Llewellyn King: A great process movie about the press; an apology at a famed restaurant

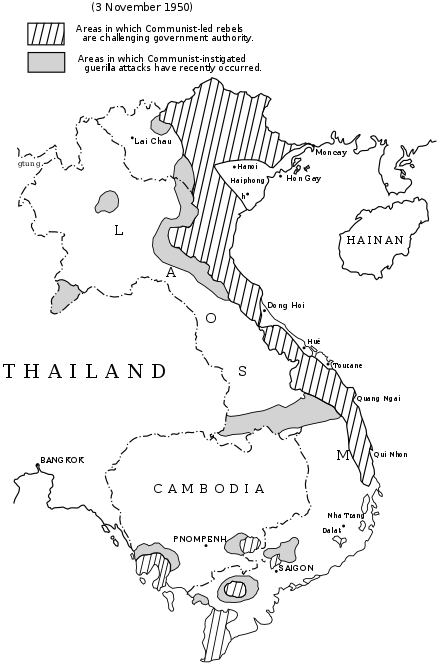

A CIA map of dissident activities in Indochina, published as part of "The Pentagon Papers.''

I read somewhere that director Steven Spielberg says he does not read books. However Spielberg gets his information, he has gotten the newspaper trade right, very right in The Post.

It is one of the best films about the inside workings of a newspaper.

It involves the decision, reached between the publisher of The Washington Post and its editor in June 1971, to publish the collection of secret documents detailing the hopelessness of the Vietnam War from 1964 onwards. Collectively, these are known as "The Pentagon Papers''. They showed conclusively that the government had always known that the war was a losing proposition and covered it up. They also, it must be said, showed that the media, for all the reporters crawling over South Vietnam, did not know what the government knew. The story was missed.

This is a film apposite for our time, both as an illustration of the duplicity of governments, in this case under Democratic and Republican administrations (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon), and the key role of a free press in checking government.

It is also a shot in the arm for the newspaper trade, which is under attack frontally from President Trump and his merry band of besmirches and from financial undermining, occasioned by the flight of advertisers to the Internet.

This is a work that is not only fine entertainment but also very accurate. I can make that statement because I was working at The Washington Post at the time and I knew the protagonists, Ben Bradlee, the storied editor, and his publisher, Katharine Graham.

Watching this film I marveled at how much Tom Hanks looked like Bradlee, given he was a little heavier than Bradlee, who delighted in looking like David Niven playing a jewel thief in the South of France. Graham, always called “Mrs. Graham,” is very well replicated by Meryl Streep, although Graham was a little taller and maybe a smidgeon more imperial.

It is Hanks's portrayal of Bradlee that floored me. He is Bradlee, the boulevardier who used profanity as a tool and could drop an expletive as though it were a precision-guided munition.

Graham and Bradlee risked prison to publish the papers, as did editor Abe Rosenthal and publisher Arthur Sulzberger, at The New York Times. You will come out of this movie feeling good about the First Amendment, good about newspapers, bad about governments.

You will be very glad the film industry has a talent as great as Spielberg.

A lesser director might have settled for getting Graham and Bradlee right, but Rosenthal and Ben Bagdikian, The Post's national editor, too? That is meticulous.

Even the atmosphere of the composing room, back when linotype machines clattered and skilled fingers spaced and secured the little lines of type, is authentic. Hot-type aficionados, like me, rejoice.

Those were the days. And this is the movie.

The Night That Paul Bocuse Messed Up

Paul Bocuse, widely described as the most important chef of the last century, has died at 91. He invented "nouvelle cuisine,'' a new form of high French cooking. More fresh produce, lighter sauces and the imaginative pairing of flavors and ingredients marked it. It is reflected in nearly all the fashionable restaurants of today and has influenced chefs around the world.

I was lucky enough to be a guest, along with 11 other diners, at the great man’s legendary restaurant L’Augberge du Pont de Collonges, near Lyon. It was an experience that foodies dream about. The restaurant had an open kitchen of the kind that came to be associated with California: You could watch the chefs work. Bocuse and his wife both stopped by our table.

The food? Exceptional – even though one order got lost. The order just didn’t make it out of the kitchen, and the result was the whole restaurant felt the shame.

When we left one of the captains followed me -- thinking that I might be a food writer, which I was not -- to apologize. He said simply, “Please believe me, we usually do better.”

Indeed, the great chef did, and in doing so changed the world of fine dining.

When I have told this story to people who know more about Bocuse and his legacy than I do, they tell me I may be the only person who left with an apology: a three-star Michelin apology. I am humbled.

The Things They Say

"Facts are better than dreams.''

-- Winston Churchill

Llewellyn King, executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, is a veteran publisher, editor, columnist and international business consultant. He's based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Bradlee's cult of personality

Over the years I ran into Ben Bradlee a few times, mostly when I was the finance editor of the International Herald Tribune -- The Washington Post then owned a third of its stock -- and even had dinner with him once in Paris, with Donald Graham (of The Post's owning family) and a secretary. He couldn't have been more charming or friendly.

While full of bonhomie, Bradlee evoked a powerful sense of privilege that I sometimes found a bit off-putting. But then, he grew up in a Boston Brahmin family, albeit one that had somewhat straitened circumstances (compared to its earlier condition) because of the Great Crash of 1929. (Still, there were enough rich relatives around to send him to fancy schools.)

Because of the immense confidence with which he carried himself, his theatricality, his studly good looks, his memorable mix of the patrician and a swearing sailor, and his social connections with the owners of The Post and other grandees, his Post editorship developed into a cult of personality, which I think he much enjoyed cultivating.

It got rather silly: Many of the other senior editors and reporters started to wear his brand of expensive shirts from London, use many of his salty and other expressions and laugh at even his bad jokes. I witnessed this suck-up in full flower in a couple of news meetings at The Post in which he presided.

He had a tendency to studiously ignore (and even try to make leave the paper) those who had fallen out of his favor, such as by boring him. This created an atmosphere of fear in the newsroom that competed with the pride and energy that the rise of the paper and his charisma fueled. A friend of mine there, an editor, used to joke that he sat at his desk everyday "watching the blood drip down the walls.'')

Whatever, he was a great editor, especially for someone who did remarkably little hand's-on editing, which would have required missing too many Georgetown dinner parties. He made the right choices for the paper and the nation in printing the Pentagon Papers and pushing the Watergate stories. However, I'm not sure how much social courage was involved in those decisions; most of his social group hated Nixon. It's possible, however, that printing the Pentagon Papers could have landed him in jail for contempt of court. I suspect he would have reveled in that publicity.

In any event, Bradlee picked the perfect stretch of time to work in the newspaper business.

Llewellyn King: The Bradlee I knew and the creation of 'Style'

Ben Bradlee, who died Oct. 21 at 93, did not so much edit The Washington Post as lead it.

Where other editors of the times would rewrite headlines, cajole reporters and senior editors, and try to put their imprint on everything that they could in the newspaper, that was not Bradlee’s way. His way was to hire the best and leave them to it.

Bradlee often left the building before the first edition “came up,” but it was still his Washington Post: a big, successful, hugely influential newspaper with the imprimatur of one man.

Bradlee looked, as some wag said, like an international jewel thief; someone you would expect to see in one of those movies set in the South of France that showed off the beauty of the Mediterranean and beauties in bikinis while the hero planned a great jewel heist.

I worked for Bradlee for four years and we all, to some degree, venerated our leader. He had real charisma; we not only wanted to please him, but also we wanted to be liked by him.

Bradlee was accessible without losing authority; he was all over the newsroom, calling people by their first names and sometimes by their nicknames, without surrendering any of the power of his office. He was an editor who worked more like a movie director rather than the traditionally detached editors I had known in New York and London.

The irritation at the paper -- and there always is some -- was not so much that Bradlee was a different kind of editor, but that he had a habit, in his endless search for talent, of hiring new people and forgetting, or not knowing, the amazing talent already on the payroll. The Post was a magnate for gifted journalists, but once hired, there were only so many plum jobs for them to do. People who expected great things of their time at the paper were frustrated when relegated to a suburban bureau, or obliged to write obituaries for obscure people.

Yet we knew we were putting out a very good paper and, in some ways, the best paper in the United States. This lead to a faux rivalry with The New York Times. Unlike today, very few copies of The Times were sold in Washington, and even fewer Washington Posts were sold in New York.

Much has been made of Bradlee’s fortitude, along with that of the publisher, Katherine Graham, in standing strong throughout the Watergate investigation that led to President Nixon's registration. But there was another monumental achievement in the swashbuckling Bradlee years: the creation of the Style section of the newspaper.

When Style first appeared, sweeping away the old women’s pages, it went off like a bomb in Washington. It was vibrant, rude and brought a kind of writing, most notably by Nicholas von Hoffman, which had never been seen in a major newspaper: pungent, acerbic, and choking on invective. Soon it was imitated in every paper in America.

The man who created Style was David Laventhol, who came down from New York to fashion something new in journalism. Laventhol was a newspaper mechanic without equal, but Bradlee was the genius who hired him.

When I worked at The Post, I interacted a lot with Bradlee; partly because we enjoyed it, and partly because it was the nature of the work. I knew a lot about newspaper production in the days of hot type and he affected not to. That gave Bradlee the opportunity to exercise one of his most winning traits: disarming candor. “I don’t know what’s going on here,” he said one frantic election night in the composing room.

But when it came to big decisions, Bradlee knew his own mind to the exclusion of the rest of the staff. The nerve center of a newspaper is its editorial conferences -- usually, there are two every day. The first conference is to plan the paper; the second is a reality check on what is new, and how the day is shaping up.

At these conferences, Bradlee would listen from behind his desk. But when he disagreed with the nine assistant managing editors, and others who needed to be there, he would put his feet on the desk, utter an expletive and cut through fuzzy conversation like a scimitar into soft tissue. As we might say nowadays, he had street smarts. They were invaluable to his editorship and to his charm.

Llewellyn King (lking@kingpublishing.com) is executive producer and host of “White House Chronicle” on PBS. He is a longtime publisher, broadcaster, writer and international business consultant.