father

While watching the recent movie Midway, about the Battle of Midway and the tragedy of Pearl Harbor, I heard a sad familiar sound that reminded me of my father’s funeral. It was the sharp report of seven rifles being discharged all at once. It is unforgettable.

“BLAM”!

Then a slight pause...

Then again...

“BLAM”!

Then one last time...

“BLAM”!

Must we punctuate tragic moments with such a horrid sound?

The answer is...

Yes we must.

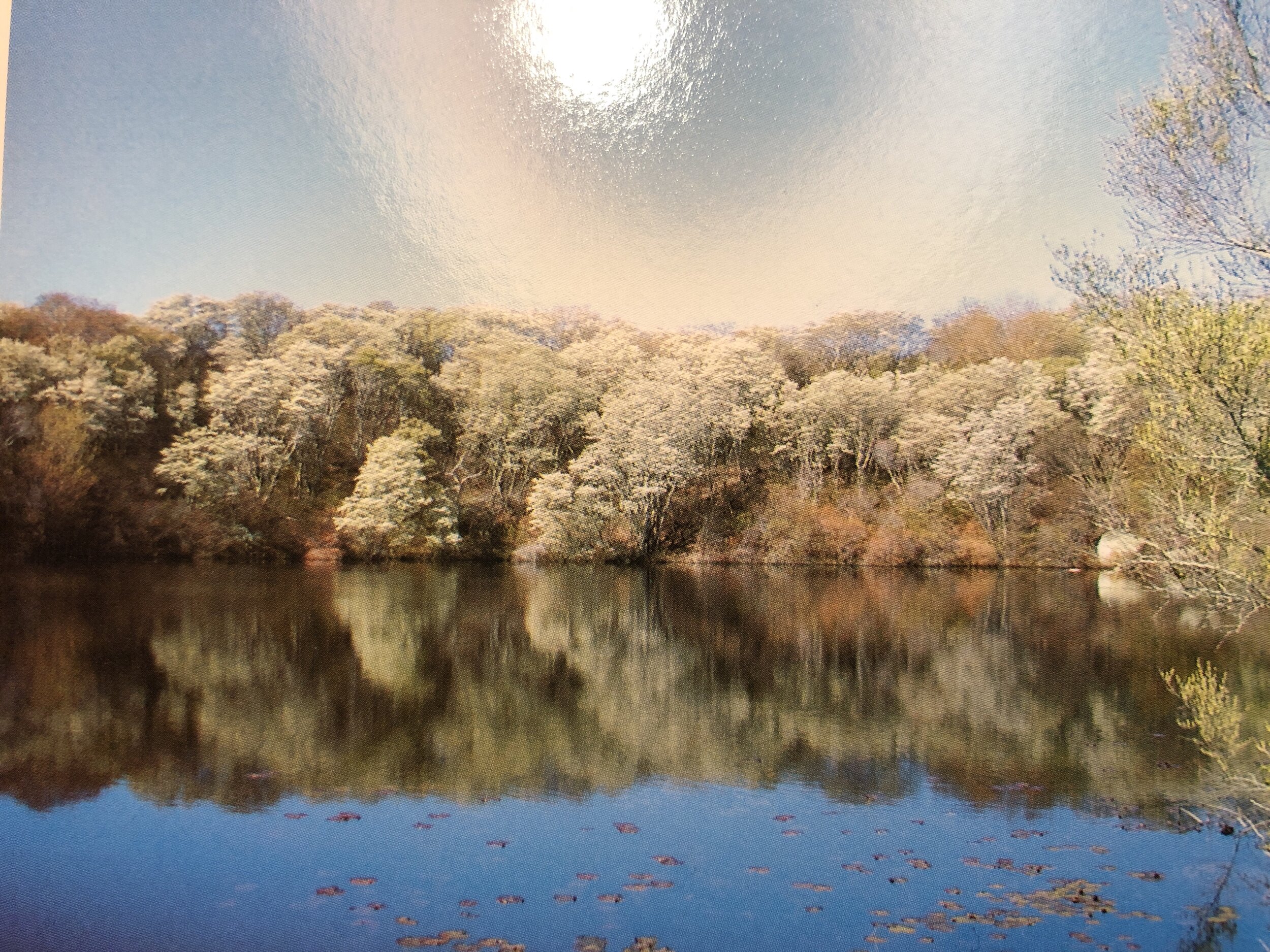

The shad in bloom

— Photo by Kevin Weaver

Preparations for a Memorial

My mother and I carefully picked a day in early May 2000 to inter my father, William Hall, in the cemetery on his ancestral home, Block Island. It was our best guess when the shad tree bloom would be in full array.

Until his last breath, at age 74, he had asserted that he’d not missed being on the island for “The Shad” since World War II.

It’s a spectacle of nature. It’s a moment in a living dream when large parts of the island look like swirls of white butterflies. It creates a cirrus-cloud wisp of magic and myth. Throw in some Hollywood-style ecclesiastical lighting and you’ve got the picture of my father’s romance with “The Shad”.

It was no matter to him that this heavenly show for the rest of the year could be easily described as just woods.

What Everyone Knows

A normal burial on Block Island is handled as a package deal.

The grieving party whose just-deceased relative (or friend) is “from away’’ agrees to a final price covering shipping the loved one in a hearse to the island on the ferry boat. The price includes the homey funeral service at the Harbor Baptist Church, the short procession to the burial site and the post-burial “coffee-klatch” back at the church.

Then after a few hours - and in the middle of hugging relatives and meeting new spouses of forgotten cousins -- starts the panicked reality of the late hour, and the dash to make the last boat back to the mainland. Luckily, the ferry docks are within sight of the church and the captains tend to wait for every last grieving straggler.

To avoid anonymity in death those Block Islanders who have drifted off the island need to be reintroduced to it so that they can be remembered before being forgotten up in the cemetery. Even the descendants of the original English settlers, named prominently on Settlers Rock, have to go through a process of re-emergence during a well-choreographed day-of-burial. It’s like reestablishing their original footprints in the snow after they have long been obliterated by a lifetime of snowstorms. To achieve island quasi-immorality it only takes this one day, with its own special down-homeyness.

Someone Special

So went my father’s last trip back to Block Island, there to be quietly eulogized as one of those island kids who for one reason or another fell into “Off-Islander“ status somewhere along the line.

Human time can be defined in waves. In my father’s case he would be counted among the World War II veterans, Pacific Theater, brand of survivors. At the funeral he would be praised for being a successful businessman, a good husband and a good father, but none of his fishermen relatives or old island cronies would be left to nostalgically tell mourners stories about “that kid” known as a star harpooner of swordfish.

My father had started commercial fishing in 1936, at 10 years old. That’s when he got permission from his father, Allen Hall, to climb the mast and sit on the cross tree of the Edrie L. From that perch, 24 feet above the deck, he was to try his hand at spotting swordfish on his Uncle Charlie’s boat. He excelled because of his excellent eyesight and precise directions given to the helm to find the fish. Soon he was recognized for his accuracy with a harpoon.

By 14 he was the youngest “boy” harpooning swordfish in the fleet and was earning a full share of any fish he spotted or harpooned. This minor local notoriety ended when he was drafted into the Army and shipped out to the Pacific.

That war took many islanders away from Block Island, some to pay the ultimate price of liberty and some to find their way to a more expansive future than could be hoped for on the island, where few returned to live. My father’s war experience did not scar him and he lived a fruitful life, including raising a family and prospering in another part of New England far away from the coast. Although he visited his island family often over the decades his relationship with the place became increasingly remote - and more that of a tourist.

The reality was that the family was thinning out. This hit him hard during the funeral of the oldest Hall elder on the island and it gave him a feeling of a fading heritage. Now more strangers were waiting on the dock meeting the ferry boats when not so long before there had been a receiving line of loving relatives and friends, each shaking his hand, hugging him and calling him by his childhood nickname, “Billy”.\

The island’s identity was shifting. My father was a realist and his life was changing with the times, which he accepted as inevitable. He just didn’t welcome the change with a joyful heart.

This was the man in the shiny hearse rolling off the ferry to return to the island he loved so much. He’d soon be back with his family and relatives for good.

A Good Life

At the funeral service we confirmed through loving remembrances that my father’s life had been by all accounts a good one. The funny tales softened the sorrow.

Everyone at the Harbor Church service agreed that we had all been blessed by his 74 years with us. Meanwhile, as we eulogized him, it became evident that something big was happening outside. There was something at the edge of our senses that suggested that there was a chance that this simple memorial for my father might turn into “A Perfect Block Island Funeral”. It might enter a world where bad was good.]

The first sharp clap of thunder boomed even before we saw the lightning. We realized that what we had sensed had been rolling thunder for some time. The stained-glass windows, organ music, prayers, songs and laughter had masked the storm that was now creeping up on us from the southeast side of the island.

The room was getting darker but it was 11 in the morning. As the wind whipped at a tin gutter somewhere on the roof, the pastor’s wife quietly tiptoed around the room clicking on a few floor lamps and wall lights. People watching her nudged each other quietly. Looking around the room we saw that the local mourners (from the island) were dressed in rain gear. They had rain hats stuffed in their pockets and waterproof footwear ready under their seats; one even had unbuckled galoshes on over his shoes.

In contrast, the mourners “from away” (non-islanders) looked unprepared in their comfortable spring sweaters and dresses. Luckily, they at least had designer-styled trench coats on the hooks in the coatroom. But rain hats, boots and umbrellas for a muddy gravesite ceremony were not evident anywhere in this crowd.

The second thunder clap brought everyone to attention and a slight whimper was heard. Flinching erupted in attendees with over-active startle reflexes. Those who seemed prepared for bad weather were rolling their eyes with wonder as if asking, “Don’t these people from away listen to their local weather reports”?

The weather had changed from undecided to absolutely bad. The modest stained-glass windows rattled with wind gusts and pelting rain. The warm sidelights that the pastor’s wife had switched on were soon augmented with the big overhead lights. Everyone was getting the message that it was going to be stormy at the gravesite.

The Road to Valhalla

No one is more aware of the changes in the island’s social make-up than those who consider themselves “Real Block Islanders”.

“Real” was defined generations ago as “born on Block Island” and of course eventually buried on Block Island. That was the perfect life’s arch of a true islander. Very few can claim that distinction any more.

Evolving medicine and more reliable ferry service have nullified the “island-born” stipulation. In 1926 my father was born in Newport and the next day started his life on Block Island as a “Real Block Islander”. In spite of being hospital-born he met the requirements then needed to be “Real”.

He was born prematurely and had to be kept warm for his first four weeks wrapped in moist towels perched on the edge of an open oven door. My grandmother’s kitchen became Block Island’s first premie ward. My father was attended by every mid-wife and aunt on the island and he soon became everyone’s community property. Thus began his neventful life.

By when I was born, in 1948 ( sadly not on the island), things had changed. It had become a tourist spot. A popular promotional motto was being targeted at people discovering Block Island for the first time. It went like this: “Block Island, come for the day and stay a lifetime.’’ The enthusiasm of first-time visitors on seeing the island’s beauty began to create a new social structure on the island. The newcomers, some of whom became summer residents, brought new ideas, new talents and new personal objectives, but no matter how extraordinary their efforts, they could not line up in that parade of Original, True and Real Islanders. They would never be on that path to immortality and obscurity that leads eventually to Block Island’s cemetery.

In spite of the obstacles to membership in this coveted club of Real Islanders those with the strongest desire for acceptance are still drawn to try to break into the line.

Any deceased islander with an army of mourners headed for the Harbor Church can cause quite a stir, especially when the forecast is for stormy weather and high seas.

When the shiny black hearse carrying my father’s remains crossed the gangplank onto island ground, the island’s grapevine heated up, leading to calls to the church for information.=

Meanwhile, the appearance of a large group of mourners not properly attired for the coming deluge meant that the person about to be buried was probably an “Off Islander,” but scuttlebutt had it that there would also be a rather large island contingent at all or part of the proceedings.

Source Number One

Besides the church, there were other sources of solid information.

Block Island cabdrivers meet every ferry from May 1 to the end of the following November. Only well-established islanders can obtain one of those coveted cab licenses, the possession of which is a channel for a wealth of information about what’s happening on the island. The parking area for the cabs is within plain view of the ferry landing. If you know one of these cabbies you can get first-hand, inside information about what is unfolding at the dock, as well as stuff from any dark corner of the island and the usual sketchy and juicy daily gossip.

I surmise that an inquiry from an island newbie to a cab driver about my father’s hearse might have resulted in a conversation like this:

“Hi, Ed, How you doin?’’

“Good.’

“Hey, who’s that they’re rolling off the boat in the hearse?’’

“Oh Yah, that’s Billy Hall. Yep. He grew to the Sou-East. In the house where Jacobs live now. ‘’

“Lots of well-wishers, eh? I guess he must’a been well known?’’

“Oh, Yah. Billy was a good man. Good family - all fishermen. His mother was a Milliken. Yep, we’re – cousins, I think?’’

“Whad he do for a livin?’’

“Not sure – he moved way af-ta th’war. (pause), but when he was young he could really stick a swordfish. Yessiree. Few better.”

“Oh...?’’ (so on and so on )

And at the Airport

Traditionally, additional information could be obtained at the Block Island Airport lunch counter. It was where the cabbies sipped coffee all day between fares and mingled with passengers waiting for their flights.

On days of big funerals, cabbies, counter girls and mourners from the island and off it exchanged hugs, jokes and news. It was a clearinghouse for information and gossip -- and pie. Everyone seemed related and soon you suddenly felt related to them also.

If newbies liked what they had heard about the deceased in the hub-bub at the lunch counter it would not be unreasonable for them to attend the funeral and go to the gravesite to see whom they might know there. In this way even a newbie might develop a fast, if remote, link with the mourners.

One point was understood. Newbies had to stay for the entire event, no matter how bad the weather. If you invested in saying goodbye to an old Block Islander you were in it for the full course, probably including the coffee-klatch after the burial. This could be important social collateral years later if the deceased name’s came up in conversation. If you had shown up to pay your respects, you could say:

“Yes. I know I was there!”

It was like attending a Viking funeral so you’d know the way to Valhalla.

When Bad Is Good

The wind blew hard and the pouring rain came at the mourners horizontally and from three directions at the gravesite. The lightning, thunder and rain were relentless. The oldest ladies sat in folding chairs under wet tarps and plastic drop cloths with grandchildren squeezed in between them.

Things flew away never to be recovered, but no one left and the ceremony was not rushed. The general mood was sad, but with mourners’ sense of satisfaction that they were joining in a celebration of a life well lived. The hundreds of flags on the veterans’ graves all around snapped in the “Moments of Silence” requested by the pastor.

At the time of my father’s funeral many veterans were being laid to rest every day of the week all over America. Due to the large number of burials, it was nearly impossible to get an honor guard or an official bugler to attend individual funerals. I could not emotionally accept this situation but nor would I complain. My father would not have complained.

On Block Island we have one rule, “We take care of our own”.

Our cemetery is neutral ground, outside of the bounds of daily disputes. This hallowed ground is where we commune with the past and honor individuals whom we respect dearly no matter how long away -- or how recently arrived.

We made an arrangement to honor my father in a way he’d have enjoyed. In a gesture of respect to our family and to the many other veterans whose flags flapped together with his in the wind, a dear family friend and well known federal official provided us with the most memorable final note that my mother and I could have hoped for.

He was to be my father’s one-man honor guard.

Observing the usual safety measures, the honor guard loaded a blank shell into my father’s 12-gauge shotgun, left the mourners at the gravesite and walked slowly and ceremoniously to the top of a small rise.

We could see his hat fluttering and his coat whipping in the wind. His silhouette against the dark sky evoked heroism and the shad bloom around us. As he mounted the shotgun’s stock firmly to his shoulder we could see that his shooting glasses were being pelted by the rain. Time stood still for just a moment. We waited for the sound that gun would make -- one last time.

Blam!

The wind and the rain muffled the report.

White smoke hung in the air above the shooter, and then disappeared downwind into the white cloud of shad trees in the distance=

At my side my mother, inside father’s old raincoat, whispered:

“Perfect.”

William T. Hall is a painter, illustrator and writer based in New England, Florida and Michigan.

Expand the charm north in Newport

Of course not every neighborhood in Newport can look like this 18th Century section of “The City by the Sea.’’

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Newport is a fascinating little city, with its dramatic coastline, history, architecture and thick demographic/ethnic stew. And now there’s an interesting battle underway over how to redevelop its North End, a neighborhood with lots of low-income poor people and rather ugly cityscape. Visually, it sometimes seems that there’s “no real there there,’’ as Gertrude Stein said famously about Oakland, Calif.

I just hope that the final plan doesn’t result in making it look like a suburban-style shopping center/ office park with much of the space taken up by windswept parking lots. To show that it’s part of a city much of which is famous for its beauty, it should look like part of a city, with the density of one, and with green parks as well as a mix of new housing – resident-owned and rental -- stores and restaurants (with space for outdoor service) whose design speaks to the most attractive aesthetic traditions of the area. Newport is well known for its extremes of wealth and poverty. Thoughtful redevelopment of the North End can at least attempt to provide the unrich there with the opportunity to live in a neighborhood with the sort of built beauty than improves their socio-economic, as well as psychological, health, including by drawing in some of the visitors, and their wallets, who previously only went to the famous historic areas in the southern part of the city.

Village center on Block Island

I spent a day and night on Block Island last week: Gray skies, gray water, gray buildings and lots of red pants.

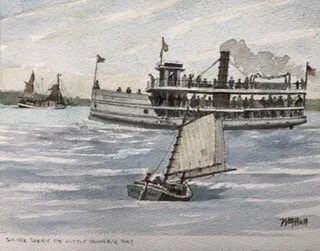

Hard-working ferries, especially in summer

The Island Belle ferry at Old Harbor, Block Island, around 1900. Watercolor by William Hall.

Note from Mr. Hall:

I am an artist and part-time Rhode Islander who spends much of each summer in Harbor Springs, Mich., on Little Traverse Bay. This was a busy logging area in the mid 1800’s to 1935 and has also been for many years a summer place, especially for affluent people from the Midwest.

There were a total of about a dozen ferries, mostly from 58 to 96 feet long, linking several Lake Michigan communities between Petoskey and Harbor Springs between 1875 and 1930. These were steam-powered and ran a vigorous schedule, stopping every 15 minutes at docks. See one of those ferries below, and information about a Harbor Springs show of my ferry watercolors by hitting this link.

Block Island (where some of my family lived), Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket also owe much of their development, and today’s daily bread, to such glorious little workhorses. I have painted many pictures of boats on the southern New England coast over the years. It’s fun to create images of vessels on fresh water, too.

For original art, prints, posters, drawings, information and stories, visit williamtalmadgehall.com.

Tim Faulkner: Future of offshore wind hangs on agency's report

Progression of expected wind turbine evolution to deeper water

From ecoRI News

The forthcoming report from the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) on the cumulative environmental impacts of the Vineyard Wind project will determine the future of offshore wind development.

BOEM’s decision isn’t just the remaining hurdle for the 800-megawatt project, but also the gateway for 6 gigawatts of offshore wind facilities planned between the Gulf of Maine and Virginia. Another 19 gigawatts of Rhode Island offshore wind-energy goals are expected to bring about more projects and tens of billions of dollars in local manufacturing and port development.

Some wind-energy advocates have criticized BOEM’s 11th-hour call for the supplemental analysis as politically motivated and excessive.

Safe boat navigation and loss of fishing grounds are the main concerns among commercial fishermen, who have been the most vocal opponents of the 84-turbine Vineyard Wind project and other planned wind facilities off the coast of southern New England.

Last month, Rhode Island state Sen. Susan Sosnowski, D-New Shoreham and South Kingstown, gave assurances that the Coast Guard will not be deterred from conducting search and rescue efforts around offshore wind facilities, as some fishermen have feared.

“The Coast Guard’s response will be a great relief to Rhode Island’s commercial fishermen,” Sosnowski is quoted in a recent story in The Independent. “We have many concerns regarding navigational safety near wind farms, and that was the biggest.”

The anticipated release of the BOEM report coincides with President Trump’s efforts to weaken environmental impact reviews for all energy proposals, including wind, coal, and natural gas. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reviews have slowed pipeline projects such as Keystone XL and, as of last summer, Vineyard Wind. Both industries praised the move to loosen environmental rules. Environmentalists, meanwhile, fear that the removal of terms such as “cumulative,” "direct," and "indirect" from NEPA’s directives will nullify future federal efforts to address the climate crisis.

Once the expanded environmental impact statement is released, BOEM will offer a comment period and hold public hearings

Stephens leaves Vineyard Wind

Barrington native and Providence resident Erich Stephens resigned at the end of 2019 from Vineyard Wind, a company he helped found in 2009 and is now co-owned by Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners. The original wind company was called Offshore MW. Prior to Vineyard Wind, Stephens was head of development for Bluewater Wind, one of the first U.S. offshore wind companies.

Stephens has considerable roots in Rhode Island. He attended Barrington High School and received his undergraduate degree from Brown University. He was founder and executive director of People’s Power & Light, now called the Green Energy Consumers Alliance. He was also a founding partner of Solar Wrights, a residential solar company that was based in Barrington and moved to Bristol. The company was later acquired by Alteris Renewables. Stephens also worked for two of Rhode Island’s first oyster farms.

More megawatts

New York plans to add 1,000 megawatts of offshore wind power to the 1,700 megawatts it awarded last summer to offshore wind projects that will deliver electricity to Long Island and New York City.

The state also announced it’s taking bids for $200 million in port development projects that will support the offshore wind industry.

The recent notifications are part of the state’s Green New Deal, which aims for 9 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2035 and 20 large solar arrays, battery-storage facilities, and onshore wind turbines in upstate New York. The state aims for 100 percent renewable energy by 2040.

The latest offshore wind projects consist of the 880-megawatt Sunrise Wind facility, developed by Ørsted and Eversource Energy, to power Manhattan. Long Island will receive up to 816 megawatts from the Empire Wind facility, developed by Equinor of Norway.

Pricing for the projects hasn’t been made public.

Offshore leader

Based in Denmark, Ørsted is the early leader in the size and number of U.S. offshore wind projects. Ørsted was awarded the 400-megawatt Revolution Wind project for Rhode Island. It’s also developing the 1,100-megawatt Ocean Wind facility in New Jersey, a demonstrations project in Virginia, and projects in Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Maryland. The company acquired Providence-based Deepwater Wind in 2018 for $510 million.

Ocean Wind, New Jersey’s first offshore wind project, and the 120-megawatt Skipjack Wind Farm off Maryland will use General Electric’s huge 12-megawatt Haliade-X turbines. The 853-foot-high turbines are the tallest in production and have twice the capacity of the 6-megawatt GE turbines now spinning off Block Island, which are 600 feet tall.

Tim Faulkner is a journalist with ecoRI News.

Taking them in

Here’s a brand-new watercolor by William Hall. There’s show of his watercolors at the Jessie Edwards Studio, on Water Street, Block Island, R.I., through Sept. 4.

The back story of the painting here is that Howard Milikin, a great-grandfather of Mr. Hall, was a navigational pilot from Block Island. He would be ferried from Block Island to meet incoming clipper ships and then pilot them into New England ports. His license was unlimited.

Those pesky island police logs

Downtown Block Island from the New London ferry.

Block Island Police Chief Vincent Carlone doesn’t want the island’s weekly newspaper, the Block Island Times, to publish police logs identifying people arrested for such offenses as drunken driving because, he says, it’s unfair to shame them in this way. Or is it because he thinks that publishing such logs would be bad for business on the resort island, which is almost entirely dependent on tourists (many of whom are not averse to getting drunk) and rich summer residents? (B.I. has turned into something of an extension of the Hamptons in recent years.)

In a Sept. 4 story, headlined “Chief lobbied paper not to run crime stories,’’ the chief told The Providence Journal:

“This is a nice community, and I’ve made that representation to them {a request that the paper not publish on paper or online police logs}.’’ And he said that the paper has “apparently agreed at some level.’’ Indeed, the paper has not published the arrest log for quite some time, although it had been a tradition for years.

Well, I think that people on such a small place as Block Island deserve to know what’s going on and to be able to decide for themselves what constitutes a serious offense. Drunk driving, for one, would seem to fall under that heading, since it can get people killed. John Pantalone, who’s chairman of the University of Rhode Island’s journalism program, told The Journal how he sees the problem:

“If the Police Department has chosen to withhold this information so as not to embarrass people in a small community, that seems like a bad policy. Communities need to know about misbehavior both for their own protection and to discourage further, perhaps more serious, misbehavior.”

The biggest problem in publishing such police logs is that sometimes a charge doesn't hold up and/or anarrest is found invalid. News media are morally obligated to inform the public when that happens but they often don’t, or they publish the update so inconspicuously that virtually no one sees it. Very unfair!

In any event, these logs are public records. It’s up to the Block Island Times what to do with them.

Of course, most people love to read the dirt on local bad behavior. Most of us have a voyeuristic streak and a touch ofschadenfreude – pleasure at seeing someone else’s misfortune. No matter how bad we think things are for us, someone near us has it worse. How comforting!

Not running police logs cuts readership. The Providence police reports once were among the most read things in The Providence Journal and the very droll “Crime and Punishment’’ section of The Boston Guardian (on whose board I sit) may be the most read part of that paper, Boston’s biggest weekly. (More exciting might be a story there about an apartment at 39 Beacon St. being rented for $50,000 a month – another sign of just how fancy downtown Boston has become because ofmoney from financial services, health services, tech and flight capital flowing in from around the world. If only Providence could siphon off more of that moolah. So near and yet so far.)

It’s unclear if the police logs policy has anything to do with the paper’s sale last year to Michael Schroeder, who owns several Connecticut newspapers, and has links with casino mogul (and Trump pal) Sheldon Adelson.

Hit this link to read the Block Island story:

http://www.providencejournal.com/news/20170903/block-island-police-chief-says-hes-lobbied-to-keep-crime-stories-out-of-print.

Nautical life on Block Island

From William T. Hall’s new exhibit of watercolors, “Block Island Nautical Life and Historical Views,” depicting earlier times of boating and fishing on Block Island. The show runs through Aug. 2 at the Jessie Edwards Studio, on Block Island.

In the show, the gallery says, you can see Mr. Hall’s "use of classical watercolor techniques, his knowledge of boats and Island history, and his talent for story telling {combining} to make this exhibit both a meticulous rendering of old working boats and a narrative of the quotidian concerns of Island mariners. We see the images, and we can read Hall’s brief accompanying stories that draw us into an earlier time on Block Island. ''

Maintenance by the moon

Watercolor by William Hall, part of his show at the Jessie Edwards Gallery on Block Island, scheduled for this July.

Mr. Hall explains that this picture is about scraping the bottom of boats, in this case a Block Island Double Ender, at very low tides Seaweed and barnacles slowed work boats. So this stuff needed to be regularly scraped off. Predictable very low tides would leave parts of Old Harbor, on Block Island, above water for 6 to 8 hours a day for several days in a row in the 19th Century heyday of these boats, which were essential for the islanders' fishing and transportation needs.

Double Enders were secured to the dock to wait for the extreme low tides. When they sat on the mud the work could be done. After scraping, antifouling paint was applied. Several fishermen and their wives worked together to get the scraping and painting done fast within the window of opportunity provided by the low tides.

"Think of it as fishermen's barn-raising. Over two days several boats could fully scrapped, '' Mr. Hall says.

Robert Whitcomb: Transportation and other news

Excerpted from the Sept. 9 Digital Diary column in GoLocalProv.

Terrific transportation improvements in Boston in the last 20 years because of the Big Dig and the creation of the South Station intermodal transportation complex have helped make Greater Boston richer. A key element has been the expansion and uniting of train and bus service at South Station. (Linking that facility with North Station via a direct MBTA train line would help expand the progress.)

Yes, these projects are expensive, but, as with the improvements in subway service in New York under Mayors Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg, the economic benefits of more efficient and pleasant transportation are impressive.

Thus kudos to the Rhode Island Department of Transportation for working to create a sort of mini-version of the South Station public-transportation center in and around Providence’s Amtrak/MBTA station. The few bad things that happened with the revival of much of downtown Providence starting in the ‘80s included moving the train station up the hill to across from the State House and what was then called the Bonanza Bus Terminal way north of downtown to a gritty, windswept, pedestrian-unfriendly area next to Route 95. Stupid moves for a city that wants to be walkable.

Well, the train station is stuck where it is but building a bus station complex right next to it would make public transportation a lot easier in Providence, which would boost its economy and quality of life. That a lot of younger adults avoid driving and the number of old people who can’t or won’t drive is rapidly increasing, mean that the numbers who want to use public transportation can only swell.

As part of all this, there should be very frequent nonstop RIPTA shuttle buses to and from the new intermodal center to Green Airport, barring a big expansion in MBTA train service there from the Providence train station.

The RIDOT’s project will help pullmore businesses and shoppers to Providence from a large swath of southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Connecticut.

Full speed ahead on this project.

xxx

In other transportation news: My wife and I were on Block Island for a (bravely scheduled) wedding on Labor Day weekend, though not for as long as we had hoped. While we were able to take in a big outdoor pre-wedding picnic on a spectacular heath from which you can often see Montauk Point, we had to leave hours before the wedding, scheduled for late Sunday afternoon, because the ferry folks told us that the last trip for the next few days would leave soon because of concerns about Post-Tropical Storm Hermine. As it turned out, the trip, while a bit bouncy at the start as we moved out of the harbor, was pleasant enough.

There were on board a few somewhat oafish morning beer drinkers – a tribe traditionally associated with Interstate Navigation Co.’s ferries, but fewer than I remember from our first trips on the service, way back in the late ‘70s. None threw up.

The trip reminded us of how dependent islanders are on the weather: However high tech they are they are, they must obey Mother Nature more than most people. While this can be inconvenient, it’s also edifying (teaching patience and respect for, and sometimes fear of, Mother Nature) and adds some drama to programmed lives.

September has the best weather of the year, except when it has the worst, during those rare but memorable visits from hurricanes. By the way, there’s something exciting about the sexy term “tropical storm’’ up here that gets people’s attention. Thus even though Hermine was a post-tropical storm as she dawdled south of New England in the first part of this week, the National Weather Service kept using the phrase “Tropical Storm Warning’’ for the New England coastal areas being affected.

That’s because after Hurricane Sandy, in 2012, became an extra-tropical storm some people ignored the warnings as she slammed into the Jersey Shore. So the NWS decided to keep the ominous if misleading word “tropical’’ this time around, though Hermine by any other name (such as “gale’’) would be as windy.

Offshore windpower: They'll come to love it

Excerpted from the Sept. 1 "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.

It’s too bad that it has taken so long, but the completion of Deepwater Wind’s five-turbine wind farm off Block Island, R.I., is very good news for New England.

The facility, expected to start producing electricity inNovember, will mean that a little more of New England’s electricity will come from the region’s own sources andthat we might be able to use a little less natural gas from fracking. That process, contrary to the corporate publicity and wishful thinking, does not slow global warming because the process releases so much methane from the fracking sites. And the Block Island project will help reduce air pollution: The island’s electricity has been produced by unavoidably dirty diesel fuel.

Further, success in getting this project up will boost, by example, much bigger offshore windpower projects planned for nearby waters, most notably between the eastern tip of Long Island and Martha’s Vineyard. Eventually, this should dramatically improve the reliability of our electricity and in the long run cut its cost as windpower technology improves.

As usual with such projects in places like Block Island, Deepwater Wind had to fend off some affluent summer people who were offended that they’d have to look at wind turbines (which many folks think are beautiful) on their horizon. Most famously, a group of very few rich people in Osterville, Mass., led by Bill Koch (of the Koch Brothers) have managed to block the big Cape Wind project, which was to go up in middle of Nantucket Sound, although the project has been supported by a large majority of theMassachusetts public. Yet again, a few privileged NIMBYs have sabotaged the public interest. (I co-wrote (with Wendy Williams) a bookabout that controversy, called Cape Wind, later made into a movie called Cape Spin.)

The Obama administration and some states, including Rhode Island and Massachusetts have, to their credit, enacted laws and regulations to encourage offshore wind. This is especially attractive in the Northeast, with its reliable breezes and shallow water extending a lot further offshore than you see off the West Coast.

The Europeans have long embraced offshore windpower, for environmental reasons and to reduce reliance on fossil-fuel imports, especially from an increasingly aggressive Russia.

I predict that many current offshore-windpower foes will come to tolerate and even like the turbines’ curious beauty. And the fishermen will come to love them because fish congregate in the supports of such structures.

-- Robert Whitcomb

Llewellyn King: Addressing the storage challenge in green energy

The energy-storage train discussed below (1/4 scale).

Editor’s note: With the windpower project off Block Island soon to go online, the issue of energy storage comes to mind.

In research there is evolution, revolution and — sometimes — what I call “retro revolution,” which happens when old methods have new applications. All three are in play in the world of electricity, and are affecting storage.

The inability to store electricity has been a challenge since the time of Thomas Edison. Electricity is made and used in real time, putting huge pressure on utilities at particular times of the day. For much of the East Coast in summer, for example, the peak is in the evening, when people come home from work or play, crank up the air conditioning, flip on the lights, the TV and start cooking. In many cities, the subways operate at peak and the electricity supply is stretched.

Traditionally, there have been two ways to deal with this. One is that utilities have some plant on standby, in what is called “spinning reserve,” or they have gas turbines ready to fire up.

Solar and wind power, an increasing source of new generation, have made the need to store and retrieve power quickly more critical. The sun sets too early and the wind blows willy-nilly. Also the quality of the power reaching the grid varies in seconds, necessitating a quick response to ease supply or increase it.

Until now, the best way to store large amounts of electricity — it is never really stored, but has to be generated afresh — is known as “pump storage.” This occurs when water is pumped up a hill during low demand times, at night and early in the morning, and released through generators to make new electricity during peaks.

It has gotten harder and harder to get permission to install new pumped storage because the best locations are often in scenic places. In 1962, Consolidated Edison Co. proposed building a pump storage facility on the Hudson River at Storm King Mountain near Cornwall, N.Y. After 17 years of environmental opposition, it gave up.

Now battery technology has reached a point where utilities are installing banks of lithium-ion batteries to help with peak demand. They also play an important part in smoothing out variable nature of alternative energy.

Batteries are not the only play, but because Mr. Battery, entrepreneur Elon Musk, is a showman, they tend to get more public attention.

Other mechanical methods hold as much promise and some dangers. One is flywheels, which would be wound up at night and would release power when needed. It is an old concept, but one that has new proponents — although there are concerns about when things go wrong and that super-energetic device flies apart.

“What happens if it gets loose and goes to town?” asks a wag.

Another method is compressed air in underground vaults. Natural gas already is compressed routinely for storage. The technology exists, but the compression would have to be many times greater for air, and there are concerns about the impact of this “air bomb.”

Yet another method involves a column of water with a heavy, concrete weight pressing down on it.

My own favorite — and one likely to appeal to many because of its safety and mechanical efficiency — is an electric train that stores energy by running up a track and then down to generate power. A Santa Barbara, Calif., company, Advanced Rail Energy Storage (ARES), is planning to run a special train 3,000 feet up a mountain track in Pahrump, Nev., and then have the train come down the mountain, making electricity as it does so. They plan to use hopper cars loaded with rock or other heavy objects. The Economist magazine has dubbed it the “Sisyphus Railroad.”

The train will go up or down the track depending on the needs of the California grid to which it will be linked. The developers claim an incredible 85-percent efficiency, according to Francesca Cava, an ARES spokeswoman. “That’s what you get with steel wheels on steel track,” she says.

The company has received Bureau of Land Management approval for its 5.5-mile track, and construction of the energy train starts next year. “All aboard the Voltage Express making stops at Solar Junction, Wind Crossing and Heavy Goods Terminal.”

Choo-choo! Back to the future.

Llewellyn King (llewellynking1@gmail.com), based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a longtime publisher, columnist and international business consultant. The piece first ran on InsideSources.

Wind wins on Block Island

With surprisingly little fanfare, except in the glorious Block Island Times, what would be the first offshore wind farm in America has received its final major regulatory approval, from the Army Corps of Engineers. It's on schedule to be up and running in two years. The Block Island Wind Farm -- Deepwater Wind's five-turbine , 30-megawatt operation -- would lower Block Island's sky-high electricity costs and would act as an encouragement for backers of other, much bigger projects, such as the Cape Wind project, in Nantucket Sound. That project has been held up for years by Osterville, Mass., summer resident and fossil-fuel mogul Bill Koch.

How difficult it has become to do big projects in America, especially when a few local rich people don't like them!

'Lame Deer' and 'culled' ones

"Lame Deer (Big Eagle)'' (oil on French linen), by ROBERT S. NEUMAN, in the "Robert S. Neuman: Lame Deer Series,'' at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., Feb. 23-May 18.

Soon there will be many fewer deer on Block Island, as a Connecticut firm is being brought in to "cull'' the herd, whose population, and that of the deer ticks that carry Lyme disease, have swollen. Brutal world.